Abstract

Background

Emergency hand service is a national problem both for civilian and veteran patients. The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health system began coordinating emergency hand coverage within the plastic surgery service in 2008. Consult templates were designed to facilitate access to the appropriate service. Trainees were taken out of transfer decisions. Clinic templates were designed to fast track urgent patients to 8 a.m. appointments. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of our templates and triage system.

Methods

All consults completed by the plastic surgery service were reviewed retrospectively. Emergent and urgent hand consults were identified. Time from consult submission to the patient being seen by the plastic surgery provider was recorded. Time frames were categorized as same day, next day, within 2 days, less than or equal to 7 days, and greater than 7 days. Type of emergency (trauma or infection) and treatment plan were noted.

Results

There were 1,090 consults in 2007 and 1,868 consults in 2012 that were completed by the plastic surgery service. We found the number of urgent and emergent hand consults increased by a factor of 6 (49 to 294). Furthermore, 16.3 % (8/49) of patients were seen greater than 1 week after consult submission in 2007, compared with 8.1 % (24/294) of patients in 2012. Only one patient from 2007 and two patients from 2012 went to the OR after regular operating room hours.

Conclusion

A well-coordinated effort to speed access for hand emergencies can minimize expenses and improve quality of care

Keywords: Hand trauma, Triage, Template, Hand emergency

Background

Emergency hand service is a national problem both for civilian and veteran patients. The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health system began coordinating emergency hand coverage within the plastic surgery service in 2008. Hand emergencies were previously treated by various surgical and nonsurgical services and occasionally fee-based outside the VA.

Consult templates were designed to facilitate access to the treating service. The patients were either seen right away or instructions were given to the referring provider, which were transferred to the template to be available when the consult request was reviewed by the plastic surgery staff. All phone calls from outside the immediate facility were directed to the plastic surgery faculty on call to provide follow-up instructions and avoid unnecessary transfers. Clinic profiles were set up with urgent 8 a.m. appointments to capture the ER and urgent care follow ups that may need to be fast-tracked through preanesthesia clinic, treated in clinic, or expedited to hand therapy.

Fellows, interns, secretaries, clerks, ER staff, phone operators, and primary care physicians were educated on the triage system. The objective of the triage system was to improve the speed of diagnosis and treatment of hand emergencies. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of our templates and triage system.

Materials and methods

An IRB approved (2013–00057) retrospective study was performed on all consults completed by the Malcom Randall VA plastic surgery service for the years 2007 and 2012. All urgent and emergent hand consult requests were identified. The date of consult placement and the date when a physician from the plastic surgery service saw the patient were noted. Time frames were logged as same day, next day, 2 days, less than or equal to 7 days, and greater than 7 days. The type of pathology (trauma vs. infection) was recorded. The treatment plan (surgery, office procedure, splint, or antibiotics) was recorded.

Results

A total of 1,090 consults were completed in 2007 by the plastic surgery service. Thirty-three consults were for hand trauma and 16 were for hand infections. A total of 1,868 consults were completed in 2012 by the plastic surgery service. Two hundred thirty-eight of these were for hand traumas and 56 were for infections. The number of urgent or emergent hand consults went up by a factor of 6 (49 to 294) once the plastic surgery service took over emergency hand call. Eight patients (16 % of the total) were seen after 7 days in 2007 (Table 1). Twenty-four patients (8.1 % of the total) were seen after 7 days in 2012 using the new triage system (Table 2). When we reviewed the charts of the patients seen after 7 days in 2012, 10 of the 24 were given earlier appointments, but chose a later date, which reduced the percent of patients scheduled later than 1 week after consult placement to 4.7 %. One patient was taken to the operating room after 6 pm in 2007 for an infection. Two patients were taken to the operating room after regular operating room hours in 2012, both for infections.

Table 1.

Hand trauma triage 2007: speed of access

| 1090 Consults completed | Same day | Next day | 2 days | < or = 7 days | >7 days | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma | 13 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 33 |

| Infection | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 23 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 8 (16 %) | 49 |

Table 2.

Hand trauma triage 2012: speed of access

| 1868 Consults completed | Same day | Next day | 2 days | < or = 7 days | >7 days | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma | 59 | 39 | 33 | 85 | 22 | 238 |

| Infection | 36 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 56 |

| TOTAL | 95 | 46 | 37 | 92 | 24 (8.1 %) | 294 |

Discussion

Greater than 10 % of emergency room visits due to injuries are localized to the hand, wrist, and finger [5, 6]. There is a known lack of emergency hand services in the US [8]. Counties that are medically underserved and with low income tend to have difficulty finding emergency hand coverage [1]. Surgical specialists have been steadily dropping their hand call privileges due to financial pressures, medico-legal risk, specialty competence, and time requirements [4]. This results in costly patient transfers and delays in care. There has been discussion and recommendations made for regionalization of hand care to better coordinate treatment [2]. A treatment protocol coordinated between the ER physicians and local hand surgeons has been demonstrated to improve care and efficiency in a South West Florida community where a hand referral consult service is available by phone 24/7/365 [4].

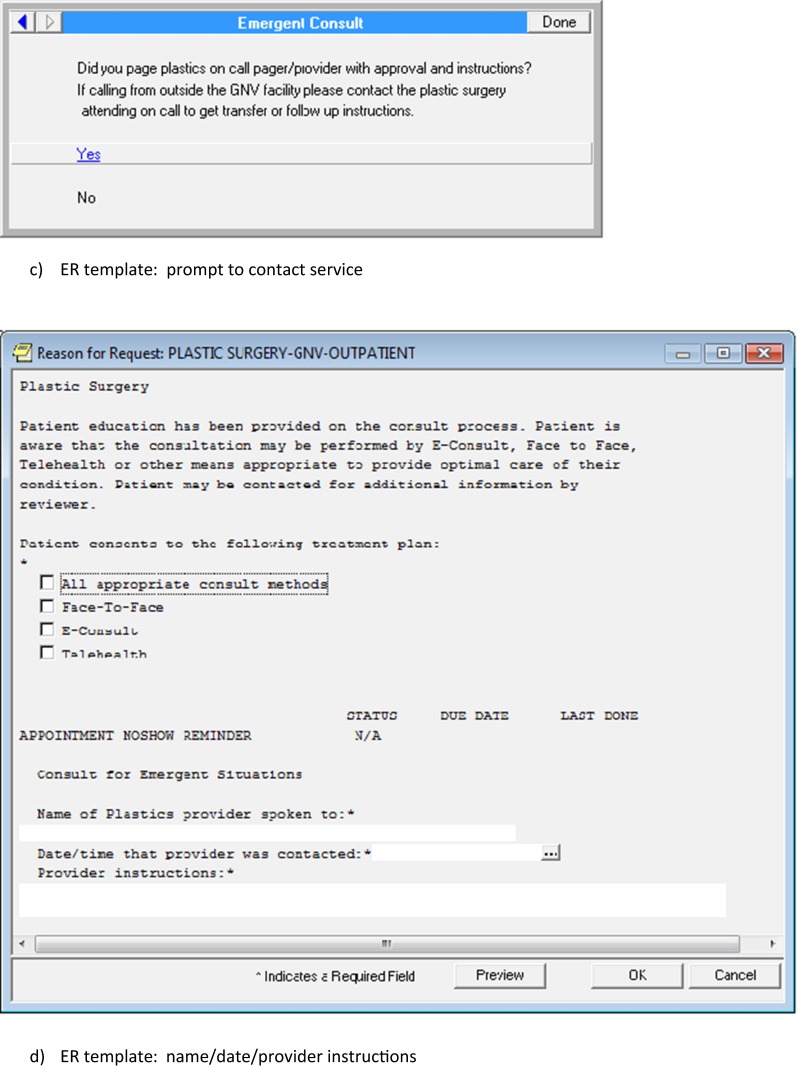

The North Florida/South Georgia healthcare catchment area is approximately the size of South Carolina and serves greater than 393,000 veterans (communication with the Director’s office, Malcom Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville, FL 2/10/2014). The urgent care, primary care, and ERs receive a variety of hand cases ranging from closed fractures (Fig. 1a, c) to devascularizing injury (Fig. 1b) and compartment syndrome (Fig. 1d) to tendon injuries (Fig. 1e) and necrotizing infection (Fig. 1f). The plastic surgery service has been coordinating and treating these emergent cases since 2008. The triage template (Fig. 2a–d) requires the referring provider to directly contact the plastic surgery service to present the case and get instructions. Patients may be seen the same day by the service or directed to an early morning 8 a.m. clinic appointment, all of which are reserved for ER and urgent care follow ups. All calls from outside providers go directly to the plastic surgery faculty. These measures help prevent unnecessary and costly transfers between facilities.

Fig. 1.

Hand emergencies: a jersey finger, b devascularizing/avulsion injury, c metacarpal fracture, d compartment syndrome, e zone 2 flexor tendon injury, and f necrotizing infection

Fig. 2.

ER hand emergency/trauma template: a ER template: region of body, b ER template: tentative diagnosis, c ER template: prompt to contact service, and d ER template: name/date/provider instructions

Studies have demonstrated that lack of emergent hand coverage has led to misuse of emergency resources. Uninsured patients have been found to make repeated emergency room visits in search of hand and wrist care referrals [7]. Inappropriate transfers of uninsured or underinsured patients to one level 1 trauma center in Virginia over a 22-month period was found to cost $124,151 in physician charges, facility fees, and transportation [3].

This triage system works well within a healthcare system with an electronic medical record where the referring and receiving physicians can read the same notes and labs and visualize the same pictures and films from hundreds of miles away. The information provided on the consult templates prevents confusion when a patient contacts the clinic looking for follow up because the staff can identify what the plan is for that patient and who developed the plan. This may not work as well for a level 1 trauma center where referring and receiving clinicians do not have access to the same information. A level 1 can also expect a higher volume of emergency cases; however, a coordinated infrastructure can potentially minimize some of the after-hours cases staffed by a less experienced hand team by rapidly getting the patient through the correct follow-up channels.

The ER physicians within our system understand that they always have surgical back up for hand cases they feel comfortable treating in the ER setting. We have found that this encourages early emergency room treatment such as wound washout, I + D’s, simple closures, and splinting without the need for an emergent transfer or waiting for the arrival of an on-call physician. Prior to this effort, there was no consistent coverage of the emergent hand patients, who would often get bounced among services. One service taking charge of the emergencies saves the ER physician valuable time and avoids the “who’s on first?” discussion.

The consistency and coordination within our system has allowed us to downgrade many “emergent” cases into “urgent” cases, which avoids overutilization of valuable operating room time and allows us to place those cases on the elective schedule when resources are most accessible. Although our facility is not a level 1 trauma center, it has the skilled staff, ICU, and OR resources to treat devascularizing and necrotizing hand injuries when they have presented. The efficiency of one service covering a specialty that was previously difficult for the emergency care providers to locate may be potentially applied to other specialties, such as facial trauma, that also tends to have broad variations in coverage.

Acknowledgment

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville, FL.

Conflict of Interest

Loretta Coady-Fariborzian declared that she has no conflict of interest.

Amy McGreane declared that she has no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent

No patient-identifiable information was disclosed in this study.

Contributor Information

Loretta Coady-Fariborzian, Phone: 352-665-5285, Email: lmcoady@aol.com.

Amy McGreane, Email: Irishgator511@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Anthony JR, Poole VN, Sexton KW, et al. Tennessee emergency hand care distributions and disparities: emergent hand care disparities. Hand. 2013;82:172–8. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9503-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caffee H, Rudnick C. Access to hand surgery emergency care. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58(2):207–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000237636.37714.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friebe I, Isaacs J, Mallu S, et al. Evaluation of appropriateness of patient transfers for hand and microsurgery to a level 1 trauma center. Hand. 2013;8(4):417–21. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labs JD. Standard of care for hand trauma: where should we be going? Hand. 2008;3(3):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lifchez S. Hand education for emergency medicine residents: results of a pilot program. J Hand Surg. 2012;37(6):1245–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller MA, Zaydfudim V, Sexton KW, Shack RB, Thayer WP. Lack of emergency hand surgery: discrepancy between elective and emergency hand care. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68(5):513–7. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31823b6a35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potini VC, Bratchenko W, Jacob G, et al. Repeat emergency room visits for hand and wrist injuries. J Hand Surg [Am] 2014;39(4):752–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao MB, Lerro C, Gross CP. The shortage of on-call surgical specialist coverage: a national survey of emergency department directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(12):1374–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]