Inactivated influenza vaccines are manufactured using two methods. We compared the vaccine effectiveness (VE) of these vaccines in adults ≥50 years. VE was 77.8% (95% CI: 58.5, 90.3) and 44.3% (95% CI: −11.8, 70.9) for split-virion and subunit vaccines, respectively (VE difference = 33.5% [95% CI: 6.9, 86.7]).

Keywords: influenza, split-virion vaccine, subunit vaccine, clinical effectiveness, older adults

Abstract

Background. Inactivated influenza vaccines are manufactured using either split-virion or subunit methods. These 2 methods produce similar hemagglutinin antibody responses, but different cellular immune responses.

Methods. We compared the effectiveness of split-virion influenza vaccines to that of subunit influenza vaccines using prospectively collected data from adults aged ≥50 years who sought care for acute respiratory illness during 3 influenza seasons: 2008–2009, 2010–2011, and 2011–2012 using a case-positive, control test–negative study design.

Results. Complete data were available for 539 participants, of whom 68 (12.6%) had influenza detected. Influenza-infected patients were younger (P < .001), were more likely to have received no vaccine or the subunit influenza vaccine than the split-virion vaccine (P < .001), and more likely to have sought care in either the emergency department or the acute care clinic than the hospital (P = .001). Split-virion vaccine effectiveness was 77.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 58.5%–90.3%) compared with subunit vaccine effectiveness of 44.2% (95% CI, −11.8% to 70.9%), giving a difference in vaccine effectiveness of 33.5% (95% CI, 6.9%–86.7%).

Conclusions. Studies need to be done to further explore if there are differences in clinical effectiveness in older adults for the 2 vaccine manufacturing methods.

Until recently, the manufacture of all influenza vaccines started with a similar process, which still accounts for the majority of available vaccines. Influenza viruses are grown in pathogen-free eggs, and the virus membrane is disrupted with the use of a surfactant. Subunit vaccines are further purified using differing sedimentation to remove the internal subviral core [1]. Split-virion vaccines do not undergo further purification so they usually contain more protein, and because of this, are generally more reactogenic, which was a rationale for development of subunit vaccines [2]. Because split-virion and subunit vaccines contain similar amounts of hemagglutinin, they produce similar responses when tested by hemagglutination inhibition assay, the correlate of protection used for licensure, and are assumed to have comparable effectiveness [2]. However, this correlate of protection is imperfect [3, 4], and it is unknown if these vaccines have similar clinical effectiveness.

Cellular immune responses may be important in addition to antibody responses in older adults [3], as cellular immune responses have been associated with clearing influenza infection [5]. These cellular immune responses are directed toward internal proteins such as nucleoprotein, polymerases, and matrix proteins [5]. Due to manufacturing methods, split-virion vaccines contain more internal proteins, which may be important for cellular immune responses [6]. Co et al reported that split-virion influenza vaccines stimulated a stronger cellular immune response to influenza than subunit vaccines [6]. It is unknown whether differences in cellular immune responses translate into differences in clinical effectiveness. Using data collected to determine influenza vaccine effectiveness in older adults over several influenza seasons [7, 8], we performed a substudy to evaluate whether split-virion vaccines provided greater effectiveness than subunit vaccines for the prevention of medically attended acute respiratory illness associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

METHODS

Adults aged ≥50 years seeking medical care for acute respiratory illness or fever without other known nonrespiratory causes in 1 of 4 surveillance hospitals, an emergency department, or an acute care clinic from November to April during the 2008–2009, 2010–2011, and 2011–2012 influenza seasons in Nashville, Tennessee, were eligible [7, 8]. The 2009–2010 influenza season was excluded because the pandemic vaccine was not available until after peak circulation of the pandemic virus. A trained research assistant used a standard form to collect data on symptoms, smoking history, history of influenza vaccination, and use of certain medications (including steroids and home oxygen use). One nasal swab and 1 throat swab were collected for influenza testing using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention primers and probes [7, 8]. Chart abstraction included demographic data, past medical history, results of microbiologic tests, hospital course (if hospitalized), outcome of illness at discharge, and verification of influenza vaccination status. In addition, study staff verified vaccinations from traditional and nontraditional providers such as retail stores, employers, military, and public health officials.

Definitions and Covariates

A person was considered vaccinated if influenza vaccination was verified to occur at least 2 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms. Study nurses reviewed medical records for all patients regardless of self-report, to verify vaccination status, determine the duration between vaccination and illness, and obtain the vaccine manufacturer and lot numbers. If a participant denied vaccination, we confirmed with the primary care provider or nursing facility that no vaccine was given.

Influenza-positive cases were defined as participants with positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) results on duplicate testing. For patients with >1 enrollment, only the first influenza-positive enrollment or the first enrollment, if none were influenza positive, was included. Influenza-negative controls were defined as participants with respiratory illness who tested negative for influenza by RT-PCR testing and had evidence of β-actin or RNase P in the sample. Patients with indeterminate laboratory results, unknown vaccination status, or unknown vaccine manufacturer were excluded from the analyses.

Influenza seasons were defined by the total number of weeks that included all influenza-positive specimens from enrolled patients each year. Covariates obtained by self-report or medical records review included age in years, sex, race (black, nonblack), current smoking (in the past 6 months), home oxygen use, underlying medical conditions (diabetes mellitus, chronic heart or kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asplenia (functional or anatomic), immunosuppression (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], corticosteroid use, or cancer), timing of admission relative to the onset of influenza season, the specific influenza season, and site of enrollment (hospital, emergency department, or outpatient clinic). All covariates were considered as potential confounding factors.

Split-virion vaccines included Afluria, Fluarix, FluLaval, and Fluzone Standard Dose; subunit vaccines included Agriflu and Fluvirin. Fluzone High Dose vaccine recipients were excluded.

Analysis

Characteristics of patients who received split-virion vs subunit influenza vaccines and influenza-positive patients and influenza-negative controls were compared with the use of Pearson χ2 test for categorical covariates and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. The group without influenza immunization was used as the reference for both the split-virion and the subunit vaccines. Using the case-positive, control test–negative design, vaccine effectiveness estimates were calculated using the following formula: [1 – adjusted odds ratio (OR)] × 100% [9]. Adjusted ORs overall and for 3 age groups (50–64, ≥65, and ≥70 years), 3 influenza seasons, and 3 influenza strains (influenza A H1N1 and H3N2 and influenza B) were calculated. Covariates include age in years, sex, race (black, nonblack), current smoking (in the past 6 months), underlying medical conditions, immunosuppression (HIV, corticosteroid use, or cancer), the specific influenza season, timing of admission relative to the onset of influenza season, and enrollment site (emergency department, inpatient, outpatient). Underlying medical conditions included diabetes mellitus, chronic heart or kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asplenia (functional or anatomic). Restricted cubic spline function was applied to age and week of influenza season variables with 3 knots for each variable. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated by comparing split-virion vaccine compared with no vaccine and subunit vaccine compared with no vaccine between influenza-positive cases and influenza-negative controls using the logistic regression model with 3-level exposure variable (split-virion vaccine, subunit vaccine, and no vaccine) and lasso penalty on all potential confounders [10]. Lasso-type methods have been developed recently for high-dimensional data analysis when the number of parameters to be included in the model is large relative to the number of cases available. The penalty functions are chosen so that the model can yield zero estimates when the parameter values are close to zero and hence can perform the variable selection procedure. The difference in vaccine effectiveness was determined as the difference between the vaccine effectiveness for split and subunit. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed using 2000 bootstraps.

For the participants with influenza vaccine but unknown vaccine manufacturer, the reason was mostly due to missing vaccine lot number in their medical record, which is likely missing at random [11]. A sensitivity analysis was conducted including patients with missing vaccine type or any missing covariates after performing 20 multiple imputations [11]. All analyses were performed using R3.0.2 (r-project.org).

RESULTS

We enrolled 840 subjects during the 3 influenza seasons. Vaccination status was known for 775 subjects, of whom 539 had complete data and were either unimmunized or immunized with a vaccine of study interest. Of those excluded, 202 reported influenza vaccination but the vaccine manufacturer was unknown, 16 received high-dose vaccine, and 18 had missing data. Site of enrollment was the hospital for 427, emergency department for 20, and an acute care clinic for 92.

Of the 539 participants, 68 (12.6%) had influenza detected. Influenza-positive patients were younger (P < .001), were more likely to have received no vaccine or the subunit influenza vaccine than the split-virion vaccine (P < .001), and more likely to have sought care in either the emergency department or the acute care clinic than the hospital (P = .001) (Table 1). Approximately 40% of vaccinations were given outside a provider's office or clinic. We were able to verify approximately 78% (454/582) of all vaccinations. For vaccinations not given at a regular provider's office or clinic, 75% were verified.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants by Influenza and Vaccine Status

| Characteristic | Influenza Negative (n = 471) | Influenza Positive (n = 68) | P Value | No Vaccine (n = 185) | Split-Virion Vaccine (n = 204) | Subunit Vaccine (n = 150) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||||

| White | 80% (377) | 68% (46) | 71% (131) | 83% (169) | 82% (123) | ||

| Black | 18% (87) | 29% (20) | 26% (49) | 16% (32) | 17% (26) | ||

| Other | 1% (7) | 3% (2) | .06 | 3% (5) | 1% (3) | 1% (1) | .7 |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 65.9 (57.7–76.5) | 61.3 (55.1–67.5) | <.001 | 61.1 (55.1–69.7) | 67.5 (58.8–77.3) | 69.4 (60.1–76.9) | .3 |

| Sex, female | 60% (283) | 68% (46) | .2 | 66% (118) | 62% (127) | 56% (84) | .2 |

| High-risk medical conditions, Yes/No | |||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 46% (217) | 43% (29) | .6 | 44% (82) | 46% (93) | 47% (71) | .7 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 44% (205) | 34% (23) | .1 | 34% (63) | 45% (92) | 49% (73) | .5 |

| Immunosuppression | 35% (163) | 24% (16) | .07 | 28% (52) | 37% (76) | 34% (51) | .5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33% (157) | 25% (17) | .2 | 24% (45) | 38% (78) | 34% (51) | .4 |

| Kidney or liver disease | 13% (62) | 12% (8) | .7 | 9% (16) | 16% (34) | 13% (20) | .4 |

| Asplenia | 1% (3) | 1% (1) | .4 | 1% (2) | 1% (1) | 1% (1) | .8 |

| Current smoking | 21% (100) | 25% (17) | .5 | 30% (56) | 15% (30) | 21% (31) | .1 |

| Influenza positive | … | … | … | 21% (39) | 5.4% (11) | 12% (18) | .025 |

| Vaccine type | <.001 | ||||||

| Split-virion | 41% (193) | 16% (11) | … | … | … | … | |

| Subunit | 28% (132) | 26% (18) | … | … | … | ||

| No vaccine | 31% (146) | 57% (39) | … | … | … | ||

| Medical care setting | <.001 | .033 | |||||

| Outpatient acute care clinic | 16% (73) | 28% (19) | 17% (31) | 13% (26) | 23% (35) | ||

| Emergency department | 3% (14) | 9% (6) | 5% (10) | 3% (6) | 3% (4) | ||

| Hospitalization | 82% (384) | 63% (43) | 78% (144) | 84% (172) | 74% (111) | ||

| ICU admission | 11% (41) | 5% (2) | .2 | 12% (18) | 9% (16) | 9% (16 | .7 |

| Death | 1% (3) | 0% (0) | .5 | 1% (1) | 2% (2) | 0% (0) | .3 |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | .08 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | .2 |

| Discharge diagnoses | .1 | .8 | |||||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 37% (174) | 34% (23) | 37% (69) | 36% (73) | 37% (55) | ||

| Other acute respiratory illness | 16% (77) | 18% (12) | 17% (31) | 17% (35) | 15% (23) | ||

| Asthma or COPD exacerbation | 22% (102) | 21% (14) | 22% (40) | 20% (41) | 23% (35) | ||

| Cardiac disease | 9% (41) | 2% (1) | 8% (14) | 9% (19) | 6% (9) | ||

Data are presented as % (No.) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

aP value is for subunit vs split-virion vaccine.

One hundred fifty participants received a subunit vaccine, and 204 received a split-virion vaccine (Table 1). Patients who received split-virion vaccines were similar to patients who received subunit vaccines except that fewer split-virion recipients developed influenza (5.4% vs 12%; P = .025). Patients who did not receive an influenza vaccine were more likely to be black (P = .006), to smoke (P < .001), to have influenza (P < .001), and to be younger (P < .001), and less likely to have cardiovascular disease (P = .005), diabetes (P = .004), and/or kidney or liver disease (P = .03) compared with those who were immunized.

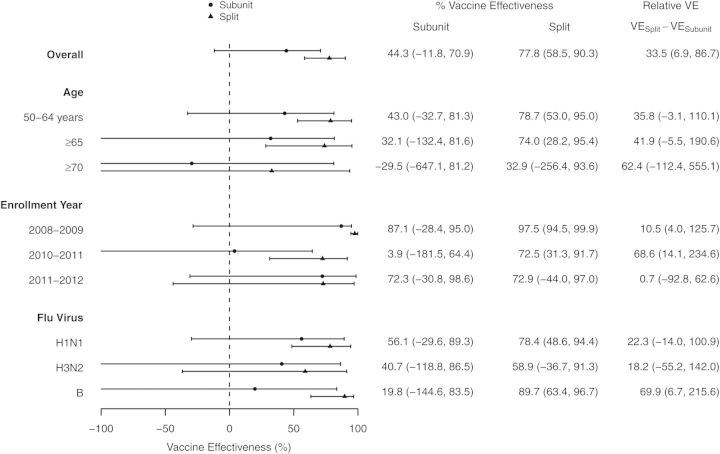

The adjusted vaccine effectiveness for the split-virion vaccine for the prevention of medically attended respiratory illness due to laboratory-confirmed influenza in adults ≥50 years of age was 77.8% (95% CI, 58.5%–90.3%), whereas that of the subunit vaccine was 44.2% (95% CI, −11.8% to 70.9%), giving a vaccine effectiveness difference of 33.5% (95% CI, 6.9%–86.7%). Figure 1 shows the vaccine effectiveness overall, by age group, by influenza season, and by virus type for the subunit and the split vaccines. The split-virion vaccine showed clinical effectiveness for all adults aged ≥50 years, those 50–64 years, and those ≥65 years; for the 2008–2009 and the 2010–2011 influenza seasons; and for influenza types H1N1 and B. The CI for subunit vaccine effectiveness included 0 for all analyses.

Figure 1.

Effectiveness of subunit and split-virion vaccines for all adults aged ≥50 years over the 3 seasons, and vaccine effectiveness (VE) by age group, individual influenza season, and influenza type. VE is shown side by side for comparison. Effectiveness was truncated at 100% and −100%. Confidence intervals are shown in parentheses.

The sensitivity analysis, which included 18 additional participants with missing data and used multiple imputation, produced similar results to that of using the complete data set. The vaccine effectiveness of the split and subunit vaccines was 74.8% (95% CI, 53.3%–89.2%) and 46.3% (95% CI, −4.4% to 75.9%), respectively. The difference in vaccine effectiveness was 28.6% (95% CI, .85%–73.1%).

DISCUSSION

Using prospectively collected data, we found that split-virion vaccines had greater clinical effectiveness than subunit vaccines among adults aged ≥50 years. The difference in vaccine effectiveness of split-virion vaccines was 33.5% compared with subunit vaccines for preventing influenza-associated medically attended visits. A meta-analysis of studies evaluating the antibody responses to hemagglutinin reported similar responses in persons receiving either split-virion or subunit vaccines [2]. There are few investigations comparing T-cell responses between vaccines. One study of 3 commercially available vaccines found very different human T-cell responses that varied with the internal protein content of the vaccines [6]. Greater T-cell responses, as defined by increased interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production, were seen in recipients of the split-virion vaccine preparations [6]. In another study of vaccinated adults aged ≥60 years who were prospectively followed for influenza infection, McElhaney et al [3] reported that a number of cellular responses, including the ratio of IFN-γ to interleukin 10 and the level of granzyme B, were more predictive of protection against infection than pre- or postvaccination antibody titers. Murine models suggest that influenza-specific CD8+ T cells decrease morbidity by reducing viral titers [6]. In healthy human volunteers, reduction of viral replication and protection from disease has been correlated with preexisting cellular immunity [12].

We are aware of only 1 other study that has compared clinical effectiveness of split vs subunit vaccines. A recent European study [13] found no difference in effectiveness between split and subunit vaccines for the 2012–2013 season for any age group. Among adults ≥60 years of age, vaccine effectiveness was 54.1% (95% CI, 16.8%–74.7%) and 64.6% (95% CI, 21.6%–84.0%) for the split and subunit vaccines, respectively. It is unclear why our results differ, although CIs in both studies are wide. The outcomes of the 2 studies differed in that the European study was performed in outpatient clinics. Although we included 1 outpatient clinic and 1 emergency department, 77% of enrolled patients were hospitalized. Hence, split-virion and subunit vaccines may have similar effectiveness for the prevention of mild illness, but split-virion vaccines may be more effective for the prevention of severe disease. Alternatively, the specific vaccines may be more important than the dichotomy between split-virion and subunit vaccines. In our population, most split-virion vaccines were Fluzone (38%) and most subunit vaccines were Fluvirin (99%). The European report did not include specific vaccine formulations. It is also possible that differences in vaccines may be important for only specific influenza viruses or specific age groups.

Clinical effectiveness could also be influenced by the amount of neuraminidase (NA) present in these vaccines. Unlike hemagglutinin, NA content is not standardized, and therefore we do not know the differences in NA content in the vaccines studied. Antibodies to NA fail to prevent infection, but lessen the severity of disease and reduce viral shedding [14]. Hence, NA content could be another reason for differences in clinical effectiveness.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness also relies on the similarity between circulating and vaccine strains. The 2008–2009 [7] and the 2011–2012 [15] influenza season vaccines were good matches for both A strains but poor matches for the B strain alone. The 2010–2011 [16] was a good match for all 3 strains. It is interesting that the greatest difference in clinical vaccine effectiveness was observed for influenza B, for which there was vaccine strain mismatch with the circulating strain in 2 of the 3 study seasons. It is unknown whether specific inactivated vaccines provide better protection against mismatched strains.

This study used the case-positive, control test–negative study design that has been used by both the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness network [17, 18] and the European Influenza Monitoring Vaccine Effectiveness in Europe network [13, 19–21]. This study design uses controls that have presented to the same medical center and have tested negative for influenza. Theoretically, recipients of influenza vaccine may be different from those who have not received influenza vaccine by unmeasured confounders. However, this design controls for factors related to the propensity to seek care with an acute respiratory illness and the need for hospitalizations. In addition, for the major comparison of interest, split vs subunit vaccine, all patients were vaccinated, and there were no clear differences between those who received the 2 types of vaccines.

There are several limitations to this study. We only included 3 influenza seasons in 1 area of the country. The study was also limited by the number of influenza cases detected. The CIs on all estimates, especially in the subgroups, were wide, and sample size was insufficient to assess vaccine differences in the oldest adults. However, patterns in most subgroups were similar. The relatively small sample also increases the likelihood that results are due to chance. However, the findings do conform to our prespecified hypothesis. Last, almost all of the subunit vaccine in this study was from 1 manufacturer; thus, differences observed may be related to the specific vaccine rather than the general vaccine type.

We previously reported that trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines were approximately 60%–70% effective for the prevention of hospitalization in older adults [7, 8]. Those studies were done assuming that all influenza vaccines had similar effectiveness. The current report suggests that all inactivated vaccines may not offer similar protection. However, these results need confirmation from other studies, and should provide the impetus to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of available influenza vaccines. In the meantime, the role of internal viral proteins in influenza vaccines should be explored.

Notes

Disclaimer. The funders did not participate in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; nor preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (grant number 1U181P000184-01 to M. R. G.); RTI International/CDC (contract number 200-2008-24624 to M. R. G.); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number R21HL097334 to Q. C.); and the National Institute on Aging (grant number 1R01AG043419 to H. K. T.). The study was also supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (Vanderbilt Clinical & Translational Research Award grant number 1 UL1 RR024975).

Potential conflicts of interest. H. K. T. has received research funding from Sanofi Pasteur and MedImmune. M. R. G. has received research funding from MedImmune. J. V. W. serves on the scientific advisory board for Quidel. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. About influenza vaccines. Available at: http://www.ifpma.org/resources/influenza-vaccines/influenza-vaccines/about-influenza-vaccine.html. Accessed 9 June 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Beyer WE, Palache AM, Osterhaus AD. Comparison of serology and reactogenicity between influenza subunit vaccines and whole virus or split vaccines: a review and meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Drug Investig 1998; 15:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElhaney JE, Xie D, Hager WD, et al. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J Immunol 2006; 176:6333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murasko DM, Bernstein ED, Gardner EM, et al. Role of humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection from influenza disease after immunization of healthy elderly. Exp Gerontol 2002; 37:427–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jameson J, Cruz J, Ennis FA. Human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte repertoire to influenza A viruses. J Virol 1998; 72:8682–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Co MD, Orphin L, Cruz J, et al. In vitro evidence that commercial influenza vaccines are not similar in their ability to activate human T cell responses. Vaccine 2009; 27:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talbot HK, Griffin MR, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Williams JV, Edwards KM. Effectiveness of seasonal vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in community dwelling older adults. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talbot HK, Zhu Y, Chen Q, Williams JV, Thompson MG, Griffin MR. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine for preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations in adults, 2011–2012 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:1774–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orenstein WA, Bernier RH, Dondero TJ, et al. Field evaluation of vaccine efficacy. Bull World Health Organ 1985; 63:1055–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman J, Hastie T, Ribshirani T. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Software 2010; 33:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson TM, Li CK, Chui CS, et al. Preexisting influenza-specific CD4+ T cells correlate with disease protection against influenza challenge in humans. Nat Med 2012; 18:274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kissling E, Valenciano M, Buchholz U, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates in Europe in a season with three influenza type/subtypes circulating: the I-MOVE multicentre case-control study, influenza season 2012/13. Euro Surveill 2014; 19:pii:20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wohlbold TJ, Krammer F. In the shadow of hemagglutinin: a growing interest in influenza viral neuraminidase and its role as a vaccine antigen. Viruses 2014; 6:2465–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity—United States, September 30-November 24, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:990–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010–2011 influenza (flu) season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pastseasons/1011season.htm Accessed 24 September 2014.

- 17.Flannery B, Thaker SN, Clippard J, et al. Interim estimates of 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin MR, Monto AS, Belongia EA, et al. Effectiveness of non-adjuvanted pandemic influenza A vaccines for preventing pandemic influenza acute respiratory illness visits in 4 U.S. communities. PLoS One 2011; 6:e23085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kissling E, Valenciano M. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe, 2010/11: I-MOVE, a multicentre case-control study. Euro Surveill 2011; 16:pii:19818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissling E, Valenciano M, Falcao J, et al. “I-MOVE” towards monitoring seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccine effectiveness: lessons learnt from a pilot multi-centric case-control study in Europe, 2008–9. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:pii:19388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valenciano M, Kissling E, Cohen JM, et al. Estimates of pandemic influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe, 2009–2010: results of Influenza Monitoring Vaccine Effectiveness in Europe (I-MOVE) multicentre case-control study. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]