Background: MMP-9 cell surface activity promotes tissue remodeling.

Results: Fibroblast cell surface recruitment of MMP-9 via its fibronectin-like domain (FN) by lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3) induces TGF-β activation and myofibroblast differentiation.

Conclusion: We identify a novel mechanism of MMP-9 recruitment to stromal cells that can be modulated by recombinant FN.

Significance: Recombinant FN may allow selective MMP-9 blockade in tumor-associated tissue remodeling.

Keywords: fibroblast, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), myofibroblast, transforming growth factor β (TGF-B), tumor microenvironment

Abstract

Solid tumor growth triggers a wound healing response. Similar to wound healing, fibroblasts in the tumor stroma differentiate into myofibroblasts (also referred to as cancer-associated fibroblasts) primarily, but not exclusively, in response to transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Myofibroblasts in turn enhance tumor progression by remodeling the stroma. Among proteases implicated in stroma remodeling, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP-9, play a prominent role. Recent evidence indicates that MMP-9 recruitment to the tumor cell surface enhances tumor growth and invasion. In the present work, we addressed the potential relevance of MMP-9 recruitment to and activity at the surface of fibroblasts. We show that recruitment of MMP-9 to the fibroblast cell surface occurs through its fibronectin-like (FN) domain and that the molecule responsible for the recruitment is lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3). Functional assays suggest that both pro- and active MMP-9 trigger α-smooth muscle actin expression in cultured fibroblasts, reflecting myofibroblast differentiation, possibly as a result of TGF-β activation. Moreover, the recombinant FN domain inhibited both MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation and α-smooth muscle actin expression by displacing MMP-9 from the fibroblast cell surface. Together our results uncover LH3 as a new docking receptor of MMP-9 on the fibroblast cell surface and demonstrate that the MMP-9 FN domain is essential for the interaction. They also show that the recombinant FN domain inhibits MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation and fibroblast differentiation, providing a potentially attractive therapeutic reagent toward attenuating tumor progression where MMP-9 activity is strongly implicated.

Introduction

Tumor cell interactions with host tissue stroma play a key role in determining tumor progression that culminates in metastatic growth. It is well established that malignant tumor growth initiates a wound healing response that maintains a state of tissue remodeling, which favors tumor survival, invasion, and dissemination. Orchestration of tumor-associated tissue remodeling is mediated in part by tumor cells and in part by a variety of recruited host tissue cells, including various leukocyte subsets and mesenchymal cell subtypes ranging from mesenchymal stem cells to myofibroblasts (1–3). Most of these cells participate in generating soluble mediators that include a plethora of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and enzymes. Among the proteolytic enzymes implicated in tumor-host cross-talk are matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs),2 a large family of zinc-dependent extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading endopeptidases that play a key role in tissue remodeling during development and repair (4). The majority of MMPs are secreted, but at least a fraction of their proteolytic activity is observed at the cell surface where they can be anchored by a variety of cell surface receptors to provide controlled degradation of the ECM and activation of a variety of latent growth factors (5). Whether or not cell surface anchoring of secreted MMPs occurs exclusively in autocrine fashion in the context of tissue remodeling or whether it may also occur in paracrine fashion whereby MMP-anchoring cells are distinct from MMP-secreting cells remains to be clarified.

MMP-9, also known as gelatinase B, has been shown to play a prominent role in the progression of numerous tumor types by promoting tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis (6, 7). Similar to other MMPs, MMP-9 is synthesized as an inactive zymogen, or pro-MMP-9, composed of a propeptide, a catalytic domain containing fibronectin-like (FN) repeats, a linker region or hinge domain, and a C-terminal hemopexin-like (HEX) domain thought to be necessary for substrate recognition (4). The FN domain, which is found only in MMP-9 and MMP-2, is composed of three tandem fibronectin type II-like motifs that form a collagen-binding domain critical for the positioning of substrates for subsequent cleavage (8). The collagen-binding domain of MMP-9 has been shown to bind gelatin (9), elastin, and both native and denatured types I, II, III, IV, and V collagen (8, 10). Each fibronectin type II-like module displays binding specialization, which generates exosites specific for other ligands degraded by the protease (10). Cooperation among collagen binding sites within these three modules increases substrate specificity and thereby has the potential to localize the enzyme to collagen either in the extracellular matrix or on the cell surface (11).

MMP-9 expression is low or absent in normal quiescent tissues but is strongly induced under conditions that trigger tissue remodeling, including development, wound healing, and tumor invasion. MMP-9 is produced by tumor-associated host tissue cells, including endothelial cells, various leukocytes, and tumor cells themselves, and is thought to promote tumor growth and metastasis (4, 6, 12–14). Several secreted MMPs, including pro-MMP-9, can at least transiently be anchored to the cell surface, which directs their proteolytic activity toward pericellular substrates and may provide protection from natural inhibitors. However, the mechanisms that underlie their association with the cell membrane appear to be diverse and remain to be fully explored (5, 15, 16). Thus far, MMP-9 has been shown to use among others the cell surface hyaluronan receptor CD44 as a docking molecule in certain tumor cell types and keratinocytes (17). This association stabilizes MMP-9 proteolytic activity at the cell surface to facilitate controlled collagen IV degradation and to promote invasion (17). In addition, CD44-associated MMP-9 as well as MMP-2 can cleave and activate latent TGF-β1 and -2 (18). Thus, coordination of CD44, MMP-9, and TGF-β function may provide a physiological mechanism of tissue remodeling that can be adopted by malignant cells to promote their own growth and dissemination (18, 19). As key regulators of ECM turnover, fibroblasts may include MMP-9 in their arsenal of tissue remodeling reagents. However, mechanisms that govern putative MMP-9 association with the surface of normal stromal cells, including fibroblasts, remain to be elucidated. Fibroblasts produce low amounts of MMP-9, suggesting that they may recruit tumor cell or leukocyte-derived MMP-9 to their own cell surface to promote ECM remodeling by harnessing its proteolytic activity.

In the present work, we show that MMP-9 produced by tumor cells is recruited to the fibroblast surface and that recruitment requires the FNII repeats or collagen-binding domain of MMP-9. We demonstrate that the structure that mediates MMP-9 docking to the fibroblast surface is provided by lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3), which displays lysyl hydroxylase as well as galactosyl- and glucosyltransferase activity (20). LH3 is expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum but is also associated with the plasma membrane via collagenous proteins (21). We show that LH3-mediated MMP-9 recruitment contributes to TGF-β activation, which stimulates fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts. Tumor cells and leukocytes may thus provide a source of MMP-9 that fibroblasts can recruit and use to activate TGF-β and stimulate their own differentiation.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Lines

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T, fibrosarcoma (HT1080), transformed mink lung epithelial cells (TMLC), glioblastoma (U251), osteosarcoma (U2OS), breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB231), human skin fibroblasts (HSF), human lung embryonic fibroblasts (MRC-5), and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultures in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Chemical Compounds

Chemical compounds used included:4-aminophenylmercuric acetate (164610, Calbiochem), Complete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitors (11836170001, Roche Applied Science), FcR blocking reagent (130-059-901, Miltenyi Biotec), FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (E2692, Promega), Interferin (409-01, Polyplus Transfection), Sulfo-SBED Biotin Label Transfer Reagent (33034, Pierce), SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (34080, Thermo Scientific Pierce), human TGF-β1 (100-B-001, R&D Systems), Duolink II PLA Probe Anti-Mouse PLUS (DUO92001, Sigma-Aldrich), Duolink II PLA Probe Anti-Rabbit MINUS (DUO92005, Sigma-Aldrich), Duolink In Situ Detection Reagents Red (DUO92008, Sigma-Aldrich), and procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3 (PLOD3) (human; three unique 27-mer siRNA duplexes) (SR305927, Origene).

Antibodies

Antibodies used were as follows: anti-HA-agarose matrix (11 815 016 001, Roche Applied Science), anti-LH3 (11027-1-AP, ProteinTech), anti-MMP-9 (MS-817-P0, Thermo Scientific), anti-α-SMA (A2547, Sigma), anti-tubulin (CP06, Calbiochem), anti-transferrin receptor (13-6800, Invitrogen), anti-TGF-β1,2,3 (MAB1835, R&D Systems), anti-v5 (R960-25, Invitrogen), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A21202, Invitrogen), Ni-NTA-agarose beads (30210, Qiagen), streptavidin-agarose beads (DAM1467561, Millipore), anti-v5-agarose beads (A7345, Sigma), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse (NA931V, GE Healthcare), and goat anti-rabbit (P0448, Dako).

Expression Constructs

Wild type (WT) pro-MMP-9 and the different MMP-9 constructs, including the catalytically dead protein containing the E402Q mutation, the FN domain composed of the fibronectin type II-like motifs (FN223–389), the hemopexin homology domain (HEX520–707), the ΔFN or MMP-9Δ223–389 mutant lacking the FN domain, the ΔHEX or MMP-9Δ520–707 mutant lacking the hemopexin homology domain, and CD5, were inserted into the pLIVC vector, derived from the pLVTHM lentiviral vector by the removal of the shRNA cassette and GFP gene and insertion of a phosphoglycerate kinase-puromycin cassette. All constructs were 3′ tagged with sequences encoding 6 histidines and the v5 peptide.

Virus Production

60% confluent HEK293T cells in a 100-mm dish were transfected with 1.25 μg of pMD2G (envelope plasmid), 3.75 μg of pCMVs (packaging plasmid), and 5 μg of pLIVC (transfer vector) containing MMP-9 or the different mutants using FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent at a ratio of 1:3 and incubated at 37 °C. Lentiviruses were collected after 48 h, filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation.

Retroviral Infection

Target cells (CHO, U2OS, HT1080, and MRC-5) at 40% confluence in 6 wells were washed with PBS and infected in two rounds of 8-h intervals with lentiviruses using Polybrene (1:1000) overnight at 37 °C. Cells were then washed with PBS and transferred to a 100-mm dish with fresh medium. On the following day, cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/μl for CHO and U2OS and 2 μg/μl for MRC-5).

His Tag Purification

Stable transfectants of each His-tagged construct were established in U2OS and CHO cells. Purification was performed using the histidine tag and high affinity nickel beads as follows. The supernatant of CHO cells provided by Evitria (Zürich, Switzerland) was incubated with Ni-NTA-agarose beads (2 ml of beads for 1 liter of sample), which were then washed with PBS and in washing solution (5 mm imidazole, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 200 mm NaCl). Purified proteins were eluted in 20 mm and 200 mm imidazole, and fractions were concentrated with Amicon centrifugal filters (Millipore) depending on the molecular weight (50,000 nominal molecular weight limit for pro-MMP-9 and ΔFN and 3000 nominal molecular weight limit for FN). Protein concentration was determined by densitometry using ImageJ.

Pro-MMP-9 Activation

Activation of pro-MMP-9 was performed directly on nickel beads using 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate. 35 mg of 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate was dissolved in 10 ml of 0.1 m NaOH and diluted in TTC reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm CaCl2, and 0.05% Triton X-100) to obtain a 2.5 mm solution. Pro-MMP-9 bound to Ni-NTA-agarose beads was incubated with this solution at 37 °C for 3 h and eluted as described before.

Recruitment Assay

Tumor cell lines and fibroblasts were incubated overnight at 37 °C with filtered conditioned medium from U2OS cells stably expressing recombinant MMP-9 or its different mutants or with 0.5 μg/ml purified peptides. The following day, cells were lysed using lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100) containing Complete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitors. Immunoblotting of conditioned medium and cell lysates was performed using anti-v5 antibody, and the ImageJ program was used for recruitment quantification.

Cell Fractionation

Cells grown in 2 × 150-mm dishes until 60–70% confluent were washed and scraped in cold PBS and centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g at 4 °C. Membranes were sensitized by resuspending cell pellets in 1 ml of homogenization buffer (250 mm sucrose, 3 mm imidazole, and phosphatase and protease inhibitor mixtures, pH 7.4). Postnuclear supernatant was obtained by mechanical disruption of cells with a 22-gauge needle and centrifugation for 10 min at 600 × g at 4 °C. Postnuclear supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation for 45 min at 100,000 × g at 4 °C to separate cytosol (supernatant) from membrane (pellet) fractions. Membranes were washed twice with homogenization buffer and solubilized using lysis buffer containing Complete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitors.

Western Blot

Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures. The following antibody concentrations were used: anti-v5, 1:5000; anti-transferrin receptor, 1:1000; anti-LH3, 1:500; anti-α-SMA, 1:5000; anti-tubulin, 1:4000; anti-MMP-9, 1:200; HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse, 1:20,000; and goat anti-rabbit, 1:20,000. ECL was revealed using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate.

Live Immunofluorescence

MRC-5 fibroblasts were grown on glass coverslips until they reached confluence. Cells were treated with pro-MMP-9, FN, E402Q, ΔFN, and CD5 and incubated with anti-v5 antibody (1:1500) for 1 h at 4 °C, washed with PBS, and further incubated with secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:1500) for 1 h at 4 °C. Antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer (PBS and 10% FBS). Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and mounted using Immuno-Mount. DAPI (Roche Applied Science) was used to visualize the nuclei. Images were acquired with a Leica SP5 AOBS confocal microscope.

Mass Spectrometry

Confluent MRC-5 cells in square plates (Nunc) were treated with 50 μg of Sulfo-SBED Biotin Label Transfer Reagent-labeled MMP-9, FN, and ΔFN at 37 °C for 4 h. Cells were washed in the dark and cross-linked applying UV light at 365 nm for 8 min before lysis. Finally, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using v5-agarose beads and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis at the Protein Analysis Facility (Lausanne, Switzerland).

Luciferase Assay

The luciferase assay system (E1501, Promega) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, TMLC transfected with the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter responsive to TGF-β and linked to a luciferase reporter system were plated at 3 × 105 cells/ml in 24 wells for 6 h. MRC-5-conditioned medium collected after 3 days was incubated with TMLC at 37 °C for 20 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and lysed with 1× lysis buffer for 20 min on ice. 20 μl of cell lysates was mixed with 90 μl of luciferase substrate. Luminescence was read at 570 nm using a Synergy MX luminometer for 2 s with autosensitivity.

Immunoprecipitation

Confluent MRC-5 cells in a 25-cm dish were treated with 13 μg of Sulfo-SBED-labeled v5-tagged MMP-9, FN, and ΔFN overnight at 37 °C. The interaction was cross-linked with UV light at 365 nm for 8 min after which MRC-5 cells were lysed with lysis buffer. 4 mg of cell lysates was precleared with HA-agarose matrix for 1 h at 4 °C and then immunoprecipitated with anti-v5-agarose beads overnight at 4 °C. Beads were washed seven times with lysis buffer and a final wash with PBS, and proteins were eluted by boiling the beads for 5 min in sample buffer. Purified complexes were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-LH3 antibody.

LH3 Knockdown

MRC-5 cells in 6-well plates at 30% confluence were transfected with 1 nm siRNA pool against LH3. After 48–72 h, 0.5 μg/ml purified v5-tagged MMP-9, FN, or ΔFN was incubated with control and LH3-depleted MRC-5 cells overnight at 37 °C.

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

MRC-5 cells at 80% confluence in 6-well plates containing 8-mm coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies mouse anti-MMP-9 (1:300), rabbit anti-LH3 (1:50), and mouse anti-v5 (1:1500) for 1 h at room temperature and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PIPES buffer, pH 6.8 for 12 min at room temperature. PLA amplification was labeled with Alexa Fluor 594. Coverslips were counterstained with DAPI, mounted, and imaged using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal fluorescence microscope with a 40× oil immersion objective. The resulting images were analyzed using a script written in ImageJ macro language.

FACS

MRC-5 cells were incubated with v5-tagged MMP-9 and ΔFN overnight at 37 °C. Cells were then scraped in PBS, blocked with FcR blocking reagent (1:10 diluted in PBS) for 30 min at 4 °C, and incubated with anti-v5 or an irrelevant mouse isotype-matched antibody (1:400) for 3 h followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody (1:400) for 30 min at room temperature. DAPI was used to discriminate between living and dead cells. Cells were sorted using a Beckman Coulter Gallios flow cytometry system and analyzed using FlowJo_V10.

Statistical Analysis

Graphs and statistical analysis were carried out using GraphPad Prism® 6.0 software. Results represent mean values ±S.E. in all graphs. p values were as follows: ns, p > 0.05; *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001.

Results

Pro-MMP-9 Is Recruited to the Fibroblast Cell Surface

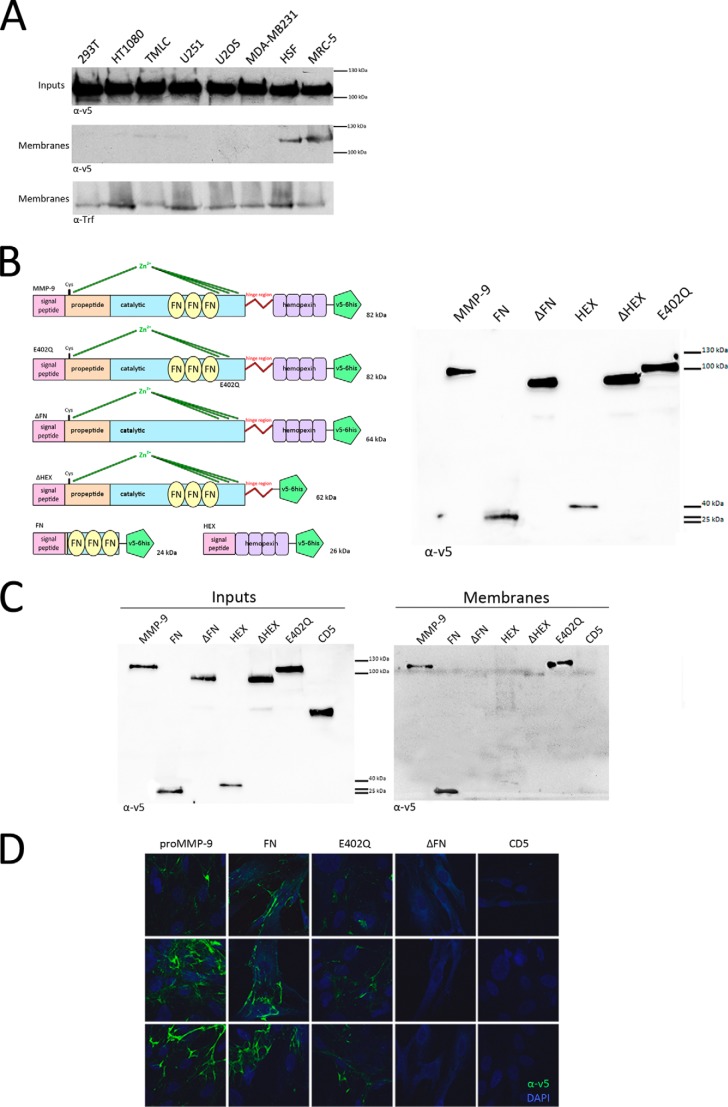

To compare association of MMP-9 with the surface of tumor versus stromal cells, we incubated HEK293T, HT1080 (fibrosarcoma), TMLC, U251 (glioblastoma), U2OS (osteosarcoma), MDA-MB231 (breast carcinoma), and immortalized HSF as well as MRC-5 (human fetal lung fibroblasts) in conditioned medium of U2OS cells engineered to secrete v5-tagged pro-MMP-9. Following overnight incubation, cell membranes were isolated by cell fractionation, and protein recruitment was assessed by anti-v5 antibody blot analysis. We observed pro-MMP-9 to be more markedly recruited to fibroblast membranes (HSF and MRC-5) than to those of the different tumor cell lines (Fig. 1A). Cell fractionation analysis confirmed that pro-MMP-9 is recruited to fibroblast membranes.

FIGURE 1.

Pro-MMP-9 is preferentially recruited via its FN domain to fibroblasts than to the surface of a panel of diverse tumor cell lines. A, cells were incubated in U2OS-conditioned medium containing v5-tagged pro-MMP-9 (Inputs), and equal amounts of corresponding membrane fractions (Membranes) were loaded onto gels. A representative anti-v5 antibody immunoblot of membrane preparations from the indicated tumor cell lines as well as HSF and MRC-5 fibroblasts from three independent experiments is shown. Transferrin receptor (Trf) was used as a membrane equal loading control. B, MMP-9 and its mutants. Shown is a schematic representation of wild type pro-MMP-9; the catalytically dead mutant carrying the E402Q substitution within the catalytic domain; ΔFN, which lacks the FN domain; ΔHEX, which lacks the hemopexin homology domain; FN, which is composed of the fibronectin II domain (FN223–389) only; and HEX, which is composed of the hemopexin homology domain (HEX520–707) only. All constructs were tagged at their 3′ extremity with sequences encoding 6 histidine residues and the v5 peptide. All cDNAs were inserted into the pLIVC retroviral vector and stably expressed in CHO cells. Immunoblots of v5-tagged mutants expressed in U20S transfectant-conditioned culture media are shown (right panel). C and D, the FN domain of MMP-9 is necessary and sufficient for its recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface. C, MRC-5 cells were incubated in conditioned culture media from U2OS cells engineered to express recombinant v5-tagged pro-MMP-9 or the different mutants (FN, ΔHEX, ΔFN, HEX, and E402Q (Inputs)) and lysed, and equal amounts of cell lysates were loaded onto gels. A representative anti-v5 antibody immunoblot of MRC-5 cell membranes from three independent experiments shows that pro-MMP-9 and mutants containing the FN domain (FN, ΔHEX, and E402Q) are recruited to the MRC-5 cell surface, whereas those lacking the FN domain (ΔFN and HEX) are not at all or weakly so. D, MRC-5 cells were incubated in conditioned culture medium of U2OS cells expressing recombinant v5-tagged pro-MMP-9 or the different mutants (FN, E402Q, and ΔFN) and CD5, which was used as negative control, and anti-v5 antibody reactivity with intact cells was assessed by immunofluorescence. Only pro-MMP-9 and mutants containing the FN domain (FN and E402Q) are recruited to the MRC-5 cell surface. DAPI (blue) was used to visualize nuclei.

The FN Domain of MMP-9 Is Necessary and Sufficient for Its Recruitment to the Fibroblast Cell Surface

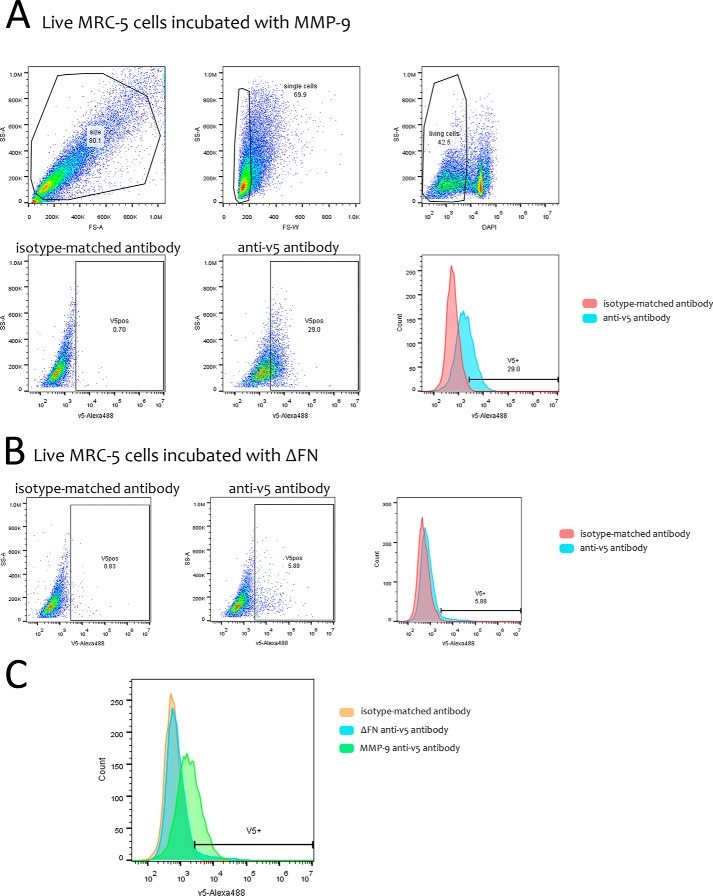

Pro-MMP-9 recruitment to the cell surface has been proposed to be mediated by its HEX domain (13). However, it is possible that different MMP domains may be responsible for MMP-9 docking to the surface of different cell types. Accordingly, we asked whether the HEX or other domains of MMP-9 mediates its recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface. We therefore engineered a series of deletion mutants corresponding to defined MMP-9 domains tagged with sequences encoding 6 histidines and the v5 peptide. The mutants included a catalytically dead protein containing the E402Q mutation within the catalytic domain, ΔFN lacking the FNII repeat collagen-binding domain, ΔHEX lacking the hemopexin homology domain; FN composed of fibronectin type II-like repeats (FN223–389) only, and HEX composed of the hemopexin homology domain (HEX520–707) only (Fig. 1B). All mutants were inserted into the pLIVC retroviral vector and stably produced in CHO cells. Each mutant was compared with v5-tagged pro-MMP-9 for recruitment to fibroblasts by incubating MRC-5 cells in the corresponding CHO cell-conditioned medium overnight at 37 °C and subsequently performing Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis of MRC-5 membrane fractions and intact cells, respectively. Anti-v5 antibody Western blot analysis of membrane fractions showed that all proteins encoded by constructs containing the FN domain (pro-MMP-9, FN, ΔHEX, and E402Q) were recruited to MRC-5 fibroblasts, whereas those lacking the FN domain were not (Fig. 1C). Immunofluorescence analysis using anti-v5 antibody confirmed the observation that both pro-MMP-9 and the inactive E402Q mutant are recruited to the MRC-5 cell surface. The FN domain alone was also, whereas constructs lacking the FN motifs, including ΔFN and CD5, used as a negative unrelated protein control were not (Fig. 1D). The observation that ΔHEX is less strongly detected than functional or catalytically dead MMP-9 on the fibroblast cell surface as assessed by Western blot analysis suggests that the presence of the hemopexin domain may help optimize recruitment. However, we did not observe cell surface recruitment of the HEX domain alone. To further reinforce the notion that MMP-9 binds to the cell surface via its FN domain, FACS analysis of non-permeabilized MRC-5 cells incubated with v5-tagged MMP-9 or the ΔFN mutant was performed. The results clearly indicate that MMP-9 but not the ΔFN mutant is recruited to MRC-5 cell surface membrane (Fig. 2). Together, these observations indicate that it is primarily the FN domain of MMP-9 that recognizes structures on the fibroblast cell surface.

FIGURE 2.

FACS analysis of v5-tagged MMP-9 variant recruitment to living MRC-5 cells. A, live MRC-5 cells incubated with v5-tagged MMP-9 were stained with mouse anti-v5 or an irrelevant mouse isotype-matched antibody followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody. Single cells (69.9) were gated after doublet exclusion, and DAPI-negative cells (42.5) were considered to be live. The shift in the histogram between isotype-matched (0.7) and anti-v5 antibody (29.0) profiles shows MMP-9 presence on the MRC-5 cell surface. B, live MRC-5 cells incubated with v5-tagged ΔFN were stained with anti-v5 or an irrelevant mouse isotype-matched antibody followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. No shift between isotype-matched (0.83) and anti-v5 antibody peaks (5.89) is observed. C, superposition of isotype-matched (orange) and anti-v5 antibody (ΔFN, blue; MMP-9, green) staining profiles. SS-A, side scatter area; FS-A, forward scatter area; FS-W, forward scatter width.

MMP-9 Activity Promotes Latent TGF-β Activation and Induces α-SMA Expression in Resting Fibroblasts

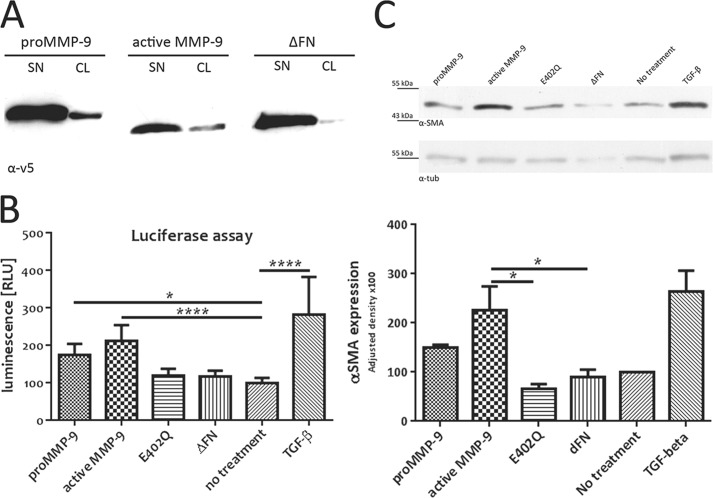

To address the physiological significance of MMP-9 recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface, we first determined whether the active or only the precursor form of MMP-9 is recruited to the MRC-5 cell surface. Recombinant pro-MMP-9 from conditioned culture medium of stably transfected CHO cells was activated using 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate on nickel beads during the His tag purification step. Incubation of MRC-5 cells with pro-MMP-9, active MMP-9, and ΔFN and subsequent anti-v5 antibody blot analysis of cell lysates revealed that both pro- and active MMP-9 are recruited to the fibroblast cell surface (Fig. 3A). This observation suggests that the proteolytically active form of MMP-9 can be retained at the cell membrane as a result of interactions mediated by its FN domain.

FIGURE 3.

MMP-9 activity promotes latent TGF-β activation and induces α-SMA expression in cultured fibroblasts. A, active MMP-9 is recruited to fibroblast cell surface. MRC-5 cells were incubated in conditioned culture media (SN) containing 0.5 μg/ml of purified pro- or active MMP-9 or the ΔFN mutant, and equal amounts of corresponding cell lysates (CL) were loaded onto gels. Recruitment to the MRC-5 cell surface was verified by anti-v5 antibody immunoblotting. B, MMP-9 activity promotes TGF-β activation in cultured MRC-5 cells. Conditioned culture medium of MRC-5 cells incubated for 72 h with 0.5 μg/ml pro-MMP-9, active MMP-9, E402Q, ΔFN, or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) was collected for luciferase assays using TGF-β-responsive TMLC. Luminescence reflecting TGF-β activity was quantified by relative light units (RLU). C, MMP-9 induces α-SMA expression in resting MRC-5 cells. MRC-5 cells were incubated for 72 h with 0.5 μg/ml pro-MMP-9, active MMP-9, E402Q, ΔFN, or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml). A representative anti-α-SMA antibody immunoblot of equal amounts of MRC-5 cell lysates from four independent experiments (upper panel) is shown. Analysis of α-SMA expression from four independent experiments (lower panel) is shown. Expression quantification was normalized to tubulin (tub). Results represent mean values ±S.E. (error bars). *, p ≤ 0.05; ****, p ≤ 0.0001.

MMP-9 has been shown to play a prominent role in tumor growth and invasion in part by activating latent TGF-β in a functional complex with CD44 at the surface of keratinocytes and selected tumor cells (18). Hence, we asked whether the presence of cell surface-anchored pro-MMP-9 and its active form might induce TGF-β activation in MRC-5-conditioned culture medium. Accordingly, we performed a functional TGF-β assay using TMLC stably transfected with the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter, which is responsive to active TGF-β and linked to the luciferase reporter gene (22). MRC-5 fibroblasts were treated for 24 or 72 h with purified recombinant MMP-9, its different mutants, or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) used as a positive control. MMP-9 derivatives included pro-MMP-9, active MMP-9, the catalytically inactive E402Q mutant, and ΔFN. The corresponding MRC-5-conditioned media were used for luciferase reporter assays in TMLC. We observed that both pro- and active MMP-9 induce TGF-β activation in cultured MRC-5 fibroblasts, whereas the inactive mutants E402Q and ΔFN do not enhance baseline MRC-5-derived TGF-β activity (Fig. 3B). Moreover 24- and 72-h exposure to recombinant MMP-9 and TGF-β resulted in roughly comparable induction of luciferase reporter expression. These observations support the notion that the increase in TGF-β activation is due to catalytic MMP-9 activity.

TGF-β is a potent inducer of fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts. We therefore addressed the possibility that MMP-9 activity at the surface of MRC-5 cells may facilitate their differentiation into myofibroblasts. Differentiation was assessed by incubating resting MRC-5 cells for 72 h with purified pro-MMP-9, active MMP-9, the catalytically inactive E402Q mutant, ΔFN, or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) as a positive control. Cells were then lysed, and expression of α-SMA, a reliable myofibroblast marker that is weakly expressed in MRC-5 cells, was assessed. Incubation with pro- and active MMP-9 led to an increase in α-SMA expression in cultured MRC-5 fibroblasts (Fig. 3C), whereas incubation with E402Q and ΔFN mutants failed to do so. These observations support the notion that MMP-9 activity promotes differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts.

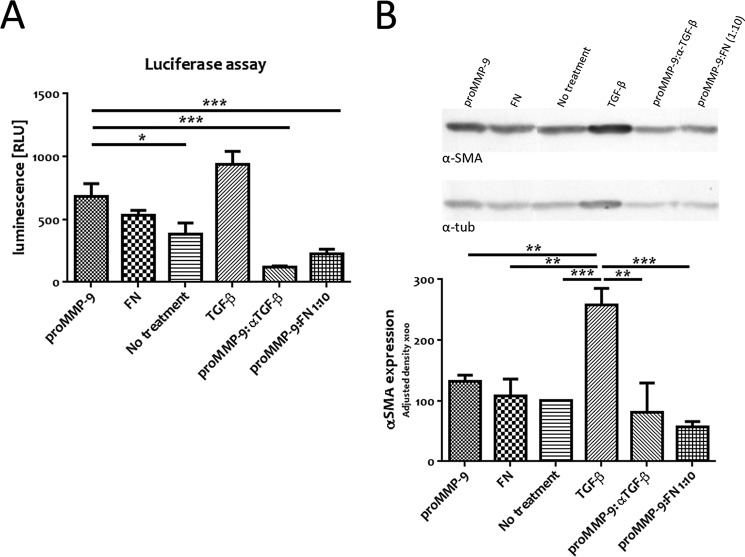

The FN Domain Behaves as Competitive Inhibitor of MMP-9 and Decreases Both TGF-β Activation and α-SMA Expression in Resting Fibroblasts

Given that the FN domain is necessary and sufficient for MMP-9 recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface, we interrogated its ability to compete with MMP-9 for cell membrane docking and to inhibit MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation. We therefore incubated MRC-5 cells for 72 h with active MMP-9, pro-MMP-9, the FN domain only (Fig. 4A, FN), pro-MMP-9 with anti-TGF-β antibody (proMMP-9:αTGF-β), pro-MMP-9 with a 10-fold excess of the FN domain (proMMP-9:FN 1:10) that corresponds to a molar ratio of 1:34, or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) as a positive control and assessed the corresponding conditioned culture media for luciferase reporter induction. Whereas the FN domain alone had no effect on TGF-β activation (Fig. 4A) and displayed no catalytic activity as assessed by gelatin zymography (data not shown), a 34-fold molar excess of the FN domain in the presence of pro-MMP-9 decreased TGF-β activation almost as strongly as a neutralizing anti-TGF-β antibody. Thus, exogenously added recombinant FN domain of MMP-9 can inhibit MMP-9 activity as measured by TGF-β activation.

FIGURE 4.

The FN domain behaves as a competitive inhibitor of pro-MMP-9 docking and blocks both TGF-β activation and α-SMA expression in cultured fibroblasts. A, recombinant FN domain abrogates MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation in MRC-5 cells. Conditioned culture media of MRC-5 cells incubated for 72 h with 0.5 μg/ml pro-MMP-9, FN, pro-MMP-9 with an anti-TGF-β antibody (proMMP-9:αTGF-β), pro-MMP-9 with an excess of the FN domain (proMMP-9:FN 1:10 or 1:34 molar ratio), or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) were subjected to luciferase assays using TGF-β-responsive TMLC. Luminescence reflecting TGF-β activity was quantified by relative light units (RLU). B, recombinant FN domain blocks MMP-9-dependent α-SMA expression in cultured MRC-5 cells. MRC-5 cells were incubated for 72 h with 0.5 μg/ml pro-MMP-9, FN, pro-MMP-9 with an anti-TGF-β antibody (proMMP-9:αTGF-β), pro-MMP-9 with an excess of the FN domain (proMMP-9:FN 1:10), or TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml). A representative anti-α-SMA antibody immunoblot of equal amounts of MRC-5 cell lysates from four independent experiments (upper panel) is shown. Analysis of α-SMA expression from three independent experiments (lower panel) is shown. Expression quantification was normalized to tubulin (tub). Results represent mean values ±S.E. (error bars). *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

We next asked whether inhibition of TGF-β activation by the FN domain could prevent α-SMA expression in resting fibroblasts, which would reflect abrogation of their differentiation into myofibroblasts. As described above, MRC-5 fibroblasts were treated for 72 h with pro-MMP-9, the FN domain only (Fig. 4B, FN), pro-MMP-9 in the presence of anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody (proMMP-9:αTGF-β), pro-MMP-9 in the presence of an excess of the FN domain (proMMP-9:FN 1:10), or the positive control TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml). Cells remained viable after the 72-h treatment, and cell lysis was performed to assess α-SMA expression. We observed that α-SMA expression in MRC-5 treated with the FN domain alone was comparable with that in untreated MRC-5 (Fig. 4B). However, the FN domain added in 34-fold molar excess of pro-MMP-9 significantly reduced α-SMA expression even more potently so than the neutralizing anti-TGF-β antibody. The fact that MMP-9-induced α-SMA expression can be inhibited by neutralizing anti-TGF-β antibody indicates that MMP-9-mediated differentiation of MRC-5 into α-SMA-expressing myofibroblasts under our culture conditions occurs in large part through the TGF-β pathway. Moreover, abrogation by excess recombinant FN domain of the ability of MMP-9 to induce α-SMA expression in cultured fibroblasts suggests that the FN domain can inhibit MMP-9 activity at the fibroblast cell surface.

LH3 Provides the Docking Mechanism for MMP-9 Cell Surface Association via the FN Domain

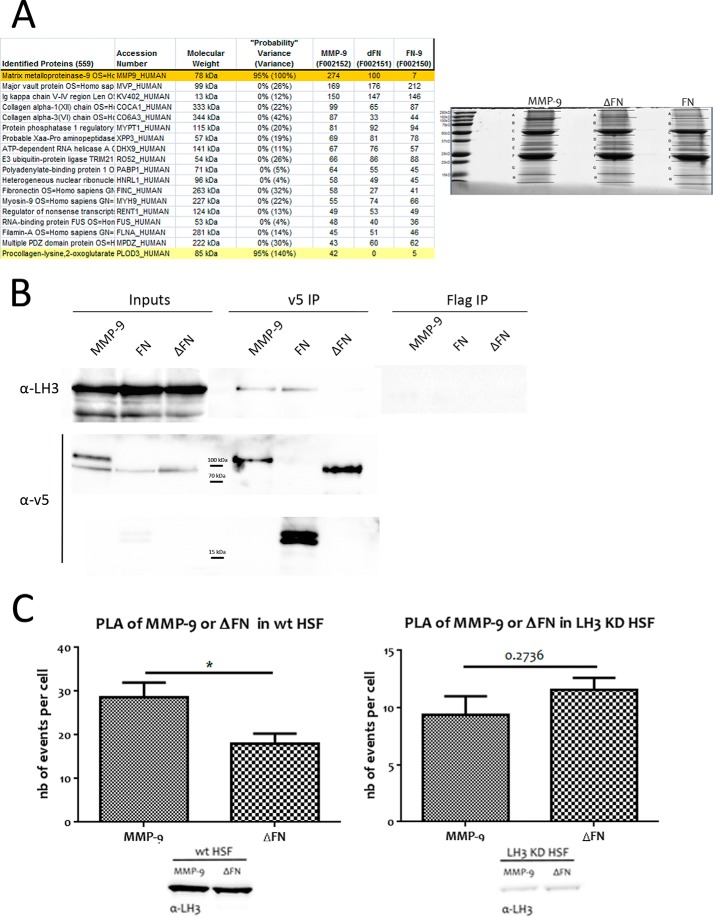

CD44 has been shown to be an MMP-9 docking molecule at the surface of TA3 mouse mammary carcinoma, melanoma cells, and normal keratinocytes (17). However, CD44 does not appear to be necessary for MMP-9 recruitment to the fibroblast membrane (data not shown), and recruitment therefore occurs by a CD44-independent mechanism. To identify candidate MMP-9 docking molecules on the fibroblast cell surface, we performed mass spectrometry analysis of an anti-v5 antibody pulldown of MMP-9, FN, and ΔFN cross-linked to MRC-5 cells. MRC-5 cells were incubated with MMP-9, FN, and ΔFN proteins and labeled with Sulfo-SBED Biotin Label Transfer Reagent after which the putative interactions were cross-linked by UV light at 365 nm for 8 min. Anti-v5 antibody was then used for immunoprecipitation from the corresponding cell lysates (Fig. 5 A), and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to shotgun mass spectrometry. Analysis of the pulldown revealed PLOD3_HUMAN, also known as LH3, to be a specific candidate binding partner of MMP-9 and the FN domain (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

LH3 provides a cell surface docking mechanism for MMP-9 by recognizing its FN domain. A, mass spectrometry analysis. PLOD3_HUMAN (LH3) appeared to be specifically pulled down by MMP-9 and the FN domain according to mass spectrometry analysis with 95% probability (140% probability variance). Coomassie Blue staining of the pulldown of labeled MMP-9, FN, and ΔFN is shown (right panel). B, MMP-9 interacts with endogenous LH3 at the fibroblast cell surface via its FN domain. A representative anti-LH3 antibody immunoblot of anti-v5 antibody immunoprecipitates shows that endogenous LH3 is immunoprecipitated with both v5-tagged MMP-9 and its recombinant FN domain (v5 IP MMP-9 and FN), confirming the specificity of the interaction via fibronectin type II-like motifs. Anti-FLAG antibody immunoprecipitations (IP) constitute a control. C, interaction between MMP-9 and LH3 decreases upon LH3 depletion. PLA analysis between v5-tagged MMP-9 or ΔFN and endogenous LH3 in HSF showing specificity of the interaction between LH3 and the FN domain of MMP-9 (left panel) and impairment of the interaction when LH3 is depleted (KD) (right panel). nb, number. Results represent mean values ±S.E. (error bars). *, p ≤ 0.05.

To verify the interaction between MMP-9 and LH3, we incubated MRC-5 cells with recombinant v5-tagged and Sulfo-SBED-labeled MMP-9, FN, or ΔFN for 4 h at 37 °C, cross-linked the interaction, and collected cell lysates to perform anti-v5 and anti-FLAG control antibody immunoprecipitation. We used anti-endogenous LH3 antibody to reveal the interaction. By immunoblot analysis, we could clearly demonstrate that both v5-tagged MMP-9 and the FN domain can immunoprecipitate endogenous LH3, whereas ΔFN cannot (Fig. 5B). Thus, MMP-9 forms a complex with LH3 via its FN domain.

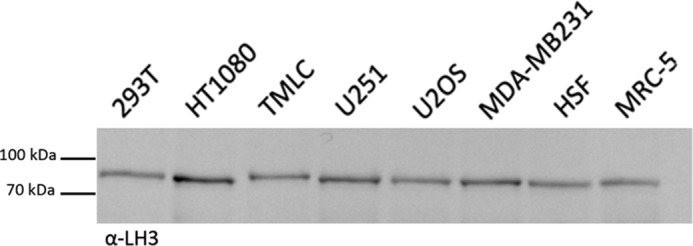

To further explore this interaction in vivo without resorting to cross-linking, we performed PLAs. HSF were treated with v5-tagged MMP-9 or ΔFN overnight at 37 °C and the following day incubated with mouse anti-v5 and rabbit anti-LH3 antibody prior to paraformaldehyde fixation and subjection to proximity ligation (see “Experimental Procedures”). We compared v5-tagged MMP-9 and ΔFN interaction with endogenous LH3 by quantifying the number of events per cell (reflected by fluorescence signals) in WT HSF or in HSF depleted of LH3. We observed a significantly higher number of events in HSF incubated with MMP-9 than in HSF treated with ΔFN (Fig. 5C, left panel), confirming the requirement of the FN domain for interaction with LH3. Moreover, interaction was abrogated in HSF depleted of LH3 as we detected no significant difference between MMP-9 and ΔFN when LH3 was down-regulated (Fig. 5C, right panel). These observations support the notion that LH3 constitutes a hitherto undiscovered MMP-9 docking structure that specifically recognizes its FN domain. It is noteworthy that LH3 was expressed by tumor cell lines that did not recruit MMP-9 (Fig. 6), suggesting that the observed interaction in MRC5 cells may be due to fibroblast-specific post-translational modifications of LH3.

FIGURE 6.

Recruitment of MMP-9 to fibroblast cell surface does not depend merely on LH3 expression at the cell membrane. Tumor cell lines and fibroblasts used in Fig. 1A were tested for LH3 expression at their membrane. Equal amounts of corresponding membrane fractions were loaded onto gels. A representative anti-LH3 antibody immunoblot of membrane preparations from the indicated tumor cell lines as well as HSF and MRC-5 fibroblasts from three independent experiments is shown.

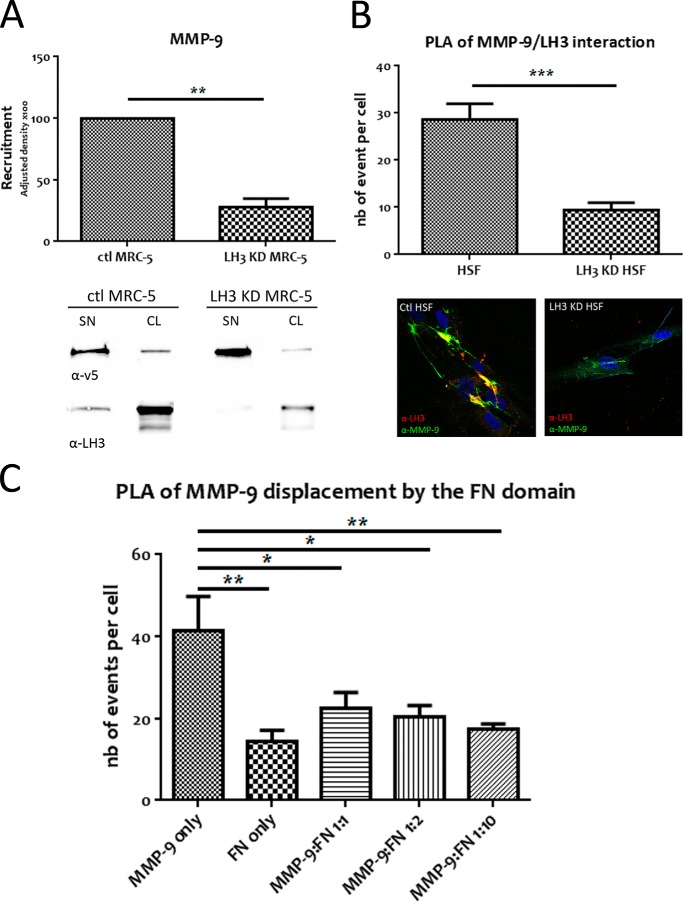

LH3 Down-regulation Decreases MMP-9 Recruitment to MRC-5 and Thus MMP-9/LH3 Interaction

By identifying the interaction between the FN domain of MMP-9 and LH3, we predicted that down-regulation of LH3 in MRC-5 cells would decrease MMP-9 recruitment. We therefore depleted MRC-5 cells of LH3 and compared recruitment of v5-tagged MMP-9 with that in control cells containing scrambled siRNA sequences by anti-v5 antibody Western blot analysis. As expected, LH3 down-regulation in MRC-5 cells decreased MMP-9 recruitment (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Depletion of LH3 decreases MMP-9 cell surface recruitment as does the recombinant FN domain, which displaces MMP-9 from the fibroblast membrane. A, LH3 down-regulation in MRC-5 decreases MMP-9 cell surface recruitment. Equal amounts of cell lysates (CL) from control (ctl) and LH3-depleted (KD) MRC-5 incubated with v5-tagged MMP-9 (SN) were loaded onto gels. Recruitment was quantified by densitometry. A representative anti-v5 antibody immunoblot of equal amounts of MRC-5 cell lysates from three independent experiments (lower panel) and the corresponding anti-LH3 antibody immunoblot are shown. B, PLA analysis of WT or LH3-depleted HSF treated with v5-tagged MMP-9. The histogram shows interaction between v5-tagged MMP-9 and endogenous LH3 that is decreased when LH3 is depleted. Lower panels show immunofluorescence images of MMP-9 recruitment (green) to membranes of HSF with an overlap between MMP-9 and LH3 (yellow) that is decreased by LH3 depletion. C, the FN domain prevents MMP-9/LH3 interaction in a dose-dependent manner. PLA analysis of MRC-5 cells treated with MMP-9 only, FN only, or MMP-9 with increased concentrations of the FN domain (1:1, 1:2, and 1:10 corresponding to 1:3.4, 1:6.8, and 1:34 molar ratios). The histogram shows interaction between MMP-9 and endogenous LH3 that decreases as the concentration of FN increases. nb, number. Results represent mean values ±S.E. (error bars). *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

To provide further evidence that the MMP-9/LH3 interaction at the cell surface was indeed impaired by LH3 down-regulation, we used PLA to compare the interaction between MMP-9 and LH3 in control HSF versus HSF depleted of LH3. PLA revealed a significant decrease in the number of events per cell in LH3-depleted compared with control HSF (Fig. 7B, upper panel). Moreover, immunofluorescence analysis illustrates both that MMP-9/LH3 interaction occurs at the cell surface and that formation of the complex is impaired when LH3 is down-regulated (Fig. 7B, lower panel). Thus, MMP-9 recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface is selectively mediated by LH3.

MMP-9 Is Displaced from MRC-5 Cell Surface by Its FN Domain

We next addressed the possible mechanism whereby incubation with the recombinant FN domain inhibits both MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation and α-SMA expression. To do so, we asked whether the FN domain alone might compete with MMP-9 for docking to the fibroblast cell surface and impair MMP-9·LH3 complex formation by displacing MMP-9 from the cell membrane. MRC-5 fibroblasts were incubated with v5-tagged MMP-9 in the presence of increasing concentrations of the FN domain (MMP-9:FN ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:10 or molar ratios of 1:3.4, 1:6.8, and 1:34) after which MMP-9/LH3 interaction was assessed by PLA using mouse anti-MMP-9 antibody, which does not recognize the FN domain, and rabbit anti-LH3 antibody. We observed an increase in the number of fluorescence signals in the cells treated with MMP-9 only compared with cells treated with the FN domain only, confirming that the MMP-9 antibody does not recognize the FN domain (Fig. 7C). Moreover, we noted a strong decrease of the MMP-9/LH3 interaction in the presence of a 3.4 molar excess of FN. Thus, recombinant FN domain prevents LH3-dependent MMP-9 anchoring to the MRC-5 cell surface and provides a mechanism of inhibition of MMP-9-mediated TGF-β activation and fibroblast differentiation.

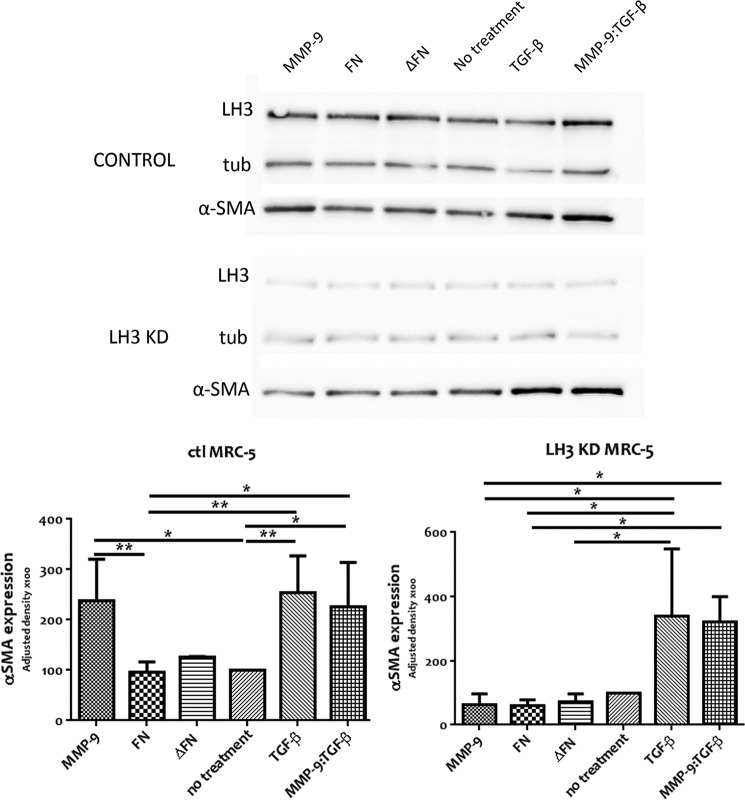

Finally, we assessed α-SMA induction in MRC5 cells depleted of LH3 in response to recombinant MMP-9. Expression of α-SMA in these cells was not enhanced by addition of recombinant MMP-9 to the cell culture medium (Fig. 8). However, induction of α-SMA was rescued by addition of active TGF-β in the presence or absence of MMP-9. These observations support the notion that recruitment by LH3 provides a mechanism for deployment of MMP-9 catalytic activity at the fibroblast cell surface that promotes TGF-β activation and the corresponding enhancement of α-SMA expression.

FIGURE 8.

MMP-9 has no effect in α-SMA induction when LH3 is depleted and can be rescued by active TGF-β. Control (ctl) and LH3-depleted (KD) MRC-5 were incubated for 72 h days with 0.5 μg/ml pro-MMP-9, FN, ΔFN, TGF-β, or pro-MMP-9 with TGF-β (MMP-9:TGF-β). A representative anti-α-SMA antibody immunoblot of equal amounts of control and LH3-depleted MRC-5 cell lysates from three independent experiments (upper panel) is shown. Analysis of α-SMA expression from three independent experiments (lower panel) is shown. Expression quantification was normalized to tubulin (tub). Results represent mean values ±S.E. (error bars). *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

MMP-9 can be recruited to the surface of diverse cell types where it may play an important role in regulating growth factor activation, receptor processing, and pericellular matrix turnover, all of which are highly relevant to tissue remodeling in both physiological and tumor-associated contexts. Thus far, the hyaluronan receptor CD44 has been shown to provide a major docking site for MMP-9 on the surface of a variety of tumor cells and primary keratinocytes (17), although association with other cell surface receptors, including LRP-1, LRP-2, and membrane-anchored glycoprotein RECK, has been reported as well (23–25). The MMP-9 structure responsible for interaction with CD44 resides within the HEX domain (26), leaving open the possibility that other MMP-9 structures may be implicated in cell surface docking to different receptors. We have shown here that MMP-9 can be recruited to the fibroblast cell surface via its fibronectin type II-like motifs by LH3 where it activates latent TGF-β and induces myofibroblast differentiation as reflected by induction of α-SMA expression. LH3-recruited pro-MMP-9 may become activated and remain at the cell surface, cleaving latent TGF-β in the pericellular matrix (as observed in certain tumor cells (17)). Alternatively, pro-MMP-9 may be recruited to the cell surface for proteolytic activation and then released into the ECM to liberate active TGF-β from its latency complex.

Among mammalian MMPs, only MMP-2 and MMP-9 share fibronectin type II-like repeats that form a collagen-binding domain located within the catalytic region in the vicinity of the active site. Fibronectin type II-like motifs are widespread among extracellular proteins and engage in interactions with collagens and gelatin (4, 27). MMP FN type II repeats may have analogous functions, mediating interactions with diverse docking structures and regulating MMP activation and corresponding proteolytic activity. They may thereby provide a means for selective MMP-9 (and possibly MMP-2) targeting in a variety of pathological conditions.

Selective targeting of individual MMPs has been a major hurdle toward therapeutic strategies aimed at blocking MMP-dependent tumor progression as most compounds with potent inhibitory properties are non-selective and tend to block all or nearly all MMP activity with adverse consequences (28, 29). Nevertheless, the continued search for selective means to block single MMPs or subsets thereof has identified potentially promising avenues as illustrated by chemical compounds that target the HEX domain of MMP-9 and that inhibit tumor cell migration and proliferation by abrogating MMP-9 homodimerization (30, 31). An alternative approach may be to target structures that are unique to defined MMPs provided they are shown to play a functionally relevant role in determining MMP localization and activity. The FN domain appears particularly attractive in light of our present observations as, in addition to constituting part of only two MMPs, its delivery in recombinant form may provide selective inhibition of the effect of only this subset of MMPs on fibroblast functions that are highly relevant to tumor progression. Enhanced selectivity of MMP inhibitors has already been achieved by taking advantage of differences in secondary substrate binding sites or exosites within the MMP family (32). Thus, a triple helical peptide that incorporates an FN type II-like motif-binding sequence selectively inhibits MMP-9 type V collagen-specific activity. Similarly, FN type II motif-mediated MMP-9 interaction with LH3 provides a targetable event with potentially beneficial consequences.

Lysyl hydroxylase 3 is a multifunctional protein that localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum but is also secreted into the extracellular space and is associated with collagenous proteins on the cell surface (21). Its principal function resides in lysyl hydroxylase, galactosyltransferase, and glucosyltransferase activities for which sequential deployment is required to generate hydroxylysine and its glycosylated forms (33). More recent studies suggest that deficiency of LH3 glycosyltransferase activity in the extracellular space causes growth arrest, indicating that LH3 glycosyltransferase activity may be important for cell growth and viability (34). Whether these functions may affect MMP-9 activity and vice versa remain to be explored.

The observation that LH3 expressed in a variety of tumor cell types fails to recruit MMP-9 to their cell surface may have several explanations. One possibility is that LH3 undergoes post-translational modifications in fibroblasts but not in tumor cells that enable MMP-9 FN domain recognition. An analogous situation has been observed regarding CD44 recruitment of MMP-9 in selected tumor cells and keratinocytes (18). An alternative possibility is that glycosyltransferase properties of LH3 modify collagenous proteins with which it interacts on the fibroblast cell surface, creating a molecular complex that helps recruit MMP-9. In either case, our observations suggest that at the very least LH3 may provide an important MMP-9 docking mechanism to the fibroblast cell surface that, along with the corresponding cell surface-localized MMP-9 catalytic activity, can be blocked by recombinant FN domain.

Our observation that MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation promotes α-SMA expression in fibroblasts is consistent with a function that supports tumor progression (2, 35). Although the role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor progression is multifaceted as they can inhibit as well as promote malignant growth depending on their activation state and secretion repertoire (36), myofibroblasts are generally believed to support tumor progression by promoting cancer cell survival proliferation and invasiveness. Targeting fibroblasts is thought to be a promising strategy in cancer treatment (37) because they are genetically stable, which reduces the likelihood of drug resistance, and because they are responsible for ECM properties that hamper diffusion of anticancer agents through solid tumors (36). As selective MMP inhibitors are still scarce (28, 29), recombinant FN may provide an attractive reagent for the blockade of a candidate mechanism of MMP-9 activation within the stromal compartment as well as a structural basis for the design of smaller effective MMP-9 inhibitors.

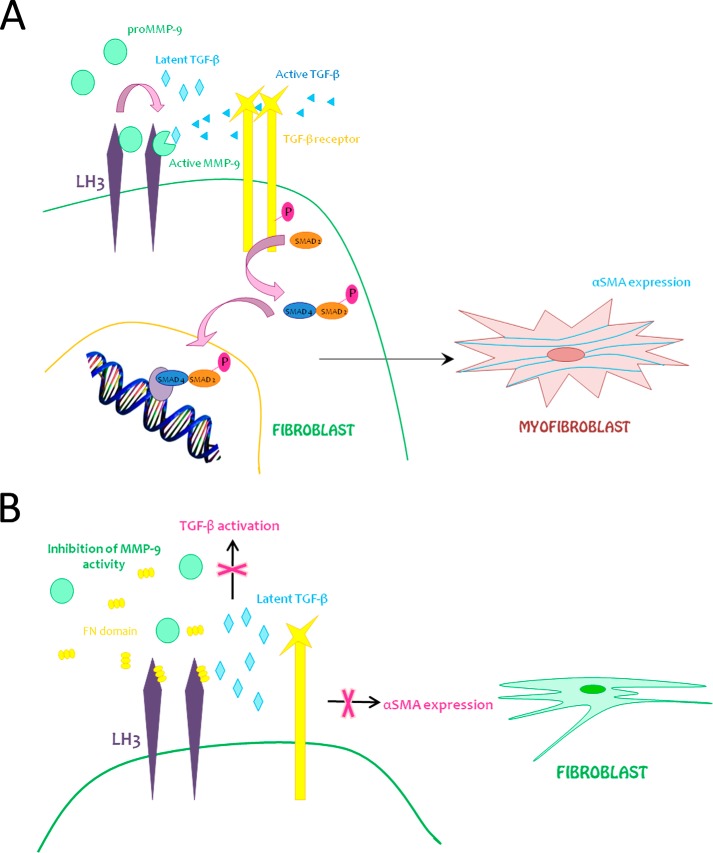

We report a hitherto undiscovered mechanism of MMP-9 recruitment to the surface of fibroblasts. Cell surface activity of MMP-9 has been shown to be important for TGF-β activation whether on the fibroblast surface or in the immediate pericellular fibroblast microenvironment and may play a critical role in fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, providing a mechanism that underlies the constitution of at least a subset of cancer-associated fibroblasts (Fig. 9A). Recombinant FN domain blocks MMP-9-dependent, TGF-β-mediated myofibroblast differentiation and thereby abrogates a potentially important fueling mechanism of tumor progression (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9.

Hypothetical model. A, model 1. Pro-MMP-9 recruitment to the fibroblast cell surface via LH3 activates latent TGF-β and induces α-SMA expression, reflecting myofibroblast differentiation. B, model 2. Recombinant FN domain inhibits both MMP-9-induced TGF-β activation and α-SMA expression in fibroblasts by displacement of MMP-9.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manfredo Quadroni from the Protein Analysis Facility of University of Lausanne for Mass Spectrometry Analysis and all the members of the laboratory for support and helpful discussion. We particularly thank Nils Degrauwe, Giulia Fregni, Carlo Fusco, Marie-Aude Le Bitoux, Patricia Martin, and Anne Planche Roduit for precious help.

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation (FNS) Grant 310030_150024 and a grant from the Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research (ISREC) Foundation.

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- LH3

- lysyl hydroxylase-3

- FN

- fibronectin-like

- α-SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- HEX

- hemopexin-like

- TMLC

- transformed mink lung epithelial cells

- HSF

- human skin fibroblasts

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- PLA

- proximity ligation assay

- PLOD3

- procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3.

References

- 1. Pietras K., Ostman A. (2010) Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1324–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mueller M. M., Fusenig N. E. (2004) Friends or foes—bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhowmick N. A., Neilson E. G., Moses H. L. (2004) Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature 432, 332–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stamenkovic I. (2000) Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion and metastasis. Sem. Cancer Biol. 10, 415–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stamenkovic I. (2003) Extracellular matrix remodelling: the role of matrix metalloproteinases. J. Pathol. 200, 448–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coussens L. M., Tinkle C. L., Hanahan D., Werb Z. (2000) MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell 103, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergers G., Brekken R., McMahon G., Vu T. H., Itoh T., Tamaki K., Tanzawa K., Thorpe P., Itohara S., Werb Z., Hanahan D. (2000) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu X., Chen Z., Wang Y., Yamada Y., Steffensen B. (2005) Functional basis for the overlap in ligand interactions and substrate specificities of matrix metalloproteinases-9 and -2. Biochem. J. 392, 127–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Collier I. E., Krasnov P. A., Strongin A. Y., Birkedal-Hansen H., Goldberg G. I. (1992) Alanine scanning mutagenesis and functional analysis of the fibronectin-like collagen-binding domain from human 92-kDa type IV collagenase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 6776–6781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steffensen B., Wallon U. M., Overall C. M. (1995) Extracellular matrix binding properties of recombinant fibronectin type II-like modules of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. High affinity binding to native type I collagen but not native type IV collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11555–11566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Overall C. M. (2002) Molecular determinants of metalloproteinase substrate specificity: matrix metalloproteinase substrate binding domains, modules, and exosites. Mol. Biotechnol. 22, 51–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roomi M. W., Monterrey J. C., Kalinovsky T., Rath M., Niedzwiecki A. (2009) Patterns of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in human cancer cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 21, 1323–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malla N., Sjøli S., Winberg J. O., Hadler-Olsen E., Uhlin-Hansen L. (2008) Biological and pathobiological functions of gelatinase dimers and complexes. Connect. Tissue Res. 49, 180–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deryugina E. I., Quigley J. P. (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25, 9–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fridman R., Toth M., Chvyrkova I., Meroueh S. O., Mobashery S. (2003) Cell surface association of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B). Cancer Metastasis Rev. 22, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toth M., Chvyrkova I., Bernardo M. M., Hernandez-Barrantes S., Fridman R. (2003) Pro-MMP-9 activation by the MT1-MMP/MMP-2 axis and MMP-3: role of TIMP-2 and plasma membranes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu Q., Stamenkovic I. (1999) Localization of matrix metalloproteinase 9 to the cell surface provides a mechanism for CD44-mediated tumor invasion. Genes Dev. 13, 35–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu Q., Stamenkovic I. (2000) Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-β and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 14, 163–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mira E., Lacalle R. A., Buesa J. M., de Buitrago G. G., Jiménez-Baranda S., Gómez-Moutón C., Martínez-A C., Mañes S. (2004) Secreted MMP9 promotes angiogenesis more efficiently than constitutive active MMP9 bound to the tumor cell surface. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1847–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heikkinen J., Risteli M., Wang C., Latvala J., Rossi M., Valtavaara M., Myllylä R. (2000) Lysyl hydroxylase 3 is a multifunctional protein possessing collagen glucosyltransferase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36158–36163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salo A. M., Wang C., Sipilä L., Sormunen R., Vapola M., Kervinen P., Ruotsalainen H., Heikkinen J., Myllylä R. (2006) Lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3) modifies proteins in the extracellular space, a novel mechanism for matrix remodeling. J. Cell. Physiol. 207, 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abe M., Harpel J. G., Metz C. N., Nunes I., Loskutoff D. J., Rifkin D. B. (1994) An assay for transforming growth factor-β using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter-luciferase construct. Anal. Biochem. 216, 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn-Dantona E., Ruiz J. F., Bornstein P., Strickland D. K. (2001) The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein modulates levels of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) by mediating its cellular catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15498–15503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van den Steen P. E., Van Aelst I., Hvidberg V., Piccard H., Fiten P., Jacobsen C., Moestrup S. K., Fry S., Royle L., Wormald M. R., Wallis R., Rudd P. M., Dwek R. A., Opdenakker G. (2006) The hemopexin and O-glycosylated domains tune gelatinase B/MMP-9 bioavailability via inhibition and binding to cargo receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18626–18637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takahashi C., Sheng Z., Horan T. P., Kitayama H., Maki M., Hitomi K., Kitaura Y., Takai S., Sasahara R. M., Horimoto A., Ikawa Y., Ratzkin B. J., Arakawa T., Noda M. (1998) Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and inhibition of tumor invasion by the membrane-anchored glycoprotein RECK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13221–13226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Redondo-Muñoz J., Ugarte-Berzal E., García-Marco J. A., del Cerro M. H., Van den Steen P. E., Opdenakker G., Terol M. J., García-Pardo A. (2008) α4β1 integrin and 190-kDa CD44v constitute a cell surface docking complex for gelatinase B/MMP-9 in chronic leukemic but not in normal B cells. Blood 112, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Behrendt N. (2004) The urokinase receptor (uPAR) and the uPAR-associated protein (uPARAP/Endo180): membrane proteins engaged in matrix turnover during tissue remodeling. Biol. Chem. 385, 103–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brinckerhoff C. E., Matrisian L. M. (2002) Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coussens L. M., Fingleton B., Matrisian L. M. (2002) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science 295, 2387–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dufour A., Sampson N. S., Li J., Kuscu C., Rizzo R. C., Deleon J. L., Zhi J., Jaber N., Liu E., Zucker S., Cao J. (2011) Small-molecule anticancer compounds selectively target the hemopexin domain of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cancer Res. 71, 4977–4988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dufour A., Zucker S., Sampson N. S., Kuscu C., Cao J. (2010) Role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 dimers in cell migration: design of inhibitory peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35944–35956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lauer-Fields J. L., Whitehead J. K., Li S., Hammer R. P., Brew K., Fields G. B. (2008) Selective modulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) functions via exosite inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20087–20095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Myllylä R., Wang C., Heikkinen J., Juffer A., Lampela O., Risteli M., Ruotsalainen H., Salo A., Sipilä L. (2007) Expanding the lysyl hydroxylase toolbox: new insights into the localization and activities of lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3). J. Cell. Physiol. 212, 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang C., Kovanen V., Raudasoja P., Eskelinen S., Pospiech H., Myllylä R. (2009) The glycosyltransferase activities of lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3) in the extracellular space are important for cell growth and viability. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 508–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kalluri R., Zeisberg M. (2006) Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cirri P., Chiarugi P. (2012) Cancer-associated-fibroblasts and tumour cells: a diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 31, 195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loeffler M., Krüger J. A., Niethammer A. G., Reisfeld R. A. (2006) Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 1955–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]