Background: RNF170 is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane ubiquitin ligase that when mutated at arginine 199 causes a neurodegenerative disease.

Results: The mutation disrupts salt bridges between transmembrane domains, destabilizes the protein, and inhibits Ca2+ signaling via IP3 receptors.

Conclusion: These manifestations of the mutation are likely causative to neurodegeneration.

Significance: Understanding the mechanism of action of mutant ubiquitin ligases will lead to better therapies.

Keywords: calcium intracellular release, E3 ubiquitin ligase, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), inositol trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R), neurodegenerative disease, RNF170

Abstract

RNF170 is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane ubiquitin ligase that contributes to the ubiquitination of activated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors, and also, when point mutated (arginine to cysteine at position 199), causes autosomal dominant sensory ataxia (ADSA), a disease characterized by neurodegeneration in the posterior columns of the spinal cord. Here we demonstrate that this point mutation inhibits RNF170 expression and signaling via IP3 receptors. Inhibited expression of mutant RNF170 was seen in cells expressing exogenous RNF170 constructs and in ADSA lymphoblasts, and appears to result from enhanced RNF170 autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. The basis for these effects was probed via additional point mutations, revealing that ionic interactions between charged residues in the transmembrane domains of RNF170 are required for protein stability. In ADSA lymphoblasts, platelet-activating factor-induced Ca2+ mobilization was significantly impaired, whereas neither Ca2+ store content, IP3 receptor levels, nor IP3 production were altered, indicative of a functional defect at the IP3 receptor locus, which may be the cause of neurodegeneration. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic deletion of RNF170 showed that RNF170 mediates the addition of all of the ubiquitin conjugates known to become attached to activated IP3 receptors (monoubiquitin and Lys48- and Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains), and that wild-type and mutant RNF170 have apparently identical ubiquitin ligase activities toward IP3 receptors. Thus, the Ca2+ mobilization defect seen in ADSA lymphoblasts is apparently not due to aberrant IP3 receptor ubiquitination. Rather, the defect likely reflects abnormal ubiquitination of other substrates, or adaptation to the chronic reduction in RNF170 levels.

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, ubiquitin ligases (E3)2 work together with ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2) to promote ubiquitination of a range of substrates, often leading to their degradation by the proteasome (1–5). Mammals express hundreds of E3s, the vast majority of which contain a RING domain, a motif that appears to provide a docking site for E2s and be necessary for ubiquitin transfer to the substrate (3–5). Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) is the term used to describe the pathway by which aberrant ER lumen or membrane proteins are removed from the cell via ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (6, 7). A recent bioinformatic survey of RING domain-containing proteins that localize to the ER membrane and that could play a role in ERAD identified a group of 24 E3s (8), some of which (e.g. HRD1) appear be capable of mediating the ubiquitination of a broad array of substrates, whereas others (e.g. TRC8) have a much narrower substrate range (3, 6, 7). Furthermore, several of the E3s identified (e.g. RNF170) have yet to be fully characterized (8).

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are ER membrane proteins that form tetrameric Ca2+ channels that govern ER Ca2+ store release (9, 10). When persistently activated, a portion of cellular IP3Rs are ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome apparently via the ERAD pathway, and this IP3R “down-regulation” suppresses Ca2+ mobilization (11, 12). Recent studies on the mechanism of IP3R processing by the ERAD pathway have shown that a complex composed of the integral ER membrane proteins erlin1 and erlin2 associates rapidly with activated IP3Rs (11–14), as does RNF170 (15). RNF170 is ∼257 amino acids in length, is highly conserved in mammals, is predicted to have 3 transmembrane (TM) domains, with the RING domain facing the cytosol (15, 16), and is constitutively associated with the erlin1/2 complex. RNF170 contributes to IP3R ubiquitination (15), although whether it is responsible for the addition of all of the conjugates that become attached to activated IP3Rs (monoubiquitin and Lys48- and Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains) (17, 18) is currently unknown. Remarkably, a recent molecular genetic study demonstrated that autosomal dominant sensory ataxia (ADSA), a rare neurodegenerative disease characterized by ataxic gait, reduced sensory perception, and neurodegeneration in the posterior columns of the spinal cord, segregates with an arginine (Arg199) to cysteine mutation in human RNF170 (16, 19). Here we examine the effects of this mutation on the properties of RNF170 and find that it destabilizes the protein because of disruption of a salt bridge between TM domains 2 and 3, and that mutant RNF170 disrupts Ca2+ signaling at the IP3R locus in ADSA lymphoblasts. Genetic deletion of RNF170 revealed that RNF170 mediates the addition of all ubiquitin conjugates to activated IP3Rs and that the ubiquitin ligase activities of wild-type and mutant RNF170 toward activated IP3Rs are apparently identical. Thus, aberrant ubiquitination of other substrates, or cellular adaptation to chronically reduced RNF170 levels likely accounts for the ADSA-associated Ca2+ signaling deficit.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

HeLa cells were cultured as described (13). Human lymphoblast cell lines were isolated from control and affected individuals (16) and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml of penicillin, 50 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 1 mm l-glutamine. Lymphoblasts were cultured in flasks, fed every 2–3 days, and subcultured 1:10 once per week. Lipofectamine was from Invitrogen, anti-FLAG epitope clone M2 was from Sigma, anti-HA epitope clone HA11 was from Covance, anti-ubiquitin clone FK2 and MG-132 were from BioMol International, anti-RNF170, anti-erlin1, anti-erlin2, anti-Hrd1, anti-gp78, anti-IP3R1, and anti-IP3R2 were prepared as described (13–15, 20), anti-β-tubulin was from Cell Signaling Technology, anti-p97 was from Research Diagnostics Inc., anti-p53 clone DO-1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, anti-IP3R3 was from BD Biosciences, anti-Lys48 and anti-Lys63 linkage-specific antibodies were a generous gift from Genentech, anti-IP3R1–3, which recognizes all IP3R types equally well (21), was a generous gift from Dr. Jan Parys (KU Leuven, Belgium), endoglycosidase H (endo H) was from New England Biolabs, and fura2-AM, cycloheximide, platelet-activating factor (PAF), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) were from Sigma.

Plasmids

Mouse and human RNF170 cDNAs were cloned from mouse αT3 cells and human lymphoblasts as described (15). RNF170FLAG was constructed by ligating the sequence encoding the 257-amino acid mouse RNF170 into the KpnI and BamHI sites of the pCMV14–3xFLAG expression vector such that a triple FLAG tag (DYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDKG) is spliced to the C terminus (15). RNF170HA was constructed by PCR amplification of mouse and human RNF170 cDNAs, such that an HA tag (GYPYDVPDYAG) is spliced to the C terminus. Additional constructs were created via PCR that encode proteins with an optimal N-glycosylation consensus sequence (NSTMMS) (22) immediately after the HA tag, and with a variety of amino acid substitutions. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Expression and Analysis of RNF170 Constructs

To analyze the expression of exogenous RNF170 and its mutants, HeLa cells (750,000/well of a 6-well plate) were transfected (7 μl of Lipofectamine plus 4.8 μg of total DNA), and 24–48 h later cells were collected with 155 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4. Cells were then centrifuged (2,300 × g for 1 min), disrupted for 30 min at 4 °C with lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 μm pepstatin, 0.2 mm PMSF, 0.2 μm soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 8.0), centrifuged (16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), and supernatant samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described (13–15). For studying the interaction between the erlin1/2 complex and RNF170 by co-immunoprecipitation (15), cells were disrupted using lysis buffer that contained 1% CHAPS instead of Triton X-100. The ubiquitin ligase activity of immunopurified RNF170FLAG constructs was assessed as described (15).

Lymphoblasts

To assess protein expression in cell lysates, lymphoblasts were collected by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 5 min), washed once by resuspension in PBS followed by centrifugation (16,000 × g for 1 min), disrupted for 30 min at 4 °C with 1% CHAPS lysis buffer, centrifuged (16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), and supernatant samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described (13–15). For measurement of the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c), lymphoblasts were collected by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 1 min), washed once, and then incubated in culture medium at 2 mg of protein/ml with 5 μm fura2-AM for 1 h at 37 °C, washed 4 times with Krebs HEPES buffer (23), and finally resuspended at 0.5 mg of protein/ml in Krebs HEPES buffer for measurement of [Ca2+]c at 37 °C, as described (23). For measurement of IP3 levels, lymphoblasts were collected by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 5 min), washed once by resuspension in RPMI 1640 (Cellgro) followed by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 5 min), resuspended in RPMI 1640 and preincubated at 37 °C for 1 h, then exposed to vehicle (DMSO) or PAF, and IP3 mass was measured as described (23).

Generation and Analysis of RNF170 Knock-out and Reconstituted Cell Lines

The CRISPR/Cas9 system (24, 25) was used to target an exon within the mouse RNF170 gene that was common to all predicted splice variants (exon 6). Oligonucleotides that contained the RNF170 target CRISPR sequence (GATACTGGCGATACGGGTCCTGG) were annealed and then ligated into AflII-linearized gRNA vector (Addgene). αT3 mouse pituitary cells were transfected (18) with a mixture of the gRNA construct and vectors encoding Cas9 (Addgene) and EGFP (Clontech). Two days post-transfection, EGFP-expressing cells were selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and plated at ∼1 cell/well in 96-well plates. Colonies were expanded and screened for ablation of RNF170 expression by immunoblotting with anti-RNF170 (raised against amino acids 50–65 of RNF170) (15). Of the cell lines screened, ∼30% lacked RNF170 and 2 of those were expanded for characterization of IP3R1 processing with essentially identical results; clone IC8 was used for the experiments shown in Fig. 7. Reconstituted cell lines were obtained by transfecting clone IC8 with cDNAs encoding mouse RNF170 and R198CRNF170 (18), followed by selection in 1.3 mg/ml of G418 for 72 h, plating at ∼1 cell/well in 96-well plates, colony expansion, screening with anti-RNF170, and maintenance in 0.3 mg/ml of G418. 2 clones expressing each construct were characterized with essentially identical results.

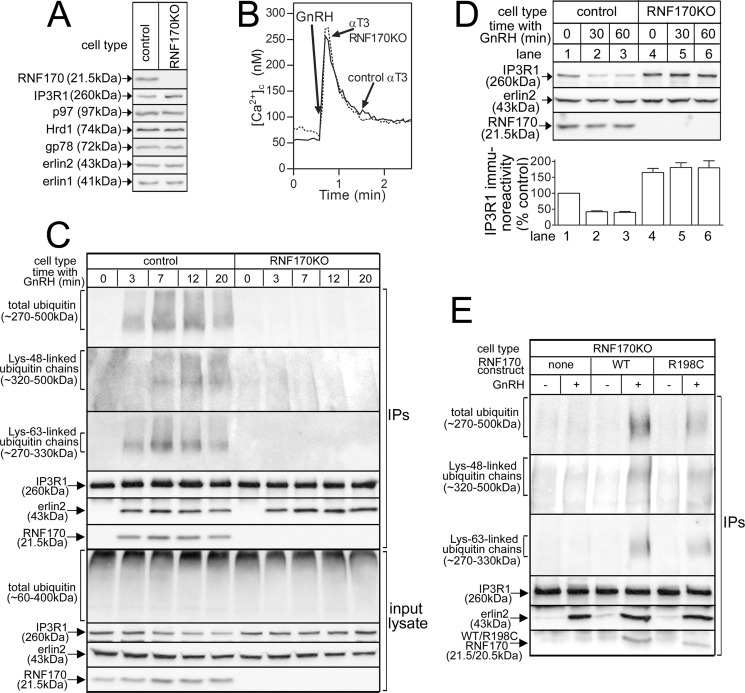

FIGURE 7.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of RNF170 and reconstitution with exogenous RNF170 constructs. A, levels of RNF170, IP3R1, and other pertinent proteins in lysates from αT3 control and RNF170KO cells. B, GnRH (0.1 μm)-induced Ca2+ mobilization in αT3 control and RNF170KO cells. C, IP3R1 ubiquitination in αT3 control and RNF170KO cells. Cells were incubated with 0.1 μm GnRH and anti-IP3R1 IPs and input lysates were probed for the proteins indicated. D, IP3R1 down-regulation in αT3 control and RNF170KO cells. Cells were incubated with 0.1 μm GnRH and lysates were probed for the proteins indicated. The histogram shows combined quantitated immunoreactivity (mean ± S.E., n = 4). E, reconstitution of IP3R1 ubiquitination in RNF170KO cells. αT3 RNF170KO cells stably expressing WTRNF170 or R198CRNF170 were incubated without or with 0.1 μm GnRH for 20 min, and anti-IP3R1 IPs were probed for the proteins indicated.

For analysis of IP3R1 ubiquitination and protein levels, cells were incubated with 1% CHAPS lysis buffer lacking dithiothreitol, but supplemented with 5 mm N-ethylmaleimide, for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by addition of 5 mm dithiothreitol and centrifugation (16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C). Lysates were then incubated with anti-IP3R1 to immunoprecipitate IP3R1 as described (15) and complexes were heated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to SDS-PAGE in 5% gels for ubiquitin conjugate analysis, or 100 °C for 5 min prior to SDS-PAGE in 10% gels for analysis of other proteins. [Ca2+]c was measured as described (23).

Data Presentation

All experiments were repeated at least once, and representative images of gels or traces are shown. Immunoreactivity was detected and quantitated using Pierce ECL reagents and a GeneGnome Imager (Syngene Bio Imaging). Quantitated data are expressed as mean ± S.E. or range of n independent experiments.

Results

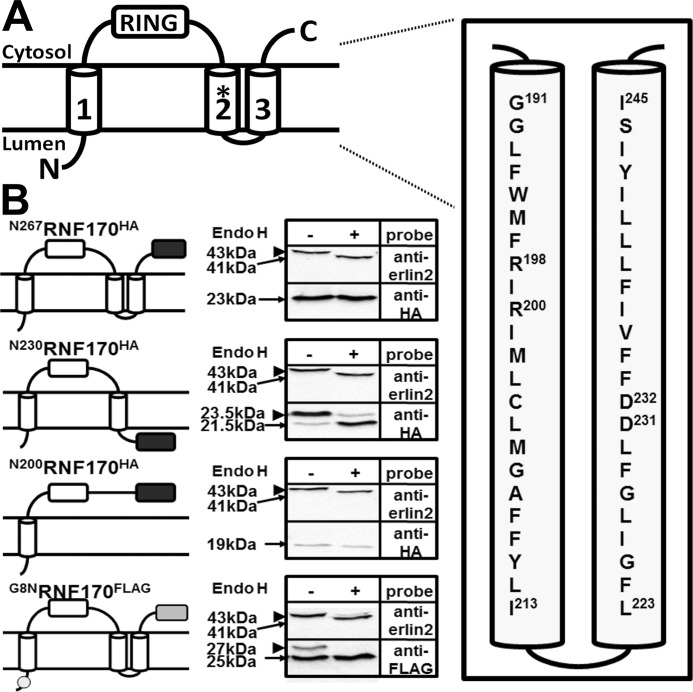

Analysis of the Membrane Topology of RNF170

The predicted topology of mouse RNF170, derived from bioinformatic analysis, together with the amino acid sequences of TM domains 2 and 3 are depicted in Fig. 1A. The sequence of human RNF170 is very similar to that of mouse RNF170 (91% identical) and human RNF170 has the same predicted topology (15, 16). Note that Arg199 in the human sequence corresponds to Arg198 in the mouse sequence, because of the absence of Asp16 from the latter (15, 16). The existence of TM domains 2 and 3 was confirmed experimentally, using a series of truncation mutants containing a C-terminal HA/glycosylation tag that together with an assessment of sensitivity to the deglycosylating activity of endo H, can provide information on orientation across the ER membrane (22, 26) (Fig. 1B). That full-length RNF170 (N267RNF170HA) is insensitive to endo H (and is therefore not glycosylated) localizes the C terminus of this construct to the cytosol (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the sensitivity of N230RNF170HA to endo H shows that the C terminus of this construct is glycosylated and is within the ER lumen, demonstrating that TM2 traverses the ER membrane (Fig. 1B). Following the same logic, that N200RNF170HA is insensitive to endo H and is not glycosylated localizes the C terminus of this construct to the cytosol and confirms the orientation of TM2 (Fig. 1B). Finally, to confirm the location of the N terminus, G8NRNF170FLAG was created, which due to replacement of Gly8 with asparagine, contains an N-glycosylation consensus sequence (NQS) (22, 26) very near the N terminus. This construct was partially glycosylated, indicating that the N terminus is located in the ER lumen (Fig. 1B); that the glycosylation was relatively weak may be because the consensus sequence is suboptimal in comparison to the optimal sequence (NSTMMS) present in the other constructs (22). Overall, these data are consistent with the topology of TM domains 1, 2, and 3 shown in Fig. 1A.

FIGURE 1.

Membrane topology of RNF170. A, predicted topology of RNF170 (15) with the TM2/3 region expanded to show the mouse amino acid sequence. Note that the amino acid that corresponds to Arg199 of human RNF170 is Arg198 in mouse RNF170, and that the sequences of human and mouse TM2/3 regions are identical, with the exception that Met202 of mouse RNF170 is Ile203 in human RNF170 (15, 16). The RING domain, the three TM domain regions, and the N and C termini are indicated, and Arg198 is identified with an asterisk. The precise limits of the predicted TM domains have not been defined experimentally, but the scheme shown is predicted by multiple programs (e.g. TMHMM, TOPCONS, etc). B, N-glycosylation of RNF170 mutants. An HA/glycosylation tag (black box) was introduced at the C terminus of full-length RNF170 (N267RNF170HA), or truncated RNF170 lacking putative TM domain 3 (N230RNF170HA), or putative TM domains 2 and 3 (N200RNF170HA). These, and G8NRNF170FLAG (FLAG tag indicated by a gray box and the G8N mutation with a circle) were expressed in HeLa cells, lysates were incubated without or with 1 unit/μl of endo H for 3 h at 37 °C, and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Blots were then probed with anti-HA or anti-FLAG to identify the exogenous RNF170 constructs, or anti-erlin2 to identify endogenous erlin2, which is known to be N-glycosylated (13, 14), and which serves as a positive control for endo H. The migration positions of unmodified and N-glycosylated species are indicated with arrows and arrowheads, respectively; degylcosylation of erlin2, N230RNF170HA, and G8NRNF170FLAG by endo H reduces their apparent molecular masses by ∼2 kDa.

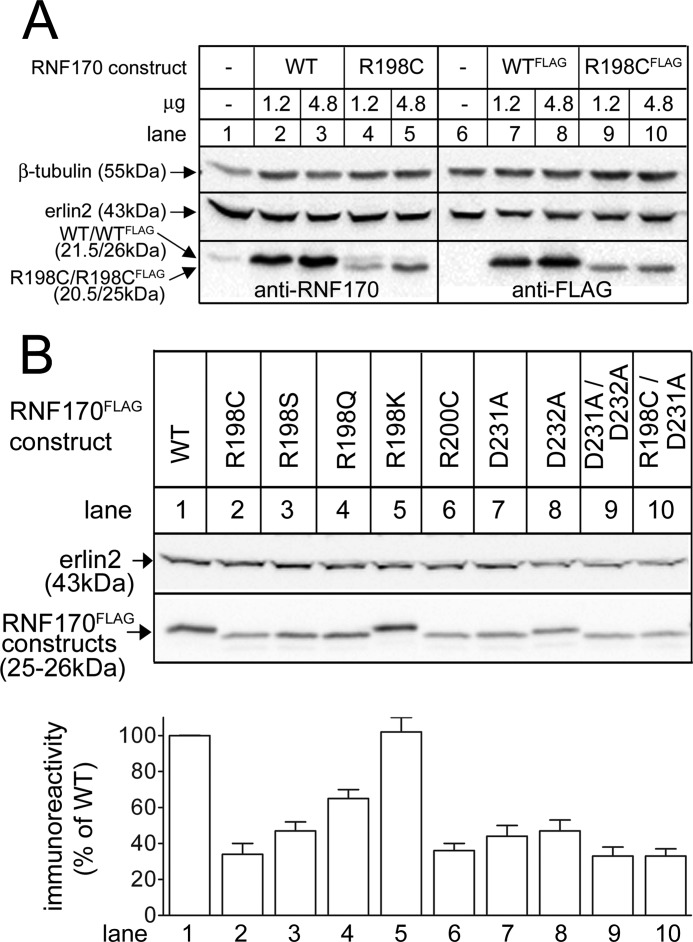

Effects of the Arg198 to Cys mutation on RNF170

Remarkably, the Arg198 to Cys mutation significantly reduced RNF170 expression. This was seen when the mutation was introduced into either untagged RNF170 or RNF170FLAG (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the mutants migrated ∼1 kDa more rapidly than their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2A). Additional mutants were made to explore the basis for the reduction in expression and the migration shift, using RNF170FLAG as a template (Fig. 2B). To examine the possibility that these changes resulted from disulfide bond formation with the newly introduced cysteine, Arg198 was replaced with serine, which is similar in size to cysteine, but which cannot form disulfide bonds. However, R198SRNF170FLAG was also expressed poorly and migrated rapidly (Fig. 2B, lane 3), ruling out a role for disulfide bonds. Likewise, to examine whether the changes were due to loss of the bulky side chain of arginine, or the positive charge, Arg198 was replaced with glutamine, which is relatively bulky, but is uncharged, albeit polar. R198QRNF170FLAG was also expressed quite poorly and migrated rapidly (lane 4), suggesting that it is not the bulk of arginine, but rather its positive charge, that is necessary for normal expression and migration. This was confirmed by replacing Arg198 with lysine, which has a slightly shorter side chain, but is still positively charged; R198KRNF170FLAG was expressed and migrated similarly to WTRNF170FLAG (lane 5).

FIGURE 2.

Effects of mutation of Arg198 and other amino acids on RNF170 expression. cDNAs encoding wild-type (WT) and mutant RNF170 constructs and vector alone were transfected into HeLa cells and cell lysates were probed as indicated. Erlin2 and β-tubulin served as loading controls. A, lysates were probed with anti-RNF170, which detects both endogenous and exogenous untagged RNF170 constructs (lanes 1–5), or with anti-FLAG, which detects just exogenous FLAG-tagged constructs (lanes 6–10). B, lysates were probed with anti-FLAG and the histogram shows combined quantitated immunoreactivity (mean ± S.E., n ≥ 3).

Examination of the amino acid sequences of TM domains 2 and 3 (Fig. 1A) revealed the presence of an additional arginine in TM2 (Arg200) and two aspartic acids in TM3 (Asp231 and Asp232) (Fig. 1A), suggesting that ionic interactions between TM2 and TM3 could be required for wild-type behavior. Mutation of these amino acids confirmed this notion, as R200CRNF170FLAG, D231ARNF170FLAG, D232ARNF170FLAG, and D231A/D232ARNF170FLAG all expressed poorly and migrated more rapidly than RNF170FLAG (lanes 6–9). Thus, ionic interactions between arginines in TM2 and aspartic acids in TM3 appear to be required for normal expression of RNF170. Furthermore, it appears that 2 charged amino acids in each TM are required for normal expression, because mutation of one arginine and one aspartic acid in R198C/D231ARNF170FLAG did not rescue expression (lane 10). Finally, it is noteworthy that accelerated migration correlated well with reduced expression (Fig. 2B) and was caused by both arginine and aspartic acid loss and is therefore not due to a change in net protein charge. Rather, these data, together with the fact that RNF170 migrates at 21.5 kDa rather than the predicted 30 kDa (15), suggest that RNF170 is not fully denatured during SDS-PAGE and that the mutations affect the structural organization that is retained. The mutations may also alter the structure of RNF170 in vivo, which in turn, could account for the reductions in expression, perhaps because of protein destabilization.

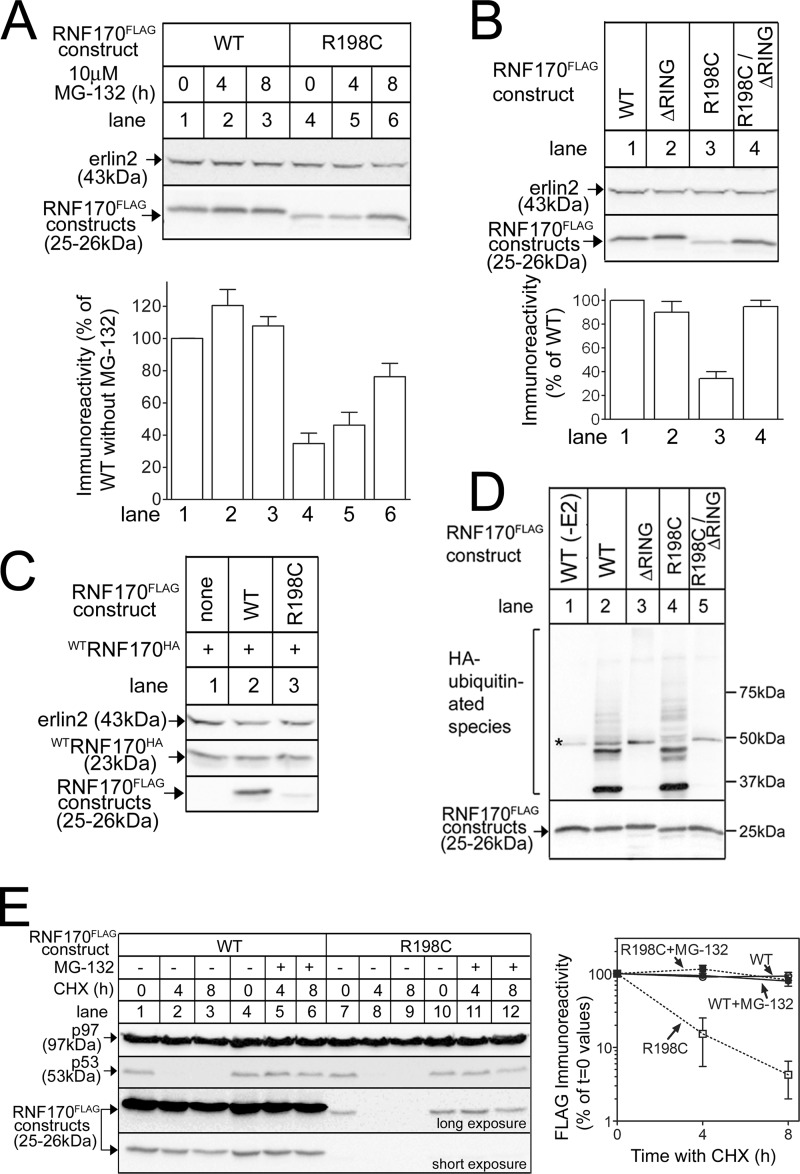

Mechanism of Reduced Expression

To explore possible destabilization mechanisms, we examined the effects of the proteasome inhibitor MG-132. When incubated with cells expressing exogenous RNF170FLAG constructs (Fig. 3A), MG-132 caused a marked accumulation of R198CRNF170FLAG (lanes 4–6), although leaving WTRNF170FLAG levels essentially unaltered (lanes 1–3). Thus, the proteasome appears to mediate the reduced expression of R198CRNF170FLAG. Furthermore, as E3 autoubiquitination is a commonly observed phenomenon (27), we examined the effects of inactivating ligase activity on R198CRNF170FLAG expression. Previously, we have shown that mutation of Cys101 and His103 in the RING domain of mouse RNF170 blocks ubiquitin ligase activity (15), and introduction of these mutations into R198CRNF170FLAG (creating R198C/ΔRINGRNF170FLAG) normalized expression (Fig. 3B, lane 4), suggesting that ligase activity, and most likely autoubiquitination, mediates the reduced expression of R198CRNF170FLAG. Interestingly, the R198C/ΔRINGRNF170FLAG mutant still migrated faster than WTRNF170FLAG, suggesting that the putative structural change has not been reversed by mutation of the RING domain (Fig. 3B, lane 4). A role for autoubiquitination was supported by the observation that WTRNF170HA expression was not differentially affected by co-expression of WTRNF170FLAG and R198CRNF170FLAG (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 and 3); this result shows that the apparent destabilizing effect of the R198C mutation is intramolecular and is not transmitted to co-expressed WTRNF170HA molecules. Importantly, R198CRNF170FLAG exhibited in vitro ubiquitin ligase activity similar to that of WTRNF170FLAG (Fig. 3D, lanes 2 and 4), indicating that it is fully capable of autoubiquitinating. Finally, to determine protein half-lives, transfected cells were incubated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 3E). This revealed that the half-life of R198CRNF170FLAG is much shorter than that of WTRNF170FLAG, and that MG-132 blocks R198CRNF170FLAG degradation. Overall, these data indicate that the R198C mutation decreases RNF170 expression by triggering the molecule to autoubiquitinate and then be degraded by the proteasome.

FIGURE 3.

The R198C mutation reduces RNF170 expression via autoubiquitination and the proteasome. A-C, cDNAs encoding tagged WT and mutant RNF170 constructs transfected into HeLa cells were treated as indicated, and cell lysates were probed with anti-FLAG or anti-HA to recognize exogenous RNF170 constructs, or anti-erlin2, which served a loading control. The histograms show combined quantitated immunoreactivity (mean ± S.E., n ≥ 4). D, RNF170FLAG constructs were immunopurified from transfected HeLa cells and incubated with E1 (UBE1), E2 (UbcH5b), and HA-ubiquitin as indicated for 30 min at 30 °C, with the exception of lane 1, which lacked E2. Samples were then probed with anti-HA to assess ubiquitination (upper panel), or anti-FLAG to assess the levels of RNF170FLAG constructs (lower panel). The asterisk marks a background band. E, transfected HeLa cells were treated as indicated with 20 μg/ml of cycloheximide (CHX), without or with 10 μm MG-132. Cell lysates were then probed with anti-p53 as a positive control for cycloheximide action, anti-p97 as a loading control, and anti-FLAG to recognize exogenous RNF170 constructs (long and short exposures are shown to facilitate visualization of immunoreactivity changes). The graph shows combined quantitated FLAG immunoreactivity, using the long exposure for R198CRNF170FLAG and the short exposure for WTRNF170FLAG (mean ± range, n = 2).

The R198C Mutation Does Not Alter Membrane Topology, Subcellular Localization, or Interaction with the Erlin1/2 Complex

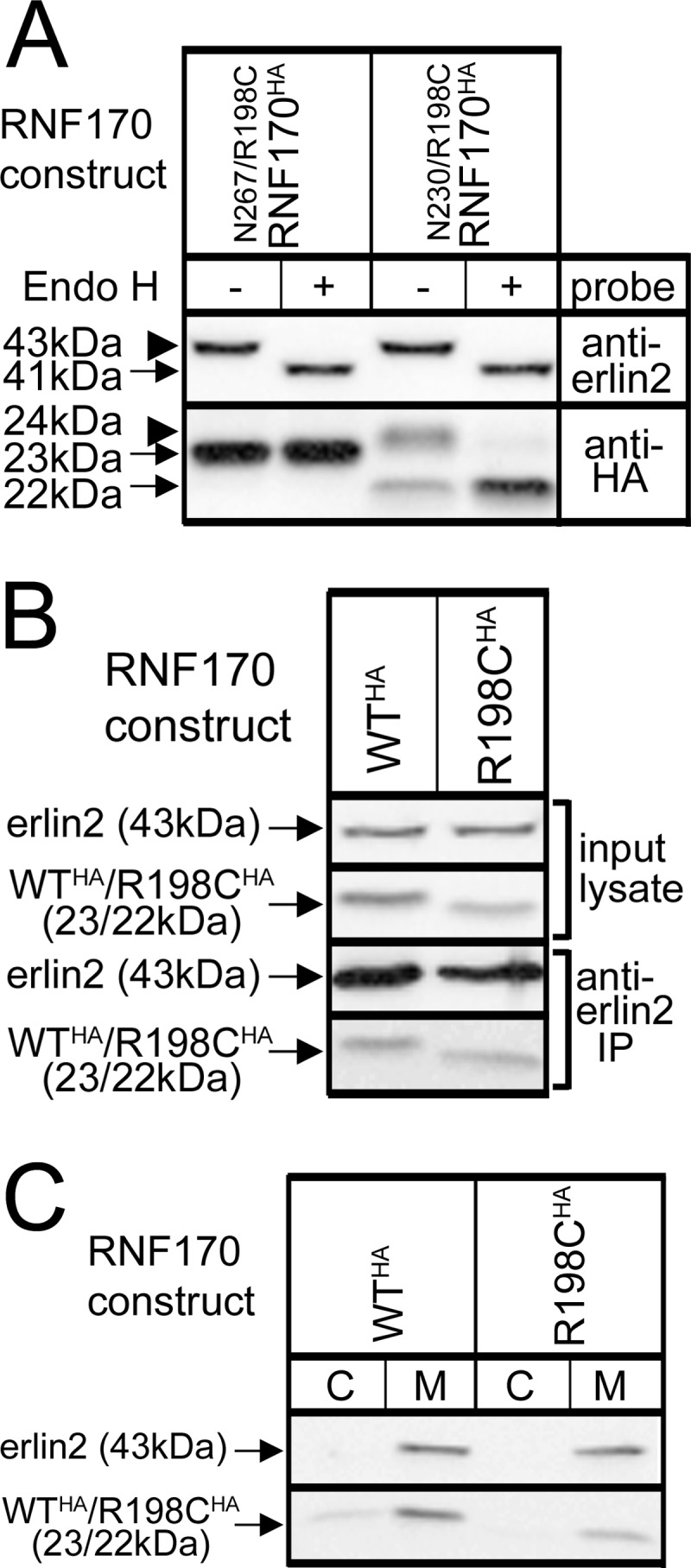

To explore why mutation-induced salt bridge disruption triggers RNF170 autoubiquitination, we first examined whether subcellular localization was altered. However, the extent of N-glycosylation seen for the relevant constructs shown in Fig. 1B (N267RNF170HA and N230RNF170HA) was not substantially altered by introduction of the R198C mutation (Fig. 4A), indicating that localization to the ER and insertion of TM domains is normal. Likewise, interaction with the endogenous erlin1/2 complex was normal, because immunoprecipitation with anti-erlin2 (15) recovered WTRNF170HA and R198CRNF170HA equally well (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, membrane association was normal, as both WTRNF170HA and R198CRNF170HA were fractionated with membranes (Fig. 4C). Thus, the R198C mutation does not dramatically alter the localization of RNF170, indicating that a subtle change in its properties (e.g. in the way that it folds) accounts for its apparent autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.

FIGURE 4.

Lack of effect of the R198C mutation on RNF170 membrane association and topology, and interaction with the erlin1/2 complex. cDNAs encoding HA-tagged WT and mutant RNF170 constructs were transfected into HeLa cells. A, N-glycosylation of N267/R198CRNF170HA and N230/R198CRNF170HA, R198C-containing versions of the constructs shown in Fig. 1B, was assessed as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. B, interaction with the erlin1/2 complex. Erlin1/2 complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-erlin2 was probed for RNF170 constructs (lower panels). Note that the amounts of WTRNF170HA and R198CRNF170HA that co-immunoprecipitate are proportional to the amounts in input lysates, indicating that they interact with the erlin1/2 complex equally well. C, cells were lysed and centrifuged into cytosol (C) and membrane (M) factions as described (13), and probed as indicated.

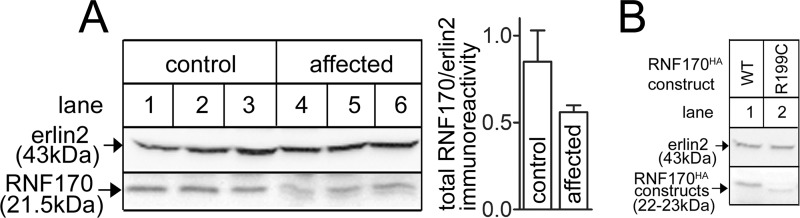

RNF170 Expression in Control and ADSA-affected Individuals

Lymphoblast lines from control and ADSA-affected individuals were examined for RNF170 expression (Fig. 5A). In controls, an anti-RNF170 immunoreactive band at ∼21.5 kDa was observed (lanes 1–3), the same size as endogenous HeLa cell RNF170 and untagged mouse RNF170 (Fig. 2A). Remarkably, in affected lymphoblasts the strength of the 21.5-kDa band was reduced and an additional weaker band at ∼20.5 kDa was also observed (lanes 4–6). These results are consistent with the expression level and migration differences seen between exogenous mouse WTRNF170 and R198CRNF170 (Fig. 2A) and between exogenous human WTRNF170 and R199CRNF170 (Fig. 5B), and with the knowledge that affected individuals are heterozygote (16). Thus, it appears that the R199CRNF170 encoded by the mutant allele in affected individuals migrates at ∼20.5 kDa and is relatively poorly expressed. This leads to an ∼27% reduction in total RNF170 immunoreactivity in affected lymphoblasts (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

RNF170 levels in lymphoblasts from control and ADSA-affected individuals. A, lysates from 3 control (lanes 1–3) and 3 affected individuals (lanes 4–6) were probed with anti-RNF170 and anti-erlin2. For the panels shown, immunoreactivity was quantitated and is plotted as total RNF170/erlin2 immunoreactivity (arbitrary units). Multiple quantitations of total RNF170 immunoreactivity from these and other lymphoblast lines showed that affected individuals contained 73 ± 5% of the immunoreactivity seen in control lymphoblasts (n ≥ 5). B, cDNAs encoding human WTRNF170HA and R199CRNF170HA were transfected into HeLa cells and cell lysates were probed as indicated. Erlin2 served as a loading control.

Ca2+ Mobilization via IP3 Receptors Is Impaired in Affected Lymphoblasts

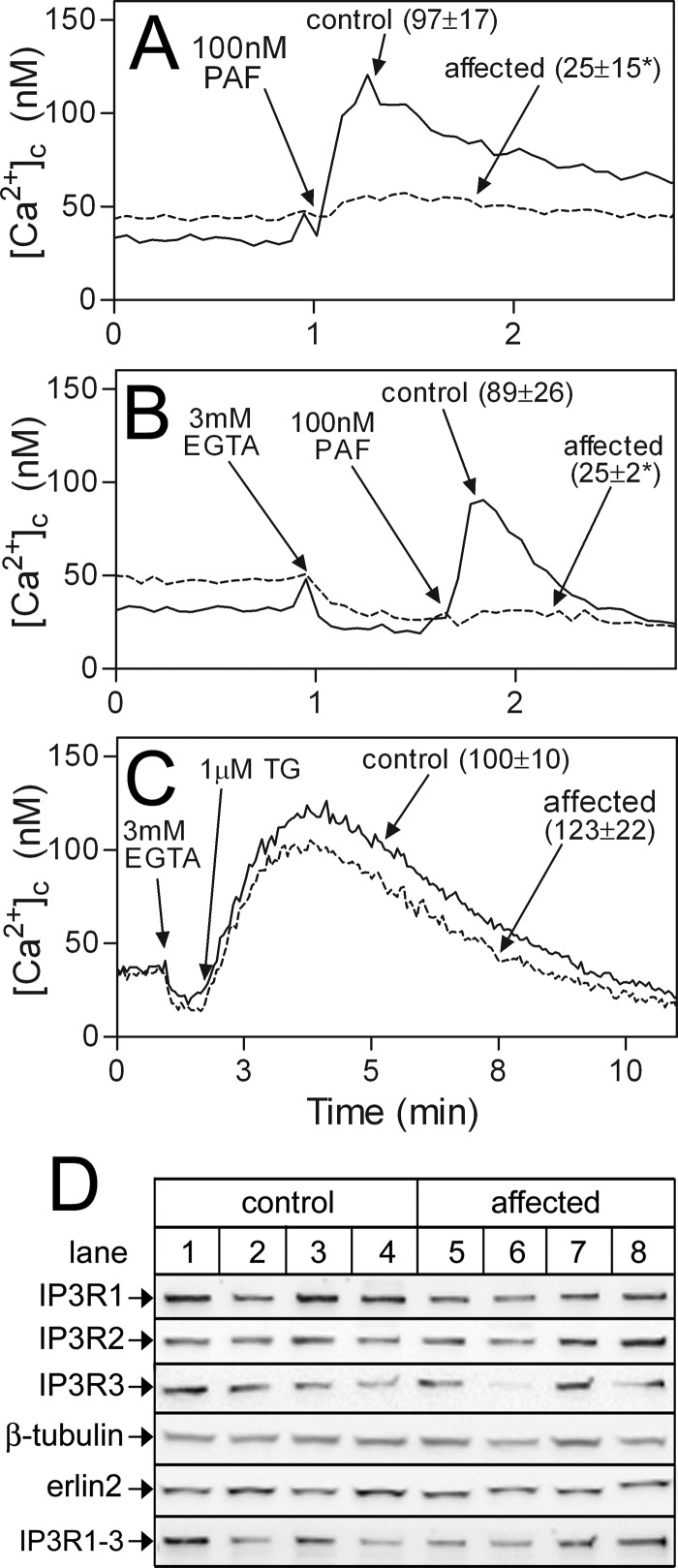

Because IP3Rs are the only known substrates for RNF170 (15), we examined whether IP3R function was different in control and affected lymphoblasts, using PAF to trigger IP3R-mediated Ca2+ mobilization (28) (Fig. 6). Remarkably, PAF-induced increases in [Ca2+]c were significantly suppressed in affected lymphoblasts (Fig. 6A), suggesting that IP3R-mediated Ca2+ mobilization might be impaired, although the suppression could also be due to an effect on Ca2+ entry (29). To rule out any role for Ca2+ entry, EGTA was added immediately prior to PAF to chelate extracellular Ca2+ to ∼100 nm (23), and under these conditions the suppression of PAF-induced increases in [Ca2+]c was still clearly evident (Fig. 6B). To examine if the suppression results from ER Ca2+ stores being smaller, cells were exposed to the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-APTase pump inhibitor thapsigargin, which allows Ca2+ leak from the ER in an IP3R-independent manner (30). However, thapsigargin caused the same [Ca2+]c increase in control and affected lymphoblasts (Fig. 6C), indicating that Ca2+ stores are of equal size. Likewise, reduced IP3 formation was not the reason for the suppression, as PAF-induced increases in IP3 mass were the same in control and affected lymphoblasts (increases over basal resulting from 0.5 min exposure to 100 nm PAF were 24 ± 8 and 35 ± 15%, respectively; n = 3). Finally, measurement of the levels of IP3R1–3 did not reveal any consistent differences between control and affected lymphoblasts (Fig. 6D). Overall, these data indicate that Ca2+ mobilization via IP3Rs is impaired in affected lymphoblasts, but not because of a change in Ca2+ store size, or the abundance of IP3Rs, and point toward a mechanism that involves a regulation of IP3R activity.

FIGURE 6.

Assessment of the IP3-medited Ca2+ signaling pathway in lymphoblasts. Multiple control and affected lymphoblast cell lines (n) were analyzed. A–C, fura2-loaded cells were exposed to PAF, EGTA, and thapsigargin (TG) as indicated and [Ca2+]c was calculated. Values in parentheses are mean ± S.E. of PAF- or TG-induced increases in [Ca2+]c over basal values (n ≥ 4, with * indicating p < 0.05 when comparing values from control versus affected cells). D, lysates from 4 control and 4 affected lymphoblast lines were probed for the proteins indicated. Total IP3R immunoreactivity in control and affected lymphoblasts, measured with anti-IP3R1–3 (lowest panel), was 80 ± 20 and 76 ± 15 arbitrary units, respectively (mean ± S.E.).

Ubiquitin Ligase Activity of RNF170 and R198CRNF170 in Cells

R198CRNF170 exhibits apparently normal ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro when mixed with purified enzymes (Fig. 3D), but that tells us almost nothing about how its activity might differ from that of WTRNF170 in vivo, where the intracellular milieu contains a full complement of E2s, substrates, and other factors. To date, endogenous activated IP3Rs are the only known substrates for RNF170 (15), but it has yet to be resolved whether RNF170 is responsible for the addition of all of the ubiquitin conjugates that become attached to activated IP3Rs, or just some (17, 18). Initially, we sought to compare the ligase activities of WTRNF170 and R199CRNF170 toward IP3Rs in control and ADSA lymphoblasts, but pilot experiments showed that to be unfeasible, primarily because of the paucity of IP3Rs therein (data not shown). Thus, we employed αT3 cells, the cells in which we first identified RNF170 (15) and that exhibit very robust IP3R1 ubiquitination in response to the IP3 generating cell surface receptor agonist GnRH (17, 18). First, to determine which ubiquitin conjugates RNF170 adds, we deleted RNF170 using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing (Fig. 7). RNF170 “knock-out” was specific (Fig. 7A), as other pertinent proteins (e.g. the ERAD pathway proteins p97, Hrd1, and gp78 (6, 7) and erlins 1 and 2) were expressed at the same level in control and “αT3 RNF170KO” cells. Interestingly, IP3R1 expression was enhanced ∼65% by RNF170 deletion (Fig. 7, A and D), indicating that in addition to its role in mediating the degradation of activated IP3Rs (15), RNF170 also plays a role in basal IP3R1 turnover. Ca2+ mobilization in αT3 RNF170KO cells in response to GnRH was normal (Fig. 7B), indicating that the IP3-dependent signaling pathway and IP3R activation are not perturbed by the absence of RNF170. Remarkably, deletion of RNF170 completely blocks GnRH-induced IP3R1 ubiquitination (Fig. 7C), observed using either FK2 antibody, which detects all ubiquitin conjugates (monoubiquitin, and Lys48- and Lys63-linked chains), or antibodies specific for Lys48- and Lys63-linked chains (18). In contrast, erlin2 association with IP3R1 was not blocked, indicating that association of the erlin1/2 complex with activated IP3R1 is unimpaired, consistent with the notion that it is the erlin1/2 complex that recruits RNF170 to activated IP3R1, rather than vice versa (12, 15). Thus, RNF170 does indeed catalyze the formation of all ubiquitin conjugates on activated IP3R1, and as would be expected, GnRH did not cause IP3R down-regulation in αT3 RNF170KO cells (Fig. 7D).

To directly assess the ligase activity of R198CRNF170, we sought to reconstitute IP3R ubiquitination in αT3 RNF170KO cells by stably expressing exogenous RNF170 constructs (Fig. 7E). Cell lines were obtained, although exogenous expression was less than that seen for endogenous RNF170 in control αT3 cells (data not shown). Both WTRNF170 and R198CRNF170 were capable of ubiquitinating activated IP3Rs, as indicated by increases in Lys48- and Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains and total ubiquitin after exposure to GnRH (Fig. 7E). That less ubiquitination was seen in R198CRNF170-expressing cells is most likely a consequence of lower expression level and IP3R binding of the mutant (Fig. 7E). Thus, the ligase activity of R198CRNF170 toward IP3Rs receptors in vivo appears to be qualitatively normal, and aberrant IP3R receptor ubiquitination is unlikely to account for the Ca2+ signaling deficit seen in ADSA lymphoblasts.

Discussion

Our data show that the Arg198 to Cys mutation in mouse RNF170 reduces the stability and expression level of the protein. The mutation appears to disrupt a salt bridge between TM domains 2 and 3 and leads to autoubiquitination and enhanced turnover via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. This mechanism also likely applies to human R199CRNF170 in ADSA-affected individuals, and accounts for the ∼27% reduction in the total cellular complement of RNF170. An equivalent decrease in cellular ligase activity attributable to RNF170 is likely, which could be critical to development of the disease. Alternatively, the ligase activity of mutant RNF170 in vivo could be abnormal. We did not obtain support for this notion from studies with purified components in vitro (Fig. 3D), or from analysis of IP3R1 ubiquitination in vivo (Fig. 7E), but that does not rule out the possibility that mutant RNF170 acts abnormally toward other substrates. Mutant RNF170 acting in this manner (i.e. dominantly) would be consistent with zebrafish studies, in which expression of exogenous mutant RNF170 causes aberrant development (16).

Prior to the current study, our approach to defining the function of RNF170 (and other proteins suspected to play a role in IP3R ERAD) has been to deplete them using RNA interference. Although we have had some success with this approach (13–15, 31) it has major limitations; in particular, proteins are only depleted and the effects of residual proteins are hard to assess and complicate interpretation of data from reconstitution experiments, and cells expressing short interfering RNA are often unhealthy and are available only in limited quantities. Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system (24, 25) allowed us to delete RNF170 and demonstrate, for the first time, that RNF170 catalyzes the addition of all ubiquitin conjugates to activated IP3R1. Intriguingly, this suggests that RNF170 interacts with multiple E2s, most likely Ubc13 and Ubc7, because Ubc13 is the only E2 known to build Lys63-linked chains (5, 32) and Ubc7, which builds Lys48-linked chains (5, 32), is already strongly implicated in mediating IP3R1 ubiquitination and degradation (33).

Why does the Arg198 to Cys mutation destabilize RNF170? It appears that a network of salt bridges couple TM domains 2 and 3 together, because mutation of either Arg198 or Arg200 in TM2 reduces protein expression, as do mutations to Asp231 and Asp232 in TM3. A hint as to why these mutations are apparently destabilizing is provided by the fact that they also cause RNF170 to migrate more rapidly on SDS-PAGE, indicative of a structural change in the protein that either causes more compact folding and/or alters interactions with SDS. The structural change appears to be subtle, as the Arg198 to Cys mutation did not significantly affect TM2 and TM3 insertion into the ER membrane, or interaction with the erlin1/2 complex, but could still be sufficient to trigger autoubiquitination and targeting for ERAD. Interestingly, many other E3s are known to be regulated by ubiquitination (3, 27), including the ER membrane ligase gp78 (27), which is relatively unstable and is controlled both by autoubiquitination and an additional ER membrane ubiquitin ligase Hrd1 (27). It will be interesting to see whether mutations in the TM domains of gp78 and other ER membrane ligases (8) are also destabilizing.

Although the presence of charged residues in TM domains is energetically unfavorable, such residues are often found therein, where they play important functions, often involving salt bridges (34). Intriguingly, TM domain-located charged residues are those most likely to cause disease when mutated, arginine has the highest propensity for disease causation, and the Arg to Cys mutation is relatively common because cytosine to thymine transition occurs with relatively high frequency (35). Situations very similar to that described here for RNF170 are seen in other proteins. For example, the pore architecture of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is maintained by salt bridges between arginines in TM6 (Arg347 and Arg352) and aspartic acids in adjacent TMs (36), and naturally occurring, charge altering mutations of Arg352 cause cystic fibrosis (37). Likewise, the naturally occurring R279C mutation in the prostacyclin receptor dramatically reduces protein expression (38).

Remarkably, the expression of R199CRNF170 correlated with a reduction in PAF-induced Ca2+ mobilization in lymphoblasts that was not due to a change in IP3R levels, but rather appears to result from reduced signal transduction efficiency at the IP3R locus. This was apparently not due to aberrant IP3R ubiquitination, as the ubiquitination of activated IP3R1 in cells expressing wild-type or mutant RNF170 was qualitatively identical, at least in terms of the addition of total ubiquitin and Lys48- and Lys63-linked chains. Rather, the reduction in signal transduction efficiency at the IP3R locus could be an indirect effect, if RNF170 turns out to ubiquitinate additional substrates (e.g. proteins that regulate IP3Rs), or if long-term adaptation to the ∼27% reduction in total RNF170 expression seen in ADSA lymphoblasts alters the expression of genes that govern Ca2+ signaling.

Dysregulation of Ca2+ metabolism and IP3R function is often mooted to be the cause of the neurodegeneration that underpins certain spinocerebellar ataxias and neurodegenerative diseases (39–43) and our data suggest that the same could be true for ADSA. If so, therapies aimed at boosting Ca2+ mobilization could be contemplated, similarly to the way that manipulating Ca2+ metabolism is being examined as a therapy for Huntington disease and other spinocerebellar ataxias (41–43). Interestingly, mutations to erlin2 also cause neurodegenerative diseases (44–47). Erlin2 is the dominant partner in the erlin1/2 complex, to which RNF170 is constitutively associated (11, 12, 15), and the erlin1/2 complex mediates the interaction of RNF170 with IP3Rs (15). Clearly, defining the mechanisms by which mutations to the erlin1/2 complex-RNF170 axis cause neurodegeneration will be fascinating topics for future study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Vandermark and Jacqualyn Schulman for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK049194 and the National Ataxia Foundation.

- E3

- ubiquitin ligase

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- ADSA

- autosomal dominant sensory ataxia

- TM

- transmembrane

- E2

- ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

- PAF

- platelet-activating factor

- GnRH

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- [Ca2+]c

- cytosolic Ca2+ concentration.

References

- 1. Finley D. (2009) Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 477–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kleiger G., Mayor T. (2014) Perilous journey: a tour of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 352–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. (2009) RING Domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Budhidarmo R., Nakatani Y., Day C. L. (2012) RINGs hold the key to ubiquitin transfer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Metzger M. B., Pruneda J. N., Klevit R. E., Weissman A. M. (2014) RING-type E3 ligases: master manipulators of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and ubiquitination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruggiano A., Foresti O., Carvalho P. (2014) ER-associated degradation: protein quality control and beyond. J. Cell Biol. 204, 869–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christianson J. C., Ye Y. (2014) Cleaning up in the endoplasmic reticulum: ubiquitin in charge. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 325–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neutzner A., Neutzner M., Benischke A. S., Ryu S. W., Frank S., Youle R. J., Karbowski M. (2011) A systematic search for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-associated RING finger proteins identifies Nixin/ZNRF4 as a regulator of calnexin stability and ER homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8633–8643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foskett J. K., White C., Cheung K. H., Mak D. O. (2007) Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 87, 593–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seo M. D., Velamakanni S., Ishiyama N., Stathopulos P. B., Rossi A. M., Khan S. A., Dale P., Li C., Ames J. B., Ikura M., Taylor C. W. (2012) Structural and functional conservation of key domains in InsP3 and ryanodine receptors. Nature 483, 108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wojcikiewicz R. J., Pearce M. M., Sliter D. A., Wang Y. (2009) When worlds collide: IP3 receptors and the ERAD pathway. Cell Calcium 46, 147–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2012) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor degradation pathways. WIREs Membr. Transp. Signal. 1, 126–135 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pearce M. M., Wang Y., Kelley G. G., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2007) SPFH2 mediates the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and other substrates in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20104–20115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pearce M. M., Wormer D. B., Wilkens S., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2009) An endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane complex composed of SPFH1 and SPFH2 mediates the ER-associated degradation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10433–10445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu J. P., Wang Y., Sliter D. A., Pearce M. M., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2011) RNF170, an endoplasmic reticulum membrane ubiquitin ligase, mediates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor ubiquitination and degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24426–24433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valdmanis P. N., Dupré N., Lachance M., Stochmanski S. J., Belzil V. V., Dion P. A., Thiffault I., Brais B., Weston L., Saint-Amant L., Samuels M. E., Rouleau G. A. (2011) A mutation in the RNF170 gene causes autosomal dominant sensory ataxia. Brain 134, 602–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sliter D. A., Kubota K., Kirkpatrick D. S., Alzayady K. J., Gygi S. P., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2008) Mass spectral analysis of type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35319–35328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sliter D. A., Aguiar M., Gygi S. P., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2011) Activated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are modified by homogeneous Lys-48- and Lys-63-linked ubiquitin chains, but only Lys-48-linked chains are required for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1074–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moeller J. J., Macaulay R. J., Valdmanis P. N., Weston L. E., Rouleau G. A., Dupré N. (2008) Autosomal dominant sensory ataxia: a neuroaxonal dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 116, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wojcikiewicz R. J. (1995) Type I, II and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11678–11683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bultynck G., Szlufcik K., Kasri N. N., Assefa Z., Callewaert G., Missiaen L., Parys J. B., De Smedt H. (2004) Thimerosal stimulates Ca2+ flux through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1, but not type 3, via modulation of an isoform-specific Ca2+-dependent intramolecular interaction. Biochem. J. 381, 87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bañó-Polo M., Baldin F., Tamborero S., Marti-Renom M. A., Mingarro I. (2011) N-glycosylation efficiency is determined by the distance to the C-terminus and the amino acid preceding an Asn-Ser-Thr sequon. Protein Sci. 20, 179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wojcikiewicz R. J., Tobin A. B., Nahorski S. R. (1994) Muscarinic receptor-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells is regulated acutely by cytosolic Ca2+ and by rapid desensitization. J. Neurochem. 63, 177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K. M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J. E., Norville J. E., Church G. M. (2013) RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D. A., Zhang F. (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Geest M., Lolkema J. S. (2000) Membrane topology and insertion of membrane proteins: search for topogenic signals. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 13–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weissman A. M., Shabek N., Ciechanover A. (2011) The predator becomes the prey: regulating the ubiquitin system by ubiquitylation and degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 605–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pietruck F., Spleiter S., Daul A., Philipp T., Derwahl M., Schatz H., Siffert W. (1998) Enhanced G protein activation in IDDM patients with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologica 41, 94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosskopf D., Daelman W., Busch S., Schurks M., Hartung K., Kribben A., Michel M. C., Siffert W. (1998) Growth factor-like action of lysophosphatidic acid on human B lymphoblasts. Am. J. Physiol. 274, C1573–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thastrup O., Cullen P. J., Drøbak B. K., Hanley M. R., Dawson A. P. (1990) Thapsigargin, a tumour promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 2466–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alzayady K. J., Panning M. M., Kelley G. G., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2005) Involvement of the p97-Ufd1-Npl4 complex in the regulated endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34530–34537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ye Y., Rape M. (2009) Building ubiquitin chains: E2 enzymes at work. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 755–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Webster J. M., Tiwari S., Weissman A. M., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2003) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor ubiquitination is mediated by mammalian Ubc7, a component of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway, and is inhibited by chelation of intracellular Zn2+. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38238–38246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. von Heijne G. (2006) Membrane-protein topology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 909–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Partridge A. W., Therien A. G., Deber C. M. (2004) Missense mutations in transmembrane domains of proteins: phenotypic propensity of polar residues for human disease. Proteins 54, 648–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cui G., Freeman C. S., Knotts T., Prince C. Z., Kuang C., McCarty N. A. (2013) Two salt bridges differentially contribute to the maintenance of cystic fibrosis conductance regulator (CFTR) channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20758–20767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cui G., Zhang Z-R., O'Brien A. R., Song B., McCarty N. A. (2008) Mutations at arginine 352 alter the pore architecture of CFTR. J. Membr. Biol. 222, 91–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stitham J., Arehart E., Gleim S. R., Li N., Douville K., Hwa J. (2007) New insights into human prostacyclin receptor structure and function through natural and synthetic mutations of transmembrane charged residues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 152, 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paulson H. L. (2009) The spinocerebellar ataxias. J. Neuroopthamol. 29, 227–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matilla-Dueñas A., Corral-Juan M., Volpini V., Sanchez I. (2012) The spinocerebellar ataxias: clinical aspects and molecular genetics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 724, 351–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bezprozvanny I. (2011) Role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pathogenesis of Huntington's disease and spinocerebellar ataxias. Neurochem. Res. 36, 1186–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Foskett J. K. (2010) Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels in neurological diseases. Pfugers Arch. 460, 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown S. A., Loew L. M. (2014) Integration of modeling with experimental and clinical findings synthesizes and refines the central role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 1 in spinocerebellar ataxia. Front. Neurosci. 8, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yildirim Y., Orhan E. K., Iseri S. A., Serdaroglu-Oflazer P., Kara B., Solakoğlu S., Tolun A. (2011) A frameshift mutation of erlin2 in recessive intellectual disability, motor dysfunction and multiple joint contractures. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1886–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alazami A. M., Adly N., Al Dhalaan H., Alkuraya F. S. (2011) A nullimorphiic erlin2 mutation defines a complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia locus (SPG18). Neurogenetics 12, 333–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Al-Saif A., Bohlega S., Al-Mohanna F. (2012) Loss of erlin2 function leads to juvenile primary lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 72, 510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wakil S. M., Bohlega S., Hagos S., Baz B., Al Dossari H., Ramzan K., Al-Hassnan Z. N. (2013) A novel splice site mutation in erlin2 causes hereditary spastic paraplegia in a Saudi family. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 56, 43–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]