Background: The functional significance of semicrystalline protein states in photosynthetic membranes is unknown.

Results: A mutant with high levels of semicrystalline PSII arrays shows facilitated diffusion of small lipophilic molecules but restricted mobility of large supercomplexes.

Conclusion: The results indicate that supramolecular protein organizations control photoprotection, electron transport, and protein repair.

Significance: Changes in supramolecular organization of thylakoid membranes seem to underlie acclimation processes.

Keywords: macromolecular crowding, membrane structure, photosynthesis, photosystem II, protein crystallization, nonphotochemical quenching, semicrystalline arrays, thylakoid membrane

Abstract

The structural organization of proteins in biological membranes can affect their function. Photosynthetic thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts have the remarkable ability to change their supramolecular organization between disordered and semicrystalline states. Although the change to the semicrystalline state is known to be triggered by abiotic factors, the functional significance of this protein organization has not yet been understood. Taking advantage of an Arabidopsis thaliana fatty acid desaturase mutant (fad5) that constitutively forms semicrystalline arrays, we systematically test the functional implications of protein crystals in photosynthetic membranes. Here, we show that the change into an ordered state facilitates molecular diffusion of photosynthetic components in crowded thylakoid membranes. The increased mobility of small lipophilic molecules like plastoquinone and xanthophylls has implications for diffusion-dependent electron transport and photoprotective energy-dependent quenching. The mobility of the large photosystem II supercomplexes, however, is impaired, leading to retarded repair of damaged proteins. Our results demonstrate that supramolecular changes into more ordered states have differing impacts on photosynthesis that favor either diffusion-dependent electron transport and photoprotection or protein repair processes, thus fine-tuning the photosynthetic energy conversion.

Introduction

Many functions of biomembranes are crucially dependent on precise spatial interactions between membrane-embedded proteins (1). A prime example for this interaction is the photosynthetic thylakoid membrane in plants where structural cooperation of protein ensembles ensures the conversion of solar radiation into chemical energy that fuels life on earth. The protein supercomplexes involved in this supramolecular collaboration form dynamic light-harvesting networks and electron transport (ET)3 chains for sunlight-driven charge transfer from water to terminal electron acceptors (2). A fascinating facet of supramolecular collaboration in photosynthetic thylakoid membranes is that part of the supercomplexes can form highly ordered semicrystalline arrays (3). Although these protein crystals in plant photosynthetic membranes were already recognized in the 1960s (4) and since then have been reported frequently (3), their functional significance for photosynthesis remains unknown. Semicrystalline arrays seem to have high physiological relevance because their abundance is controlled by different abiotic factors, including temperature, light, or osmotic potential (3). The fact that multiple environmental factors trigger changes of the protein organization from disordered to a crystalline state points to a central biological role of this rearrangement and highlights the need to understand their functional implications. Detailed electron microscopic studies have established that protein arrays occur only in strictly stacked so-called grana thylakoid areas and that they consist of the dimeric water-splitting photosystem (PS) II supercomplex with attached light-harvesting complex (LHC) II (3, 5).

It has been hypothesized that the ordering of protein complexes in grana thylakoid membranes could be a strategy to optimize lateral diffusion processes (6). This hypothesis emerged from a conceptual problem for diffusion-dependent reactions in stacked grana membranes, which is based on the fact that the very high protein density in these membranes (macromolecular crowding) can significantly impair the mobility of membrane components (7, 8). Macromolecular crowding is a common feature of bioenergetic membranes (6). Evidence for severe restriction in mobility of grana components by macromolecular crowding comes from both computer simulation and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments (7, 9–11). A restricted mobility in grana membranes is in stark contrast to the necessity of rapid lateral molecular diffusion required for proper membrane function. Diffusion-dependent reactions in grana thylakoid membranes can be divided in reactions that require the mobility of small hydrophobic molecules and processes that involve migration of larger protein complexes. Examples for diffusion of small hydrophobic molecules are electron shuttling between PSII and cytochrome b6f (cyt b6f) complexes by plastoquinone (PQ) and diffusion of xanthophylls required for photoprotective nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ). Examples for migration of protein complexes include large scale redistributions of LHCII complexes during low-light acclimation by state transitions (12), high-light induced NPQ (13, 14), and protein traffic between stacked grana and unstacked so-called stroma lamellae for the repair of photodamaged PSII (15–18). Until now, it was not possible to test the hypothesis that protein ordering facilitates membrane mobility.

How might the formation of semicrystalline arrays impact lateral diffusion in crowded membranes? First, recent electron tomographic data on granal PSII arrays indicate a 1–2-nm lipid-filled gap between the protein rows (5). This lipidic channel could act as a diffusion highway for small molecules (PQ or xanthophylls) by switching from a two-dimensional diffusion process as found in disordered membrane areas to a one-dimensional diffusion in the lipid channel. Second, the protein density in PSII arrays is higher compared with disordered membrane regions (as determined in this study). In consequence, reorganization of part of the grana membrane into a tightly packed crystalline state can create less protein crowding and higher mobility in the remaining disordered grana areas. Third, besides these advantages for lateral diffusion processes, the mobility of PSII localized in semicrystalline arrays is expected to be highly restricted. That could impair the repair of photodamaged PSII that has to escape from stacked grana to reach the molecular repair machinery located in unstacked stroma lamellae. This report will address these possibilities. Taking advantage of a mutant that constitutively forms semicrystalline arrays, we have the possibility to systematically study functional implications of protein crystals in photosynthetic membranes.

Experimental Procedures

Growth Conditions and Thylakoid Membrane Preparation

Arabidopsis thaliana wild type and fad5 plants were grown for 7 to 8 weeks at 110 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 and 9 h of daylight. Thylakoids were isolated from intact chloroplasts according to Ref. 5, with modifications for Arabidopsis. In detail, about 30 g of leaf material were blended in 330 mm sorbitol, 50 mm Hepes (pH 7.5) (KOH), 2 mm EDTA, 15 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm CaCl2, and 0.1% (w/v) BSA filtered through 1 layer of Miracloth and 4 layers of muslin. Chloroplasts were obtained from the homogenate by pelleting them at 3000 × g. The chloroplasts were shocked in 50 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 5 mm MgCl2 for 2 min, and larger unsolubilized material was pelleted at 200 × g for 1 min. Intact thylakoids were obtained by centrifugation of the supernatant at 3000 × g for 10 min and washed in 0.1 m sorbitol, 50 mm Hepes, 15 mm NaCl, and 10 mm MgCl2 (washing buffer).

Grana Preparations

Grana were isolated from intact thylakoid membranes by adding 400 μl of a 2% (w/v) digitonin solution, which was added to 2 ml of thylakoid suspension with a Chl concentration of 400 μg/ml. The mixture was stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Unsolubilized thylakoids were pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant with grana membranes was pelleted at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and grana were washed in the washing buffer mentioned above. Chl concentrations were determined spectroscopically in 80% (v/v) acetone (19).

Polarographic Oxygen Measurements

Cyt b6f complex-dependent electron transport rates were measured using a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech) at 20 °C in buffer containing 300 mm sorbitol, 50 mm Hepes (pH 7.6) (KOH), 7 mm MgCl2, and 40 mm KCl in the presence of 100 μm methyl viologen (MV), 1 mm sodium ascorbate, 1 μm nigericin, and 1.5 mm duroquinol. Excitation light was saturating (>1000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1). Reduced duroquinol was prepared as described in Ref. 20.

Difference Absorption Spectroscopy and Calculation of LHCII/PSII Ratios

Protein Complex Quantifications

Difference spectroscopic quantification of cyt b559 and P700 was used to determine the content of PSII and PSI, respectively, and the cyt b6f complex was determined by quantification of cyt f and cyt b6 as described in Ref. 21. Baseline-corrected coefficients of 28.7 for cyt f and of 22.0 mm−1 cm−1 for cyt b6 were used. Signals were recorded using a Hitachi U3900 spectrometer (2-nm slit width, 530–580 nm), and the spectra were analyzed as described previously (21). P700 detected as an 810- minus 900-nm difference signal was measured with a flash spectrophotometer on dark-adapted grana samples at a concentration of 30 μg/ml after addition of 10 μm MV and 1.5 mm sodium ascorbate. Quantitative oxidation was induced by a 400-ms saturation pulse. To determine Chl/P700 ratios, Chl was measured according to Ref. 19, and P700 concentration was determined by using the differential extinction coefficient (9.60 mm−1 cm−1) as described previously (22). Data were analyzed with SigmaPlot 11 software.

The ratio of LHCII3 and PSII-core for grana thylakoids was calculated as described previously (23). The calculation was based on the assumption that the measured Chltotal/PSII ratio was given by the sum of Chls bound to PSII (Chl/PSII), LHCII3 (Chl/LHCII3), and PSI-LHCI (Chl/PSI) divided by the amount of PSII. From high resolution structures, it is known that the Chl/PSII is 63 and the Chl/LHCII3 is 42 (23). The Chl/PSI is 173 taking the four LHCI into account or 112 without LHCIs. The range of LHCII3/PSII ratios in Table 2 gives the numbers of the two different Chl/PSI ratios.

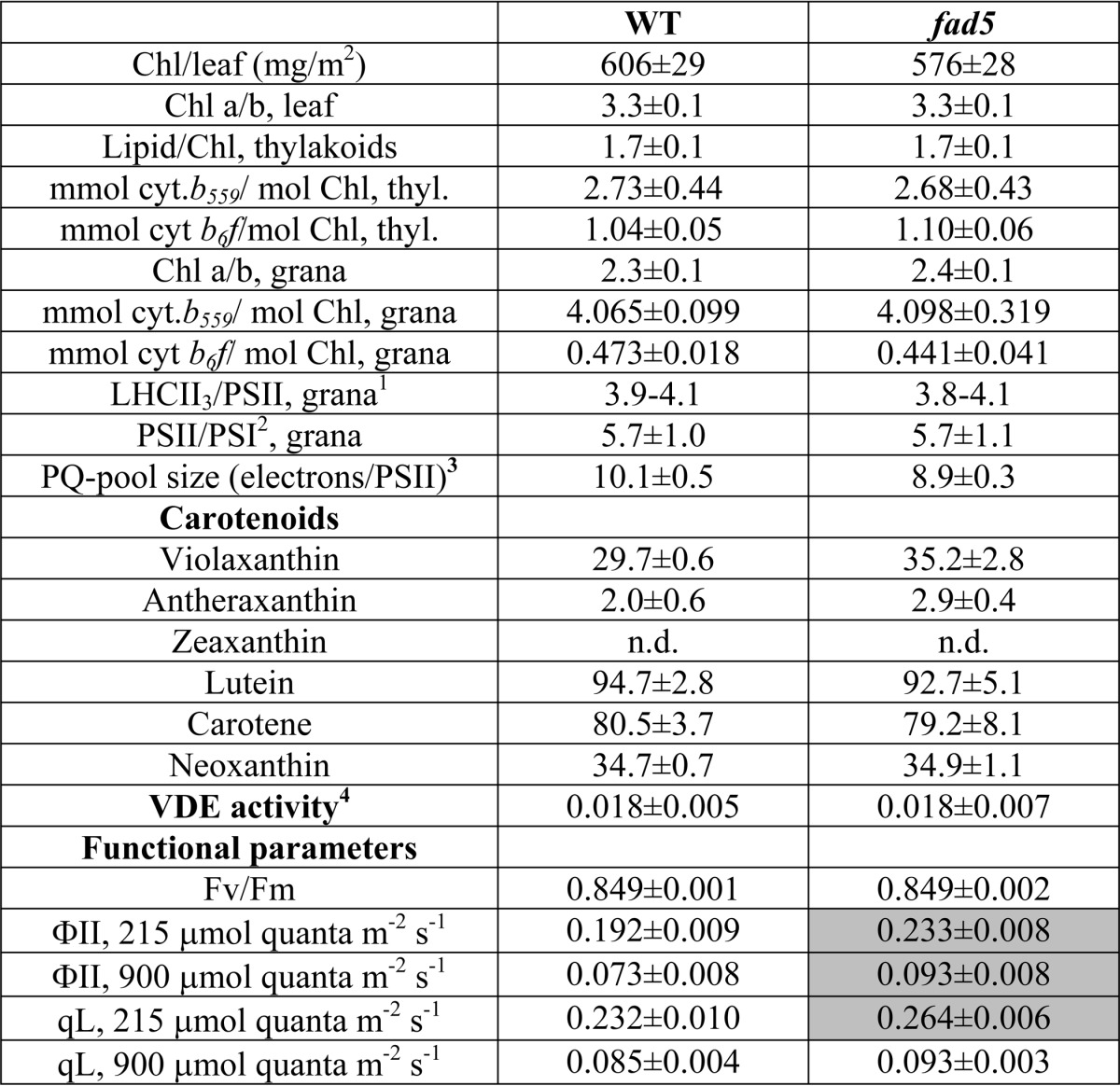

TABLE 2.

Characterization of WT and fad5 mutant

Mean values with standard deviation are shown. n.d. means not detectable. Carotenoid content is given in millimoles/mol of total Chl.

1 Data were calculated from the Chl/cyt. b559 and PSII/PSI ratios (see under “Experimental Procedures”).

2 PSI was determined by difference absorption spectroscopy of P700.

3 The PQ pool size was estimated from the area above the chlorophyll fluorescence induction curve in the presence and absence of DCMU.

4 VDE activity is given as initial rate of violaxanthin de-epoxidation in micromoles (mg of protein)−1 min−1. Violaxanthin de-epoxidation was induced by sodium ascorbate addition and measured on aqueous lumen extracts from isolated thylakoids (see “Experimental Procedures” for further details). The differences between fad5 and WT are not statistically significant (p = 0.056). Gray shading of cells indicates statistically significant differences (t test, p < 0.05).

Time Resolved Difference Absorption Spectroscopy

Difference absorption kinetics of cyt f, b6, and P700 for intact isolated Arabidopsis thylakoid membranes (freshly osmotically shocked chloroplasts) was recorded with a home-built flash spectrometer. Cytochrome f redox kinetics was monitored following absorption changes at 545, 554, and 572 nm and cyt b6 kinetics from absorption changes at 545, 563, and 572 nm (22). P700 signals were derived as described above. Redox changes of QA were derived from chlorophyll fluorescence (22). All redox changes were measured with the same samples. For inducing redox changes, dark-adapted samples were illuminated with saturating pulses (200 ms and 630 nm) in the presence of MV (100 μm), 2 μm nigericin, 5 μm valinomycin, and 5 mm sodium ascorbate in measuring buffer (330 mm sorbitol, 7 mm MgCl2, 40 mm KCl, 25 mm Hepes (pH 8.0)). Nigericin and valinomycin (uncouplers) prevent feedback effects of the light-induced pmf on electron transfer. MV is an efficient electron acceptor for PSI and prevents cyclic electron transport reactions. A measuring cycle averages four repetitions for each wavelength.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot Analysis

Protoplasts were solubilized and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described previously (24). Protoplast samples containing 0.5 nmol of Chl a were loaded in each lane. The anti-D1 antibody was kindly provided by Prof. Anastasios Melis (University of California, Berkeley), and the anti-CP24 antibody was kindly provided by Prof. Stefan Jansson (Umeå University). Proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting kit (SuperSignal West Femto, Thermo Scientific). D1 immunoblot of photoinhibited leaf disc (Fig. 10D) was performed as described previously (25). In detail, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE (11.5% polyacrylamide gel containing 6 m urea) were electroblotted onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with antibody raised against the C terminus of the D1 protein (Agrisera) and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoreactive bands were detected by fluorography using the ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare). The loading control actin (Fig. 10D) was detected by a monoclonal antibody against the plant actins (A0480, Sigma). D1 and actin contents were determined from densitometric quantification of the Western blot bands by using ImagePro Plus software. The FtsH level was checked using an anti-FtsH antibody from Agrisera (AS111789) and the PS II phosphorylation level, using an anti-phosphothreonine antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc.). The sample storage buffer for phosphorylated thylakoids contained 10 mm NaF and phosSTOP to prevent dephosphorylation. For both Western blots, samples were loaded on an equal Chl basis (5 μg of Chl/sample). The gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were done as before.

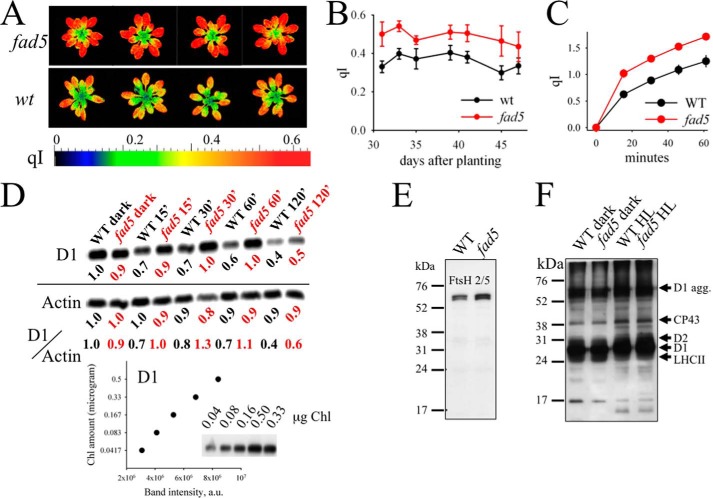

FIGURE 10.

fad5 mutant shows higher photoinhibition and an impaired PSII repair cycle. A, false color images for the qI parameter for fad5 and WT plants. B, qI parameter for whole plants determined as a function of time. Data represent the mean with standard error of 9 (fad5) and 18 (WT) plants. C, photoinhibition of isolated protoplasts induced by white light of 2000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 at room temperature. For qI determination at different time points, strong light was switched off for 3 min and Fv′ was determined after this time. This procedure allows elimination of the reversible qE component that relaxes in a few minutes. Data represent the mean with standard error of 10 (WT) and 11 (fad5) samples. D, D1 dilution series and HL-induced changes in D1 content at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min of HL. The Western blots are representative of three independent analyses. The time indicates the duration of the strong light (1200 μmol quanta m−2 s−1) that induces PSII photoinhibition. All the time series samples have been treated with 1 mg/ml lincomycin and were loaded on the gel on an equal Chl basis (0.167 μg of Chl/sample). The loading control actin was detected in a similar gel with a higher sample concentration (1.0 μg of Chl/sample). The band intensities of D1 and actin, normalized to respective WT dark samples, are given below each lane. To account for the separate D1 and actin blots, D1 to actin ratios were also shown. The graph at the bottom shows the nearly linear correlation between D1 amount and the band intensity. E, Western blot analysis of the FtsH protein in the dark-adapted leaves. FtsH level is slightly elevated in the fad5 mutant. F, PSII-core phosphorylation level of dark and HL-treated samples. The antibody is directed against the phosphothreonine. The HL-induced increase in phosphorylation levels of D1, D2, and CP43 is well documented and results from the activation of the STN8 kinase. No differences in phosphorylation are visible between WT and fad5 mutant.

Pigment Analysis

The Chl and carotenoid content of intact leaves was quantified by reversed phase HPLC according to the method described previously (26). Intact leaves were carefully ground, and pigments were extracted with 100% acetone. Pigment extracts were stored up to 7 days at −80 °C until used for HPLC analysis.

VDE Activity

VDE activity was measured in vitro on luminal extracts prepared from intact thylakoid membrane.

Violaxanthin Isolation

Violaxanthin was extracted from dark-adapted Arabidopsis leaves in a chloroform/distilled H2O/methanol mixture. The organic phase was dried down and resuspended in 100% acetone. The extract was separated by TLC in a mobile phase containing 100 ml of hexane, 12 ml of isopropyl alcohol, and 1 ml of H2O. The second line from the bottom containing violaxanthin was quickly scraped off and dissolved in 1 ml of methanol. Silica was separated by centrifugation. The identity of violaxanthin was verified spectroscopically (27).

Lumen Extraction

The aqueous lumen of thylakoids was isolated as described previously (28) and then used for the in vitro de-epoxidation assay. Determination of the total protein content of the extracts was done according to Ref. 29.

VDE Activity

VDE activity was assayed spectrophotometrically (Hitachi U3900) where activity was determined from the initial rate of absorbance change at 502 minus 540 nm according to Ref. 27. The reaction mixture contained 15 μl of 270 μm MGDG in methanol, 15 μl of 10 μm violaxanthin in methanol, and 250 μl of 200 mm citrate buffer (pH 5.2). Variable amounts of luminal extracts and distilled H2O were added to 0.495 ml. After a stable absorbance baseline was established, 5 μl of 3 m sodium ascorbate was added to initiate reaction, and spectra were recorded after 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min (27). VDE activity is derived from the initial slope of absorption changes and expressed in micromoles of violaxanthin de-epoxidation (mg protein)−1 min−1 (27). For conversion of absorption change to micromoles of violaxanthin de-epoxidation, an extinction coefficient (502 − 540 nm) of 63 mm−1 cm−1 was used (27). We checked that the different fatty acid compositions in WT and fad5 do not change VDE activities. Therefore, VDE activities were measured with MGDG isolated from WT and fad5 mutant, respectively. The fatty acid profile for WT-MGDG is 1.9 ± 0.2% (16:0), 1.2 ± 0.2% (16:1Δ3), 31.4 ± 0.3% (16:3), 0.3 ± 0.6% (18:0), 2.5 ± 0.4% (18:2), and 62.7 ± 0.2% (18:3). The profile for the fad5-MGDG is 18.2 ± 0.4% (16:0), 2.5 ± 0.0% (16:1Δ3), 2.0 ± 0.0% (16:3), 2.1 ± 0.1% (18:0), 2.6 ± 0.1% (18:2), and 72.5 ± 0.4% (18:3). The rates are almost identical.

In Vivo Fluorescence, NPQ, and Zeaxanthin Measurements

Measurements were carried out on dark-adapted leaves at room temperature with the flash spectrophotometer mentioned above at different light intensities. Minimum fluorescence (Fo) was measured over 2 s with a measuring light of 2 μmol quanta m−2 s−1, and maximum fluorescence (Fm) was determined with a 0.6-s light pulse of 1870 μmol m−2 s−1. NPQ was calculated according to the following equation: NPQ = (Fm − F′m)/F′m, where Fm is the maximum Chl fluorescence from dark-adapted leaves and F′m the maximum Chl fluorescence under actinic light. Zeaxanthin was measured alongside the NPQ measurement at 505 nm. The data were further corrected through the signals at 520, 535, and 488 nm according to Ref. 30. The ECS was measured at 520 nm.

PQ-Pool Size

The number of total electrons that can enter the PQ-pool (PQ-pool size), given in Table 2, is derived from the ratio of the area of growth above Chl fluorescence induction curves in DCMU-free and DCMU-poised (100 μm) leaf discs. Leaf discs were infiltrated with tap water containing 150 mm sorbitol to avoid osmotic artifacts. Fluorescence induction was performed with a home-built instrument according to Ref. 31.

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP) on Thylakoid Membranes and Lipid Bilayers

Isolated thylakoids were labeled with 10 μm lipophilic dye D3832 (Molecular Probes). FRAP measurements were carried out by a Leica TCS SP5 laser-scanning confocal microscope. D3832 and Chl fluorescence were measured in parallel. D3832 was excited by a 543 nm HeNe laser line and detected between 550 and 600 nm. The Chl fluorescence was excited by a 633 nm HeNe laser line, and emission was detected between 650 and 720 nm. For FRAP, total and line bleaches across the sample were performed. A series included the following: eight pre-bleaches; the bleach (thin line); 10 post-bleaches with 3-s separations; and 10 post-bleaches with 10-s separations. The total bleaches detect the recovery of bleached pigments and were subtracted from the line-bleached data to visualize only diffusion-based fluorescence recovery. Data were analyzed through SigmaPlot 11 as described previously (10).

Atomic Force Microscopy

Sample Preparation

fad5 and WT grana samples at a concentration of 30 μg/ml were diluted in 100 μl of destacking buffer (15 mm MES (pH 6.5)), 10 mm KCl, and 0.5 mm EDTA. Samples were then sonicated for 1 min. 100 μl of the destacked grana solution was then placed onto a freshly cleaved mica substrate (∼100 mm2) for 2 min, and the sample was rinsed 10 times with distilled water with 200 μl per rinse. The samples were dried under a steady, gentle nitrogen stream for 2 min.

AFM Imaging

The grana were imaged in tapping mode with a Dimension 3000 AFM (Veeco Instruments, Plainview, NY) with silicon dioxide tapping mode AFM cantilevers (catalog no. OMCLAC160TS-W2, 7-nm tip radius, 15-μm tip height, 42 newtons/m spring constant, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). A total of 20 grana patches for WT and 19 for the fad5 mutant were analyzed to derive the particle densities and the fraction of arrayed grana thylakoids.

Calculation of LHCII Fraction in Disordered and Ordered Grana Thylakoids in fad5 Mutant

The single particle TEM analysis (C2S2M2 supercomplex) gives a trimeric LHCII (LHCII3) to PSII-core ratio of two for the semicrystalline arrays (R1 = 2, see Equation 1 below). The overall measured LHCII3/PSII ratio in fad5 grana (Rtotal) is four (Table 2). Knowledge of the relative fraction of grana organized in arrays (Farr, 0.5 for fad5) and the fraction of disordered grana (Fdis = 1 − Farr) allow calculation of the LHCII3/PSII ratios for disordered regions (R2) by solving Equation 1 for R2,

It follows that the LHCII3 to PSII-core ratio in disordered grana regions is 5.8 ± 0.2 for fad5 (the ± numbers indicate the range of LHCII3/PSII ratios in Table 2). From the LHCII3/PSII-core ratios and the PSII densities (from AFM) for arrayed and disordered grana in fad5, the LHCII3 densities in both regions are given to 4000 LHCII3 μm−2 (arrayed, 2·2000 PSII μm−2) and 8404 LHCII3 μm−2 (disordered, 5.8·1449 PSII μm−2). Weighted by the fraction of arrayed and disordered membrane regions (1:1, from AFM), it follows that 68% of LHCII3 in fad5 grana are localized in disordered regions (100%·0.5· 8404/(0.5·8404 + 0.5·4000)) and the rest in arrayed regions.

EM and Single Particle Analysis

Specimens containing grana thylakoid membranes were prepared by negative staining with 2% uranyl acetate on glow-discharged carbon-coated copper grids. Transmission electron microscopy was carried out on a Philips CM120 electron microscope equipped with a LaB6 tip, operated at 120 kV. Images were recorded with a Gatan 4000 SP 4K slow-scan CCD camera at ×80,000 magnification with a pixel size of 0.375 nm at the specimen level after binning the images to 2048 × 2048 pixels. GRACE software was used for semi-automated data acquisition (32). Electron micrographs were bandpass-filtered prior to analysis to improve an image contrast. Sub-areas of semi-crystalline arrays of PSII supercomplexes were analyzed using a single particle averaging approach with the Groningen Image Processing (GRIP) software, including reference alignments and averaging of aligned projections. Sets of sub-areas (192 × 192 pixels) of PSII arrays selected from individual electron micrographs were repeatedly aligned and finally summed to provide two-dimensional maps.

Phenomics

The photoinhibitory qI parameter was determined for intact Arabidopsis plants in the Phenomics Facility at Washington State University consisting of a greenhouse (artificial illumination) and an optical screening robot. Nine fad5 mutants and 18 WT plants were grown in the greenhouse with a 9-h day period of 200 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 illumination in daily temperatures of 21 °C in the dark and 23 °C in the light. Measurements were performed every 2–4 days while the plants were between about 4 and 6 weeks old. The Fluorcam XYZ system (PSI Co., Drasov, Czech Republic) is a mobile and programmable fluorescence imaging robot capable of moving throughout the growth chamber on a gantry, performing automated measurements utilizing blue (455 nm) LEDs to excite chlorophyll fluorescence. The fluorescence is captured by a Fluorcam 2701 LU camera equipped with a fluorescence filter. The qI parameter was determined as NPQ values in the dark determined 2 min after a 4-min illumination period with 200 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. Measurements were performed with plants that were at the end of the night period.

Results

Establishing a Model Plant for Studying Semicrystalline Protein Formation

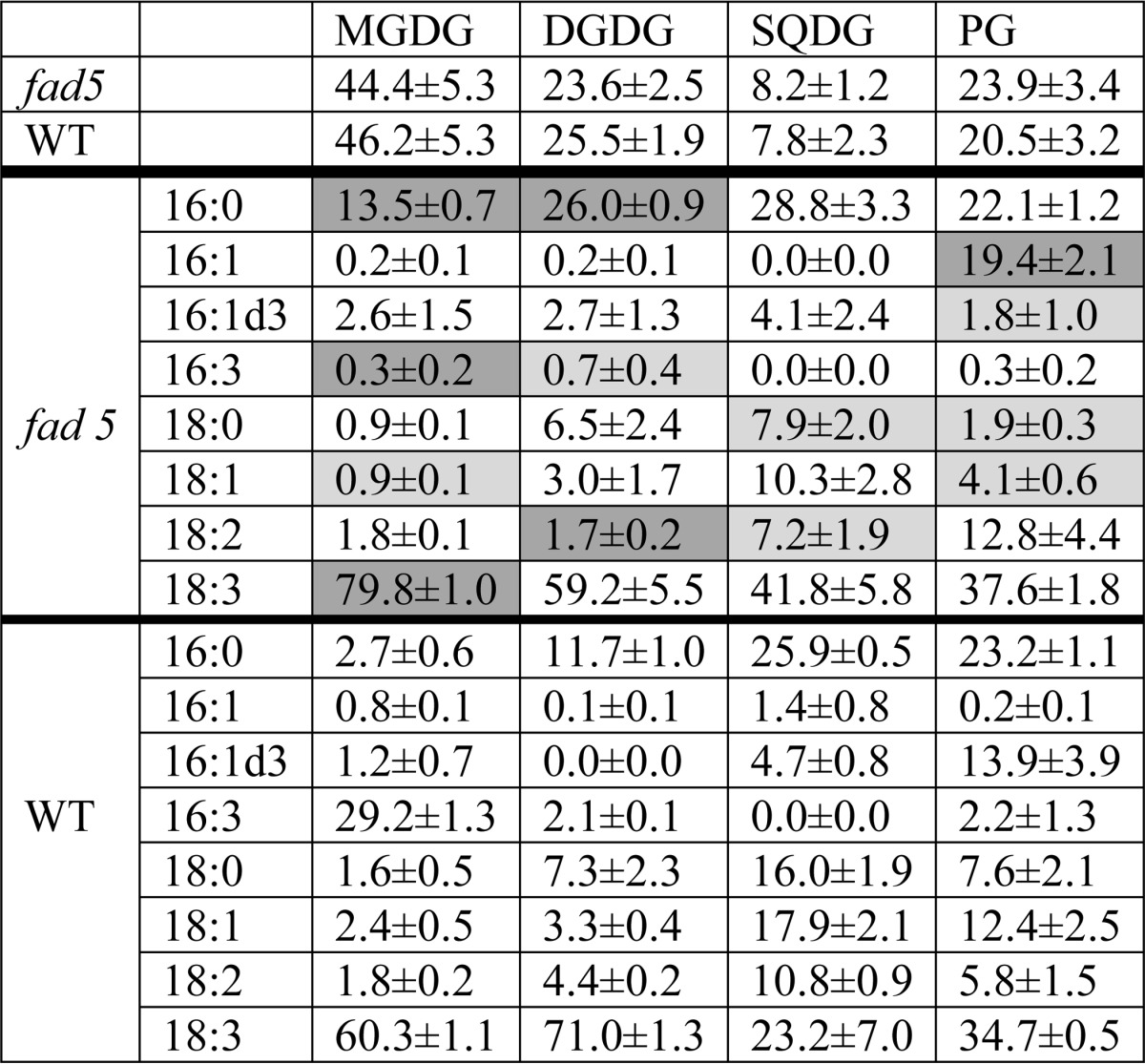

An adequate model plant for studying functional implications of semicrystalline protein arrays requires that only the supramolecular arrangement has been altered. In this respect, we tested the fatty acid desaturase 5 (fad5) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana (33), because it has been reported by using freeze-fracture electron microscopy that this mutant constitutively forms protein crystals in grana with high abundance (34). Its model system credentials, however, have not yet been ascertained. Other mutants also form semicrystalline protein arrays in thylakoid membranes but have specific drawbacks as addressed under the “Discussion” (see under “Comparison with Other Mutants”). The fad5 mutant has a defective Δ9 fatty acid desaturase enzyme leading to a drastic decrease of 16:3 fatty acids in the main thylakoid lipid, monogalactosyl-diacylglycerol, accompanied by an increase in 16:0 and 18:3 fatty acids (Table 1) (33). Because studies on other mutants showed that different types of semicrystalline arrays exist, characterized by different lattice constants and PSII supercomplex compositions (3, 8), we checked whether the fad5 mutant forms the same crystal type as WT plants. We therefore applied AFM and TEM, combined with single particle analysis on isolated grana thylakoids (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Lipid and fatty acid composition of WT and fad5 thylakoid membranes

All numbers are in %. Values for lipid class quantification (2nd and 3rd rows) are the means ± S.E. of 10–14 determinations. The fatty acid pattern is the means ± S.E. of four independent measurements. Significant changes (p < 0.05) of fad5 relative to WT are highlighted in light gray and highly significant changes (p < 0.001) in gray.

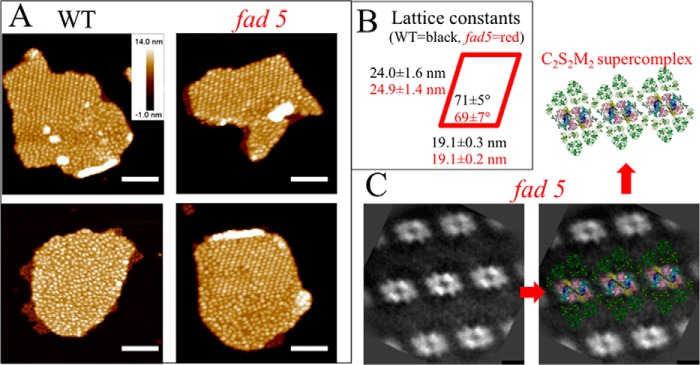

FIGURE 1.

fad5 mutant forms more semicrystalline protein arrays of the same type as WT in grana thylakoids. A, AFM images showing semicrystalline arrays and disordered grana regions. Analysis of total grana areas of 2.7 μm2 (WT) and 1.5 μm2 (fad5) reveals that 16% of WT grana and 50% of fad5 grana are organized in semicrystalline arrays, respectively. Scale bar, 200 nm. B, protein arrays in fad5 grana have a statistically indistinguishable structure compared with the WT as quantified by the lattice constants derived from Fourier transformation of AFM images of the crystalline parts in WT and fad5. C, single particle image analysis of TEM images for fad5 grana. High resolution structural models of the C2S2M2 supercomplex were superimposed by taking the brighter PSII-core region as a marker. Scale bar, 10 nm.

AFM images reveal densely packed particles sticking out of the grana membrane surface (white spots in Fig. 1A) that are either arranged completely disordered (bottom left) or partially semicrystalline and partially disordered. These particles represent the luminal protrusion of the PSII and cyt b6f complex (35) and can be used as topographic markers to analyze the abundance and geometry of semicrystalline PSII arrays. Statistical analysis revealed that the fraction of arrayed grana areas in the fad5 mutant is 50% and 16% in the WT. Areas were determined to be crystalline when more than three rows of PSII arrays were visible. Fractions of arrayed and nonarrayed areas in grana membranes were first selected by circling them in ImagePro and then determined the area size of each type.

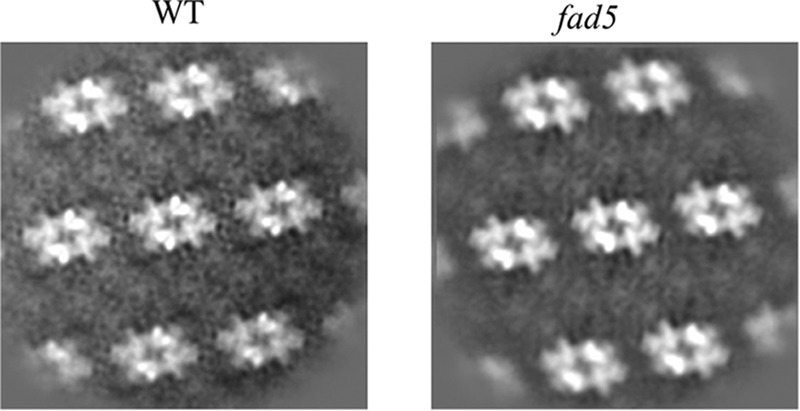

Furthermore, from Fourier transformation of the semicrystalline arrays in both genotypes, the lattice constants show no statistical differences (Fig. 1B). The strong similarity in the crystal architecture in the fad5 mutant and WT is further supported by single particle TEM analysis showing that the arrays in fad5 (Fig. 1C) and in WT (Fig. 2) are constituted of the so-called C2S2M2 supercomplex (Fig. 1C, C = PSII-core, S = strongly bound LHCII, and M = medium bound LHCII, 3). Thus, it is safe to conclude that the fad5 mutant forms the same type of semicrystalline protein arrays in grana thylakoids as the WT but with much higher abundance (50% compared versus 16% in WT).

FIGURE 2.

Single particle image analysis of EM images for fad5 and WT grana. See legend to Fig. 1 for details.

Next, we analyzed the composition of fad5 thylakoid membranes. A thorough biochemical and functional analysis is summarized in Table 2. It turns out that the Chl, carotenoid, and thylakoid lipid content is very similar in WT and fad5 mutant. In Ref. 36, it was reported that the Chl content is 30% lower in the fad5 mutant. A possible explanation for this inconsistency is that plants in Ref. 36 grew under 100% higher light intensity than in our study (300 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 versus 100–150 μmol quanta m−2 s−1). As detailed below, PSII in fad5 is more vulnerable to photoinhibition, which could eventually lead to the partial chlorotic fad5 phenotype in Ref. 36. The xanthophyll cycle pool size (violaxanthin + antheraxanthin + zeaxanthin) is slightly (20%) increased in fad5. More in-depth quantifications of grana thylakoids reveal that the PSII, LHCII, and PSI contents in grana thylakoids of WT and fad5 plants were statistically indistinguishable (Table 2). For grana membranes from WT and the fad5 mutant, the trimeric LHCII to monomeric PSII ratio was approximately 4. Thus, fad5 has very similar thylakoid membrane composition as WT membranes.

Functional information on the photosynthetic apparatus was deduced from analysis of Chl fluorescence data on intact leaves (Table 2). The maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm parameter) was identical in fad5 and WT plants. This indicates that PSII is fully functional in the mutant. Linear photosynthetic electron flux monitored by the photochemical quantum efficiency parameter ΦII (37) at two different light intensities is 20–30% higher in fad5, in accordance with the previous study (38). It is interesting to note that in the study of Kunst et al. (38), the ET rates for PSII and PSI alone were not different between fad5 and WT. This points to the possibility that the higher ET rate in fad5 is caused by a more efficient intersystem ET. Indeed, we found that the PQ-pool is more oxidized in fad5 (qL parameter (Table 2) (37), suggesting that electron shuttling between PSII and PSI by the small hydrophobic electron carrier PQ is facilitated, as examined in detail below. Overall, it turns out that the composition of fad5 and WT thylakoid membranes is very similar and that only the level of protein ordering is increased, making this mutant an attractive system to study the functional impact of semicrystalline arrays.

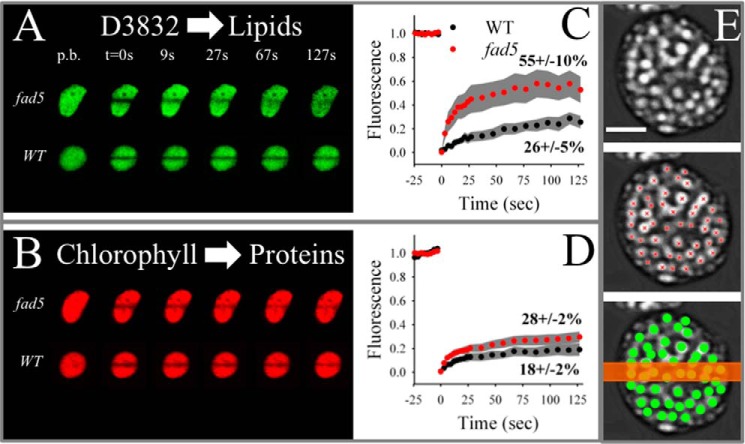

Protein Crystal Formation Accelerates Molecular Diffusion in Thylakoid Membranes

Having established fad5 as a model system for studying semicrystalline protein arrays, we then tested the hypothesis that protein ordering increases the mobility of thylakoid membrane components. Therefore, we performed diffusion measurements probing lipid and protein mobility in intact thylakoid membranes by FRAP. For measuring lipid mobility in crowded thylakoid membranes, the green fluorescence dye D3832 (Molecular Probes) was used. Diffusion of this dye was measured in parallel with red Chl autofluorescence that probes diffusion of pigment protein complexes, mainly PSII and LHCII (10, 39). For FRAP analysis, a small stripe in stained thylakoid membranes was irreversibly bleached by a high laser intensity (t = 0 s in Fig. 3, A and B), and the fluorescence recovery was recorded in time with low laser power. As seen in the FRAP image series in Fig. 3, A and B, the bleached stripe recovered significantly faster in fad5 for both the lipid analogue D3832 and Chl fluorescence. Statistical analysis of the FRAP measurements for D3832 shows a doubling in the fraction of mobile dyes (indicated by the percentages in Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the kinetics of the mobile fraction was faster in fad5, i.e. the curve reached its saturation level earlier. From these results, it follows that the overall mobility of lipophilic components in fad5 thylakoid membranes was significantly increased compared with WT thylakoid membranes. The higher mobility of small lipid-like molecules in fad5 can be caused by higher mobility in the lipid bilayer or by reorganization into a semicrystalline state. The former is unlikely because fluorescence polarization studies with diphenyl-hexatriene show unaltered lipid micro-diffusion (nanometer range) in fad5 thylakoid membranes compared with the WT (38). The diphenyl-hexatriene study provides clear evidence that the mobility in the lipid bilayer itself is not affected by the altered fatty acid composition in the mutant. The comparison of FRAP and diphenyl-hexatriene fluorescence polarization measurements indicates that long range diffusion of small molecules in thylakoid membranes is faster in the fad5 mutant because of the protein reorganization into semicrystalline state.

FIGURE 3.

FRAP analysis on isolated thylakoid membranes shows higher diffusion of photosynthetic components in the fad5 mutant. A and B, examples for D3832 (A) and Chl fluorescence (B) time series. The line bleach was induced at time point 0 (t = 0 s) p.b., pre-bleach images. D3832 signal is a measure for lipid diffusion. Note the faster recovery of D3832 fluorescence in the fad5 mutant. Chl fluorescence measures mainly LHCII and PSII mobility. C, statistical analysis of the FRAP data for D3832. Pigments were bleached at time point 0 (corresponds to t = 0 s in Fig. 2A). Data represents the mean of 12 (WT) and 21 (fad5) measurements with 95% confidence interval given as gray areas. The percent values give the mobile fraction that recover in the course of the experiment. D, same analysis as in C but for the chlorophyll fluorescence. E, schematics demonstrating the relation between the width of the bleach stripe (typically 700 nm, orange bar) and the density and sizes of grana discs (green circles) in the FRAP experiment shown in A and B. The gray images are trimmed CLSM images showing grana thylakoids as bright spots (modified from Ref. 75). Red crosses indicate the centers of individual grana piles. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Similar to the increased lipid mobility, the overall protein mobility (measured by Chl fluorescence) was nearly doubled in fad5 thylakoid membranes (Fig. 3D). As illustrated in Fig. 3E, the bleach line of the FRAP experiment (t = 0 s in Fig. 3, A and B) covers about a dozen grana stacks. Because each stack consists of several grana membranes, the mobility data in Fig. 3 represents an averaged view of roughly 100 grana membranes. The limited recovery of fluorescence indicates that some fluorophores are moving very slowly within grana (relative to the time frame of the experiment of 125 s) and/or that total grana are bleached and the diffusion of unbleached fluorophores from adjacent grana is very slow. The latter should also be determined by mobility in the adjacent grana because the mobility in unstacked thylakoid regions is much faster compared with grana thylakoids, i.e. not rate-limiting (39). It thus follows that higher amplitude of fluorescence recovery as measured in fad5 indicates higher molecular mobility mainly in its stacked grana.

Functional Implications of Semicrystalline Array Formation for the Diffusion of Small Lipophilic Molecules

The FRAP data with D3832 indicates that lipid-like molecules diffuse faster in the thylakoid lipid bilayer in fad5. Therefore, it is expected that the mobility of PQ and xanthophylls in crowded grana thylakoid membranes (see Fig. 6A for an illustration of protein crowding in grana) is affected, which would impact PQ-dependent ET and xanthophyll-dependent NPQ. First, we analyzed PQ-dependent ET reactions by time-resolved (milliseconds) difference and fluorescence spectroscopy. It is difficult to monitor PQ electron transfer from PSII to the cyt b6f complex directly, but it is rather straightforward to measure its direct reaction partners, i.e. QA (primary quinone acceptor of PSII) as well as cytochrome f (cyt f) and cytochrome b6 (cyt b6) of the cyt b6f complex (see schematic in Fig. 4A). For this purpose, we applied a 200-ms saturating light pulse that quantitatively reduces QA (QA−) and the PQ-pool, whereas cyt f and P700 are completely oxidized (cyt f+, P700+). This “redox crossover” is well established and is due to the fact that the rate-limiting step in linear electron transport is the plastoquinol (PQH2) oxidation at the cyt b6f complex (40). Measurements were done with fresh thylakoid membranes in the presence of MV (electron acceptor for PSI (7, 22)). The addition of the ionophore valinomycin (41) allows detection of cyt b6 redox kinetics, which is in the reduced state at the end of the light pulse (b6−) due to Q-cycle activity (42). Starting from this defined redox situation at the end of the light pulse (Fig. 4A, left, t0), we examined the relaxation in the subsequent dark period (Fig. 4B). What is obvious from Fig. 4B is that all PQ-dependent redox reactions are faster in fad5 compared with the WT. The simplest explanation for this acceleration is that PQ and PQH2 find the binding niches at PSII (QB site) and at the cyt b6f complex (Qo site and Qr site) faster, i.e. by accelerated PQ diffusion in membranes with semicrystalline protein arrays.

FIGURE 6.

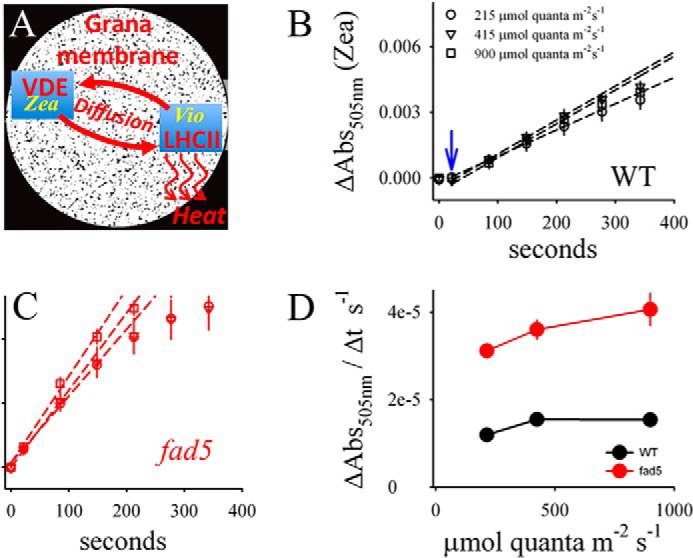

Zea induction is accelerated in the fad5 mutant. A, schematic showing the diffusion-dependent enzymatic conversion from Vio to Zea. Because the concentration of VDE is low in thylakoid membranes (44), long range xanthophyll diffusion within the thylakoid lipid bilayer between LHCII and VDE is required. However, this diffusion is expected to be very slow because macromolecular crowding in grana thylakoids impairs lateral mobility of lipophilic molecules as was shown for PQ (7, 21). Black areas in A indicate the available diffusion space for lipids (6). B and C, Zea induction kinetics for dark-adapted leaves for three different light intensities measured as absorption change at 505 nm (ΔAbs505 nm). The ΔAbs505 nm is normalized to the chlorophyll content. A lag for Zea formation in WT leaves is indicated by the blue arrow. D, initial rates of Zea formation derived from the regression lines in B and C. The data represent mean values of 11 (WT) and 9 (fad5) measurements with standard error.

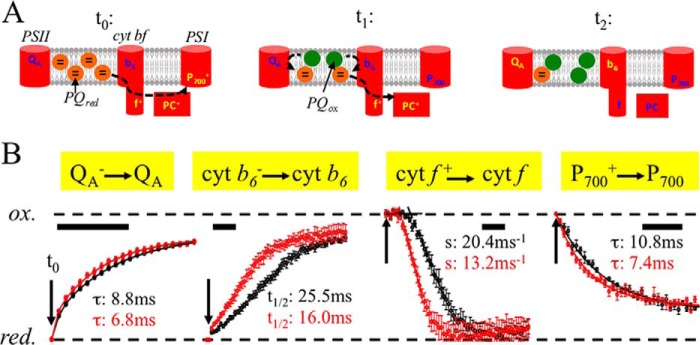

FIGURE 4.

Redox kinetics of PQ reaction partners reveals faster inter-photosystem ET in the fad5 mutant. Freshly isolated chloroplasts were osmotically shocked directly before the measurements leading to highly active thylakoid membranes (linear electron transport rate H2O to MV is 290 μmol O2 (mg of Chl)−1 h−1). Redox changes were induced by a 200-ms saturating light pulse and dark relaxation kinetics measured by difference absorption (cyt f, b6, and P700) or chlorophyll fluorescence (QA) spectroscopy. Conditions are as follows: 100 μm Chl in measuring buffer (pH 8.0), 100 μm MV, 2 μm nigericin, 2 μm valinomycin, and 5 mm sodium ascorbate. A, schematics showing the redox status of the electron transport components at different time points after switching off (t0) the 200-ms saturating light pulse. Note that the first electrons from PQH2 reduce first P700+ (t1). B, normalized redox kinetics; t0 indicates the time point when the light pulse is switched off. Scale bars indicate 10 ms. The data represent four averages collected with three independent biological samples for each genotype. Red circles, fad5 mutant; black circles, WT. Data fitting with exponentials gives time constants (τ) for the QA− re-oxidation. The fitting requires three exponentials. The given time constants are for the dominating (67% amplitude) middle phase that reflects PQ-dependent re-oxidation. P700+ re-reduction kinetics were fitted with two exponentials. The τ values of the main components (74%) are shown in panel B. It was not possible to fit the complex cyt b6− kinetics with exponentials. Therefore, half-times (t½) were deduced. Cyt b6− re-oxidation requires oxidized PQ at the Qr side that is provided by PQH2 turnover at the Qo side and diffusion to the Qr side. For cyt f+ kinetics, regression lines were derived from the point of inflections and extrapolated to 100% reduction that gives the lag times. The lag times for fad5 are 6.2 ms and for WT 10.4 ms. Furthermore, the slopes (s) of the regression lines are indicated. Both the lag phase and the slope of cyt f+ re-reduction depend on diffusion and binding of several PQH2 to the Qo side. The ratios of fad5 to WT for the rates (reciprocal τ and t½) are 1.29 (QA−), 1.46 (P700+), 1.59 (cyt b6−), 1.68 (lag cyt f+), and 1.55 (slope cyt f+). Thus, all PQ-dependent ET reactions are significantly accelerated in fad5. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 4–6 measurements.

In detail, re-oxidation of QA− requires that oxidized PQ binds to the PSII-QB-binding niche. After the light pulse, oxidized PQ is provided by the oxidation of PQH2 at the Qo site of the cyt b6f complex followed by diffusion of PQ from the cyt b6f complex to PSII. Thus, accelerated QA− oxidation is indicative of faster quinone diffusion. Similar to QA−, cyt b6− re-oxidation also needs binding of oxidized PQ at the Qr site. As for QA−, the oxidized PQ is produced by turnover of PQH2 at the Qo site of the cyt b6f complex and subsequent diffusion to the Qr site. Cyt f + shows complex re-reduction with a lag phase. The lag phase is caused by the fact that the electrons from PQH2 first reduce P700+ before PC+ and cyt f + (caused by the more positive redox midpoint potential of the redox pair P700+/P700). Both the lag phase and the subsequent re-reduction kinetics of cyt f + monitor the injection of electrons from Qo-bound PQH2 to cyt f + via the Rieske FeS center. Acceleration of both processes in the fad5 mutant relative to WT supports faster occupation of the Qo site of the cyt b6f complex by PQH2, which is further confirmed by the faster P700+ re-reduction kinetics. Importantly, the observed accelerations of PQ-dependent ET reactions in fad5 are not caused by higher cyt b6f complex concentrations (the rate-limiting enzyme for ET) in thylakoid membranes (see Table 2), supporting the notion that the semi-crystalline protein arrays are the reason why ET reactions are faster. In summary, the faster redox kinetics of the PQ reaction partners in thylakoid membranes of the fad5 mutant is a clear indication of higher mobility of PQ and PQH2, as predicted by the FRAP data (Fig. 3) and the qL parameter (Table 2). Alternatively, a shorter diffusion distance between PSII and cyt b6f complex in disordered grana membranes in the fad5 mutant could explain faster PQ-dependent ET. This possibility is examined in detail under the “Discussion” (under “Two Scenarios That Explain Faster Diffusion of Small Lipophilic Molecules in fad5”).

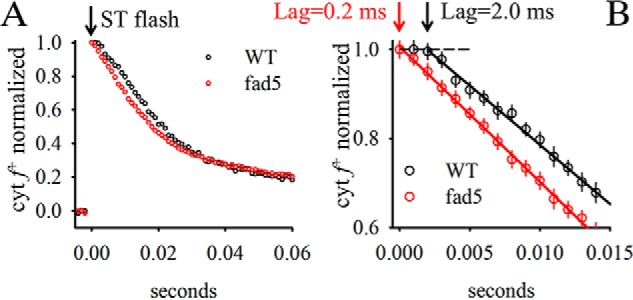

For further characterization of PQH2 diffusion to the cyt f +, single turnover experiments were performed on isolated thylakoid membranes (Fig. 5). For WT thylakoids, cyt f + re-reduction shows a lag phase of about 2 ms. Because under single turnover excitation, cyt f + can only be reduced by PQH2 generated at the QB site (PQ-pool is oxidized). This lag most likely represents the PQH2 diffusion from PSII to cyt b6f complexes. In contrast to WT, this lag is virtually absent in fad5 thylakoids. This indicates facilitated PQH2 diffusion from PSII to cyt b6f complexes in fad5 membranes supporting the conclusion of the previous paragraph.

FIGURE 5.

A, re-reduction kinetics of cyt f+ after single turnover excitation. Same measuring conditions as for Fig. 4. The full width of half-maximum of the flash was 5 μs. B, zoom-in to the time region directly after flash application. Arrows indicate the lag phase derived by extrapolating the reduction kinetics to the complete oxidation level (dashed line). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 10 measurements. Note the difference in lag phase between mutant and WT.

It was reported that the cyt b6f activity is dependent on MGDG (43). To test whether the activity of the cyt b6f complex is affected by the higher saturation level of fatty acids in the fad5 mutant, its turnover number was determined with isolated thylakoid membranes. The turnover number is calculated by dividing the light-saturated cyt b6f-specific electron transport rate by the cyt b6f content determined from difference spectroscopy. The cyt b6f-specific electron transport rates were measured from polarographic oxygen measurements in the presence of the electron donor duroquinol, methyl viologen, and the uncoupler nigericin. Turnover numbers of 173 ± 14 electrons s−1 were measured for WT thylakoid membranes and 172 ± 4 electrons s−1 for the fad5 mutant. It follows that the altered fatty acid composition in fad5 does not cause changes in cyt b6f activity.

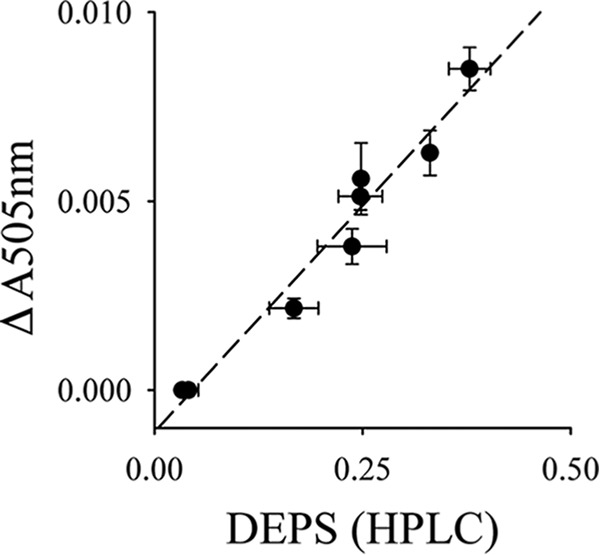

Another process that may be influenced by higher mobility in the lipid bilayer is the conversion of violaxanthin (Vio) to zeaxanthin (Zea) by the xanthophyll cycle. Zea is an important stimulator for NPQ (44–46), a main photoprotective mechanism in plants that minimizes photodamage under high light stress (47, 48). The conversion of Vio to Zea is catalyzed by the enzyme VDE localized in the aqueous thylakoid lumen (44, 49). For the conversion, Vio unbinds from LHCII in grana and diffuses to VDE where it is converted to Zea (Fig. 6A). Zea diffuses back to LHCII and activates NPQ, which safely converts excess excitation energy into heat. To study the diffusion-dependent conversion of Vio to Zea, we measured light-induced Zea formation spectroscopically as absorption changes at 505 nm (ΔA505 nm, see Ref. 50) on intact leaves. We verified by HPLC that ΔA505 nm measures Zea formation (Fig. 7). Fig. 6, B and C, reveals that the kinetics of Zea formation measured at three different light intensities is significantly faster in fad5 leaves. Quantifications of the initial rates of Zea formation (Fig. 6D), deduced from the regression lines in Fig. 6, B and C, show an increase by 140 to 170% for fad5 compared with the WT. This acceleration in Zea formation is neither caused by changes in VDE activity (Table 2) nor by the slight (20%) increase in the xanthophyll pool size (Table 2). It was reported that Vio conversion by VDE requires the nonbilayer HII phase of MGDG (51). Therefore, the lower desaturation level of MGDG in the fad5 mutant could impact Zea formation by altering nonbilayer propensities of MGDG. However, the tendency of MGDG to form HII phases strongly declines with lower desaturation level (52). It follows that the lower fatty acid desaturation level in the fad5 mutant would impair VDE-catalyzed Zea formation in contrast to our measured stimulation. Thus, most likely the higher Zea formation rate is caused by the higher mobility in the lipid bilayer in fad5 thylakoid membranes and not by changes in nonbilayer characteristics of the lipid bilayer.

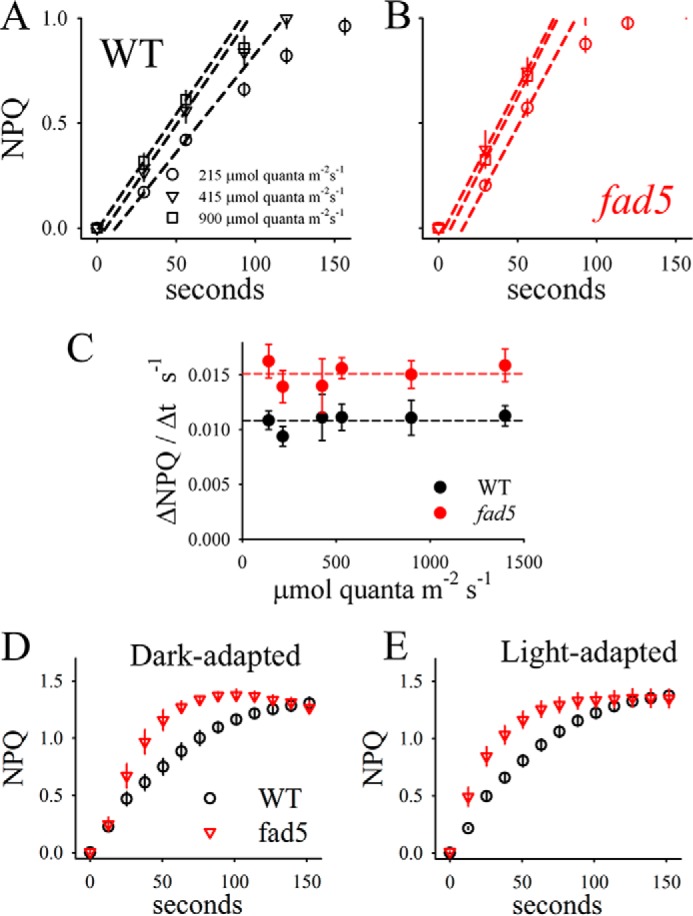

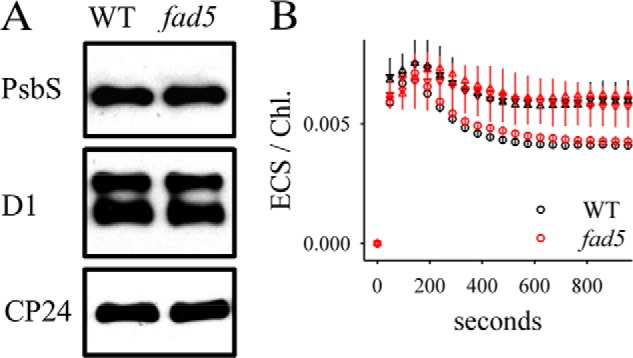

FIGURE 7.

Linear correlation between xanthophyll de-epoxidation levels measured by reverse phase HPLC and absorption change at 505 nm (ΔAbs505 nm) in intact leaves. The different zeaxanthin levels were induced by illumination of WT plants with different light intensities. DEPS, de-epoxidation state.

Because Zea formation is faster in fad5, it is possible that NPQ induction is also accelerated. As illustrated in Fig. 8, NPQ induction kinetics were measured in parallel with the Zea kinetics and reveal acceleration for fad5. The initial rate of NPQ formation is about 40% higher in fad5, independent of the light intensity (Fig. 8C). An accelerated NPQ induction kinetics was also observed in light acclimated plants (compare Fig. 8, D and E). This suggests that these structures also exist in light-adapted plants (assuming that they do not re-form after light-induced dissolving within 30 min of darkness). We checked whether this acceleration is caused by changes in the other two major factors involved in NPQ, the PsbS protein (53) and the pmf across the thylakoid membrane (48). Both the PsbS level as well as the pmf are indistinguishable in fad5 and WT (Fig. 9). Overall, the functional studies on photosynthetic processes that depend on the mobility of small hydrophobic molecules (PQ, xanthophylls) show that protein ordering in grana accelerates these processes most likely by faster diffusion. Although semicrystalline arrays are advantageous for the mobility of small molecules, their impact on larger components like protein complexes turned out to be different, as examined below.

FIGURE 8.

Accelerated NPQ induction in fad5 mutant. NPQ induction was measured on identical samples in parallel to the Zea kinetics (Fig. 6). A and B, examples of NPQ induction for three different light intensities. The initial rates are determined by regression lines (dashed lines). C, initial rates of NPQ induction as a function of light intensity. On average, the rates are 40% higher in fad5 mutants compared with WT plants. The data represent mean values of 11 (WT) and 9 (fad5) measurements with standard error. Kinetics of NPQ induction for dark-adapted (D) and light-adapted (E) leaves are shown.

FIGURE 9.

Immunoblot (A) and ECS (B) analysis. A, immunoblot analysis of PsbS, CP24, and D1 proteins was performed with protoplasts isolated from WT and fad5 plants. B, ECS detected as absorption change at 520 nm was measured in parallel to the NPQ and zeaxanthin kinetics on intact Arabidopsis leaves (Figs. 5 and 6). The absorption signals were divided by the Chl content per leaf area to correct for different Chl contents. Circles, 215 μmol quanta m−2 s−1; triangles, 900 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. ECS, electrochromic shift.

Implications of Semicrystalline Array Formation for Protein Repair

A central protein repair mechanism in plants is the PSII repair cycle, which is one of the fastest protein turnover processes in nature (16). Repair of PSII is necessitated by the fact that among the different protein complexes in thylakoid membranes, PSII is the main target of photooxidative damage (54). Within the massive C2S2M2 PSII holocomplex (Fig. 1C), the central D1 subunit is mainly vulnerable to damage (54) and has to be replaced by a newly synthesized copy to maintain photosynthetic efficiency. Before the new D1 subunit can be inserted, PSII has to migrate from the grana to the stroma lamellae, and the damaged subunit has to be degraded by specific proteases (55, 56). After repair, the restored PSII reassembles into the holocomplex and diffuses back into the grana, which completes the repair cycle. Thus, the PSII repair cycle depends on efficient protein traffic between stacked grana thylakoids where damage occurs and unstacked stroma lamellae where the repair machinery is localized (18). We examined whether the diffusion-dependent PSII repair is influenced by semicrystalline array formation in the fad5 mutant.

In a first set of experiments, intact plants were monitored from the juvenile to the mature developmental stage. This long term experiment was performed in the Phenomics Facility at Washington State University that allows automated, noninvasive, and repetitive observation of the chlorophyll fluorescence qI parameter, which is a measure of PSII photoinhibition (57). Recently, it has been suggested that qI is heterogeneous, containing components other than the one that indicates damage to PSII (58). However, the higher photoinhibitory qI in the fad5 mutant is in agreement with a slower D1 degradation, as detailed below. Thus, a combination of increased qI parameter and slower D1 degradation in fad5 is strongly suggestive of an increased photoinhibition in the mutant. False color images for qI of mature dark-adapted plants in Fig. 10A show a clear increase in qI for the fad5 mutant plants compared with WT plants. Statistical analysis over the 17-day measuring period in the phenomics greenhouse reveals, on average, a 37% increase in the qI parameter in fad5 mutants relative to WT plants indicating that the PSII repair cycle is impaired in agreement with previous studies (59). This was further analyzed with isolated protoplasts (Fig. 10C). Illumination with strong white light over 1 h to induce PSII photodamage causes significantly more inhibition in fad5 protoplasts (higher qI in Fig. 10C), in accordance with the phenomics data. The stronger photoinhibition in fad5 can be explained by a drastically reduced mobility of PSII localized in semicrystalline protein arrays, because the 1–2-nm gap (5) between rows in the arrays prevents diffusion of LHCII trimers (diameter ∼7.5 nm, Ref. 60) or monomeric PSII-cores (∼9 nm, Ref. 61) (see also Fig. 1C). It is expected that PSII complexes that are damaged in crystalline arrays will be degraded more slowly because they cannot efficiently escape to reach the proteases in distant unstacked thylakoid regions. To test this, we measured D1 degradation in the presence of the plastidial protein synthesis inhibitor lincomycin. Lincomycin prevents the synthesis of nascent D1 (62) allowing the monitoring of the net degradation of this subunit. Western blot analysis (Fig. 10D) demonstrates that after 15, 30, 60, and 120 min of high light treatment, less D1 is degraded in fad5 than in WT leaves. Analysis of this extended time series confirms that retarded D1 degradation is apparent for shorter as well as longer HL treatments (Fig. 10D). The use of a dilution series for the D1 reveals that our quantification is in the linear detection range of the Western blot analysis (Fig. 10D).

The degradation of D1 depends on FtsH proteases (55) and the phosphorylation of PSII-core subunits (63, 64). For FtsH, it was also postulated that its oligomerization state can influence its proteolytic activity (65). To examine whether the mutant has any aberrant protease or phosphorylation levels that might explain its delayed D1 degradation, Western blot analysis with FtsH and phosphothreonine antibodies was performed (Fig. 10, E and F). The level of FtsH was slightly increased in the fad5 mutant compared with WT (Fig. 10E), indicating a possible compensatory response in the mutant to the impaired D1 degradation. It thus follows that changes in FtsH level cannot explain the slower D1 degradation in fad5 (the D1 level should, in fact, go down more extensively, given the increased FtsH level). Similarly, the dark and HL phosphorylation levels of PSII-core subunits (D1, D2, and CP43) is indistinguishable in both genotypes (Fig. 10E). Thus, an altered PSII-core phosphorylation behavior in the fad5 mutant cannot also be the reason for its slower D1 breakdown. These studies support the notion that impaired mobilization of damaged PSII in grana thylakoids by semicrystalline arrays inhibits efficient D1 degradation and initiation of the repair cycle. However, an alternative possibility is that steps in PSII degradation could be affected by the altered fatty acid composition in fad5.

Protein Densities and Compositions in Disordered Grana

At first sight, the retarded mobilization of damaged PSII in the fad5 mutant contradicts the FRAP data that showed higher protein mobility in fad5 thylakoid membranes (Fig. 3). However, we have to consider that only 50% of grana membranes are in a semicrystalline state in fad5, whereas the rest are disordered (Fig. 1). FRAP analysis integrates over both regions and reflects the overall protein mobility (Fig. 3E). Assuming that the protein mobility in semicrystalline arrays is zero, then the mobile fraction (fraction that recovers in FRAP experiments) in disordered grana regions can be calculated as 21% for the WT (18% mobile fraction from FRAP/0.86 fraction of disordered grana) and 56% for fad5 (28%/0.5). To understand the 2.7 times higher mobile fraction in disordered grana in fad5 relative to the WT, knowledge about the protein compositions and densities in this membrane region is required.

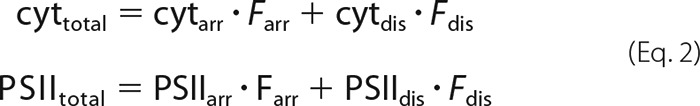

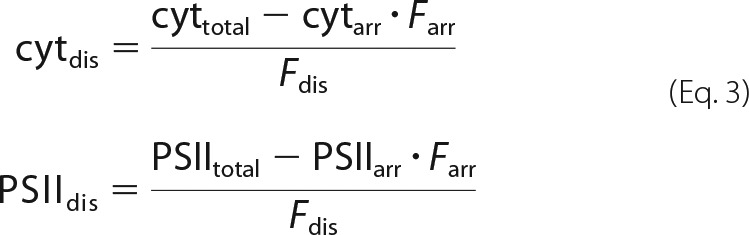

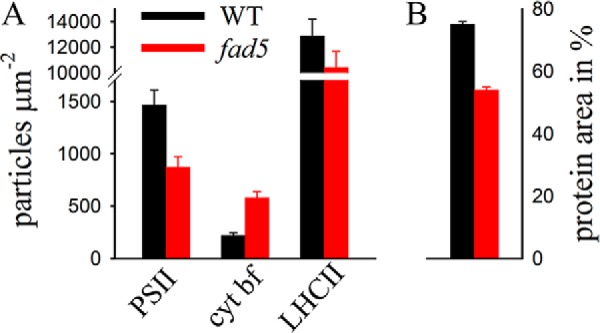

The quantitative analysis of AFM data combined with protein quantifications in Table 2 allows calculation of the protein compositions and densities in disordered grana. In the first step, the concentrations of PSII, cyt b6f complex, and LHCII trimers are calculated for the disordered grana (abbreviated as PSIIdis, cytdis, and LHCIIdis). In the second step, this information is used to calculate particle densities and protein area fractions for disordered grana thylakoids. The measured total PSII (PSIItotal) and cyt b6f complex (cyttotal) concentrations in grana shown in Table 2 (including semicrystalline and disordered grana) is given by weighted concentrations of the complexes in both membrane types. The weighing factor is the fraction of arrayed (Farr) and disordered (Fdis = 1 − Farr) grana derived from AFM analysis (Farr = 0.16 for WT and 0.5 for fad5). As shown in Equation 2,

|

Rearranging these equations leads to protein concentrations in disordered grana as shown in Equation 3,

|

From the fact that semicrystalline arrays in grana contain C2S2M2 supercomplexes and no cyt b6f complex, it follows that cytarr = 0 and PSIIarr = 6.803 mmol of PSII/mol of Chl. The latter number is derived from published data giving that each PSII monomer in a C2S2M2 complex binds 147 Chls (23). From Eq. 3 and the concentration data in Table 2, the concentration for cyt b6f complexes in disordered grana is calculated to 0.525 mmol of cyt b6f/mol of Chl in WT and 0.946 mmol of cyt b6f/mol of Chl in fad5. For PSII, the numbers are 3.543 mmol of PSII/mol of Chl in WT and 1.393 mmol of PSII/mol of Chl in fad5.

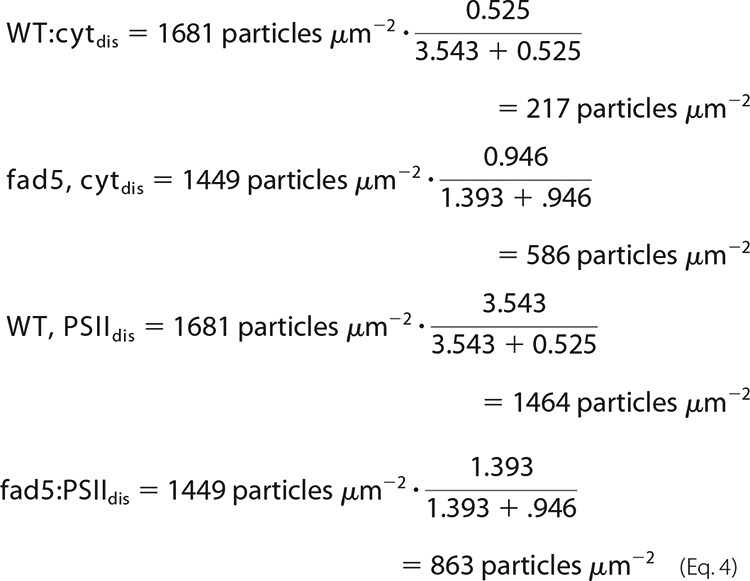

These numbers can be converted into particle densities by using the total particle densities in disordered grana derived from AFM (1449 particles μm−2 for fad5 and 1681 particles μm−2 for WT) as shown in Equation 4,

|

An important outcome of these quantitative considerations is that the PSII density in disordered grana of fad5 plants decreases by about 40%. At the same time, the PSII/cyt b6f complex ratio drops from 6.7 in WT to 1.5 in fad5.

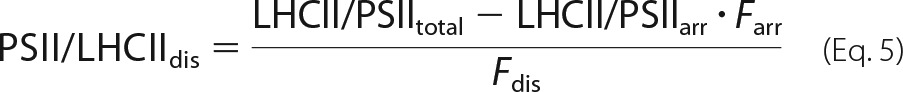

To complement the protein analysis for disordered grana, the density of LHCII trimers (abbreviated as just LHCII in the following sections) have to be added. This is derived from the PSII particle densities (see above) and the LHCII/PSII ratios. The LHCII/PSII ratio in disordered grana (LHCII/PSIIdis) is calculated similarly as in Eq. 3 and as shown in Equation 5,

|

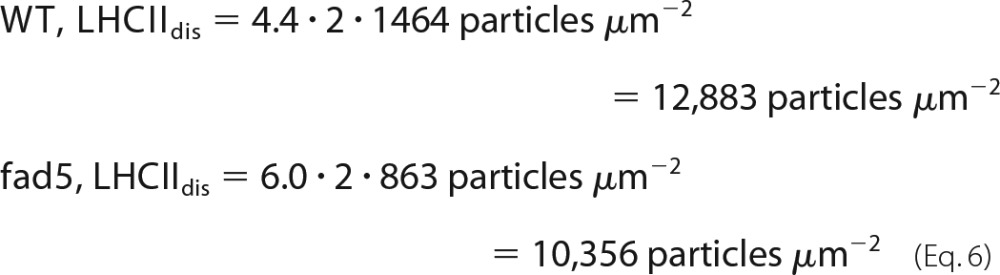

LHCII/PSIItotal for grana from both genotypes is 4.0 (Table 2) and from the C2S2M2 organization in semicrystalline arrays it follows that LHCII/PSIIarr is 2.0. Eq. 5 gives LHCII/PSIIdis of 4.4 for the WT and 6.0 for fad5 mutant. The LHCII particle density of trimeric LHCII is calculated by multiplication of the LHCII/PSII ratios with the PSII densities (Eq. 4) as shown in Equation 6,

|

The factor of 2 has to be introduced because each PSII-AFM particle represents a dimer (35). The particle densities in disordered grana are visualized in Fig. 11. LHCII can be either part of the C2S2M2 supercomplex or can be free (LHCIIfree). The free LHCII trimers are given by Equation 7,

|

The factor of 4 results from the fact that each PSII-AFM particle binds four LHCII trimers.

FIGURE 11.

Particle densities and protein composition in disordered grana. Quantitative analysis of protein complex concentrations combined with AFM data was used to estimate the particle densities of the PSII supercomplex, LHCII, and cyt b6f complexes in disordered grana thylakoid membranes for WT (black) and fad5 mutant (red). From the data, the relative protein area was calculated (right). Error bars indicate standard error.

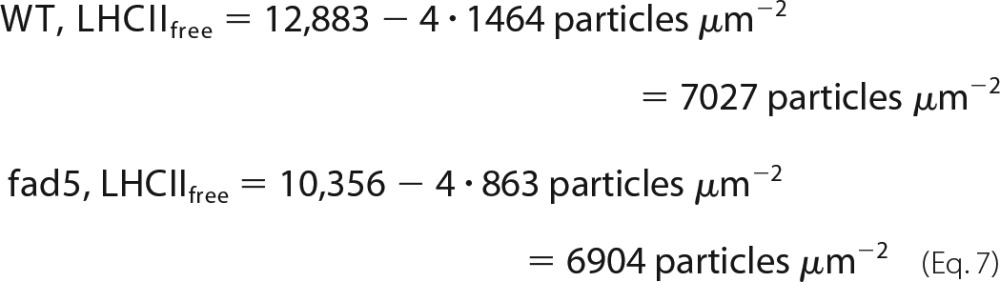

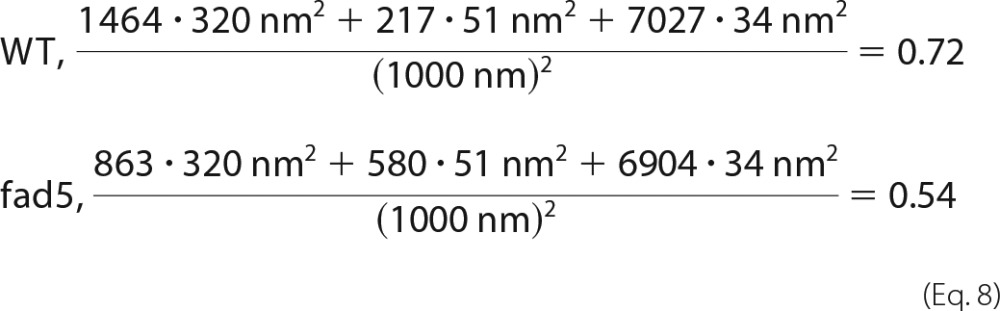

Based on this detailed knowledge of protein densities, it is finally possible to estimate the membrane area fraction covered by proteins in disordered grana thylakoids. The molecular areas for the three protein complexes were taken from Ref. 21. For the PSII supercomplex, the molecular area is 320 nm2; for dimeric cyt b6f complexes is 51 nm2, and for trimeric LHCII 34 nm2. Therefore, the relative protein area fractions in WT and fad5 disordered grana are shown in Equation 8,

|

These quantitative estimations reveal that the relative protein occupied area in disordered grana drops from 72% in WT to 54% in fad5 (Fig. 11).

Discussion

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that protein array formation facilitates lateral diffusion in crowded photosynthetic membranes (6). Toward meeting this objective, we established the fatty acid desaturase fad5 Arabidopsis mutant as a model system that forms the same type of semicrystalline arrays as WT plants but retains the thylakoid membrane composition as their WT counterpart.

By applying FRAP to monitor diffusion in thylakoid membranes, we can demonstrate that supramolecular reorganization into the semicrystalline state increases the overall mobility of both small lipophilic molecules in the membrane lipid bilayer and of protein complexes (Fig. 3). The accelerated diffusion of lipid-like molecules has a direct physiological impact for PQ-dependent ET reactions and for induction of photoprotective NPQ (Figs. 4, 6, and 8). In contrast, as shown by the comparison of PSII repair efficiencies in fad5 and WT plants, semicrystalline array formation significantly impairs the mobility of damaged PSII (Fig. 10). It follows that changing the protein organization into a more ordered state has advantages for the mobility of small molecules like PQ or xanthophylls but has disadvantages for diffusion of larger molecules like PSII if they are localized in the arrays. Thus, it turns out that the original hypothesis must be modified in such a way that semicrystalline array formation in plant photosynthetic membranes has a differential impact on the mobility depending on the size and localization of the particles of interest.

Because our structural studies on the fad5 mutant and WT were done on dark-adapted samples an open question is whether protein crystals in thylakoid membranes exist in light-acclimated plants as well, whether they dissolve, and how fast they dissolve. Evidence exists that the supramolecular protein arrangement in disordered grana thylakoids is dynamic and changes in response to environmental factors (13, 14). Thus, there is a probability that protein crystals dissolve in the light. Because no reliable methods exist to study the abundance of PSII arrays in light-adapted states, this question has to be addressed in the future after adequate methods are available. However, there are several lines of evidence indicating that the PSII arrays in thylakoid membranes are more stable. (i) In other mutants (ko-CP24 and viridis zb63, see under “Comparison with Other Mutants”) functional phenotypes related to semicrystalline PSII arrays are still visible in light adapted plants. (ii) In structural studies on the formation of semicrystalline arrays triggered by low temperatures (66, 67), a long incubation time is required (many hours or even days). Thus, at least the crystal formation seems to be a slow process. (iii) In our study (and in Ref. 38), we measured functional differences for light-treated plants (NPQ and Zea formation and PSII photoinhibition) demonstrating that photosynthetic machinery in the light behaves differently in fad5, although the membrane composition is very similar to WT (Table 2). Although there is no hard evidence, they all point to a stability of semicrystalline arrays in light-treated fad5 samples.

Higher Protein Mobility in the fad5 Mutant Is Caused by Structural Alterations in Disordered Grana Thylakoids

As pointed out under “Results,” the higher overall protein mobility in fad5 is most likely due to the significant lower protein density in disordered grana (Fig. 11). Monte Carlo computer simulations (9) predict that a drop in protein area occupancy from 72% (WT) to 54% (fad5) has a huge impact on the overall protein mobility. The computer simulation shows that between 60 and 70% protein area, a percolation threshold (cP) exists. If the protein density is above cP, long range protein diffusion is no longer possible. If the density is below cP, long range diffusion is possible. This threshold characteristic for protein mobility in grana is supported by FRAP measurements on “diluted” isolated grana thylakoids (10). The crucial point is that small changes (a few 10%) in protein packing density around cP have significant impact on protein mobility (68). The drop to 54% protein area in disordered grana in fad5 brings the system to below cP and allows much higher protein mobility compared with the WT. The higher protein mobility in disordered grana can support the faster induction of NPQ (Fig. 8), because evidence exists that diffusion-dependent reorganization of the PSII antenna system in stacked grana membranes is involved in this photoprotective mechanism (13, 14). In these studies, it was proposed that part of the LHCII decouples from PSII and migrates to separated grana areas where they form quenching aggregates (quenched LHCII supercomplex). It is likely that these rearrangements in grana thylakoids are facilitated in disordered fad5 grana because of the higher protein mobility. An open question is how PSII/LHCII supercomplexes are photoprotected in semicrystalline arrays because in these membrane areas large scale re-arrangements of proteins are very difficult. Therefore, a second photoprotective mechanism could be realized for C2S2M2 supercomplexes in arrayed regions. There is evidence that besides the formation of quenched LHCII supercomplexes an independent second quenching process exists localized in C2S2M2 (69). As for the energy quenching in LHCII supercomplexes, photoprotective energy dissipation into heat in C2S2M2 is also Zea-dependent (69). In this respect, the small lipidic gap between PSII-LHCII rows postulated from EM tomographic data (5) could ensure exchange of xanthophylls between C2S2M2 localized in semicrystalline protein arrays and VDE to induce Zea-dependent photoprotective quenching. An alternative explanation is that due to a high excitonic connectivity between C2S2M2 supercomplexes in semicrystalline arrays, the binding of quenchers at the crystal periphery could be sufficient for photoprotection.

Two Scenarios That Explain Faster Diffusion of Small Lipophilic Molecules in fad5

In contrast to the large protein complexes where the higher mobility in fad5 can be pinpointed to disordered grana, the faster diffusion of lipid-like molecules can have two reasons. As mentioned above, one possibility is that diffusion of lipid-like molecules can be improved by formation of small lipid-filled diffusion channels between protein rows in the semicrystalline grana domains. This channel would not only be important for xanthophyll exchange (see above) but also for electronic connection between PSII in semicrystalline arrays and cyt b6f complexes localized outside these arrays. As the protein arrays are extended (see Fig. 1), PQ must travel over a few 100 nm to reach cyt b6f complexes that do not fit into the array architecture (Fig. 1). The fact that the reduction level of the PQ-pool is even lower in the fad5 mutant compared with WT (qL parameter in Table 2) indicates an efficient PQ diffusion between the PSII rows in semicrystalline arrays. A second possibility is that PQ diffuses faster in less crowded disordered grana in the mutant, which also explains accelerated kinetics of PQ-dependent ET reactions (Fig. 4). However, the fact that other mutants with semicrystalline PSII arrays but different crystal architecture show a very different behavior concerning PQ mobility suggests that the more efficient diffusion of lipid-like molecules between PSII rows in the arrays could be the main factor for the higher mobility in fad5. This is addressed below.

Comparison with Other Mutants

It was reported that some other mutants also show higher abundances of semicrystalline protein arrays in grana thylakoid membranes. Although the abundance of arrays in the Arabidopsis ko-PsbS (npq4 mutant) and the ko-CP26 mutants increases only marginally (8, 70), a significant fraction of grana membranes is in the arrayed state in the ko-CP24 mutant (71) and the barley viridis zb64 mutant (72). Although the abundance of protein arrays in the latter two mutants is high, their functional consequences are very different compared with the fad5 mutant. In detail, compared with WT plants, the ko-CP24 and viridids zb63 mutants have lower linear electron flow, lower ΔpH and NPQ, and have strongly impaired PQ diffusion (71, 72). Furthermore, state transitions are impaired indicating retarded diffusion of LHCII (71). The very different phenotypes of the ko-CP24 and viridis zb63, compared with the fad5 mutant, are caused by different protein crystal geometries (lattice constants). This in turn is caused by the prevalence of C2S2 supercomplexes in ko-CP24 and viridis zb63, as opposed to C2S2M2 complexes in WT and fad5 (8, 73). This different crystal architecture in ko-CP24 and viridis zb63 blocks access of PQ and xanthophylls to PSII in semicrystalline arrays, which causes their severe phenotypes. The comparison between these mutants and fad5 reveals that the exact type of PSII supercomplexes and the resulting difference in protein array structure are essential for understanding their functional implications.

Physiological Consequences of Protein Array Formation in Grana Thylakoids

The mixed consequences of semicrystalline protein arrays have interesting physiological implications because changes in the supramolecular order can favor either diffusion-dependent ET and NPQ or the PSII repair cycle. In this respect, it is understandable that abiotic factors like temperature, light, or osmotic potential trigger the re-arrangement in grana thylakoids because it allows the fine-tuning of different photosynthetic processes to different requirements dictated by environmental cues. For the same reason, protein arrays do not exist in high light conditions (74), where the PSII repair has an overriding functional importance for the survival of the plant.

In summary, our work demonstrates that the degree of ordering in thylakoid membranes affects the mobility of membrane constituents and consequently membrane functions. An intriguing question is what factors govern supramolecular changes. A favorite candidate for the photosynthetic membrane is the PsbS protein (53) because overexpression or knocking out this membrane-integral protein either decreases or increases the abundance of semicrystalline arrays (70). However, the observation that simple cold incubation of isolated thylakoid membranes with exactly the same composition can induce semicrystalline array formation in grana (66) points to the possibility that other factors are involved as well. In this respect, it is noteworthy that rearrangement to the semicrystalline state is often accompanied by changes in lipid/fatty acid properties (as studied here for the fad5 mutant). Therefore, lipid/fatty acid-induced changes of physicochemical properties of the lipid bilayer could play a central role in controlling protein organization in photosynthetic membranes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. John Browse (Washington State University) for the kind gift of Arabidopsis fad5 mutant seeds and for help with fatty acid analysis.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB115871 (to H. K.), United States-Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund US-4334-10, United States Department of Agriculture ARC Grant WNP00775, and Washington State University. The immunoblot experiments were supported by a grant from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, United States Department of Energy, FWP number SISGRKN (to K.K.N.)

- ET

- electron transport

- PS

- photosystem

- LHC

- light-harvesting complex

- PQ

- photochemical quenching

- NPQ

- nonphotochemical quenching

- AFM

- atomic force microscopy

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy

- MV

- methyl viologen

- Chl

- chlorophyll

- pmf

- protonmotive force

- cyt

- cytochrome

- VDE

- violaxanthin-de-epoxidase

- Vio

- violaxanthin

- Zea

- zeaxanthin

- MGDG

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol

- DCMU

- 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

- HL

- high light.

References

- 1. Engelman D. M. (2005) Membranes are more mosaic than fluid. Nature 438, 578–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nelson N., Ben-Shem A. (2004) The complex architecture of oxygenic photosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dekker J. P., Boekema E. J. (2005) Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 12–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park R. B., Biggins J. (1964) Quantasome: Size and composition. Science 144, 1009–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daum B., Nicastro D., Austin J., 2nd, McIntosh J. R., Kühlbrandt W. (2010) Arrangement of photosystem II and ATP synthase in chloroplast membranes of spinach and pea. Plant Cell 22, 1299–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchhoff H. (2008) Molecular crowding and order in photosynthetic membranes. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirchhoff H., Horstmann S., Weis E. (2000) Control of the photosynthetic electron transport by PQ diffusion microdomains in thylakoids of higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459, 148–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goral T. K., Johnson M. P., Duffy C. D., Brain A. P., Ruban A. V., Mullineaux C. W. (2012) Light-harvesting antenna composition controls the macrostructure and dynamics of thylakoid membranes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 69, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tremmel I. G., Kirchhoff H., Weis E., Farquhar G. D. (2003) Dependence of the plastoquinone diffusion coefficient on the shape, size, density of integral thylakoid proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1607, 97–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirchhoff H., Haferkamp S., Allen J. F., Epstein D. B., Mullineaux C. W. (2008) Significance of macromolecular crowding for protein diffusion in thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 146, 1571–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goral T. K., Johnson M. P., Brain A. P., Kirchhoff H., Ruban A. V., Mullineaux C. W. (2010) Visualizing the mobility and distribution of chlorophyll proteins in higher plant thylakoid membranes: effects of photoinhibition and protein phosphorylation. Plant J. 62, 948–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen J. F. (1992) Protein phosphorylation in regulation of photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1098, 275–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Betterle N., Ballottari M., Zorzan S., de Bianchi S., Cazzaniga S., Dall'osto L., Morosinotto T., Bassi R. (2009) Light-induced dissociation of an antenna hetero-oligomer is needed for non-photochemical quenching induction. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15255–15266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson M. P., Goral T. K., Duffy C. D., Brain A. P., Mullineaux C. W., Ruban A. V. (2011) Photoprotective energy dissipation involves the reorganization of photosystem II light-harvesting complexes in the grana membranes of spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell 23, 1468–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kyle D. J., Ohad I., Arntzen C. J. (1984) Membrane protein damage and repair: selective loss of quinone-protein function in chloroplast membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 181, 4070–4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Melis A. (1999) Photosystem-II damage and repair cycle in chloroplasts: what modulates the rate of photodamage in vivo? Trends Plant Sci. 4, 130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulo P., Sirpiö S., Suorsa M., Aro E. M. (2008) Auxiliary proteins involved in the assembly and sustenance of photosystem II. Photosyn. Res. 98, 489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirchhoff H. (2013) Structural constraints for protein repair in plant photosynthetic membranes. Plant Signal. Behav. 8, e23634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Porra R. J., Thompson W. A., Kriedemann P. E. (1989) Determination of accurate extinction coefficient and simultaneous equations for essaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975, 384–394 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Izawa S., Pan R. L. (1978) Photosystem I electron transport and phosphorylation supported by electron donation to the plastoquinone region. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 83, 1171–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirchhoff H., Mukherjee U., Galla H. J. (2002) Molecular architecture of the thylakoid membrane: lipid diffusion space for plastoquinone. Biochemistry 41, 4872–4882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirchhoff H., Schöttler M. A., Maurer J., Weis E. (2004) Plastocyanin redox kinetics in chloroplasts: Evidence for a dis-equilibrium in the high potential chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1659, 63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]