Background: Kunitz-type inhibitors provide a suitable scaffold for novel elastase inhibitors.

Results: The inhibitor ShPI-1 was modified for pancreatic elastase binding, and the crystal structure of the complex was elucidated and analyzed.

Conclusion: The extended protease-inhibitor interactions provide a potential switch to direct inhibitor selectivity toward elastases.

Significance: These results will help to design novel elastase inhibitors for the treatment of tissue destruction diseases.

Keywords: crystal structure, protease inhibitor, protein complex, serine protease, site-directed mutagenesis, BPTI-Kunitz type

Abstract

Elastase-like enzymes are involved in important diseases such as acute pancreatitis, chronic inflammatory lung diseases, and cancer. Structural insights into their interaction with specific inhibitors will contribute to the development of novel anti-elastase compounds that resist rapid oxidation and proteolysis. Proteinaceous Kunitz-type inhibitors homologous to the bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) provide a suitable scaffold, but the structural aspects of their interaction with elastase-like enzymes have not been elucidated. Here, we increased the selectivity of ShPI-1, a versatile serine protease inhibitor from the sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus with high biomedical and biotechnological potential, toward elastase-like enzymes by substitution of the P1 residue (Lys13) with leucine. The variant (rShPI-1/K13L) exhibits a novel anti-porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE) activity together with a significantly improved inhibition of human neuthrophil elastase and chymotrypsin. The crystal structure of the PPE·rShPI-1/K13L complex determined at 2.0 Å resolution provided the first details of the canonical interaction between a BPTI-Kunitz-type domain and elastase-like enzymes. In addition to the essential impact of the variant P1 residue for complex stability, the interface is improved by increased contributions of the primary and secondary binding loop as compared with similar trypsin and chymotrypsin complexes. A comparison of the interaction network with elastase complexes of canonical inhibitors from the chelonian in family supports a key role of the P3 site in ShPI-1 in directing its selectivity against pancreatic and neutrophil elastases. Our results provide the structural basis for site-specific mutagenesis to further improve the binding affinity and/or direct the selectivity of BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitors toward elastase-like enzymes.

Introduction

Elastases represent highly specific serine proteases that catalyze the cleavage of fibrous elastin, a connective tissue protein that causes tissue shape reconstruction after stretching and contradiction, as well as other extracellular matrix proteins (1). Elastin is particularly abundant in the lungs but is also present in arteries, skin, and ligaments. Consequently, abnormal elastolytic activities are considered to play important roles in tissue destruction associated with several diseases (2–5, 7–10). Under normal physiological conditions, human neuthrophil elastase (HNE)2 is tightly controlled by its endogenous inhibitors. However, their HNE affinity is strongly decreased by oxidative stress and by proteases released from leukocytes that are recruited to inflammation sites (5). Synthetic elastase inhibitors have been tested without satisfactory results (3, 7), highlighting the need to identify or to develop novel anti-elastase molecules that resist rapid oxidation and proteolysis to control elastase-associated diseases.

The molecular mechanisms of HNE activity are well understood, but structural data on its specific inhibition by other proteins are limited, largely because of protein glycosylation and release of a series of isoenzymes (11). Solely HNE complexes with two canonical inhibitors, the C-terminal domain of SLPI (1/2SLPI) (12) and the Kazal-type inhibitor OMTKY3 (13), have been reported. For the natively non-glycosylated porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE), x-ray structures have been solved in complex with three canonical inhibitors, namely elafin from the chelonian family (14), the Ascaris-type inhibitor C/E-1 (15), and a hybrid molecule (HEI-TOE) in which the binding loop of the squash-type inhibitor from Ecballium elaterium was substituted by a sequence derived from the third domain of the Kazal-type turkey ovomucoid inhibitor (16).

Among the canonical inhibitors of serine proteases, the BPTI-Kunitz family (PFAM PF00014) represents one of the most studied, particularly its prototypical member BPTI (17–19). BPTI-Kunitz inhibitors usually contain a basic residue at the reactive site, denoted as P1 position by Schechter and Berger (20). Thus, they strongly inhibit trypsin-like enzymes, but also chymotrypsin and HNE, with comparatively lower affinity. In contrast, the interaction with PPE is usually very weak or not observed at all (18, 21). This elastase specificity could be attributed to a more flexible S1 pocket in HNE that allows accommodation of a broad variety of P1 residues (11, 22–24). Supporting this concept, the substitution at P1 position with amino acids characterized by medium-sized hydrophobic side chains, such as Val, Ala, and Leu, not only increases the affinity of BPTI for HNE (25–27) but also converts it into a tight-binding inhibitor of pancreatic elastase with Ki values around 10−9 m. Affinity selection of a phage-displayed library of BPTI variants against PPE reveals an almost exclusive preference for Leu at the P1 position (28). Selectivity toward HNE or PPE is also described for other canonical inhibitor families, additionally indicating the importance of further subsites other than P1 for the elastase interaction (12).

The stability and experimental tractability of BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitors have favored their exploration among canonical inhibitors as a scaffold for the development of protein therapeutics targeting different serine proteases (29–31). Although the structural details of trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibition by BPTI have been extensively investigated (32–35), the structural basis of the elastase specificity has not been elucidated for this type of inhibitors. Together with the large number of available mutagenesis studies (25–28), structural insights into the elastase interaction could provide important information for the design of novel potent elastase inhibitors exploiting the Kunitz-type scaffold.

We reported previously the isolation as well as functional and structural characterization of the BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitor ShPI-1 from the Caribbean sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus (UniProt accession number P31713) (21, 36). This molecule inhibits not only serine proteases but also cysteine and aspartic proteases such as papain and pepsin with Ki values in the nanomolar range (21), qualifying ShPI-1 for biotechnological use (37). We recently presented the three-dimensional structure of free and trypsin-bound recombinant ShPI-1 (rShPI-1A) (35, 38), revealing a high degree of conservation for the intermolecular interactions around the basic P1 residue (Lys13) compared with homologous complexes of mammalian inhibitors. However, a prominent stabilizing role of arginine at the P3 position was identified as the most significant deviation, thus far unique within this inhibitor family.

Obtaining new variants of ShPI-1 will increase its biomedical and biotechnological capabilities. Thus, we report here its transformation into a specific pancreatic elastase inhibitor. Although the site-directed K13L replacement also maintains the inhibitory activity against chymotrypsin and HNE, trypsin inhibition is significantly reduced. The crystal structure of rShPI-1/K13L in complex with PPE determined at 2.0 Å resolution allowed the detailed investigation of the first example of a BPTI-Kunitz inhibitor/elastase interaction. Compared with the trypsin and chymotrypsin complexes of rShPI-1A, the interface with PPE is improved by increased contributions of the primary inhibitor binding loop and of glycine residues close to the secondary binding loop. A comparison with other canonical inhibitors in complex with HNE and PPE revealed that the side chain of Arg11 at the P3 site of ShPI-1/K13L extends into the same enzyme region as the P5 residue of chelonians, which is reported to direct the elastase selectivity of these inhibitors (12). Thus, the P3 site of ShPI-1/K13L represents a potential candidate for modifying its activity against HNE or PPE. Supporting a previous report of a BPTI variant, our structural results will significantly contribute to selectivity modifications of BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitors toward these enzymes in the future.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning and Production of ShPI-1/K13L

The gene of ShPI-1A was amplified by PCR with site-specific primers using the plasmid pBM301 as a template; it was obtained previously for rShPI-1A expression (37). The purified product was cloned into the XhoI/XbaI-digested pPICZαA vector (Invitrogen). The mutation K13L was introduced according to the QuikChange® II XL protocol (Stratagene) using the mutagenic primers 5′-TCGGCCGTTGCCTAGGTTACTTCCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGAAGTAACCTAGGCAACGGCCGA-3′ (antisense). These primers carried the desired mutations (underlined) and an XmaJI (AvrII) restriction site (C↓CTAG) for detection of positive clones. The variant protein was produced, purified, and stored following the previously established protocol for recombinant wild-type rShPI-1A (37). Protein production and purification was followed by SDS-PAGE (39). Inhibitory activity was determined by measuring the residual activity of pancreatic chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1) at 25 °C with Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA as a substrate (40). The identity of rShPI-1/K13L was verified by molecular mass determination applying MALDI-TOF MS (Biflex spectrometer, Bruker Daltonics) using α-cyano-4-hydroxicinnamic acid as a matrix.

Specificity Studies and Determination of the Equilibrium Dissociation Constants (Ki)

The enzyme specificity of the rShPI-1/K13L inhibitor was determined using the serine proteases trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4, Sigma), HNE (EC 3.4.21.37), PPE (EC 3.4.21.36), and Bacillus licheniformis subtilisin A (EC 3.4.21.62), all from Calbiochem-Novabiochem. After incubation with rShPI-1/K13L for 10–30 min at 25 °C, residual enzymatic activities were measured by monitoring the cleavage of the specific substrates Bz-Arg-pN (for trypsin (41)) and MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA (for HNE (42)), both of which are from Calbiochem-Novabiochem, as well as Suc-Ala-Ala-Ala-pNA from Sigma (for PPE (42) and Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA from Bachem (for subtilisin A (43)) .

The active concentration of rShPI-1/K13L was determined using a constant active concentration of chymotrypsin, previously titrated with soybean trypsin inhibitor. The latter was titrated with a known active concentration of trypsin that was determined previously (44). All experiments were performed under titration conditions (Eo/Ki ≥ 100). The formation of equimolar enzyme-inhibitor complexes was consistently assumed. Apparent inhibition constants (Ki app) were determined as described (45), by fitting the steady state velocities to the equation for tight-binding inhibitors (46). Nonlinear regression analysis was performed using GraFit v.3.01 (47). Real Ki values were calculated using the equation Ki = Ki app/([S0]/(Km) + 1), considering the substrate concentration [S0] and their reported Km values (40–42). Inhibitory activities were additionally determined at different incubation times and substrate concentrations.

Complex Formation and Crystallization

The binary complex rShPI-1/K13L·PPE was formed by incubating PPE with a 2-fold molar inhibitor excess in 15 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and 50 mm NaCl for 1 h at 25 °C. Complex formation was assessed by detecting the intensity fading of the inhibitor signal on a MALDI mass spectrum upon the addition of the enzyme immobilized on glioxal Sepharose® 4B as described for similar complexes (48). The complex was purified using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex-75 size exclusion chromatography column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in the same buffer and concentrated to 18.0 mg/ml (Centricon 10-kDa molecular weight cut-off concentration devices, Millipore). The protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm using a theoretical extinction coefficient (E280 nm1%) of 1.80 calculated for the complex with ProtParam (49) based on both protein sequences. Sample monodispersity and the hydrodynamic radius of the protein complex were evaluated by dynamic light scattering techniques as described previously (35, 38).

The screening of crystallization conditions was performed at 14 °C using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method in 96-well NeXtal plates (Qiagen). Protein solutions (300 nl) were mixed 1:1 (v/v) with commercially available reservoir solutions using a Honeybee 961 robot (Genomic Solutions). A monoclinic crystal (space group C2) of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex measuring up to 550 × 90 μm was detected when checking the plates after 1 year in condition 57 of the Qiagen Cryo Suite, which contained 0.425 m (NH4)2SO4, 0.85 m Li2SO4, 85 mm tri-sodium citrate, pH 5.6, and 15% glycerol.

Data Collection, Structure Determination, and Refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the consortium's beamline X13 at HASYLAB (DESY, Hamburg, Germany) equipped with a MARresearch CCD detector. A single crystal was mounted in a nylon loop and flash-cooled in a nitrogen gas stream at 100 K. Diffraction images were processed and scaled using MOSFLM and SCALA (50). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (51). The coordinates of free rShPI-1A (PDB code 3OFW (38)) and of free pancreatic elastase (PDB code 1QNJ (52)) were used as search models. Structure refinement was performed by alternate cycles of manual model rebuilding using COOT (53) and automated refinement (including isotropic B-factor refinement) applying Phenix software suite (54). As a test set for cross-validation, 5% of the reflections were randomly selected. In the final model, 207 water molecules as well as eight sulfate ions and seven glycerol molecules were added. Data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for rShPI-1/K13L·PPE

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell. Rp.i.m represents the precision-indicating merging R factor as defined below.

| Data collection | |

| Protein Data Bank code | 3UOU |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 132.65, 47.18, 42.68 |

| β (°) | 100.07 |

| Wavelength (Å) | |

| Resolutiona (Å) | 29.6-2.0 (2.10-2.00) |

| Rmergea (%) | 8.0 (25.7) |

| Rp.i.m.b (%) | 3.7 (13.4) |

| Rmeasc (%) | 7.7 (26.7) |

| No. of total reflections | 70,731 |

| No. of unique reflections | 17,481 |

| Mean I/σI | 13.6 (6.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.8 (99.9) |

| Multiplicity | 4.0 (3.6) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 29.6-2.0 (2.10-2.00) |

| No. of reflections | 17,120 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 16.6/21.1 |

| No of protein/water/other atoms | 2,242/206/82 |

| No. of reflections used in Rfree | 892 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |

| Main-chain/side-chain atoms | 25.4/28.4 |

| Ligand (glycerol)/ion (sulfate) | 48.4/41.5 |

| Water | 27.9 |

| Root mean square deviations | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.01 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.05 |

| Residues in Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored | 94.9 |

| Allowed | 5.1 |

a Rmerge = ΣhklΣi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl).

b Rp.i.m. = Σhkl{1/[N(hkl) − 1]}1/2 × Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl).

c Rmeas = Σhkl{N(hkl)/[N(hkl) − 1]}1/2 × Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl).

Structure Analysis

The stereochemical quality of the model was evaluated using VERIFY-3D (55), and MOLPROBITY (56). Interface calculations were performed using the PISA server (57). Analyses of atom-atom contacts and structural superposition were done using the WHAT IF program (58). The CryCo server was used for analysis of crystal contacts (59). PPE residues at the interface were numbered according to their similar topology with chymotrypsinogen (UniProt accession number P00766). Figs. 1, a and b, and 2–6 were generated with PyMOL (60).

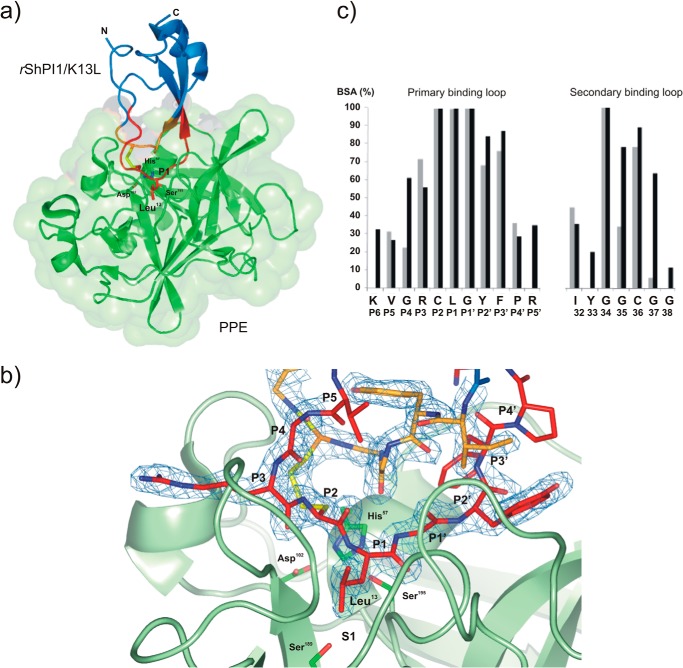

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex (PDB code 3UOU). a, schematic model of the overall structure of the complex between PPE (green, surface representation) and rShPI-1/K13L (blue), showing the changed P1 residue Leu13 of the inhibitor in stick representation. The primary (P6-P5′ sites) and secondary binding loops are highlighted in red and orange, respectively, and the linking disulfide bridge, Cys12–Cys36, is shown in yellow. b, close view of the entire complex interface centered on the S1 pocket of PPE, illustrating the formation of an antiparallel β-sheet by the inhibitor loops within the concave binding pocket of the enzyme that is typical for canonical inhibitors. The binding loops of rShPI-1/K13L (stick representation) are well defined by the 2Fo − Fc map (blue) countered at 1σ. The side chains of the catalytic triad residues His57, Asp102, and Ser195 as well as Ser189 at the bottom of the S1 pocket of PPE are highlighted in stick representation. c, buried surface area (BSA) of rShPI-1/K13L residues (black) involved in the PPE interface compared with that of wild-type rShPI-1A (gray) bound to trypsin. The buried surface area represents a percentage of the total surface area that is buried after complex formation. The amino acid sequence of rShPI-1/K13L and the corresponding Pn sites are shown.

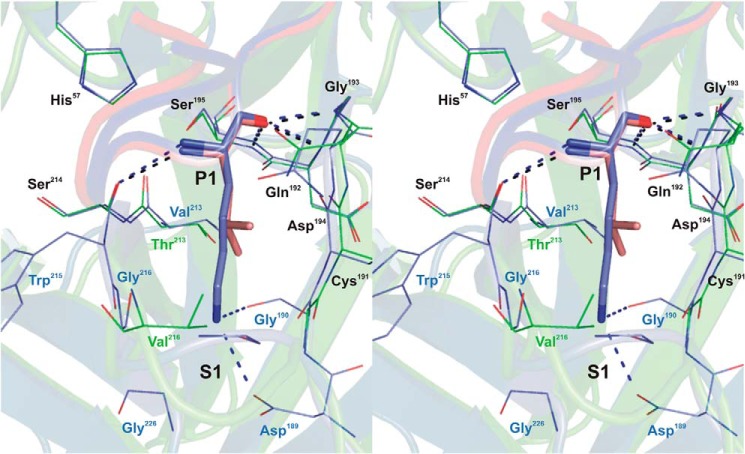

FIGURE 2.

Stereo view of the P1-S1 interaction at the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex interface compared with that in the trypsin complex of wild-type rShPI-1A (35). Enzyme residues involved in inhibitor contacts are shown as a line representation (PPE, green; trypsin, blue), and primary binding loop residues of rShPI-1/K13L (salmon) and wild-type rShPI-1A (blue) are displayed as sticks. Conserved residues are labeled in black, and non-conserved residues are in the same color as the corresponding enzyme. Hydrogen bonds are represented by black (PPE) and blue (trypsin) dashed lines. To simplify the figure, water molecules that are present in the trypsin complex (35) around the P1 position are not included. For details of the interactions in the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex, see Tables 3 and 4.

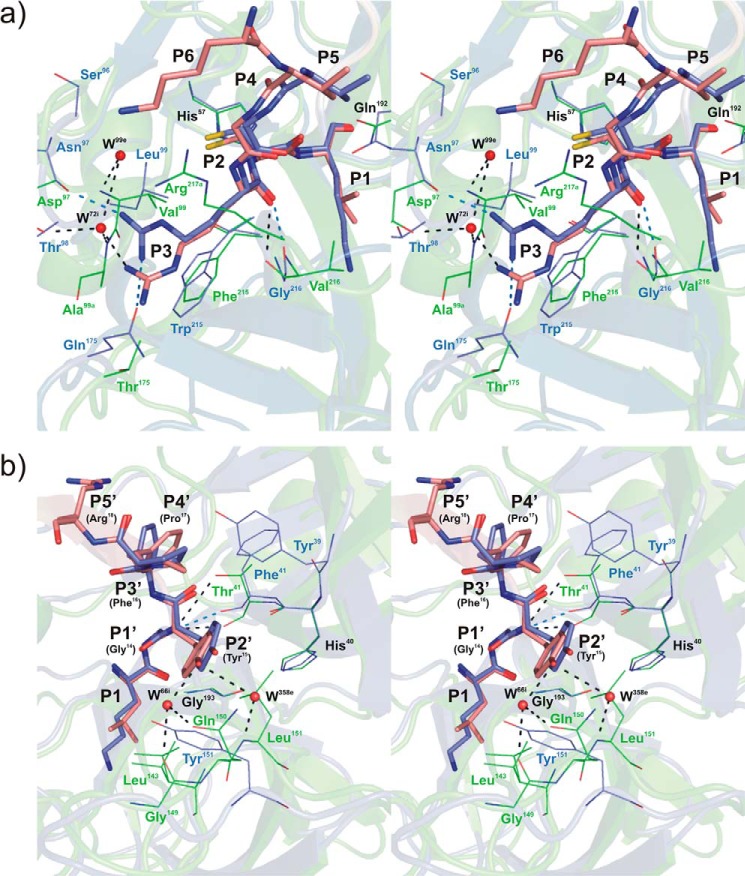

FIGURE 3.

Stereo view of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex interface superposed with that of wild-type rShPI-1A in complex with trypsin (35) at the Pn (a) and Pn′ (b) site of the primary inhibitor binding loop. Enzyme residues involved in inhibitor contacts are shown in line representation (PPE, green; trypsin, blue; conserved residues His57 and Gln192, black labels), and primary binding loop residues of rShPI-1/K13L (salmon) and wild-type rShPI-1A (blue) are displayed as sticks. The side chain at the P1 position of the inhibitor is included to enable a comparison with Figs. 1c and 2. Hydrogen bonds are represented by black (PPE) and blue (trypsin) dashed lines. Water molecules (W) are shown as red spheres and are labeled according to the PDB files in which they are assigned to the enzyme (e) or inhibitor (i) chains. Conformational differences between both complexes are restricted to position P3 at the Pn site of the primary binding loop. The P6 residue is only involved in the interface within the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex. For details of the interactions in the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex, see Tables 3 and 4.

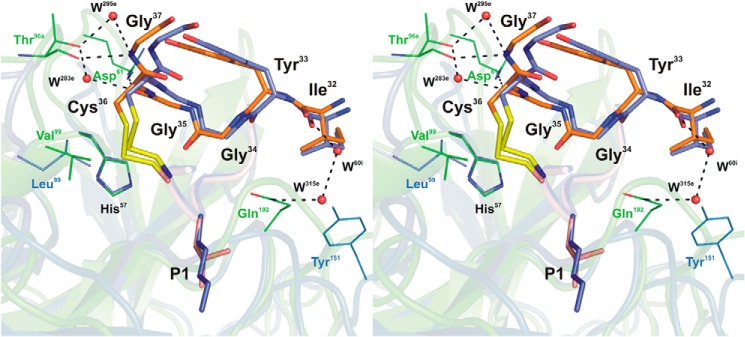

FIGURE 4.

Stereo view of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex interface maintained by the secondary binding loop superposed with that of wild-type rShPI-1A in complex with trypsin (35). Enzyme residues involved in inhibitor contacts are shown in line representation (PPE, green; trypsin, blue; conserved residue His57, black). Secondary binding loop residues (Ile32-Gly37) of rShPI-1/K13L(orange) and wild-type rShPI-1A (light blue) are displayed as sticks, and the P3-P3′ segment of the primary binding loop of both inhibitors is shown schematically (rShPI-1/K13L, salmon; rShPI-1A, dark blue) with sticks at the P1 side chain. Hydrogen bonds are represented by black dashed lines. Water molecules (W) are shown as red spheres and are labeled according to the PDB file in which they are assigned to the enzyme (e) chain. For details of the interactions, see Tables 3 and 4.

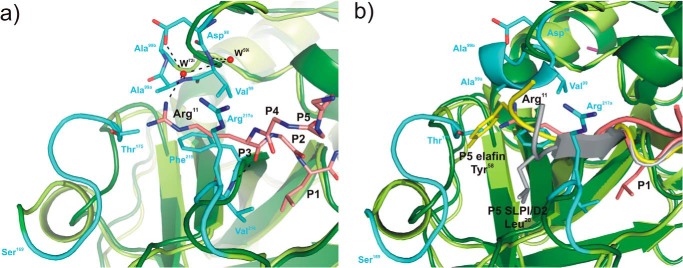

FIGURE 5.

Structural superposition of elastases in complex with BPTI-Kunitz- and WAP-type inhibitors focused on the non-prime subsite of the primary binding loops of the inhibitors. a, interface between PPE (dark green, schematic representation) and rShPI-1/K13L (salmon, stick representation) around the P3 residue (Arg11) at the Pn side of the primary binding loop (residues P6–P1). To highlight structural differences between elastases, the PPE structure is superposed with that of HNE (light green, PDB code 2Z7F), and PPE regions characterized by significant main chain deviations are highlighted in cyan. PPE residues interacting with the P3 residue of rShPI-1/K13L as well as the inhibitor side chains of Arg11 (P3) and Leu13 (P1) are shown in stick representation. Hydrogen bonds are represented with black dashed lines. Water molecules (W) are shown as red spheres and are labeled according to the PDB file in which they are assigned to the inhibitor (i) chain. b, corresponding interface region in the PPE (dark green) and HNE (light green) complexes of the WAP inhibitors elafin (gray, PDB code 1FLE) and SLPI/D2 (yellow, PDB code 2Z7F), respectively, shown in schematically. The side chains of residues at their P5 sites, Tyr58 in elafin and Leu20 in SLPI/D2 (12), are highlighted as sticks.

FIGURE 6.

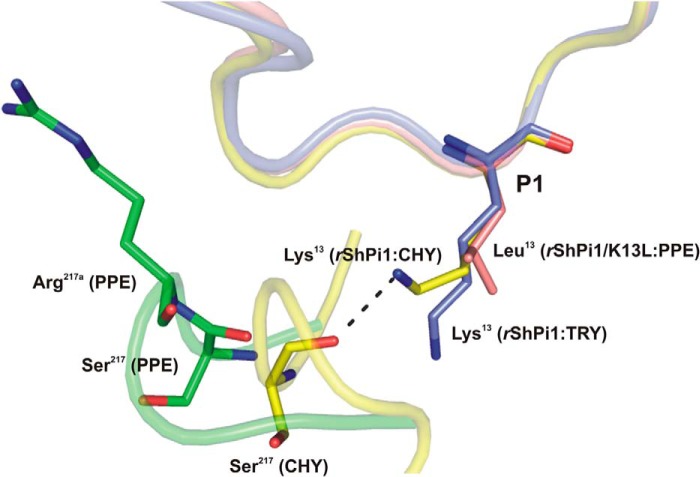

Superposition of the P1 side chain conformation of rShPI-1/K13L (salmon) in complex with PPE (green) compared with that of the wild-type inhibitor in complexes with trypsin (blue, PDB code 3MTQ) and chymotrypsin (yellow, PDB code 3T62). The inhibitor binding loops are shown schematically with the P1 residues in sticks. The insertion of Arg217A in PPE triggers structural differences that prevent a stabilizing interaction of the basic P1 residue with Ser217, as observed in the chymotrypsin complex (32). Here, the side chain of Lys13 adopts an up conformation, which is different from the down conformation in the trypsin complex (blue) and is stabilized by an H-bond with the oxygen atom of Ser217. However, the insertion of Arg217A in PPE (green) moves Ser217 away from P1, suggesting that a similar stabilizing bond with basic residues at P1 is not possible.

Results

Cloning, Production, and Purification of rShPI-1/K13L

The variant protein rShPI-1/K13L was produced in Pichia pastoris, yielding a level of 60 mg inhibitor/liter culture broth. A single cation exchange chromatography resulted in a pure inhibitor fraction, as confirmed by a single protein band on SDS-PAGE and a single peak in MALDI-TOF MS analysis. The molecular weight of 6096.47 Da (M+H+, 6097.47 Da) detected for the intact protein agrees with the expected value for the variant rShPI-1/K13L (6096.82 Da). In contrast to previous results with BPTI (61, 62), the correct processing of the α-factor-ShPI-1 fusion without the N-terminal motif Glu-Ala-Glu-Ala was obtained here. Peptide mass mapping after tryptic digestion verified the entire protein sequence including the K13L exchange. The experimental masses of three peptides (Cys12-Arg18, 912.46 Da; Lys8-Arg18, 1352.75 Da; and Val9-Lys27, 2243.23 Da) agreed with the calculated values, considering the presence of Leu at the mutated P1 position of the inhibitor.

Inhibitory Activity of rShPI-1/K13L

Incubation of trypsin, chymotrypsin, and HNE with rShPI-1/K13L resulted in an inhibition of these serine proteases consistently characterized by Ki values within the nanomolar range (Table 2) as described previously for the natural and recombinant wild type-like inhibitors (21, 37). Solely the binding affinity to trypsin is significantly decreased (∼100-fold) as a result of the mutation, whereas rShPI-1/K13L appears to be slightly more potent against chymotrypsin and HNE than the wild-type inhibitor. In agreement with previous mutagenesis studies of BPTI (25–28), the replacement of the large basic Lys residue against the smaller hydrophobic leucine residue transformed rShPI-1/K13L into a high-affinity PPE inhibitor. This additional activity has never been observed for natural or wild-type rShPI-1A, even if an Io/Eo molar ratio of 170 is used (21, 37). The PPE inhibition activity was stable after incubation for 15 s, indicating that the enzyme, the inhibitor, and the substrate as well as their complexes were in equilibrium. The observed substrate dependence of the PPE inhibition (residual enzyme activity increased with substrate concentration) is characteristic for a competitive mechanism. Moreover, the concave inhibition curves recorded under the experimental conditions of [Eo]/Ki = 1–10 (data not shown) showed that rShPI-1/K13L is a reversible and tight-binding inhibitor of all four enzymes.

TABLE 2.

Real inhibition constants (Ki) of rShPI-1A wild type and K13L variant for serine proteases

Ki values are reported in nm. NI, no inhibition was detected even at Io/Eo molar ratio of 170 incubated for 30 min. Real Ki values were calculated according to the equation Ki = Ki app/([S0]/(Km) + 1) considering the substrate concentration [So] and the Km values. The following substrates were used for: trypsin, Bz-Arg-pNA (41); HNE, MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA (42); chymotrypsin, Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA (40); and PPE, Suc-Ala-Ala-Ala-pNA (42).

| Enzyme | rShPI-1A wt | rShPI-1/K13L |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 320 ± 35 |

| Chymotrypsin | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| Human neutrophilic elastase | 23.5 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| Porcine pancreatic elastase | NI | 12.0 ± 2.6 |

Crystallization and Structure Determination of rShPI-1/K13L in Complex with PPE

Prior to crystallization trials, specific complex formation between rShPI-1/K13L and PPE was confirmed by intensity-fading MALDI-TOF MS, dynamic light-scattering measurements, and size exclusion chromatography (data not shown). The purified rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex formed monoclinic crystals belonging to the space group C2 and diffracted up to a resolution of 2.0 Å. The asymmetric unit contained one complex molecule. After structure determination by molecular replacement using the coordinates of free PPE (PDB code 1QNJ) and free wild-type rShPI-1A (PDB code 3OFW) as search models, the entire PPE polypeptide as well as all inhibitor residues at the complex interface could be traced completely in the electron density map. Only the β-hairpin segment Phe21-Lys27 of the inhibitor and its C-terminal residue Ala55 are poorly defined because of increased flexibility. All residues are located within the most favored or allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, reflecting the quality of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE structure. The details of data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Overall Structure

The overall fold of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex closely resembles that expected for an interaction of a serine protease and a canonical inhibitor (Fig. 1a) (32–35). The complex interface buries an inhibitor surface area of 865.7 Å2 (23.7% of its total solvent-accessible surface), which is slightly increased compared with rShPI-1A complexes with trypsin (765.1 Å2 and 18.2%) and chymotrypsin (787.4 Å2 and 21.2%). This is due to an extended interface involving residues Lys8 (P6) to Arg18 (P5′) located at the primary binding loop of rShPI-1/K13L, as well as a secondary interaction site comprising the inhibitor residues Ile32 to Gly38. Both interaction loops are stabilized by the disulfide bond Cys12–Cys36, keeping the primary loop in a well ordered conformation, which enables the formation of an antiparallel β-sheet within the concave binding pocket of PPE (Fig. 1b) that is typical for canonical inhibitors. An enzyme surface area of 706.5 Å2 (6.7%) is buried in the complex, which is slightly lower than that in the PPE complexes with the canonical inhibitors HEI-TOE (7.3%), elafin (7.6%), and C/E-1 (8.6%).

Neither the K13L variant nor the PPE interaction significantly affected the overall inhibitor fold, as indicated by a root mean square deviation of 0.532 Å over 54 superposed Cα atoms of unbound wild-type rShPI-1A (PDB code 3OFW) and PPE-bound rShPI-1/K13L. Deviations of up to 1.2 Å observed at Arg11 (P3), Tyr15 (P2′), and His47 to Gln48 are most likely attributable to the high B-factors and crystal contacts identified previously at these positions in the crystal structure of free rShPI-1A (PDB code 3OFW). Additional deviations have been detected for Ser23 to Thr25, but these β-hairpin residues are largely undefined within the electron density map as mentioned previously. Likewise, native and inhibitor-bound PPE (PDB code 3EST) showed no significant structural differences (root mean square deviation of 0.568 Å over 240 superposed Cα atoms). The positions of the catalytic residues His57, Asp102 and Ser195, as well as Ser189 and Gly193 within the S1 pocket, remained highly conserved in both enzyme molecules. In contrast, enzyme residues at other prime and non-prime subsites were slightly affected by inhibitor binding. Significant deviations of up to 2.3 Å (Cα positions) were detected in the loop region Arg145–Gln150 close to the S2′ site (Leu143/Leu151), at Ser36C/Ser37 and Asp60/Arg61 near the Sn′ sites, as well as at the calcium-binding loop of the elastase (Asn74–Gly78). However, according to CryCo server analysis, most of these displacements may also be attributed to the differences detected in the crystal packing environments.

rShPI-1/K13L·PPE Interface and Comparison with the rShPI-1A·trypsin Complex

In common with other canonical inhibitors, the primary direct interactions of rShPI-1/K13L with PPE are provided by residues at positions P2, P1, and P1′ of the primary binding loop, which are completely buried due to complex formation (Fig. 1c). Compared with the interface of trypsin-bound rShPI-1A (PDB code 3M7Q) (35), residues Gly10 (P4), Tyr15 (P2′), and Pro16 (P3′) provide an increased contribution to the elastase interaction, whereas the impact of Arg11 (P3) and Pro17 (P4′) is slightly reduced. The rShPI-1/K13L·PPE interface is extended by one residue at both sites of the scissile bond compared with known complexes of BPTI and rShPI-1A with trypsin (32–35). The accessible surface area of the outer residues, Lys8 (P6) and Arg18 (P5′), is buried by more than 30% after complex formation with PPE (Fig. 1c), whereas these residues do not show any contribution to the rShPI-1A·trypsin complex (35). An overall number of 156 direct enzyme-inhibitor contacts is shorter than 4 Å, including 144 hydrophobic contacts and 10 hydrogen bonds; these are involved in the stabilization of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE interface (Table 3). This is a slight increase compared with the trypsin complex (116 hydrophobic contacts and 10 H-bonds) (35). Direct H-bonds are provided by Arg11 (P3), Leu13 (P1), Gly14 (P1′), and Tyr15 (P2′) at the canonical loop segment, as well as by Gly35 and Gly37 at the secondary binding loop. Further interface stabilization is provided by polar interactions mediated by 10 water molecules connecting the P4, P3, and P2′ sites as well as Ile32, Gly35, and Gly37 of rShPI/1/K13L with corresponding subsites in PPE (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Enzyme-inhibitor interactions in the PPE complex of rShPI-1/K13L

PPE residues are numbered according to their similar topology with chymotrypsinogen. The total number of contacts between a pair of residues (≤4.0 Å) is shown in parentheses, then the closest atoms are listed, and distances (Å) are given in square brackets. Hydrogen bonds, displayed in a bold underlined font, were scored using the PDBe PISA server (57), applying the following parameters: maximal donor-acceptor distance, 3.50 Å; maximal hydrogen-acceptor distance, 2.50 Å; maximal angular errors, 90.00. Enzyme residues Arg217A and Ala99A represent native insertions in the sequence of PPE as compared with chymotrypsin.

| rShPI-1/K13L residue | PPE residue | (Total contacts) Closest atoms [distance] |

|---|---|---|

| [Å] | ||

| P6 Lys8 | Arg217A | (6) CE--NH2 [3.59] |

| P5 Val9 | Gln192 | (1) CG1--NE2 [3.83] |

| P4 Gly10 | Arg217A | (2) C--CG [3.82] |

| P3 Arg11 | Ala99A | (1) NH1--CB [3.87] |

| Thr175 | (1) NH2--OG1 [3.90] | |

| Phe215 | (5) O--CB [3.10] | |

| Val216 | (10) O--N [2.82] | |

| Arg217A | (3) CG--CG [3.47] | |

| P2 Cys12 | His57 | (8) CB--NE2 [3.52] |

| Val99 | (2) SG--CG2 [3.76] | |

| Gln192 | (4) O--OE1 [2.97] | |

| Ser214 | (3) CA--O [3.51] | |

| P1 Leu13 | His57 | (1) N--NE2 [3.86] |

| Gly190 | (3) CD1--C [3.47] | |

| Cys191 | (6) CD2--C [3.56] | |

| Gln192 | (9) CA--OE1 [3.37] | |

| Gly193 | (4) O--N [2.73] | |

| Asp194 | (1) O--N [3.26] | |

| Ser195 | (11) C-OG [2.76]; O--N [3.04] | |

| Thr213 | (1) CD1--CG2 [3.78] | |

| Ser214 | (1) N--O [3.33] | |

| Val216 | (4) CD2--CG2 [3.52] | |

| P1′ Gly14 | Thr41 | (2) C--O [3.86] |

| His57 | (1) N--NE2 [3.75] | |

| Gln192 | (5) O--OE1 [3.02] | |

| Gly193 | (2) C--N [3.58] | |

| Ser195 | (4) N--OG [3.02] | |

| P2′ Tyr15 | His40 | (1) CD2--O [3.87] |

| Thr41 | (8) N--O [3.00] | |

| N--OG1 [3.80] | ||

| Leu143 | (2) CE1--CD1 [3.71] | |

| Leu151 | (11) CD1--CD2 [3.47] | |

| Gly193 | (3) CB--CA [3.69] | |

| P3′ Phe16 | Thr41 | (5) CZ--OG1 [3.62] |

| Cys58 | (1) CZ--O [3.63] | |

| Arg61 | (4) CZ--NE [3.54] | |

| P4′ Pro17 | Tyr35 | (2) CE1--OE1 [3.26] |

| P5′ Arg18 | Arg61 | (1) NH2--NH1 [3.22] |

| 32 Ile32 | Gln192 | (1) CG2--CB [4.00] |

| 34 Gly34 | His57 | (2) O--CD2 [3.64] |

| Gln192 | (1) CA--OE1 [3.70] | |

| 35 Gly35 | His57 | (2) O--O [3.56] |

| Arg61 | (3) O--NH2 [2.77] | |

| 36 Cys36 | Thr96 | (4) CB--O [3.58] |

| Val99 | (2) SG--CB [3.84] | |

| 37 Gly37 | Thr96 | (2) N--O [2.91] |

TABLE 4.

Water-mediated hydrogen bonds at the interface of the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex

PPE residues are numbered according to their similar topology with chymotrypsinogen. Numbers in parentheses refer to donor-acceptor distances (Å). Water molecules (W) are labeled according to the numbers in the PDB file, in which they are assigned to the enzyme (e) or inhibitor (i) chains. The suffix “A” indicates amino acid insertions in the PPE sequence compared to that of chymotrypsinogen. The following parameters were used to identify an H-bond: maximal donor-acceptor distance, 3.50 Å; maximal hydrogen-acceptor distance, 2.50 Å; maximal angular errors, 90.00.

| Position | K13L·PPE |

|---|---|

| Å | |

| P4 | Gly10i O--W65i (3.05) |

| W65i--Arg217Ae (3.22) | |

| Gly10i O--W304e (2.84) | |

| W304e--Gln192e OE1 (2.84) | |

| P3 | Arg11i NH1--W72i (2.86) |

| W72i--Asp97e OD1 (3.03) | |

| W72i--Ala99AeN (3.06) | |

| W72i--W59i (3.68)--Val99eN (3.05) | |

| P2′ | Tyr15i OH--W66i (2.69) |

| W66i--Gln150e OE1 (2.99) | |

| W66i--Gly149eO (2.77) | |

| Tyr15i OH--W358e (3.28) | |

| W358e--Leu151eN (2.89) | |

| 2nd loop | Ile32i O--W60i (2.88)--W315e (3.67) |

| W315e--Gln192e NH1 (2.87) | |

| Gly35i O--W293e (2.74) | |

| W293e--Thr96e OG1 (2.60) | |

| Gly37i N--W295e (3.43) | |

| W295e--Thr96e OG1 (2.61) |

At the modified P1 position of rShPI-1/K13L, Leu13 accounts for 27% of the direct interactions with PPE. All backbone atoms share equivalent positions compared with the rShPI-1A·trypsin complex (35) (Fig. 2). In agreement with the general serine protease catalysis and substrate-like inhibition mechanisms, the carbonyl oxygen atom of Leu13 occupies the oxyanion hole, establishing three hydrogen bonds to the backbone nitrogen atoms of PPE residues Gly193, Asp194, and Ser195, together with an H-bond to Ser214 via its nitrogen atom. The hydrophobic side chain of Leu13 sticks into the hydrophobic S1 pocket of PPE formed by the enzyme residues Gly190, Thr213, and Val216, as well as the hydrophobic parts of the Gln192 and Cys191 side chains, establishing important van der Waals contacts that stabilize the interaction. As expected, Leu13 at P1 is not involved in water-mediated interactions, in contrast to Lys13 in the trypsin complex of the wild-type inhibitor (35). Moreover, the shorter side chain of Leu13 at the mutated P1 site cannot interact with PPE residues 189, 190, 215, and 216, as observed in the trypsin complex of the wild-type inhibitor (Fig. 2).

The canonical segment of the primary inhibitor binding loop (positions P3–P3′) of rShPI-1/K13L adopts a well conserved conformation that is comparable within the PPE and the trypsin complexes of ShPI-1. Direct superposition reveals only slight rearrangements of side-chain atoms at the P3 site (Arg11) because of its specific adaptation to the S3 pocket of PPE (Fig. 3a). As a consequence, two additional H-bonds detected previously in the rShPI-1A·trypsin complex (35) are absent, and only the typical H-bond with the nitrogen atom of residue 216 remains conserved. Additional differences at the non-prime side are detected at position P4, where Gly10 interacts with the inserted Arg217A of PPE that is absent in trypsin (35). At the prime subside of the primary binding loop, residue Tyr15 (P2′) of rShPI-1/K13L is involved in several direct and water-mediated H-bonds with PPE (Fig. 3b), whereas only one H-bond stabilizes the trypsin complex at the P2′ position (35). In contrast, the hydrophobic contacts established between Pro17 (P4′) and the enzyme residue Tyr39 in the ShPI-1·trypsin complex are reduced here (Table 3), as the bulky hydrophobic site chain of Tyr39 is replaced by Ala in PPE. Moreover, additional van der Waals contacts of the hydrophobic part of the Lys8 side chain (P6) with the carbon moiety of Arg217A in PPE as well as side-chain interactions between Arg18 (P5′) and Arg61 in PPE (3.2 Å) extend the interface compared with the trypsin complex, as mentioned previously.

Residues located at the secondary binding loop of rShPI-1/K13L (Ile32 to Gly38) are significantly more involved in the interaction with PPE than with trypsin. The buried surface area of all corresponding rShPI-1/K13L residues is obviously increased compared with equivalent residues within the trypsin complex (Fig. 1c). Gly35 and Gly37 establish direct H-bonds with Arg61 and Thr96 of PPE, in addition to water-mediated interactions (Fig. 4). The entire secondary loop accounts for hydrophobic contacts with PPE residues His57, Arg61, Thr96, Val99, and Gln192 (Table 3). In contrast, no H-bonds and significantly less van der Waals contacts are provided by the secondary binding loop upon trypsin binding (35). Glu44, located C-terminally outside of this loop in rShPI-1/K13L, is also slightly buried after complex formation, establishing an interaction with Arg61 of PPE (OE2-NH1) characterized by a longer than usual distance for a salt bridge (∼5.0 Å). All of these interactions are favored in PPE because of the increased length of the loop structures containing residues 61–64 and 97–99 as compared with trypsin (Fig. 4).

Comparison with Elastase Complexes of Other Canonical Inhibitors

As expected, all of the main contacts to PPE established by the P1 site of rShPI-1A/K13L are highly conserved compared with the canonical inhibitors elafin (P1, Ala), C/E-1 (P1, Leu), and HEI-TOE (P1, Leu) belonging to the WAP, Ascaris, and Kazal/squash families, respectively (14–16). Main differences are thus restricted to the prime/non-prime subsites of the interface. An unusually large buried surface area is reported for PPE in complex with the Ascaris inhibitor C/E-1 (8.6%), mainly because of the deep penetration of Ser217 into an inhibitor surface pocket formed by positions P15 to P13 and P10′ to P13′ (15). This has not been detected in other elastase/canonical inhibitor complexes. Similar to the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE complex presented here, a shorter primary interaction segment comprising the P5 to P2′ sites together with a three-residue secondary binding loop is reported for elafin (14). The hybrid squash inhibitor binds via well defined interactions at positions P4 to P4′, supported by five additional weak contacts to the elastase (16). Concordantly, the inhibition strength of C/E-1 is the highest (Ki = 0.063 nmol/liter (63), whereas similar Ki values have been reported for the inhibitors elafin (6.0 nmol/liter (14) or 1.0 nmol/liter (64)) and HEI-TOE (0.98 nmol/liter (16)), almost comparable with rShPI-1/K13L (12 nmol/liter) reported in this study.

To obtain first insights into the structural determinants for an interaction with HNE, we compared the rShPI-1/K13L·PPE interface with that of the chelonians elafin (P1, Ala24) and 1/2SLPI (P1, Leu72) in complex with PPE and HNE, respectively. Chelonians represent the only family of canonical inhibitors with three-dimensional structures determined for complexes with both elastases (12, 14). As expected for canonical inhibitors from different families, the backbone conformation of the canonical P3-P3′ segment is similar among these inhibitors, but differences have been detected for flanking residues (19, 65). Most noteworthy, the side chain of Arg11 at the P3 site of the Kunitz-type inhibitor rShPI-1/K13L extends into a similar enzyme region as the residues at the P5 position of the chelonians elafin and 1/2SLPI (Fig. 5). Thus, Arg11 of rShPI-1/K13L interacts with residue Thr175 within the PPE surface loop segment Ser169–Val176, which is defined as the S5 pocket in the elafin-PPE complex (12, 14). In addition, the P3 site of rShPI-1/K13L (Arg11) interacts with Ala99A, Phe215, Val216, and Arg217A of PPE (Table 3) and is indirectly H-bonded to Asp97, Val99, and Ala99A. These residues represent insertions into the sequence of PPE that cause remarkable structural differences in the loops in which they are located, as compared with similar regions of HNE (Fig. 5). Accordingly, the P3 site of ShPI-1 may contribute to differences in selectivity toward HNE and PPE.

Discussion

The interaction between BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitors and serine proteases from the chymotrypsin family has been well studied. However, the known three-dimensional structures of enzyme complexes with inhibitors of this family are limited to trypsin- and chymotrypsin-like enzymes (32–35). The inhibitor specificity is usually categorized in terms of the P1-S1 interaction, mainly considering the enzyme residues at positions 189, 216, and 226 of the S1 pockets. In chymotrypsin, the combination of Ser189, Gly216, and Gly226 creates a deep hydrophobic pocket that correlates with the usual hydrophobicity of the P1 residue in a chymotrypsin substrate or inhibitor. In contrast, trypsin-like enzymes contain a negatively charged S1 site due to the presence of Asp189 at the bottom, which accounts for their specificity against substrates containing Arg or Lys residues at P1 position.

The S1 pocket of elastase-like enzymes is significantly narrowed overall by more bulky side chains at positions 216 and 226, usually resulting in the recognition of small or medium-sized aliphatic P1 residues (11). At the bottom of the S1 pocket, the respective residue (Ser189 in PPE or Gly189 in HNE) is inaccessible to the P1 side chain of the inhibitor, as it is covered by the hydrophobic parts of Ile138 and Thr226 (in PPE) or Val190 (in HNE). Compared with PPE, the S1 pocket of HNE shows an increased flexibility, enabling the adaptation to a broader variety of P1 side chains (11, 23). The largest backbone atom divergence between PPE and HNE at this side occurs at positions 192 (Gln192 in PPE and Phe192 of HNE) and 226 (Thr226 in PPE and Asp226 in HNE). Moreover, HNE harbors a negative charge from Asp226 (that replaces Thr226 of PPE) within its S1 pocket, which is largely shielded by Val216 and Val190. However, modeling studies with the Kazal-type inhibitor CmPI-2 suggest that penetration of a basic P1 side chain is still possible (24). A salt link with Asp226 is established, supported by additional contacts with Ser214 and Ala227 of HNE, which were not detected for a homologous inhibitor that harbors Leu at P1 position. These unique characteristics of HNE could explain the selective elastase inhibitory activity determined for wild-type rShPI-1A and for BPTI (18), both of which contain Lys at position P1.

In PPE, the completely non-polar as well as rigid and narrow S1 site in turn prevents the efficient accommodation of the Lys side chain, as reported for the BPTI (32) and rShPI-1A complexes of chymotrypsin (PDB code 3T62)3 that comparably feature a deep hydrophobic S1 pocket. However, tight inhibitor binding to chymotrypsin is maintained by an alternative “up” conformation of the P1 Lys side chain instead of extending directly into the pocket (“down” conformation). This shift establishes a new set of H-bonds that compensate the interface stabilization, involving the NZ atom of Lys (inhibitor) and the main-chain oxygen atom of Ser217 at the entry of the chymotrypsin S1 site (32). The first crystal structure of a BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitor in complex with an elastase-like enzyme reported in this study strongly indicates that a similar stabilization of the up conformation at the PPE S1 site is not possible. Although Ser217 remains conserved within the PPE sequence, the insertion of Arg217A promotes an altered conformation of the corresponding loop in PPE compared with other serine proteases, shifting Ser217 around 4.7 Å away from the P1 side chain and thus preventing stabilizing interactions (Fig. 6). This is reflected by weak (BPTI (18)) or undetectable (ShPI-1 (21)) binding of the wild-type inhibitors to PPE.

As observed previously for BPTI and in agreement with the preference for aliphatic residues at P1, a tight-binding inhibitor of both elastases, HNE and PPE, was obtained in this study by substitution of the P1 Lys residue of the BPTI-Kunitz-type domain ShPI-1 against Leu. The aliphatic side chain improves the hydrophobic interaction with the narrow S1 pocket, which is formed by Gly190, Thr213, and Val216 in PPE. However, the overall conformation and interaction mode of the rShPI-1/K13L primary binding loop is not affected following the canonical mechanism usually reported for similar complexes with trypsin- and chymotrypsin-like enzymes (32–35). Most of the interactions are established by Leu15 at the P1 site, including the H-bonds typical for a substrate-like inhibition mechanism, and other contacts with aliphatic enzyme residues (Thr213 and Val216) that define the specificity for PPE. As expected, the hydrophobicity increase at the P1 side chain is accompanied by a moderate optimization of chymotrypsin inhibition by rShPI-1/K13L. Because the S1 pocket of chymotrypsin is characterized by the highest hydrophobic nature of these serine proteases, the associated Ki value decreased to the values reported for an equivalent K15L exchange of BPTI against this enzyme (7.7 × 10−10 m (27)).

Despite the absence of a positively charged residue at P1, the rShPI-1/K13L variant is still active against trypsin. Only a 2-orders of magnitude increase in the associated Ki value was detected compared with that of the wild-type inhibitor. A more significant effect was provoked by the equivalent exchange in BPTI, with Ki values shifting by 7 orders of magnitude from 6 × 10−14 m for the wild-type molecule to 1.8 × 10−7 m for the K15L variant (27). Because the P1 interactions of BPTI and rShPI-1A in the S1 pocket of trypsin are highly similar (35), significant differences in the contribution of further interaction sites to the overall complex stability were strongly indicated. The impact of subsites other than P1 directly correlates with the fitting accuracy of the latter within its S1 enzyme binding pocket. The weaker the interaction of the P1 residue, the more prominent is the contribution of other inhibitor residues to the enzyme binding (32). In this context, we recently reported on an important stabilizing role of Arg11 at the P3 position in the ShPI-1-trypsin interface that is thus far unique within this inhibitor family (35). This remote contribution is suggested to compensate for the reduced P1 interactions of the rShPI-1/K13L variant more effectively than in the corresponding BPTI complex.

The rShPI-1/K13L·PPE structure reported here provides the first structure-based evidence for a comparable impact of Arg11 (P3) in the interface stabilization of a BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitor and an elastase. Consequently, previous mutagenesis studies that proposed a correlation of the P3 residue in BPTI with its inhibitory activity against elastases without any structural knowledge are confirmed (26, 30). Residues different than the native Pro13 at P3 position in BPTI have been suggested to induce a more favorable primary loop conformation to strengthen HNE binding without affecting the PPE interaction 26). Our structure shows that the side chain of Arg11 mediates interactions with a region of PPE that is characterized by sequential and structural differences compared with HNE, particularly involving loop structures containing Val99A, Thr175, and Arg217A (according to PPE topology). This result supports a potential role of the P3 interaction in the elastase selectivity of BPTI-Kunitz inhibitors. In this regard, mutagenesis studies involving the squash seed Cucurbita maxima trypsin inhibitor III (CMTI-III) have shown that inhibition of HNE, but not of PPE or other serine proteases, occurs even if a Gly residue is located at P1 position, likewise indicating an impact of interactions distant to the S1 site in interface stability and elastase selectivity (6).

Moreover, we have identified a more significant impact of the secondary binding loop in the interaction with PPE compared with previous reports of corresponding trypsin and chymotrypsin complexes (32–35), again supporting previous mutagenesis studies now on a structural level. Three basic residues in the segment 39RAKR42 of the BPTI secondary loop (equivalent to 37GGNG40 in ShPI-1) have been reported to affect the inhibition activity against HNE. Substitution of this sequence in a BPTI/K15V variant by the equivalent stretch from Bikunin domain 2 (39MGNG42) increases the inhibition of HNE, whereas its effect on PPE inhibition has not been investigated (30). The increased amount of Gly residues within this region closely mimics the corresponding secondary loop sequence of ShPI-1, which is strongly involved in PPE interface stabilization via H-bonds according to the structural evidence provided here.

In this study we obtained a high-affinity PPE inhibitor from the BPTI-Kunitz family by site-directed mutagenesis at the P1 position. The detailed investigation of the enzyme-inhibitor interactions confirmed the expected canonical mechanism with a more important role of the inhibitor secondary binding loop compared with other S1 family serine proteases with known structures. Our data show that the P3 residue of rShPI-1/K13L points into a PPE region with significant structural difference compared with HNE, which has been described to be involved in the selectivity of WAP inhibitors toward HNE or PPE. Consequently, residues at the secondary binding loop and at the P3 site of ShPI-1 represent interesting targets for site-specific mutagenesis to improve binding affinity and/or direct selectivity against elastase-like enzymes. Because ShPI-1 does not contain any residue that can be oxidized within the serine protease binding loops, it represents a suitable scaffold to be developed into a specific inhibitor that binds HNE with high affinity, which is urgently required.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Mansur for providing the pMB301 vector and Dr. F. P. Chávez (University of Chile) for support during the first mutagenesis experiments, as well as Drs. G. Cobaleda and S. Bromsoms (Autonomous University of Barcelona) for support in intensity-fading MALDI-TOF and peptide mapping experiments. We also thank Dr. T. Pons (Spanish Center for Cancer Research) for helpful advice concerning structural superposition and analysis and Katrin Seelhorst for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grants F4086-1 and F4086-2 from the International Foundation for Science, Sweden; the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD); the excellence cluster (The Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging-Structure, Dynamics, and Control of Matter at the Atomic Scale) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; and Grant 01DN13028 from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3UOU) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

R. García-Fernández, R. Domínguez, D. Oberthuer, T. Pons, Y. González-González, M. A. Chávez, C. Betzel, and L. Redecke, unpublished observation.

- HNE

- human neutrophil elastase

- BPTI

- bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor

- PDB

- protein data bank

- pNA

- p-nitroanilide

- PPE

- porcine pancreatic elastase

- ShPI-1

- Stichodactyla helianthus protease inhibitor 1

- WAP

- wheat acidic protein.

References

- 1. Debelle L., Tamburro A. M. (1999) Elastin: molecular description and function. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31, 261–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Büchler M., Uhl W., Malfertheiner P. (1987) Elastase 1 in Acute Pancreatitis: Research and Clinical Management (Beger H. G., Büchler M. D., eds), pp. 110–117, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ooyama T., Sakamato H. (1995) Elastase in the prevention of arterial aging and the treatment of atherosclerosis. Ciba Found. Symp. 192, 307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapiro S. D. (1995) The pathogenesis of emphysema: the elastase:antielastase hypothesis 30 years later. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 107, 346–352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Korkmaz B., Horwitz M. S., Jenne D. E., Gauthier F. (2010) Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 726–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McWherter C. A., Walkenhorst W. F., Campbell E. J., Glover G. I. (1989) Novel inhibitors of human-leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G: sequence variants of squash seed protease inhibitor with altered protease selectivity. Biochemistry 28, 5708–5714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chughtai B., O'Riordan T. G. (2004) Potential role of inhibitors of neutrophil elastase in treating diseases of the airway. J. Aerosol Med. 17, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moroy G., Alix A. J., Sapi J., Hornebeck W., Bourguet E. (2012) Neutrophil elastase as a target in lung cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 12, 565–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun Z., Yang P. (2004) Role of imbalance between neutrophil elastase and alpha 1-antitrypsin in cancer development and progression. Lancet Oncol. 5, 182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lane A. A., Ley T. J. (2003) Neutrophil elastase cleaves PML-RARα and is important for the development of acute promyelocytic leukemia in mice. Cell 115, 305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bode W., Meyer E., Jr., Powers J. C. (1989) Human leukocyte and porcine pancreatic elastase X-ray crystal structures, mechanism, substrate specificity, and mechanism-based inhibitors. Biochemistry 28, 1951–1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koizumi M., Fujino A., Fukushima K., Kamimura T., Takimoto-Kamimura M. (2008) Complex of human neutrophil elastase with 1/2SLPI. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 15, 308–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bode W., Wei A. Z., Huber R., Meyer E., Travis J., Neumann S. (1986) X-ray crystal structure of the complex of human leukocyte elastase (PMN elastase) and the third domain of the turkey ocomucoid inhibitor. EMBO J. 5, 2453–2458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsunemi M., Matsuura Y., Sakakibara S., Katsube Y. (1996) Crystal structure of an elastase-specific inhibitor elafin complexed with porcine pancreatic elastase determined at 1.9 A resolution. Biochemistry 35, 11570–11576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang K., Strynadka N. C., Bernard V. D., Peanasky R. J., James M. N. (1994) The molecular structure of the complex of Ascaris chymotrypsin/elastase inhibitor with porcine elastase. Structure 2, 679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aÿ J., Hilpert K., Krauss N., Schneider-Mergener J., Höhne W. (2003) Structure of a hybrid squash inhibitor in complex with porcine pancreatic elastase at 1.8Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kunitz M., Northrop J. H. (1936) Isolation from beef pancreas of crystalline trypsinogen, trypsin, a trypsin inhibitor, and an inhibitor-trypsin compound. J. Gen. Physiol. 19, 991–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ascenzi P., Bocedi A., Bolognesi M., Spallarossa A., Coletta M., De Cristofaro R., Menegatti E. (2003) The bovine basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (Kunitz inhibitor), a milestone protein. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 4, 231–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krowarsch D., Cierpicki T., Jelen F., Otlewski J. (2003) Canonical protein inhibitors of serine proteases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60, 2427–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schechter I., Berger A. (1967) On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delfín J., Martínez I., Antuch W., Morera V., González Y., Rodríguez R., Márquez M., Saroyán A., Larionova N., Díaz J., Padrón G., Chávez M. (1996) Purification, characterization and immobilization of proteinase inhibitors from Stichodactyla helianthus. Toxicon 34, 1367–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sinha S., Watorek W., Karr S., Giles J., Bode W., Travis J. (1987) Primary structure of human neutrophil elastase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 2228–2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McBride J. D., Freeman H. N., Leatherbarrow R. J. (1999) Selection of human elastase inhibitors from a conformationally constrained combinatorial peptide library. Eur. J. Biochem. 266, 403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. González Y., Pons T., Gil J., Besada V., Alonso-del-Rivero M., Tanaka A. S., Araujo M. S., Chávez M. A. (2007) Characterization and comparative 3D modeling of CmPI-II, a novel 'nonclassical' Kazal-type inhibitor from the marine snail Cenchritis muricatus (Mollusca). Biol. Chem. 388, 1183–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tschesche H., Beckmann J., Mehlich A., Schnabel E., Truscheit E., Wenzel H. R. (1987) Semisynthetic engineering of proteinase inhibitor homologues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 913, 97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kraunsoe J. A., Claridge T. D., Lowe G. (1996) Inhibition of human leukocyte and porcine pancreatic elastase by homologues of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Biochemistry 35, 9090–9096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krowarsch D., Dadlez M., Buczek O., Krokoszynska I., Smalas A. O., Otlewski J. (1999) Interscaffolding additivity: binding of P1 variants of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor to four serine proteases. J. Mol. Biol. 289, 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kiczak L., Kasztura M., Koscielska-Kasprzak K., Dadlez M., Otlewski J. (2001) Selection of potent chymotrypsin and elastase inhibitors from M13 phage library of basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1550, 153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li W., Wang B. E., Moran P., Lipari T., Ganesan R., Corpuz R., Ludlam M. J., Gogineni A., Koeppen H., Bunting S., Gao W. Q., Kirchhofer D. (2009) Pegylated Kunitz domain inhibitor suppresses hepsin-mediated invasive tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 69, 8395–8402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ley A. C., Guterman S. K., Markland W., Kent R. B., Roberts B. L., Ladner R. C. (2003) ITI-D1 Kunitz domain mutants as HNE inhibitors. U. S. Patent 003/0175919 A1, pp. 1–55

- 31. Salameh M. A., Soares A. S., Hockla A., Radisky D. C., Radisky E. S. (2011) The P2′ residue is a key determinant of mesotrypsin specificity, engineering a high affinity inhibitor with anticancer activity. Biochem. J. 440, 95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scheidig A. J., Hynes T. R., Pelletier L. A., Wells J. A., Kossiakoff A. A. (1997) Crystal structures of bovine chymotrypsin and trypsin complexed to the inhibitor domain of Alzheimer's amyloid β-protein precursor (APPI) and basic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI): engineering of inhibitors with altered specificities. Protein Sci. 6, 1806–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmidt A. E., Chand H. S., Cascio D., Kisiel W., Bajaj S. P. (2005) Crystal structure of Kunitz domain 1 (KD1) of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in complex with trypsin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27832–27838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Helland R., Leiros I., Berglund G. I., Willassen N. P., Smalås A. O. (1998) The crystal structure of anionic salmon trypsin in complex with bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Eur. J. Biochem. 256, 317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. García-Fernández R., Pons T., Perbandt M., Valiente P. A., Talavera A., González-González Y., Rehders D., Chávez M. A., Betzel C., Redecke L. (2012) Structural insights into serine protease inhibition by a marine invertebrate BPTI Kunitz-type inhibitor. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Antuch W., Berndt K. D., Chávez M. A., Delfín J., Wüthrich K. (1993) The NMR solution structure of a Kunitz-type proteinase inhibitor from the sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus. Eur. J. Biochem. 212, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gil D., García-Fernández R., Alonso-del-Rivero M., Lamazares E., Pérez M., Varas L., Díaz J., Chávez M. A., González-González Y., Mansur M. (2011) Recombinant expression of ShPI-1A, a non-specific BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitor, and its protection effect on proteolytic degradation of recombinant human miniproinsulin expressed in Pichia pastoris. FEMS Yeast Res. 7, 575–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. García-Fernández R., Pons T., Meyer A., Perband M., González-González Y., Gil D. F., Chávez M. A., Betzel C., Redecke L. (2012) Crystal structure of the recombinant BPTI-Kunitz-type inhibitor rShPI-1A from the marine invertebrate Stichodactyla helianthus. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 68, 1289–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Estell D. A., Graycar T. P., Miller J. V., Powers D. B., Wells J. A., Burnier J. P., Ng P. G. (1986) Probing steric and hydrophobic effects on enzyme-substrate interactions by protein engineering. Science 233, 659–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Erlanger B. F., Kokowsky N., Cohen E. (1961) Preparation and properties of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 95, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakajima K., Powers J. C., Ashe B. M., Zimmerman M. (1979) Mapping the extended substrate binding site of cathepsin G and human leukocyte elastase: studies with peptide substrates related to the α1-protease inhibitor reactive site. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 4027–4032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. DelMar E. G., Largman C., Brodrick J. W., Geokas M. C. (1979) A sensitive new substrate for chymotrypsin. Anal. Biochem. 99, 316–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chase T., Jr., Shaw E. (1967) p-Nitrophenyl-p′-guanidinobenzoate HCl: a new active site titrant for trypsin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 29, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Copeland R. A., Lombardo D., Glannaras J., Decicco C. P. (1995) Estimating Ki values for tight binding inhibitors from dose-response plots. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 5, 1947–1952 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bieth J. G. (1995) Theoretical and practical aspects of proteinase inhibition kinetics. Methods Enzymol. 248, 59–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leatherbarrow R. J. (2009) GraFit Version 7, Erithacus Software Ltd., Horley, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yanes O., Villanueva J., Querol E., Aviles F. X. (2007) Detection of non-covalent protein interactions by “intensity fading” MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: applications to proteases and protease inhibitors. Nat. Protoc. 2, 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server, in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M., ed) pp. 571–607, Humana Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 50. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Würtele M., Hahn M., Hilpert K., Höhne W. (2000) Atomic resolution structure of native porcine pancreatic elastase at 1.1 Å. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 520–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lüthy R., Bowie J. U., Eisenberg D. (1992) Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature 356, 83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vriend G. (1990) WHAT IF, a molecular modeling and drug design program. J. Mol. Graph. 8, 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eyal E., Gerzon S., Potapov V., Edelman M., Sobolev V. (2005) The limit of accuracy of protein modeling: influence of crystal packing on protein structure. J. Mol. Biol. 351, 431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. DeLano W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (2002) DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vedvick T., Buckholz R. G., Engel M., Urcan M., Kinney J., Provow S., Siegel R. S., Thill G. P. (1991) High-level secretion of biologically active aprotinin from the yeast Pichia pastoris. J. Ind. Microbiol. 7, 197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kjeldsen T., Brandt J., Andersen A. S., Egel-Mitani M., Hach M., Pettersson A. F., Vad K. (1996) A removable spacer peptide in a α-factor-leader/insulin precursor fusion protein improves processing and concomitant yield of the insulin precursor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 170, 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peanasky R. J., Bentz Y., Paulson B., Graham D. L., Babin D. R. (1984) The isoinhibitors of chymotrypsin/elastase from Ascaris lumbricoides: isolation by affinity chromatography and association with the enzymes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 232, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zani M. L., Nobar S. M., Lacour S. A., Lemoine S., Boudier C., Bieth J. G., Moreau T. (2004) Kinetics of the inhibition of neutrophil proteinases by recombinant elafin and pre-elafin (trappin-2) expressed in Pichia pastoris. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2370–2378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Apostoluk W., Otlewski J. (1998) Variability of the canonical loop conformations in serine proteinases inhibitors and other proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 32, 459–474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]