Abstract

Aims

Estimating the effect of a nursing intervention in home-dwelling older adults on the occurrence and course of delirium and concomitant cognitive and functional impairment.

Methods

A randomized clinical pilot trial using a before/after design was conducted with older patients discharged from hospital who had a medical prescription to receive home care. A total of 51 patients were randomized into the experimental group (EG) and 52 patients into the control group (CG). Besides usual home care, nursing interventions were offered by a geriatric nurse specialist to the EG at 48 h, 72 h, 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days after discharge. All patients were monitored for symptoms of delirium using the Confusion Assessment Method. Cognitive and functional statuses were measured with the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Katz and Lawton Index.

Results

No statistical differences with regard to symptoms of delirium (p = 0.085), cognitive impairment (p = 0.151), and functional status (p = 0.235) were found between the EG and CG at study entry and at 1 month. After adjustment, statistical differences were found in favor of the EG for symptoms of delirium (p = 0.046), cognitive impairment (p = 0.015), and functional status (p = 0.033).

Conclusion

Nursing interventions to detect delirium at home are feasible and accepted. The nursing interventions produced a promising effect to improve delirium.

Key Words: Delirium, Nursing intervention, Home-dwelling older adults, Pilot study, Prevention

Introduction

Delirium is a mental disorder of acute onset and fluctuating course, characterized by variable disturbances in consciousness, orientation, memory, thought, perception, and behavior [1]. Acute illness and adverse medication reactions can cause delirium among older adults. It is the most observed acute cognitive impairment among older individuals [2]. High levels of nondetection of delirium during hospitalization with the consequence of nontreatment have been reported [3]. Results show that one third of all older patients still have unresolved delirium symptoms when they return home [4]. The overall prevalence of delirium among home-dwelling older adults has been estimated between 0.5 and 34%, but there is a lack of well-documented population-based studies [5].

Delirium is considered to be a reversible condition if detected early, and the literature indicates that prompt detection of delirium risk factors can avoid its occurrence in many cases [6]. Undetected and untreated delirium can have serious consequences for older adults such as cognitive and physical decline, rehospitalization, institutionalization or premature mortality [7,8]. A preventive approach to delirium, including the detection of risk factors by community health nurses, may contribute to significantly maintain or restore health among vulnerable older adults [9]. Overall, little research has been done on delirium management among home-dwelling older patients after hospital discharge, and to our knowledge, patient-centered nursing preventive interventions in this setting are lacking [10].

The aim of this pilot study was to estimate the effect of an innovative nursing intervention to detect and/or to prevent delirium among discharged older adults receiving home health care. Three hypotheses were compared between older adults who receive the usual care and those who receive the nursing preventive intervention over a 1-month period, the latter group showing a significantly larger: (a) decrease in delirium symptoms as measured by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM); (b) decrease in cognitive impairment as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and (c) increase in functional independency as measured by the Katz and Lawton Index of activities of daily living (ADL)/instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

Materials

Design, Setting, and Sample

The nonexistence of a nursing intervention to detect and improve delirium among home-dwelling older adults justifies the conduct of a pragmatic randomized pilot trial. It was conducted in the French part of Switzerland from February to November 2012 in collaboration with a home health care center. However, to conduct a pilot study, no sample calculation needed to be applied [11]. This study recruited an almost equal sample size to the little studies of delirium prevention in hospital settings [12,13].

The regional ethics committee for research approved the research protocol (CCVEM 030/11). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the closest relatives for those with <15 points on the MMSE. Patients with a medical prescription for home health care were eligible to participate if they were: (a) aged ≥65 years; (b) recently discharged from hospital, and (c) capable of understanding and answering questions in French. They were excluded if they had: (a) outpatient treatment still going on within the hospital premises; (b) a medical prescription for a single intervention of home health care, and (c) if they were outside the study reach.

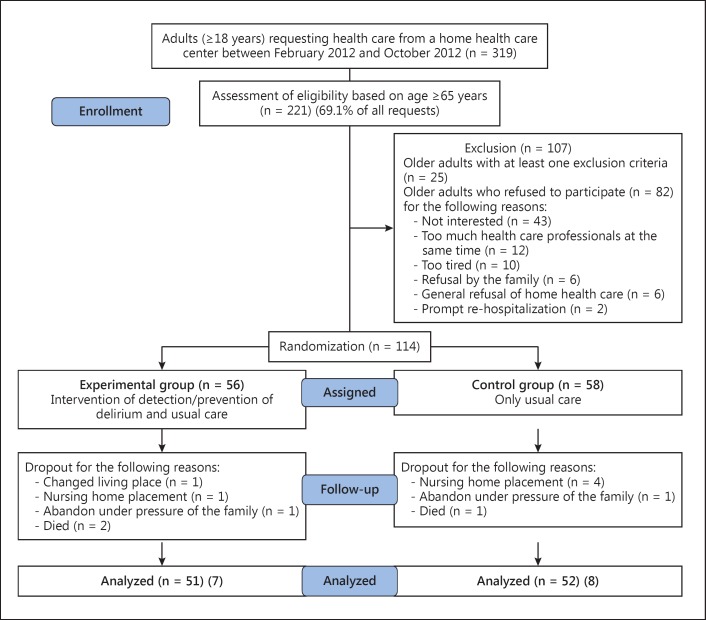

A convenience sample of 221 eligible participants were contacted to participate. For different reasons, 107 older adults refused to participate, resulting in a total of 114 participants who were randomized by the principal investigator (PI) to an experimental group (EG; n = 56) and a control group (CG; n = 58). A blocked randomization scheme with sealed envelopes was applied. This procedure revealed to be appropriate to obtain an equilibrated enrollment in both arms. At the end, 51 participants in the EG and 52 participants in the CG completed the study (fig. 1). Data on delirium, delirium risk factors, cognition, physical status, comorbidities, usual care home visits, and medication treatment were collected.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment of the participants.

Participants

Control Group

Participants in the CG received only the usual home care but were assessed for delirium symptoms at the study entry (M1), after 1 month (M2), and in patient records during the study period. The amount of usual care depended on the patient's clinical status, the presence of informal caregivers, and the skill mix within the nursing workforce of the home health care center. The community health nurses conducted a total of 484 usual care visits during the study period, with an average of 2.28 (SD = 0.84) weekly visits per participant.

Intervention Group

In addition to the usual care and delirium symptoms assessment mentioned before, each participant in the EG received 5 additional patient-centered nursing interventions. The community health nurses conducted a total of 452 usual care visits during the study period, with an average of 2.26 (SD = 1.34) weekly visits per participant. The construction of the nursing intervention was based on the theoretical framework of the prevention strategies from the Neuman System Model [14] and from the Mapping Intervention Model of Bartholomew et al. [15]. It was completed with recommendations from different recent evidence-based guidelines as well as from geriatric-friendly hospital recommendations [15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

All nursing interventions were dispensed by the research geriatric clinical nurse during their home visits. This research nurse was trained by the PI over 3 days with the aim to assess delirium symptoms with the CAM and the health status of the participants, and to apply the 5 person-centered nursing interventions. These 5 interventions were structured according to 6 domains (assessment, detection, monitoring, support, dispensed care, health promotion, and education), 15 nursing intervention protocols, and covered 70 nursing activities (table 1). The interventions had been judged previously and accepted by a panel of community nursing experts. Furthermore, the nursing interventions were adapted and standardized after being pretested with 5 discharged home-dwelling older patients. A user guide was developed with the aim to structure and standardize application by the research certified graduate nurse (CGN). This procedure permitted the interventions to be patient-centered during the home visits by selecting the most appropriate domains, nursing activities, and nursing protocols in relation to the clinical status of the older adults and the presence/absence of delirium symptoms or risk factors [17].

Table 1.

Summary of 15 patient-centered multi-component nursing interventions protocols at home

| Clinical assessment after hospitalization | Nurse-led intervention | Protocol | Usual home care protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium risk factor rate | Assessment of delirium risk factors among the discharged older patient. | Applying the clinical assessment checklist | None |

| Cognitive impairment and/or disorientation after hospitalization | Provide lighting, signs, calendars and clocks. Reorientation of the individual to time, place and person. Introduce cognitively stimulating activities such as reminiscence, preferred music or storytelling. | Orientation and cognitive therapeutic activities | None |

| ADL/IADL performance and needs of assistance at home | Encourage accepting aid and assistance for the ADL/IADL activities with the aim to find independency for daily activities of living as quickly as possible. Balance between autonomy/privacy and assistance. | ADL/IADL assistance | None |

| Dehydration | Encourage to drink at least 1.5 l parenteral fluids. Use mouth dehydration assessment to assess dehydration. | Hydration | None |

| Post-discharge constipation | Encourage fluid intake, fiber-enriched alimentation and mobility, especially among post-surgery opioid-treated older adults to restore daily toilet visit. | Anticonstipation after hospitalization | None |

| Hypoxia | Assess for hypoxia with portable saturation device. Encourage regular physical activities to enhance pulmonary capacities. | Hypoxia protocol based on EBP in hypoxia in the home care setting | None |

| Post-discharge immobility or limited mobility | Encourage mobility and outside walks. Use walking aids to prevent falls. Develop a daily and weekly mobility program in collaboration with informal caregivers and physiotherapist. | Mobilization protocol | None |

| Infection prevention | Regular assessment for pulmonary, urine tract, skin and other infections. Implement health education and promotion to prevent/detect infections. | Monitoring of infections Use assessment/prevention of skin, urinary tract and pulmonary infections | None |

| Polymedication, over-the-counter medications and alcohol abuse | Review medication for type and number of medications. Health education and promotion of the danger of auto-medication, over-the-counter medication, psychoactive medication, analgesia and alcohol use. | Psychoactive medication and healthy aging protocol | None |

| Post-discharge pain | Assess for pain at each home visit, inform informal caregivers of the importance to treat pain. | Pain management protocol | None |

| Nutrition at home | Encourage to consume equilibrated meals 3 times a day. Propose in collaboration with the informal caregivers’ assistance to prepare meals or to use the home-meal delivery service. Encourage regularly dentist visits. | Equilibrated feeding protocol | None |

| Sensory impairment | Resolve reversible cause of the sensory impairment. Ensure that hearing and visual aids are available, working and used by those who need them. | Vision protocol Hearing protocol | None |

| Sleep disturbance | Avoid nursing procedures and medication schedule during sleep. Reduce the number of visits late at evenings and avoid noise during the night. | Sleep enhancement protocol | None |

| Securing living environment at home | Assessment of fall risk by an occupational therapist. Eliminate all potential risks to fall such as carpets and steps. Equip the bathroom with aids to facilitate toilet use, bathing and showering | Security and fall prevention protocol at home | None |

| Reinforcing social network | Prevent loneliness and social isolation. Encourage communication, social network propositions and visits of close friends without overstimulating. | Social network protocol | None |

Each intervention started with an assessment of the physical and cognitive status of the patient including the CAM, pain, and biologic parameters such as blood pressure, temperature, heart rate, glycemia, oxygen saturation, and pain evaluation. In addition, delirium risk factors were also assessed such as constipation/diarrhea, dehydration, infections, and additionally prescribed/over-the-counter medications. Subsequently, the nursing interventions provided took into consideration the assessed health status and delirium risk factors. Finally, each intervention was concluded with 2 or 3 oral health promotion recommendations to the participant and informal caregiver. The first intervention was made within 2 days after having received consent of the participants. Interventions 2-5 were conducted at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after their consent. This interval was based on the average duration of a delirium episode, which usually varies between 3 and 7 days [2].

Data Collection

Two assessment visits were planned for all participants at an interval of 30 days (M1 and M2). The full investigation took place during M1, and the PI collected data by using patient records and patient interview. Before each patient-centered nursing intervention, delirium symptoms/signs were assessed with the CAM by the CGN. During the study period, the PI assessed the fluctuation of the cognitive status in all participants with the CAM using patient records. At M2, the PI assessed the health status evolution of the participants using the CAM, the MMSE and the ADL/IADL. The health data collected by the PI and the CGN were blinded to the treatment conditions and the previous data. During the study period, the treatment fidelity and the amount of the planned usual care was followed up in both groups.

Dependent Variables

Delirium Symptoms

Delirium was assessed using the French version of the CAM [22,23]. The CAM is a 9-item instrument developed to assist clinicians who have no formal psychiatric training used to quickly and accurately identify delirium in patients. The CAM was compared with other instruments and found to have the best combination of ease and speed of use, reliability and validity [24]. It has been considered suitable for bedside use to identify patients with delirium. The research nurse filled in the CAM after a structured interview. The delirium symptoms/signs assessed were: (a) sudden onset or fluctuating course of disorientation; (b) inattention; (c) disorganized thoughts; (d) altered level of consciousness; (e) disorientation; (f) memory impairment; (g) perceptual disturbances; (h) psychomotor agitation/retardation, and (i) altered sleep-wake cycle.

Delirium was assessed and documented by clinically observing the 9 symptoms/signs described in the CAM. Afterwards, the collected data were analyzed dimensionally as this is sometimes considered less arbitrary than a categorical analysis (delirium vs. no delirium), especially when psychopathology or behavior are best observed as a dimensional condition [25]. Moreover, older adults can have a subsyndrome delirium without presenting all the criteria for a delirium diagnostic after having been discharged. Consequently, we used the dimensional clinical observation that increases the detection of delirium and its symptoms [26,27,28]. CAM scores were assessed at M1, before the patient-centered interventions in the EG, in patient records, and at M2. A well satisfactory interrater ratio was obtained between the PI and the CGN concerning the assessment of the CAM with a Cohen's kappa of 0.79 [29].

Cognitive Assessment

The cognitive level was assessed using the MMSE [30,31] by regrouping the 7 domains of cognitive functioning. The 11-item instrument measures orientation, memory, language, and psychomotor skills. The sum of the scores varies from 0 (severe cognitive impairment) to 30 (no cognitive impairment). A score of <24 points was considered as the cutoff point for cognitive impairment. The MMSE was mostly assessed by the PI, and the instrument presented good psychometric proprieties [32]. An excellent interrater ratio was obtained between de PI and the CGN with an intraclass correlation of 0.92.

Functional Assessment

Several studies reported that the functional status of home-dwelling older adults is most appropriately assessed by adding the scores of autonomy in the ADL/IADL [33,34]. This study adopted this approach and assessed the functional status by adding the scores of the Katz Index of ADL [35] and the Lawton Index of IADL [33,36]. The ADL scale is a well-established and documented tool [37] used to assess independency versus dependency in the areas of bathing, dressing, transfer, toileting, incontinence, and feeding. The IADL scale assesses independency versus dependency in more complex areas of daily living such as: using the telephone; shopping; preparing meals; cleaning and laundry; using public transport; management of medication and finances, and the maintenance of the house [38]. The ADL/IADL was mostly assessed by the PI and sometimes by the CGN, and an excellent interrater ratio was obtained between the PI and the CGN with a Cohen's kappa of 0.85.

Other Variables

The participants' sociodemographic characteristics (table 2) and confounding variables were collected from the patients' home care chart. Based on the systematic review of the NICE team [20], 4 confounding variables, i.e. age, cognitive impairment (MMSE), polymedication (number of medication) and comorbidities [Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) rate], have been used to adjust our results (table 3).

Table 2.

Basic assessment of sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and delirium risk factors of the participants

| Variables | EG (n = 51) | CG (n = 52) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Average | 82.92 (6.73) | 83.50 (7.62) | 0.249a |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 33 (64.6) | 34 (65.4) | 0.942b |

| Civil state | 0.664c | ||

| Single | 3 | 3 | |

| Married/partner | 21 | 18 | |

| Divorced/separated | 4 | 2 | |

| Widowed | 23 | 29 | |

| Living with | 0.624c | ||

| Partner/spouse | 23 | 15 | |

| Close family member | 6 | 4 | |

| Education | 0.158b | ||

| Primary | 3 | 10 | |

| Secondary | 20 | 18 | |

| Professional | 19 | 13 | |

| University | 9 | 11 | |

| Raison for home health care | |||

| Accident | 13 (25.5) | 14 (26.9) | |

| Illness | 38 (74.5) | 36 (69.2) | |

| Respite care informal caregivers | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.353a |

| Usual care home visits | |||

| Average | 2.26 (1.34) | 2.28 (0.84) | 0.916a |

| Health status – comorbidities | |||

| Average delirium symptoms | 2.71 | 2.38 | 0.395a |

| Average MMSE | 23.96 | 23.81 | 0.873a |

| IQCODE | 3.69 | 3.67 | 0.895a |

| ADL/IADL functional status | 32.16 | 32.02 | 0.938a |

| CIRS-G | 13.45 | 14.04 | 0.354a |

| Depression GDS-30 | 9.10 | 8.32 | 0.432a |

| Nutritional status – BMI | 23.62 | 23.26 | 0.678a |

| Pain assessment – EVA | 2.73 | 3.37 | 0.367a |

| Pharmacological delirium risk factors | |||

| Average number of medication | 6.22 (2.87) | 6.42 (2.69) | 0.706a |

| Delirium high risk medicationd | 1.16 (1.20) | 1.06 (1.03) | 0.655a |

| Delirium medium risk medicationd | 0.71 (0.67) | 0.69 (0.85) | 0.929a |

| Delirium uncertain risk medicationd | 4.35 (2.37) | 4.63 (2.29) | 0.541a |

| Nonpharmacological delirium risk factors | |||

| Urinary in-dwelling catheter/wound | 16 (31.4) | 18 (34.6) | 0.726c |

| Conflict with partner/spousee | 29 (56.9) | 25 (48.1) | 0.372c |

Figures are SD or percentages.

Student's t test.

Fisher's exact test.

Pearson's χ2 test.

Following the American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel.

Information mentioned in the patient record.

Table 3.

Distribution of delirium symptoms among participants between M1 and M2

| Delirium symptoms | M1 |

p value | M2 |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG (n = 51) | CG (n = 52) | EG (n = 51) | CG (n = 52) | |||

| 0 symptom | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 | ||

| 1 symptom | 11 | 15 | 18 | 10 | ||

| 2 symptoms | 12 | 9 | 10 | 14 | ||

| 3 symptoms | 8 | 8 | 12 | 12 | ||

| 4 symptoms | 6 | 8 | 0.668a | 1 | 4 | 0.337a |

| 5 symptoms | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6 symptoms | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 7 symptoms | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 symptoms | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

Fisher's exact test.

The PI assessed the general health status of the patients. More precisely, comorbidity was measured using the CIRS-G [39], depression with the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [40], dementia with the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) filled out by a close family member [41], pain using the EVA [42], and nutritional status using the BMI [43]. Prescribed medications, hospitalizations in the previous year, and nonpharmacological delirium risk factors were assessed using the patients' chart. For this study, an assessment tool was developed as a checklist [44]. Table 4 presents the health status and the delirium risk factors of the participants.

Table 4.

Outcomes of dependent variables before and after a nursing intervention to prevent and detect delirium symptoms among discharged home-dwelling older adults

| Outcomes | EG (n = 51) | CG (n = 52) | p value | p value after adjustment for confounding variablesg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium symptoms | 1.90 ± 1.56a | 2.50 ± 1.90 | 0.084d | 0.046g,* |

| Cognitive impairment | 25.06 ± 3.63b | 23.81 ± 5.04 | 0.152e | 0.015g,* |

| Functional impairment | 29.16 ± 8.53c | 31.31 ± 9.71 | 0.235f | 0.033g,* |

p < 0.05.

Mean number of symptoms ± SD.

Difference in the MMSE.

Mean score ± SD on the ADL/IADL.

Mann-Whitney U test.

t test for independent samples.

Confounding variables: age, polymedication, cognitive impairment, and comorbidities.

ANCOVA for the confounding variables cognitive impairment (MMSE), age, comorbidities, and polymedication.

Data Analysis

Comparisons between and within the groups were performed and the statistical tests were selected depending on the type of the variables. Baseline characteristics, delirium symptoms, and cognitive and functional impairment were compared between the EG and the CG using Fisher's exact and Student's t tests. The number of delirium symptoms were counted and compared between the interventions, the usual care and M1 and M2 for both groups.

To estimate the effect of the interventions, Student's t tests for paired and independent samples were used. Covariance analyses (ANCOVA) were performed to adjust the outcomes for confounding variables (age, cognitive impairment, polymedication, and comorbidities). All statistical tests were done with the IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS®) version 21 [45]. Statistical significance was established at p = 0.05 with all tests being two-tailed. Confirmed analysis approaches were used to assess the delirium symptoms/signs with the CAM, documented in the patient records after providing usual care by the community health nurses [46,47]. Qualitative data to assess feasibility and acceptability were summarized using content analysis [48,49].

Results

EG and CG did not differ significantly in sociodemographic characteristics, health status or delirium risk factors. The majority of the participants in both groups were composed of widowed female older adults (>82 years), living alone, with a primary or professional education level. Loss of independency after an acute illness was the most important reason for home health care. The health status of the older participants showed the presence of comorbidities, elevated means of symptoms and signs of cognitive impairment, delirium and depression, polymedication (up to >6 medications daily), and the presence of stress due to conflictual situations (table 4).

Distribution and Evolution of the Delirium Symptoms

The EG and the CG did not differ significantly between M1 and M2. However, the number of participants with ≥4 delirium symptoms in the EG decreased substantially (16 vs. 4) at M2 compared with those in the CG (14 vs. 10; table 2).

Delirium Signs/Symptoms

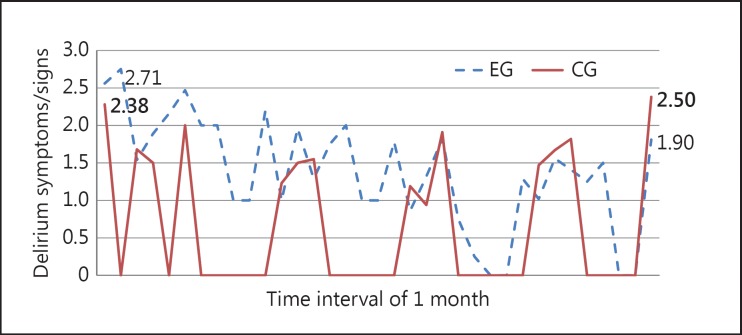

As expected and largely documented in the literature [2], delirium symptoms/signs fluctuated largely in both groups. However, a substantial decrease in the delirium symptoms was observed in the whole EG during the study period and at M2, but less in the CG in which the delirium symptoms even increased at M2. During the study period, 798 delirium assessments with the CAM were conducted in the EG and 588 in the CG (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Number and evolution of CAM scores among the participants of the EG and the CG during the study period. Average of delirium symptoms/signs during the study period in the EG (n = 51) and CG (n = 52). 798 delirium assessments in the EG (244 assessments during the interventions, 452 delirium assessments during usual care, 51 delirium assessments during M1, and 51 delirium assessments during M2); 588 delirium assessments in the CG (484 assessments during usual care, 52 assessments during M1, and 52 delirium assessments during M2).

There were no statistically significant differences in the mean scores between the EG and CG at M2 (p = 0.085), although a promising effect in the direction of our hypothesis of the nursing intervention strategy at M2 on the CAM scores in the EG compared to the CG (p = 0.395 vs. 0.085; table 3) was observed. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the EG with a score of 2.71 at M1 versus a score of 1.90 at M2 (p = 0.003), but no statistically significant difference was found in the CG (2.36 vs. 2.50; p = 0.781).

The potential influence on the CAM scores of covariates such as MMSE, polymedication, age, and CIRS-G were calculated. A significant difference in the mean scores of the MMSE between the EG and the CG (p = 0.046; table 3) was found. More severe cognitive impairment, as measured by the MMSE at M1, was associated with higher CAM scores at M2 (p = 0.000) (online suppl. table 5 and 5a; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000375444 for all online suppl. material).

Cognitive Functioning

There was no statistically significant difference between the EG and CG, neither at M1 (p = 0.873) nor at M2 (p = 0.152; table 3), in cognitive functioning. However, the evolution of the mean scores of the MMSE between M1 and M2, with a significant difference being observed in the EG (p = 0.005) as opposed to the CG (p = 1.000).

The covariate analysis herein revealed the influence of the confounding variables cognitive impairment, polymedication, age, and comorbidities on the MMSE scores at M2. A statistical difference was found in the mean scores of the MMSE between the EG and the CG (p = 0.015; table 3). The lower the MMSE score at M1 the lower the improvement at M2 (p = 0.000) (online suppl. table 6 and 6a).

Functional Status

No statistically significant difference was found for the ADL/IADL scores between the groups at M1 (p = 0.938) and M2 (p = 0.235; table 3). However, a significant improvement of ADL/IADL performance between M1 and M2 was seen for the EG (p = 0.000) as opposed to the CG (p = 0.348).

A covariance analysis was also performed using the confounding variables MMSE, polymedication, age, and CIRS-G on ADL/IADL scores at M2. We found a statistical difference in the mean ADL/IADL scores between the EG and the CG (p = 0.033; table 3). The more ADL/IADL and comorbidity rates were important at M1, the more difficult it was for the patients to recuperate functional impairment at M2 (ADL/IADL at M1, p = 0.000; comorbidities at M1 p = 0.013) (online suppl. table 7 and 7a).

Feasibility and Acceptability of the Intervention and the Study

Study

A 6-month recruitment strategy was effective with a total of 196 eligible older adults; 58% (113/196) agreed to participate and the overall retention rate reached 91% (103/113). The computerized blocked randomization with opaque sealed envelopes containing the group assignments was adequate to allocate comparable participants in the EG and the CG. The time needed to fill in the instruments for the health status and the delirium risk factors at M1 and M2 varied between 30 and 210 min (mean = 75 min) at M1 and between 23 and 150 min (mean = 39 min) at M2. The time to fill in the CAM using the patient records varied between 15 and 35 min (mean = 21 min). Data on health behavior, health status, treatments, frequency of planned care, hospitalizations, institutionalization, and deaths were available through patients' home care records. The transcriptions of the observation notes of the home care nurses were incomplete for 77% of the patients.

Intervention

A total of 244 patient-centered nursing interventions were conducted for the 51 participants of the EG: 44 received 5 nursing interventions, 3 received 4, and 4 received 3 (fig. 1). The duration of the interventions varied between 5 and 180 min (mean = 59.8 min; table 5). The participants and their informal caregivers accepted all interventions (n = 244). The home care nurses mentioned the positive feedbacks they received from the EG participants who indicated that the nursing interventions did not cause security issues or any physical (falls) or psychological (increasing anxiety) events. Almost all participants and their informal caregivers in the EG (44/51) expressed that the interventions generated benefits during posthospitalization. A total of 106 (43%) interventions were made in the morning (8-12 a.m.) versus 138 (57%) in the afternoon (1-7 p.m.). No difficulty was observed during these interventions including problems of intensity in the health promotion or health education activities or physical fatigue/exhaustion. An important barrier for the patient-centered nursing interventions to participants with mobility impairment was related to clutter living spaces with unfixed carpets and inaccessible elevators. In addition, participants with advanced cognitive and hearing impairments or multiple delirium symptoms/signs needed the presence of an informal caregiver or family member to receive adapted interventions.

Table 5.

Duration of the patient-centered nursing interventions

| Intervention | Duration, min |

p value1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | max | mean (SD) | 95% CI | ||

| Intervention 1 | 10 | 120 | 66.4 (25.7) | 57.6 – 72.3 | – |

| Intervention 2 | 10 | 120 | 61.4 (24.6) | 55.3 – 0.1 | 0.004* |

| Intervention 3 | 5 | 180 | 59.1 (31.6) | 50.9 – 69.8 | 0.002* |

| Intervention 4 | 5 | 120 | 55.5 (23.8) | 49.4 – 64.0 | 0.013 |

| Intervention 5 | 5 | 150 | 54.0 (27.3) | 45.7 – 62.3 | 0.027 |

Bonferroni correction of the p value.

Significant with a p value <0.013.

Discussion and Conclusion

This randomized pilot trial is the first attempt to detect and recover delirium among discharged home-dwelling older adults using a tailor-made patient-centered nursing intervention. Results are promising; they suggest that the nursing intervention leads to a decrease in delirium symptoms/signs in older adults when compared to usual home care [50]. This represents a breakthrough in home health care research, protecting frail older adults at home after a hospitalization or acute illness from developing delirium.

The different facets of the patient-centered home nursing care intervention, including the general follow-up, monitoring of medication use, health promotion, health education, encouragement and stimulation of ADL/IADL, and self-care, as well as the support of the informal caregivers may explain this effect. The number of delirium symptoms/signs decreased during the study period among the participants in the EG with at least 1 delirium symptom/sign at M2 compared to the participants in the CG. Furthermore, the cognitive status of the participants in the EG improved when compared to that in the CG. These findings highlight the fact that when adequate nursing is provided, enhanced (at least partially) reversibility of cognitive impairment among older patients after hospitalization can be observed. Although the assessment of delirium symptoms/signs with the CAM, using clinical patient records, showed to be accessible, there is a risk of delirium underdetection by incomplete clinical observations in the patient records. Further studies should explore innovative strategies to collect daily health data among home-dwelling older adults at risk or with delirium symptoms/signs.

Similarly to the delirium and cognitive improvement, the intervention substantially increased ADL/IADL performance in the EG group that contrasts with an only slight increase in the CG. However, IADL were less likely to improve, maybe due to more persistent executive impairment as suggested elsewhere [51].

Improving physical and mental health of discharged older adults contributes to their chances to remain at home in the best possible health condition. This may not only be beneficial on the individual level but also on the public health policy level. This will allow a maximal number of older adults to stay at home as long as possible, even after a delirium episode. However, there are no similar studies to support this statement. Nevertheless, the patient sample of this study may be quite representative of elderly subjects prone to developing delirium. Thus, the average age among the participants was representative of that of older adults requesting home health care in Switzerland [52]. A third of the participants presented significant cognitive impairment at M1, which corroborates recent results from other studies [53,54]. Almost all the participants had functional impairment at M1, which corroborates the results of recent studies on functional impairment among discharged older adults and showed an important patient vulnerability and care needs, as well as a high prevalence of multifactorial delirium risk factors [55,56]. These findings suggest that older patients are at a high risk of developing physical and cognitive deterioration during or after hospitalization; hospitalization should be considered an important delirium risk factor. As a consequence, limiting physical and cognitive decline during hospitalization may be an effective delirium prevention strategy [13].

Concerning the strengths of this clinical nurse-led intervention study, a very low dropout rate was observed, which suggests high interest, motivation, and care need levels of the participants and their informal caregivers. As participants, informal caregivers, and community health care nurses expressed their satisfaction and acceptability of the different components and the dose of the intervention strategy, it appeared to be feasible and well acceptable. Furthermore, the dimensional approach in conducting nurse-led research to detect and analyze delirium symptoms/signs and to consider the clinical features of subsyndrome delirium could be a very promising approach to optimize the detection of delirium in different health care settings. Similarly, and complementary to what was mentioned before, informal caregivers could play a key role in documenting symptoms and signs of delirium at home after discharge from hospital [57].

The use of the CAM may be a minor shortcoming, as it has not been validated among home-dwelling older adults [27]. The assessment of delirium symptoms/signs with the CAM using clinical patient records seems feasible; however, there is a risk of delirium underdetection by incomplete records. Due to overlapping symptomatology, subsyndromal delirium may have been confounded with other cognitive disorders [58]; the sample size is also minimal. Thus, this pilot study should be replicated by a statistically full-powered multisite study to confirm the effectiveness of our nursing intervention built in order to detect, prevent, and improve delirium after hospital discharge among home-dwelling older adults. This trial now allows calculating the sample size for a full-powered clinical trial by including a clinical difference of two delirium symptoms, a β of 0.80 (bilateral, two-tailed), an effect size of 0.34, and an α of 0.05. In this scenario, at least 134 participants are needed in each group. Increasing the effect size to 0.50 while keeping similar parameters would require a sample size of at least 75 participants in each group to detect an effect of the intervention.

This pilot study offers the first evidence of the beneficial effect of a nurse-led patient-centered nursing intervention to improve delirium at home. Participants, caregivers, and home care nurses expressed satisfaction and acceptability at the different stages of the study, and the dose of the intervention appeared to be feasible. This promising result is an innovated breakthrough to enhance and prevent the devastating consequences of delirium among home-dwelling older adults. This substantial innovation presents a major potential to develop similar research projects in collaboration with informal caregivers and community health care workers with the final aim: keeping older adults at home in an optimal health condition.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their participation in this study. This work would not have been possible without the input of Ms. Ariane Kapps, a Master of Science student, who helped with the development of the intervention, as well as that of all the participating nurses of the Home Health Care service of Valais. The authors also thank Ms. Sylvana Gerber for her contribution to the successful data collection of this work. This study was funded in part by the Leenaards Foundation, Swiss Alzheimer Association, Public Health Service of the State of Valais, and the University of Applied Sciences of Nursing La Source, Lausanne, Switzerland.

The sponsors played no role in the design and conduct of the study, data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, nor in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nussbaum AM. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. The Pocket Guide to the DSM-5 Diagnostic Exam. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383:911–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole MG, You Y, McCusker J, Ciampi A, Belzile E. The 6 and 12 month outcomes of older medical inpatients who recover from delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:301–307. doi: 10.1002/gps.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAvay GJ, Van Ness PH, Bogardus ST, Jr, Zhang Y, Leslie DL, Leo-Summers LS, et al. Older adults discharged from the hospital with delirium: 1-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1245–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fick DM, Mion LC. How to try this: delirium superimposed on dementia. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:52–60; quiz 1. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000304476.80530.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqi N, Holt R, Britton AM, Holmes J. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;4:10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S, Morandi A, Solberg LM, Schnelle J, et al. Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fick DM, Hodo DM, Lawrence F, Inouye SK. Recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia: assessing nurses’ knowledge using case vignettes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007;33:40–47. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070201-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bond SM. Delirium at home: strategies for home health clinicians. Alzheimers Care Today. 2009;10:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, Cheng J, Ismaila A, Rios LR, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milisen K, Foreman MD, Abraham IL, De Geest S, Godderis J, Vandermeulen E, et al. A nurse-led interdisciplinary intervention program for delirium in elderly hip-fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:523–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuman B, Fawcett J. ed 5. New York: Pearson Education; 2011. The Neuman Systems Model. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernandez ME. ed 3. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2011. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medical Research Council. London: Medical Research Council; 2008. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: New Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidani S, Braden CJ. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. Design, Evaluation, and Translation of Nursing Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hshieh TT, Chen P, Dowal S, Inouye SK. Knowledge-to-action for delirium prevention: diffusion of the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:S114. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010. Delirium: Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Registered Nursing Association of Ontario (RNAO) Toronto: Registered Nurses Association of Ontario; 2003. Screening for Delirium, Dementia and Depression in Older Adults. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laplante J, Cole MG, McCusker J, Singh S, Ouimet MA. Confusion Assessment Method. Validation of a French-language version. Perspect Infirm. 2005;3:12–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamis D, Sharma N, Whelan PJP, Macdonald AJD. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:543–555. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:823–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt NB, Kotov R, Joiner TE. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2004. Taxometrics: Toward a New Diagnostic Scheme for Psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraemer HC. Validity and psychiatric diagnoses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:138–139. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCusker J, Cole MG, Voyer P, Monette J, Champoux N, Ciampi A, et al. Use of nurse-observed symptoms of delirium in long-term care: effects on prevalence and outcomes of delirium. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:602–608. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voyer P, McCusker J, Cole MG, Monette J, Champoux N, Ciampi A, et al. Prodrome of delirium among long-term care residents: what clinical changes can be observed in the two weeks preceding a full-blown episode of delirium? Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1855–1864. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hair JKJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. ed 7. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.; 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derouesné C, Poitreneau J, Hugonot L, Kalafat M, Dubois B, Laurent B. Le mini-mental state examination (MMSE): un outil pratique pour l’évaluation de l’état cognitif des patients par le clinicien. Version française consensuelle. Presse Med. 1999;28:1141–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naugle RI, Kawczak K. Limitations of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Cleve Clin J Med. 1989;56:277–281. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.56.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buurman BM, van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, de Haan RJ, de Rooij SE. Variability in measuring (instrumental) activities of daily living functioning and functional decline in hospitalized older medical patients: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pol MC, Buurman BM, de Vos R, de Rooij SE. Patient and proxy rating agreements on activities of daily living and the instrumental activities of daily living of acutely hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1554–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gompertz P, Pound P, Ebrahim S. Validity of the extended activities of daily living scale. Clin Rehabil. 1994;8:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barberger-Gateau P, Commenges D, Gagnon M, Letenneur L, Sauvel C, Dartigues JF. Instrumental activities of daily living as a screening tool for cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly community dwellers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) Psychol Med. 1994;24:145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herr KA, Mobily PR. Comparison of selected pain assessment tools for use with the elderly. Appl Nurs Res. 1993;6:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(05)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corrada MM, Kawas CH, Mozaffar F, Paganini-Hill A. Association of body mass index and weight change with all-cause mortality in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:938–949. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greer N, Rossom R, Anderson P, MacDonald R, Tacklind J, Rutks I, et al. Washington: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. Delirium: Screening, Prevention, and Diagnosis – A Systematic Review of the Evidence. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.IBM Corporation. Somer: IBM Corporation; 2011. IBM-SPSS. Statistical Package for Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steis M, Fick DM. Delirium superimposed on dementia: accuracy of nurse documentation. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012;38:32–42. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110706-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voyer P, Cole MG, McCusker J, St-Jacques S, Laplante J. Accuracy of nurse documentation of delirium symptoms in medical charts. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14:165–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burla L, Knierim B, Barth J, Liewald C, Duetz M, Abel A. From text to codings: intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs Res. 2008;57:113–117. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313482.33917.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. ed 4. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2010. Measurement in Nursing and Health Research. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. ed 6. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc; 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodge HH, Kadowaki T, Hayakawa T, Yamakawa M, Sekikawa A, Ueshima H. Cognitive impairment as a strong predictor of incident disability in specific ADL-IADL tasks among community-dwelling elders: the Azuchi Study. Gerontologist. 2005;45:222–230. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.OBSAN. Recours aux services de soins à domicile Berne. 2012. http://www.obsan.admin.ch/bfs/obsan/fr/index/ [accessed June 15, 2013].

- 53.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, Fong TG, Gross A, Inouye SK, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:30–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoogerduijn JG, Buurman BM, Korevaar JC, Grobbee DE, de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ. The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 2012;41:381–387. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: ‘She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure’. JAMA. 2011;306:1782–1793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenbloom-Brunton DA, Henneman EA, Inouye SK. Feasibility of family participation in a delirium prevention program for hospitalized older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36:22–33. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100330-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voyer P, Richard S, McCusker J, Cole MG, Monette J, Champoux N, et al. Detection of delirium and its symptoms by nurses working in a long term care facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data