Abstract

We recently performed next generation sequencing (NGS) genetic screening in 11 consecutive and unrelated Tunisian HCM probands seen at Habib Thameur Hospital in Tunis in the first 6 months of 2014, as part of a cooperative study between our Institutions. The clinical diagnosis of HCM was made according to standard criteria. Using the Illumina platform, a panel of 12 genes was analyzed including myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3), beta-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), regulatory and essential light chains (MYL2 and MYL3), troponin-T (TNNT2), troponin-I (TNNI3), troponin-C (TNNC1), alpha-tropomyosin (TPM1), alpha-actin (ACTC1), alpha-actinin-2 (ACTN2) as well as alfa-galactosidase (GLA), 5′-AMP-activated protein (PKRAG2), transthyretin (TTR) and lysosomal-associated membrane protein-2 (LAMP2) for exclusion of phenocopies. Our preliminary data, despite limitations inherent to the small sample size, suggest that HCM in Tunisia may have a peculiar genetic background which privileges rare genes overs the classic HCM-associated MHY7 and MYBPC3 genes.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common inherited heart disease, caused by mutations in genes encoding for sarcomere proteins and transmitted in an autosomal dominant form.1 HCM is one of the most common causes of sudden cardiac death in the young and has been reported to have a 1:500 prevalence in the US and in Asia. However, the clinical profile of the disease in Africa has received little attention, with reports limited to Egypt and South Africa.2,3 In a recently published series of autopsy findings on juvenile sudden cardiac victims in Tunisia, HCM was diagnosed in 9 of 32 individuals (33%),4 suggesting an important burden of disease among young individuals in a country that is home to over 10 million inhabitants with complex ethnic background. The genetic basis of HCM in Tunisia, however, has not been previously explored.

We recently performed next generation sequencing (NGS) genetic screening in 11 consecutive and unrelated Tunisian HCM probands seen at Habib Thameur Hospital in Tunis in the first 6 months of 2014, as part of a cooperative study between our Institutions. The clinical diagnosis of HCM was made according to standard criteria.5 Using the Illumina platform, a panel of 12 genes was analyzed including myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3), beta-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), regulatory and essential light chains (MYL2 and MYL3), troponin-T (TNNT2), troponin-I (TNNI3), troponin-C (TNNC1), alpha-tropomyosin (TPM1), alpha-actin (ACTC1), alpha-actinin-2 (ACTN2) as well as alfa-galactosidase (GLA), 5′-AMP-activated protein (PKRAG2), transthyretin (TTR) and lysosomal-associated membrane protein-2 (LAMP2) for exclusion of phenocopies.

Overall, 8 mutations were identified in 5 of the 11 patients (45%). Of the 5 genotype-positive patients, 3 had single and 2 had double mutations (Table 1). Specifically, one patient had a mutation in MYH7, one in MYBPC3, one in MYL3, one was a TNNC1/ACTN2 double mutant and one in MYL2/TNNT2. All except one of the mutations were missense. In each case the mutation affected a highly conserved residue, and the genetic defect was considered pathogenic with high likelihood by the Alamut -1.5e software. Although this initial cohort is small, the low prevalence of the most common HCM-associated genes - MHY7 and MYBPC3 - is remarkable, and so is the presence of very rare genes such as TNNC1. For comparison, among the >600 probands genotyped in Florence, the combination of MHY7 and MYBPC3 and mutations accounted for >90% of identified mutations, and only one TNNC1 variant was identified in over 15 years.

Table 1.

Individual patient features.

| ID | Sex | Age | Gene | Mutation | Max LV thickness (mm) | Phenotype | Resting LV obstruction | Atrial fibrillation | Family history of HCM | Family history of sudden cardiac death | Symptoms | Events -Interventions |

| 1 | F | 49 | MYL3 | c.170 C>A (p.A57D) | 14 | End-Stage | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Chest pain Dyspnea | ICD (Primary prevention) |

| 2 | M | 47 | MYL2; TNNT2 | c.173 G>A (p.R58Q); c.634 C>T (R212W) | 33 | Massive LVH | Yes | No | Yes | No | Chest pain Palpitations | - |

| 3 | M | 61 | TNNC1; ACTN2 | c.23 C>T (p.A8V); c.1298 C>T (p.S433L) | 21 | Progressive decline in systolic function, pending end-stage | No | No | Yes | No | Chest pain Dyspnea | - |

| 4 | M | 53 | MYBPC3 | c.2413+1 G>A (p. ?) | 15 | Non obstructive | No | No | No | No | Palpitations | - |

| 5 | F | 60 | MYH7 | c.2792 A>C (p.E931A) | 21 | Mid-ventricular obstruction, Apical aneurysm | Yes | No | No | No | Chest pain Palpitations | Sustained VT |

| 6 | F | 80 | - | None | 17 | Classic HCM (septal LVH) | No | No | No | No | Dyspnea | - |

| 7 | M | 50 | - | None | 15 | Classic HCM (septal LVH). Microvascular ischemia | No | No | No | Yes | Chest pain | - |

| 8 | M | 38 | - | None | 20 | Microvascular ischemia | No | No | Yes | Yes | Chest pain | Pacemaker for AV block |

| 9 | F | 41 | - | None | 18 | Diastolilc dysfunction Non obstructive | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Palpitations Dyspnea | HF progression (NYHA Class III) |

| 10 | F | 65 | - | None | 27 | Classic HCM (septal LVH) | Yes | No | Yes | No | Chest pain | - |

| 11 | M | 39 | - | None | 20 | Biventricular hypertrophy | No | No | No | No | Mild dyspnea | - |

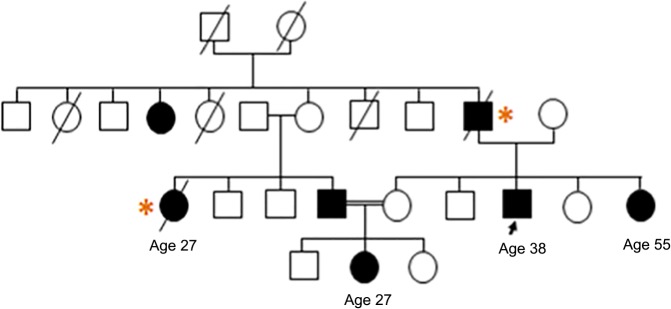

According to a consistent pattern in HCM history, early cohorts identified in each country belong to the most severe end of the disease spectrum, coming to attention in areas where awareness for the disease has not yet developed.6 Indeed, our patients had severe manifestations, including massive LVH, end-stage progression and recurrent family history of SCD (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, 2 of the 5 genotyped individuals had complex genotypes, a well-established marker of severity.7 In this context, the low representation of MHY7 and MYBPC3 mutations is even more unexpected, as these two genes are associated with the majority of severe phenotypes in other countries including – recently – Egypt,2 and are an almost constant feature of complex genotypes.7 In conclusion, these preliminary data, despite limitations inherent to the small sample size, suggest that HCM in Tunisia may have a peculiar genetic background which privileges rare genes overs the classic HCM-associated MHY7 and MYBPC3 genes. This hypothesis deserves further investigation, as it may importantly impact the epidemiology, phenotypic expression and severity of the disease in the region, including predisposition to sudden cardiac death.

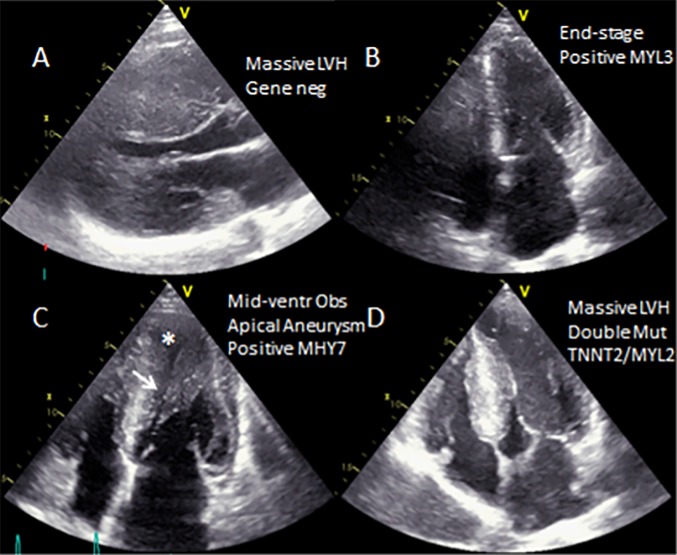

Figure 1.

Phenotypic spectrum. Morphologic features ranged from massive (A) to mild (B) LVH, to mid-ventricular obstruction (C-arrow) and apical aneurysm (asterisk) to classic septal LVH with dynamic LV outflow obstruction.

Figure 2.

Pedigree of patient 8 (arrow), showing autosomal dominant transmission of HCM and prevalence of sudden cardiac death (asterisks).

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Ommen SR, Semsarian C, Spirito P, Olivotto I, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: present and future, with translation into contemporary cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;8;64(1):83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassem HSh, Azer RS, Saber-Ayad M, Moharem-Elgamal S, Magdy G, Elguindy A, Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Yacoub MH. Early results of sarcomeric gene screening from the Egyptian National BA-HCM Program. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6(1):65–80. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falase AO, Ogah OS. Cardiomyopathies and myocardial disorders in Africa: present status and the way forward. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23(10):552–562. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2012-046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allouche M, Boudriga N, Ahmed HB, Banasr A, Shimi M, Gloulou F, Zhioua M, Bouhajja B, Baccar H, Hamdoun M. Sudden death during sport activity in Tunisia: autopsy study in 32 cases. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2013;62(2):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron MS. My approach to clinical management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2014;24(7):314–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron BJ, Spirito P. Impact of patient selection biases on the perception of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and its natural history. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:970–972. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)91117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girolami F, Ho CY, Semsarian C, Baldi M, Will ML, Baldini K, Torricelli F, Yeates L, Cecchi F, Ackerman MJ, Olivotto I. Clinical features and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with triple sarcomere protein gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):1444–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]