Abstract

A PCR-based method for rapid detection of food-borne thermotolerant campylobacters was evaluated through a collaborative trial with 12 laboratories testing spiked carcass rinse samples. The method showed an interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity of 96.7% and a diagnostic specificity of 100% for chicken samples, while these values were 94.2 and 83.3%, respectively, for pig samples.

Meat products are among the primary sources of food-borne campylobacteriosis (24). Rapid detection of Campylobacter in these foodstuffs can improve food safety (21). To facilitate implementation of the PCR method by the food industry, it is recommended that the performance characteristics of the tests be thoroughly evaluated through collaborative trials (3).

Thus, a European research project, FOOD-PCR, for validation and standardization of noncommercial PCR-based methods as alternatives to traditional culture-based methods was launched (10).

None of the already published PCR-based methods for detection of thermotolerant Campylobacter (6, 7, 18, 19, 22) included an internal amplification control (IAC), nor has any been validated through interlaboratory collaborative trials, which are essential if the method is intended as a diagnostic tool in laboratories with quality assurance programs (3).

In the first stages of the project a sensitive and specific PCR assay for the detection of thermotolerant Campylobacter was developed (16) and validated through a multicenter collaborative trial testing purified DNA (17). The assay has been shown to detect all food-borne thermotolerant campylobacters (Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari), which will prepare laboratories for unforeseen shifts in prevalence from one species to the others (16).

To mediate the detection of campylobacters in materials used in primary food production, the PCR assay was incorporated in a complete method, in which the preceding steps were enrichment in Bolton broth followed by a simple and nonproprietary DNA extraction procedure (13). The present paper describes the performance of this method in complex matrices (enriched carcass rinse from chickens and pig swabs), as evaluated in a multicenter trial.

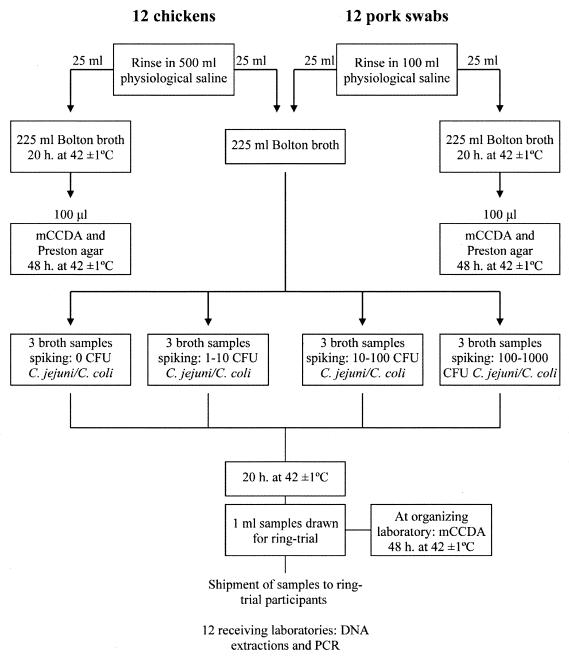

The collaborative trial was designed according to international recommendations (2). Twelve laboratories from the United Kingdom, Austria, Germany, Greece, Slovakia, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Italy, Sweden, The Netherlands, and Norway received 24 coded (blind) 1-ml enriched samples, 12 chicken samples and 12 pig samples, spiked with C. jejuni 1677 and C. coli 3931, respectively. The samples were spiked at the following levels: 0, 1 to 10, 10 to 100, and 100 to 1,000 CFU/250 ml (Fig. 1). Applying low, medium, and high levels of spiking makes it possible to assess the usefulness of the test at various infection levels. The shipment also included a positive DNA control, an IAC (16), bovine serum albumin (20 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and a resin used for the DNA extraction (Chelex-100; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram showing the preparation, spiking, testing, and shipping of samples for the PCR collaborative trial for detection of thermotolerant Campylobacter. The chicken samples were inoculated with C. jejuni; the pig samples were inoculated with C. coli.

A detailed standard operating procedure (SOP) explaining how to perform the pre-PCR treatment and the PCR assay (see www.pcr.dk for detailed information) was sent to the participating laboratories. The SOP required inclusion of a nontemplate control in every setup. The participants purchased their own primers, DNA polymerase (Tth; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and additional reagents from local suppliers. Briefly, the DNA extraction method included short, high-speed centrifugation of 1 ml of enriched broth, addition of Chelex to the pellet, incubation in a 56°C water bath, and final centrifugation (13). The SOP also included a reporting sheet, to be returned to the Central Science Laboratory, Sand Hutton, United Kingdom (not the sending laboratory), for statistical analysis. Participants were required to report in detail all additional information that could possibly have influenced their results.

Twelve frozen chickens, declared to be Campylobacter free by the producer (Danpo A/S, Aars, Denmark), were purchased at local retailers in Copenhagen, Denmark. Initial suspensions of chicken rinse were prepared as recommended in the ISO/CD 6887-2 protocol (1) and as described by Josefsen et al. (12). The pig carcass swabs, sampled in accordance with ISO/FDIS 17604 (9) by swabbing pig carcass areas of 1,400 cm2 with sterile gauze swabs, were obtained from the Danish Meat Research Institute (Roskilde, Denmark). Initial suspensions of 12 carcass swabs were prepared by washing the swabs in 100 ml of physiological saline for 60 s (13). As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 25 ml of chicken or pig swab rinse was transferred to 225 ml of blood-containing Bolton broth prepared according to the recommendations of the Bacteriological Analytical Manual Online (11). To verify that the chicken and pig swab rinses were initially culture negative, samples were drawn for intensive culturing before the inoculations. This analysis was conducted in accordance with recommendations of both ISO 10272-1 (4) and the Nordic Committee on Food Analysis (20), in order to verify the Campylobacter-free status of the samples.

C. jejuni 1677 and C. coli 3931 (which are frequently isolated from chickens and pigs, respectively) were inoculated into chicken and pig broth samples, respectively. Three broth samples were left noninoculated, three were inoculated with approximately 1 to 10 CFU/250 ml, three were inoculated with approximately 10 to 100 CFU/250 ml, and three were inoculated with approximately 100 to 1,000 CFU/250 ml. All samples were enriched for 20 h at 42 ± 1°C under microaerobic conditions. One-milliliter broth samples were drawn and stored at −80°C (maximum storage period: 3 weeks), until shipped on dry ice by courier to the participants. Prior to the shipment, identical samples were tested by PCR in the organizing laboratory (Danish Institute for Food and Veterinary Research, Copenhagen, Denmark) according to the SOP to verify the detection of thermotolerant Campylobacter.

The participating laboratories mailed the results directly to the Central Science Laboratory (a different laboratory than the organizing laboratory). The gel pictures were carefully examined, and the results were approved for inclusion in statistical analysis unless they fell into one of the following two categories: (i) obvious performance deviation from the SOP and (ii) presence of target amplicons in negative PCR controls, indicating contamination.

Table 1 shows the participants' results for the collaborative trial. In agreement with the predefined criteria, the results of partner 2 were excluded, as this partner did not include the IAC in the PCR mixture and thus was not able to determine whether the samples were truly negative or whether the absence of target amplicons was due to PCR inhibition. The results of partner 7 were also excluded, as partner 7 reported target amplicons in the assay negative control, indicating possible cross-contamination. All remaining results were accepted according to the predefined criteria; thus the final statistical analysis was based on 10 sets of results (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Reported participant results for the PCR-based method for detection of thermotolerant campylobacters in spiked chicken rinse and pig swab rinse samples

| Inoculation level | No. of samples positive for the target PCR amplicon

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expecteda | From chickens for participant:

|

From pigs for participant:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7c | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7c | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Noninoculated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Low (1-10 CFU) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Medium (10-100 CFU) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| High (100-1,000 CFU) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

From analysis of triplicate samples.

Excluded due to omission of the IAC in the PCR mixture.

Excluded due to the presence of target amplicons in the assay negative control.

TABLE 2.

Statistical evaluation of PCR results obtained for the detection of thermotolerant campylobacters in chicken rinse and pig swab rinse samplesa

| Inoculation level | Sensitivity (%)

|

Specificity (%)

|

Accordance (%)

|

Concordance (%)

|

COR

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | |

| Noninoculated | —b | — | 83.3 (66.4, 92.7) | 100 (88.7, 100) | 73.3 (53.3, 93.3) | 100 | 71.1 (55.8, 93.3) | 100 | 1.12 (0.73, 1.67) | 1.00 |

| Low | 100 (88.7, 100) | 93.3(78.7, 98.2) | — | — | 100 | 93.3 (80.0, 100) | 100 | 86.7 (65.9, 100) | 1.00 | 2.15 (1.00, 2.15) |

| Medium | 96.7 (83.3, 99.4) | 96.7 (83.3, 99.4) | — | — | 93.3 (80.0, 100) | 93.3 (80.0, 100) | 93.3 (81.5, 100) | 93.3 (81.5, 100) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.00) | 1.00 |

| High | 96.7 (83.3, 99.4) | 100 (88.7, 100) | — | — | 93.3 (80.0, 100) | 100 | 93.3 (81.5, 100) | 100 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.00) | 1.00 |

| All positive levels | 94.2 (88.5, 97.2) | 96.7 (90.7, 98.9) | — | — | 96.1 (88.3, 100) | 95.0 (85.0, 100) | 95.6 (87.3, 100) | 93.3 (81.5, 100) | 1.15 (1.00, 1.15) | 1.36 (1.00, 1.36) |

Numbers in parentheses are the lower and upper 95% CI values, respectively.

−, not applicable.

The PCR results were analyzed statistically according to the recommendations of Scotter et al. (23) by the method of Langton et al. (14). The interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity was defined as the percentage of positive samples giving a correct positive signal (8). The interlaboratory diagnostic specificity was defined as the percentage of negative samples giving a correct negative signal, as well as a signal from the IAC (8). Confidence intervals (CI) for interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were calculated by the method of Wilson (25). Accordance (repeatability of qualitative data) and concordance (reproducibility of qualitative data) were defined as the percentages of finding the same result, positive or negative, from two similar samples analyzed in, respectively, the same or different laboratories under standard repeatability conditions. These calculations take into account different replications in different laboratories by weighting results appropriately. The concordance odds ratio (COR) was defined as the degree of between-laboratory variation in the results. The COR was expressed as the ratio between accordance and concordance percentages. CI for accordance, concordance, and COR were calculated by the method of Davidson and Hinckley (5).

For chicken samples, the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity of the PCR was greater than 90% for each of the inoculation levels, and calculating the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity for all inoculation levels gave a value of 96.7% (Table 2). Accordance (repeatability) and concordance (reproducibility) values were thus high in each case. With samples inoculated with 1 to 10 CFU, a degree of interlaboratory variation was noted; this was due to one laboratory reporting two false-negative results. The COR value can be interpreted as the likelihood of obtaining the same result from two identical samples, whether they are sent to the same laboratory or to two different laboratories. The closer the value is to 1.0, the higher the likelihood is of obtaining the same result. In all cases, the COR value fell within the 95% CI, indicating that the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity of the method was as repeatable as it was reproducible (Table 2). Thus, the method is effective at detecting thermotolerant Campylobacter in the sample types tested. Conversely, and more importantly, there is a very low risk of obtaining false-negative responses: the interlaboratory diagnostic specificity, or percentage of correctly identified noninoculated chicken samples, was 100%, with complete accordance and concordance. The PCR-based method reported performed favorably compared to the International Standard Organisation culture method (13). The latter takes 5 days to identify negative samples, while the method reported here takes only two working days. Here it must be emphasized that the main advantage of PCR over culture methods is its potential for rapid screening of negative samples, which allows for greater resources to be directed toward characterization and epidemiological tracking of positive isolates. In end use laboratories using PCR for screening purposes, a confirmation of PCR-positive responses by culture may not be necessary.

A similar approach has been used in Denmark for identification of infected flocks prior to and after slaughter, in order to provide the consumers with campylobacter-free chickens, declared as such. The implementation of the so-called “strategic slaughter,” where infected flocks are slaughtered at the end of the day, seems to have contributed to the recent significant decline of human campylobacteriosis in Denmark (www.dzc.dk).

For the pig samples, the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity of the PCR was greater than 90% for each inoculation level and calculating the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity for all inoculation levels resulted in a value of 94.2% (Table 2). In all cases accordance and concordance values were high, and the CORs showed that the interlaboratory diagnostic sensitivity was equally repeatable and reproducible. For these samples, the interlaboratory diagnostic specificity was 83.3%, reflecting a greater degree of interlaboratory variation in results for pig samples. This was due to four laboratories reporting positive amplicons from noninoculated samples. Since the pig samples had previously been identified as Campylobacter free, both by culture and PCR in the sending laboratory, cross-contamination in the receiving laboratories could explain these results. With hindsight, this could have been controlled within the trial by including a processing negative control (PNC), e.g., a sample comprising sterile water, which underwent treatment identical to that of the samples. A positive result from a PNC sample would reveal the occurrence of cross-contamination. This is a drawback of the present study, which should be avoided in similar trials in the future. In addition, if the method is to be performed routinely, it is strongly recommended that such controls be included throughout the entire test process, including sample preparation, enrichment, DNA extraction, and target amplification (3). However, in routine application of the PCR method, any positive response should be confirmed by reanalyzing the retained Bolton broth culture by the ISO method.

To our best knowledge, no other collaborative trial has validated a similar noncommercial, open-formula PCR for Campylobacter (15). The method does not require procurement of costly equipment. These features, in combination with the validation presented here, make it suitable for routine use and thus appropriate for accreditation.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by EC grants QLK1-CT-1999-00226 and 3401-66-03-5 from the Directorate for Food, Fisheries and Agricultural Business.

The following contributed with their participation in the collaborative trial: M. Wagner, K. Demnerova, A. E. Heuvelink, V. Kmet, P. Fach, H. Lindmark, P. T. Tassios, S. Loncarevic, M. Barbanera, M. Kuhn, and A. Abdulmawjood. We acknowledge the technical assistance of all the laboratory staff involved in preparing and analyzing the samples used in the collaborative trial. Danpo provided the chicken samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 2000. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs. Preparation of test samples, initial suspension and decimal dilution for microbiological examination. Part 2. Specific rules for the preparation of the initial suspension and decimal dilutions of meat and meat products. International Standard Organisation ISO/CD 6887-2. ISO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2.Anonymous. 2001. NordVal validation. Protocol for the validation of alternative microbiological qualitative methods. NV-DOC. D-2001-04-25. FDIR, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 3.Anonymous. 2002. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the detection of foodborne pathogens. General method specific requirements. Draft international standard ISO/DIS 22174. DIN, Berlin, Germany.

- 4.Anonymous. 2002. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs. Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Campylobacter growing at 41.5°C. Part 1. Detection method. International Standard Organisation ISO/TC 34/SC 9 N 553, revision 2. Result of voting on ISO/CD 10272-1. AFNOR, Paris, France.

- 5.Davidson, A. C., and D. V. Hinckley. 1997. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 6.Denis, M., J. Refrégier-Petton, M. J. Laisney, G. Ermel, and G. Salvat. 2001. Campylobacter contamination in French chicken production from farm to consumers. Use of a PCR assay for detection and identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Camp. coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:255-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englen, M. D., and L. C. Kelley. 2000. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for the identification of Campylobacter jejuni by the polymerase chain reaction. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31:421-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Committee for Standardization. 2002. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs. Protocol for the validation of alternative methods (ISO/FIDS 16140). AFNOR, Paris, France.

- 9. European Committee for Standardization. 2003. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs. Carcass sampling for microbiological analysis (ISO/FIDS 17604). AFNOR, Paris, France.

- 10.Hoorfar, J. 1999. EU seeking to validate and standardize PCR testing of food pathogens. ASM News 65:799. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt, J. M., C. Abeyta, and T. Tran. 1998. Campylobacter. In G. J. Jackson, R. I. Merker, and R. Bandler (ed.), Bacteriological analytical manual online, 8th ed., revision A. [Online.] www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼ebam/bam-toc.html.

- 12.Josefsen, M. H., P. S. Lübeck, B. Aalbäk, and J. Hoorfar. 2002. Preston and Park-Sanders protocols adapted for semi-quantitative isolation of thermotolerant Campylobacter from chicken rinse. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 80:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Josefsen, M. H., P. S. Lübeck, F. Hansen, and J. Hoorfar. 2004. Towards an international standard for PCR-based detection of foodborne thermotolerant campylobacters: interaction of enrichment media and pre-PCR treatment on carcass rinse samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 58:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langton, S. D., R. Chevennement, N. Nagelkerke, and B. Lombard. 2002. Analysing collaborative trials for qualitative microbiological methods: accordance and concordance. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 79:175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lübeck, P. S., and J. Hoorfar. 2002. PCR technology and applications to zoonotic foodborne bacterial pathogens. Methods Mol. Biol. 216:65-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lübeck, P. S., P. Wolffs, S. L. On, P. Ahrens, P. Radstrom, and J. Hoorfar. 2003. Toward an international standard for PCR-based detection of food-borne thermotolerant campylobacters: assay development and analytical validation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5664-5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lübeck, P. S., N. Cook, M. Wagner, P. Fach, and J. Hoorfar. 2003. Toward an international standard for PCR-based detection of food-borne thermotolerant campylobacters: validation in a multicenter collaborative trial. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5670-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magistrado, P. A., M. M. Garcia, and A. K. Raymundo. 2001. Isolation and polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from poultry in the Philippines. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno, Y., M. Harnández, M. A. Ferrús, J. L. Alonso, S. Botella, R. Montes, and J. Hernández. 2001. Direct detection of thermotolerant campylobacters in chicken products by PCR and in situ hybridisation. Res. Microbiol. 152:577-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordic Committee on Food Analysis. 2002. Campylobacter. Detection and enumeration of thermotolerant Campylobacter in foods. Draft version. Nordic Committee on Food Analysis, Oslo, Norway.

- 21.On. S. L. W. 1996. Identification methods for campylobacters, helicobacters, and related organisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:405-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Sullivan, N. A., R. Fallon, C. Carroll, T. Smith, and M. Maher. 2000. Detection and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in broiler chicken samples using a PCR/DNA probe membrane based colorimetric detection assay. Mol. Cell Probes 14:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scotter, S. L., S. Langton, B. Lombard, N. Schulten, N. Nagelkerke, P. H. In't Veld, P. Rollier, and C. Lahellec. 2001. Validation of ISO method 11290. Part 1. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes in foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 64:295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tauxe, R. V. 2002. Emerging foodborne pathogens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78:31-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson, E. B. 1927. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J. Am. Statis. Assoc. 22:209-212. [Google Scholar]