Abstract

Background

People with active tuberculosis (TB) require six months of treatment. Some people find it difficult to complete treatment, and there are several approaches to help ensure completion. One such system relies on reminders, where the health system prompts patients to attend for appointments on time, or re‐engages people who have missed or defaulted on a scheduled appointment.

Objectives

To assess the effects of reminder systems on improving attendance at TB diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment clinic appointments, and their effects on TB treatment outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, CINAHL, SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, mRCT, and the Indian Journal of Tuberculosis without language restriction up to 29 August 2014. We also checked reference lists and contacted researchers working in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster RCTs and quasi‐RCTs, and controlled before‐and‐after studies comparing reminder systems with no reminders or an alternative reminder system for people with scheduled appointments for TB diagnosis, prophylaxis, or treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias in the included trials. We compared the effects of interventions by using risk ratios (RR) and presented RRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Also we assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Nine trials, including 4654 participants, met our inclusion criteria. Five trials evaluated appointment reminders for people on treatment for active TB, two for people on prophylaxis for latent TB, and four for people undergoing TB screening using skin tests. We classified the interventions into 'pre‐appointment' reminders (telephone calls or letters prior to a scheduled appointment) or 'default' reminders (telephone calls, letters, or home visits to people who had missed an appointment).

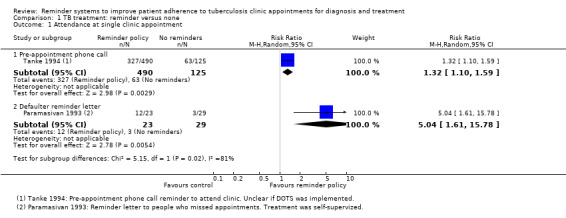

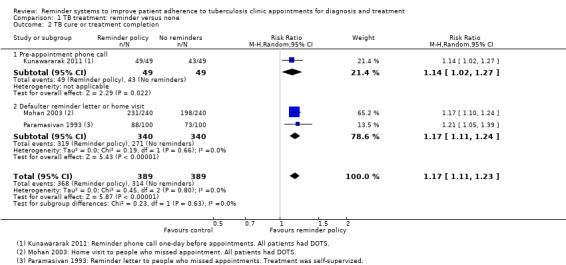

For people being treated for active TB, clinic attendance and TB treatment completion were higher in people receiving pre‐appointment reminder phone‐calls (clinic attendance: 66% versus 50%; RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.59, one trial (USA), 615 participants, low quality evidence; TB treatment completion: 100% versus 88%; RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.27, one trial (Thailand), 92 participants, low quality evidence). Clinic attendance and TB treatment completion were also higher with default reminders (letters or home visits) (clinic attendance: 52% versus 10%; RR 5.04, 95% CI 1.61 to 15.78, one trial (India), 52 participants, low quality evidence; treatment completion: RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.24, two trials (Iraq and India), 680 participants, moderate quality evidence).

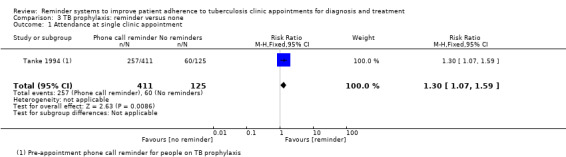

For people on TB prophylaxis, clinic attendance was higher with a policy of pre‐appointment phone‐calls (63% versus 48%; RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.59, one trial (USA), 536 participants); and attendance at the final clinic was higher with regular three‐monthly phone‐calls or nurse visits (93% versus 65%, one trial (Spain), 318 participants).

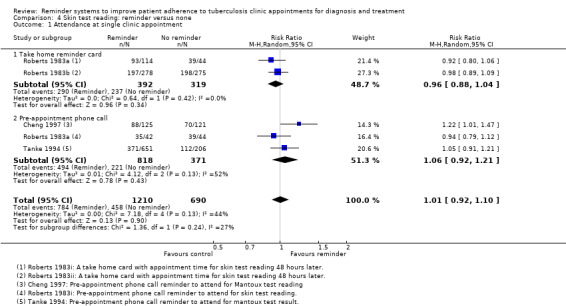

For people undergoing screening for TB, three trials of pre‐appointment phone‐calls found little or no effect on the proportion of people returning to clinic for the result of their skin test (three trials, 1189 participants, low quality evidence), and two trials found little or no effect with take home reminder cards (two trials, 711 participants). All four trials were conducted among healthy volunteers in the USA.

Authors' conclusions

Policies of sending reminders to people pre‐appointment, and contacting people who miss appointments, seem sensible additions to any TB programme, and the limited evidence available suggests they have small but potentially important benefits. Future studies of modern technologies such as short message service (SMS) reminders would be useful, particularly in low‐resource settings.

15 April 2019

Update pending

Studies awaiting assessment

The CIDG is currently examining a search conducted up to 18 Jul, 2018 for potentially relevant studies. These studies have not yet been incorporated into this Cochrane Review.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Humans; Appointments and Schedules; Reminder Systems; Directly Observed Therapy; Latent Tuberculosis; Latent Tuberculosis/prevention & control; Patient Compliance; Patient Compliance/statistics & numerical data; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Skin Tests; Skin Tests/statistics & numerical data; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/diagnosis; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Reminder systems to improve patient attendance at tuberculosis clinics

This Cochrane Review summarizes trials evaluating the effects of reminder systems on attendance at tuberculosis (TB) clinics and completion of TB treatment. After searching for relevant trials up to 29 August 2014, we included nine trials, including 4654 people.

What are reminder systems and how might they help?

Effective treatment for TB requires people to take multiple drugs daily for at least six months. Consequently, once they start to feel well again, some patients stop attending clinics and stop taking their medication which can lead to the illness returning and the development of drug resistance. One strategy the World Health Organization recommends is that an appointed person (a health worker or volunteer) watches the person take their medication everyday (called direct observation). Other strategies include reminder systems to prompt patients to attend for appointments on time, or to re‐engage people who have missed or defaulted on a scheduled appointment. These prompts may be in the form of telephone calls or letters before the next scheduled appointment ("pre‐appointment reminders"), or phone calls, letters, or home visits after a missed appointment ("default reminders").

What the research says:

For people being treated for active TB:

‐ More people attended the clinic and completed TB treatment with pre‐appointment reminder phone‐calls (low quality evidence).

‐ More people attended the clinic and completed TB treatment with a policy of default reminders (low and moderate quality evidence respectively).

For people on TB prophylaxis:

‐ More people attended the clinic with pre‐appointment phone‐calls, and the number attending the final clinic was higher with three‐monthly phone‐calls or nurse home visits.

For people undergoing screening for TB:

‐ Similar numbers of people attended clinic for skin test reading with and without pre‐appointment phone‐calls (low quality evidence).

‐ Similar numbers of people attended clinic for skin test reading with and without take home reminder cards.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings table 1.

| TB treatment: pre‐appointment reminder versus no reminder | |||||

| Patient or population: People on TB treatment Settings: Outpatient clinic Intervention: Pre‐appointment reminder Comparison: No reminder | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| No reminder | Pre‐appointment reminder | ||||

| Attendance at single clinic appointment | 50 per 100 |

66 per 100 (55 to 80) |

RR 1.32 (1.10 to 1.59) |

615 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Completion of TB treatment | 88 per 100 |

100 per 100 (90 to 100) |

RR 1.14 (1.02 to 1.27) |

92 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5 |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: This trial was quasi‐randomized and is at high risk of selection bias. 2Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: Clinic attendance in this single trial from the USA is very low. It is unclear whether DOTS was implemented at the trial site, and the findings may not be easily generalizable elsewhere 3Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: No details of randomization are provided and the risk of selection bias. 4Downgraded by 1 for serious imprecision: This trial is very underpowered to detect this effect. 5No serious indirectness: This is a single trial of pre‐appointment phone call reminders in adults from Thailand where DOTS was being implemented. Although its findings may not be easily generalized to all settings, it is likely to be similar to TB‐endemic settings in developing countries.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table 2.

| TB treatment: defaulter reminder versus no reminder | |||||

| Patient or population: People on TB treatment Settings: Outpatient clinic Intervention: Default reminder Comparison: No reminder | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| No reminder | Defaulter reminder | ||||

| Attendance at single clinic appointment | 10 per 100 |

52 per 100 (17 to 100) |

RR 5.04 (1.61 to 15.78) | 52 (1 trial) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 |

| Completion of TB treatment | 78 per 100 | 91 per 100 (87 to 97) | RR 1.17 (1.11 to 1.24) | 680 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7 |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1No serious risk of bias: This trial was at low risk of selection bias, but was unblinded. 2Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: This outcome was only reported from a single trial setting in India where DOTS was not implemented and attendance at clinic was very low. The result may not be easily generalizable elsewhere. 3Downgraded by 1 for serious imprecision: This trial was underpowered to confidently detect clinically important effects. 4No serious risk of bias: Both trials were at low risk of selection bias. 5No serious inconsistency: This finding was consistent across trials. 6Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: The two trials were conducted in Iraq and India and DOTS was only implemented in the Iraq trial. One trial used home visits and one used reminder letters. The findings may not be easily generalized to all settings, and interventions may need adapting to the local context. 7No serious imprecision: The trials are adequately powered to detect this effect.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table 3.

| TB skin testing: pre‐appointment reminder versus no reminder | |||||

| Patient or population: People at risk of TB Settings: Outpatient clinic Intervention: Pre‐appointment reminder Comparison: No reminder | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| No reminder | Pre‐appointment reminder | ||||

| Attendance at clinic | 60 per 100 | 63 per 100 (55 to 72) | RR 1.06 (0.92 to 1.21) | 1189 (3 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: Two trials are quasi‐RCTs and at high risk of selection bias. The third provides few details of randomization and is at unclear risk. 2Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: All three trials were conducted in the USA between 1983 and 1997, and the results may not be easily generalized to elsewhere.

Background

Description of the condition

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and spreads from person to person through inhalation of droplets nuclei. As a cause of human suffering, death, and impoverishment, TB ranks among the leading infectious diseases. In 2012, there were an estimated 8.6 million incident cases of TB and 1.3 million TB‐related deaths worldwide (WHO 2013).

In some settings, groups of people considered to be at high risk may be screened for latent TB infection using Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) tests (also known as tuberculin skin tests), such as the Mantoux or Heaf tests, or the more recently developed interferon‐gamma blood tests. PPD tests involve injecting a protein derivative of the M. tuberculosis bacillus into the skin, waiting 48 to 72 hours, and then measuring any localized swelling (or induration) of the skin around the injection site. People with positive results may then undergo further tests to detect or exclude active TB. Latent TB is treated for up to 12 months with antituberculous drugs to clear the latent infection and prevent the development of active disease; termed 'TB prophylaxis'.

The standard method for diagnosing active pulmonary TB (PTB) is sputum microscopy and culture, where people provide two or three sputum samples, including an early morning sample, collected on separate occasions. Patients are advised to return to the clinic to receive the results, and those with positive results are then referred for treatment. More recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has also recommended the use of a rapid molecular diagnostic test, known as Xpert® MTB/RIF, which can provide results within two hours (WHO 2011;Steingart 2014).

Treatment for active TB requires patients to take multiple medications for at least six months. The standard regimen currently recommended by the WHO includes four drugs for two months (the intensive phase), followed by two drugs for four months (the consolidation phase) (WHO 2003a).

Poor adherence to antituberculous treatment may lead to treatment failure and relapse (Ormerod 1991), drug resistance (Weis 1994; Mitchison 1998), and prolonged and expensive therapy that is less likely to be successful than the treatment of drug‐susceptible TB (Goble 1993). Poor adherence also results in increased transmission rates of the tubercle bacilli, morbidity, and cost to the TB control programmes (Johansson 1999).

Description of the intervention

Adherence to a TB diagnosis and treatment programme requires accessible and appropriate health care, and a number of interventions have been used to promote adherence (WHO 2003b). Directly observed therapy (DOT), where an appointed agent (health worker, community volunteer, or family member) watches the patient swallow their medication each day, has been the mainstay of adherence promotion since its introduction in the 1990s, and the randomized evidence of its effects is summarized in a previous systematic review (Volmink 2007).

Reminder systems are policies implemented by the health service to improve or maintain attendance at appointments or adherence to treatment. The reminders may consist of home visits to patients, letters, telephone calls, e‐mails or short message service (SMS) text messages (Thilakavathi 1993; Green 2003), and may be undertaken by health service staff, volunteers, or community members. They may sometimes include a health education component; explaining to the patient the benefits of attending appointments and taking medication. In this review we classify the reminder systems into:

Pre‐appointment reminders; defined as any action to contact patients shortly before they are due to take their medication or attend a healthcare appointment, and remind them to take their medication or attend their appointment, and

Default reminders (sometimes called 'defaulter actions' or 'late patient tracers'); defined as actions undertaken when a patient fails to keep an appointment. They generally aim to re‐establish contact with the patient, to find out why they did not attend, and to encourage re‐engagement with services.

This Cochrane Review is one of several published, planned, or in progress to evaluate different strategies to promote adherence:

Reminder systems to improve patient adherence to TB clinic appointments for diagnosis and treatment: reminding patients to keep an appointment and actions taken when patients fail to keep an appointment (this review).

DOT: an appointed agent (health worker, community volunteer, family member) directly monitors people swallowing their antituberculous drugs (Volmink 2007). (This is one of the five components of the wider strategy called 'DOTS' (the directly observed treatment, short course), which remains at the heart of global Stop TB Strategy (WHO 2006)).

Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for TB: provision of information or one‐to‐one or group counselling about TB and the need to complete treatment (M'Imunya 2012).

Material incentives and enablers in the management of TB: cash or vouchers for patients to promote their return for the results of tests or to take prescribed treatments (Lutge 2012).

Staff motivation and supervision: training and management processes that aim to improve how providers care for people with TB.

Peer assistance: people from the same social group helping someone with TB return to the health service by prompting or accompanying them.

How the intervention might work

Reminders are not newly developed interventions, and some national treatment programmes use one or both types of reminders as standard procedure. For example, in South Africa, the TB control programme uses a client‐held card and a clinic card where the next appointment is recorded, which serve as a pre‐appointment reminder to both the patients and the health workers (National Department of Health South Africa 2014). In 1988 to 1989, the national treatment programme manuals in India recommended defaulter reminders to contact patients who did not return to the clinic for their fortnightly drug collection, on the first day after a missed appointment and then on the fourth day (Jagota 1996). In Malaysia, where DOT is used, when patients have missed more than seven consecutive days of treatment, a specialist tracing team visits their home to find out why they have not attended the clinic for treatment. Another visit is made if the patient subsequently fails to attend (O'Boyle 2002).

Due to increasing MDR‐TB prevalence in many countries, actions to remind patients about attending clinic appointments for diagnosis and treatment play an important role in preventing multi‐drug resistance to anti‐TB drugs. In this review, we look at the effects of reminders in two aspects: (1) whether a single reminder action has any potential efficacy on attendance at the next TB clinic appointment; and (2) whether a policy of regularly reminding patients who missed their appointments could improve their outcomes including TB cure or treatment completion.

Why it is important to do this review

Reminder systems as strategies to improve patients' adherence to TB screening, diagnosis, and treatment have not been reviewed systematically before. This Cochrane Review seeks to fill the gap in evidence, and highlight where more research might be needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of reminder systems on improving attendance at TB diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment clinic appointments, and their effects on TB treatment outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including cluster RCTs and quasi‐RCTs.

Controlled before‐and‐after studies (CBAs).

Types of participants

Children and adults in any setting who require treatment for TB. This includes people with PTB (diagnosed by sputum microscopy, culture, or both, regardless of HIV status), smear‐negative PTB (diagnosed by symptoms and chest radiograph findings, or other diagnostic tests, regardless of HIV status), or extrapulmonary TB (diagnosed by signs or symptoms and histopathology, sputum acid‐fast bacilli smear, culture, or both, imaging studies or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)).

Children and adults in any setting with TB infection who require prophylaxis against TB.

Children and adults in any setting referred (including self‐referred) to TB diagnostic or screening services.

Types of interventions

Interventions

Any actions taken to remind patients to take their TB medication or attend appointments (pre‐appointment reminders).

Any actions to contact patients who have missed an appointment (default reminders).

Controls

No reminders.

Other kinds of reminder actions or other interventions to improve adherence.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Completion of TB diagnostics.

Completion of screening process.

Commencement of prophylactic treatment.

Commencement of curative treatment.

Completion of prophylactic treatment.

Completion of curative treatment.

Cure.

Incidence of active TB (in studies of prophylactic treatment).

Secondary outcomes

Any measure of adherence to treatment or attendance at appointments.

Any measure of patient involvement or patient satisfaction.

Any adverse event (for example, elevated liver enzymes, optic neuritis).

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

Databases

We searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy described in Table 4: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (29 August 2014); Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group Specialized Register (29 August 2014); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library (2014, Issue 8); MEDLINE (1966 to 29 August 2014); EMBASE (1974 to 29 August 2014); LILACS (1982 to 29 August 2014); CINAHL (1982 to 29 August 2014); Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED; 1945 to 29 August 2014); and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI; 1956 to 29 August 2014). We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) using the terms: 'tuberculosis' and '(reminder OR compliance)' (29 August 2014).

1. Detailed search strategies.

| Search set | Cochrane SRa | CENTRAL | MEDLINEb | EMBASEb | LILACSb | SCI‐EXPANDED & SSCI | CINAHL | |

| 1 | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | |

| 2 | adherence | PATIENT COMPLIANCE | TUBERCULOSIS/DRUG THERAPY/PREVENTION AND CONTROL | TUBERCULOSIS | adherence | adherence | adherence | |

| 3 | compliance | PATIENT DROPOUTS | PATIENT COMPLIANCE | PATIENT‐COMPLIANCE | compliance | compliance | compliance | |

| 4 | monitor* | REMINDER SYSTEMS | PATIENT DROPOUTS | medication adherence | Monitor$ | monitor* | monitor* | |

| 5 | reminder* | TREATMENT REFUSAL | COOPERATIVE BEHAVIOUR | REMINDER‐SYSTEM | Reminder$ | reminder* | reminder* | |

| 6 | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | DIRECTLY OBSERVED THERAPY | TREATMENT REFUSAL | TREATMENT‐REFUSAL | phone or SMS$ or text or messaging | non‐adherence | non‐adherence | |

| 7 | 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | medication adherence | medication adherence | DIRECTLY‐OBSERVED‐THERAPY | 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | late patient tracer | late patient tracer | |

| 8 | 1 and 7 | electronic monitoring | REMINDER SYSTEMS | electronic monitoring | 1 and 7 | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | |

| 9 | — | nonadherence | electronic monitoring | nonadherence | — | 2‐8/OR | 2‐8/OR | |

| 10 | — | non‐adherence | nonadherence | non‐adherence | — | 1 AND 9 | 1 AND 9 | |

| 11 | — | late patient tracer | non‐adherence | late patient tracer | — | — | — | |

| 12 | — | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | DIRECTLY OBSERVED THERAPY | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | — | — | — | |

| 13 | — | 2‐12 | late patient tracer | 1 or 2 | — | — | — | |

| 14 | — | 1 AND 13 | phone or SMS* or text or messaging | 3‐12/OR | — | — | — | |

| 15 | — | — | 1 or 2 | 13 and 14 | — | — | — | |

| 16 | — | — | 3‐14/OR | — | — | — | — | |

| 17 | — | — | 15 and 16 | — | — | — | — | |

aCochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Specialized Register. bSearch terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Lefebvre 2011). For controlled "before and after" studies, we used the terms: "before and after"; time series analysis; cohort analysis; controlled study. Upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term.

Researchers and organizations

For unpublished and ongoing trials, we contacted study authors and other researchers working in the field and the following organizations: WHO; the Tuberculosis Trials Consortium (TBTC); the International Union against TB and Lung Diseases (IUATLD); the European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Programme (EDCTP); and the Global Partnership to Stop TB.

Non‐indexed journals

We searched the online Indian Journal of Tuberculosis from 1983 to 29 August 2014 using 'tuberculosis' and '(reminder OR compliance)' as search terms.

Reference lists

We also checked the reference lists of all studies identified by the above methods.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

KA and MAL independently applied the inclusion criteria to all identified trials, and screened all citations and abstracts identified by the search strategy to exclude trials that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. If either review author judged that the trial might be eligible for inclusion, we obtained the full paper. After obtaining full reports of all potentially eligible studies, KA and QL assessed these for inclusion in the review using a pre‐designed eligibility form based on the inclusion criteria and resolved any disagreements by discussion with a third author (MAL). We also scrutinized publications to ensure that each trial was included only once. We excluded studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and documented the reasons for exclusion in the table of 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Data extraction and management

MA and VB independently extracted the data using a tailored data extraction form. We extracted data on trial design, methods, participant characteristics, interventions, and outcomes. For dichotomous data, we extracted the number of events of interest, the total number randomized to each group, and the total number analysed. For continuous data, we extracted the number of participants randomized, the number analysed, and the number of participants in each group; and also the arithmetic means and their standard deviations for some variables. We contacted trial authors to obtain missing information and to clarify issues. We resolved discrepancies by discussion with a third author (QL).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

MA and VB independently assessed the risk of bias in each included trial using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias (Higgins 2011). For RCTs and quasi‐RCTs, we assessed the random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and 'other bias'. For each included trial, the two review authors independently described the procedures that the trial authors reported for each domain and then made a decision relating to the risk of bias for that domain by assigning a judgement of 'low risk' of bias, 'high risk' of bias, or 'unclear risk' of bias. We also contacted the trial authors when essential information to judge quality was missing. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and by consulting a third review author (QL) when necessary.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous data.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include any cluster‐RCTs in our review, so the intracluster correlation coefficients (ICC) estimates were inappropriate.

Dealing with missing data

In order to appropriately describe the trial results, we contacted the trial authors to request missing data. We presented the results of the trials individually using an available‐case analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for heterogeneity using the Chi2 test for heterogeneity with a cut‐off of P < 0.10 and the I2 statistic, with > 50% indicating statistical significant heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Statistical assessment of potential publication bias was not possible given the small number of eligible trials.

Data synthesis

QL undertook the analyses using Review Manager 5 in consultation with the other review authors. All trials reported only dichotomous data, so we have expressed trial results as risk ratio (RR) with its 95% CIs for each outcome. When significant statistical heterogeneity was present and it was appropriate to combine the data, we used the random‐effects model. We stratified the analysis by the type of reminder (pre‐appointment reminders, default reminders), and trial design. For future updates, we will use the methods outlined in the protocol to handle other types of data that may become available (for example, continuous data, or analysis of cluster trials, or controlled before‐and‐after studies).

We used the GRADE approach to assess and grade the quality of evidence of primary outcomes. The quality rating across studies has four levels: high, moderate, low, or very low. RCTs are initially categorized as high quality but can be downgraded after assessment of five criteria: risk of bias, consistency, directness, imprecision, and publication bias (Guyatt 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to perform subgroup analysis, with subgroups defined by the participant age (adults or children), sex, setting (for example, rural or urban, high‐ or low‐income country), special populations (people with HIV/AIDS, intravenous drug users, refugees, asylum seekers, homeless people, and alcoholics), type of reminder (for example, letters, telephone calls, home visits, type of person contacting the patient), prophylactic or curative treatment, new cases or those who have previously interrupted treatment, method of diagnosis used, and type of treatment programme (for example, DOT, or mainly self‐administered). However, due to the small number of trials included in the review, we could not investigate heterogeneity using subgroups as previously planned.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding trials with high risk of bias to investigate the robustness of the results to the various risk of bias components.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies; and Table 5.

2. Summary of populations and interventions.

| Trial ID | Country | Age group | TB status | TB intervention | Supervision of treatment | Type of reminder | Timing of reminder | Pre/post appointment | Control |

| Roberts 1983b | USA | Adults | At risk of TB | Test | N/A | Take home reminder card1 | N/A | N/A | Verbal statement in clinic |

| Roberts 1983a | USA | Adults | At risk of TB | Test | N/A | Take home reminder card2 | N/A | N/A | Verbal statement in clinic |

| N/A | Postcard | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | Verbal statement in clinic | |||||

| N/A | Phone call | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | Verbal statement in clinic | |||||

| Tanke 1994 | USA | All | At risk of TB | Test | N/A | Phone call3 | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | No phone call |

| Cheng 1997 | USA | Children | At risk of TB | Test | N/A | Phone call | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | Take home reminder card |

| Salleras Sanmarti 1993 | Spain | Children | Asymptomatic | Prophylaxis | Parents | A routine phone call every 3 months | N/A | N/A | One‐off advice to take treatment for 12 months |

| A routine nurse home visit every 3 months | N/A | N/A | One‐off advice to take treatment for 12 months | ||||||

| A routine doctor clinic appointment every 3 months | N/A | N/A | One‐off advice to take treatment for 12 months | ||||||

| Tanke 1994 | USA | All | Asymptomatic | Prophylaxis | Unclear | Phone call3 | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | No phone call |

| Tanke 1994 | USA | All | Symptomatic | Treatment | Unclear | Phone call3 | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | No phone call |

| Kunawararak 2011 | Thailand | > 15 years | Symptomatic | Treatment | DOTS | Phone call | 1 day | Pre‐appointment | DOTS alone |

| Mohan 2003 | Iraq | Not stated | Symptomatic | Treatment | DOTS | Home visit | 3 days | Post‐appointment | DOTS alone |

| Krishnaswami 1981 | India | > 12 years | Symptomatic | Treatment | Self‐monthly pick‐up of meds | Home visit | 4 days | Post‐appointment | Reminder letter |

| Paramasivan 1993 | India | Adult | Symptomatic | Treatment | Self‐monthly pick‐up of meds | Reminder card | 3 days | Post‐appointment | No reminder card |

1Roberts 1983b also evaluated the effects of three types of participant commitment to return (no commitment, verbal, verbal plus written), and two types of verbal messaging on the importance of returning (enhanced versus standard). 2Roberts 1983aalso evaluated the effect of two types of verbal messaging on the importance of returning (expert versus non‐expert). 3Tanke 1994 evaluated four different automated phone messages: basic message, message with authority, message with importance, and message with authority and importance. No differences were seen between the different messages.

Results of the search

Figure 1 shows the summary of the trial selection process.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We obtained 1012 titles and abstracts after removal of duplicates from the electronic search of databases, and no additional articles from contacting researchers or screening reference lists. We judged 41 articles as potentially eligible after abstract screening and assessed the full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion. Seven studies are currently ongoing (CTRI/2011/07/001889; ISRCTN46846388; NCT01471977; NCT01549457; NCT01690754; NCT02082340; PACTR201307000583416).

Included studies

Nine trials involving 4654 participants met our inclusion criteria, of which two were reported in a single publication (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b).

Type of intervention

Pre‐appointment reminders

Two individually quasi‐RCTs (Tanke 1994; Cheng 1997) and four individually RCTs (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b; Salleras Sanmarti 1993; Kunawararak 2011) evaluated pre‐appointment reminders.

Roberts 1983a compared eight groups receiving four types of return reminders, including postcard, telephone call, direct person‐to‐person, and take‐home card in combination with two types of authority sources (experts and non‐experts). Roberts 1983b compared 12 groups receiving a combination of two types of message on the importance of returning (enhanced versus standard), two types of reminders (take‐home card versus no reminder card), and three types of overt commitment to return (verbal, verbal plus written agreement, or no commitment).

Except for one trial (Kunawararak 2011), all the other trials had more than one intervention arm. Kunawararak 2011 compared DOTS plus a daily mobile phone call reminder with DOTS only. Cheng 1997 applied five types of intervention for following up the TB test reading, of which the intervention of interest for this review was the reminder phone call in group 2. Tanke 1994 compared no message with four types of automated telephone reminders (basic reminder, basic reminder plus authority endorsement, basic reminder plus importance statement, and basic reminder plus importance statement plus authority endorsement) for patients scheduled for three different clinic appointments. Salleras Sanmarti 1993 compared three types of intervention with a control; the interventions in groups one and two (telephone call reminder and home visit by specialized nursing personnel) met our inclusion criteria.

Default reminders

Three individually RCTs met our inclusion criteria (Krishnaswami 1981; Paramasivan 1993; Mohan 2003). Krishnaswami 1981 compared the effectiveness of two kinds of default reminders, a home visit and if necessary up to another three visits compared with a reminder letter the first time and if necessary a home visit once. Paramasivan 1993 and Mohan 2003 compared reminder letters or routine home visiting for patients missing an appointment with a control group without reminders. In Mohan 2003, the home visitors also carried out health education for the patient and his/her family.

Countries

Most of the trials assessing pre‐appointment reminders were carried out in the USA (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b; Tanke 1994; Cheng 1997), except one trial carried out in Spain (Salleras Sanmarti 1993) and one in Thailand (Kunawararak 2011). Of the trials assessing default reminders, two were carried out in India (Krishnaswami 1981; Paramasivan 1993) and one in Iraq (Mohan 2003).

Participants

For pre‐appointment reminders:

One was conducted in new sputum smear positive PTB patients including both non‐MDR‐TB and MDR‐TB (Kunawararak 2011).

One was conducted in primary school children undergoing TB chemoprophylaxis (Salleras Sanmarti 1993).

Three trials assessed the effectiveness of different reminders on the tuberculin skin test return in different trial populations: Cheng 1997 studied children aged 1 to 12 years; and Roberts 1983a/Roberts 1983b studied college students who were volunteers in a university‐sponsored TB detection drive.

One was conducted in a wide range of age groups receiving TB diagnosis, TB chemoprophylaxis, or treatment (Tanke 1994).

For default reminders, all three trials were conducted among patients undergoing treatment for active TB:

Krishnaswami 1981 included patients aged 12 years or more with radiographic evidence of TB but negative smears.

Paramasivan 1993 studied newly diagnosed adult sputum smear‐positive PTB patients.

Mohan 2003 studied new smear‐positive PTB patients who delayed coming to collect drugs at the health centre for at least three days after a scheduled appointment.

Setting

The six pre‐appointment reminder trials were performed in different settings, including a children's national medical centre (Cheng 1997), clinics (Tanke 1994), a public hospital (Kunawararak 2011), a primary school (Salleras Sanmarti 1993), and a university (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b). All three default reminder trials were performed in clinics (Krishnaswami 1981; Paramasivan 1993; Mohan 2003).

Outcomes

The main outcomes assessed in the pre‐appointment reminder trials were the number of patients who adhered to a scheduled appointment and cure, defined in the protocol; and for default reminders, the number of patients who completed treatment.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐six studies that initially seemed to fit the inclusion criteria were eventually excluded for the reasons given in the table of Characteristics of excluded studies. The most common reasons for exclusion were no intervention of interest included and inappropriate study design (such as, non‐randomized clinical trials).

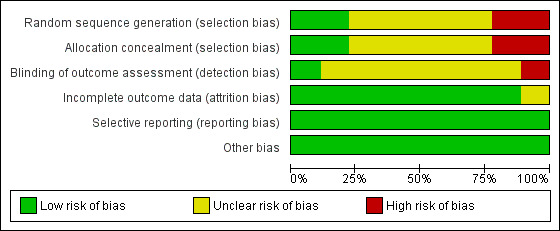

Risk of bias in included studies

Our assessment of risk of bias is summarized in the Characteristics of included studies table, Figure 2, and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial.

Allocation

For pre‐appointment reminder trials, two trials used a quasi‐RCT design (Tanke 1994; Cheng 1997), and the remaining four trials used a RCT design (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b; Salleras Sanmarti 1993; Kunawararak 2011). Cheng 1997 allocated by day of the week; for Tanke 1994, within each five‐week period each message variation was used once on each weekday and different variations were used each day of a given week by a computer‐generated system. The allocation generation in four RCTs was not clearly documented. In all the included trials on pre‐appointment reminders, concealment of allocation was not clearly documented.

For default reminders, three trials used a RCT design. In both Paramasivan 1993 and Mohan 2003, the generation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment were adequate, while in Krishnaswami 1981, allocation generation and allocation concealment were not clearly documented.

Blinding

The blinding of outcome assessors was adequate in Mohan 2003, inadequate in Paramasivan 1993, and unclear in the seven other trials.

Incomplete outcome data

All the included trials addressed incomplete outcome data adequately, except Salleras Sanmarti 1993, In this trial, 43 out of 318 patients initially enrolled withdrew from the treatment, but the number withdrawn from each group was not stated, nor the reasons for missing data provided.

Selective reporting

It was unclear if any of the included trials was free of selective outcome reporting as the trial protocols were not available and no information on the pre‐specified outcomes was given. However, there was no clear evidence of selective reporting in the included trials and all of the outcomes specified in the trials methods sections were reported.

Other potential sources of bias

Our assessment indicated that the included trials were free of other biases.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

See: Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3 for the main comparisons.

TB treatment

Five trials from India (2), Iraq, Thailand, and the USA, evaluated the effects of reminder policies in people being treated for active TB. Two implemented a policy of pre‐appointment reminders (Tanke 1994; Kunawararak 2011), two implemented a policy of reminders for people who had missed an appointment (default reminders) (Paramasivan 1993; Mohan 2003), and one compared two different forms of default reminders (Krishnaswami 1981). Of these, only two trials stated that DOT was currently being implemented for all patients (Mohan 2003; Kunawararak 2011).

Comparison 1: Reminder versus none

Pre‐appointment reminder

In one trial, pre‐appointment telephone reminders increased clinic attendance from 50% to 66% (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.59, one trial, 615 participants, Analysis 1.1), and it was unclear how treatment was supervised.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TB treatment: reminder versus none, Outcome 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment.

In one small trial from a setting where DOTS was currently implemented, a policy of pre‐appointment telephone reminders increased treatment completion from 88% to 100% (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.27, one trial, 98 participants, Analysis 1.2). This trial provided few details on the process of randomization and is at unclear risk of selection bias. It is significantly underpowered to detect this effect (see Table 6).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TB treatment: reminder versus none, Outcome 2 TB cure or treatment completion.

3. Optimal information size calculations.

| Outcome | Hypothesis | Power | α error | Proportion in control group | Proportion in intervention group | Total sample size required |

| Attendance at clinic appointment | Superiority | 80% | 5% | 50% | 75% | 110 |

| 80% | 90% | 394 | ||||

| TB cure or treatment completion | Superiority | 80% | 5% | 50% | 75% | 110 |

| 80% | 90% | 394 |

We performed calculations using http://www.sealedenvelope.com

Default reminder

In one trial, with low rates of clinic attendance, reminder letters increased clinic attendance from 10% to 52% (RR 5.04, 95% CI 1.61 to 15.78, one trial, 52 participants, Analysis 1.1). In this very small trial treatment was self‐supervised with monthly pick‐up of medications. The findings may not be applicable to situations where treatment is directly observed.

In two further trials, policies of default reminders increased treatment completion from 73% to 88% in a setting without DOTS, and from 83% to 96% in a setting where DOTS was implemented (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.24, two trials, 680 participants, Analysis 1.2). In the first trial, volunteers visited people who had missed an appointment at their own homes to motivate them to attend and provide health education (Mohan 2003). In the second trial, letters were sent on the fourth day after a missed appointment (Paramasivan 1993).

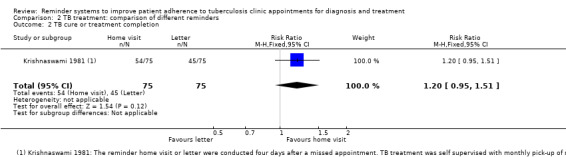

Comparison 2: Different types of reminder (home visit versus letter after a missed appointment)

In one additional trial from a setting without DOTS, there were no statistically significant differences in clinic attendance or treatment completion between a policy of home visits after a missed appointment and a policy of sending reminder letters to people who had missed an appointment (one trial, 121 participants, Analysis 2.1; 150 participants, Analysis 2.2). Treatment completion in this setting was 60% with reminder letters, and 72% with home visits.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 TB treatment: comparison of different reminders, Outcome 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 TB treatment: comparison of different reminders, Outcome 2 TB cure or treatment completion.

TB prophylaxis

Comparison 3: Reminder versus none

Two trials, from the USA and Spain, evaluated reminders for people on TB prophylaxis. In the USA, pre‐appointment telephone reminders increased attendance at a single clinic appointment from 48% to 62.5% (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.59, one trial, 536 participants, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 TB prophylaxis: reminder versus none, Outcome 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment.

In Spain, where children were given 12 months of isoniazid treatment to be supervised at home by their parents, attendance at the final clinic appointment was increased by a policy of routine phone calls every three months (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.72), routine home visits every three months by a specialist nurse (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.74), and by routine doctor clinic appointments every three months (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.47), although this third policy did not quite reach statistical significance (one trial, 318 participants, Analysis 3.2). Forty‐three participants withdrew from treatment; the reasons for their withdrawal and their group allocation were not clear.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 TB prophylaxis: reminder versus none, Outcome 2 Attendance at final clinic appointment.

TB skin test reading

Four trials from the USA evaluated the effectiveness of pre‐appointment reminders on return for tuberculin skin test reading. Two evaluated take home reminder cards (Roberts 1983a; Roberts 1983b), and three evaluated pre‐appointment telephone calls (Roberts 1983a; Tanke 1994; Cheng 1997).

Comparison 4: Reminder versus none

Compared to no reminders, there was little or no effect on attendance for skin test reading for take home reminder cards (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.02, two trials, 711 participants, Analysis 4.1), or for pre‐appointment telephone calls (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.21, three trials, 1189 participants, Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Skin test reading: reminder versus none, Outcome 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment.

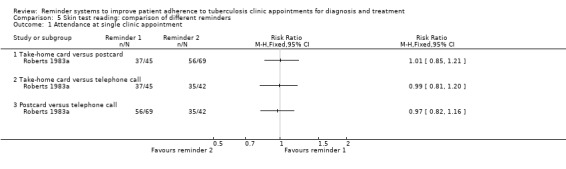

Comparison 5: Comparison of different reminders

In comparisons of different types of reminder, in Roberts 1983a there were no statistically significant differences between take‐home cards, pre‐appointment postcard reminders, or pre‐appointment telephone reminders (one trial, 156 participants, Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Skin test reading: comparison of different reminders, Outcome 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included nine trials, reported in eight papers, in this review. Six trials assessed the use of pre‐appointment reminders and three assessed default reminders.

For people being treated for active TB, clinic attendance and TB treatment completion were higher in people receiving pre‐appointment reminder phone‐calls (low quality evidence). Clinic attendance (low quality evidence) and TB treatment completion (moderate quality evidence) were also higher with default reminders (letters or home visits).

For people on TB prophylaxis, clinic attendance was higher with a policy of pre‐appointment phone‐calls, and attendance at the final clinic was higher with regular three‐monthly phone‐calls or nurse visits.

For people undergoing screening for TB, three trials of pre‐appointment reminder letters or phone‐calls found little or no effect on the proportion of people returning to clinic for the result of their skin test (low quality evidence).

There is inadequate evidence to show differences between different types of pre‐appointment reminders (experts versus non‐experts; take‐home card, a postcard or a telephone call) as well as between different types of default reminders (home visit versus letter).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Almost all the included trials were conducted before or during the 1990s, when DOTS was not yet widely practised. Consequently, some of the findings, especially those from settings where attendance and treatment completion are very low, may be poorly applicable to settings where DOTS is being implemented and adherence is much higher. However, two of the more recent trials were conducted in areas with reasonable levels of treatment completion (Mohan 2003; Kunawararak 2011) and still found clinically important gains through appointment reminders.

There is much interest and enthusiasm in the use of mobile phones to improve patient adherence and attendance, but only one small trial met our inclusion criteria. Mobile telephone use could be used in various ways, for example, to remind patients to take their medicine and keep appointments, to provide knowledge on TB, and to support patients. There are quite a few pilot studies examining the use of mobile telephones in improving TB medication adherence (Visarutrat 2009), but robust evidence on mobile telephone reminders is still insufficient. Once completed, we may include a few ongoing trials evaluating SMS reminders in improving TB adherence in future review updates although not all of them may be relevant to our review (Bediang 2014).

It is important to note that we excluded studies that used bundled interventions from this review (Thiam 2007). Excluding studies that used packaged or multiple interventions implemented under programme conditions limits the generalizability of this review. This also highlights the difficulty of doing systematic reviews of trials that test multiple or combined interventions to improve adherence to long‐term treatment regimens. Future reviews should consider the implementation of interventions under programme settings. Sustainability and duration of effectiveness of the interventions are other important factors to consider in assessing the effectiveness of healthcare interventions aimed at improving adherence. Strategies to improve patient adherence can be divided into patient‐oriented, provider‐oriented, and system interventions.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach and presented the findings in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3.

For people undergoing treatment for active TB, we judged the quality of the evidence that pre‐appointment reminder phone calls improve clinic attendance and TB treatment completion to be of low quality, meaning that further research is very likely to change these estimates of effect. The main reasons for downgrading quality were: 1) risk of bias: none of the trials adequately described methods to prevent selection bias; 2) indirectness: the single trial assessing clinic attendance was from the USA and may be poorly generalized to elsewhere; and 3) imprecision: the single trial reporting TB treatment completion was significantly underpowered to confidently detect this effect.

We also considered the evidence that default reminders improve clinic attendance to be of low quality because the single trial from India was underpowered to detect clinical important effects and the results are not be easily generalized to elsewhere. However, we have more confidence that default reminders improve TB treatment completion and judged this evidence to be of moderate quality. However, the evidence is still limited to just two trials implementing different default reminder systems and further trials would still be useful to improve confidence that the finding can be generalized to elsewhere.

Potential biases in the review process

We minimized potential biases in the review process by adhering to the guidelines of Higgins 2011.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review was published recently to assess the evidence for the use of text messaging to promote adherence to TB treatment, although the four studies included were not on reminder systems for clinic appointments (Nglazi 2013). This review underscored the paucity of high‐quality studies on the effectiveness of text messaging. Our review focused on interventions to remind patients to take their medicine or keep appointments. Hence, we also excluded a recent pilot study (Iribarren 2013) that assessed a text messaging intervention to promote TB treatment adherence. In this study, the SMS intervention was not to remind patients about taking their medication or attend appointments but to remind patients to text the investigators about their intake of medications, to receive patients' questions, and to send educational texts.

A Cochrane Review of patient reminders and recall systems for improving immunization rates showed that all types of reminders were effective (postcards, letters, telephone, or autodialer calls), with telephone being the most effective but most costly (Vann 2005). However, all trials were from high‐income countries.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Policies of sending reminders to people pre‐appointment, and contacting people who miss appointments, seem like sensible additions to any TB program, and the limited evidence available suggests they may have potentially important effects.

Different types of reminders can be tailored to suit specific provider and practice needs. Based on current studies, there is insufficient evidence to assess the differences between different types of reminders. When choosing the type of reminders, some practical issues also need to be considered, such as staffing, transportation, health facilities, perceived accuracy of patient telephone numbers or addresses, availability of computer programmers, overall programme costs, and estimated patient responses to different types of reminders. Practitioners need to consider their own settings when interpreting the findings in this review since these factors vary widely across nations or geographical regions.

Implications for research.

Due to the poor quality of evidence, more well‐designed trials are needed to establish whether pre‐appointment reminders are effective in different settings, and the best way of delivering reminders, especially in low‐income countries. For default reminders, more high quality trials are needed to decide on the most effective reminder actions in different settings. Specifically, future trials should describe carefully the study design, setting, and the details of the intervention, and report primary/clinical health outcomes of the patients, as well as the resource implications. Future studies of modern technologies such as SMS reminders in addition to DOT, or even in replacement of DOT, would be useful, particularly for low‐resource settings.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 September 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The review was updated throughout. |

| 16 September 2014 | New search has been performed | We changed the primary outcomes and added 'Summary of findings' tables; a new search was conducted and new trials added. The review authorship changed. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Regina P. Berba for her valuable contributions to the previous version of this review. Also we are grateful to Paul Garner, Vittoria Lutje, Anne‐Marie Stephani, and Christianne Esparza for their valuable comments and kind support. This review is part of a project funded by UKaid from the UK Government for the benefit of developing countries.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. TB treatment: reminder versus none.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Pre‐appointment phone call | 1 | 615 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.10, 1.59] |

| 1.2 Defaulter reminder letter | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.04 [1.61, 15.78] |

| 2 TB cure or treatment completion | 3 | 778 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [1.11, 1.23] |

| 2.1 Pre‐appointment phone call | 1 | 98 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [1.02, 1.27] |

| 2.2 Defaulter reminder letter or home visit | 2 | 680 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [1.11, 1.24] |

Comparison 2. TB treatment: comparison of different reminders.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment | 1 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.87, 1.45] |

| 2 TB cure or treatment completion | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.95, 1.51] |

Comparison 3. TB prophylaxis: reminder versus none.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment | 1 | 536 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.07, 1.59] |

| 2 Attendance at final clinic appointment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Routine phone call every three months | 1 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.44 [1.21, 1.72] |

| 2.2 Routine nurse home visit every three months | 1 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [1.23, 1.74] |

| 2.3 Routine doctor clinic every three months | 1 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.98, 1.47] |

Comparison 4. Skin test reading: reminder versus none.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment | 4 | 1900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.92, 1.10] |

| 1.1 Take home reminder card | 2 | 711 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.88, 1.04] |

| 1.2 Pre‐appointment phone call | 3 | 1189 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.92, 1.21] |

Comparison 5. Skin test reading: comparison of different reminders.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Attendance at single clinic appointment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Take‐home card versus postcard | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Take‐home card versus telephone call | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Postcard versus telephone call | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cheng 1997.

| Methods | Trial design: Quasi‐RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 627 randomized Inclusion criteria: consecutive children ages 1 to 12 years due for a TB test in an urban children's hospital outpatient department; 1 child per family enrolled Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions | All patients received a written information sheet with the times to return; skin tests were circled in permanent marker and date of return stamped on mother's and child's hands All families received education regarding the importance of skin testing for TB and the need for follow‐up to read the results. Instructions were given to return to the clinic in 48 to 72 hours Intervention of interest:

Control:

Other interventions not included in this review:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review :

|

|

| Notes | Location: USA Trial dates: not specified Baseline data: comparable Funding: Ambulatory Pediatrics Association |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomized by day of the week. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Sequential allocation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 627/627 (100%), no missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Krishnaswami 1981.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 170 randomized; 150 analysed Inclusion criteria: patients with symptoms reporting at the Institute of Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases in Madras; with radiographic evidence of TB but negative smears; aged ≥ 12 years; prescribed national TB programme recommended regimen; living within a radius of about 5 km from the clinic; bona fide residents of Madras city and regarded as stable (expected to remain in the city for at least 1 year) Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: South India Trial dates: not specified Funding: Indian Council of Medical Research Baseline data: comparable |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 150/170 (89%); 20 participants excluded from main analysis because of death (8), lost to follow‐up (6), chemotherapy change (3), or transfer to more accessible clinics (3), but missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Kunawararak 2011.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 98 randomized Inclusion criteria: patients aged > 15 years diagnosed with MTB who had never been treated with second line TB drugs, patients in whom DST and HIV testing were performed and whose liver function tests were lower than 2 times the upper limits of normal. Exclusion criteria: pregnant patients, MDR‐TB patients resistant to 3 or more of 6 classes of second‐line drugs, patients with history of epilepsy or alcoholism, patients who could not answer questions by the researcher and patients who could not complete the treatment. |

|

| Interventions | All patients had DOTS Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: Northern Thailand Trial dates: April 2008 to December 2009 Baseline data: comparable Funding: Graduate School of Chulalongkorn University, and the Department of Disease Control, MInistry of Public Health, Thailand |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data, 98/98 (100%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Mohan 2003.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 480 randomized Inclusion criteria: new smear‐positive PTB; never been treated previously; delayed coming to collect drugs at the health centre for at least 3 days after scheduled appointment; identified from official patient record cards Exclusion criteria: re‐treatment patients |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: Iraq Trial dates: May 2001 to May 2002 Baseline data: not reported Funding: the EMRO/DCD/TDR Small Grants Scheme for Operational Research in Tropical and Communicable Diseases |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | By random‐numbers table (confirmed by the trial authors). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Using sequentially numbered and sealed opaque envelopes (confirmed by the trial authors). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The evaluation was blind as the information about outcome was collected by a field worker who did not know which group the patients were assigned to. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data, 480/480 (100%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Paramasivan 1993.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 200 randomized Inclusion criteria: newly diagnosed adult PTB patients; sputum positive for acid‐fast bacilli (AFB); no treatment or < 15 days previous treatment; not in moribund condition or suffering from disorders like diabetes, cardiac failure, or renal failure; willing to stay in the hospital for the initial 1‐month intensive phase of treatment Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: South India Trial dates: not specified Baseline data: not reported Funding: the Scientific Committee of Anti‐tuberculosis Association of Tamilnadu |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random‐numbers table (confirmed by the trial authors). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralized randomization by a third party (confirmed by the trial authors). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of outcome assessment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 200/200 (100%), no missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Roberts 1983a.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 200 randomized Inclusion criteria: volunteers who participated in a university‐sponsored TB detection drive; mostly college students Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review : None. |

|

| Notes | Location: USA Trial dates: not specified Baseline data: comparable Funding: Research Grants Committee, University of Alabama |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 200/200 (100%), no missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Roberts 1983b.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 553 randomized Inclusion criteria: volunteers who participated in a university‐sponsored TB detection drive Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review : None. |

|

| Notes | Location: USA Trial dates: not specified Baseline data: comparable Funding: Research Grants Committee, University of Alabama |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 553/553 (100%), no missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Salleras Sanmarti 1993.

| Methods | Trial design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 318 randomized Inclusion criteria: school children of both sexes in the first year of primary school in state‐run and private schools in the provinces of Barcelona, on anti‐TB chemoprophylaxis Exclusion criteria: children with active TB confirmed by medical examination and chest x‐ray |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

|

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: Spain Trial dates: academic year 1985 to 1986 Baseline data: not reported Funding: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only described as "randomised". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 275/318 (86.5%); 43/318 (13.5%) withdrew from treatment, but number withdrew from each group not stated, nor reasons for missing data provided. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Tanke 1994.

| Methods | Trial design: Quasi‐RCT | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 2008 randomized Inclusion criteria: patients with scheduled appointments in the Tuberculosis Control Program of Santa Clara County Health Department over a period of 6 months Exclusion criteria: not stated |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention of interest:

Control:

Appropriate recorded message was sent to patients between 18.00 and 21.00 the evening before the scheduled appointment. The system allows a message to be left on answering machines and to call back up to 5 times at half‐hour intervals if patients' lines were busy or there was no answer after 8 rings. For households whose primary language was English, Spanish, Vietnamese, or Tagalog, the message was sent in that language. |

|

| Outcomes |

Outcomes included in this review:

Outcomes not included in this review :

|

|

| Notes | Location: USA Trial dates: not specified Baseline data: not reported Funding: SBIR grants #2 R44 AI31750‐02 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and #1 R43 AG10659‐01 from the National Institute on Aging |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Within each 5‐week period each message variation was used once on each weekday, different variations were used each day of a given week by a computer‐generated system. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Sequential allocation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 2008/2008 (100%), no missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section are reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ailinger 2010 | Pre‐experimental design with historical comparison, cultural intervention with no reminder. |

| Akhtar 2011 | Clinic DOT versus family DOT, did not mention the intervention of interest. |

| Al‐Hajjaj 2000 | Case‐control study design. |

| Alcaide Megías 1990 | Intervention did not include reminders. |

| Alvarez Gordillo 2003 | Intervention did not include reminders. |

| Atkins 2011 | Enhanced Tuberculosis Adherence (ETA) model versus DOT, ETA is a complex intervention contains treatment supporter visits but the results cannot be disaggregated. |

| Barclay 2009 | Report. |

| Bordley 2001 | Most participants did not have need for screening, prophylaxis or treatment for TB, and results for the individuals in these categories were not presented separately. |

| Bronner 2012 | A retrospective study using routinely collected data from the South African national database for TB surveillance. |

| Grant 2010 | Description on community education and mobilization of a TB preventive programme, reminder is not a main component of the integrated intervention package. |

| Hovell 2003 | Intervention did not include reminders. |

| Hsieh 2007 | The study evaluated case management that includes in‐hospital direct supervision plus a home visit on discharge. |