Abstract

Aromatic hydroxylations are important bacterial metabolic processes but are difficult to perform using traditional chemical synthesis, so to use a biological catalyst to convert the priority pollutant benzene into industrially relevant intermediates, benzene oxidation was investigated. It was discovered that toluene 4-monooxygenase (T4MO) of Pseudomonas mendocina KR1, toluene 3-monooxygenase (T3MO) of Ralstonia pickettii PKO1, and toluene ortho-monooxygenase (TOM) of Burkholderia cepacia G4 convert benzene to phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene by successive hydroxylations. At a concentration of 165 μM and under the control of a constitutive lac promoter, Escherichia coli TG1/pBS(Kan)T4MO expressing T4MO formed phenol from benzene at 19 ± 1.6 nmol/min/mg of protein, catechol from phenol at 13.6 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg of protein, and 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene from catechol at 2.5 ± 0.5nmol/min/mg of protein. The catechol and 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene products were identified by both high-pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. When analogous plasmid constructs were used, E. coli TG1/pBS(Kan)T3MO expressing T3MO formed phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene at rates of 3 ± 1, 3.1 ± 0.3, and 0.26 ± 0.09 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively, and E. coli TG1/pBS(Kan)TOM expressing TOM formed 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene at a rate of 1.7 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg of protein (phenol and catechol formation rates were 0.89 ± 0.07 and 1.5 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively). Hence, the rates of synthesis of catechol by both T3MO and T4MO and the 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene formation rate by TOM were found to be comparable to the rates of oxidation of the natural substrate toluene for these enzymes (10.0 ± 0.8, 4.0 ± 0.6, and 2.4 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg of protein for T4MO, T3MO, and TOM, respectively, at a toluene concentration of 165 μM).

Benzene is a widely used chemical produced mainly from petroleum and coal tar (13). It is one of the top 20 chemicals in the United States in terms of production volume, is listed in at least 57% of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Superfund sites (http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/tfacts3.html), and is considered a priority pollutant by the Environmental Protection Agency (http://www.envirobrowser.com/pollute_q.jsp). Long-term benzene exposure affects bone marrow and can cause anemia and leukemia (16, 30); therefore, benzene should be removed from contaminated sites. Monooxygenases may be used to hydroxylate and remove benzene, but since phenol, the monohydroxylated product, is also listed as a priority pollutant, double hydroxylation of benzene to catechol is more efficient for combining bioremediation and biocatalysis.

Catechols are important intermediates for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, flavors, polymerization inhibitors, and antioxidants (10, 11). Currently, catechol is produced primarily by the oxidation of phenol and m-diisopropylbenzene or by coal-tar distillation (13). However, the industrial routes to catechols, e.g., the use of elevated metal, temperature, pressure, and solvent conditions, are environmentally unsafe (1, 13). These chemical routes are often lengthy, energy-intensive, multistep reactions that require expensive starting materials and are plagued with isomerization and rearrangement problems (1, 25); hence, microbial production of catechols is attractive. Previously, catechol has been produced by transforming d-glucose with a genetically modified Escherichia coli AB2834/pKD136/pKD9.069A strain expressing 3-dehydroshikimic acid dehydratase and protocatechuic acid decarboxylase (10, 11) and by benzene oxidation with Pseudomonas putida 6-12 expressing toluene/benzene dioxygenase while lacking catechol 1,2-oxygenase and catechol 2,3-oxygenase (25).

Toluene 4-monooxygenase (T4MO) of Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 (32), toluene 3-monooxygenase (T3MO) of Ralstonia pickettii PKO1 (5), toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase (ToMO) of Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 (3), and toluene ortho-monooxygenase (TOM) of Burkholderia cepacia G4 (21) belong to the family of diiron monooxygenases (17). TOM of B. cepacia G4 oxidizes toluene to o-cresol and then to 3-methylcatechol (21) while appearing to transform benzene to phenol and then to catechol (29), although this has been challenged (21). ToMO of P. stutzeri OX1 oxidizes toluene to 3- and 4-methylcatechol and converts o-xylene into 3,4-dimethylcatechol but is reported to transform benzene only to phenol (2). T4MO of P. mendocina KR1 and T3MO of R. pickettii PKO1 have been reported to convert benzene to phenol and toluene to p-cresol and m-cresol (11a, 22, 24), respectively, but have not been shown previously to perform successive hydroxylations on aromatics (17, 20, 22, 24).

T4MO (32) and T3MO (5) are four-component enzymes consisting of an (αβγ)2 hydroxylase (from tmoABE and tbuA1A2U, respectively), a NADH oxidoreductase (from tmoF and tbuC, respectively), a Rieske-type (2Fe-2S) ferredoxin (from tmoC and tbuB, respectively), and an effector protein (from tmoD and tbuV, respectively), while TOM (21) consists of an (αβγ)2 hydroxylase (from tomA1A3A4), a NADH oxidoreductase (from tomA5), an effector protein (from tmoA2), and a relatively unknown subunit (from tomA0). The T3MO tbu locus is most similar (>60%) to T4MO tmo genes in the DNA sequence (18), but both T4MO and T3MO are only distantly related to TOM and are substantially different enzymes (as evidenced by their different hydroxylations of toluene) since the hydroxylase alpha fragments of T3MO and T4MO share only 48% DNA homology and only 23% protein identity with TOM.

The goal of this study was to characterize the ability of wild-type aromatic monooxygenases to hydroxylate benzene; it was found that T4MO and T3MO are capable of successive hydroxylations of benzene to form phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene (1,2,3-THB) and that TOM converts catechol to 1,2,3-THB. Hence, five previously unknown reactions have been characterized in terms of rates and product identification (phenol to catechol and catechol to 1,2,3-THB by T4MO and T3MO and catechol to 1,2,3-THB by TOM), and their oxidation rates have been compared to that of toluene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Benzene (99%), phenol (99%), and catechol (99+%) were obtained from Fisher Scientific Co. (Fairlawn, N.J.). Hydroquinone (99%) was obtained from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, N.J.). Resorcinol (98%), 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene (1,2,4-THB) (99%), and 1,2,3-THB (98%) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). All materials used were of the highest purity available and were used without further purification.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli TG1 {supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15]} was routinely cultivated with the plasmid constructs at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm on a C25 incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Edison, N.J.) in Luria-Bertani medium (26) supplemented with kanamycin at 100 μg/ml to maintain the plasmids. All experiments were conducted by diluting overnight cells to an optical density at 600 nm (OD) of 0.1 to 0.2 and growing to an OD of 1.2. The exponentially grown cells were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min at 25°C in a J2-HS centrifuge (Beckman, Palo Alto, Calif.) and resuspended in Tris-HNO3 buffer (50 mM; pH 7.0) or potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM; pH 7.0).

Protein analysis and molecular techniques.

A Total Protein kit (Sigma Chemical Co.) was used to determine the total cellular protein of E. coli TG1 pBS(Kan)T4MO [henceforth TG1(T4MO)] and E. coli TG1 pBS(Kan)T3MO [TG1(T3MO)] for calculating whole-cell specific activities. The total protein concentration of E. coli TG1 pBS(Kan)TOM [henceforth TG1(TOM)] was determined previously (7). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a Midi or Mini kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.), and a GeneClean III kit (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.) was used to isolate DNA fragments from agarose gels. E. coli strains were electroporated using a GenePulser and a Pulse Controller (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) at 15 kV/cm, 25 μF, and 200 Ω.

Construction of expression vectors.

To stably and constitutively express the toluene monooxygenase genes from the same promoter, the expression vectors pBS(Kan)T4MO, pBS(Kan)T3MO, and pBS(Kan)TOM were constructed. The construction of pBS(Kan) and pBS(Kan)TOM was described previously (7); note that our wild-type TOM (AF349675) used here has one amino acid (D14N in tomA3) that differs from that in the TOM sequence in GenBank (AF319657), but this mutation has no effect on activity. To create pBS(Kan)T4MO, a 4.7-kbp DNA fragment including the tmoABCDEF genes was PCR amplified from plasmid pMY486 (34) with a mixture of Taq and Pfu polymerases (1:1) and primers T4MOEcoRIFront (Table 1) and T4MOBamHIRear (Table 1) and cloned into the multiple cloning site in pBS(Kan) after double digestion with EcoRI and BamHI.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for cloning and sequencing of the T4MO tmoABCDEF locus of P. mendocina KR1 and the T3MO tbuA1UBVA2C locus of R. pickettii PKO1

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|

| Cloning primers | |

| T4MOEcoRIFront | 5′-TACGGAATTCAAGCTTT TAAACCCCACAGG-3′ |

| T4MOBamHIRear | 5′-TTCGGATCCGCTGAGAA CACATTGAACAGG-3′ |

| T3MOBamHIFront | 5′-TGAGGGATCCCGCCAAG CAAAAAACACTAC-3′ |

| T3MOXbalRear | 5′-AAGTTCTAGAGTCGATG CTGTGCTGTGTCC-3′ |

| Sequencing primers | |

| T4MOEcoRIFront | 5′-TACGGAATTCAAGCTTT TAAACCCCACAGG-3′ |

| T4MO1 | 5′-CCCGCATGAATACTGTA AGAAGGATCGC-3′ |

| T4MO2 | 5′-GCTCGTTGATAGATCTG GGCTTGGACAA-3′ |

| T4MO3 | 5′-AATCTATTGAAGAGATG GGCAAAGACGC-3′ |

| T4MO4 | 5′-TCCGATGGTACCGAA GTC-3′ |

| T4MO5 | 5′-GGCGAACTGATATTGAC TCG-3′ |

| T4MO6 | 5′-CAATGGCCCGCTGTTA TTC-3′ |

| T4MO7 | 5′-GAAGGTTGGATTGAAAA GTGG-3′ |

| T4MO8 | 5′-TGCAAACCATTATCCGA CCTC-3′ |

| T4MO9 | 5′-CTGATTAATGTGTCGTC GAGC-3′ |

| T3MOBamHIfront | 5′-TGAGGGATCCCGCCAA GCAAAAAACACTAC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuA1 | 5′-ATTTCCCGCACGACTAT TGC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuA2 | 5′-AACGCACCTTGATCGAC CTG-3′ |

| T3MOtbuA3 | 5′-GCTTCAGTACATGAACC TGGC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuB1 | 5′-TGCGTTCCAGGGAATCT GCC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuV1 | 5′-CGACTACGTCCGCTTCT AC3′ |

| T3MOtbuA4 | 5′-ATCTCGAACTGCGCGGC GTAC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuA5 | 5′-GGTGCGCGAGTTCCGGC AC-3′ |

| T3MOtbuC1 | 5′-AGTACGCGCTGCTGTAT CCG-3′ |

To create pBS(Kan)T3MO, a 4.6-kbp DNA fragment including the tbuA1UBVA2C genes was PCR amplified from plasmid pRO1966 (5, 22) with a mixture of Taq and Pfu polymerases (1:1) and primers T3MOBamHIFront (Table 1) and T3MOXbaIRear (Table 1). The PCR product was cloned into the multiple cloning site in pBS(Kan) after double digestion with BamHI and XbaI.

In pBS(Kan)T4MO, pBS(Kan)T3MO, or pBS(Kan)TOM, the lac promoter yields constitutive expression of T4MO, T3MO, or TOM due to the high copy numbers of the plasmid and lack of the lacI repressor. Expression of wild-type T4MO from pBS(Kan)T4MO and T3MO from pBS(Kan)T3MO within E. coli strains produced blue-colored cells on agar plates and in broth cultures, but expression of wild-type TOM from pBS(Kan)TOM within E. coli strains produced the normal brown-colored cells on agar plates and in broth cultures (19, 28).

Enzymatic activity.

Successive hydroxylation activity levels of TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) were determined by a colorimetric assay and high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Concentrated cell suspensions (2 ml) (OD, 2 to 10) in Tris-HNO3 buffer were contacted with 165 μM substrate (benzene, phenol, or catechol dissolved in 99.5% ethanol; for benzene, 400 μM substrate was added as if all were in aqueous phase as determined on the basis of a Henry's law constant of 0.22) (9) in 15-ml serum vials sealed with a Teflon-coated septum and aluminum crimp seal. The negative controls used in these experiments contained the same monooxygenase without substrates (plus solvent) as well as TG1/pBS(Kan) with substrates (no monooxygenase control). The inverted vials were shaken at room temperature at 300 rpm on an IKA-Vibrax-VXR shaker (IKA-Works, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) for 4 min to 4 h, and then 1 ml of the cell suspension was removed and centrifuged in a 16 M Spectrafuge (Labnet, Edison, N.J.) for 1 to 2 min. The supernatant was analyzed by the colorimetric assay for catechol and by HPLC for the identification and quantification of all intermediates.

For benzene and toluene oxidation activity, 2 ml of concentrated cell suspensions in Tris-HNO3 buffer or in phosphate buffer were sealed in 15-ml serum vials, and 400 μM benzene or 455 μM toluene, calculated as if all the substrate were in the liquid phase (the actual initial liquid concentration was 165 μM as calculated on the basis of Henry's law) (9), was added to the vials with a syringe. The inverted vials were shaken at room temperature at 300 rpm. The reaction was stopped by injecting 2 ml of ethyl acetate containing 500 μM hexadecane (the internal standard) to the vial, and the vial was vortexed thoroughly to ensure full extraction of the toluene. The organic phase was separated from the aqueous phase by centrifugation, and 2 to 3 μl was injected to the gas chromatograph (GC) column. Activity data reported in this paper are in the form of the mean ± 1 standard deviation (based on at least two independent results).

Catechol colorimetric assay.

The catechol generated by whole cells from the biotransformation of benzene or remaining after the catechol oxidation experiments was measured spectrophotometrically by modifying the procedure of Fujita et al. for 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes (12); this assay measures catechol on the basis of the color reaction of catechol, iron (III), and phenylfluorone (a xanthene dye), and phenol does not interfere with this assay whereas 1,2,3-THB interferes slightly (yielding 5% of the catechol signal).

The catechol concentration was measured by adding 300 μl of 0.1 M sodium carbonate-0.1 M sodium hydrogen carbonate buffer, 100 μl of 5% polyoxyethelene monolauryl ether (Acros Organics), 60 μl of 1 mM iron (III) ammonium sulfate, 60 μl of 1 mM phenylfluorone (Acros Organics) in methanol, and 380 μl of sterile water to the 100 μl of supernatant for a 1.0-ml final volume in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube. After 1 min, the absorbance of the color complex (catechol-FeIII-phenylfluorone) at 630 nm was measured using a UVmini-1240 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The molar amount of catechols was calculated by comparison to a catechol standard curve (the measured molar extinction coefficient was 22,600 M−1 cm−1). The minimum detectable catechol concentration with this method was 10 μM.

Analytical methods.

Reverse-phase HPLC was conducted to analyze TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) samples for the conversion of benzene to phenol, phenol to catechol, and catechol to 1,2,3-THB. Filtered samples were injected into a Zorbax SB-C8 column (Agilent Technologies) (4.6- by 250-mm, 5-μm particle size) with a Waters Corporation (Milford, Mass.) 515 solvent delivery system coupled to a photodiode array detector (Waters 996). The gradient elution was performed with H2O (0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile (70:30, 0 to 8 min; 40:60, 15 min; 70:30, 20 min) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Under these conditions, the retention times for phenol, catechol, resorcinol, and hydroquinone standards were 9.6, 5.9, 5.0, and 4.3 min, respectively, and the absorbance maxima were 269, 276, 274, and 291 nm, respectively. For detection of 1,2,3-THB, an isocratic mobile phase of H2O (0.1% formic acid)-acetonitrile (90:10) was used; under these conditions, the retention times for catechol, 1,2,3-THB, and 1,2,4-THB were 12.6, 6.0, and 4.5 min, respectively, and the absorbance maxima were 276, 265, and 290 nm, respectively. Compounds were identified by comparison of retention times and UV-visible spectra to those of authentic standards as well as by coelution with the standards.

The identities of catechol and 1,2,3-THB were confirmed by reverse-phase LC-mass spectrometer (LC-MS) using a Hewlett-Packard (Palo Alto, Calif.) 1090 series II LC with a diode array detector coupled to a Micromass Q-TOF2 (Beverly, Mass.) MS. Separation of catechol from benzene and phenol was achieved using a Zorbax SB-C18 column (2.1- by 150-mm, 3-μm particle size) with a mobile phase consisting of H2O (0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile and a gradient elution at 0.3 ml/min starting at 100% H2O (0.1% formic acid) and changing to 0% in 12 min, with a 3-min hold at the final composition. Separation of 1,2,3-THB from catechol was achieved using a mobile phase consisting of 90% H2O (0.1% formic acid) and 10% acetonitrile. The Q-TOF2 was operated in negative-ion electrospray mode with 3.0 kV applied to the inlet capillary and 75 V applied to the extraction cone.

Benzene and toluene concentrations were measured by GC using a Hewlett-Packard 6890N GC equipped with an EC-WAX capillary column (Alltech Associates, Inc., Deerfield, Ill.) (30 m by 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm thickness) and a flame ionization detector. The injector and detector were maintained at 250 and 275°C, respectively. The detection of benzene was achieved with a split ratio of 1:1 and helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The temperature program was 50°C for 6 min followed by 50 to 250°C at a rate of change of 20°C/min. Under these conditions, benzene eluted at 5.1 min whereas the internal standard hexadecane eluted at 13.8 min. Separation of toluene oxidation products was achieved with a split ratio of 3:1 and helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The temperature program for toluene oxidation was 80°C for 5 min, 80 to 205°C at a rate of change of 5°C/min, 205 to 280°C at 15°C/min, and 280°C for 5 min. Under these conditions, toluene and o-, p-, and m-cresols eluted at 4.2, 27.6, 29.3, and 29.5 min, respectively, whereas the internal standard hexadecane eluted at 17.8 min.

DNA sequencing.

A dideoxy chain termination technique (27) was used with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) and an ABI 373 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) to determine the T4MO and T3MO nucleotide sequence. A total of 10 primers (Table 1) 19 to 32 bp in length were generated from the wild-type T4MO sequence (GenBank M65106) (35) and M95045 (34) for sequencing T4MO tmoABCDEF in one direction, and 9 primers (Table 1) 19 to 29 bp in length were designed on the basis of the wild-type T3MO sequence (GenBank U04052 (5) for sequencing T3MO tbuA1UBVA2C. Sequence data generated were analyzed using Vector NTI software (InforMax, Inc., Bethesda, Md.).

RESULTS

Benzene oxidation intermediates.

By analyzing benzene oxidation via a colorimetric assay, it was discovered that catechol was formed from benzene by TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) (results not shown). To corroborate these results, supernatants of TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), or TG1(TOM) cultures (exponentially grown on Luria-Bertani medium-kanamycin and reacted with 165 μM benzene) were analyzed directly by reverse-phase HPLC, and two reaction products for both TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) were detected using benzene that coeluted with authentic phenol and catechol standards and had the same UV-visible spectra. Phenol is known to be the intermediate of benzene oxidation by T4MO (24) and T3MO (22); thus, no further work was performed to confirm the identity of the phenol product. LC-MS analysis further confirmed the identity of catechol by comparison of its mass spectrum with that of authentic catechol (major fragment ion at m/z 109 [M-1]).

It was observed from both HPLC and the colorimetric assay that the catechol concentration as a result of benzene oxidation decreased after reaching a maximum for TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) (results similar to those of Fig. 1), which suggested that catechol intermediates preceded a third oxidation product from benzene. HPLC results showed that 1,2,3-THB was produced from catechol by TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM); note that it was clear on the basis of its different retention time and UV-visible spectrum that the product was not 1,2,4-THB. LC-MS also confirmed the identity of that peak, which gave the same mass spectrum as that of authentic 1,2,3-THB (major fragment ion at m/z 125 [M-1]).

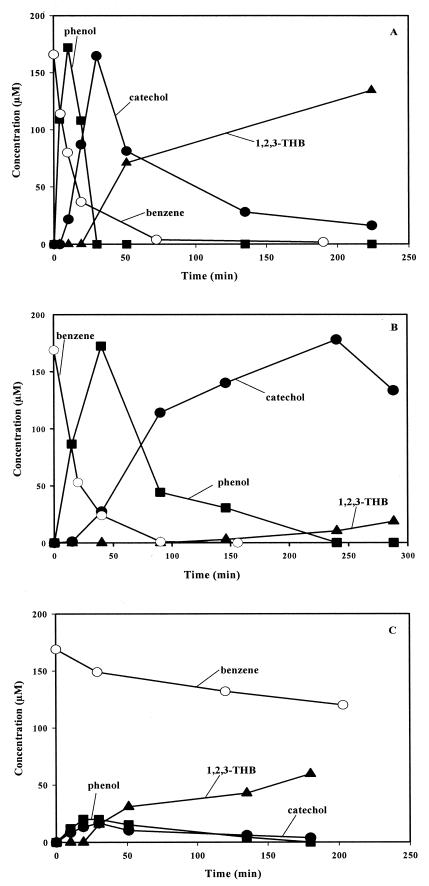

FIG. 1.

Time course of hydroxylated product formation from benzene determined by HPLC and of liquid benzene disappearance determined by GC from exponentially growing TG1(T4MO) (A), TG1(T3MO) (B), and TG1(TOM) (C). The initial liquid benzene concentration was 165 μM (400 μM benzene was added as if all were in the liquid phase). Representative figures of at least two independent results are shown.

Time course of benzene oxidation.

Successive hydroxylation activity of TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) was determined by GC analysis of benzene disappearance and by HPLC analysis of the hydroxylated products formed from 165 μM benzene after a contact period of 4 min to 4 h (Fig. 1). The HPLC catechol concentrations were also corroborated by analogous, independent experiments using the colorimetric assay. The time course of benzene oxidation by TG1(T4MO) (Fig. 1A) showed that along with the decrease of benzene, the three intermediates (phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-THB) formed sequentially. Phenol concentrations transiently accumulated and then rapidly subsided as catechol was produced following the synthesis of 1,2,3-THB, which was relatively slow (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, TG1(T3MO) demonstrated a similar pattern of product formation but showed relatively slower formation rates. TG1 expressing TOM, which is known to perform double hydroxylations of toluene to 3-methylcatechol (21), accumulated low concentrations of phenol and catechol but relatively high concentrations of 1,2,3-THB (Fig. 1C). The negative control TG1/pBS(Kan) lacking a monooxygenase did not produce any product under these conditions (data not shown); therefore, phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-THB produced from benzene were from the expression of the cloned T4MO enzyme of P. mendocina KR1, the cloned T3MO enzyme of R. pickettii PKO1, and the cloned TOM enzyme of B. cepacia G4.

Phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-THB formation rates.

Analysis by both HPLC (Fig. 1) and by the colorimetric assay (results not shown) revealed that benzene is converted to phenol and catechol and subsequently to 1,2,3-THB. To quantify the rates of transformation, the initial reaction rates of the transformation of benzene to phenol, phenol to catechol, and catechol to 1,2,3-THB at an initial concentration of 165 μM for all substrates were investigated using TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) and HPLC (Table 2). All the synthesis rates were corroborated by the corresponding substrate consumption rates; for example, the benzene disappearance rates for TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) found by independent experiments using GC, 19 ± 1 and 2.9 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively, were consistent with the phenol formation rates obtained by HPLC, 19 ± 1.6 and 3 ± 1 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Synthesis of phenol from benzene, catechol from phenol, and 1,2,3-THB from catechol by E. coli TG1 cells expressing wild-type T4MO, T3MO, and TOMa

| Enzyme | Phenol formation from benzene

|

Catechol formation from phenol

|

1,2,3-THB formation from catechol

|

Toluene oxidation rate (nmol/min/mg protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial formation rate (nmol/min/mg of protein) | Maximum production (μM) | Initial formation rate (nmol/min/mg of protein) | Maximum production (μM) | Initial formation rate (nmol/min/mg protein) | Maximum production (μM) | ||

| T4MOb | 19 ± 1.6 | 144 ± 47 | 13.6 ± 0.3 | 103 ± 10 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 132 ± 22 | 10 ± 0.8 |

| T3MOb | 3 ± 1 | 122 ± 43 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 119 ± 13 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 73 ± 4 | 4 ± 0.6 |

| TOMc | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 27 ± 12 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 140 ± 7 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 103 ± 22 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

As determined on the basis of HPLC analysis, the means ± standard deviations of at least two independent results are shown. The initial benzene liquid concentration was 165 μM on the basis of a Henry's law constant of 0.22 (9) (a 400 μM concentration was added as if all the benzene was in the liquid phase), and the initial toluene concentration was 165 μM on the basis of a Henry's law constant of 0.27 (9) (a 455 μM concentration was added as if all the toluene was in the liquid phase).

Protein concentration, 0.24 mg of protein/ml·OD.

Protein concentration, 0.22 mg of protein/ml·OD.

In addition, the rates of catechol formation from phenol (Table 2) were corroborated by independent HPLC experiments in which the rates of synthesis of catechol from benzene were measured [initial formation rates of catechol from benzene for TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) were measured to be 5.3 ± 0.2, 1.3 ± 0.7, and 0.9 ± 0.2 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively]. Note that the rates of catechol formation from benzene were two times slower than those from phenol, because conversion of benzene to catechol was a two-step reaction requiring adequate concentrations of the phenol intermediate to accumulate before a significant amount of catechol was formed.

Of the strains tested, the initial rates of phenol formation from benzene, catechol formation from phenol, and l,2,3-THB formation from catechol were highest for TG1(T4MO) (Table 2). Both benzene and phenol were equally good substrates for T4MO (and equally good for T3MO except that the rates were about fivefold lower than those seen with T4MO); however, for 1,2,3-THB formation, TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) oxidized catechol 5 to 12 times slower than they oxidized benzene and phenol. TG1(TOM) showed comparable rates of reaction for all three substrates (Table 2); hence, no large amounts of phenol or catechol accumulated as with TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) (Fig. 1). Rates of phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-THB synthesis were sustainable, as shown in Fig. 1, and for TG1(T4MO) the yields were comparable to the initial benzene concentration (Table 2). T4MO does not appear to oxidize 1,2,3-THB further (results not shown).

Catechol in the presence of live, negative-control TG1/ pBS(Kan) cells or in Tris-HNO3 buffer (pH 7.0) without cells was stable during the time scale of these experiments (up to 4 h). 1,2,3-THB was found to be unstable in the buffer system and turned brown rapidly (100% degraded after 2 h); however, 1,2,3-THB in the presence of live TG1/pBS(Kan) cells was relatively stable, with no degradation during the first 30 min, and 15 to 60% of 1,2,3-THB was degraded after 1 to 4 h. Hence, the time points for the initial rate data (Table 2) were taken in less than 30 min for 1,2,3-THB and less than 1 h for catechol to minimize abiotic degradation and to accurately measure the oxidation rates.

Toluene oxidation.

To compare the newly discovered catechol and 1,2,3-THB formation rates to the rate of oxidation of toluene, the natural substrate, cells were contacted with 165 μM toluene (initial concentration as calculated on the basis of Henry's law) and the initial rate of toluene disappearance was monitored using GC (Table 2). These toluene oxidation rates (2.4 to 10 nmol/min/mg of protein) are similar to the formation rates of phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-THB (with the exception of 1,2,3-THB synthesis from T3MO); hence, the newly discovered catechol and 1,2,3-THB activities of these enzymes are significant (Table 2).

Corrections to the T4MO and T3MO gene sequences.

The entire wild-type T4MO locus from the plasmid pBS(Kan)T4MO and the entire T3MO locus from the plasmid pBS(Kan)T3MO were sequenced as was well as the comparable regions of the original vectors used to first characterize these enzymes (pMY486 as the source for the T4MO locus [34, 35] and pRO1966 as the source for the T3MO locus [5, 22]). There were no changes in the DNA sequence due to cloning into pBS(Kan); however, three coding sequencing errors were identified in the published DNA sequences of T4MO (34, 35), and all three alterations were in the hydroxylase genes (codons 336 and 337 of tmoA should be changed from TTG GAC to TGG TAC [TmoA L336W and D337Y] [boldface characters indicate alterations henceforth] and codon 310 of tmoE should be changed from CAC to CCC [TmoE H310P]). The corrected sequences were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; GenBank accession number AY552601). Three coding sequencing errors were also identified in the published T3MO sequences (5): codons 33 and 34 of tbuB should be changed from CGA AGG to GAA GGG (TbuB R33E and R34G) and codon 29 of tbuC should be changed from GGC to GCC (TbuC G29A). The corrected sequences were also deposited (GenBank accession number AY541701). Each of the changes was verified twice for each plasmid by using a dideoxy chain terminator. The TmoA L336W sequence change makes T4MO match the equivalent residue in both ToMO and T3MO (both have tryptophan), and the sequence change D337Y in T4MO tmoA matches the equivalent residue in the ToMO touA gene. The TbuB R33E and TbuC G29A changes make T3MO match the equivalent residues in T4MO TmoC and TmoF.

DISCUSSION

Previously, it was reported that P. mendocina KR1 utilizes toluene as a sole carbon and energy source, converting it to p-cresol via T4MO (33). This single hydroxylation is followed by oxidation of the methyl group by p-cresol methylhydroxylase and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase, resulting in p-hydroxybenzoate, which is oxidized to protocatechuate (33). Protocatechuate is metabolized through an ortho-cleavage pathway (33). R. pickettii PKO1 metabolizes benzene and toluene to phenol and m-cresol, respectively, via T3MO (6). Phenol and m-cresol are then further oxidized by phenol hydroxylase to catechol and 3-methylcatechol, respectively, which are then cleaved by a meta-fission dioxygenase (6). Therefore, it was surprising to find here that T4MO and T3MO further oxidize phenol and catechol as they do not appear to be physiologically relevant reactions.

At least four monooxygenases capable of successive hydroxylations of aromatics have been found. TOM (21) and toluene/benzene 2-monoxygenase of Burkholderia sp. strain JS150 (14) transform toluene to o-cresol and then o-cresol to 3-methylcatechol. p-Nitrophenol monooxygenase from Burkholderia sphaericus JS905 converts p-nitrophenol to 4-nitrocatechol and then removes the nitro group and forms 1,2,4-THB (15). ToMO also catalyzes toluene or o-xylene into methylcatechols by two subsequent monooxygenations (2).

Before this report, on the basis of their ability to perform successive hydroxylations, TOM and toluene/benzene 2-monooxygenase were thought to be most similar to phenol hydroxylases rather than to other toluene monooxygenases (17, 20); however, in this study, the accumulation of catechol from benzene by TG1(T4MO) and TG1(T3MO) encoding T4MO and T3MO, respectively, indicates that these two monooxygenases possess a sequential hydroxylation pathway similar to that of TOM of B. cepacia G4 (21), ToMO of P. stutzeri OX1 (2), and toluene/benzene 2-monoxygenase of Burkholderia sp. strain JS150 (14). The catechol formed from benzene by the two successive hydroxylations by TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM) was further oxidized to 1,2,3-THB. In addition, ToMO of P. stutzeri OX1 was also found in our laboratory to make 1,2,3-THB by use of constitutive expression from an analogous construct, pBS(Kan)ToMO (32a). Further hydroxylation of catechol to 1,2,3-THB has not been reported previously for these four monooxygenases (T4MO, T3MO, TOM, and ToMO). THB products have been seen previously, since 4-nitrocatechol can be degraded via 1,2,4-THB by B. cepacia RKJ200 (8) or by B. sphaericus JS905 (15).

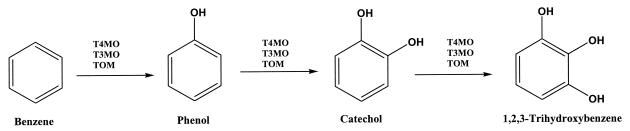

The regioselectivity of the trihydroxylation of benzene appears very restricted; since the only position for the second hydroxyl group is ortho, the third hydroxyl group is vicinal for T4MO, T3MO, and TOM. The pathway demonstrated in Fig. 2 represents a novel pathway for T4MO and T3MO for benzene oxidation in which the aromatic ring is trihydroxylated by three consecutive independent monooxygenations.

FIG. 2.

Pathway for benzene oxidation by TG1(T4MO), TG1(T3MO), and TG1(TOM).

Two goals of our laboratory have been to use toluene monooxygenases for “green chemistry” as well as to harness them for bioremediation; for example, we have successfully obtained a TOM variant, TOMGreen, with improved degradation of chlorinated compounds and improved oxidation of naphthalene to 1-naphthol (7). Hydroxylation of aromatics is an important metabolic process for bacteria, is a difficult reaction for organic chemistry, and is industrially significant for the production of pharmaceutical and agrochemical ingredients (4, 23). Our initial expectation was that DNA shuffling (31) of T4MO would yield a clone that could transform benzene to catechol. It was surprising to find that both wild-type T4MO and T3MO already make catechol and 1,2,3-THB, so it appears that the whole family of toluene monooxygenases is capable of successive hydroxylations of aromatics. Currently, in our lab T4MO, ToMO, and T3MO are being enhanced via DNA shuffling for the production of nitro-, methoxy-, and methyl-substituted catechols and to determine the residues which control regiospecificity. Application of these enzymes for producing substituted catechols would have to involve a reduction in their catechol oxidation activity, too, whereas this activity should be enhanced for the production of 1,2,3-THB.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (BES-0124401) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

We thank J. D. Stuart of the University of Connecticut for his suggestions regarding HPLC separations. We are also grateful for the assistance of A. Kind with the LC-MS analysis and acknowledge that K. A. Canada of the Wood laboratory constructed the plasmids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azerad, R. 2001. Editorial overview: better enzyme for green chemistry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:533-534. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertoni, G., F. Bolognese, E. Galli, and P. Barbieri. 1996. Cloning of the genes for and characterization of the early stages of toluene and o-xylene catabolism in Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3704-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertoni, G., M. Martino, E. Galli, and P. Barbieri. 1998. Analysis of the gene cluster encoding toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3626-3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton, S. G., A. Boshoff, W. Edwards, and P. D. Rose. 1998. Biotransformation of phenols using immobilised polyphenol oxidase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 5:411-416. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne, A. M., J. J. Kukor, and R. H. Olsen. 1995. Sequence analysis of the gene cluster encoding toluene-3-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas pickettii PKO1. Gene 154:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne, A. M., and R. H. Olsen. 1996. Cascade regulation of the toluene-3-monooxygenase operon (tbuA1UBVA2C) of Burkholderia pickettii PKO1: role of the tbuA1 promoter (PtbuA1) in the expression of its cognate activator, TbuT. J. Bacteriol. 178:6327-6337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canada, K. A., S. Iwashita, H. Shim, and T. K. Wood. 2002. Directed evolution of toluene ortho-monooxygenase for enhanced 1-naphthol synthesis and chlorinated ethene degradation. J. Bacteriol. 184:344-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan, A., S. K. Samanta, and R. K. Jain. 2000. Degradation of 4-nitrocatechol by Burkholderia cepacia: a plasmid-encoded novel pathway. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:764-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolfing, J., A. J. van den Wijngaard, and D. B. Janssen. 1993. Microbiological aspects of the removal of chlorinated hydrocarbons from air. Biodegradation 4:261-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Draths, K. M., and J. W. Frost. 1991. Conversion of D-glucose into catechol: the not-so-common pathway of aromatic biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:9361-9363. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draths, K. M., and J. W. Frost. 1995. Environmentally compatible synthesis of catechol from D-glucose. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117:2395-2400. [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Fishman, A., Y. Tao, and T. K. Wood. 2004. Toluene 3-monooxygenase of Ralstonia pickettii is a para-hydroxylating enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 186:3117-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fujita, Y., I. Mori, K. Fujita, S. Kitano, and T. Tanaka. 1985. A color reaction of 1,2-diphenols based on colored complex formation with phenylfluorone and iron (III) and its application to the assay of catecholamines in pharmaceutical preparations. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 33:5385-5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howe-Grant, M. (ed.). 1991. Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology, fourth ed., vol. 13. Wiley-Interscience Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 14.Johnson, G. R., and R. H. Olsen. 1997. Multiple pathways for toluene degradation in Burkholderia sp. strain JS150. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4047-4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadiyala, V., and J. C. Spain. 1998. A two-component monooxygenase catalyzes both the hydroxylation of p-nitrophenol and the oxidative release of nitrite from 4-nitrocatechol in Bacillus sphaericus JS905. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2479-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korte, J. E., I. Hertz-Picciotto, M. R. Schulz, L. M. Ball, and E. J. Duell. 2000. The contribution of benzene to smoking-induced leukemia. Environ. Health Perspect. 108:333-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leahy, J. G., P. J. Batchelor, and S. M. Morcomb. 2003. Evolution of the soluble diiron monooxygenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:449-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leahy, J. G., G. R. Johnson, and R. H. Olsen. 1997. Cross-regulation of toluene monooxygenases by the transcriptional activators TbmR and TbuT. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3736-3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luu, P. P., C. W. Yung, A. K. Sun, and T. K. Wood. 1995. Monitoring trichloroethylene mineralization by Pseudomonas cepacia G4 PR1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44:259-264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell, K. H., J. M. Studts, and B. G. Fox. 2002. Combined participation of hydroxylase active site residues and effector protein binding in a para to ortho modulation of toluene 4-monooxygenase regiospecificity. Biochemistry 41:3176-3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman, L. M., and L. P. Wackett. 1995. Purification and characterization of toluene 2-monooxygenase from Burkholderia cepacia G4. Biochemistry 34:14066-14076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen, R. H., J. J. Kukor, and B. Kaphammer. 1994. A novel toluene-3-monooxygenase pathway cloned from Pseudomonas pickettii PKO1. J. Bacteriol. 176:3749-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oppenheim, S. F., J. M. Studts, B. G. Fox, and J. S. Dordick. 2001. Aromatic hydroxylation catalyzed by toluene 4-monooxygenase in organic solvent/aqueous buffer mixtures. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 90:187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pikus, J. D., J. M. Studts, K. McClay, R. J. Steffan, and B. G. Fox. 1997. Changes in the regiospecificity of aromatic hydroxylation produced by active site engineering in the diiron enzyme toluene 4-monooxygenase. Biochemistry 36:9283-9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson, G. K., G. M. Stephens, H. Dalton, and P. J. Geary. 1992. The production of catechols from benzene and toluene by Pseudomonas putida in glucose fed-batch culture. Biocatalysis 6:81-100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields, M. S., S. O. Montgomery, P. J. Chapman, S. M. Cuskey, and P. H. Pritchard. 1989. Novel pathway of toluene catabolism in the trichloroethylene-degrading bacterium G4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1624-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields, M. S., M. J. Reagin, R. R. Gerger, C. Somerville, R. Schaubhut, R. Campbell, and J. Hu-Primmer. 1994. Constitutive degradation of trichloroethylene by an altered bacterium in a gas-phase bioreactor, p. 50-65. In R. E. Hinchee, A. Leeson, L. Semprini, and S. K. Ong (ed.), Bioremediation of chlorinated and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 30.Smith, M. T. 1999. Benzene, NQO1, and genetic susceptibility to cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7624-7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stemmer, W. P. C. 1994. DNA shuffling by random fragmentation and reassembly: in vitro recombination for molecular evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10747-10751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studts, J. M., K. H. Mitchell, J. D. Pikus, K. McClay, R. J. Steffan, and B. G. Fox. 2000. Optimized expression and purification of toluene 4-monooxygenase hydroxylase. Protein Expr. Purif. 20:58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Vardar, G., and T. K. Wood. 2004. Protein engineering of toluene-o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 for synthesizing 4-methylresorcinol, methylhydroquinone, and pyrogollol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3253-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Whited, G. M., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Separation and partial characterization of the enzymes of the toluene-4-monooxygenase catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. J. Bacteriol. 173:3017-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yen, K.-M., and M. R. Karl. 1992. Identification of a new gene, tomF, in the Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 174:7253-7261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yen, K.-M., M. R. Karl, L. M. Blatt, M. J. Simon, R. B. Winter, P. R. Fausset, H. S. Lu, A. A. Harcourt, and K. K. Chen. 1991. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 173:5315-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]