Abstract

SAR11 bacteria are abundant in marine environments, often accounting for 35% of total prokaryotes in the surface ocean, but little is known about their involvement in marine biogeochemical cycles. Previous studies reported that SAR11 bacteria are very small and potentially have few ribosomes, indicating that SAR11 bacteria could have low metabolic activities and could play a smaller role in the flux of dissolved organic matter than suggested by their abundance. To determine the ecological activity of SAR11 bacteria, we used a combination of microautoradiography and fluorescence in situ hybridization (Micro-FISH) to measure assimilation of 3H-amino acids and [35S]dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) by SAR11 bacteria in the coastal North Atlantic Ocean and the Sargasso Sea. We found that SAR11 bacteria were often abundant in surface waters, accounting for 25% of all prokaryotes on average. SAR11 bacteria were typically as large as, if not larger than, other prokaryotes. Additionally, more than half of SAR11 bacteria assimilated dissolved amino acids and DMSP, whereas about 40% of other prokaryotes assimilated these compounds. Due to their high abundance and activity, SAR11 bacteria were responsible for about 50% of amino acid assimilation and 30% of DMSP assimilation in surface waters. The contribution of SAR11 bacteria to amino acid assimilation was greater than would be expected based on their overall abundance, implying that SAR11 bacteria outcompete other prokaryotes for these labile compounds. These data suggest that SAR11 bacteria are highly active and play a significant role in C, N, and S cycling in the ocean.

The flux of dissolved organic matter (DOM) through marine bacterial communities is equivalent to about half of primary production (29) and thus is a crucial process in oceanic carbon cycling. It appears, though, that the phylogenetic groups comprising bacterial communities do not utilize DOM equally. Cottrell and Kirchman (4) found that α-proteobacteria preferentially assimilated dissolved free amino acids, whereas Cytophaga-like bacteria dominated the assimilation of protein in Delaware coastal waters. In the Gulf of Maine, members of the Roseobacter clade can outcompete other bacteria for dissolved dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) (17). Additionally, the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus appears to be responsible for a large fraction of dissolved methionine turnover in the Mediterranean, while another cyanobacterium, Synechococcus, does not take up significant amounts of methionine (30). The specific contribution to DOM flux by other bacterial phylogenetic groups, including some of the most abundant groups, remains unknown.

One abundant phylogenetic group is the SAR11 clade, a subgroup of the α-proteobacteria (7). Roughly a quarter of all rRNA gene sequences retrieved from marine environments belong to the SAR11 clade (22), and SAR11 bacteria often account for a large fraction (35%) of all prokaryotes in surface waters of the Sargasso Sea (18). Although SAR11 bacteria were discovered over a decade ago (6), little is known about the specific ecological role of these bacteria. Some members of the SAR11 clade have been isolated, and the genome of one species, Pelagibacter ubique, is being sequenced (22). Physiological assays of isolates and the genome sequence data will eventually provide insights into the potential metabolic activities of the SAR11 clade. To understand the ecological role of SAR11 bacteria, however, their metabolic activities under natural environmental conditions need to be investigated.

Based on their high abundance in marine environments, SAR11 bacteria potentially mediate a large fraction of DOM turnover. It has been reported, though, that SAR11 bacteria are small, about half the size of other bacteria, and have few ribosomes (18, 22); both are conditions consistent with bacterial starvation and dormancy (8, 10, 20). If the small size and low ribosome content are the result of low metabolic activity, then SAR11 bacteria may be of limited importance in oceanic DOM fluxes despite their high abundance. Additionally, the size of SAR11 bacteria may affect their mortality, since small bacteria can experience less grazing pressure than larger bacteria (9). If grazing on SAR11 bacteria is low, then low mortality, rather than fast growth, may account for their high abundance. At present, the metabolic activity of SAR11 bacteria, their contribution to DOM flux, and the specific components of the DOM pool utilized by the SAR11 bacteria are unknown.

To determine the ecological role of SAR11 bacteria, their abundance, cell volume, and assimilation of radiolabeled organic compounds were measured in the Gulf of Maine, the Sargasso Sea, and the coastal waters of North Carolina. Cell-specific assimilation of dissolved DMSP and amino acids was determined by using a combination of microautoradiography and fluorescence in situ hybridization (Micro-FISH) (4, 16, 21). Assimilation of these compounds was examined because 5 to 55% of the total bacterial C and N demand in surface waters is supplied by dissolved free amino acids (11, 27), while DMSP can satisfy 1 to 15% of C and virtually all S demand of bacterioplankton in surface waters (12, 26). We found that SAR11 bacteria were as large as other prokaryotes and often dominated the assimilation of dissolved free amino acids and DMSP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and preparation.

Seawater was collected from the surface and 10 m at 11 stations in the Gulf of Maine, the Sargasso Sea, and North Carolina coastal waters in April 2002 (Fig. 1). Thirty milliliters from 10 m was immediately fixed with fresh paraformaldehyde (2% final concentration) and stored at 4°C for 24 h before filtration onto 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters. Filtered samples were stored at −20°C for later analysis by FISH.

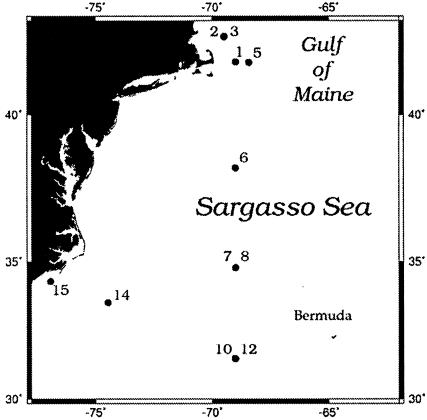

FIG. 1.

Stations sampled in the Gulf of Maine, Sargasso Sea, and North Carolina coast in April 2002. Samples were collected at 11 separate stations, although stations 2 and 3, 7 and 8, and 10 and 12 are not distinguishable at this scale.

To measure uptake of radiolabeled compounds, 30 ml of whole surface water was incubated with tracer additions of either a mixture of 15 3H-amino acids (0.5 nM; 47 Ci mmol−1; Amersham) or [35S]DMSP (<0.1 nM; 314 to 1,170 Ci mmol−1) for 24 h under in situ temperature and light conditions (minus UV). Incubations were terminated by the addition of paraformaldehyde (2% final concentration), and samples were preserved as described for FISH samples. Identical incubations with tracer additions of 35S-labeled dimethyl sulfide ([35S]DMS) were conducted to examine possible uptake of [35S]DMS produced from [35S]DMSP. Killed controls were treated with paraformaldehyde 10 min prior to addition of radiolabeled substrates and incubated simultaneously with live organisms. Assimilation of radioactive compounds was negligible in both [35S]DMS and killed-control incubations.

Enumeration of SAR11 bacteria.

The abundance of bacteria and the SAR11 clade at 10 m was determined by hybridization with fluorescent Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes (1). A suite of five general bacterial probes and a suite of four SAR11-specific probes were used to identify bacteria and SAR11 bacteria, respectively (18). Hybridization conditions followed previously described procedures (18) with some modifications. Hybridization reactions were carried out at 42°C with hybridization buffer containing 30% formamide rather than the 37°C and 20% formamide suggested previously. Hybridization temperatures and formamide concentrations were raised to increase stringency and decrease the chance of nonspecific binding, though the different hybridization conditions resulted in identical counts at the three stations where conditions were compared. Nonspecific binding was examined by hybridization with a negative control probe (5′-CCT AGT GAC GCC GTC GA-3′) (10) at a concentration of 8 ng/μl. The number of cells with nonspecific binding and autofluorescence accounted for ≤ 4% of total prokaryotes (DAPI [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole]-positive cells).

Microautoradiography.

Microautoradiography preparations followed the method described by Cottrell and Kirchman (3) with some modifications. Filter pieces were first treated with FISH to identify SAR11 bacteria collected in the surface waters. Glass slides were then coated with autoradiography emulsion by dipping them into LM-1 emulsion (Amersham Biosciences) for 35S samples and NTB-2 emulsion (Kodak) for 3H samples. FISH-treated filter pieces were placed on the emulsion-coated slides with bacteria in contact with the emulsion. Slides were chilled for 10 min to solidify the emulsion and exposed in the dark at 4°C for 2 to 6 days (3H) or 14 to 20 days (35S). After exposure, slides were developed with Dektol developer (Kodak) for 2 min, placed in a stop bath of deionized water for 10 s, fixed with Kodak fixer for 6 min, and washed in deionized water for 6 min. Slides were dried overnight in a vacuum desiccator, stained with DAPI solution (2 ng/μl) for 2 min, rinsed in 80% ethanol, dipped in 1% glycerol for 1 min, and stored overnight in a vacuum desiccator. After drying, the filter was peeled away, leaving bacteria attached to the emulsion-covered slide. Bacteria were transferred to the emulsion-covered slide with ≥ 80% efficiency. The slide was mounted with a coverslip using a 4:1 mixture of Citifluor (Ted Pella) and Vectashield (Vector Labs).

Image analysis and cell volumes.

Slides were examined with a semiautomated microscopy and image analysis system described in detail previously (3). Briefly, images of DAPI fluorescence, Cy3 fluorescence, and silver grain clusters formed during microautoradiography were acquired for each field of view, and the images were overlaid. Objects with overlapping signals in both the DAPI and Cy3 images were counted as probe positive. Silver grain clusters overlapping with DAPI-positive bacteria indicated cell-specific uptake of radiolabeled compounds. Probe-positive and substrate-assimilating cells were enumerated during image analysis, and the area of silver grains associated with cells was measured.

Cell volumes were determined from images of the DAPI fluorescence of FISH-treated samples from 10 m and calculated by using a biovolume algorithm described previously (25). These samples were not incubated with radiolabeled substrates and were not treated for microautoradiography. Cell volumes were calculated from DAPI fluorescence instead of Cy3 fluorescence so that volumes of SAR11 bacteria could be compared with the volumes other prokaryotes in the same sample. Cell volume data were log transformed for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Abundance and size of SAR11 bacteria.

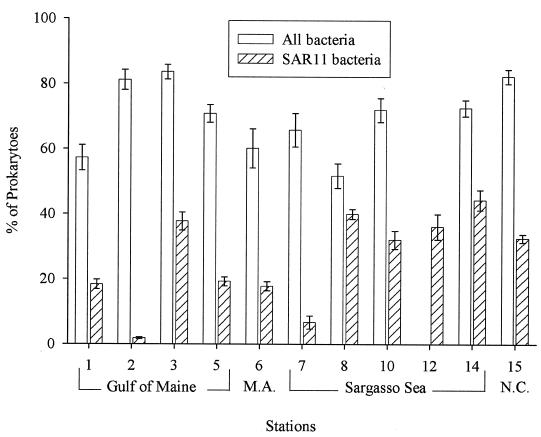

The SAR11 clade was abundant in both coastal and open ocean waters, accounting for about 25% of total prokaryote abundance, which ranged from 0.4 × 106 cells/ml in the Sargasso Sea to 1.8 × 106 cells/ml in the North Carolina coastal waters (Table 1). However, the relative abundance of SAR11 bacteria was highly variable, ranging from <2 to 40% of total prokaryotes in the Gulf of Maine (Fig. 2). Members of the SAR11 clade comprised an even larger fraction, 37% on average, of total bacteria identified by hybridization with general bacterial probes.

TABLE 1.

Total prokaryote abundance and average cell volumes of SAR11 bacteria and other prokaryotes in the Gulf of Maine, the Sargasso Sea, and North Carolina coastal waters

| Location | Station | Abundance (106 cells ml−1)a | Cell vol (μm3)b

|

% CVc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAR11 | Other prokaryotes | ||||

| Gulf of Maine | 1 | 4.0 ± 0.70 | 0.034 ± 0.004 | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 64 |

| Gulf of Maine | 3 | 1.0 ± 0.25 | 0.031 ± 0.001 | 0.033 ± 0.001* | 49 |

| Gulf of Maine | 5 | 1.1 ± 0.33 | 0.045 ± 0.002 | 0.045 ± 0.001 | 53 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 6 | 1.0 ± 0.31 | 0.048 ± 0.004 | 0.040 ± 0.002* | 57 |

| Sargasso Sea | 7 | 1.4 ± 0.48 | 0.041 ± 0.002 | 0.037 ± 0.001* | 59 |

| Sargasso Sea | 8 | 0.9 ± 0.36 | 0.051 ± 0.002 | 0.040 ± 0.002* | 48 |

| Sargasso Sea | 10 | 0.4 ± 0.24 | 0.050 ± 0.003 | 0.043 ± 0.003* | 46 |

| Sargasso Sea | 12 | 0.5 ± .010 | 0.044 ± 0.003 | 0.039 ± 0.003* | 35 |

| Sargasso Sea | 14 | 1.0 ± 0.25 | 0.048 ± 0.003 | 0.036 ± 0.003* | 44 |

| North Carolina coastal waters | 15 | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 0.043 ± 0.002 | 0.034 ± 0.002* | 39 |

Means ± standard deviations for 10 fields of view.

Means ± 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant differences (t test; P < 0.01) between the cell sizes of SAR11 bacteria (n = 132 to 629) and other prokaryotes (n = 257 to 2,273) are indicated (*). Cell volumes were determined from FISH samples at 10 m and did not undergo microautoradiography preparation.

Coefficient of variation of SAR11 cell volume.

FIG. 2.

Abundance of bacteria and SAR11 bacteria at 10 m in the Gulf of Maine, mid-Atlantic (M.A.), Sargasso Sea, and North Carolina (N.C.) coastal waters. The abundance of bacteria detected by general bacterial probes (open bars) and SAR11 bacteria (filled bars) is expressed as a percentage of total prokaryotes (DAPI-positive cells). Error bars represent the standard errors of 30 fields of view. These data are from FISH analyses, not the microautoradiography preparations.

The average cell volumes of SAR11 bacteria ranged from 0.031 to 0.051 μm3 (Table 1) and were typically as large as those of other prokaryotes in the same community. In the Sargasso Sea, members of the SAR11 clade were larger (13 to 33%) than other prokaryotes. The SAR11 bacteria in coastal waters of the Gulf of Maine were the same size as other prokaryotes at two of three stations, while SAR11 bacteria off the coast of North Carolina were 26% larger than other prokaryotes (Table 1). In addition, the SAR11 bacteria in the Sargasso Sea were also typically bigger (22% on average) than SAR11 bacteria found in coastal waters (nested analysis of variance; P < 0.05).

DMSP and amino acid assimilation.

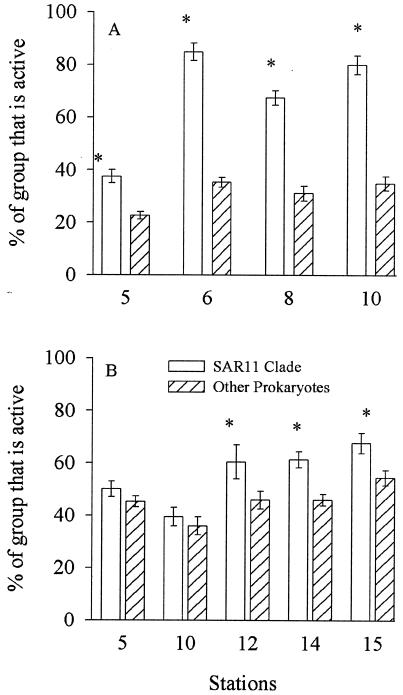

Over half of the SAR11 bacteria assimilated dissolved DMSP or amino acids (Fig. 3). The fraction of active SAR11 bacteria was equal to or greater than the active fraction of the other prokaryotes. The fraction of SAR11 bacteria assimilating amino acids was particularly high (67 to 85%) in the open ocean, while only 31 to 35% of other prokaryotes assimilated amino acids (Fig. 3A). The portion of the SAR11 clade assimilating DMSP was also high in the Sargasso Sea (40 to 60%) compared to that of other prokaryotes (36 to 46%) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Percentage of SAR11 bacteria and all other prokaryotes assimilating dissolved free amino acids (A) and dissolved DMSP (B) in the Gulf of Maine, the Sargasso Sea, and North Carolina coastal waters. Statistically significant differences (t test; P < 0.05) between SAR11 bacteria and other prokaryotes are indicated (*). Error bars represent the standard errors of 30 fields of view.

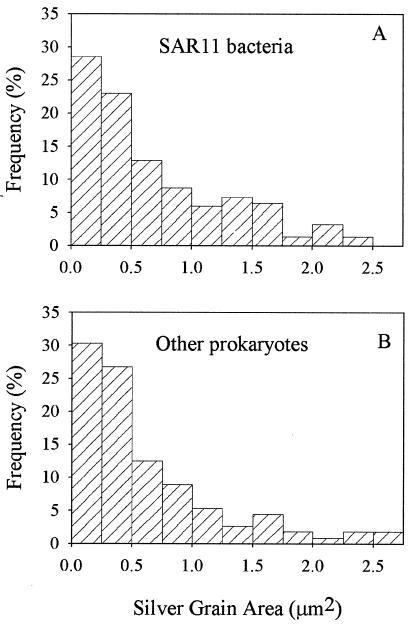

Variation in cell-specific activity was examined by using the size (in square micrometers) of silver grain clusters associated with SAR11 bacteria assimilating amino acids. Bacteria with large silver grain areas were assumed to be more active than cells with small silver grain areas (3, 19). The area of silver grain clusters varied greatly at all stations (coefficient of variation, 84 to 100%), suggesting large variations in the single-cell activity of SAR11 bacteria and other prokaryotes. Cell-specific activity was not distributed normally. Most active SAR11 bacteria had small silver grain clusters, while a few had very large silver grain clusters (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that a small fraction of the SAR11 clade was much more active metabolically than other active SAR11 bacteria. The distribution of per-cell activity of other bacteria was similar to the distribution of SAR11 bacteria (Fig. 4B). Distributions of cell-specific activity were similar at all stations (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Frequency distribution of silver grain cluster areas associated with SAR11 bacteria (A) and all other prokaryotes (B) assimilating amino acids at station 8 in the Sargasso Sea. Silver grain areas were grouped into bins at 0.25-μm2 increments. These distributions are representative of those from all other stations where amino acid assimilation was measured.

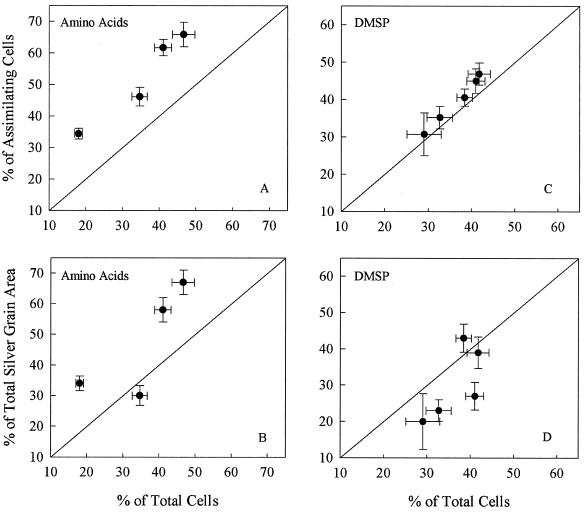

When abundant, members of the SAR11 clade appear to be responsible for a substantial fraction of DOM assimilation. SAR11 bacteria accounted for 34 to 66% of cells assimilating dissolved free amino acids in surface waters (Fig. 5A). The contribution of the SAR11 clade to the amino acid-assimilating community was greater than expected based upon their overall abundance. For example, the SAR11 clade made up 41% of total prokaryotes at station 10 in the Sargasso Sea, yet they accounted for 62% of cells assimilating amino acids (Fig. 5A). Since cell-specific assimilation varied, we also used the fraction of total silver grain area associated with SAR11 bacteria to estimate assimilation. Based on silver grain area, SAR11 bacteria dominated the assimilation of dissolved free amino acids, though at one coastal station they did not assimilate more amino acids than expected based on their abundance (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Contribution of SAR11 bacteria to the assimilation of dissolved free amino acids and DMSP. Abundance of SAR11 bacteria in the amino acid- and DMSP-assimilating community is plotted against abundance of SAR11 bacteria in the total prokaryote community (A and C). Percentage of total silver grain area associated with SAR11 bacteria is plotted against the abundance of SAR11 bacteria in the total prokaryote community (B and D). Error bars represent the standard errors of 30 fields of view.

SAR11 bacteria also dominated the assimilation of dissolved DMSP, accounting for 31 to 47% of the DMSP-assimilating community (Fig. 5C). The contribution of SAR11 bacteria to the DMSP-assimilating community was about that expected based on their overall abundance, though SAR11 bacteria did comprise a greater fraction of the DMSP-assimilating community at one station in the Sargasso Sea. The silver grain area associated with SAR11 bacteria also suggests that these bacteria were responsible for 20 to 43% of dissolved DMSP assimilation at various stations (Fig. 5D). However, at four of five stations the fraction of total DMSP assimilation mediated by SAR11 bacteria, as measured by silver grain area, was less than expected based on their overall abundance.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria of the SAR11 clade often dominate the marine microbial communities in both the surface and deep waters of the ocean, making them one of them of the most abundant organisms on the planet (18). Due to their high abundance, SAR11 bacteria potentially mediate a large portion of the DOM flux. However, the activity of SAR11 bacteria cannot be deduced solely from their abundance. Bacteria with moderate or even low levels of activity could become abundant if their mortality is low due to a resistance to grazing or viral infection, while the abundance of highly active bacteria could be constrained by grazing or lysis (9). Indeed, large and actively dividing bacteria are preferentially removed by micrograzers, while very small bacteria experience less grazing pressure (24). Previous studies reported that SAR11 bacteria are very small and have few ribosomes (18, 22), conditions that are consistent with low levels of metabolic activity and grazing pressure. These data suggest that SAR11 bacteria may become abundant due in part to low mortality and contribute less to DOM flux than would be expected based on their high abundance. We found that SAR11 bacteria, instead of being small and starving, typically had high metabolic activities and were not small compared to other prokaryotes. Because of their activity and abundance, which was often high, the SAR11 clade frequently dominated the flux of dissolved DMSP and amino acids.

SAR11 bacteria in culture were previously (22) found to be three- to fivefold smaller than SAR11 bacteria in this study, and Morris et al. (18) reported that uncultured members of the SAR11 clade were about half the size of other bacteria in the Sargasso Sea, in contrast to our results. The differences in the size of SAR11 bacteria could result from the different methods used to measure cell size, i.e., transmission electron microscopy (22) versus image analysis of Cy3 fluorescence (18) and DAPI fluorescence (this study). Alternatively, the size of SAR11 bacteria may vary temporally and geographically. In fact, the average cell volume of SAR11 bacteria varied substantially among sites in the Gulf of Maine and Sargasso Sea (Table 1). Large variability in cell size within sites is indicated by the high coefficients of variation (35 to 64%) (Table 1). It is also possible that the SAR11 bacteria observed in this study were not the same as those observed previously. The SAR11 clade is diverse, with 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities as low as 0.87 (23). Differences in cell size may be a result of this diversity. Regardless of differences in absolute cell size, the SAR11 bacteria were not smaller than the other prokaryotes at nine of the ten sites examined in the North Atlantic. Since cell size is often positively correlated with metabolic activity (15, 17), these data suggest that SAR11 bacteria are as active as other marine bacteria.

A more direct measure of metabolic activity is the assimilation of radiolabeled organic compounds. Assimilation into macromolecules, rather than total uptake, is monitored by Micro-FISH because cells fixed with paraformaldehyde lose unincorporated radioactive compounds (13, 17). Using Micro-FISH, we found that roughly half of the SAR11 bacteria assimilated dissolved free amino acids and DMSP. The percentage of other prokaryotes assimilating amino acids and DMSP was typically smaller than the percentage of SAR11 bacteria assimilating these compounds. The difference between the active fraction of SAR11 bacteria and other bacteria was greatest in the Sargasso Sea, indicating that SAR11 bacteria may be particularly well adapted to the oligotrophic conditions of the open ocean. Cell volume data are consistent with this hypothesis, since SAR11 bacteria from the Sargasso Sea were both larger than other prokaryotes in the Sargasso Sea and larger than the SAR11 bacteria found in coastal waters.

The success of SAR11 bacteria may be partially attributable to their ability to dominate the assimilation of particular components of the DOM pool. Members of the SAR11 clade assimilated a disproportionately large amount of dissolved free amino acids compared to the rest of the microbial community. SAR11 bacteria may assimilate dissolved free amino acids preferentially and outcompete other bacteria for these substrates. This hypothesis is consistent with previous observations of preferential amino acid assimilation by α-proteobacteria (4). Dominance in the assimilation of dissolved free amino acids, which can supply substantial amounts of C and N to microbial communities (11, 27), could convey a competitive advantage to SAR11 bacteria because microbial communities are often limited by C or N (5, 14).

Since dissolved amino acids supply 5 to 55% of the total bacterial C and N demand (11, 27), and DMSP can supply 1 to 15% of the C and nearly all of the S demand in surface waters (12, 26), assimilation of DMSP and amino acids by SAR11 bacteria should satisfy a substantial fraction of their C, N, and S needs. Assimilation, however, is not the only metabolic fate for DMSP and amino acids. Depending upon their assimilation efficiency, SAR11 bacteria probably respire a considerable amount of DMSP and amino acids, a process that was not measured in this study. Estimates of the respiration of dissolved DMSP are unavailable, but the efficiency for total dissolved free amino acid assimilation is generally less than 50% (27). If SAR11 bacteria assimilate amino acids with less than 50% efficiency, then the respiration of amino acids may be a significant energy source for SAR11 bacteria. Since the assimilation and respiration of dissolved DMSP and amino acids probably support a substantial portion of the biosynthetic and energetic needs of SAR11 bacteria, the metabolism of these compounds likely accounts for much of the total DOM flux mediated by SAR11 bacteria.

Previously, Malmstrom et al. (17) reported that α-proteobacteria dominated the assimilation of DMSP in both coastal waters (station 5) and the Sargasso Sea (stations 12 to 14). In coastal waters, about half of the assimilation attributed to α-proteobacteria, as determined by silver grain area, was accounted for by members of the Roseobacter clade, a subgroup of the α-proteobacteria (7). The Roseobacter clade assimilated far more DMSP than predicted by their abundance, but the clade was not found in the Sargasso Sea. Other α-proteobacteria filled the niche of the Roseobacter clade in the Sargasso Sea, though it was unclear which α-proteobacteria took over. In this study, we found that SAR11 bacteria could account for the other half of DMSP assimilated by α-proteobacteria at station 5 (coastal waters) and 43 to 71% of the assimilation by α-proteobacteria at stations 12 and 14 (Sargasso Sea). These data suggest that SAR11 bacteria are important consumers of dissolved DMSP, especially in the open ocean.

The assimilation of dissolved DMSP by SAR11 bacteria could have a significant impact on oceanic S cycling and global climate. DMSP is the biogenic precursor of DMS, a volatile organic sulfur compound produced from DMSP hydrolysis and emitted into the atmosphere (28). Emissions of DMS are hypothesized to mitigate greenhouse warming by increasing the Earth's cloud cover and albedo (2). The assimilation of DMSP could, however, reduce DMS emissions by consuming the precursor of DMS. When averaged across all environments, SAR11 bacteria were responsible for about 33% of dissolved DMSP assimilation, indicating that the assimilation of DMSP by the SAR11 clade could reduce DMS emissions from the ocean.

If the assimilation of dissolved DMSP and amino acids is any indication, then bacteria of the SAR11 clade are likely to play an important role in the flux of DOM through marine microbial food webs. The flux of DOM mediated by microbial communities is about 50% of oceanic primary production (29). Assuming that the fraction of total DOM uptake by SAR11 bacteria is comparable to their assimilation of DMSP and amino acids (ca. 30 and 47% of total incorporation, respectively), SAR11 bacteria may, when abundant, process roughly 15 to 25% of C fixed in the surface waters of the ocean. Based on the abundance, high metabolic activity, and cosmopolitan distribution of the SAR11 clade (18), SAR11 bacteria are likely to influence biogeochemical cycling of C, N, and S on a global scale.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from DOE-BIOMP (DF-FG02-97 ER 62479) and NSF (OCE-9908808). A National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship provided support for R.R.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlson, R. J., J. E. Lovelock, M. O. Andreae, and S. G. Warren. 1987. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulfur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature 326:655-661. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cottrell, M. T., and D. L. Kirchman. 2003. Contribution of major bacterial groups to bacterial biomass production (thymidine and leucine incorporation) in the Delaware estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48:168-178. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottrell, M. T., and D. L. Kirchman. 2000. Natural assemblages of marine proteobacteria and members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacter cluster consuming low- and high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1692-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elser, J. J., L. B. Stabler, and R. P. Hassett. 1995. Nutrient limitation of bacterial growth and rates of bacterivory in lakes and oceans—a comparative study. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 9:105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannoni, S. J., T. B. Britschgi, C. L. Moyer, and K. G. Field. 1990. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature 345:60-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannoni, S. J., and M. S. Rappé. 2000. Evolution, diversity, and molecular ecology of marine prokaryotes, p. 47-84. In D. L. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the oceans. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 8.Hood, M. A., J. B. Guckert, D. C. White, and F. Deck. 1986. Effect of nutrient deprivation on lipid, carbohydrate, DNA, RNA, and protein-levels in Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:788-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jürgens, K., and C. Matz. 2002. Predation as a shaping force for the phenotypic and genotypic composition of planktonic bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 81:413-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karner, M., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1997. Determination of active marine bacterioplankton: a comparison of universal 16S rRNA probes, autoradiography, and nucleoid staining. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1208-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keil, R. G., and D. L. Kirchman. 1991. Contribution of dissolved free amino acids and ammonium to the nitrogen requirements of heterotrophic bacterioplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 73:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiene, R. P., and L. J. Linn. 2000. Distribution and turnover of dissolved DMSP and its relationship with bacterial production and dimethylsulfide in the Gulf of Mexico. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:849-861. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiene, R. P., and L. J. Linn. 1999. Filter-type and sample handling affect determination of organic substrate uptake by bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 17:311-321. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchman, D. L., and J. H. Rich. 1997. Regulation of bacterial growth rates by dissolved organic carbon and temperature in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Microb. Ecol. 33:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebaron, P., P. Servais, A. C. Baudoux, M. Bourrain, C. Courties, and N. Parthuisot. 2002. Variations of bacterial-specific activity with cell size and nucleic acid content assessed by flow cytometry. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 28:131-140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, N., P. H. Nielsen, K. H. Andreasen, S. Juretschko, J. L. Nielsen, K. H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. Combination of fluorescent in situ hybridization and microautoradiography—a new tool for structure-function analyses in microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1289-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malmstrom, R. R., R. P. Kiene, and D. L. Kirchman. 2004. Identification and enumeration of bacteria assimilating dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in the North Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49:597-606. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris, R. M., M. S. Rappé, S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, W. A. Siebold, C. A. Carlson, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. SAR11 clade dominates ocean surface bacterioplankton communities. Nature 420:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen, J. L., D. Christensen, M. Kloppenborg, and P. H. Nielsen. 2003. Quantification of cell-specific substrate uptake by probe-defined bacteria under in situ conditions by microautoradiography and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Environ. Microbiol. 5:202-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novitsky, J. A., and R. Y. Morita. 1976. Morphological characterization of small cells resulting from nutrient starvation of a psychrophilic marine Vibrio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:617-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouverney, C. C., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1999. Combined microautoradiography-16S rRNA probe technique for determination of radioisotope uptake by specific microbial cell types in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1746-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappé, M. S., S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 418:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rappé, M. S., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2003. The uncultured microbial majority. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:369-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherr, B. F., E. B. Sherr, and J. McDaniel. 1992. Effect of protistan grazing on the frequency of dividing cells in bacterioplankton assemblages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2381-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieracki, M. E., C. L. Viles, and K. L. Webb. 1989. Algorithm to estimate cell biovolume using image analyzed microscopy. Cytometry 10:551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simó, R., S. D. Archer, C. Pedrós-Alió, L. Gilpin, and C. E. Stelfox-Widdicombe. 2002. Coupled dynamics of dimethylsulfoniopropionate and dimethylsulfide cycling and the microbial food web in surface waters of the North Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:53-61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suttle, C. A., A. M. Chan, and J. A. Fuhrman. 1991. Dissolved free amino acids in the Sargasso Sea—uptake and respiration rates, turnover times, and concentrations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 70:189-199. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner, S. M., G. Malin, P. S. Liss, D. S. Harbour, and P. M. Holligan. 1988. The seasonal variation of dimethyl sulfide and dimethylsulfoniopropionate concentrations in nearshore waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:364-375. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams, P. J. L. B. 2000. Heterotrophic bacteria and the dynamics of dissolved organic matter, p. 153-200. In D. L. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the oceans. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 30.Zubkov, M. V., B. M. Fuchs, G. A. Tarran, P. H. Burkill, and R. Amann. 2003. High rate of uptake of organic nitrogen compounds by Prochlorococcus cyanobacteria as a key to their dominance in oligotrophic oceanic waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1299-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]