Abstract

Achieving universal primary education is one of the Millennium Development Goals. In low- and middle-income developing countries (LMIC), child labor may be a barrier. Few multi-country, controlled studies of the relations between different kinds of child labor and schooling are available. This study employs 186,795 families with 7- to 14-year-old children in 30 LMIC to explore relations of children’s work outside the home, family work, and household chores with school enrollment. Significant negative relations emerged between each form of child labor and school enrollment, but relations were more consistent for family work and household chores than work outside the home. All relations were moderated by country and sometimes by gender. These differentiated findings have nuanced policy implications.

Keywords: Child labor, school enrollment, LMIC

Children in impoverished households in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) may contribute to their family’s welfare by working outside the home or for the family or by managing household responsibilities while parents work. UNICEF (2007) estimated that 1 in 6 children aged 5–14 was involved in some sort of child labor. However, the prevalence of child labor is difficult to extimate because of inconsistent definitions of child labor. Some definitions of child labor include only paid work outside the home (i.e., economic or market work), whereas other definitions include unpaid work, family work, and excessive household chores because each form of work may relate to child schooling, health, and well-being (ILO, 2009). By contrast with its contribution to the family, engaging in child labor is widely believed to have a strong negative impact on schooling (Bezerra, Kassouf, & Arends-Kuening, 2009; Orazem & Gunnarsson, 2003; Ray & Lancaster, 2005) but some research reports little or no relation (No, Sam, & Hirakawa, 2012; Ravaillion & Wodon, 2000). We hope to resolve this ambiguity by exploring relations of different types of child labor with school enrollment in a diverse set of 30 LMIC.

Three Types of Child Labor

Child labor is often divided into three major categories: work outside the home, family work, and excessive household chores. Children’s work outside the home has received the most empirical attention. Work outside the home usually consists of employment in agriculture, services, or industry and can be paid or unpaid. Family work consists of any (usually unpaid) work that children do for the family. Family work is most often agricultural (e.g., subsistence farming; Edmonds & Pavcnik, 2005), but it also includes work for other family-owned businesses. Finally, household chores include childcare, cleaning, cooking, laundry, shopping, fetching water and wood, and home maintenance. Most children engage in household chores as part of their play routines and as a means of socialization to their culture (Lancy, 2012). Excessive household chores (herein defined as ≥ 28 hours per week; UNICEF, 2006) are considered a “hidden” form of child labor because they may interfere with schooling, are unpaid, and often go unreported (Gibbons, Huebler, & Loaiza, 2005).

Child Labor and Poverty

Child labor is more common in so called “developing” countries than developed countries (Fares & Raju, 2007). The countries included in this study all constitute low- and middle-income developing countries (UNICEF, 2006). Although there is considerable variation within individual countries, children and caregivers in LMIC are likely to have a low standard of living (World Bank, 2012) and few material resources (Bradley & Putnick, 2012), and they are unlikely to have access to governmentally sponsored social assistance programs (World Bank, 2012). The ILO (2006) estimated that over 70% of child labor is agricultural; in most cases, children in LMIC work for their family’s farm (Edmonds & Pavcnik, 2005). Thus, children in LMIC may engage in child labor because their families need them to work to survive. Galli (2001) suggested that paid child labor contributed 10 to 20% of family income, depending on the location. If indirect contributions of unpaid family work (e.g., family farm or business work) and household chores (e.g., childcare) are considered, a 10 to 20% contribution to family income may be a substantial underestimate.

Child Labor and Education

One of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDG 2) is to achieve universal primary education by 2015 (United Nations, 2013). Most countries have made strides toward this goal by improving access to schools. Primary school enrollment rates have improved steadily in most countries since the year 2000 (World Bank, 2014). However, some countries, especially the lowest income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, are far from reaching the goal of universal education (United Nations, 2013). Some scholars implicate child labor as a barrier to achieving universal education because poor families need children to work, which prevents them from attending school. Just as school enrollment has increased, engagement in child labor has decreased globally (Diallo, Hagemann, Etienne, Gurbuzer, & Mehran, 2010). Nonetheless, the empirical link between child labor and schooling has so far been incompletely documented. The ambiguity about the association between child labor and schooling stems from at least four issues: (1) most efforts to demonstrate the association between child labor and schooling involve only a single country or a single region within a country, (2) studies vary in their inclusion of different types of child labor, (3) studies vary in their operationalization of labor (e.g., how many hours of work constitute labor), and (4) studies vary in the indicators of education (e.g., enrollment vs. attendance vs. school performance). In this investigation, we included 30 LMIC, 3 types of child labor in addition to a global index, defined child labor according to UNICEF’s (2006) standard guidelines, and focused on school enrollment exclusively.

If children are working, are they less likely to be enrolled in school? The two activities are not necessarily mutually exclusive; the majority of working children continue to be enrolled in school. Some studies of individual countries report that children who work are less likely to be enrolled in school (Amin, Quayes, & Rives, 2006; Beegle, Dehejia, & Gatti, 2009; Fares & Raju, 2007; Gibbons et al., 2005; Guarcello, Lyon, & Rosati, 2008; Huebler, 2008), but others find little to no relation between child labor and enrollment (No et al., 2012; Ravallion & Wodon, 2000). In one of only a few systematic studies that included multiple countries, Gibbons et al. (2005) investigated 18 African countries and found negative relations between a composite indicator of child labor and school enrollment in 10 countries, a positive relation in 1 country, and no relation in 7 countries. Similarly, Guarcello et al. (2008) reported that economically active 7- to 14-year-old children had lower school attendance rates than non-economically active children in 48 of 60 developing countries, higher attendance rates than non-economically active children 7 countries, and essentially equivalent rates in 5 countries. These studies underscore how child labor might serve different functions in different countries (Morrow, 2010).

The effects of different types of child labor on education are also unclear. Goulart and Bedi (2008) assessed economic work inside or outside the household and household domestic work in 6- to 15-year-old children. Economic work had a significant negative relation with school success (i.e., not repeating a grade), but domestic work was unrelated to school success. Guarcello et al. (2008) reported that hours of economic work, as well as household chores, were related to the probability of attending school in Bolivia, Cambodia, Mali, and Senegal (see also Beegle et al., 2009, for Vietnam). Finally, in a study of 16 countries, Allais (2009) reported that engaging in 28 or more hours of economic work was associated with over 30% lower school enrollment relative to working fewer than 14 hours, and 28 or more hours of household chores was associated with nearly 20% lower school enrollment for girls and 10% lower enrollment for boys relative to working fewer than 14 hours. Unpaid family work, the most common type of child labor in the developing world (Putnick & Bornstein, in press), has rarely been studied. Given the ambiguity in the literature on relations between different types of child labor and education, here we disaggregate the three types of child labor in relation to school enrollment.

Factors Affecting the Link Between Child Labor and Schooling

Some family and personal variables may confound relations between child labor and education. For example, the link between caregiver education and child school enrollment is well documented. Children with educated primary caregivers (especially mothers) are more likely to be enrolled in school (Gibbons et al., 2005; Huebler, 2008; Kurosaki, Ito, Fuwa, Kubo, & Sawada, 2006) and are less likely to participate in child labor (Huebler, 2008; Kurosaki et al., 2006). Child age may also relate to both child labor and schooling. Older children may be more likely to drop out of school as well as engage in child labor (Rosati & Rossi, 2003). To account for variation in these factors, caregiver education and child age were controlled in analyses.

Some family and personal variables may also moderate relations between child labor and education. As previously described, relations between child labor and education may not be consistent across countries (Gibbons et al., 2005; Guarcello et al., 2008). Child gender is another factor that likely moderates the association between child labor and education. Putnick and Bornstein (in press) documented gender differences in patterns of child labor across 38 developing countries, and several researchers have reported differences in rates of school enrollment for girls and boys (Beegle at al., 2009; Gibbons et al., 2005; Huebler, 2008). Whether the relations between child labor and education are similar for girls and boys remains an open question. Consequently, we explore the relations of child labor with education by country and by gender to determine whether these factors moderate the effects of child labor on school enrollment.

This Study

This study explores relations of child labor with school enrollment in more than 185,000 7- to 14-year-old children in 30 LMIC. In addition to employing a composite index of all types of child labor, we explore work outside the home, family work, and excessive household chores separately to determine whether each type of labor has similar relations with schooling. We control for child age and caregiver education and also examine potential moderating effects of country and child gender.

Method

Participants

We evaluate child labor and education in girls and boys in 186,795 families in 30 LMIC (Table 1). Countries had available data and scored below the .80 cutoff (i.e., low or medium) on the Human Development Index (HDI; UNDP, 2008); this score reflects the country’s level of social and economic development. In this investigation, we limited the age range to children between 7 and 14 because formal schooling does not begin until age 7 in some countries. We randomly selected a child from each family. Children averaged 10.34 years of age (SD = 2.31, range = 7–14), and 49.8% were female.

Table 1.

Percentages of children who engaged in any kind of child labor and schooling by country, odds ratios, predicted probabilities, and difference in predicted probabilities for the main effect of child labor predicting school enrollment

| Country | n | no labor, no school | no labor, school | labor, no school | labor, school | child labor OR | Predict. Prob.b | Diff. prob.c. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 36162 | 10.0 | 74.8 | 6.4 | 8.7 | .22*** | .53 | −.43 |

| Burundi | 4875 | 16.0 | 63.7 | 8.2 | 12.1 | .38*** | .54 | −.35 |

| Cameroon | 4792 | 9.3 | 54.5 | 6.0 | 30.1 | 1.00 | .85 | .00 |

| Central African Republic | 5489 | 18.6 | 30.6 | 22.2 | 28.6 | .90 | .57 | −.05 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 5923 | 19.5 | 39.4 | 20.3 | 20.8 | .58*** | .47 | −.26 |

| Djibouti | 2447 | 21.4 | 71.8 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 1.15 | .80 | .05 |

| Gambia | 5261 | 18.8 | 52.8 | 9.8 | 18.7 | 1.21** | .75 | .08 |

| Georgia | 3262 | 1.0 | 80.0 | 0.2 | 18.8 | -- | -- | -- |

| Ghana | 3158 | 7.8 | 52.8 | 9.7 | 29.6 | .60*** | .74 | −.15 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 4507 | 17.6 | 41.0 | 14.7 | 26.7 | 1.04 | .69 | .02 |

| Guyana | 2476 | 2.7 | 77.3 | 0.8 | 19.2 | .68 | .95 | −.03 |

| Iraq | 10510 | 14.5 | 75.0 | 3.5 | 7.0 | .39*** | .64 | −.28 |

| Jamaica | 1746 | 0.5 | 93.8 | 0.1 | 5.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2652 | 2.8 | 94.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | -- | -- | -- |

| Laos | 3965 | 16.8 | 69.9 | 3.9 | 9.5 | .62*** | .70 | −.16 |

| Mauritania | 6413 | 18.7 | 63.7 | 5.8 | 11.7 | .71*** | .68 | −.13 |

| Mongolia | 3086 | 2.9 | 77.6 | 1.2 | 18.3 | .61* | .94 | −.04 |

| Mozambique | 8095 | 12.1 | 63.2 | 4.4 | 20.3 | .93 | .83 | −.02 |

| Nigeria | 15094 | 24.5 | 44.5 | 11.2 | 19.8 | 1.15*** | .67 | .06 |

| Sierra Leone | 4714 | 10.8 | 41.6 | 14.7 | 32.9 | .64*** | .65 | −.17 |

| Somalia | 3458 | 14.4 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 28.0 | .51*** | .40 | −.32 |

| Suriname | 2227 | 3.6 | 91.9 | 0.9 | 3.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| Syria | 10252 | 7.2 | 88.5 | 1.9 | 2.5 | .15*** | .60 | −.38 |

| Tajikistan | 4472 | 6.6 | 80.4 | 0.8 | 12.3 | 1.00 | .93 | .00 |

| Thailand | 14257 | 1.1 | 89.1 | 0.5 | 9.3 | .25*** | .94 | −.06 |

| Togo | 3990 | 15.1 | 52.4 | 10.2 | 22.3 | .68*** | .67 | −.15 |

| Ukraine | 1424 | 0.4 | 88.8 | 0.1 | 10.7 | -- | -- | -- |

| Uzbekistan | 5562 | 2.2 | 94.7 | 0.1 | 3.1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Vietnam | 3970 | 2.6 | 77.6 | 2.7 | 17.1 | .37*** | .87 | −.11 |

| Yemen | 2556 | 18.4 | 54.5 | 9.4 | 17.7 | .61*** | .61 | −.20 |

|

| ||||||||

| TOTAL | 186795 | 12.4 | 65.2 | 7.5 | 15.0 | .55***a | .69a | −.19 a |

Note. OR = Odds Ratio.

-- = Statistics were not computed because there were <5 cases expected in more than one cell in the contingency table between labor and school enrollment by gender (Rosner, 1995).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Excluding countries with no statistics above.

Predicted probability of being enrolled in school if engaging in child labor, controlling for child gender and age, and caregiver education.

Difference in the predicted probabilities of being enrolled in school if not engaging in child labor and if engaging in child labor, controlling for child gender and age, and caregiver education.

Questions about labor and education were answered by the child’s primary female caregiver, who was usually the child’s natural mother (87.0%); of the 13.0% of questionnaires that were completed by someone other than the child’s natural mother, 98.2% had no natural mother living in the household. The child’s primary female caregiver averaged 38.16 years (SD = 10.14, range = 15–97), and the highest level of education completed was none or preschool for 39.5% of caregivers, primary school/non-standard curriculum/religious school for 30.7% of caregivers, secondary/vocational/tertiary school for 25.6% of caregivers, and higher for 4.3% of caregivers. Sample demographics by country are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Procedures

MICS3

Data for this study were drawn from the third round of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (UNICEF, 2006). The MICS3 is a nationally representative and internationally comparable household survey that was carried out in 50 LMIC between 2005 and 2010, some of which did not include questions about child labor or did not make data publicly available. Hence the number of countries with available data was 38. We then excluded 8 high-HDI countries with available data from this investigation because fewer than 5% of children in these countries were engaged in child labor and fewer than 0.5% were working and not enrolled in school. The 30 countries we include represent 5 countries in central and eastern Europe, 5 countries in eastern Asia and the Pacific, 13 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 4 countries in the Middle East and northern Africa, and 3 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Child labor

Questions about child labor were drawn from the child labor module in the MICS3 Household Questionnaire. The primary caregiver of each child between 7 and 14 years indicated whether the child had worked outside the home, engaged in family work (like a family farm or business), or helped with household chores (like shopping, collecting firewood, fetching water, and childcare) in the past week (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Caregivers also estimated the number of hours the child had worked outside the home, engaged in family work, and done household chores in the past week.

Following UNICEF (2006) guidelines, we computed a child labor index combining work outside the home, family work, and excessive household chores into a single indicator. Children aged 7 to 11 were considered to engage in child labor if they had worked for 1 hour or more (outside the family or for the family) and/or 28 or more hours of household chores during the preceding week. Children aged 12 to 14 were considered to engage in child labor if they had worked for 14 or more hours (outside the family or for the family) and/or 28 or more hours of household chores during the preceding week. In addition to the child labor index, we explored the three components (work outside the home, family work, and excessive household chores) separately because these three types of child labor may have different relations with education and the prevalences differ for girls and boys (Putnick & Bornstein, in press).

Allowing older children to work up to 2 hours per day without being counted as child labor accounts for the potential benefits associated with small amounts of work in this age group (Larson & Verma, 1999). The age group employed in the current sample and the definitions of child labor employed (i.e., excluding <14 hours of work in preteens, and reasonable hours of household chores for all ages) circumscribes our investigation to child labor that is likely to interfere with healthy child development.

Education

As part of the MICS3 Education module of the Household questionnaire, the child’s primary caregiver indicated whether the child had attended school at any time during the current academic year.

Analytic Plan

First, we explored the proportion of children who were engaged in child labor in relation to the proportion of children who were enrolled in school at the country level using phi coefficients (φ) for correlations between two dichotomous variables. Next, we performed logistic regression analyses to investigate whether child labor and educational enrollment were related at the family level and whether these relations were moderated by child gender and country when controlling for child age and caregiver education. Countries were excluded that had expected cell counts under 5 for more than one cell in the contingency table of labor by education by gender (Rosner, 1995). In these excluded countries, the smallest cells were almost always those of girls and boys who were engaged in child labor and were not enrolled in school. Six countries (Georgia, Jamaica, Kyrgyzstan, Suriname, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan) were excluded from all analyses (except preliminary analyses at the country level) because of low cell counts. In these six countries, very small numbers of children engaged in child labor without also being enrolled school.

In logistic regression analyses, we used child labor as a predictor of school enrollment. We included the main effects of country and gender so that interactions with child labor could be interpreted, and we included interactions between gender and country so that the 3-way interaction of country, gender, and child labor could be interpreted. However, to focus this report on labor and education we only report the main effect of child labor and any interactions with child labor. We report the odds ratio (OR) as an indication of effect size, which can be interpreted in terms of the odds of occurrence. For example, an OR of 2.0 for the main effect of child labor means that the odds of being enrolled in school is 2 times higher for those working compared to those not working, and an OR of .50 means that the odds of being enrolled in school for workers is half that of non-workers. We also report predicted probabilities of school enrollment for children engaged in child labor (controlling covariates) as well as the difference in the predicted probabilities of school enrollment for children who are and are not engaging in child labor. A negative difference score indicates that those engaging in child labor had a lower probability of school enrollment than those not engaging in child labor. Finally, we report 2 estimates of variance in school enrollment accounted for by the full models including covariates and moderators, Cox and Snell’s and Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2.

We used child age and primary caregiver education as covariates. Because of the change in the number of hours of work outside the home and family work that were defined as child labor at age 12, older children were slightly less likely to engage in child labor overall, r(186,183) = −.04, p < .001, work outside the home, r(186,450) = −.04, p < .001, and family work, r(186,241) = −.08, p < .001, but older children were more likely to engage in excessive household chores, r(186,242) = .08, p < .001. Child age was not associated with school enrollment, r(184,997) = −.00, p = .097. Children whose primary caregiver had higher levels of education were less likely to engage in all forms of labor, rs(185,874 to 186,137) = −.05 to −.18, ps < .001, and were more likely to be enrolled in school, r(184,713) = .32, p < .001. Controlling child age and caregiver education in the analyses helps to remove factors that might otherwise inflate estimates of relations between child labor and school enrollment.

Results

Country-Level Relations Between Child Labor and Schooling

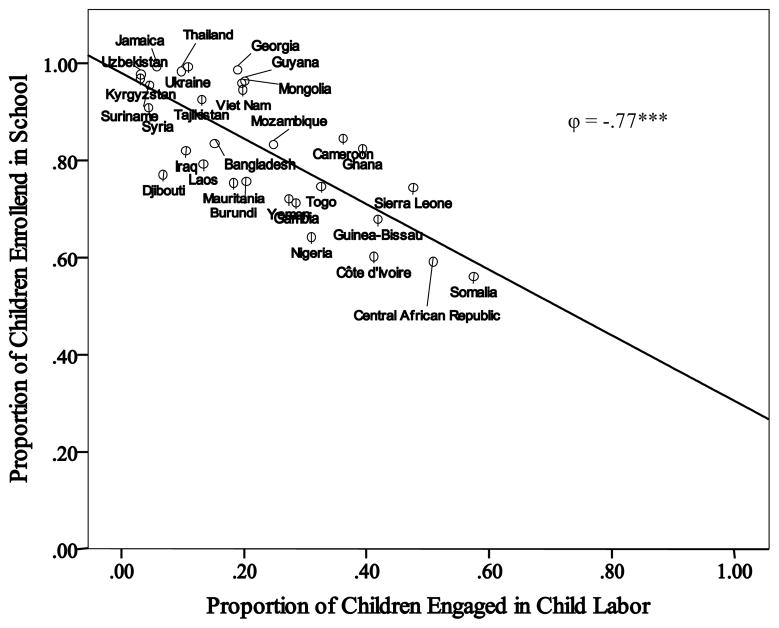

At the country level, significant relations emerged between child labor and school enrollment for the child labor index, φ(28) = −.77, p < .001 (Figure 1), family labor, φ(28) = −.76, p < .001, and excessive household chores, φ(28) = −.53, p = .003, but not work outside the home, φ(28) = −.22, p = .213. Relations (or lack thereof) between child labor and schooling at the country level are suggestive, but they do not help to explain whether child labor is consistently related to schooling at the family level within countries controlling for other relevant child and family characteristics. This is what we turn to next.

Figure 1.

Country-level relations between the child labor index and school enrollment.

Family-level Relations Between Child Labor and School Enrollment

Child labor index

Excluding 6 countries with inadequate data (see Analytic Plan and Table 1), and controlling for child age and caregiver education in logistic regression analyses, a significant interaction emerged for Child labor x Child gender x Country, Wald χ2(23) = 125.01, p < .001, as well as Child labor x Country, Wald χ2(23) = 1601.84, p < .001, but not Child labor x Child gender, Wald χ2(1) = 2.28, p = .131. There was also a significant main effect of child labor, Wald χ2(1) = 1641.89, p < .001, OR = .55, but it should be interpreted in the context of the higher-order interactions (i.e., the effect varied across countries). Overall, including child age, caregiver education, country, child gender, and child labor, the model accounted for 16% (Cox & Snell R2) to 25% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in school enrollment.

To interpret the 2- and 3-way interactions with country, we performed Child labor x Gender logistic regressions controlling for child age and caregiver education in each country separately. There were significant Child labor by Gender interactions in 10 countries, but the direction of effects was mixed. Child labor was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for girls than boys in Bangladesh, Wald χ2(1) = 47.27, p < .001, OR = 1.64, Laos, Wald χ2(1) = 10.22, p < .001, OR = 2.10, Vietnam, Wald χ2(1) = 4.55, p = .033, OR = 1.93, and Yemen, Wald χ2(1) = 6.83, p = .009, OR = 1.72 (the relation was nonsignificant for boys in Laos and Yemen). Child labor was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for boys than girls in Iraq, Wald χ2(1) = 5.17, p = .023, OR = .71, Mauritania, Wald χ2(1) = 4.12, p = .042, OR = .71, Sierra Leone, Wald χ2(1) = 6.68, p = .010, OR = .70, Somalia, Wald χ2(1) = 6.45, p = .011, OR = .68, and Syria, Wald χ2(1) = 6.20, p = .013, OR = .54 (the relation was nonsignificant for girls in Mauritania). Engaging in child labor was related to a higher probability of school enrollment for girls and a lower probability of school enrollment for boys in Guinea-Bissau, Wald χ2(1) = 5.48, p = .019, OR = .72, but both effects were nonsignficant. Aggregating across genders, child labor was associated with a significantly lower probability of school enrollment in 15 countries, a higher probability of school enrollment in 2, and was unrelated to school enrollment in 7 (Table 1).

Because the three kinds of child labor might differentially relate to school enrollment, and the prevalences of the three different types of child labor differ among girls and boys (Putnick & Bornstein, in press), we evaluated relations of work outside the home, family work, and excessive chores with school enrollment separately.

Work outside the home

Excluding 10 countries with inadequate data (see Supplementary Table S2), and controlling for child age and caregiver education in logistic regression analyses, significant interactions emerged for Child labor x Child gender x Country, Wald χ2(19) = 95.86, p < .001, as well as Child labor x Country, Wald χ2(19) = 1146.06, p < .001, and Child labor x Child gender, Wald χ2(1) = 39.54, p < .001. There was also a significant main effect of child labor, Wald χ2(1) = 911.98, p < .001, OR = .46, but it should be interpreted in the context of the higher-order interactions (i.e., the effect varied across countries and genders). Overall, including child age, caregiver education, country, child gender, and child labor, the model accounted for 13% (Cox & Snell R2) to 20% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in school enrollment.

To interpret the 2- and 3-way interactions with country, we performed Child labor x Gender logistic regressions controlling for child age and caregiver education for each country separately. There were significant Child labor by Child gender interactions in four countries. Work outside the home was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for boys than girls in Bangladesh, Wald χ2(1) = 66.43, p < .001, OR = .34, Iraq, Wald χ2(1) = 14.75, p < .001, OR = .29, and Yemen, Wald χ2(1) = 6.25, p = .012, OR = .23 (the relation was nonsignificant for girls in Iraq and Yemen). Work outside the home was associated with a higher probability of school enrollment for girls and was unrelated to school enrollment for boys in Cameroon, Wald χ2(1) = 8.75, p = .003, OR = .44. Aggregating across genders, work outside the home was associated with a significantly lower probability of school enrollment in 7 countries, a higher probability of school enrollment in 1, and was unrelated to school enrollment in 12 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratios, predicted probabilities, and difference in predicted probabilities for the main effects of work outside the home, family work, and excessive household chores predicting school enrollment

| Country | Work outside the home | Family work | Household chores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| OR | Predict. Prob.b | Diff. prob.c. | OR | Predict. Prob.b | Diff. prob.c. | OR | Predict. Prob.b | Diff. prob.c. | |

| Bangladesh | .11*** | .36 | −.62 | .64*** | .76 | −.12 | .10*** | .34 | −.64 |

| Burundi | .22*** | .41 | −.53 | .86 | .73 | −.06 | .35*** | .52 | −.38 |

| Cameroon | 1.71*** | .90 | .14 | 1.71*** | .90 | .14 | .32*** | .64 | −.31 |

| Central African Republic | .98 | .58 | −.01 | .86* | .56 | −.07 | 1.01 | .59 | .00 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | .80 | .55 | −.11 | .61*** | .48 | −.23 | .41*** | .38 | −.40 |

| Djibouti | .96 | .76 | −.01 | .93 | .76 | −.03 | -- | -- | -- |

| Gambia | .98 | .71 | −.01 | .68*** | .63 | −.16 | 1.48 | .79 | .16 |

| Georgia | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ghana | .76 | .78 | −.08 | .61*** | .74 | −.14 | .46*** | .68 | −.23 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1.09 | .70 | .04 | 1.05 | .69 | .02 | 1.11 | .70 | .05 |

| Guyana | -- | -- | .79 | .96 | −.02 | -- | -- | -- | |

| Iraq | .39*** | .64 | −.28 | .45*** | .67 | −.24 | .33*** | .60 | −.33 |

| Jamaica | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Kyrgyzstan | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Laos | .42*** | .62 | −.28 | .83 | .76 | −.06 | .24*** | .48 | −.46 |

| Mauritania | .65 | .66 | −.16 | .75** | .69 | −.11 | .76 | .70 | −.10 |

| Mongolia | -- | -- | -- | .51** | .92 | −.06 | .53* | .93 | −.05 |

| Mozambique | .73 | .79 | −.09 | .93 | .82 | −.02 | 1.11 | .85 | .03 |

| Nigeria | .57*** | .51 | −.25 | 1.82*** | .77 | .27 | 1.14 | .67 | .06 |

| Sierra Leone | 1.03 | .75 | .01 | .58*** | .63 | −.20 | .44*** | .56 | −.31 |

| Somalia | .50** | .39 | −.33 | .49*** | .38 | −.34 | .79** | .50 | −.12 |

| Suriname | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Syria | .05*** | .33 | −.67 | .32*** | .76 | −.21 | -- | -- | -- |

| Tajikistan | 1.89 | .96 | .09 | -- | -- | -- | 1.22 | .94 | .03 |

| Thailand | -- | -- | -- | .46*** | .97 | −.03 | -- | -- | -- |

| Togo | 1.01 | .75 | .00 | .70*** | .67 | −.13 | .43*** | .56 | −.31 |

| Ukraine | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Uzbekistan | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Vietnam | -- | -- | -- | .61** | .91 | −.05 | .55* | .91 | −.06 |

| Yemen | .82 | .68 | −.08 | .87 | .69 | −.06 | .47*** | .55 | −.30 |

|

| |||||||||

| TOTALa | .46*** a | .61 a | −.27 a | .76*** a | .75 a | −.09 a | .48*** a | .62 a | −.26 a |

Note. OR = Odds Ratio.

-- = Statistics were not computed because there were <5 cases expected in more than one cell in the contingency table between labor and school enrollment by gender (Rosner, 1995).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Excluding countries with no statistics above.

Predicted probability of being enrolled in school if engaging in child labor, controlling for child gender and age, and caregiver education.

Difference in the predicted probabilities of being enrolled in school if not engaging in child labor and if engaging in child labor, controlling for child gender and age, and caregiver education.

Family work

Excluding 7 countries with inadequate data (see Supplementary Table S3), and controlling for child age and caregiver education in logistic regression analyses, a significant interaction emerged for Child labor x Child gender x Country, Wald χ2(22) = 44.30, p = .003, as well as Child labor x Country, Wald χ2(22) = 450.84, p < .001, and Child labor x Child gender, Wald χ2(1) = 4.07, p = .044. There was also a significant main effect of child labor, Wald χ2(1) = 248.70, p < .001, OR = .76, but it should be interpreted in the context of the higher-order interactions (i.e., the effect varied across countries and genders). Overall, including child age, caregiver education, country, child gender, and child labor, the model accounted for 15% (Cox & Snell R2) to 23% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in school enrollment.

To interpret the 2- and 3-way interactions with country, we performed Child labor x Gender logistic regressions controlling for child age and caregiver education for each country separately. There were significant Child labor by Gender interactions in five countries, but the direction of effects was mixed. Family work was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for boys than girls in Côte d’Ivoire, Wald χ2(1) = 5.16, p = .023, OR = .77, and Sierra Leone, Wald χ2(1) = 4.69, p = .030, OR = .74. Family work was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for girls but not boys in Laos, Wald χ2(1) = 5.64, p = .018, OR = 1.90, and Vietnam, Wald χ2(1) = 7.24, p - .007, OR = 2.49. Finally, family work was associated with a higher probability of school enrollment for girls and a lower probability of school enrollment for boys in Guinea-Bissau, Wald χ2(1) = 5.19, p = .023, OR = .73, but both effects were nonsignficant. Aggregating across genders, family work was associated with a significantly lower probability of school enrollment in 14 countries, a higher probability of school enrollment in 2, and was unrelated to school enrollment in 7 (Table 2).

Household chores

Excluding 10 countries with inadequate data (see Supplementary Table S4), and controlling for child age and caregiver education in logistic regression analyses, a significant interaction emerged for Child labor x Child gender x Country, Wald χ2(19) = 45.34, p < .001, as well as Child labor x Country, Wald χ2(19) = 1059.23, p < .001, and Child labor x Child gender, Wald χ2(1) = 4.76, p = .029. There was also a significant main effect of child labor, Wald χ2(1) = 678.98, p < .001, OR = .48, but it should be interpreted in the context of the higher-order interactions (i.e., the effect varied across countries and genders). Overall, including child age, caregiver education, country, child gender, and child labor, the model accounted for 14% (Cox & Snell R2) to 21% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in school enrollment.

To interpret the 2- and 3-way interactions with country, we performed Child labor x Gender logistic regressions controlling for child age and caregiver education for each country separately. There were significant Child labor by Child gender interactions in four countries, but the direction of effects was mixed. Engaging in excessive chores was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for girls than boys in Bangladesh, Wald χ2(1) = 9.70, p = .002, OR = 1.73, and Yemen, Wald χ2(1) = 10.10, p < .001, OR = 2.58 (the relation was nonsignificant for boys in Yemen). Engaging in excessive chores was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for boys but not girls in Mongolia, Wald χ2(1) = 4.94, p = .026, OR = .26, and Somalia, Wald χ2(1) = 7.70, p = .006, OR = .63. Aggregating across genders, engaging in excessive chores was associated with a significantly lower probability of school enrollment in 13 countries, and was unrelated to school enrollment in the remaining 7 (Table 2).

Discussion

Considering all countries together, we found significant negative relations between all forms of child labor and school enrollment. However, these relations were moderated (not uniform) by country and child gender and effects were generally small to medium in size, leaving a great deal of variance in school enrollment attributable to unmeasured factors, such as school availability, quality, and cost, distance to the school, parental cognitions about schooling, and child cognitive ability.

Moderation by Country

At the country level, there was a large relation between child labor and school enrollment for the index (Figure 1), family work, and excessive household chores, but not work outside the home. Like the other indicators of child labor, work outside the home had a negative relation with school enrollment, but the effect size was small and with a sample size of 30 countries, this effect did not reach statistical significance. However, the family-level analyses (which had more than adequate statistical power) supported this pattern, with labor related to enrollment in more than half of countries for the index, family work, and excessive household chores, but not work outside the home.

For the child labor index, engaging in child labor was associated with a reduced likelihood of school enrollment in over 62% of the countries for which there were adequate data. However, in 2 countries (8%; Gambia and Nigeria), engaging in child labor was associated with a greater likelihood of school enrollment, and labor was unrelated to school enrollment in the remaining 29% of countries. Engaging in work outside the home was associated with a reduced likelihood of school enrollment in only 35% of the countries, a greater likelihood of school enrollment in 1 country (5%; Cameroon), and was unrelated to school enrollment in the remaining 60% of countries. Engaging in family work was associated with a reduced likelihood of school enrollment in 61% of the countries, a greater likelihood of school enrollment in 2 countries (9%; Cameroon and Nigeria), and was unrelated to school enrollment in the remaining 30% of countries. Finally, engaging in excessive household chores was associated with a reduced likelihood of school enrollment in 65% of the countries and was unrelated to school enrollment in the remaining 35% of countries. Work outside the home was related to school enrollment in the smallest number of countries. Work outside the home, or economic work, has received the most empirical attention, but children engage in family work and household chores at higher rates in these LMIC and the two were more consistently related to lower school enrollment rates across countries. Hence, the research focus on economic work may be misplaced.

Looking across the three types of child labor, in 19 of the 24 countries (79%) for which there were adequate data, at least one type of child labor was negatively related to school enrollment (all three types of labor were negatively related to enrollment in Bangladesh, Iraq, Mongolia, Somalia, Syria, Thailand, and Vietnam). There were only five countries (21%) in which child labor had no significant relation with school enrollment: Djibouti, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Mozambique, and Tajikistan. These five countries had varying rates of child labor (6.8% to 41.7% based on the index), but the children who were engaged in labor were generally also enrolled in school (64.6% to 96.1%). Guyana and Tajikistan both had very high school enrollment rates regardless of child labor. Some countries (e.g., Guinea-Bissau, Djibouti, and Mozambique) have double- or triple-shift schooling (i.e., two or three daily school sessions) to accommodate more students in a single school building or to allow children to work for part of the day and attend school the rest. These policies may make it easier for children to combine work and school. Whatever the reason, child labor does not seem to be a significant barrier to school enrollment in these five countries. Nevertheless, child labor may have negative relations with other aspects of schooling, such as attendance (Guarcello et al., 2008) and performance (Heady, 2003; Orazem & Gunnarsson, 2003) as well as future earnings (Emerson & Souza, 2007; Knaul, 2001). Combining work and school may also have a slight negative impact on child well-being (e.g., higher emotional, social, and conduct problems) relative to just working (Al-Gamal, Hamdan-Mansour, Matrouk, & Al Nawaiseh, 2013) or just attending school.

Three countries had positive relations between one or more indicators of child labor and school enrollment: Cameroon, the Gambia, and Nigeria. In each case, one type of child labor had a negative relation with enrollment (chores for Cameroon, family work for Gambia, and work outside the home for Nigeria), whereas the others had positive or nonsignificant relations. Hence, in these three countries, some types of child labor were good while others were bad vis-à-vis school enrollment. One possible reason for these paradoxical effects is that many children are required to pay for transportation to school, books, school fees, or uniforms, and engaging in paid work may allow them to do so. When Nigerian children were asked about the benefits of working, the most common reasons cited were supporting the family and having money to pay for school or to learn a trade (Omokhodion, Omokhodion, & Odusote, 2006). In Cameroon, where free education was instituted in 2000, the government does not have adequate funds to pay all teachers and provide needed school supplies which forces schools to assess levies (Kindzeka, 2013). Consequently, working outside the home or for a family business may generate enough money to allow Cameroonian children to enroll in school, but engaging in excessive household chores may impede school enrollment because chores take many hours (≥ 28 by our definition) and do not generate income. Another possible reason for the positive relations between child labor and school enrollment is that certain types of work may keep children closer to school. For example, in Nigeria, working for the family is associated with a higher likelihood of school enrollment, but working outside the home is related to lower likelihood of enrollment. Although working outside the home may generate family income, it may also require children to travel far from home and therefore school, preventing them from enrolling in or attending school. Engaging in family work may generate income for the family and still allow children to remain at home and close to school.

Moderation by Gender

Moderation effects of gender were generally infrequent and unsystematic. Child gender moderated the effects of child labor on school enrollment in 17–42% of countries, depending on the type of child labor. For the child labor index, family work, and excessive household chores, countries were approximately split on whether labor had a greater association with boys’ than girls’ school enrollment or a greater association with girls’ than boys’ school enrollment. Only for work outside the home was the gender effect consistently in favor of girls (i.e., work outside the home was associated with a lower probability of school enrollment for boys’ than for girls’). These unsystematic effects are likely the result of complex relations between each country’s gender norms regarding child labor and schooling (Putnick & Bornstein, in press).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, notably (1) the large number of underresearched LMIC and large numbers of children in each country, (2) the inclusion of three types of child labor, and in particular family work and excessive household chores, which have been infrequently studied, and (3) the use of statistical controls and exploration of moderators. However, these strengths should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. Because the MICS3 is collected across many countries, the instruments used in this study were blunt (yes, no). Information that was gathered on child labor is also somewhat incomplete. No information was collected about the sector of work a child is doing (e.g., agricultural, trade, manufacturing), their working conditions, the types of tasks in which they engage while on the job (e.g., operating machinery, childcare, handling hazardous chemicals, cleaning), the psychosocial impact on the child (e.g., stressful and depressing vs. motivating and self-esteem building), and what factors drove the child to work (e.g., poverty, apprenticeship, illness of a parent, inaccessible schools). Similarly, even if a child was enrolled in school, MICS data reveal nothing about her or his school performance, the quality of the school, or the school’s relevance to the local economy. Although the MICS collects the days of school attendance in the previous week, regional differences in the availability of schooling make this variable difficult to analyze across countries and urban and rural regions within countries. School enrollment is a liberal indicator of schooling, which is only the first step toward academic success. Better data is needed on children’s working conditions, psychosocial well-being, cognitive skills, and school performance as well as family and cultural factors that lead to the decision to choose child labor, schooling, or both.

Policy Implications

Because the effects of child labor on school enrollment were moderated by country and gender, there is no one clear “fix” for child labor. Some governmental and non-governmental organizations have focused on global legislation, like setting a minimum age for child labor or banning child labor altogether. These strategies will likely fail to eradicate child labor and improve living conditions for children (Budhwani, Wee, & McLean, 2004; Morrow, 2010) because a host of factors promotes or maintains child labor, including (but not limited to) the unavailability or prohibitive costs of quality schooling, gender-based cultural norms, the unavailability of alternative labor sources, and individual family needs. For example, there is some evidence that a national ban on child labor only serves to push children into lower-paying and less regulated jobs, which encourages parents to send children into labor more (Bharaswaj, Lakdawala, & Li, 2013; Edmonds, 2003).

Dessy (2000) argued that free and compulsory education could improve later job prospects and encourage families to choose school over work, but some economic incentives (e.g., paying families that enroll children in school) may be needed to offset immediate family losses associated with removing children from the workforce. Most countries in this study have policies to provide free education, but the implementation of those policies may still be incomplete because of inadequate funding, infrastructure (e.g., rural schools), and availability of qualified teachers. Providing education that is truly costless to the family may be the best strategy for reducing child labor, but some families will still struggle to find alternative sources of inexpensive labor and childcare. Results of a conditional cash transfer program in Nicaragua indicated that compensating families for having a child enrolled in and attending school increased schooling and reduced child labor (Maluccio, 2009), but Ravallion and Wodon (2000) and Rosati, Manacorda, Kovrova, Koseleci, and Lyon (2011) both reported little effect of similar programs on child labor in Bangladesh and Brazil, respectively. Each country is affected by unique laws, social programs, job markets, cultural norms, and economics that filter down to family decisions to choose child labor over school. Programs to encourage families to choose school over work will likely need to be tailored to specific country, neighborhood, and family conditions.

Future Directions and Conclusions

This study explored relations between child labor and school enrollment, but there may be aspects of schooling beyond enrollment that are important to consider. For example, child labor may also negatively relate to school attendance and learning. Working children may be less likely to attend school regularly even if they are enrolled (Guarcello et al., 2008). Furthermore, child labor may adversely relate to math and reading test performance (Heady, 2003; Orazem & Gunnarsson, 2003). Future research should systematically investigate relations of different forms of child labor and the intensity of child labor (e.g., work hours) with diverse indicators of school success.

The results of this study point to the likelihood that each country will have unique factors that contribute to the decision to put a child to work and/or enroll a child in school. Prior to initiating policy changes or interventions to reduce child labor and encourage universal education, the target population should be thoroughly studied to deduce the particular factors that are operative in child labor/schooling decisions (e.g., the presence, relevance, cost, and proximity of schools, the family’s need for income or inability to pay other workers, child cognitive ability, the local economies, cultural norms, gender norms, etc.). Through understanding these factors, targeted policies and interventions could encourage more families to forego child labor, educate their children, and break the cycle of poverty.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Few multi-country, controlled studies of the relations between different kinds of child labor and schooling are available.

This study employs 186,795 families with 7- to 14-year-old children in 30 low- and middle-income countries to explore relations of children’s work outside the home, family work, and household chores with school enrollment.

Overall, negative relations emerged between each form of child labor and school enrollment, but relations were more consistent for family work and household chores than work outside the home.

All relations were moderated by country and sometimes by child gender.

Prior to initiating policy changes or interventions to reduce child labor and encourage universal education, the target population should be thoroughly studied to deduce the particular factors that are operative in child labor/schooling decisions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NICHD. We thank UNICEF and participating countries for collecting the data. DLP conceived the study, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft. MHB participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Gamal E, Hamdan-Mansour AM, Matrouk R, Al Nawaiseh M. The psychosocial impact of child labour in Jordan: A national study. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48:1156–1164. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2013.780657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allais FB. Assessing the gender gap: Evidence from SIMPOC surveys. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/viewProduct.do?productId=10952. [Google Scholar]

- Amin S, Quayes S, Rives JM. Market work and household work as deterrents to schooling in Bangladesh. World Development. 2006;34:1271–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Beegle K, Dehejia R, Gatti R. Why should we care about child labor? The education, labor market, and health consequences of child labor. The Journal of Human Resources. 2009;44:871–889. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra MEG, Kassouf AL, Arends-Kuenning M. The impact of child labor and school quality on academic achievement in Brazil. Discussion Paper No. 4062. 2009 Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp4062.pdf.

- Bharaswaj P, Lakdawala LK, Li N. Perverse consequences of well intentioned regulation: Evidence from India’s child labor ban. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w19602.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Putnick DL. Housing quality and access to material and learning resources within the home environment in developing countries. Child Development. 2012;83:76–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani NN, Wee B, McLean GN. Should child labor be eliminated? An HRD perspective. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2004;15:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dessy SE. A defense of compulsive measures against child labor. Journal of Development Economics. 2000;62:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Diallo Y, Hagemann F, Etienne A, Gurbuzer Y, Mehran F. Global child labour developments: Measuring trends from 2004 to 2008. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/viewProduct.do?productId=13313. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds EV. Should we boycott child labor? Ethics and Economics. 2003;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds EV, Pavcnik N. Child labor in the global economy. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2005;19:199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson PM, Souza AP. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3027. Bonn, Germany: Iza; 2007. Is child labor harmful? The impact of working earlier in life on adult earnings. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp3027.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares J, Raju D. Child labor across the developing world: Patterns and correlations. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4119. 2007 Retrieved from http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2007/01/25/000016406_20070125152956/Rendered/PDF/wps4119.pdf.

- Galli R. ILO Discussion Paper. Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies; 2001. The economic impact of child labour. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_193680.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons ED, Huebler F, Loaiza E. Child labour, education, and the principle of non-discrimination. In: Alston P, Robinson M, editors. Human Rights and Development: Towards Mutual Reinforcement. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Goulart P, Bedi AS. Child labour and educational success in Portugal. Economics of Education Review. 2008;27:575–587. [Google Scholar]

- Guarcello L, Lyon S, Rosati FC. Child labour and education for all: An issue paper. Working paper. 2008 Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1780257.

- Heady C. The effect of child labor on learning achievement. World Development. 2003;31:385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Huebler F. Child labour and school attendance: Evidence from MICS and DHS surveys. Unpublished manuscript. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.childinfo.org/files/Child_labour_school_FHuebler_2008.pdf.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) User guide. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2006. Tackling hazardous child labour in agriculture. Guidance on policy and practice. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_2799/lang--en/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (ILO) Gender equality at the heart of decent work. Report IV of the International Labour Conference; Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_105119.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kindzeka ME. Cameroon struggles with universal education. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.voanews.com/content/universal-education-goal-elusive-in-cameroon/1741636.html.

- Knaul FM. The impact of child labor and school dropout on human capital: Gender differences in Mexico. In: Correia MC, Katz EG, editors. The economics of gender in Mexico: Work, family, state, and market. Directions in Development. Herndon, VA: World Bank Publications; 2001. pp. 46–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T, Ito S, Fuwa N, Kubo K, Sawada Y. Child labor and school enrollment in rural India: Whose education matters? The Developing Economies, XLIV-4. 2006:440–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lancy DF. The chore curriculum. In: Spittler G, Bourdillion M, editors. African children at work: Working and learning in growing up for life. Zürich, Switzerland: Lit Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:701–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluccio JA. Education and child labor: Experimental evidence from a Nicaraguan conditional cash transfer program. In: Orazem PF, Sedlacek G, Tzannatos Z, editors. Child Labor in Latin America: An Economic Perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2009. pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow V. Should the world really be free of ‘child labour’? Some reflections. Childhood. 2010;17:435–440. [Google Scholar]

- No F, Sam C, Hirakawa Y. Revisiting primary school dropout in rural Cambodia. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2012;13:573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Omokhodion FO, Omokhodion SI, Odusote TO. Perceptions of child labour among working children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006;32:281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orazem PF, Gunnarsson A. ILO/IPEC Working Paper. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2003. Child labour, school attendance and academic performance: A review. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/viewProduct.do?productId=716. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Girls’ and bBoys’ labor and household chores in low- and middle-income countries. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion M, Wodon Q. Does child labor displace schooling? Evidence on behavioral responses to an enrollment subsidy. Economic Journal. 2000;110(462):158–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Lancaster G. The impacts of children’s work on schooling: Multi country evidence. International Labour Review. 2005;144:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati FC, Manacorda M, Kovrova I, Koseleci N, Lyon S. Understanding the Brazilian success in reducing child labour: Empirical evidence and policy lessons. Understanding children’s Work Programme Working Paper Series. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.ucw-project.org/attachment/Brazil_20june1120110622_103357.pdf.

- Rosati FC, Rossi M. Children’s working hours and school enrollment: Evidence from Pakistan and Nicaragua. The World Bank Economic Review. 2003;17:283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 4. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2013. New York: United Nations; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Monitoring the situation of children and women: Multiple indicator cluster survey manual. New York: UNICEF; 2006. Retrieved from http://www.childinfo.org/files/Multiple_Indicator_Cluster_Survey_Manual_2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Progress for children: A world fit for children statistical review. Vol. 6. New York: UNICEF; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Progress_for_Children_No_6_revised.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human development indices: A statistical update. 2008 Retrieved from http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2009/03143.pdf.

- World Bank. 2012 World development indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2012. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/wdi-2012-ebook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. School enrollment, primary (% net) 2014 Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.NENR.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.