Abstract

Background

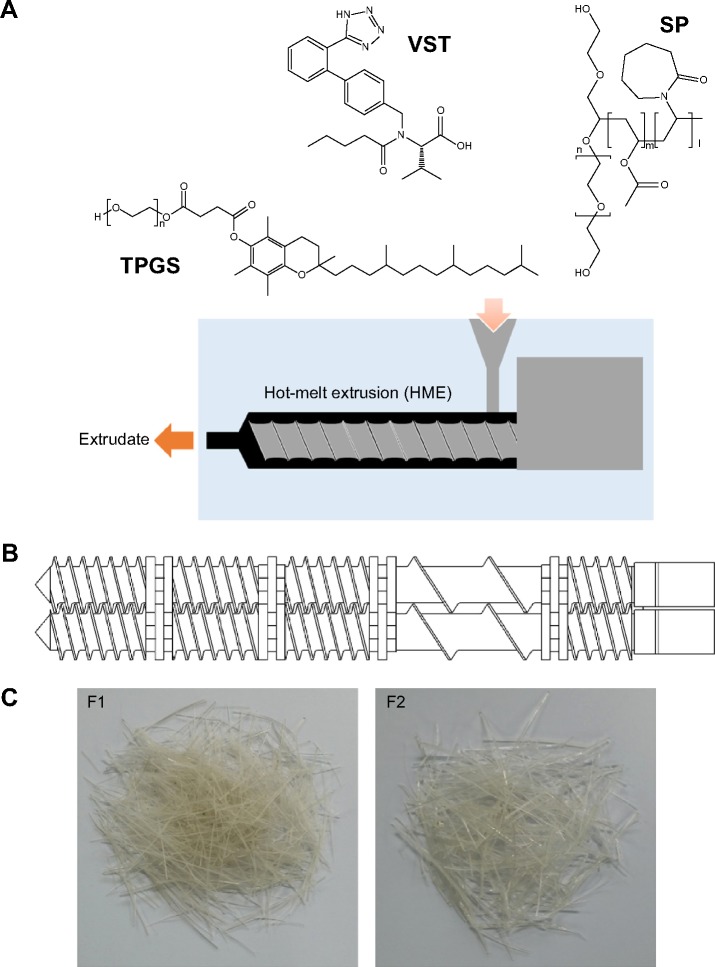

Soluplus® (SP) and D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS)–based solid dispersion (SD) formulations were developed by hot-melt extrusion (HME) to improve oral bioavailability of valsartan (VST).

Methods

HME process with twin-screw configuration for generating a high shear stress was used to prepare VST SD formulations. The thermodynamic state of the drug and its dispersion in the polymers were evaluated by solid-state studies, including Fourier-transform infrared, X-ray diffraction, and differential scanning calorimetry. Drug release from the SD formulations was assessed at pH values of 1.2, 4.0, and 6.8. Pharmacokinetic study was performed in rats to estimate the oral absorption of VST.

Results

HME with a high shear rate produced by the twin-screw system was successfully applied to prepare VST-loaded SD formulations. Drug amorphization and its molecular dispersion in the polymer matrix were verified by several solid-state studies. Drug release from SD formulations was improved, compared to the pure drug, particularly at pH 6.8. Oral absorption of drug in rats was also enhanced in SP and TPGS-based SD groups compared to that in the pure drug group.

Conclusion

SP and TPGS-based SDs, prepared by the HME process, could be used to improve aqueous solubility, dissolution, and oral absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs.

Keywords: hot-melt extrusion, oral bioavailability, solid dispersion, valsartan

Introduction

Many approaches have been used to prepare oral formulations of poorly water-soluble drugs to improve oral bioavailability.1–3 Among them, solid dispersion (SD), in which the drug molecule is dispersed in a polymeric matrix, has been shown to improve the aqueous solubility and oral absorption of drugs.4,5 SD produces these effects on poorly water-soluble drugs by increasing wettability, decreasing agglomeration, and altering the physical state of the drugs. Although SD formulations can be prepared by several methods, hot-melt extrusion (HME) is an attractive and emerging method for the production of SDs.6,7 The HME process has the advantage of being a continuous, solvent-free, dust-free (environmentally friendly), and robust manufacturing process, as well as possessing the ability to yield several solid dosage forms (eg, pellets or tablets).8 During the HME process, shear stress generated by extruder screws can be applied to overcome the crystal lattice energy of crystalline drugs and soften polymers. The mixing and dispersing of the drugs and polymers occur inside the extruder, from which the melted product is extruded. SDs can be defined as eutectics, crystalline dispersions, and solid solutions,9 according to the state (crystalline, amorphous, or molecularly dispersed) of the matrix and the drug, as well as the number of phases. The physicochemical properties of SDs can be influenced the HME equipment used (eg, feeder, barrels, and die) and the extrusion processing parameters (eg, barrel and temperatures, screw speed, melt pressure, torque, screw configuration, etc). Generally, the HME process temperature is set 20°C–30°C lower than the melting point of the drug.8 Furthermore, the glass transition temperature (Tg or melting temperature (Tm) of the polymers should considered. Among several polymers that are suitable for the HME process, Soluplus® (SP) and D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) were chosen for this investigation. SP (Tg of approximately 70°C), amphiphilic copolymer composed of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000, vinylcaprolactam, and vinyl acetate, has been used as a drug solubilizer and permeation enhancer across biological membranes.10,11 TPGS is a D-alpha-vitamin E ester derived from vitamin E, and its Tm is approximately 40°C.12 TPGS can be used as a nonionic surfactant due to its amphiphilic properties, and it can improve the solubility and permeability of poorly water-soluble drugs and stabilize amorphous drugs in SDs.13 The Tg and Tm values of SP and TPGS seem to be appropriate for HME processing.

In this study, SD formulations processed by HME were developed for the oral delivery of valsartan (VST). VST is a selective angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist used for the treatment of hypertension. VST has relatively low aqueous solubility (<0.1 mg/mL) and low oral bioavailability (<25%) due to poor solubility in acidic solutions.14 The pH-dependent drug release can induce inter- and intrasubject variability in drug absorption. To solve these drawbacks, several oral formulations have been developed for VST delivery.14–16 Although SD formulations using VST have already been reported,17 the application of HME technique to their preparation has not been investigated.

Herein, we report the development and evaluation of SDs based on SP and TPGS, processed by the HME method with a high shear, for the oral delivery of VST. To the best of our knowledge, high shear-driven HME-processed SDs based on SP and TPGS have not been reported for oral delivery of VST. Solid-state studies were performed to evaluate drug amorphization and dispersion in the polymer matrix. Furthermore, we investigated VST drug release in vitro and pharmacokinetics in vivo.

Materials and methods

Materials

VST was purchased from Tecoland Corp (Irvine, CA, USA). SP and TPGS were obtained from BASF SE (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Phosphoric acid and hydrochloric acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile and other organic solvents were acquired from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL, USA). Double deionized water (DDW) was prepared using Super-Q Plus Water Purification Systems (Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Preparation of VST-loaded SDs

Drug and polymers (about 250 g of the total amount) were blended for 3 minutes prior to extrusion according to the ratios presented in Table 1. These mixtures were fed into a twin-screw hot-melt extruder (STS-25HS, Hankook EM Ltd, Pyoung-Taek, Korea) equipped with a round-shaped die (1 mm in diameter). The temperatures of the heating zones were maintained as shown in Table 2. The extrusion rate was 28–30 g/min and the extrusion pressure was about 100 bars. The speed of the screw was set at 150 rpm. Extrudates were cooled to room temperature and milled for pulverization. A sieve with 0.21 mm wire width (70 mesh) was used to prepare the powders.

Table 1.

Composition of the formulations (F1 and F2) developed in this study

| Component | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| SP | 70% | 60% |

| TPGS | 0% | 10% |

| VST | 30% | 30% |

Abbreviations: SP, Soluplus; TPGS, D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate; VST, valsartan; F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study.

Table 2.

Temperature of heating zone in the hot-melt extruder

| Formulation | Temperature of heating zone (°C)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Adapter | Die | |

| F1 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| F2 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Abbreviation: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study.

Characterization of VST-loaded SDs

The dispersion of drug molecules in the polymer matrix and the transition between crystalline and amorphous forms were investigated by solid-state studies. FT-IR spectra of VST, SP, and TPGS, as well as the SD formulations F1 and F2, were obtained by a Jasco FT/IR-4200 type A (Jasco Co, Tokyo, Japan) instrument with the KBr method. All samples were scanned in the range of 600–4,000 cm−1.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed with a D5005 model diffractometer (Bruker, Germany) at room temperature. Monochromatic Cu-Kα radiation (λ=1.5406 Å) was used in the 2θ angle range from 6° to 40°, with an angular increment of 0.02°/s and a scan speed of 1°/min at 40 mA and 40 kV.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2 were obtained with a DSC-Q100 instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). DSC analysis of the SD formulations F1 and F2 after 6 months of storage at room temperature was also performed. Thermograms were scanned with aluminum from 30°C to 190°C at a speed of 10°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL/min).

In vitro drug release

In vitro drug release was measured with a dissolution tester (TDT-08L; Electrolab, Maharashtra, India). The VST powder and formulations (F1 and F2), each containing 20 mg VST, were encapsulated in gelatin capsules and immersed in 900 mL of dissolution media (pH 1.2: containing hydrochloric acid and 0.3% Tween 80; pH 4.0: acetate buffer containing 0.3% Tween 80; pH 6.8: containing phosphoric acid) at 37°C and stirred at 100 rpm. Aliquots (7 mL) of the dissolution media were collected at predetermined times (15 minutes, 30 minutes, 45 minutes, 60 minutes, 90 minutes, and 120 minutes) and an equivalent volume of fresh medium was added at each sampling time to compensate. The released VST was quantitatively analyzed with a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters Co, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a reversed-phase C18 column (UniverSil C18, 150×4.6 mm, 5 μm; Fortis Technologies Ltd, Cheshire, UK), a pump (Waters 1525), an automatic injector (Waters 717 plus), and an ultraviolet/visible detector (Waters 2487). The mobile phase was composed of acetonitrile and DDW (60:40, v/v) with pH adjusted to 3.0 with phosphoric acid. The detection wavelength and flow rate were 247 nm and 1.0 mL/min, respectively. The injection volume was 20 μL, and the retention time of VST was 3.3 minutes. The correlation coefficient (r2) of the linear regression line was 0.999 in this method. The accuracy and precision values of the inter- and intra-day samples were 92.9%–109.4% and 0.1%–5.5%, respectively.

In vivo pharmacokinetic study

In vivo pharmacokinetic studies were performed in male Sprague Dawley rats (250±5 g body weight; Orient Bio, Sungnam, Korea). The rats were reared in a light-controlled room at a temperature of 22°C±2°C and 55%±5% relative humidity. The experimental protocols of the animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Pharmacy (Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea; No SNU-130722-1-1).

The left femoral artery was cannulated with a polyethylene tube (PE-50; Becton Dickinson Diagnostics, MD, USA) under Zoletil (Virbac, Carros, France) anesthesia (50 mg/kg, intramuscular injection). VST powder or the SD formulations were encapsulated in gelatin microcapsules (Torpac Inc, Fairfield, NJ, USA) and administered orally at a dose of 4 mg/kg. Blood samples (200 μL) were collected from the femoral artery at 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 45 minutes, 60 minutes, 90 minutes, 120 minutes, 240 minutes, 480 minutes, and 1,440 minutes after VST administration, and an equivalent volume of normal saline (containing 20 U/mL heparin) was administered at each sampling time. The blood samples were centrifuged at 16,000× g for 3 minutes at 4°C. The aliquots (70 μL) of plasma were stored at −70°C before the quantitative analysis of drug.

VST concentrations in rat plasma were determined by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). To each 50 μL plasma sample, 5 μL of losartan (LST, internal standard) solution (15 μg/mL) and 145 μL of acetonitrile were added, and the sample was vortexed for 5 minutes. After centrifugation at 16,000× g for 5 minutes, the supernatant (2 μL) was injected into the LC-MS/MS system, equipped with an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Agilent Technologies 6430 Triple Quad LC/MS system. The chromatographic separation was achieved using Synergi™ 4 μ Hydro-RP 80 Å column (75×2.0 mm; Phenomenex, CA, USA). The mobile phase was composed of acetonitrile and 5 mM ammonium formate buffer (85:15, v/v) and the flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. The electrospray ionization source settings were optimized manually. The gas temperature, gas flow, nebulizer pressure, and capillary voltage were 300°C, 11 L/min, 30 psi, and 4,000 V, respectively. The fragmentation transitions were mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 436.2 to m/z 291.2 for VST and m/z 423.4 to m/z 207.3 for LST. The fragmentor voltage and collision energy for VST were 98 V and 14 eV, respectively, and were 115 V and 20 eV, respectively, for LST. The retention times of VST and LST were 0.46 minutes and 0.47 minutes, respectively. The accuracy and precision values of samples were 86.4%– 107.9% and 2.0%–6.3%, respectively. The acquisition and processing were performed with MassHunter Workstation Software Quantitative Analysis (Version B.05.00; Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Pharmacokinetic parameters for VST were calculated with WinNonlin (Version 3.1; Pharsight, Mountain View, CA, USA): total area under the plasma VST concentration– time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC), peak plasma concentration (Cmax), and time to reach Cmax (Tmax).

Histological study

Histological assays were performed to assess the toxicity of the tested formulations to the intestinal epithelium. Pure VST and VST-loaded formulations (F1 and F2) were orally administered to Sprague Dawley rats (4 mg/kg), and the rats were sacrificed at 24 hours postadministration. The jejunum was obtained by dissecting the peritoneal membrane, and it was fixed in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde solution for 1 day. Fixed tissues were rinsed with DDW, dehydrated with alcohol, and embedded in paraffin. Tissues were cut into 5–10 μm thick sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) reagent. Microscopic images were acquired to evaluate the mucosal toxicity of the formulations.

Statistical analysis

All experiments in drug dissolution and animal studies were repeated at least three times, and the data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis (ie, analysis of variance) was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). A P-value <0.05 was regarded as significantly different.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of VST-loaded SD formulations

The HME technique was used in the preparation of oral SDs of VST (Figure 1A). According to the ratios presented in Table 1, the drug was homogeneously dispersed in the polymer using a solvent-free continuous process. In our preliminary study, SD formulations based on 9:1, 7:3, and 5:5 weight ratios of polymer to drug were prepared, and drug release profiles were tested. On the basis of the ease of HME processing and the drug dissolution data, a ratio of 7:3 by weight (polymer to drug) was finally selected for SD formulation development. SP and TPGS were used as the main matrix and plasticizer, respectively, with the aim of enhancing drug solubilization and absorption.10,12 The Tm of VST in this investigation was 104.6°C, which was similar to previously reported values.17 Given the Tm and Tg values of the drug and the polymers, the temperature of the melting extrusion process was set at 80°C–100°C, as shown in Table 2. In general, the temperature of the heating zone can be set 15°C–60°C above the Tm of semicrystalline polymers or the Tg of amorphous polymers.18 The established temperature (80°C–100°C) was sufficient to allow for the successful extrusion of polymers. In addition, knowledge of thixotropic behavior, which describes the decrease in viscosity of a polymer with an increase in shear stress, can guide the process of blending and codispersing drugs and polymers. It is known that the addition of plasticizers, such as the TPGS included in the F2 formulation (Table 1), can decrease Tg and the melting viscosity of polymers during extrusion processing.19 The use of high-shear twin screws and a die with a 1 mm diameter also contributed to the production of a homogeneous extrudate (Figure 1B and C). As shown in Figure 1B, multiple kneading disk blocks were introduced to the full flight screw for generating a high shear stress. It is noteworthy that the twin-screw extruder can alter both the crystallinity of a drug and its release characteristics from SD formulations.20 Moreover, high shear rates, as determined by the screw configuration, can result in a more efficient melting process and can produce extrudates with low viscosity.

Figure 1.

Preparation of VST-loaded SD formulations.

Notes: (A) Schematic illustration of the herein-developed formulations with hot-melt extruder is presented. (B) Twin-screw configuration for generating a high shear is illustrated. (C) Images of extrudates (corresponding to F1 and F2) are shown.

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; SD, solid dispersion; SP, Soluplus; TPGS, D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate; VST, valsartan.

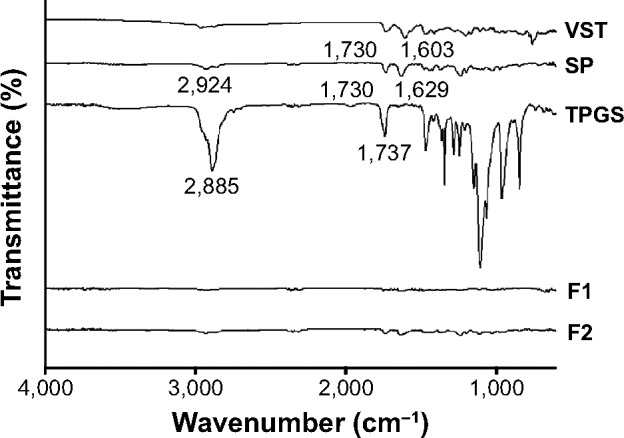

As shown in Figure 1, VST (active pharmaceutical ingredient [API]), SP, and TPGS were fed into the extruder. The molecularly dispersed API in the polymer matrix was confirmed by solid-state studies (Figures 24). The FT-IR spectra of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2 are shown in Figure 2. VST has two carbonyl absorption bands at 1,730 cm−1 (C=O group) and imine band at 1,603 cm−1 (C=N band).14 The spectrum of SP exhibits a peak at 2,924 cm−1 (aliphatic C–H stretching), as well as at 1,730 cm−1 and 1,629 cm−1 (C=O stretching).8 The TPGS spectrum has peaks at 2,885 cm−1 (aliphatic C–H stretching) and 1,737 cm−1 (C=O stretching). The alteration of the representative peaks of VST in the spectra of the F1 and F2 formulations suggested intermolecular interactions between the drug and the polymers (SP and TPGS).

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2.

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; FT-IR, Fourier-transform infrared; SP, Soluplus; TPGS, D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate; VST, valsartan.

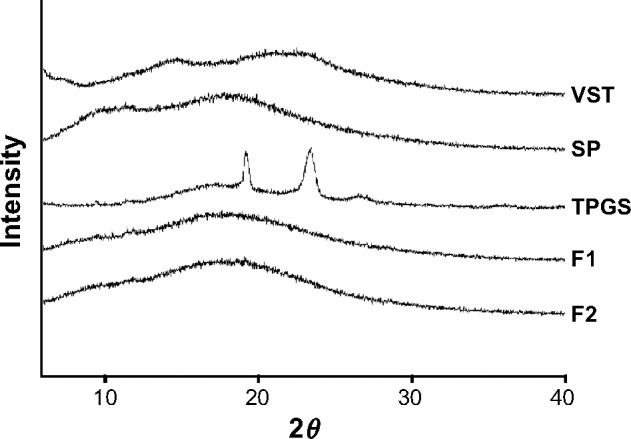

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2.

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; SP, Soluplus; TPGS, D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate; VST, valsartan; XRD, X-ray diffraction.

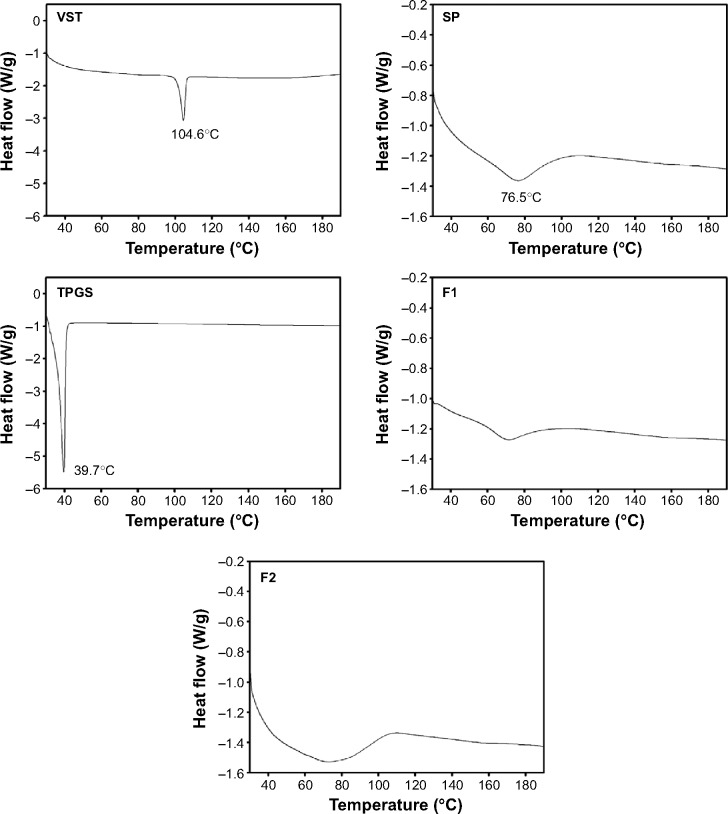

Figure 4.

DSC results of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2.

Abbreviations: DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; SP, Soluplus; TPGS, D-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate; VST, valsartan.

The XRD patterns of VST, SP, TPGS, F1, and F2 are presented in Figure 3. The diffractogram of VST exhibited a strong broad peak, as previously reported.17,21 Unprocessed SP exhibited an amorphous halo without crystallinity, as previously reported.22 In contrast, the crystallinity of TPGS was shown by its XRD pattern.12 The XRD results of F1 and F2 suggested the generation of interactions between drug and polymer molecules by HME processing.

The thermal behaviors of the drug, the polymers, and the formulations were evaluated by DSC (Figure 4). The DSC curve of VST had a sharp endothermic peak at 104.6°C, which indicated the crystallinity and melting point of the drug.17 The DSC thermogram of SP exhibited a broad peak around 70°C, indicating the transition of the amorphous polymer from a glassy state to a rubbery state with enthalpy relaxation.8 The thermogram of TPGS included an endothermal peak at 39.7°C, indicating its crystallinity and Tm value, which corresponded with previously reported results.23 The disappearance of the sharp endothermal peak of VST in the thermograms of F1 and F2 revealed that the drug was altered from a crystalline to an amorphous form during the HME process. The results from these solid-state studies indicated the amorphization of the drug and its dispersion in the polymer matrix. Over time, an amorphous drug with a higher energy level tends to transform to a crystalline form with a lower free energy.24,25 Several factors, including atmospheric moisture and residual crystalline drug (acting as a seed crystal), can accelerate the transformation from an amorphous to a crystalline state during storage.7 One common strategy to inhibit recrystallization of drugs is to prepare SDs. In this investigation, DSC thermo-grams of F1 and F2 (after 6 months at room temperature) were acquired and are shown in Figure S1. A sharp endothermic peak of VST was not observed in the thermograms, indicating the absence of recrystallization of the drug after 6 months of storage. Judging from the absence of recrystallization (after 6 months) in the thermograms of the F1 and F2 formulations, the SD developed in this study seemed to be resembling a solid glassy solution. The molecular dispersion of a drug may be immobilized via its interaction (eg, hydrogen bonding) with SP. It is assumed that the HME process reported herein may contribute to the maintenance of the kinetic stability of amorphous drugs.

In vitro drug release

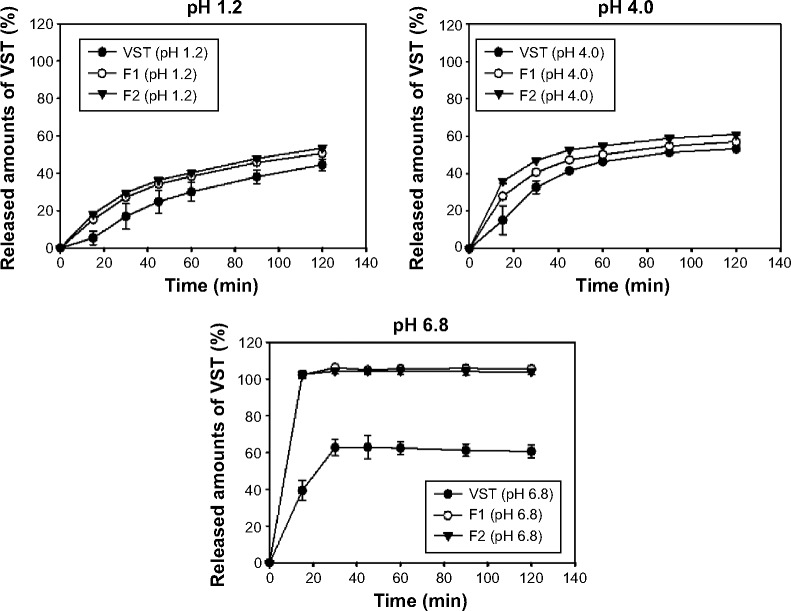

In vitro drug release was assessed at pH values of 1.2 (simulated gastric fluid), 4.0, and 6.8 (simulated intestinal fluid) (Figure 5). Drug release profiles from the SDs (F1 and F2) were compared to the profile of pure VST. As shown in Figure 5, the released amounts of VST from the F1 and F2 preparations were significantly higher than that of the pure drug under all pH conditions. Improved drug release from the SDs developed in this study seems to be related to the low aqueous solubility of VST. VST has low aqueous solubility at low pH values due to its weak acidity.26 Because of the low solubility of VST at pH 1.2 and pH 4.0, 0.3% (w/w) Tween 80 was added to the release media (pH 1.2 and pH 4.0). VST solubility at pH 1.2 and pH 4.0 in media containing 0.3% Tween 80 was 0.41±0.05 and 0.94±0.01 mg/mL, respectively; thus, the sink condition seemed to be maintained during the drug release test. Solubility of VST at pH 6.8 was 9.60±0.42 mg/mL in this study; therefore, solubilizers were not added to these release media to maintain sink condition. Due to the pH-dependent solubility of VST, the amount of drug released at pH 6.8 was greater than that released at pH 1.2 and pH 4.0. Notably, in the pH 6.8 medium, drug release from F1 and F2 reached nearly 100% within 15 minutes. Thus, fast and complete drug release from the developed SD formulations was observed in comparison to pure VST at pH 6.8. Considering that the primary site of drug absorption is usually the small intestine, the improved drug release from the developed formulations at pH 6.8, rather than at pH 1.2, could be beneficial. TPGS, only included in F2, did not induce a significant difference in the drug release pattern at all pH values in this investigation. The improved drug release from the developed SDs can be explained by several factors. Drug amorphization may be related to the enhanced release of poorly water-soluble drugs in HME-processed products. Furthermore, SP seems to contribute to the release of drugs from SDs in aqueous environments. As previously reported,10,27 SP enhances the release rate and the released amount of drug from SD formulations. HME process with a high shear stress also provided a more homogeneous SD. Improved drug release can lead to absorption enhancement in the gastrointestinal tract, in the absence of permeability problem.

Figure 5.

In vitro VST release profiles at pH values of 1.2, 4.0, and 6.8.

Note: Each point indicates the mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; min, minutes; VST, valsartan.

In vivo pharmacokinetic studies

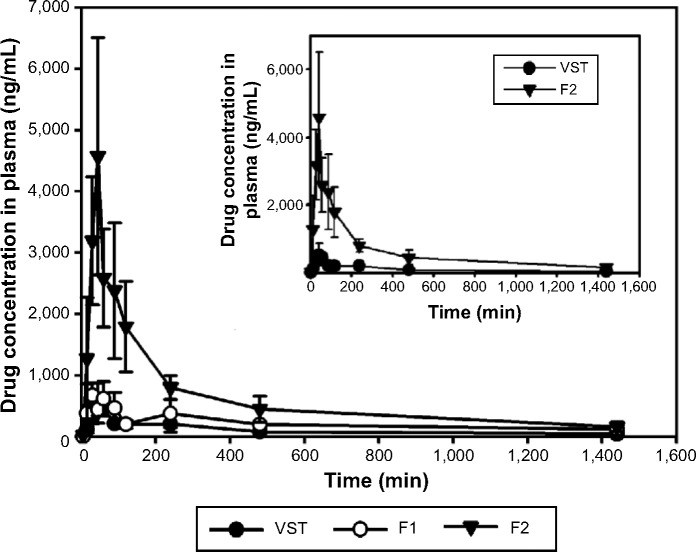

Oral absorption of VST from the developed SDs was assessed in rats. In this study, pure VST, F1, and F2 were administered orally to rats at 4 mg/kg. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 6, AUC values were ranked from lowest to highest as follows: VST<F1<F2. The F2 group showed 5.49- and 1.91-fold higher AUC values, respectively, than the pure VST and F1 groups (P<0.05). Compared to the VST and the F1 groups, the Cmax value of the F2 group was 6.56- and 5.62-fold higher, respectively (P<0.05). No significant differences in Tmax values were detected among the groups. The AUC values in this study indicate that SP enhanced drug absorption. Due to its solubilizing capacity, SP enhances the absorption of orally administered drugs.11 The enhancement of the oral bioavail-ability of drugs seems to be based on the in vivo interaction of the drug, SP, and the intestinal fluid, which contains bile salts and phospholipids that act as sources of micelles.11 TPGS, included in the F2 preparation, also significantly improved the relative oral bioavailability of the drug in this investigation. Although TPGS did not produce different drug release patterns (Figure 5), it contributed to an increase in oral drug absorption. As a plasticizer, TPGS can reduce process temperature and melt viscosity during the HME process. The ability of TPGS to enhance drug permeation in transmucosal drug delivery has already been reported.28–31 The feasibility of VST as a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate was reported earlier;32,33 thus, P-gp can act as a barrier for the intestinal absorption of VST. TPGS, as one of P-gp inhibitors, can improve the oral absorption of VST.30,34 Conclusively, improvement of drug absorption in this study can be explained by the amorphization of the drug, increased drug dissolution, and enhanced drug penetration across the mucosal membrane in the presence of surfactant (ie, TPGS). The absorbed fraction of the VST dose in humans ranged from 23% (for capsules) to 39% (for solutions), and considerable individual variability in AUC and Cmax values has been reported.26 With the reported oral dosage forms of VST,14–16,35–39 SD formulation with HME processing could produce higher oral bioavailability of VST with lower variability among subjects, as compared to the bioavailability of the pure drug.

Table 3.

In vivo pharmacokinetic parameters of VST in rats after oral administration at a dose of 4 mg/kg

| Parameter | VST (n=3) | F1 (n=3) | F2 (n=4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (μg⋅min/mL) | 168.10±28.88 | 482.99±184.77 | 922.89±163.06#,+ |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 0.72±0.28 | 0.84±0.07 | 4.72±1.72#,+ |

| Tmax (min) | 60 (45–60) | 30 (15–60) | 45 (30–45) |

| Relative bioavailability (%) | 100 | 287 | 549 |

Notes: Data are presented as means ± standard deviation, except for median (ranges) for Tmax; Tukey’s test was used as a post hoc test for the statistical analysis;

P<0.05, compared to VST group;

P<0.05, compared to F1 group.

Abbreviations: AUC, total area under plasma VST concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity; Cmax, peak plasma concentration; F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; min, minutes; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; VST, valsartan.

Figure 6.

In vivo pharmacokinetic study in rats.

Notes: VST powder, F1, and F2 were administered orally at a dose of 4 mg/kg. Inset indicates pharmacokinetic profiles of VST powder and F2. Each point indicates the mean ± standard deviation (n=3 for VST powder and F1 groups, n=4 for the F2 group).

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; min, minutes; VST, valsartan.

Histological assays

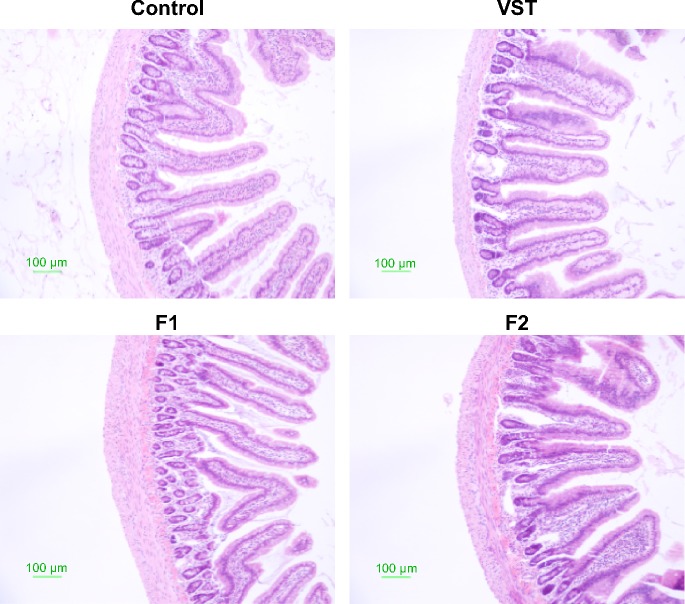

Histological evaluation of the intestinal epithelium was performed in rats after the administration of pure drug and the formulations F1 and F2. The toxicity of the treatment drugs to the jejunum epithelium was assessed by H&E staining (Figure 7). The epithelium, mucosal structures, microvilli, and junctions in the control group were normal and showed no symptoms of inflammation. No significant pathological changes were observed in the groups treated with VST, F1, and F2, as compared to the control group. Negligible inflammation and erosion were detected in the F1- and F2-treated groups. These results exhibit that SD formulations processed by HME methods have no significant toxicity to the intestinal epithelium.

Figure 7.

Toxicity test in the intestinal epithelium observed by H&E staining.

Notes: Jejunum of rat was excised 24 hours after administering each drug or formulation orally. The length of scale bar is 100 μm. A representative image among the replicated samples of each group is shown (n=3 for VST powder and F1 groups, n=4 for the F2 group).

Abbreviations: F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; VST, valsartan.

SP is a grafted copolymer composed of PEG 6000, vinylcaprolactam, and vinyl acetate. According to the manufacturer data (BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany), the oral and dermal median lethal dose (lethal dose, 50%; LD50) values of SP, which are indicators of acute toxicity, were both >5 g/kg. Given the VST dose (4 mg/kg) and formulation composition in this study, oral administration of the developed formulations was not expected to produce serious toxicity. However, the toxicity of SP against tissues and organs, as well as its hematocompatibility, should be further investigated. TPGS, alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) grafted with a PEG oligomer via a succinate diester linker, is known as a generally regarded as safe (GRAS) material. It was reported that a chronic oral TPGS dose of 15–25 IU/kg/day did not produce clinical or biochemical signs of gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, or hematological toxicity.40 Moreover, TPGS1000 was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a solubilizer for parenteral, oral, nasal, topical, rectal, and vaginal drug delivery.41 We have also reported on the good safety profile of TPGS in the gastrointestinal tract in a previous study.1 Taken together, our results show that SP and TPGS-based SD formulations can be used as biocompatible oral drug delivery vehicles.

Conclusion

VST-loaded oral SDs based on SP and TPGS were prepared using the HME process. An HME system with twin screws for inducing a high shear rate was adopted for providing drug amorphization and its molecular dispersion in the polymer matrix. Drug amorphization and related thermodynamic properties of the prepared formulations were investigated by FT-IR, XRD, and DSC. Drug release from the formulations was improved as compared to the level of pure drug, and enhanced drug release was observed at pH 6.8 (simulated intestinal fluid) in comparison to that at pH 1.2 (simulated gastric fluid) and pH 4.0. The oral bioavailability of VST from the developed formulations was improved in rats as compared to that of the pure drug. H&E staining of the intestinal epithelium after oral administration of the prepared SDs indicated their biocompatibility. SP and TPGS-based SDs, manufactured by the HME process with a high shear, can be used to improve the oral bioavailability of drugs.

Supplementary material

DSC thermograms of F1 (6 months) and F2 (6 months).

Abbreviations: DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by 2014 Research Grant from Kangwon National University (120140432) and a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of the Korean government (2009-0083533).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Cho HJ, Park JW, Yoon IS, Kim DD. Surface-modified solid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery of docetaxel: enhanced intestinal absorption and lymphatic uptake. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:495–504. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S56648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JE, Yoon IS, Cho HJ, Kim DH, Choi YH, Kim DD. Emulsion-based colloidal nanosystems for oral delivery of doxorubicin: improved intestinal paracellular absorption and alleviated cardiotoxicity. Int J Pharm. 2014;464(1–2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin YM, Cui FD, Mu CF, et al. Docetaxel microemulsion for enhanced oral bioavailability: preparation and in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Control Release. 2009;140(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baek HH, Kim DH, Kwon SY, et al. Development of novel ibuprofen-loaded solid dispersion with enhanced bioavailability using cycloamylose. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35(4):683–689. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SA, Kim SW, Choi HK, Han HK. Enhanced systemic exposure of saquinavir via the concomitant use of curcumin-loaded solid dispersion in rats. Int J Pharm. 2013;49(5):800–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alam MA, Ali R, Al-Jenoobi FI, Al-Mohizea AM. Solid dispersions: a strategy for poorly aqueous soluble drugs and technology updates. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9(11):1419–1440. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.732064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakshman JP, Cao Y, Kowalski J, Serajuddin AT. Application of melt extrusion in the development of a physically and chemically stable high-energy amorphous solid dispersion of a poorly water-soluble drug. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(6):994–1002. doi: 10.1021/mp8001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djuris J, Nikolakakis I, Ibric S, Djuric Z, Kachrimanis K. Preparation of carbamazepine-Soluplus solid dispersions by hot-melt extrusion, and prediction of drug-polymer miscibility by thermodynamic model fitting. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;84(1):228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leuner C, Dressman J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Z, Lu M, Li Y, et al. The utilization of drug-polymer interactions for improving the chemical stability of hot-melt extruded solid dispersions. J Pharm Pharmcol. 2014;66(2):285–296. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linn M, Collnot EM, Djuric D, et al. Soluplus® as an effective absorption enhancer of poorly soluble drugs in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;45(3):336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin SC, Kim J. Physicochemical characterization of solid dispersion of furosemide with TPGS. Int J Pharm. 2003;251(1–2):79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Eerdenbrugh B, Van Speybroeck M, Mols R, et al. Itraconazole/TPGS/Aerosil200 solid dispersions: characterization, physical stability and in vivo performance. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;38(3):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao QR, Liu Y, Xu WJ, Lee BJ, Yang M, Cui JH. Enhanced oral bioavailability of novel mucoadhesive pellets containing valsartan prepared by a dry powder-coating technique. Int J Pharm. 2012;434(1–2):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beg S, Swain S, Singh HP, Patra ChN, Rao ME. Development, optimization, and characterization of solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems of valsartan using porous carriers. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2012;13(4):1416–1427. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9865-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li DX, Yan YD, Oh DH, et al. Development of valsartan-loaded gelatin microcapsule without crystal change using hydroxypropylmethylcellulose as a stabilizer. Drug Deliv. 2010;17(5):322–329. doi: 10.3109/10717541003717031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan YD, Sung JH, Kim KK, et al. Novel valsartan-loaded solid dispersion with enhanced bioavailability and no crystalline changes. Int J Pharm. 2012;422(1–2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowley MM, Zhang F, Repka MA, et al. Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: part I. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2007;33(9):909–926. doi: 10.1080/03639040701498759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aharoni SM. Increased glass transition temperature in motionally constrained semicrystalline polymers. Polym Adv Technol. 1998;9(3):169–201. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamichi K, Nakano T, Yasuura H, Izumi S, Kawashima Y. The role of the kneading paddle and the effects of screw revolution speed and water content on the preparation of solid dispersions using a twin-screw extruder. Int J Pharm. 2002;241(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tran TT, Tran PH, Park JB, Lee BJ. Effects of solvents and crystallization conditions on the polymorphic behaviors and dissolution rates of valsartan. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35(7):1223–1230. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughey JR, Keen JM, Miller DA, Kolter K, Langley N, McGinity JW. The use of inorganic salts to improve the dissolution characteristics of tablets containing Soluplus®-based solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;48(4–5):758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mu L, Feng SS. A novel controlled release formulation for the anticancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol): PLGA nanoparticles containing vitamin E TPGS. J Control Release. 2003;86(1):33–48. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhugra C, Pikal MJ. Role of thermodynamic, molecular, and kinetic factors in crystallization from the amorphous state. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(4):1329–1349. doi: 10.1002/jps.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu L. Amorphous pharmaceutical solids: preparation, characterization and stabilization. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;48(1):27–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flesch G, Muller P, Lloyd P. Absolute bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/s002280050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pina MF, Zhao M, Pinto JF, Sousa JJ, Craig DQ. The influence of drug physical state on the dissolution enhancement of solid dispersions prepared via hot-melt extrusion: a case study using olanzapine. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103(4):1214–1223. doi: 10.1002/jps.23894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Miao YQ, Fan DJ, et al. Bioavailability study of berberine and the enhancing effects of TPGS on intestinal absorption in rats. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2011;12(2):705–711. doi: 10.1208/s12249-011-9632-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho HJ, Balakrishnan P, Chung SJ, Shim CK, Kim DD. Evaluation of protein stability and in vitro permeation of lyophilized polysaccharides-based microparticles for intranasal protein delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011;416(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, Luo J, Tan S, Otieno BO, Zhang Z. The applications of vitamin E TPGS in drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;49(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varma MV, Panchagnula R. Enhanced oral paclitaxel absorption with vitamin E-TPGS: effect on solubility and permeability in vitro, in situ and in vivo. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;25(4–5):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Challa VR, Babu PR, Challa SR, Johnson B, Maheswari C. Pharma-cokinetic interaction study between quercetin and valsartan in rats and in vitro models. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013;39(6):865–872. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2012.693502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin X, Skolnik S, Chen X, Wang J. Attenuation of intestinal absorption by major efflux transporters: quantitative tools and strategies using a Caco-2 model. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39(2):265–274. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.034629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Tan S, Feng SS. Vitamin E TPGS as a molecular biomaterial for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33(19):4889–4906. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poudel BK, Marasini N, Tran TH, Choi HG, Yong CS, Kim JO. Formulation, characterization and optimization of valsartan self-microemulsifying drug delivery system using statistical design of experiment. Chem Pharm Bull. 2012;60(11):1409–1418. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c12-00502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh SK, Vuddanda PR, Singh S, Srivastava AK. A comparison between use of spray and freeze drying techniques for preparation of solid self-microemulsifying formulation of valsartan and in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:909045. doi: 10.1155/2013/909045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Che E, Zhang M, et al. Increasing the dissolution rate and oral bioavailability of the poorly water-soluble drug valsartan using novel hierarchical porous carbon monoliths. Int J Pharm. 2014;473(1–2):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim MS, Baek IH. Fabrication and evaluation of valsartan-polymer-surfactant composite nanoparticles by using the supercritical antisolvent process. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:5167–5176. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S71891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma Q, Sun H, Che E, et al. Uniform nano-sized valsartan for dissolution and bioavailability enhancement: influence of particle size and crystalline state. Int J Pharm. 2013;441(1–2):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sokol RJ, Heubi JE, Butler-Simon N, McClung HJ, Lilly JR, Silverman A. Treatment of vitamin E deficiency during chronic childhood cholestasis with oral d-alpha-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol-1000 succinate. Gastroenterology. 1987;93(5):975–985. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Constantinides PP, Han J, Davis SS. Advances in the use of tocols as drug delivery vehicles. Pharm Res. 2006;23(2):243–255. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DSC thermograms of F1 (6 months) and F2 (6 months).

Abbreviations: DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; F1 and F2, solid dispersion formulations used in this study.