Abstract

African American women in urban, high poverty neighborhoods have high rates of smoking, difficulties with quitting, and disproportionate tobacco-related health disparities. Prior research utilizing conventional “outsider driven” interventions targeted to individuals has failed to show effective cessation outcomes. This paper describes the application of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework to inform a culturally situated, ecological based, multi-level tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. The CBPR framework encompasses problem identification, planning and feasibility/pilot testing, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination. There have been multiple partners in this process including public housing residents, housing authority administrators, community health workers, tenant associations, and academic investigators. The advisory process has evolved from an initial small steering group to our current institutional community advisory boards. Our decade-long CBPR journey produced design innovations, promising preliminary outcomes, and a full-scaled implementation study in two states. Challenges include sustaining engagement with evolving study partners, maintaining equity and power in the partnerships, and long-term sustainability of the intervention. Implications include applicability of the framework with other CBPR partnerships, especially scaling up evolutionary grassroots involvement to multi-regional partnerships.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, Partnerships, Smoking cessation, Multi-level interventions, RCT

African American (AA) women in public housing neighborhoods face unique barriers to tobacco cessation including social norms for smoking, access to financial and health resources, and lack of socio-culturally relevant quit information (Andrews 2004; Grady et al. 1998; Manfredi et al. 1992). Women in public housing want to quit smoking (Grady et al. 1998; Manfredi et al. 1992) and 50–60% make serious quit attempts each year (Andrews 2004). Traditional mainstream smoking cessation programs, which target strategies at the individual level, have failed to reach or impact smokers in urban, high poverty, segregated neighborhoods (Ahluwalia et al. 2006; Fiore et al. 2008).

In the field of community psychology, experts posit that preventive interventions should engage and influence subcultural community groups; embody cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions; and utilize community initiated indigenous approaches (Barrera et al. 2011). In order to impact health, community prevention interventions should incorporate local culture as a central component in an attempt to understand context of communities, as well as reflect on the culture of which academic investigators go about trying to understand and be helpful in communities (Trickett 2011). An emerging scientific paradigm supports collaborative, culturally situated, and ecological based community interventions aimed at creating sustainable community-level impact (Trickett et al. 2011). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches promote collaborative and equitable relationships between academic investigators and community partners, as well as both culturally and contextually situated intervention development, implementation, and community capacity building processes and outcomes (Trickett et al. 2011).

The purpose of this paper is to describe the application of a community based participatory research (CBPR) framework to inform a culturally situated, multi-level, ecological based tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. Community and academic partners used this framework to guide problem identification, planning and feasibility testing, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of this intervention. The application of CBPR to each phase is briefly summarized, with an extensive description of the current randomized controlled trial (RCT). Successes and challenges of the prevention intervention and partnership are discussed, including sustainability of both.

Background

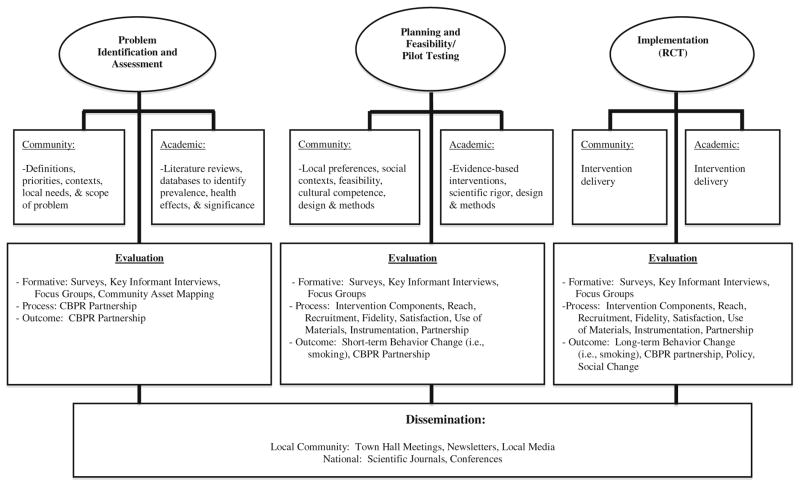

Partnership Formation

Our “Sister to Sister” journey began over a decade ago with a phone call from an inner-city school counselor to the first author (JA). The counselor learned of JA’s leadership with tobacco cessation efforts in a local hospital through a feature story in the local newspaper. The two met to discuss working together to address the community’s high smoking rates and subsequent social and health effects among families living in the school’s high poverty, segregated neighborhoods. A series of meetings led to the formation of a five-member steering committee (e.g., school officials, local residents, and academic investigator) to provide recommendations on how to address the significant tobacco use problem in the community. We embraced a participatory process, and over time, adapted a CBPR framework to guide our approach as depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CBPR framework to inform RCT

Problem Identification and Assessment

Guiding principles of CBPR acknowledge that both academic and community partners have expertise and are co-learners (Minkler 2005). During our problem identification and assessment phase (see Fig. 1), the community partners contributed expertise on local priorities and needs, and provided the local context for tobacco use. For example, cigarettes are legal, highly accessible (either from “bumming off others, buying loosies, or local convenient stores), and are used to cope with daily hassles and struggles. The academic partners contributed evidence from the literature and existing databases on the prevalence of tobacco use and the impact on tobacco-related health outcomes.

Our steering committee agreed to conduct a multi-faceted community assessment on smoking behaviors, environmental contexts, and interest in taking action. Methods for evaluation included community asset mapping, windshield tours, quantitative neighborhood survey, and a grounded theory study, which are described in more detail elsewhere (Andrews 2004; Andrews et al. 2007a). A summary of our assessment is provided in Table 1. We disseminated the findings via two town hall forums in surrounding public housing neighborhoods. Based on the high rates of smoking and interest in cessation, we reached consensus to pursue planning for a cessation intervention for women living in surrounding public housing neighborhoods.

Table 1.

Summary of problem identification and recommendations for a multi-level intervention

| Methods | Community (preferences) | Academic (evidence-based literature) |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Problem identification and assessment | ||

| Windshield tours/asset mapping | Physical infrastructure of the neighborhoods reveal densely populated (i.e., 150 units on 4 acres of property) single or multi-level housing units; cemented streets and parking areas with limited or no green space; units with cracked windows and doors; occasional boarded up empty units embellished with graffiti; patrolling police cars; and, convenience stores fronting these developments with iron bars covering the windows | The ecological perspective focuses on the nature of people’s transactions with their physical and socio-cultural surroundings (Glanz et al. 2008) |

| Social infrastructure reveals extensive social networks; residents share common outdoor space, lifestyle behaviors (i.e., cigarette smoking), tangible products (i.e., cigarettes), and information. Smoking is a shared, communal behavior in these neighborhoods | Recognize and begin assessment with community strengths and assets. By involving community members in visual, intuitive, and processes of self-assessment and discovery, assets-oriented approaches invite more creativity in assessment and planning (Minkler 2005) | |

| Women leaders available who assist other women with childcare, cooking, other supportive needs. Interest to improve community’s overall quality of life for self and families. Agree that addressing smoking is a priority issue for community | The key to neighbourhood regeneration, even among the most urban and poor neighborhoods, are to locate assets and begin connecting them in ways to multiply their power and e effectiveness (Kretzmann and McKnight 2003) | |

| Neighborhood survey (20% of female head of households; n = 220) | Forty percent (n = 88) of the women surveyed were current smokers and 48% (n = 106) of the households had at least one smoker in the residence | The prevalence rate of smoking in AA women residing in US public housing neighborhoods is reported to be as high as 40–60% (Grady et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2007) |

| Sixty-two percent of the women who smoked (n = 55) indicated they were interested in quitting in the next 6 months | Women in public housing want to quit smoking (Grady et al. 1998; Manfredi et al. 1992) | |

| 50–60% of smokers make serious quit attempts each year (Fiore et al. 2008) | ||

| Grounded Theory Study (n = 25 AA female former smokers) | The transition of smoking to cessation is viewed as an empowerment process that occurs from self-awareness, self-commitment, liberation, and use of personal and spiritual resources | AA women from the community who have quit smoking are empowered experts and potential CHWs to assist peers (Andrews et al. 2004) |

| Spirituality is a major component of sustaining this change and is embedded in the context of their physical, social, and psychological well-being | Spirituality is a preferred coping strategy to assist with the cessation process (Lacey et al. 1992) | |

| Phase II: Recommendations and planning for tobacco cessation intervention | ||

| Key informant interviews (n = 30) | Prefer approach with multiple strategies involving multiple levels of influence | Ecological levels of influence on behavior include individual factors (e.g., knowledge, behavior), interpersonal networks (e.g., family, friends, peers), community factors (e.g., relationships among networks) (McLeroy et al. 1988; Stokols 1996) |

| Neighborhood forums × 4 | Testimonials from AA women who had quit smoking | Indigenous community health workers (CHWs) (i.e., members from the community who share the same language, culture, attitudes, and beliefs) can be effective role models for AA women to adopt healthy (Andrews et al. 2004) |

| Peer group meetings (women only) with food to provide support for those who wanted to quit smoking | A mechanism known as “sister circles” is often enhanced in organized group sessions with homogenous AA women. Sister circles are groups of women with common bonds that provide vital information, psychosocial and spiritual support, and mentoring to their members (Baldwin 1996) | |

| Involvement of neighborhood leaders to implement change at the neighborhood level | A neighborhood-based governance board is effective in delivering counter-marketing and support strategies to reduce smoking prevalence among AA communities (Fisher et al. 1998) | |

| Presentation of the cessation information in a format that women could understand, related to, and that incorporated the context of their life experiences | Tobacco-dependent AA women prefer group cessation programs that are nonjudgmental and accessible, promote support and understanding of their situations, and offer strategies to cope with their lives (Webb 2008) | |

| Incorporate evidence from research | The US Public Health Service (PHS) Treating Tobacco Dependence Use and Dependence Guideline (Fiore et al. 2008) recommends: (1) four to seven sessions that are 20–30 min in length over a minimum of a 2 week period; (2) individual or group counselling with problem solving and skill training; (3) provision of social support; (4) relapse intervention; (5) pharmacotherapeutics (i.e., nicotine replacement); and, (6) tailored cessation programs for ethnic groups | |

Planning and Feasibility/Pilot Studies

Our planning phase of CBPR incorporated cultural preferences, social contexts, and perspectives of feasibility from the community members. The academic investigators contributed knowledge of evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions and expertise with research methodologies and designs. Formative data (key informant interviews, neighborhood forums) collected in this planning phase are summarized in Table 1. Our steering committee formalized into an eight-member community advisory board (CAB), consisting of two public housing residents, two housing authority administrators, church pastor, school official, health department staff member, and an academic investigator.

The CAB named the project (Sister to Sister: Women Helping Women to Quit Smoking), and co-developed the cessation materials and intervention protocols for a feasibility study (n = 10 AA female smokers). The purpose of the study was to test the feasibility of participant recruitment and two intervention components: peer-groups led by a smoking cessation specialist; and individual level interactions with community health workers (CHWs). A larger pilot study (n = 103 AA female smokers) followed, testing the effect of a multi-level intervention (neighborhood, peer-group, and individual) in two public housing neighborhoods and is described elsewhere (Andrews et al. 2005, 2007b). We disseminated these findings to the community via neighborhood forums, newsletters, and the local newspaper. Process and outcome data revealed multiple lessons learned that guided the development of the current multi-level intervention and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Process and outcome evaluation from preliminary studies that guided multi-level intervention considerations

| Process evaluation | |

| Design considerations | Cluster design will be needed, with randomization by neighborhood, due to preferred neighborhood level strategies as part of bundled intervention component |

| Community prefers a control condition with useful materials to aid smoking during intervention phase, with a delayed intervention after study completed similar to treatment intervention | |

| Intervention components: Individual level strategies [community health workers (CHW)] | Preferred by women as delivery mechanism; use term “coach” in field instead of CHW |

| Effective in 1:1 interactions to enhance self-efficacy and spiritual well being | |

| Exceptional navigation skills; understands social/environmental context | |

| Not effective in leading groups of peers | |

| Identification, hiring, training and supervision processes have been defined | |

| Refinement of protocols with structured interview guides | |

| Recommended weekly interaction for 12 weeks with graduated termination plan over following 12 weeks | |

| Intervention components: peer group level strategies | Preferred by women to meet in small groups (8–12) |

| Means of social support for women | |

| Women will participate: 70% attended at least 75% of the group sessions offered | |

| Reminders are needed 24 h prior to group session (phone call, post card, and/or visit) | |

| Late afternoon or evening hours preferred; offer childcare | |

| Nurse cessation specialists are effective in facilitating group cessation counselling | |

| Allow time for storytelling among women (sharing of experiences) | |

| Food and door prizes at meetings preferred | |

| Group prayers (in large circle) preferred at end of each session | |

| Locally developed training manual and participant manual refined | |

| Intervention components: neighborhood level strategies | Identification and training neighborhood advisory boards have been defined |

| Neighborhood leaders are willing to serve; small honorarium preferred | |

| Research staff and advisory board can work together, establish realistic goals, and pool resources | |

| Innovative in approaches (message board at entry to community for neighbourhood communication) | |

| Use neighborhood “block” communication channels, bingo games, fish fry to disseminate information | |

| Intervention components: nicotine replacement therapy | Acceptability (67% participants used at least 4 weeks) |

| Use of over-the-counter product may allow sustainability of translating the intervention in a “real world” setting | |

| Administration and monitoring processes have been defined | |

| No serious adverse events (expected occurrences of minor itching, site irritation, vivid dreams for small percentage of sample) | |

| Socio-cultural tailoring | Locally developed written materials at 3rd–4th grade; large white space; large font; photos/graphics of familiar “real” women that give meaning to text (i.e., Sister Handbook) |

| Spiritual context preferred in written materials and verbal interactions | |

| Prayer (CHWs, group meetings, neighborhood meetings) | |

| Collectivism (setting group goals; disseminating information to entire neighborhood for everyone to benefit) | |

| Use of CHWs and neighborhood advisory board (familiarity, knowledgeable of preferences, navigation) | |

| Use of storytelling in groups | |

| Kinships (mothers, daughters, sisters often live in same neighborhood and supportive) | |

| Reach | Neighborhood level strategies provided reach to all participants (neighborhood signs, material dissemination to each household) |

| Enrolled approximately 70% of women who smoke in each neighbourhood | |

| Recruitment | 100% recruitment goals obtained for each neighbourhood |

| 88–92% and 85–88% retention at 6 and 12 months | |

| Effective strategies employ key influential residents to assist with “word of mouth”, flyer distribution | |

| Information sessions with food in community center | |

| Instrumentation | Salivary cotinine collection and shipping materials developed; acceptable to participants (no participant has refused collection) |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) effective for initial screening; acceptable to participants | |

| Instrumentation for self-efficacy, social support, nicotine dependence, depression acceptable | |

| Need to revise/adapt spirituality and stress instrumentation to more adequately reflect population | |

| Need additional neighborhood level measures (neighborhood stress, neighborhood cohesion) | |

| Fidelity | Manuals established; Fidelity observation checklist for CHW, peer group, neighbourhood, written materials, patches implemented |

| Satisfaction | High satisfaction among participants, steering committee, research staff |

| Partnership | Orientation and training manuals needed for new partners and board members |

| Partners change over time (i.e., leave area, change jobs); need multiple relationships within each partnership entity (i.e., academic organization, housing authority officials, resident leaders) | |

| With multi-site trial, will need one comprehensive CAB that views larger scope of project | |

| Relationships are made one at the time; trust building is timely, and not always possible due to history (i.e., history between academic organization and public housing; history between public housing administrators and residents) | |

| Equity and power sharing can be problematic; especially with resource allocation | |

| All partners highly engaged with problem identification and assessment | |

| Academic partners focus/prioritize measurement and evaluation; community partners value dissemination | |

| Partnership readiness varies greatly among neighborhoods | |

| Requires time and trust to identify neighborhood level champions to serve on neighbourhood boards and to lead neighborhood activities | |

| Capacity of board to implement activities is reflective of leadership, history of neighborhood’s implementation of neighborhood activities (i.e., resident participation), history and trust between neighborhood administrative staff and residents, and community cohesion | |

| Outcome evaluation | |

| Cessation outcomes | 7-day point prevalence cessation rates were higher in the intervention group than the comparison group at week 6 (49% vs. 7.6%; OR = 11.5, 95% CI = 3.6–36.8), week 12 (39% vs. 15%; OR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.4–9.1), and at week 24 (39% vs. 11.5%; OR = 4.9, 95% CI = 1.8–13.7). |

| The 6-month prolonged cessation outcomes were 27.5 and 5.7% (OR = 6.2, CI = 1.7–23.1). | |

| CBPR partnership | Core group sustained and empowered to continue. |

| With study expansion to new community, will use existing CAB infrastructures at institution to guide overall study implementation; site-specific neighborhood board to guide treatment neighborhood activities. | |

| View study as useful to community; satisfied with processes. | |

| Neighborhood board in pilot community continued with community level activities after pilot grant ended; formed resident “relief” fund, continues with neighborhood cookouts, and continues “no smoking policy” around children’s events. | |

Implementation of Randomized Controlled Trial

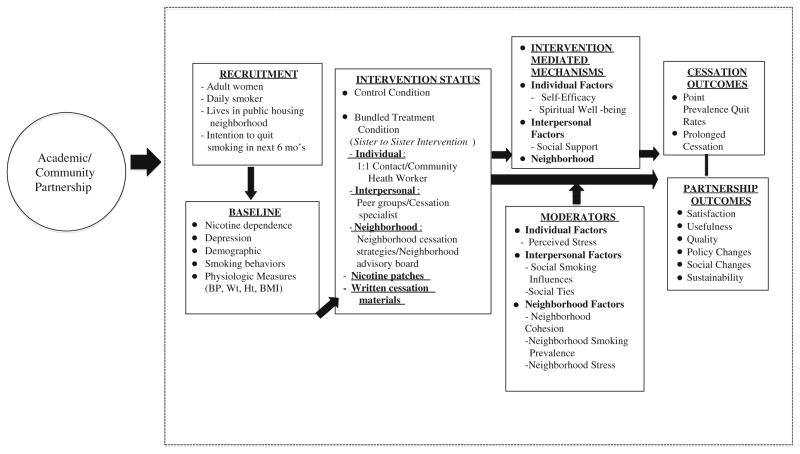

We are currently implementing a randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the effect of the multi-level intervention on cessation outcomes in 14 public housing neighborhoods in two Southeastern US metropolitan communities. The RCT began in December, 2008 and will be completed in December, 2013. The guiding social-ecological based model, including major study variables, is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Guiding social ecological model for multi-level smoking cessation intervention (Sister to Sister)

Three years lapsed from the final pilot study to the implementation of the RCT due to a number of factors: academic investigator assuming new position in a different state; need to establish partners in the new community; need to establish infrastructure for advisory group oversight for both locations; and obtaining funding to implement a larger multi-site trial. The original academic investigator (JA), three community partners, and pilot neighborhoods remained with the evolving project over time. With the changes to scale up the study to two states, we now utilize the two academic institutions’ established CABs to guide the overall implementation of the study.

Design

We use a cluster randomized design in which neighborhood is the unit of randomization and each participant, within neighborhoods, is the unit of measurement. We formed 7 matched pairs of 14 public housing neighborhoods, based on neighborhood size within geographic location, and randomly assigned one neighborhood in each pair to either a multi-level smoking cessation intervention (Sister to Sister) or delayed control condition.

Setting

Fourteen of 30 traditional public housing neighborhoods in these two metropolitan communities met neighborhood inclusion criteria [e.g., family residential neighborhoods, have at least 100 adult female residents, and have not been previously used in our pilot studies]. The 14 neighborhoods are not contiguous and are all located in separate school zones, limiting the risk of contamination across neighborhoods.

Participants

A total of 406 participants are currently being recruited from these 14 public housing neighborhoods (29 women from each neighborhood). Inclusion criteria are: females 18 years and older, current daily smoker, thinking about quitting in next 6 months, and exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) >8 ppm. The exclusion criteria are: pregnant or breast feeding, acute psychiatric disorder, myocardial infarction in the past month, or plans to move in the next 12 months.

At the entry to a new neighborhood, the site’s project team (i.e., principal investigator, study coordinator, CHWs) meets with neighborhood leaders (resident managers and resident groups) to explain the overall study purpose and to obtain informal neighborhood consent. The project team spends several days per week over several weeks to get to know local residents and develop relationships with neighborhood liaisons. These liasons assist the project team to distribute study flyers (dates and times of information sessions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and toll-free phone numbers), and use “word of mouth” to recruit participants for the study.

The project team holds study information sessions with food in the neighborhood activity center to provide a study overview. Interested women are screened for eligibility, consented, enrolled, and baseline data are collected. To accommodate study logistics and to prevent selection bias, each site recruits women simultaneously from two matched pairs of neighborhoods using the same procedures. Once the baseline recruitment is completed, the study statistician notifies the project staff to which condition (i.e., treatment or control) the neighborhood has been randomized. All women enrolled in the study receive a graduated remuneration at the end of each data collection ($25 gift card at baseline and at week 6; $50 gift card at 6 months; $75 gift card at 12 months).

Multi-Level Treatment Intervention (Sister to Sister)

The Sister to Sister Intervention is a 24-week bundled, multi-level intervention that intervenes at the individual, interpersonal, and neighborhood levels.

Individual Level Strategies

Community health workers (i.e., AA women from the community, former smokers, and credible leaders) lead the individual strategies. As we learned from our process data (Table 2), we refer to our CHWs as “coaches” in the field based on preferences of both CHWs and participants. The 1:1 CHW intervention components are initiated in the treatment (TX) neighborhoods within the first week of the 24-week intervention period. Two CHWs are assigned to each TX neighborhood, with 14–15 participants assigned to each CHW. The CHW makes pro-active personal contact with participants using semi-structured guides to assist women in quitting smoking by building confidence in quitting (self-efficacy) and the use of spiritual resources as a coping strategy. These semi-structured guides incorporate the use of the CHWs own language and cultural style, and the opportunity to share testimonials and personal experiences. For example, based on process data with CHWs and cultural preferences (Table 2), CHWs offer to pray with individuals, share bible passages, and cultural poems and inspirational themes. The CHW encourages the participant to set a quit date within the first 2 weeks of the intervention. Based on our experiences and feedback from our pilot studies, the protocols for proactive CHW contacts include weekly contacts for 12 weeks, every other week for 4 weeks, and every 4 weeks for 8 weeks (24 weeks total). All CHWs are employed full-time by the university, receive compensation and benefits, and receive 40 h of training on study protocols.

Interpersonal (Group) Strategies

Behavioral group sessions are led by a certified smoking cessation counselor, who has a minimum of a health professions master’s degree and experience with group cessation counseling. The group sessions are initiated in the TX neighborhoods within the first week of the 24-week intervention period, are offered weekly for 6 weeks, and are based on recommendations from PHS Treating Tobacco Dependence Guideline (Fiore et al. 2008), with adaptations based on the community’s input during our formative work. The adaptations (Table 2) reflect time and location preferences, and socio-cultural preferences including group meetings with food, ethnically appropriate graphics and content, emphasis on stress reduction, spiritual themes and prayers, and opportunities for storytelling. Collectivism preferences are attempted with collective quit dates, small gifts for all who attend (regardless of cessation progress), and pot luck dinners at the last group session.

The group sessions enhance positive social support systems, both intra-treatment-and extra-treatment social support among peers, as recommended by the PHS Guideline (Fiore et al. 2008). To promote social support, the group leader facilitates the delivery of emotional support (i.e., empathetic listening, displaying concern) among peers and assists in identifying other positive support systems within families and/or neighborhood. To promote individual and group interaction, each group is limited to 8–12 participants. Three groups are offered in each TX neighborhood to accommodate the 29 enrolled women, and each group session lasts approximately 1 h. The specific content of each group session is described elsewhere (Andrews 2004; Andrews et al. 2005, 2007a, b).

Neighborhood Level Strategies

A 5-member neighborhood advisory board (NAB) leads the neighborhood level strategies. Within each TX neighborhood, the project team works with neighborhood and housing authority leaders to identify, screen, and recruit adult residents for the appropriate composition of the board (both informal and formal resident leaders, smokers and non-smokers, men and women, and representatives of varying ages). Board members must be a resident of the neighborhood, have a history with assisting with neighborhood events, considered a positive role model, and have interest in collective neighborhood efforts. We hold the first NAB meeting in the TX neighborhoods within the first 2 weeks of the 24-week intervention period. The NAB is responsible for implementing a set of “core” activities including: a neighborhood “kick-off event,” at least two anti-smoking activities, and at least one policy change. Examples of neighborhood anti-smoking activities include: hosting a Smoke-Out Day, anti-tobacco messages from community leaders, community food events with testimonials from former smokers, and distribution of pamphlets/posters on risks of passive smoke exposure to children. Examples of policy activities include setting guidelines about smoking at the community center, prohibiting smoking during children/family events, and allowing “public service housing credit” for participation. In addition, neighborhoods are encouraged to promote the project with announcements on display boards and newsletters. NAB members receive training, project manuals, technical assistance, $500 budget for the events/activities, and a $75 honorarium per member.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

In accordance with the PHS Guideline (Fiore et al. 2008), an 8-week supply of transdermal nicotine patches is offered to each participant at no cost. The patches are administered and monitored weekly following the group sessions by the certified smoking cessation counselor. Participants initiate the nicotine patch on their established quit date (usually set within 2 weeks of the intervention period). The specific nicotine replacement protocols and dosing are described elsewhere (Andrews 2004; Andrews et al. 2005, 2007a, b).

Study Specific Written Cessation Materials

We provide written cessation materials (Sister to Sister handbook) to each TX participant at enrollment. The handbook is written at the 3rd–4th grade reading level and designed to accompany each group session. The materials contain information on principles of addiction, pros and cons of quitting smoking, health risks of smoking, coping strategies, stress reduction, pharmacotherapeutics for cessation, relapse prevention, weight management, nutrition, and physical activity. There are prompts and space to record personal diaries and goal setting, and selected inspirational scripture and poems throughout the handbook. Our initial study CAB and CHWs developed the handbook, with multiple revisions during the formative work based on focus group and process evaluation measures. Further descriptions of the handbook are described elsewhere (Andrews 2004; Andrews et al. 2005, 2007a, b).

Control Condition

Participants in control neighborhoods receive Pathways to Freedom: Winning the Fight Against Tobacco (Centers for Disease Control 2003) at baseline. The manual includes characteristics of smoking among AAs, health risks of smoking, how to quit, coping strategies, and how to sustain cessation. Control participants receive additional materials in the mail at week 6 (State-Sponsored Toll-Free Tobacco Quit Line pamphlet), week 12 [PHS Guideline patient pamphlet (You Can Quit Smoking)], and week 18 [American Cancer Society pamphlet (When Smokers Quit)].

All control participants are offered a delayed intervention at the end of the study (i.e., after the 12 month data collection), based on community preferences (Table 2). This intervention includes a 1-h face-to-face counselling session with the cessation specialist, personal contact by a CHW four times over 8 weeks, and an 8-week supply of nicotine patches.

Evaluation/Dissemination

Evaluation of the RCT is ongoing and consists of outcome evaluation (point prevalence and prolonged smoking abstinence outcomes and partnership outcomes), mediator and moderator analyses, and other variables as outlined in Fig. 2. Saliva cotinine is used to validate self-reported cessation outcomes. Extensive process evaluation includes: (a) the degree to which the intervention components are implemented as planned (fidelity); (b) the dose of each level of the intervention received; (c) reach of the intervention; (d) acceptability of the intervention, and, (e) competing explanations for the results. We conduct partnership and NAB evaluations to assess satisfaction, usefulness, quality, policy changes, social changes, and sustainability.

Dissemination, like evaluation, is ongoing. We disseminate information via neighborhood forums, newsletters, letters to enrolled participants, and local newspapers. Collectively, the NABs, the institutional advisory boards, and the academic partners are involved with the content and delivery of the disseminated materials.

In summary, the academic and community partners, based on problem identification and assessment (Table 1), feasibility pilot testing, and ongoing process and outcome evaluations (Table 2), have carefully constructed the RCT. We have incorporated evidence-based guidelines, socio-cultural preferences, and multiple lessons learned. The CBPR framework (Fig. 1) has been an invaluable blueprint to guide these processes to develop a multi-level intervention, with indigenous CHWs, peer groups, and NABs, and that involves both participants and neighborhood residents with the implementation of the intervention within the context of the neighborhood setting.

Discussion

Compared to traditional research, CBPR frameworks facilitate collaborative, culturally situated, and ecological based community interventions (Trickett et al. 2011).

CBPR offers the potential to improve intervention design and implementation, facilitate participant recruitment and retention, augment the quality and validity of research, and increase the rate of knowledge translation (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research 2011). The ecological and multi-level approach, preferred by the community over a decade ago, is congruent with current academic trends in behavioral theories and research (Glanz et al. 2008). This is the first known CBPR initiated multilevel smoking cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods and attests to the community partners’ expertise in translating evidence-based treatment regimens into their “real world” community setting.

A possible contributor to this partnership’s success so far is the careful attention of the readiness of the partnership at each stage of this journey. Major dimensions of CBPR partnership readiness are goodness of fit, capacity, and operations (Andrews et al. 2010, 2011). The partnership assessed the goodness of fit early in this process to insure shared values, a compatible climate, mutual benefits, and dedicated commitment. Capacity of the partnership evolved over time with each CBPR phase, including leadership, inclusive membership, complementary competencies, and adequate resources. Thirdly, the operations of the partnership to facilitate congruent goals, transparent communication, and conflict resolution evolved with the project, especially with reflective insight on lessons learned along the way (Andrews et al. 2010). Although our team utilizes a CBPR Partnership Readiness toolkit (Andrews et al. 2010) to evaluate readiness as the partnership and intervention evolves, we expect as we scale up the intervention and implementation of the RCT, these readiness dimensions may vary as we engage with new partnerships in new neighborhoods. For example, although all public housing neighborhoods in our RCT appear homogeneous with demographics and physical environments, heterogeneity exists, especially with preferences for a smoking cessation intervention, neighborhood climate, and grass-roots neighborhood leadership. To address this, we have developed extensive orientation and training manuals and visual PowerPoint presentations for new partners. We recognize that we will need to be flexible with our timeline, so that we can adequately build relationships and trust, identify committed leaders within each neighborhood, and learn together how the implementation will best be suited for each neighborhood, while maintaining fidelity and rigor of the intervention. Additional research is needed to understand how to both measure and leverage readiness for multi-site, cluster-designed trials.

Lack of trust is the most frequently mentioned challenge in CBPR partnerships (Israel et al. 1998), and has been a challenge for us as well. Many public housing residents and housing authority administrators have had historical negative relationships with academic institutions, from health care and research perspectives, over many decades. Additionally, unique power and trust issues exist between public housing administrative staff and residents. From the onset, we have spent considerable time on developing relationships, often one person or one small group at a time. Our partnership has attempted open dialogues, transparency, sharing past experiences, and encouraging self-reflection and critique of all members. Exercising the concepts of cultural humility (Tervalon and Murray-Garcia 1998) has been important to establish and maintain trust during this process (Yonas et al. 2006).

Similarly, we struggle with equity and power challenges in our partnership. For example, with the first pilot studies, the steering committee recommended that the housing authority administration receive an allocation of the grant funds to employ the CHWs, provide food for meetings, and incentives for participants. However, the housing authorities understandably did not wish to set precedence for employing community members on short term grant funding or for the issuance of incentives for research participation with concerns that the residents may expect the housing authority to financially incentivize participation for other activities. Since the steering committee did not have the capacity to receive funds, we decided for the academic institution to receive the grant funds, hire the CHWs, and distribute funds to each neighborhood for study related activities. This lack of equity in financial resources leads to potential power imbalances among the partners and continues to be a limitation of our CBPR partnership (Israel et al. 2008).

Another priority challenge for our team is how to achieve sustainability of both the intervention and partnership over time. Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone’s (1998) model of intervention sustainability include: (1) maintaining the health benefits of an intervention over time; (2) institutionalizing an intervention or its components within an organization; and (3) building the capacity of the community involved. We are collecting 12-month cessation outcome data on participants in the RCT, along with process data to evaluate time and potential reasons for relapse to better understand cessation patterns with women in our study. We address intervention sustainability by hiring, and promoting capacity of indigenous CHWs, with the intent they will continue encouraging health-promoting behaviors beyond this particular study. To evaluate our progress with institutionalization, we conducted a phone survey with pilot participants 3 years after the pilot study ended, and learned that at least one-third of our participants have attempted to help other friends and family members quit smoking.

We invest in empowerment processes and capacity building with the neighborhood leaders (i.e., with training and modelling behaviors on the NAB and enrolled residents (i.e., within group and CHW sessions) to continue their successes. For example, we attempt to build capacity for each NAB by providing mentorship on fund-raising, seeking donations from local vendors, and fiscal accounting and management (i.e., establishing banking accounts, obtaining 501(c)3 status). A 3-year post assessment of our pilot treatment’s NAB revealed that they: continue to meet several times a year; have established a resident relief fund for residents who are in crisis and may need financial assistance (i.e., with power bills); continue with neighborhood cookouts; and continue with their neighborhood message board at the entrance to community to highlight upcoming events and special achievements among residents. Our advisory board provides links to additional partners (i.e., churches, schools, public health officials) to continue the progress with health promoting activities in these neighbourhoods. A local church has now adopted our pilot neighborhood and its’ members have become involved with volunteer work and various other recurring programs. The academic partners also facilitate educational offerings on other health topics, and involve students and other faculty with other health prevention projects or activities in these neighborhoods.

To sustain the partnership over time, Israel et al. (2006) posit the following dimensions: (1) sustaining relationships and commitments among the partners involved; (2) sustaining the knowledge, capacity and values generated from the partnership; and (3) sustaining funding, staff, programs, policy changes and the partnership itself. Continuing the engagement and sustaining the partnership over time has been a challenge for our team, as well as others (Israel et al. 2006). For example, during the 8-year time period from the initial partnership to the implementation of the RCT several key personnel changes occurred. Several partners relocated, changed jobs, or exited due to lack of time or commitment. We now address partnership infrastructure needs by having “champions” at multiple levels within each entity (academic, housing authority administration, and neighborhood leaders; Andrews et al. 2010; Israel et al. 2006). This approach is helpful in that if one member exits, we continue to have other identified champions within that partnership entity to continue our progress. The recognition and continued building on partners contributions, knowledge, and skills will continue to enhance the overall quality, appropriateness, and sustainability of the partnership (Israel et al. 2006). We frequently reflect on our knowledge gained with our partnership, and the dissemination of our work, such as this collaborative publication, aids this process.

We also found that, over time, having a more centralized institutional advisory board has been effective in guiding the overall broader vision and mission of the multi-site project (Newman et al. 2011). However, community partners continually state the need for NABs to guide their neighborhood level intervention activities based on their unique culture, informal leadership structures, and preferences.

With funding resources, we now provide compensation to both our CAB and NAB members for their time and participation with the respective boards. We have developed memorandum of understandings with each housing authority and written contracts with each board member, in an effort to formalize the relationship and build value for the respective service. We have collectively established guiding principles for our partnership (Newman et al. 2011) and disseminate to all new members. We will assess if the formalization of these processes, also recommended by others (Israel et al. 2006), assists our partnership sustainability over time.

Sustaining funding is especially problematic during these economic times, and we have had two lapses in funding over the past decade, with the largest lapse over 2 years. The current grant is 5 years, with time to plan and submit for other funding for staff and other health prevention programs. Our partnership is currently in the planning processes for another community preferred weight loss intervention within these neighborhoods. We have been creative with funding, and often use other grant and other available resources to supplement staff or community partners’ time and contributions.

Finally, community prevention interventions designed for cultural subgroups are complex interactions, expensive, and challenging. In promoting future agendas with CBPR developed prevention interventions, Trickett et al. (2011) recommend RCTs adapting to context and culture while retaining the merits of comparability to a comparison group. This adaptability allows variation across multiple sites without threatening the fidelity or integrity of an intervention (Trickett et al. 2011). While we are attempting to accomplish this with our current RCT, this science is still in its infancy, and additional research is needed. For example, we are currently in the process of attempting to understand how to scale up an intervention developed with a discreet cultural subgroup (AA women in public housing) and a specific grassroots regional partnership (i.e., local housing authority), to a multi-site, multi-state partnership and intervention implementation. While demographically the intervention sites appear homogenous, social heterogeneity exists, including interests in the behavior change, neighborhood cohesion, prior historical relationships (with academics, housing authorities, and residents), and varying neighborhood level leadership among sites. Further research is also needed that guides understanding of the best processes and practices for long-term sustainability of both the intervention and partnership, especially when the RCT is complete.

Conclusions

The application of a CBPR framework has empowered community members, whose input has been previously ignored, as partners in the planning, design, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of the Sister to Sister intervention. The community and academic partners have demonstrated a sustained relationship, created mutual learning experiences, and have identified a preferred and feasible approach to address a common interest and national health priority. Lessons learned about the evolution of multi-regional partnerships with grassroots organizations (i.e., neighborhood residents), government-led organizations (housing authorities), and academic institutions may be valuable to other CBPR partnerships considering this journey.

Acknowledgments

This study received funding/support from: National Institutes of Health/National Heart Lung & Blood Institute, 5R01HL090951-03. South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, Medical University of South Carolina’s CTSA, NIH/NCRR Grant Number UL1RR029882. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCRR.” The authors wish to thank Dr. Mary Ellen Wewers, Ashley Stevenson, Kendra Piper, Kelora Myles, Tammy McCottry Brown, Sheree Cartee, Matthew Humpries, Toni Ravenell, Erin Crawford, Augusta Housing Authority, Aiken Housing Authority, Charleston County Housing Authority, Housing Authority for the City of Charleston, and North Charleston Housing Authority for their contributions to this project.

Contributor Information

Jeannette O. Andrews, Email: andrewj@musc.edu, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, 99 Jonathon Lucas Street, MSC 160, Charleston, SC 29426-1600, USA

Martha S. Tingen, Child Health Discovery Institute, Georgia Health Sciences, University, Augusta, GA, USA. Georgia Prevention Institute, Georgia Health Sciences, University, Augusta, GA, USA

Stacey Crawford Jarriel, Sister to Sister, Augusta, GA, USA.

Maudesta Caleb, Sister to Sister, Augusta, GA, USA.

Alisha Simmons, Sister to Sister, Charleston, SC, USA.

Juanita Brunson, Sister to Sister, Charleston, SC, USA.

Martina Mueller, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, 99 Jonathon Lucas Street, MSC 160, Charleston, SC 29426-1600, USA.

Jasjit S. Ahluwalia, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Susan D. Newman, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, 99 Jonathon Lucas Street, MSC 160, Charleston, SC 29426-1600, USA

Melissa J. Cox, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, 99 Jonathon Lucas Street, MSC 160, Charleston, SC 29426-1600, USA

Gayenell Magwood, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, 99 Jonathon Lucas Street, MSC 160, Charleston, SC 29426-1600, USA.

Christina Hurman, Sister to Sister, Charleston, SC, USA.

References

- Ahluwalia J, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, Choi W, Kaur H, Pulvers K, et al. The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: A 2 × 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006;101:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO. Sister to Sister: A community partnered tobacco cessation intervention in low-income housing developments. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2004;65 (2004:UMI No. 3157115) [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Bentley G, Crawford S, Pretlow L, Tingen M. Using community based participatory research to develop a culturally sensitive smoking cessation intervention with public housing neighborhoods. Ethnicity and Disease. 2007a;17:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Cox MJ, Newman SD, Meadows O. The design and initial evaluation of a toolkit to assess partnership readiness for CBPR. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2011;52:183–188. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Heath J. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(4):358–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Waller J, Humbles P. Sister to Sister: A pilot study to assist African American women in subsidized housing to quit smoking. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;6(5):2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Waller J, Tingen M. The effect of a multi-component smoking cessation intervention in African American women residing in public housing neighborhoods. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007b;30(1):45–60. doi: 10.1002/nur.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Newman SD, Meadows O, Cox MJ, Bunting S. Partnership readiness for community-based participatory research. Health Education Research. 2010 doi: 10.1093/her/cyq050. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin D. A model for describing low-income African American women’s participation in breast and cervical cancer early detection screening. Advances in Nursing Science. 1996;19(2):27–42. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG, Steiker LK. A critical analyses of approaches to the development of preventive interventions for subcultural groups. American Journal of Community Psychology, Published online, January. 2011;4:2011. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Pathways to Freedom: Winning the Fight Against Tobacco. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry S, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/path/tobacco.htm#Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E, Auslander W, Munro J. Neighbors for a smoke free north side: evaluation of a community organization approach to promoting smoking cessation in African Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1658–1663. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer K, Barbara K, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 4. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grady G, Ahluwalia J, Pederson L. Smoking initiation and cessation in African Americans attending an inner-city walk-in clinic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:130–137. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E. Review of community-based research: Addressing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman R. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzmann JP, McKnight JL. Building communities from the inside out. Chicago, IL: ACTA Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey L, Manfredi C, Balch G. Social support in smoking cessation among Black women in Chicago public housing. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:99–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Turner N, Burns J, Lee T. Tobacco use and low-income African Americans: policy implications. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(2):332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Lacey L, Warnecke R, Buis M. Smoking-related behavior, beliefs, and social environment of young Black women in subsidized public housing in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:267–272. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Stetcher A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 2):3–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S, Andrews JO, Magwood G, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, Williamson D. Community advisory boards: Synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2011;8:3. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/may/10_0045.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences research. Community based participatory research. 2011 Accessed at: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/scientific_areas/methodology/community_based_participatory_research/index.aspx.

- Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: Conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Education Research. 1998;13:87–108. doi: 10.1093/her/13.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10:282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility vs cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in medical education. Journal of Health Care of Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ. From “water boiling in a Peruvian town” to a “letting them die”: Culture, community intervention, and the metabolic balance between patience and zeal. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47(1–2):58–68. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Beehler S, Deutsch D, Green LW, Hawe P, McLeroy K, et al. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1410–1419. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M. Does one size fit all African American smokers? The moderating role of acculturation in culturally specific interventions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):592–596. doi: 10.1037/a0012968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas MA, Jones N, Eng E, Vines AI, Aronson R, Griffith DM, et al. The art and science of integrating undoing racism with CBPR: challenges of pursuing NIH funding to investigate cancer care and racial equity. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1004–1012. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]