Abstract

Allelic differences between the two homologous chromosomes can affect the propensity of inheritance in humans; however, the extent of such differences in the human genome has yet to be fully explored. Here, for the first time, we delineate allelic chromatin modifications and transcriptomes amongst a broad set of human tissues, enabled by a chromosome-spanning haplotype reconstruction strategy1. The resulting masses of haplotype-resolved epigenomic maps reveal extensive allelic biases in both chromatin state and transcription, which show considerable variation across tissues and between individuals, and allow us to investigate cis-regulatory relationships between genes and their control sequences. Analyses of histone modification maps also uncover intriguing characteristics of cis-regulatory elements and tissue-restricted activities of repetitive elements. The rich datasets described here will enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of how cis-regulatory elements control gene expression programs.

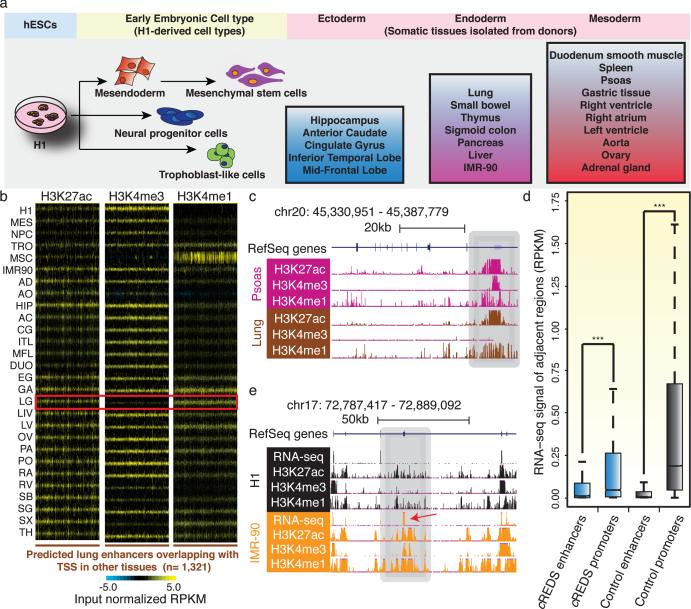

We performed ChIP-seq experiments to generate extensive datasets profiling 6 histone modifications across 16 human tissue-types from four individual donors (181 datasets). Combining with previously published datasets2,3, we conducted in-depth analyses across 28 cell/tissue-types, covering a wide spectrum of developmental states, including embryonic stem cells, early embryonic lineages and somatic primary tissue-types representing all three germ layers (Fig. 1a). The modifications demarcate active promoters (histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac)), active enhancers (H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1) and H3K27ac), transcribed gene bodies (H3 lysine 36 trimethylation (H3K36me3)) and silenced regions (H3K27 or H3K9 trimethylation (H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, respectively))4,5. We systematically identified cis-regulatory elements by employing a random-forest based algorithm (RFECS)2,6, predicting a total of 292,495 enhancers (consisting of 175,912 strong enhancers with high H3K27ac enrichment) across representative samples of all 28 tissues-types (Supplementary table 1). We additionally identified 24,462 highly active promoters with strong H3K4me3 enrichment (see Supplementary Information) (Supplementary table 2). Subsequently, we defined tissue-restricted promoters (n=10,396) and enhancers (n=115,222) (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Consistent with previous studies7-9, enhancers appear more tissue-restricted than promoters and cluster along developmental lineages (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Moreover, tissue-restricted enhancers were enriched for putative binding motifs of particular transcription factors (TFs) known to be important in maintaining the cell/tissue-type's identity and function10-15 (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Epigenome profiles of tissues reveal cREDS with dynamic histone modification signatures.

a) Schematic of the cell/tissue-types profiled and their progression along developmental lineages. Samples include embryonic stem cells (H1), early embryonic lineages (mesendoderm cells(MES), neural progenitor cells (NPC), trophoblast-like cells (TRO) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC)) and somatic primary tissues, representative of all three germ layers (Ectoderm: hippocampus (HIP), anterior caudate (AC), cingulate gyrus (CG), inferior temporal lobe (ITL) and mid-frontal lobe (MFL); Endoderm: lung (LG), small bowel (SB), thymus (TH), sigmoid colon (SG), pancreas (PA), liver (LIV) and IMR-90 fibroblasts; Mesoderm: duodenum smooth muscle (DUO), spleen (SX), psoas (PO), gastric tissue (GA), right heart ventricle (RV), right heart atrium (RA), left heart ventricle (LV), aorta (AO), ovary (OV) and adrenal gland (AD)). b) Heatmaps show H3K27ac, H3K4me3 and H3K4me1 enrichment (RPKM) at predicted lung enhancers (n=1,321), which are defined as promoters in other tissues, across all 28 samples. Red box highlights the signatures in lung. c) A UCSC genome browser snapshot of a region on chromosome 20, showing the chromatin states of a cREDS element (gray shading) predicted as a promoter in psoas and an enhancer in lung. d) A boxplot of RNA-seq signals (RPKM) overlapping ±1kb of cREDS enhancers, cREDS promoters, non-cREDS control enhancers and non-cREDS control promoters. (*** indicates p-value<10e-142, Wilcoxon test) e) RNA-seq and chromatin states of a cREDS element (gray shading) is shown for a region on chromosome 17 in H1 and IMR-90. Arrow indicates an alternate exon incorporated in IMR-90.

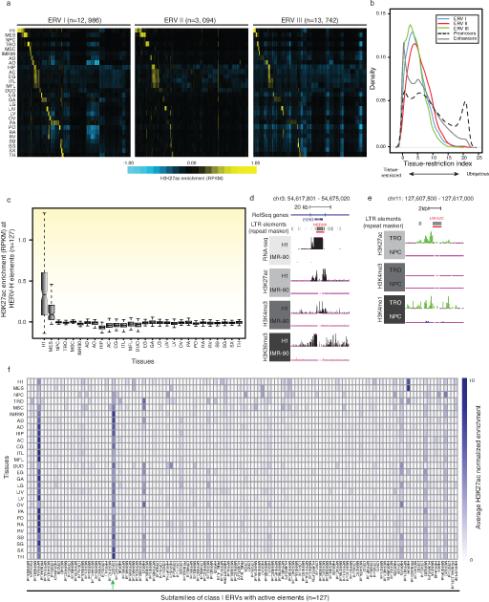

Recent studies showed particular repetitive elements, such as endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), could participate in transcriptional regulation during mammalian development16-18. Given the representation of samples available, we systematically examined histone modifications at different classes of ERVs. While the majority is inactive, subsets, especially class I ERVs (ERV-I), are marked by H3K27ac in a tissue-restricted manner (Extended Data Fig. 3a and b). For instance, HERV-H element activities are restricted to hESCs (Extended Data Fig. 3c and d). Furthermore, some ERVs carried marks of active promoters or enhancers (Extended Data Fig. 3d and e). We also observed LTR12C subfamily had substantial H3K27ac enrichment across different tissues (Extended Data Fig. 3e and f). Interestingly, the individual members appeared tissue restricted, suggesting that although the subfamily can be classified as non-tissue restrictively active, individual LTR12C elements were active only in distinct tissue/cell-types (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Taken together, the data illustrates that human ERVs display precisely controlled patterns of activity in distinct tissues.

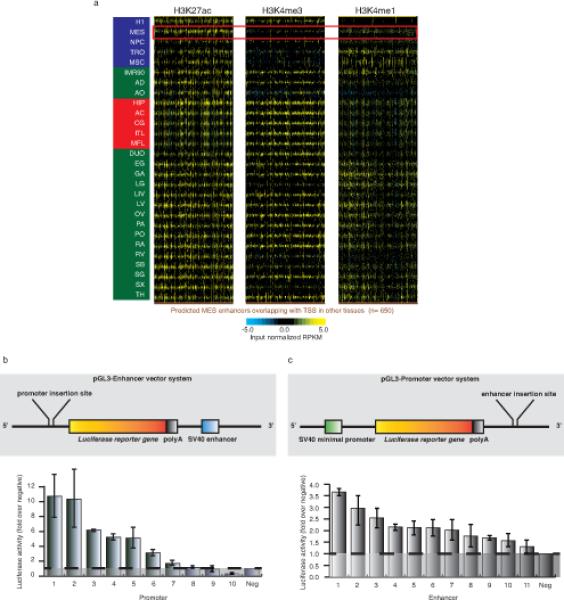

Intriguingly, 15.2% (n=3,717) of strong promoters were also predicted as enhancers in other tissues, analogous to observations in mice, where intragenic enhancers act as promoters to produce cell-type specific transcripts19. These sites possessed histone modification signatures of active enhancers in some tissue/cell-types but were enriched with active promoter marks in others. We termed these sequences cis-Regulatory Elements with Dynamic Signatures (cREDS). For example, cREDS enhancers showed enrichment of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 and a striking depletion of H3K4me3 in lung (Fig. 1b and c, Supplementary table 3). However, the signature shifted to that of active promoters in other tissues (Fig. 1b and c). cREDS are also found in other cell/tissue-types (Extended Data Fig. 4a). To determine whether cREDS are dual functional, we selected a subset of promoter-marked elements and validated their function with a luciferase reporter assay in hESCs. The majority (7 of 10) indeed showed promoter activity (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Similarly, 10 of 11 selected cREDS with enhancer signatures in hESCs also functioned as enhancers (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Additionally, subsets of enhancers previously validated in transgenic mice also possessed dynamic signatures (Extended Data Fig. 5)20. Furthermore, we selected two cREDS, predicted as enhancers in the left heart ventricle, with significant CAGE signal21, typical of active promoters (Extended Data Fig. 6a-b) and found that they possess heart-restricted enhancer activities in an in vivo zebrafish reporter assay (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Consistent with reporter activities, transcriptional properties (RNA-seq values ±1kb of the elements) of cREDS enhancers and promoters are similar to non-cREDS enhancers and promoters, respectively (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, when comparing isoform dynamics across H1 and IMR-90 RNA-seq datasets22, with cREDS identified between these two cell-types, we discovered a subset of cREDS promoters were accompanied by creation of new transcripts and/or alternative exon usage (n=99)(Fig. 1e), revealing a possible function, whereby cREDS influence cell/tissue-specific transcript variants. Taken together, these data show that cREDS can potentially function as both promoters and enhancers in distinct cell-types and fine-tune transcriptomes.

Reasoning that global analysis of allelic histone modification and gene expression patterns would elucidate mechanisms of long-range gene regulation by distal cis-regulatory elements, we re-analyzed RNA-seq and ChIP-seq datasets by considering haplotype information. For this purpose, we applied Haploseq1, which integrated genome sequencing with high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) datasets to derive chromosome-spanning haplotypes (see Supplementary Information). For four different tissue donors, we generated haplotypes spanning entire chromosomes with 99.5% completeness on average (the coverage of haplotype resolved genomic regions) and average resolution (the coverage of phased heterozygous SNPs) ranging from 78% to 89% (Fig. 2a and Supplementary table 4 and 5). The accuracy of haplotype predictions was validated by the concordance with SNPs residing in the same paired-end sequencing reads. The concordance rates were 99.7% and 98.4% for H3K27ac ChIP-seq reads (described below) and RNA-seq reads, respectively, indicating high accuracy. We then re-analyzed 36 mRNA-seq datasets from 18 tissues (including 16 tissues noted above with the addition of bladder and adipose tissue) and 187 ChIP-seq datasets for 6 histone modifications (Supplementary Table 6), from up to 4 individual donors, in a haplotype-resolved context.

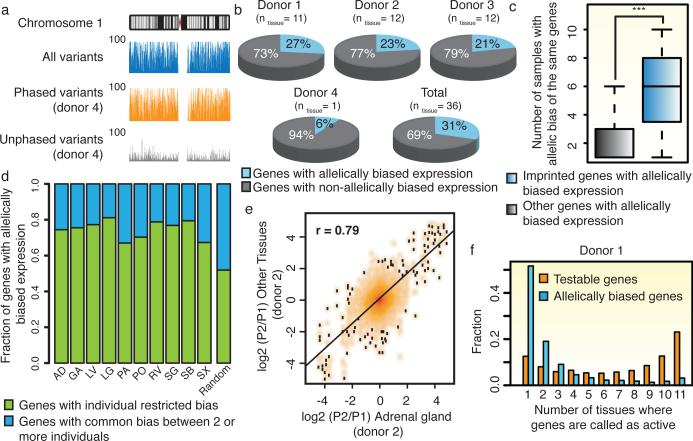

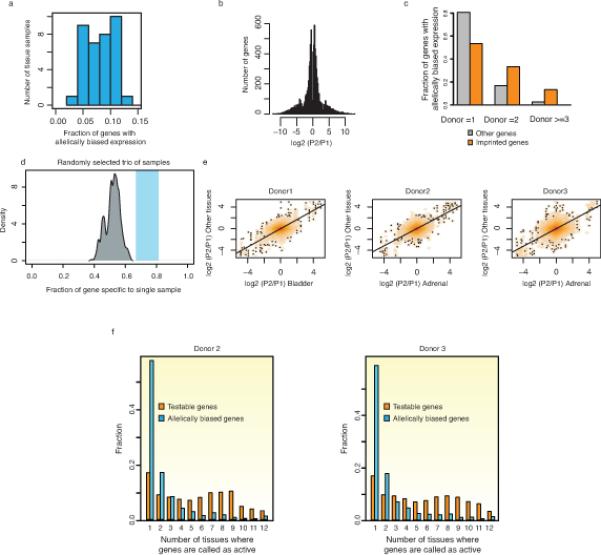

Figure 2. Widespread, individual-specific allelic bias in gene expression.

a) Genome browser snapshots illustrate completeness and resolution of haplotypes resolved in donor 4. Y-axis indicates the number of variants within 100kb windows. The density of all (blue), phased (orange) and unphased (grey) variants across chromosome 1 are shown. b) Proportion of genes with allelically biased expression among informative genes and the number of tissue samples derived from each donor (ntissue) are described. c) Boxplot illustrates occurrence of imprinted and other allelically biased genes across samples. (*** - p-value<9.9e-5, KS-test) d) Including only tissues with 2 or 3 equivalent samples derived from distinct donors (ntissue=10), genes with allelic imbalances were defined as common between individuals (consistent bias among same tissue-type from multiple donors) or as individual-restricted. Random control represents average from randomly selected samples (10,000 iterations). e) Fold change of gene expressions between alleles in AD from donor 2 (x-axis) is compared to all other tissues from donor 2 (y-axis). f) A histogram illustrates the proportions of allelically expressed genes in donor 1 defined in various numbers of tissues. The fraction of all testable genes or allelically expressed genes (y-axis) is calculated for the number of tissues where they are identified as active (x-axis)(p value<2.2e-16, KS-test).

Although widespread allelic imbalances in gene expression had been previously noted7,23-25, it remains unclear whether this phenomenon is consistent across distinct tissues and individuals and the underlying mechanism. To address the prior, we defined genes with allelically biased expression mapping the RNA-seq reads in each tissue sample to the two haploid genomes of the donor. We observed extensive allelically biased gene expression, ranging from 4% to 13% of all informative genes (>10 allelic read counts) in each tissue sample (FDR=5%, Extended Data Fig. 7a-b). Comparatively, the proportion of allelically biased genes in individual tissue donors ranged from 6% to 23% of all informative genes, giving a combined total of 2,570 allelically biased genes (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 7). As a control, known imprinted genes (n=17) showed common allelic biases across multiple samples (Fig. 2c) and donors (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Our datasets, representing the only collection of haplotype-resolved transcriptomes across an array of tissues from multiple individuals, allowed us to characterize allelic transcription across tissues and donors. While most genes with allelically biased expression demonstrate bias in multiple samples, approximately 75% exhibit statistically significant donor-specific bias (Fig. 2d, and Extended Data Fig. 7d). This suggests a connection between sequence differences of individuals and allelically biased gene expression. In support of this model, genes frequently demonstrate consistent direction of allelic bias across multiple tissues of a given donor (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 7e). Interestingly, allelically biased genes were not restricted to the same tissue-type across distinct donors. Rather, they were mostly specific to individual samples derived from each donor (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 7f), possibly resulting from differential levels of tissue-restricted TFs amongst different tissue samples.

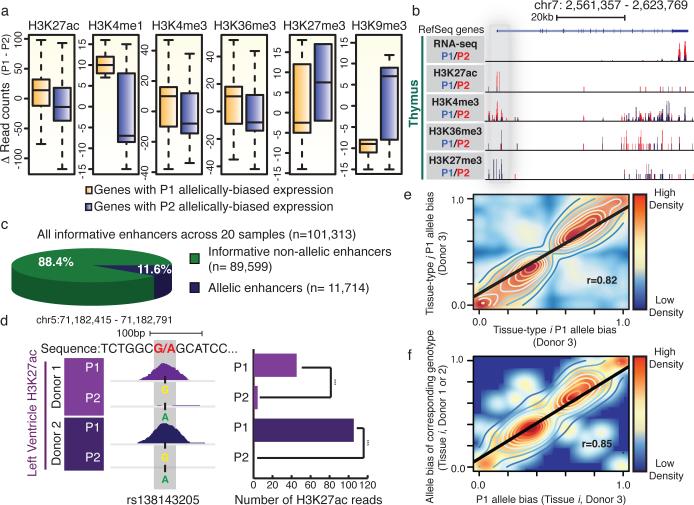

As natural genetic variations can affect enhancer selection and function in mammalian cells26, we hypothesized that polymorphisms at cis-regulatory sequences underlie the widespread allelic transcriptional biases. We thus exploited the unique resource of 187 haplotype-resolved ChIP-seq datasets to analyze the state of cis-regulatory elements. We identified allelically biased marks at promoter regions (H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) and transcribed gene bodies (H3K36me3) (see Supplementary Information). In support of our hypothesis, the allelic biases of gene expression strongly agreed with chromatin states of sequences at or near the genes (Fig. 3a,b, and Extended Data Fig. 8a).

Figure 3. Characterization of allele bias in chromatin states at cis-regulatory elements.

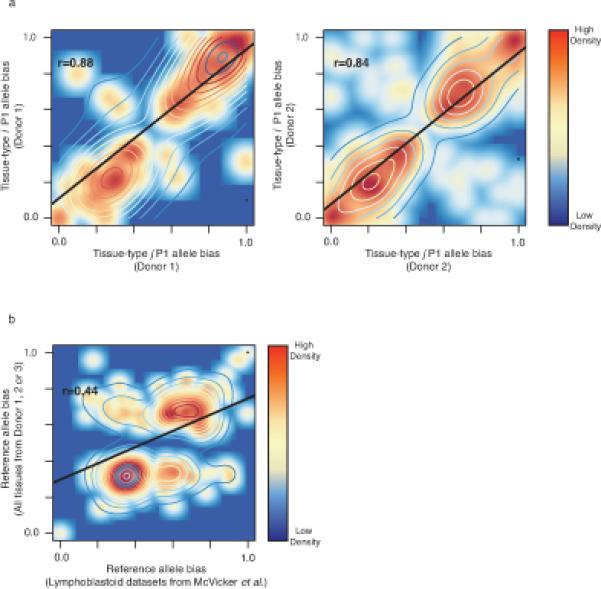

a) Boxplots present haplotype-resolved ChIP-seq reads at promoter or gene bodies (H3K27ac: n=744, p-value=10e-14, H3K4me1: n=32 p-value=0.035, H3K4me3: n=177, p-value=0.0047, H3K27me3: n=12, p-value=0.43, H3K9me3: n=27, p-value=0.13 and H3K36me3: n=291, p-value=4.3e-6, KS-test). b) Allelically biased gene expression of IQCE is concordant with chromatin marks at the promoter (grey) and gene body. c) Proportion of allelic (n=11,714) and non-allelic (n=89, 599) among all informative enhancers (n=101,313) across 20 tissues. d) A snapshot showing a SNP (rs138143205) with H3K27ac bias towards the G allele in both LV donors (Left). Bar chart illustrates the number of H3K27ac reads corresponding to the P1 versus P2 alleles in both donors (Right) (*** - p-value<10e-19, binomial test). e) Scatter plots show strong correlation of the P1 allele bias of enhancer activities among two different tissue-types from donor 3 (n=4,427) and f) among the P1 allele bias in donor 3 (x-axis) and the allele bias of corresponding genotypes in donor 1 or 2 (y-axis) at allelic enhancer in the same tissue-type (n=447).

Furthermore, if allelic imbalances of enhancer activities indeed contributed to allelically biased gene expression, we expected that chromatin states at enhancers would be concordant with the expression of their targets. Therefore, we generated additional H3K27ac ChIP-seq datasets with deeper coverage and longer sequencing reads (for better delineation of alleles) for 14 of the previously analyzed tissue samples and an additional 6 samples from independent donors (Supplementary Table 7). Of the informative enhancers (with >10 polymorphism-bearing sequence reads), 11.6% (n=11,714, FDR=1%) showed significant allelically biased H3K27ac enrichment in any tissue types (Fig. 3c, and Supplementary table 8). H3K27ac biases were validated by allele-specific ChIP-qPCR (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Interestingly, identical genotypes often yielded the same direction of biases in allelic enhancer activities (Fig. 3d). We further tested whether sequence variations are systematically associated with allelic H3K27ac, which reflects enhancer activities27. Indeed, H3K27ac biases were strongly correlated with specific genotypes, whereby given identical genotypes, this histone modification was biased to the same alleles, both across tissue-types and individuals (Fig. 3d-f and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Furthering this finding, we analyzed previously generated datasets from lymphoblastoid cell-lines28 and found similar significant correlation of genotype and molecular phenotype of H3K27ac enrichment (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Taken together, these data reveal that extensive allelic imbalance events are associated with sequence variants in cis-regulatory elements.

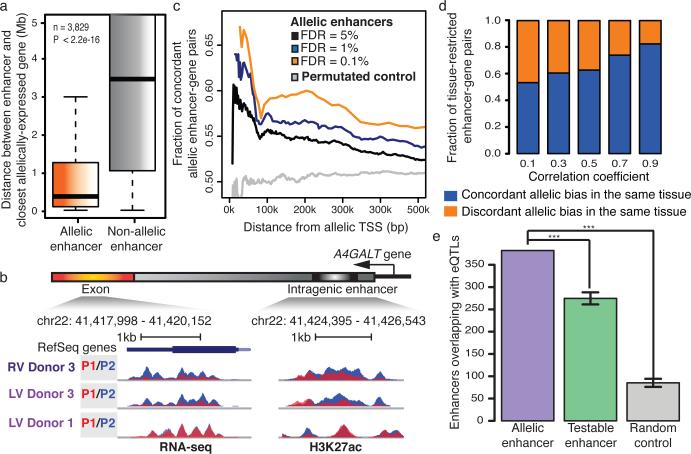

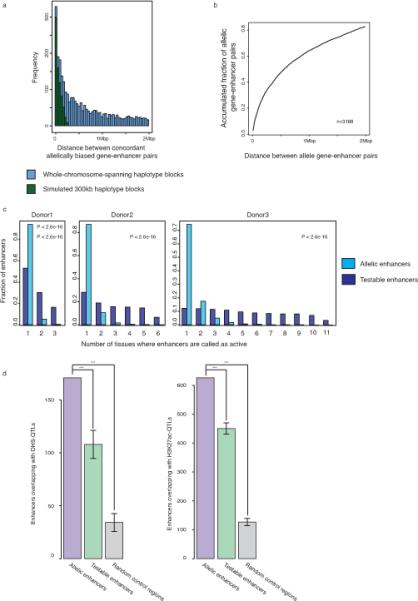

Intriguingly, we discovered allelic enhancers resided in significantly closer proximity to genes with allelically biased expression, as compared to non-allelic enhancers (Fig. 4a and 4b). We also observed examples where distinct tissues from the same donor showed similar allelic biases of gene expression and H3K27ac at enhancers (left ventricle and right ventricle from donor3); however, the same tissue-type derived from a different donor (left ventricle from donor1) yielded no consistent patterns (Fig. 4b), supporting the hypothesis that allelically biased gene expression is driven by individual-specific genetic variation in enhancers. Indeed, within close proximity, the concordance between allelic enhancers and gene expression is significantly higher than permutated control enhancer/gene sets (Fig. 4c). Remarkably, 56% of allelic enhancer-gene pairs are greater than 300kb apart (Extended Data Fig. 10a and b), the delineation of which was enabled by whole chromosome-spanning haplotypes.

Figure 4. Allelic histone acetylation at enhancers is associated with allelically biased gene expression.

a) Average distance of allelic (5% FDR) and non-allelic enhancer to the closest allelically expressed gene is significantly different (n=3,829 *** - p-value<2.2e-16, KS-test). b) Genome browser snapshots show an allelic enhancer within the intron of the allelically expressed A4GALT gene (P1- red, P2 – blue) on chromosome 22 across 3 samples. c) Density plot presents the fraction of concordant allelic bias between allelically expressed genes and allelic enhancers in terms of distance. The allelic enhancer-gene pairs were defined with FDR cutoff values of 5% (n=14,082)(black), 1% (n=6,057)(blue) and 0.1% (n=2,362)(yellow). Permutated control of a set of enhancer-gene pairs was included (n=14,082)(grey). Distance between allelically biased enhancer-gene pairs and fraction of concordant allelic bias are denoted by x- and y-axes, respectively (p-value<2.2e-16, KS-test). d) Fractions of tissue-restricted enhancer-gene pairs (y-axis) that show concordant (blue) or discordant (orange) allelic biases in the same tissue, are presented across a range of Pearson correlation coefficients (x-axis) (p-value < 2.2e-16, KS-test, random permutated control concordant pairs = 50%). (e) Overlap between eQTLs30 and allelic enhancers, testable enhancers or random control regions are shown. Error bars represent standard deviations. Testable enhancers and random control regions were generated 10,000 times with the same numbers as allelic enhancers (*** - p-value<10e-5).

Similar to genes, many allelically biased enhancers are tissue-restricted (Extended Data Fig. 10c). We reasoned that gene expression biases could result from tissue-restricted enhancer activities, supported by significant correlation between allelic enhancers and allelically expressed genes (Fig. 4d). Allelic enhancers also significantly overlapped with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) (Fig 4e), DNaseI hypersensitivity QTLs and H3K27ac QTLs (Extended Data Fig. 10d), defined independently28-30, corroborating the functional roles of identified allelic enhancers on gene regulation. Taken together, these observations support a model whereby allelic biases of cis-regulatory element activities could be responsible for allelic gene expression.

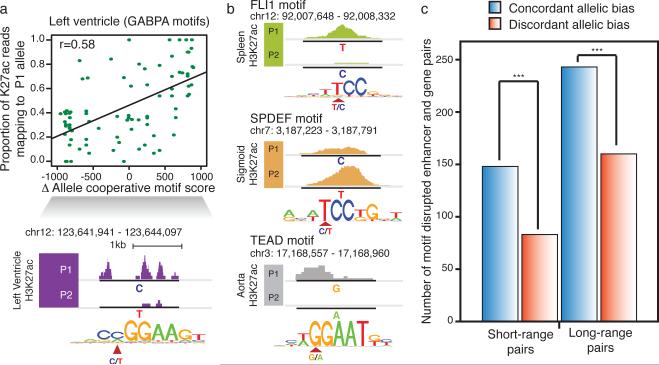

Finally, to further elucidate the mechanism by which allelically biased enhancer activities arise, we examined SNPs that potentially disrupt or weaken TF binding motifs. We calculated changes in motif score between alleles (motif disruption score) at allelic enhancers and discovered 133 TF motifs showing significant concordance between allelic reduction of enhancer activities and TF motif disruption (Fig. 5a and b) (FDR=10%, Supplementary Table 9)(see Supplementary Information). Moreover, genes with allelically biased expression were concordant with enhancer motif disruptions within close proximity (<20kb) or displaying strong Hi-C interactions at longer distances (>20kb)(see Supplementary Information)(Fig. 5c). Our results therefore suggest that genetic variations are likely responsible for allelic enhancer activities and consequently allelically biased gene expression.

Figure 5. Motif disruption by genetic variants is concordant with allelic H3K27ac biases at enhancers.

a) Differential GABPA binding motif scores between two alleles (P1-P2 motif scores) in LV is correlated with the proportion of H3K27ac reads corresponding to the P1 allele (top). Values range from negative to positive, indicating P1 and P2 motif disruption, respectively. An example on chromosome 12 illustrates P1, with a motif preserving C allele, has higher H3K27ac enrichment and the P2, with the motif disrupting T allele, has little H3K27ac enrichment (bottom). b) Three examples (FLI1 in SX, SPDEF in SG, and TEAD in AO) of motif-disrupted enhancers demonstrate allelic biased activities. The variant location and genotypes of P1 and P2 alleles are marked in motif sequence. c) All possible motif disrupted enhancers-gene pairs within the indicated distance window are defined with concordant allelic bias (blue, gene-enhancer pairs with biases towards the same allele) or discordant allelic bias (red, gene-enhancer pairs with biases towards different alleles). Only TH, LV and AO were considered due to the availability of Hi-C data. Short-range pairs are defined if any allelically expressed genes are located <20kb away. (*** - p-value<2.5e-5, binomial test).

In summary, by generating chromosome-spanning haplotypes, we carried out a comprehensive survey of allelic chromatin state and gene expression. We found evidence for extensive allelically biased gene expression, which is connected to change in chromatin states at cis-regulatory elements, likely resulting from TF binding disruption by sequence variations. These observations echo findings in mice where allelic biases of cis-regulatory element activities could be responsible for allelic gene expression26 and demonstrate that such phenomenon is likely widespread in the human genome, too. These observations shed light on the importance of considering genetic variants in understanding individual-specific gene regulation. Analyses of haplotype-resolved transcriptomes and epigenomes in additional individuals and tissues should further illuminate the role of sequence variations in defining individual-specific transcriptional programs and phenotypes.

Extended Data

Extended data Figure 1. Active enhancers cluster along developmental lineages.

a) Pie charts showing fractions of tissue-restricted and non-tissue-restricted strong enhancers and promoters. b) Hierarchical clustering with optimal leaf ordering based on all H3K27ac marked highly active enhancers. Four major clusters are represented: early embryonic cell-types (blue), a large set of meso/endoderm-derived tissues (dark green), a set consisting of ectoderm-derived brain tissues (red) and a small cluster of mesoderm cell lines (purple), which bridged the early embryonic lineages with the somatic tissues. It is worth noting that although TRO did not fall within any clusters, it shared the highest degree of similarity with the early embryonic cell lines. On a subsequent level, two clusters are seen separating endoderm-derived tissues (gray line) and mesoderm-derived tissues (green line). Heart tissues are denoted by yellow asterisk. c) Clustering of tissues by promoters histone acetylation status shows grouping of tissues that are of similar types but are less evident in germ-layer divisions than clustering of enhancers.

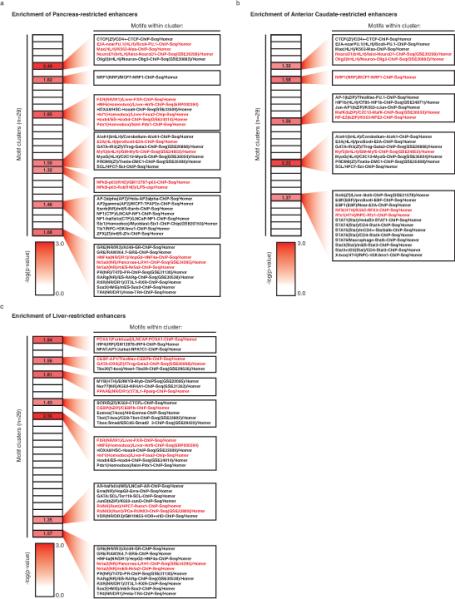

Extended data Figure 2. Tissue-restricted enhancers are enriched for TF motifs important for cell identity and/or function.

Significantly enriched motifs (p-value<10e-10) across all 28 tissues are divided into 29 clusters (method described in Supplementary Information). An overall p-value is generated for the enrichment of each tissue for each cluster. The figure illustrates –log(p-value) of a) pancreas b) anterior caudate and c)liver-restricted enhancer motif enrichment for the various clusters. For ease of visualization, any cluster with p-values greater than 0.05 is denoted 0. Red highlighted text refers to a subset of motif for TFs with literature support (See Supplementary Information) to have function in a) the pancreas, b) the brain and c) the liver.

Extended data Figure 3. Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are enriched for active cis-regulatory element marks in a tissue-restricted fashion.

a) A clustered heatmap showing the H3K27ac enrichment (RPKM) of all mappable elements of the 3 classes of ERVs. b) Distribution of the Shannon-entropy of H3K27ac across enhancers, promoters and 3 classes of ERVs is shown as a density curve, demonstrating that H3K27ac enrichment of ERVs are more tissue-restricted than promoters and slightly less than enhancers. c) Boxplots illustrating the H3K27ac enrichment of 127 mappable members of the HERV-H subfamily across all tissue/cell-types. The enrichment in H1 hESCs is significantly higher than all other cell/tissues-types (p-value<1.4e-9, Wilcoxon test). d) UCSC genome browser snapshots showing example of an HERV-H element harboring H1-restricted active promoter marks, corresponding RNA-seq signal and H3K36me3 enrichment. It is note worthy that this particular element has been annotated in Refseq as the ES cell Related Gene (ESRG), a human-specific long non-coding RNA gene. e) UCSC genome browser snapshots showing example of a LTR12C element harboring TRO-restricted active enhancer chromatin marks. f) A matrix illustrating the average H3K27ac enrichment for subfamilies of class I ERVs across all cell- and tissue-types. LTR12C subfamily (green arrow) shows enrichment of H3K27ac across many distinct cell-types and tissues.

Extended data Figure 4. cREDS are enriched with dynamic histone mark signatures in different tissues and have putative cis-regulatory functions.

a) Heatmaps showing the enrichment (RPKM) of the H3K27ac, H3K4me3 and H3K4me1 at MES-restricted enhancers (n=650), which are predicted as promoters in other tissues, across all 28 samples. The red box highlights the histone modifications in MES cells. b) A schematic of the pGL3-enhancer vector used in these luciferase-reporter assays (top) and the activity of 10 selected cREDS with promoter signatures and a negative control region cloned 5’ to the reporter gene after transfection into H1 hESCs (bottom). Luciferase activity of each region is normalized to the average activity of the negative controls. c) A schematic of the pGL3-promoter vector used in these luciferase-reporter assays (top) and the activity of 11 selected cREDS with enhancer signatures and a negative control region cloned 3’ to the reporter gene after transfection into H1 hESCs (bottom). Luciferase activity of each region is normalized to averaged activity of negative control regions. Error bars reflect standard deviation between 3 technical replicates

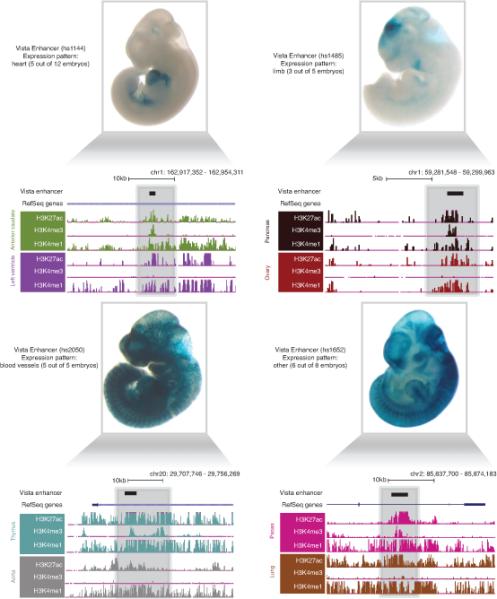

Extended data Figure 5. VISTA validated enhancers also possess dynamic histone modification signatures across tissues.

Example screen shots of VISTA validated enhancers and the patterns of activity in vivo are displayed along with histone modification patterns in representative tissues (adapted from VISTA enhancer browser20).

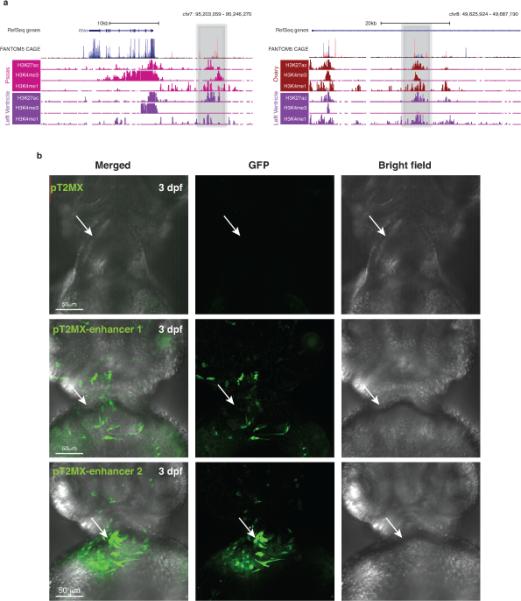

Extended data Figure 6. cREDS show enrichment of CAGE signal and putative enhancer functions in zebrafish reporter assay.

a) UCSC genome browser screen shots show the 2 cREDS elements (Grey shading) harboring enhancer and promoter signatures in distinct tissue types. When compared to CAGE datasets from the FANTOM5 project, these elements show substantial overlap with transcript signals (red and blue signals indicate CAGE signal on the forward and reverse orientation, respectively). b) Selected cREDS (same elements as above) with enhancer marks in left ventricle shows heart-restricted enhancer activity, as indicated by GFP expression, in 3 days post-fertilization (3 dpf) zebrafish larvae. In parallel pT2MX negative control did not show any GFP expression. White arrow indicates location of the 3dpf zebrafish heart. For enhancer 1, 13 out of the 38 surviving embryos showed similar patterns. For enhancer 2, 18 out of the 35 surviving embryos showed similar patterns. None of the 30 surviving embryos, injected with the control vector, showed any appreciable GFP signal in the heart. (Scale bar = 50 μm)

Extended data Figure 7. Identification of widespread allelically expressed genes.

a) Fraction of genes with allelically biased expression in each sample. Y-axis indicates number of samples and x-axis indicates fraction of allelically biased genes among informative genes (more than 10 SNP-containing short reads). b) Distribution of fold change of allelically biased genes between P1 and P2 alleles. c) The occurrence of allelically biased imprinted and other genes is shown. X-axis refers to the number of individual donors where corresponding allelically expressed genes are commonly detected. d) A density plot showing the fraction of sample-restricted genes with allelically biased expression (grey). Three tissue samples were randomly selected and, sample-restricted allelically expressed genes were defined, which includes random variance effect. The random selection was repeated 10,000 times. Shaded blue box indicates the range of fractions of individual-restricted allele biased genes in all analyzed tissues-types (n=10). The fraction of sample-restricted allelically biased genes is lower than individual-restricted allele biased genes in Figure 2e. e) Fold change of allele biased gene expression between two alleles are shown as scatter plot. X-axis is for the fold changes in one randomly selected tissue in each donor and y-axis is for the fold changes in all other remaining tissues in the corresponding donor. Allelic bias in one tissue is highly correlated with allelic bias in other tissues in the same individual. f) A histogram illustrates the proportions of allelically expressed genes in donor 2 (left) and 3 (right) defined in various numbers of tissues. The fraction of all testable genes or allelically expressed genes (y-axis) is calculated for the number of tissues where they are called as active (x-axis). The results indicate that the majority of allelically biased genes, as oppose to testable genes, are restricted to 1 or 2 tissue samples. KS-test was performed between allele biased genes and testable genes (p-value < 2.2e-16).

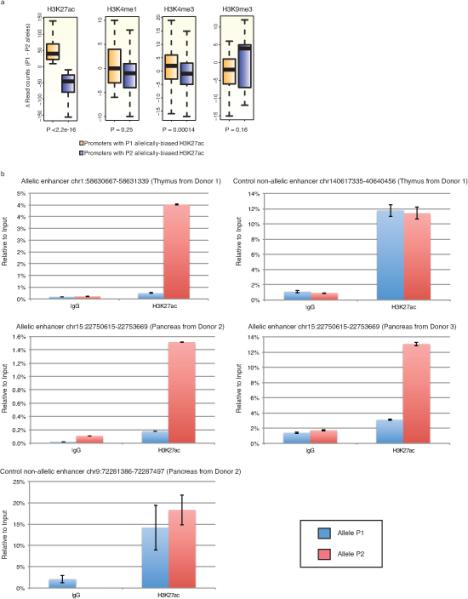

Extended data Figure 8. Allele biased chromatin states.

a) Boxplots illustrating haplotype-resolved ChIP-seq signal enrichment on the two alleles at promoter regions. The P1 or P2 allele biased promoter regions were defined by H3K27ac signals and then H3K4m1, H3K4me3, and H3K9me3 signals were presented for the corresponding promoter regions. All chromatin states are consistent according to the allele biased H3K27ac patterns. KS-test was performed for p value calculation. b) Allelically biased enhancers were tested in thymus from donor 1, pancreas from donor 2 and 3. H3K27ac enrichment was tested by allele-specific ChIP-qPCR. Two control enhancers were included and showed to have no allelic biases in thymus or pancreas from donor 2 (top right and bottom left, respectively).

Extended data Figure 9. Putative enhancers with identical genotypes in different individuals exhibit similar biases in histone acetylation.

a) Scatter plots of P1 allele biased enhancer activities for pairwise comparison of allele biased enhancers in donor 1 (n=85) and donor 2 (n=4,427). X- and y-axis indicate P1 allele bias. b) Scatter plot of reference allele bias of enhancer activities for pairwise comparison of allele biased enhancers in all tissues from all three donors and lymphoblastoid datasets obtained from a previous study28 (n=309).

Extended data Figure 10. Analyses of concordant allelically biased gene-enhancer pairs.

a) Frequency of allelically expressed genes according to the distance between concordantly allele biased enhancer-gene pairs. Blue bars represent data obtained from whole chromosome-spanning haplotype blocks while green bars represent data obtained from simulated 300kb haplotype blocks. 56% of enhancer-gene pairs are more than 300kb apart. b) Accumulation curve showing fraction of allelically biased genes that have at least one concordantly allelic enhancer within a given distance (x-axis). Up to 83% of allelically expressed genes are within 2Mb of a concordantly biased allelic enhancer. c) The frequency of allele biased enhancers in donor 1, 2, and 3. Y-axis indicates fraction of enhancers and x-axis indicates frequency of allelically biased enhancers. KS-test was performed between allele biased enhancers and testable enhancers. d) Bar plots presenting the number of enhancers overlapping with DHS-QTLs and H3K27ac-QTLs for allelic enhancers, testable enhancers, and random control regions (*** - p value <10e-5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NIH Epigenome Roadmap Project (U01 ES017166) and CIRM RN2-00905-1. We thank Ashwinikumar Kulkarni and Jie Wu for help with processing RNA-seq datasets and Yupeng He and Matthew Schultz for discussions regarding allelic analyses of RNA-seq datasets. We also thank members of the Ren lab for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

D.L., W.X., J.E., N.C. and B.R. led the data production. I.J, N.R., M.Q.Z., J.E. and B.R led the data analyses. I.J, N.R, S.S. F.Y., Y.Q., L.E., M.H., and P.R conducted analyses. S.L. and Y.L. processed tissue samples. D.L. A.S. A.Y.L. C.Y. S.K. and H.Y. produced data. D.L., I.J., N.R. and B.R. wrote the manuscript.

Author Information

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets were deposited to GEO under the accession number GSE16256. Hi-C datasets were deposited to GEO under the accession number GSE58752.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of this paper.

References

- 1.Selvaraj S, J RD, Bansal V, Ren B. Whole-genome haplotype reconstruction using proximity-ligation and shotgun sequencing. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31:1111–1118. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2728. doi:10.1038/nbt.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie W, et al. Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1134–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J, et al. Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell. 2013;152:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivera CM, Ren B. Mapping human epigenomes. Cell. 2013;155:39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heintzman ND, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nature genetics. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. doi:10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajagopal N, et al. RFECS: a random-forest based algorithm for enhancer identification from chromatin state. PLoS computational biology. 2013;9:e1002968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002968. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang F, et al. Genomic landscape of human allele-specific DNA methylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:7332–7337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201310109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201310109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stergachis AB, et al. Developmental fate and cellular maturity encoded in human regulatory DNA landscapes. Cell. 2013;154:888–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson R, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. doi:10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flandez M, et al. Nr5a2 heterozygosity sensitises to, and cooperates with, inflammation in KRas(G12V)-driven pancreatic tumourigenesis. Gut. 2014;63:647–655. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304381. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirai H, et al. Involvement of Runx1 in the down-regulation of fetal liver kinase-1 expression during transition of endothelial cells to hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2005;106:1948–1955. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4872. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-12-4872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang DH, et al. Transplantation of human neural stem cells transduced with Olig2 transcription factor improves locomotor recovery and enhances myelination in the white matter of rat spinal cord following contusive injury. BMC neuroscience. 2009;10:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-117. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahan I, Kersigo J, Pan N, Fritzsch B. Neurod1 regulates survival and formation of connections in mouse ear and brain. Cell and tissue research. 2010;341:95–110. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0984-6. doi:10.1007/s00441-010-0984-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CS, et al. Loss of nuclear factor E2-related factor 1 in the brain leads to dysregulation of proteasome gene expression and neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:8408–8413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019209108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019209108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moya M, et al. Foxa1 reduces lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes and is down-regulated in nonalcoholic fatty liver. PloS one. 2012;7:e30014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunarso G, et al. Transposable elements have rewired the core regulatory network of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:631–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.600. doi:10.1038/ng.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie M, et al. DNA hypomethylation within specific transposable element families associates with tissue-specific enhancer landscape. Nat Genet. 2013;45:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ng.2649. doi:10.1038/ng.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X, et al. The retrovirus HERVH is a long noncoding RNA required for human embryonic stem cell identity. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2014;21:423–425. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2799. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalczyk MS, et al. Intragenic enhancers act as alternative promoters. Mol Cell. 2012;45:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.021. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visel A, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Pennacchio LA. VISTA Enhancer Browser--a database of tissue-specific human enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D88–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl822. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium F, et al. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature. 2014;507:462–470. doi: 10.1038/nature13182. doi:10.1038/nature13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trapnell C, et al. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. doi:10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimelbrant A, Hutchinson JN, Thompson BR, Chess A. Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science. 2007;318:1136–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1148910. doi:10.1126/science.1148910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilpinen H, et al. Coordinated effects of sequence variation on DNA binding, chromatin structure, and transcription. Science. 2013;342:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1242463. doi:10.1126/science.1242463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skelly DA, Johansson M, Madeoy J, Wakefield J, Akey JM. A powerful and flexible statistical framework for testing hypotheses of allele-specific gene expression from RNA-seq data. Genome research. 2011;21:1728–1737. doi: 10.1101/gr.119784.110. doi:10.1101/gr.119784.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinz S, et al. Effect of natural genetic variation on enhancer selection and function. Nature. 2013;503:487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature12615. doi:10.1038/nature12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McVicker G, et al. Identification of genetic variants that affect histone modifications in human cells. Science. 2013;342:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1242429. doi:10.1126/science.1242429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasowski M, et al. Extensive variation in chromatin states across humans. Science. 2013;342:750–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1242510. doi:10.1126/science.1242510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lappalainen T, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. doi:10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.