Abstract

IMPORTANCE

To our knowledge, few published studies have examined the influence of competitive food and beverage (CF&B) policies on student weight outcomes; none have investigated disparities in the influence of CF&B policies on children’s body weight by school neighborhood socioeconomic resources.

OBJECTIVE

To investigate whether the association between CF&B policies and population-level trends in childhood overweight/obesity differed by school neighborhood income and education levels.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

This cross-sectional study, from July 2013 to October 2014, compared overweight/obesity prevalence trends before (2001–2005) and after (2006–2010) implementation of CF&B policies in public elementary schools in California. The study included 2 700 880 fifth-grade students in 5362 public schools from 2001 to 2010.

EXPOSURES

California CF&B policies (effective July 1, 2004, and July 1, 2007) and school neighborhood income and education levels.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Overweight/obesity defined as a body mass index at or greater than the 85th percentile for age and sex.

RESULTS

Overall rates of overweight/obesity ranged from 43.5% in 2001 to 45.8% in 2010. Compared with the period before the introduction of CF&B policies, overweight/obesity trends changed in a favorable direction after the policies took effect (2005–2010); these changes occurred for all children across all school neighborhood socioeconomic levels. In the postpolicy period, these trends differed by school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage. From 2005–2010, trends in overweight/obesity prevalence leveled off among students at schools in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods but declined in socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods. Students in the lowest-income neighborhoods experienced zero or near zero change in the odds of overweight/obesity over time: the annual percentage change in overweight/obesity odds was 0.1% for females (95% CI, −0.7 to 0.9) and −0.3% for males (95% CI, −1.1 to 0.5). In contrast, in the highest-income neighborhoods, the annual percentage decline in the odds of overweight was 1.2% for females (95% CI, 0.4 to 1.9) and 1.0% for males (95% CI, 0.3 to 1.8). Findings were similar for school neighborhood education.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Our study found population-level improvements in the prevalence of childhood overweight/obesity that coincided with the period following implementation of statewide CF&B policies (2005–2010). However, these improvements were greatest at schools in the most advantaged neighborhoods. This suggests that CF&B policies may help prevent child obesity; however, the degree of their effectiveness is likely to depend on socioeconomic and other contextual factors in school neighborhoods. To reduce disparities and prevent obesity, school policies and environmental interventions must address relevant contextual factors in school neighborhoods.

The sale of foods and beverages in schools outside of school meal programs has received considerable attention in the United States over the past decade.1,2 Items such as soda, candy, and chips are called competitive foods because they are available alongside and compete with school meal programs.3 Concerns about competitive food and beverages (CF&Bs) emerged as research documented their nearly universal availability in US schools3–5; high levels of sugar, fat, and calories6; and linkage with unhealthy student diets4,5 and weight status in some,7,8 although not all, studies.9,10

To prevent childhood obesity, 75% of states and many school districts have adopted policies to regulate CF&B items in schools.11,12 The policies vary in scope but have generally sought to reduce fat and sugar in CF&B items, as well as limit their availability to students.12,13 Reinforcing these efforts, the US Department of Agriculture issued an interim final rule on the sale of high-density foods and beverages in schools, effective 2014–2015.14

In 2001 and 2003, California enacted among the most comprehensive CF&B policies in the nation, requiring substantial changes to public school food environments, although standards varied by school level. Effective July 1, 2004, California Senate bill 677, aimed at students in kindergarten through eighth grade, prohibited the sale of sugary beverages; required at least 50% fruit juice with no added sweeteners; eliminated added sweeteners from water and sports beverages; and limited the fat content in milk to 2%. Effective July 1, 2007, Senate bill 12 set statewide nutrition and portion size standards for competitive foods for students in kindergarten through eighth grade. The state nutrition rules for snacks in elementary schools limit the percentage of total calories from fat to 35%, the percentage of calories from saturated fats to 10%, and sugar content in snacks to 35% or less by weight. Senate bill 12 also expanded beverage standards into high schools.

To our knowledge, few published studies have examined the impact of CF&B policies on student weight outcomes15,16; none have investigated whether the influence of CF&B policies on children’s body weight differs based on the socioeconomic resources of school neighborhoods. Students in socioeconomically disadvantaged schools are more likely to be overweight or obese than students in more affluent schools.17 Some national studies have observed modest18 or no associations between the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals and either the availability of CF&Bs, including salty, low-fat, or sweet products, at any venue19; access to competitive food venues20; or availability of sugary beverages when state laws prohibited their sales.18 National studies have also found that parental education was positively associated with the availability of healthier foods21 and that lower-income schools had fewer available healthier products.20 A study of Utah schools found that socioeconomically advantaged schools were significantly less likely to allow lunch-time purchase of unhealthful snacks,22 suggesting that students in affluent schools may be more exposed to healthier food options. Given the pressing need for effective interventions to prevent childhood obesity at the population level, it is important to understand the relationship between CF&B policies and child obesity across schools located in socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods.

Using a natural experiment in California for this study conducted from July 2013 to October 2014, we built on a prior study23 to examine (1) whether changes in childhood overweight/obesity trends before and after implementation of statewide CF&B policies differed depending on the level of socioeconomic resources in school neighborhoods and (2) whether, in the postpolicy period, child overweight/obesity trends differed by school neighborhood socioeconomic resources.

Methods

Study Population

Because California statewide policies differ for elementary, middle, and high schools and because early-life nutritional habits are linked to child development and long-term health,24 this study focused on fifth-grade students who attended California public elementary schools each year from 2001 to 2010. The state CF&B policies applicable to these students have been in effect since 2004. The combined analytic data set included 2 700 880 students in 5362 schools over the 10-year period.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; informed consent does not apply as students are required to take the test regardless of enrollment in a physical education class.25

Sources of Data and Study Variables

Since 1999, California has collected physical fitness data via a physical fitness test (Fitnessgram), including measures of the height and weight of all public school students in fifth, seventh, and ninth grades annually between February and May.25 The Fitnessgram database is available from the California Department of Education. To account for school- and district-level characteristics, we used unique school and geocoded addresses to merge 2001 through 2010 Fitnessgram data with school and district data from the California Department of Education and the 2000 Census.

Student-Level Variables

All student-level information was derived from Fitnessgram data. The primary outcomes were body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) percentile and weight status. Body mass index values were compared with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 Growth Charts.26 Students were classified as overweight/obese if their age- and sex-specific BMI was at or greater than the 85th percentile.26 Because the intended purpose of the CF&B policies was to prevent child obesity and because overweight children are at greatest risk for becoming obese, we were interested in how policies might affect trends in both overweight and obesity and thus used this combined outcome. Other student-level variables included sex, age in years, race/ethnicity (white, Hispanic, black, and Asian), and fitness level (meeting or exceeding fitness standards vs not, based on the Cooper Institute’s guidelines for the time to run 1 mile).27 Students with missing values for BMI (range, 6.5%–14%) or demographic variables (≤1.4%) were excluded from all analyses; students with missing values for fitness level were included but categorized as missing for that variable.

School-Level Variables

Because school characteristics might influence the implementation of CF&B policies and students’ body weight, we adjusted for several school-level variables. School size was measured as the total number of enrolled students. School racial/ethnic composition was defined based on California Department of Education information about the percentage of students in 4 major racial/ethnic groups: a school was classified as majority for a specific racial/ethnic group if it included at least 50% of students; if no single racial/ethnic group included at least 50% of students or the majority of students was from a racial/ethnic group other than white, black, Hispanic, or Asian, the school was classified as other or no majority. Because no student-level socioeconomic information was available in Fitnessgram, we used the school-level proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals as an indicator of children’s socioeconomic characteristics, which have been associated with childhood overweight status.

School Neighborhood Data

Census data were used to classify each school according to the level of socioeconomic resources in its surrounding neighborhood, constructing tertiles (lowest, medium, and highest) of the distributions of school neighborhood income level (measured as annual median household income of residents in the census tract where the school was located) and educational attainment (measured as the proportion of census tract residents ages 25 years and older with 16 or more years of education).

District-Level Variables

Because implementation of CF&B policies is directed at the district level, we included school-district characteristics: the total numbers of schools and of enrolled students and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive Analyses

We obtained the means and standard deviations or frequencies, as appropriate, of student-, school-, and district-level characteristics for the overall sample and within strata defined by level of school neighborhood income and education.

Models

Assuming that impacts of CF&B policies accrue gradually over time, we compared the annual change in the prevalence of overweight/obesity (ie, the slopes of the trend lines fitted to yearly prevalence) before and after the policies went into effect by levels of school neighborhood income or education.28 We estimated annual changes in overweight/obesity prevalence using multilevel logistic regression models with overweight/obesity as the outcome. We estimated changes in slopes after the policies took effect by including a term for year since 2001 to capture the slope prior to the policies and a linear spline term with a knot placed at 2005. Although the first policy went into effect in 2004, 2005 is used as a marking point for policy effects because it is likely to take time for policies to influence body weight; some schools began to implement changes to CF&B practices in 200529; and the data provide a better fit with a knot in 2005 vs 2004. This is consistent with the assumption that both policies influenced body-weight trend changes.

Cross-product interactions between tertiles of school neighborhood income and education and the year and spline terms were used to obtain trends in each neighborhood income and education level and to test whether slopes in childhood overweight/obesity prevalence during the period following policy implementation differed significantly for students attending schools in the lowest and middle tertiles relative to those in the highest tertile of neighborhood advantage. The model included multivariate normal random effects (random intercepts and slopes for the year and spline terms) with an unstructured covariance matrix at the school-district and schools-within-district levels to (1) account for clustering among students; (2) incorporate heterogeneity28 of trends at both levels; and (3) derive inferences28 at the level of school district. Student-, school-, and district-level covariates served as adjustment factors. Supplemental models were repeated using obesity (age- and sex-specific BMI z scores ≥95th percentile) as the outcome. Separate models were constructed for boys and girls because prior research has documented that the timing of adiposity differs by sex. Analyses were completed using the R statistical package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

During the study, 33% of students were white, 56.7% Hispanic, 4.7% black, and 5.5% Asian (Table 1); however, racial/ethnic composition differed by school neighborhood income and education tertiles. The proportion of white and Asian students was higher at schools in the highest levels of school neighborhood income and education, while the proportion of Hispanic and black students was higher in schools in more socioeconomically disadvantaged school neighborhoods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of California Fifth-Grade Public School Students Overall and by Tertile of School Neighborhood Income and Educational Attainmenta

| Characteristic | Fifth-Grade Students, 2001–2010, %

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 3 175 781) | School Neighborhood Incomeb

|

School Neighborhood Educationc

|

|||||

| Lowest (n = 1 124 332; 35.4%) | Middle (n = 1 016 919; 32.0%) | Highest (n = 1 034 530; 32.6%) | Lowest (n = 1 235 135; 38.9%) | Middle (n = 994 403; 31.3%) | Highest (n = 946 243; 29.8%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| White | 33.1 | 13.8 | 28.8 | 58.4 | 10.2 | 33.9 | 62.3 |

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic | 56.7 | 77.6 | 63.1 | 27.7 | 82.6 | 56.8 | 22.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Black | 4.7 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 2.9 |

|

| |||||||

| Asian | 5.5 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 11.0 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 12.1 |

|

| |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Male | 51.1 | 50.7 | 51.2 | 51.5 | 50.7 | 51.2 | 51.5 |

|

| |||||||

| Female | 48.9 | 49.3 | 48.8 | 48.5 | 49.3 | 48.8 | 48.5 |

|

| |||||||

| Age, y | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 10 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.6 | 53.9 | 53.7 | 53.6 | 53.9 |

|

| |||||||

| 11 | 43.3 | 42.4 | 43.4 | 44.4 | 42.4 | 43.4 | 44.4 |

|

| |||||||

| 12 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Physical fitnessd | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Unfit | 31.7 | 37.3 | 33.8 | 23.6 | 37.5 | 33.7 | 22.1 |

|

| |||||||

| Fit | 36.5 | 35.6 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 36.0 | 36.5 | 37.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Super fit | 17.7 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 22.8 | 14.8 | 15.8 | 23.4 |

|

| |||||||

| Missing | 14.1 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 15.8 | 11.6 | 14.0 | 17.3 |

|

| |||||||

| Overweight/obesee | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 2001 | 43.5 | 49.7 | 45.3 | 35.0 | 50.5 | 44.2 | 33.8 |

|

| |||||||

| 2002 | 44.1 | 50.0 | 46.1 | 35.7 | 50.7 | 45.1 | 34.4 |

|

| |||||||

| 2003 | 45.1 | 51.3 | 46.9 | 36.5 | 52.0 | 45.9 | 35.2 |

|

| |||||||

| 2004 | 45.3 | 51.6 | 47.3 | 36.3 | 52.4 | 46.0 | 35.1 |

|

| |||||||

| 2005 | 46.6 | 52.9 | 48.8 | 37.1 | 53.8 | 47.4 | 35.8 |

|

| |||||||

| 2006 | 46.2 | 52.7 | 48.6 | 36.5 | 53.3 | 47.4 | 35.2 |

|

| |||||||

| 2007 | 45.9 | 52.8 | 48.3 | 36.1 | 53.2 | 47.5 | 34.6 |

|

| |||||||

| 2008 | 46.0 | 52.7 | 48.5 | 36.5 | 53.6 | 47.4 | 34.8 |

|

| |||||||

| 2009 | 45.9 | 52.8 | 48.4 | 36.3 | 53.7 | 47.0 | 34.8 |

|

| |||||||

| 2010 | 45.8 | 52.8 | 48.3 | 36.2 | 53.7 | 47.0 | 34.8 |

Our analysis of data from the California Fitnessgram (2001–2010), California Department of Education.25

Neighborhood income is measured as annual median household income in the census tract where a school was located, and schools are grouped into income tertiles.

Neighborhood education is measured as the proportion of school census tract residents who were ages 25 years and older and had 16 or more years of education, and schools are grouped into education tertiles.

Physical fitness is defined as scoring within the Cooper Institute’s Fitnessgram healthy fitness zone according to performance on the 1-mile run or walk.

Overweight/obesity is defined as age- and sex-specific body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) at or above the 85th percentile of the reference distribution.

Schools in neighborhoods with the lowest median annual household income had the lowest proportion of neighborhood residents who completed a college degree, higher student enrollment, and the highest proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals (Table 2). Among schools in disadvantaged neighborhoods, 74% had majority Latino student bodies. Conversely, schools in socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods had the lowest student enrollment and the lowest proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals; 62% had majority white student populations.

Table 2.

Characteristics of California Public Schools Overall and by School Neighborhood Education and Income Tertilesa

| Characteristic | Mean (SD)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 5362) | School Neighborhood Incomeb

|

School Neighborhood Educationc

|

|||||

| Lowest (n = 1762, 32.86%) | Middle (n = 1768, 32.97%) | Highest (n = 1832, 34.17%) | Lowest (n = 1789, 33.36%) | Middle (n = 1762, 32.86%) | Highest (n = 1811, 33.78%) | ||

| School’s neighborhood-level education (% Bachelor degrees) | 23.3 (17.4) | 10.5 (8.4) | 20.0 (11.5) | 38.8 (16.6) | 7.1 (3) | 18.9 (4.1) | 43.7 (13.1) |

|

| |||||||

| School’s neighborhood-level median household income, $ | 51 492 (23 031) | 29 919 (6067) | 46 919 (4836) | 76 655 (19 836) | 34 382 (10 278) | 47 741 (12 707) | 72 044 (24 165) |

|

| |||||||

| School enrollment, No. | 599 (258) | 637 (309) | 585 (247) | 576 (204) | 670 (286) | 587 (259) | 541 (205) |

|

| |||||||

| Free or reduced-price meal program | 54.1 (29.8) | 76.8 (19.6) | 58.3 (23.3) | 28.1 (22.7) | 78.7 (17.1) | 54.7 (23.5) | 29 (24.1) |

|

| |||||||

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic | 42.7 | 66.6 | 48.3 | 14.3 | 77.2 | 40.0 | 11.2 |

|

| |||||||

| White | 29.6 | 16.3 | 25.1 | 46.8 | 8.6 | 29.7 | 50.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Asian | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 5.3 |

|

| |||||||

| Black | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

|

| |||||||

| None/other | 23.6 | 13.7 | 23.4 | 33.2 | 12.1 | 26.7 | 31.8 |

Our analysis of school data from the California Department of Education (2001–2010).30

Neighborhood income is measured as annual median household income in the census tract where the school was located, and schools are grouped into income tertiles.

Neighborhood education is measured as the proportion of census tract residents ages 25 years and older with 16 or more years of education, and schools are grouped into education tertiles.

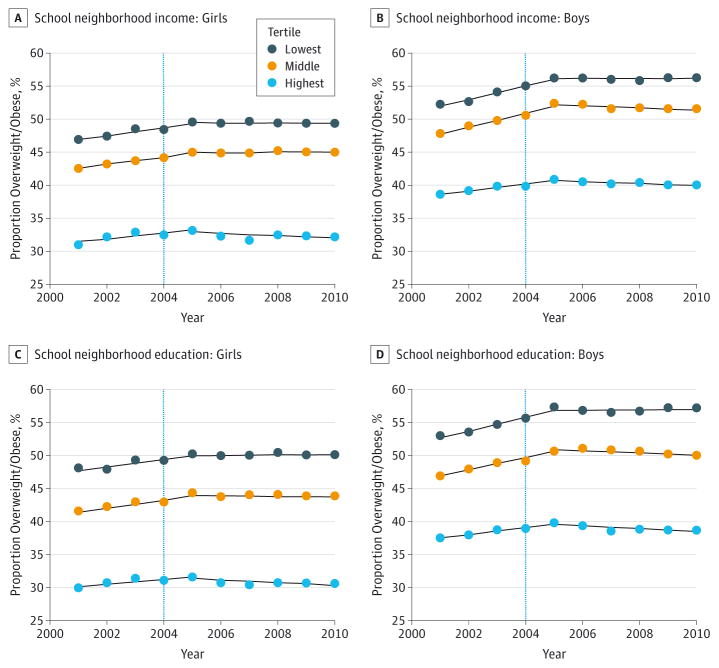

Among all fifth-grade children (Table 1), the prevalence of overweight/obesity was slightly higher each year from 2001 and 2005 and stabilized thereafter. Each year from 2001 to 2010, the prevalence of overweight/obesity was highest among students attending schools in the least-advantaged neighborhoods and lowest among those in the most socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods (Table 1 and Figure 1). Results for obesity were similar (eTable and eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Observed Overweight/Obesity Prevalence by School Neighborhood Income and Education Levels and by Sex.

Neighborhood income was measured as annual median household income in the census tract where a school was located; schools were grouped into income tertiles. Neighborhood education was measured as the proportion of school census tract residents who were ages 25 years and older and had 16 or more years of education; schools were grouped into education tertiles. Data are from Fitnessgram 2001–2010 for fifth-grade students linked with school, district, and 2000 Census data. The vertical line denotes the effect date of the beverage policy (2004); the nutrition policy went into effect in 2007.

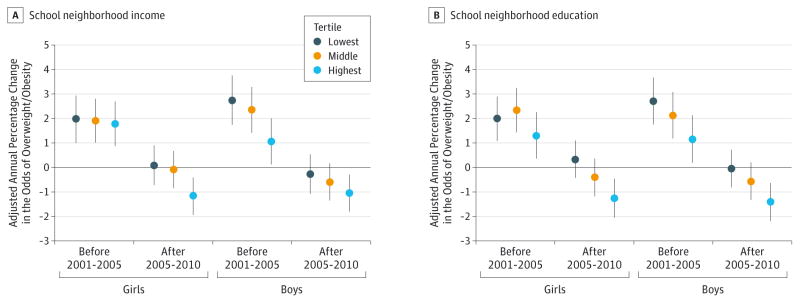

These patterns persisted after adjusting for differences in student-, school-, and district-level characteristics. Figure 2 shows estimates of the trends in the odds of overweight/obesity (and thus trends in prevalence) by school neighborhood income and education tertiles and by sex for the prepolicy and postpolicy periods. In the prepolicy period, there was a significant upward trend in childhood overweight/obesity prevalence among all tertiles of school neighborhood income and education. After CF&B policies took effect, all groups had significant improvements in the trends (slope) of child overweight/obesity prevalence (P < .05), regardless of income and education tertiles and sex.

Figure 2. Adjusted Percentage Change in the Odds of Overweight/Obesity Per Year Comparing the Periods 2001–2005 and 2005–2010 by School Neighborhood Income (A) and Education (B) Levels and Sex.

The positive (negative) percentage change implies the prevalence is increasing (decreasing). After the competitive food and beverage policies took effect in elementary schools, only children attending schools in high-income or high-education neighborhoods demonstrate a decreasing overweight/obesity trend. Percentage changes are based on a multilevel logistic regression model, adjusted for age; race/ethnicity; fitness levels; and school-level enrollment, racial/ethnic composition, and proportion of children eligible for free or reduced-price meals. Models by neighborhood income additionally adjust for continuous neighborhood education; models by education additionally adjust for continuous income. Data are from Fitnessgram 2001–2010 on fifth-grade students, linked with school, district, and 2000 Census data. The error bars indicate 95% CIs.

However, in the postpolicy period, overweight/obesity prevalence trends differed significantly by school neighborhood income and education tertiles (P = .04 and P = .01, respectively) among girls and by education tertiles among boys (P = .03) (Figure 2). Among male and female students in the bottom 2 tertiles of school neighborhood income, overweight/obesity trends were essentially flat; for example, the annual percentage change in overweight/obesity odds was 0.1% for females (95%CI, −0.7 to 0.9) and −0.3% for males (95% CI, −1.1 to 0.5) (Figure 2). In contrast, trends declined significantly among students attending schools in socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods (P < .001). In the highest-income neighborhoods, the annual percentage decline in the odds of overweight was 1.2% for females (95% CI, 0.4 to 1.9) and 1% for males (95% CI, 0.3 to 1.8) (Figure 2). The flat trend in overweight/obesity among students in schools in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods differed significantly from the declining trend among children in the most socioeconomically advantaged school neighborhoods (P < .05 for all except income among boys). Results were similar for school neighborhood education when obesity was used as the outcome (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We examined pre– and post–CF&B policy trends in the prevalence of overweight/obesity among California fifth-grade students by school neighborhood advantage. In the prepolicy period (2001–2005), the trends in childhood overweight/obesity increased significantly for students at all levels of school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage. After the CF&B policies took effect (2006–2010), the trends appeared to level off among students in the lowest and middle tertiles of school neighborhood advantage but declined significantly among students in the highest tertiles. The observed changes were similar for girls and boys.

Unlike previous research,18,23,31,32 to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine trends in overweight/obesity prevalence and changes in trends associated with the timing of CF&B policies by levels of school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage. Policies governing school meal nutritional content and CF&Bs have been associated with lower BMI z scores and reduced likelihood of overweight or obesity among elementary and middle school students15,23,32 and among middle school boys,33 although some studies have found mixed results among certain subgroups.23,33,34 Evidence from a previous study suggested a plateau in obesity nationwide during 2003–2004 and 2011–2012 among 6- to 11-year-old children,31 although trends in overweight/obesity prevalence within or across socioeconomically diverse school neighborhoods were not examined.

This study adds evidence suggesting that CF&B policies are associated with improvements in overweight and obesity trends among younger students in elementary schools regardless of school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage. However, in the postpolicy period, the magnitude of improvements depended on levels of school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage. These findings suggest that the influence of CF&B policies on childhood overweight/obesity trends and disparities in trends is likely to depend on school neighborhood context (ie, features of the built environment and socioeconomic conditions surrounding schools). For example, research has found clustering of fast food restaurants near schools35 and linked those with child BMI levels.36 It is possible that variations in student access to unhealthy foods in neighborhoods near schools may play a major role in the observed disparities in obesity trends.

This study highlights the importance of investigating the association between CF&B policies and childhood overweight/obesity trends within the context of school neighborhood socioeconomic resources. Future research should identify both the school and neighborhood environments that support or hinder children’s physical activity and healthy eating and their combined influence on childhood overweight/obesity. To accelerate progress in obesity prevention, particularly among children in disadvantaged school neighborhoods, strategically targeted programs and policies are needed including those that govern nutrition, physical education, and school-level interventions and that closely consider environmental factors within and near schools.

The Institute of Medicine recommended that schools provide more than half of the minimum of 60 minutes of moderate to intensive physical activity per day to their students.37 However, research has found that support for physical activity and availability of physical education teachers vary across schools based on socioeconomic resources.38 From 2004 to 2006, most California elementary school children attended schools in districts that were noncompliant with physical education mandates.39 Physical activity resources both in and out of school may be a significant driver of disparities in obesity rates among children in schools located in poor neighborhoods compared with their counterparts in advantaged neighborhoods.

The observed differential influence of CF&B policies on child overweight/obesity trends may also be explained by factors that could affect implementation of and adherence to CF&B policies. Using a relatively small sample of schools, a study found that rates of adherence to CF&B policies in California have increased over time.40 Another study found that California youth have lower intake of fat, sugar, and total calories compared with those in states with no CF&B laws.41 To accelerate progress, funding at the time that the policies are enacted should be allocated for follow-up strategies to ensure that CF&B policies are fully implemented and adhered to in all schools; these could include periodic evaluations and on-site monitoring. The new US Department of Agriculture standards for CF&Bs could help reduce the substantial overweight/obesity disparities by school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage observed in this study.

Limitations of this study included the lack of randomization of student exposure to the CF&B policies. Because the policies went into effect at the same time at schools statewide, our findings may have been confounded by temporal trends in overweight that were not related to the policy changes or measured covariates in this study.28 Similarly, we could not examine the extent to which the observed changes in overweight/obesity trends in California may have been influenced by national and other state-specific policies. Although we were unable to clearly distinguish the separate impacts of the food and beverage policies on overweight/obesity trends, both are likely to have contributed to the trend changes we observed.

Lack of data on variation in the implementation of the policies across schools and therefore students’ actual exposure to them precluded us from assessing a dose-response relationship between the new policies and overweight/obesity trends. We were also unable to control for student-level socioeconomic factors, which were unavailable in the Fitnessgram testing, although we did examine school-level eligibility for free or reduced-price meals as well as income and education levels in school neighborhoods. We could not control for physical activity outside of school but did adjust our findings for student physical fitness levels from Fitnessgram data as an indicator of successful physical activity. Despite these limitations, we studied more than 2 million fifth-grade students nested in public schools and their respective neighborhoods and school districts statewide.

Conclusions

Our study findings point to significant improvements in child overweight/obesity prevalence trends associated with the timing of CF&B policies for all fifth-grade students, regardless of school neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics. However, this study also found that improvements in overweight/obesity were stronger among children attending schools in socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods relative to their counterparts in disadvantaged neighborhoods. These findings suggest that CF&B policies may be crucial interventions to prevent child obesity but the degree of their effectiveness is also likely to depend on influences of socioeconomic resources and other contextual factors within school neighborhoods. To reduce disparities and prevent childhood obesity among all children, school policies and environmental interventions must address relevant contextual factors in neighborhoods surrounding schools.

Supplementary Material

At a Glance.

The purpose of this research was to investigate whether the association between competitive food and beverage policies and childhood overweight/obesity trends in California differed by school neighborhood income and education levels.

Irrespective of school neighborhood income or education levels, overweight/obesity prevalence trends increased significantly among all fifth-grade students in the period prior to the policies (2001–2005).

In the postpolicy period, overweight/obesity prevalence trends differed significantly by school neighborhood income and education levels, controlling for student-, school-, and district-level characteristics.

From 2005–2010, trends in the prevalence of overweight/obesity leveled off among students attending schools in more disadvantaged neighborhoods but declined significantly among students at schools in neighborhoods with the highest income and education levels.

Competitive food and beverage policies may be crucial interventions to prevent child obesity but the degree of their effectiveness is likely to depend on socioeconomic and other contextual factors in school neighborhoods.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Sanchez-Vaznaugh received salary support from grant K01HL115471 from the National Institutes of Health and Dr Sánchez received salary support from grant 1-P01-ES-022844-01 from the National Institutes of Health, grant 69599 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and grant 83543601 from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Supplemental content at jamapediatrics.com

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author Contributions: Drs Sanchez-Vaznaugh and Sánchez had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Sanchez-Vaznaugh, Sánchez.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Sanchez-Vaznaugh, Sánchez.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Sánchez.

Obtained funding: Sanchez-Vaznaugh, Sánchez.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Crawford.

Disclaimer: The content in this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding institutions.

Additional Contributions: We thank Fumika Matsubara, MPH, and Sahana Vasanth, MPHc (San Francisco State University), for research assistance and Sarah Abraham, BS (University of Michigan), for assistance with statistical analyses. Ms Matsubara and Ms Vasanth received compensation from the National Institutes of Health. Ms Abrams conducted initial statistical analyses as part of her academic studies; she did not receive compensation from a funding sponsor.

References

- 1.US Government Accounting Office. [Accessed May 4, 2008];School meal programs: competitive foods are widely available and generate substantial revenues for schools. 2005 http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05563.pdf.

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellis DD. School Meal Programs: Competitive Foods are Widely Available and Generate Substantial Revenues for Schools. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2)(suppl):S91–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox MK, Gordon A, Nogales R, Wilson A. Availability and consumption of competitive foods in US public schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 suppl):S57–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildey MB, Pampalone SZ, Pelletier RL, Zive MM, Elder JP, Sallis JF. Fat and sugar levels are high in snacks purchased from student stores in middle schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(3):319–322. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Story M. Schoolwide food practices are associated with body mass index in middle school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1111–1114. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox MK, Dodd AH, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Association between school food environment and practices and body mass index of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 suppl):S108–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Hook J, Altman CE. Competitive food sales in schools and childhood obesity: a longitudinal study. Sociol Educ. 2012;85(1):23–39. doi: 10.1177/0038040711417011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datar A, Nicosia N. Junk food in schools and childhood obesity. J Policy Anal Manage. 2012;31(2):312–337. doi: 10.1002/pam.21602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed September 22, 2014];Competitive foods and beverages in US schools: a state policy analysis. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/nutrition/pdf/compfoodsbooklet.pdf.

- 12.Boehmer TK, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Dreisinger ML. Patterns of childhood obesity prevention legislation in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy J, Vinter S, Richardson L, Laurent R, Segal L. F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies are Failing America. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food and Nutrition Service, USDA. National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: nutrition standards for all foods sold in school as required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010: interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2013;78(125):39067–39120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chriqui JF, Pickel M, Story M. Influence of school competitive food and beverage policies on obesity, consumption, and availability: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(3):279–286. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larson N, Story M. Are ‘competitive foods’ sold at school making our children fat? Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):430–435. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richmond TK, Subramanian SV. School level contextual factors are associated with the weight status of adolescent males and females. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(6):1324–1330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chriqui JF, Turner L, Taber DR, Chaloupka FJ. Association between district and state policies and US public elementary school competitive food and beverage environments. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):714–722. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein DM, Hill EL, Whitaker RC. School food environments and policies in US public schools. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e251–e259. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner LR, Chaloupka FJ. Student access to competitive foods in elementary schools: trends over time and regional differences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2):164–169. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delva J, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Availability of more-healthy and less-healthy food choices in American schools: a national study of grade, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic differences. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4 suppl):S226–S239. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanney MS, Bohner C, Friedrichs M. Poverty-related factors associated with obesity prevention policies in Utah secondary schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(7):1210–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Sánchez BN, Baek J, Crawford PB. ‘Competitive’ food and beverage policies: are they influencing childhood overweight trends? Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):436–446. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for school health programs to promote lifelong healthy eating. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45(RR-9):1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.California Department of Education. [Accessed September 22, 2014];Physical fitness testing. 2014 http://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/pf/index.asp.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.California Department of Education. [Accessed March 4, 2014];Fitnessgram Healthy Fitness Zones. 2009 http://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/pf/documents/healthfitzone09.pdf.

- 28.French B, Heagerty PJ. Analysis of longitudinal data to evaluate a policy change. Stat Med. 2008;27(24):5005–5025. doi: 10.1002/sim.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuels SE, Hutchinson KS, Craypo L, Barry J, Bullock SL. Implementation of California state school competitive food and beverage standards. J Sch Health. 2010;80(12):581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.California Department of Education. [Accessed December 1, 2008];Student and school data files. http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sd/sd/

- 31.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Perna FM, Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Weight status among adolescents in States that govern competitive food nutrition content. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):437–444. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, et al. Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial in middle schools. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riis J, Grason H, Strobino D, Ahmed S, Minkovitz C. State school policies and youth obesity. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(suppl 1):S111–S118. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austin SB, Melly SJ, Sánchez BN, Patel A, Buka S, Gortmaker SL. Clustering of fast-food restaurants around schools: a novel application of spatial statistics to the study of food environments. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1575–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis B, Carpenter C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):505–510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institute of Medicine. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson JA, Mignano AM, Norman GJ, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in elementary school practices and children’s physical activity during school. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28(3 suppl):S47–S53. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130430-QUAN-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Sánchez BN, Rosas LG, Baek J, Egerter S. Physical education policy compliance and children’s physical fitness. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodward-Lopez G, Gosliner W, Samuels SE, Craypo L, Kao J, Crawford PB. Lessons learned from evaluations of California’s statewide school nutrition standards. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2137–2145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.193490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Differences in nutrient intake associated with state laws regarding fat, sugar, and caloric content of competitive foods. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(5):452–458. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.