Abstract

Despite growing male participation in ending violence against women, little is known about the factors that precipitate men's engagement as antiviolence “allies.” This study presents findings from a qualitative analysis of interviews with 27 men who recently initiated involvement in an organization or event dedicated to ending sexual or domestic violence. Findings suggest that men's engagement is a process that occurs over time, that happens largely through existing social networks, and that is influenced by exposure to sensitizing experiences, tangible involvement opportunities and specific types of meaning making related to violence. Implications for models of ally development and for efforts to engage men in antiviolence work are discussed.

Keywords: ally development, domestic violence, engaging men, prevention, sexual assault

Engaging boys and men as antiviolence allies is an increasingly core element of efforts to end violence against women. In the past decades, men have become more of a presence in long-established domestic and sexual violence organizations and have created myriad men's organizing groups aimed at educating, engaging, and mobilizing other men to take an active stand against sexual and intimate partner violence. Based in the reality that the majority of perpetrators of violence are male (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998), that risk for violence is connected to traditional notions of appropriate “masculinity,” (Heise, 1998; Murnen, Wright, & Kaluzny, 2002), and that men are more likely to be influenced by other men (Earle, 1996; Flood, 2005), there is increasingly widespread agreement that the project of ending domestic and sexual violence requires male participation (Flood, 2005; DeKeseredy, Schwartz, & Alvi, 2000). Existing programs engage males in a continuum of involvement, ranging from raising men's awareness about violence against women to encouraging their active involvement in taking a stand against the abuse of women (being an “ally”). Examples include The Men's Program, a prevention intervention for men that has been shown to reduce rape-related attitudes and behaviors among some college students (Foubert, Newberry, & Tatum, 2007); Mentors in Violence Prevention (Katz, 1995); and Men Can Stop Rape's Men of Strength Clubs (Hawkins, 2005), ally-building programs considered “promising” prevention strategies (Barker, Ricardo, & Nascimento, 2007).

Still, knowledge building regarding men's antiviolence work is in its early stages. In particular, little data exist on the routes through which men initiate involvement in anti-violence efforts or come to define themselves as antiviolence “allies.” In addition, although theorizing has developed regarding ally building in other social justice endeavors such as antiracism work, theoretical frameworks relative to men's antiviolence engagement are relatively new. Enhancing this knowledge and theory base holds promise for expanding outreach efforts to diverse men and for understanding how best to engage them. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to summarize research and theory regarding the process of initially engaging men, to present findings from a study of male allies about their involvement in antiviolence work and to evaluate the degree of congruence between these men's experiences and existing theoretical perspectives on ally development.

Models of Social Justice Ally Building

Engaging men as partners in efforts to end violence against women can be seen as parallel to “ally” development in other social justice arenas. Allies are typically defined as “members of dominant social groups (e.g., men, Whites, heterosexuals) who are working to end the system of oppression that gives them greater privilege and power based on their social-group membership” (Broido, 2000, p. 3). Significant model-building work describing the processes of ally building has occurred, particularly in relation to the development of anti-racism allies. These models are likely instructive for enhancing theorizing and practice relevant for engaging men, particularly as many male allies may see their role as working to dismantle multiple forms of oppression (Funk, 2008) and because violence itself is inextricably linked with mechanisms of oppression (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005).

Models of social justice ally formation are typically developmental in nature, noting the factors over time that collectively shape an individual's awareness of and commitment to rectifying social inequities. Across these models, critical elements of ally development include learning experiences regarding issues of racism and social inequity coupled with ongoing opportunities to process, discuss, and reflect on those experiences (Broido, 2000; Reason, Miller, & Scales, 2005) and opportunities to experience being a “minority” or to examine the parts of one's personal identity that are marginalized by “dominant” groups (Bishop, 2002; Reason et al., 2005). Specific invitations to participate in social justice work and modeling by respected peers or mentors is also important (Reason et al., 2005; Tatum, 1994). Finally, many models of social justice ally development highlight the central importance of developing self-awareness of personal sources of unearned social privilege in relation to other groups (Bishop, 2002; Reason et al., 2005; Tatum, 1994) Drawing on social identity theory, such as Helms' (1990) theory regarding White racial identity development, these models suggest that ally behavior is predicated on a “status” of identity development characterized by the acknowledgment of racism and other forms of social inequities, coupled with an awareness of how one's own privilege may be complicit in the marginalization of others. Taken together, these models highlight the multilayered nature of ally-promoting dynamics, which include intrapersonal factors (such as the ability to critically self-reflect), interpersonal factors (opportunities to engage with others across racial or gender “difference”), and environmental factors (concrete opportunities for involvement). These factors are likely highly applicable to male antiviolence ally development.

Theoretical Perspectives on Engaging Men as Allies

Although empirical models specific to male antiviolence ally formation have not been developed, researchers have proposed applying existing theoretical frameworks, such as cognitive behavioral theory and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), to violence prevention and ally building efforts. For example, Crooks and colleagues (Crooks, Goodall, Hughes, Jaffe, & Baker, 2007) suggest that the cognitive behavioral principles of surfacing and reshaping an individual's core beliefs about an issue, identifying specific behaviors that build toward a desired behavior, and building opportunities to practice new behaviors could address common barriers to men's antiviolence involvement, such as ambivalence about the seriousness or relevance of the topic of violence against women and uncertainty about or lack of skill related to specific actions they can take.

Similarly, scholars argue that principles from the TTM are instructive in tailoring violence prevention and ally-building efforts (Banyard, Eckstein, & Moynihan, 2010; Berkowitz, 2002). A stages of change model, the TTM suggests that individuals occupy different statuses in terms of their readiness to engage in behavior change over time and that intervention strategies should be matched to an individual's current change stage (Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2002). Applying the model to a bystander-focused sexual assault prevention program, Banyard et al. (2010) found that participants' preintervention stage of awareness regarding sexual assault (ranging from denial of the problem to active involvement in prevention activities) was associated with the magnitude of the program's impact on the participants, with respondents in the “precontemplation” stage evidencing less change following the program. Although applied to a mixed-gender audience in this case, these findings suggest that the TTM can offer a helpful framework for thinking about differentially tailoring engagement efforts for men with different levels of awareness or concern for the issue of violence against women. This concept is echoed in previous conceptualizations of men's degree of engagement, such as Funk's (2006) “continuum of male attitudes toward sexism and sexist violence” (p. 78) that ranges from “overtly hostile” to “activist” in describing men's possible orientations to the issue of violence against women. To date, however, the implementation of either cognitive behavioral or TTM principles in engaging male allies has not been expressly tested, nor do these models necessarily address the combination of internal or environmental precipitating factors that might motivate men to seek or avoid an opportunity to learn about the issue of violence against women in the first place.

Factors Associated With Men's Antiviolence Involvement

From the handful of studies that have explicitly examined factors associated with men's involvement in antiviolence or gender equity efforts, three themes are apparent. First, exposure to or personal experiences with issues of sexual or domestic violence appear to be a critical element (Coulter, 2003; Funk, 2008). Second, receiving support or encouragement from peers, role models, and specifically, female mentors is associated with initiation into antiviolence efforts (Coulter, 2003). This theme of peer support is echoed in findings that men's willingness to intervene in sexist peer behavior or a situation that may lead to violence against a woman is related to men's perceptions of their male peers' willingness to do the same (Fabiano, Perkins, Berkowitz, Linkenbach, & Stark, 2003; Stein, 2007). Finally, longer term dedication to antiviolence work is associated with employing a social justice analysis of violence that includes issues of racism and homophobia and that links violence against women to sexism (DeKeseredy et al., 2000; Funk, 2008).

Although these findings suggest that peers, mentors, and an awareness of violence or other social justice issues constitute a few of the possible important building blocks that support men's entrée into antiviolence involvement, little is known about the particular ways that these factors influence men. Other possible pathways in the probably complex process involved in deciding to join an antiviolence effort are also not yet elucidated. Furthermore, unlike more general models of social justice ally development, the degree to which social identity development and an awareness of male privilege are central to initial antiviolence ally formation is unknown. Although some approaches to engaging men in antiviolence work incorporate a focus on critically examining notions of masculinity, such as Men Can Stop Rape's focus on “re-storying” dominant narratives of manhood (www.mencanstoprape.org), the extent to which male antiviolence involvement is predicated on a critical awareness of male privilege remains unclear. As a whole, the specific factors influencing men's pathways to involvement have been identified by practitioners and current male allies as topics ripe for future research and investigation (e.g., Funk, 2008).

Summary and Purpose of the Study

In summary, although models of ally development have emerged from more general social justice arenas, the accuracy of these models in describing men's experiences of initiating antiviolence involvement is unknown. Furthermore, little data are available regarding the specific internal, interpersonal, and environmental factors that mutually facilitate men's antiviolence participation. Elucidating these gaps holds promise for more effectively reaching out to men and fostering their positive involvement in ending violence. To this end, this study examines qualitative data from interviews with 27 men who recently initiated membership or involvement in an anti-sexual or domestic violence effort. Specifically, this study aims to (a) describe the pathways through which these men became involved in antiviolence efforts, (b) build a conceptual model of participants' initiation into antiviolence work, and (c) evaluate the degree of overlap between extant theorizing about social justice ally development and the participants' descriptions of their own experiences.

Method

Participant Recruitment

In accordance with procedures approved by the human subjects review committee, potential respondents were recruited in four ways. First, notices about the study were disseminated via several topic-relevant national email listserves, including the Prevention Institute's sexual violence prevention listserve and the Men Against Violence listserve on Yahoo. Permission to forward these notices to other relevant interest groups was included. Second, the first author attended relevant local community or agency meetings to announce and disseminate information about the study. Third, leaders of local men's antiviolence organizing groups were contacted and provided with information about the study. Finally, men who contacted the researcher regarding participation were invited to refer other potentially eligible men. Respondents contacted the researcher directly and were screened for eligibility. Participation eligibility criteria included initiating involvement in an antiviolence against women organization, event, or group within the past 2 years at the time of contacting the study and being a man 18 years or older. Consistent with the goals of the study, recent initiation into antiviolence work was included as an eligibility criterion to assess current factors and strategies associated with men's involvement; some data on factors associated with long-term antiviolence activism already exist (e.g., Funk, 2008). Eligible participants were then scheduled for a phone or in-person interview, depending on location.

Sample

A total of 43 men were screened for participation in the study. Fourteen described long-term antiviolence involvement and were therefore ineligible for participation. An additional two men did not return consent forms and therefore could not be interviewed. The final sample consisted of 27 men, aged 20 to 72. All but one identified as White; one man identified as Latino. This article, therefore, largely reflects the experiences of White men in coming to view the issue of violence as relevant to and actionable in their own lives. Of the 16 men whose length of participation or lack of consent form excluded them from the study, 5 identified as African American, 1 as Latino, and 10 as White. Participants from locations across the United States were recruited and represented all regions of the country. Length of involvement in antiviolence work at the time of the interview ranged from 1 to approximately 30 months.

Participants' involvement in antiviolence work generally fell into two categories: employment/volunteer work or involvement in a college campus-based organization. Of the 27 men, 10 (37%) were postcollege-aged men who worked or volunteered with a domestic and/or sexual violence-related program or government agency. These men's roles ranged from doing direct advocacy with survivors of violence to volunteering in a prevention education program for youth. Of these, 5 reported that part of their organizational role was to engage other men or boys around the issue of violence. Sixteen (59%) of the participants (aged 20-42) joined a campus-based antiviolence group or effort at the college or university in which they were enrolled. Typical activities in which these participants were engaged included facilitating educational presentations for other college students, organizing campus-wide antiviolence awareness events, or designing activities or events aimed at garnering additional male participation. Finally, one participant described his participation as being a part of a men's discussion group that had partnered in fundraising efforts with a local domestic violence agency.

Data Collection

Nine participants were interviewed in person and the remaining 18 were interviewed by phone. Interviews varied from 45 to approximately 90 min in length and were semistructured, with standardized general questions designed to elicit involvement narratives, followed by tailored follow-up questions to explore relevant issues in greater depth. Question topics included the nature of men's involvement; the factors precipitating their initiation into antiviolence work; their perceptions of effective and ineffective strategies for engaging other men; the impact of antiviolence involvement on their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors; and their perceptions of the factors that sustain men's antiviolence efforts. For example, men were asked to describe what prompted them to become involved in their organization or event, followed by in-depth prompts to expand on any personal and/or environmental influences. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Grounded Theory techniques and principles (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). An inductive analysis strategy useful for building conceptual frameworks from data, Grounded Theory, emphasizes the development of conceptual categories derived through constant comparison of the dimensions of analytic concepts emerging from participants' data. Analysis was conducted by two researchers using the qualitative analytic software program ATLAS.ti. Coding was initially done separately by each researcher on several transcripts and then compared and negotiated until agreement was reached on categories in the data for the purposes of analyzing remaining transcripts. Coding proceeded in two phases. First, all transcripts were coded for general domains, with like domains pertaining to men's pathways to involvement grouped together. Second, close inductive coding on relevant domains was done using extensive memoing to uncover concepts within the data and relationships between those concepts. Particular attention was paid to the dimensions and qualities of the factors reported by participants as salient to their initiation into antiviolence involvement. Once saturation of concepts was reached, all transcripts were reread and compared for both confirming and disconfirming cases. When agreement between researchers was reached regarding concepts and their theoretical relationships, trustworthiness was enhanced through the use of six member checks (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and through third-party checks by two independent readers who evaluated the face validity of concepts and the data used to support them.

Results

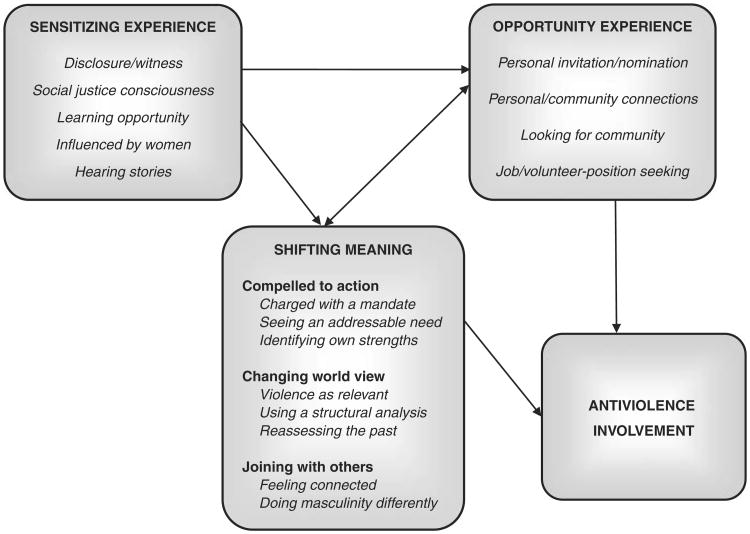

Participants' descriptions of the specific factors related to their antiviolence involvement fell into three arenas. These arenas and the proposed relationships between them are summarized in Figure 1. First, all men but one had some sort of “sensitizing” or priming experience that raised their level of consciousness regarding issues of violence or gender inequity and seemed to lay the groundwork for being open to involvement when an opportunity arose. Second, all men had at least one tangible opportunity or entrée into an antiviolence group, volunteer opportunity, or job. Third, the meaning that participants had come to attach to the initial sensitizing and/or to the opportunity experience seemed to be a critical component of men's decision to devote time to antiviolence work. In other words, the impact of a sensitizing or opportunity experience or the particular ways men made sense of it, constituted the motivating factor that allowed men to take or seek an opportunity to get involved. Pathways of men's movement through these arenas are reflected in Figure 1 and described more fully below.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of men's pathways to antiviolence involvement.

Sensitizing Experiences

Most men identified more than one previous experience that rendered the issue of violence against women more salient or visible. The sensitizing experience may have made the issue of violence more important or “real” and was the first influential involvement factor for 25 (92%) of the participants. One participant did not describe any sensitizing experiences, and a second participant encountered a sensitizing experience after his first involvement opportunity. The most common sensitizing experience was hearing a disclosure of domestic or sexual violence from a close female friend, family member, or girlfriend or witnessing violence in childhood. Fifteen respondents (56%) reported exposure to violence or a disclosure of violence, and many of these participants described reevaluating the meaning of that exposure over time or as other sensitizing or opportunity incidents arose. Next, 8 respondents (30%) described a preexisting social justice consciousness or egalitarian value system as a factor in sensitizing them to issues of men's use of violence. This often stemmed from a respondent's own experiences of marginalization or from previous exposure to connected issues of racism, classism, and sexism. Another 8 respondents (30%) reported that they were exposed to a specific learning opportunity related to violence against women. For most of these men, this learning was a college-based prevention presentation on dating violence or sexual assault. Others were exposed to content through courses or lectures. Five participants (18%) reported that close relationships with influential women (mostly mothers) made them more aware of threats to women's safety or fostered a feminist consciousness. Finally, 4 participants (15%) reported that they had been moved or troubled by a story or stories of violence survivors who were not personal acquaintances of the men. These stories emerged in a variety of contexts, including church, a work-related setting, and Take Back the Night marches.

Opportunity Experiences

Similar to their sensitizing experiences, many men encountered more than one tangible entrée into antiviolence involvement. Nine respondents (33%) were formally invited or nominated to become a part of an antiviolence group or event by an acquaintance, professor, or supervisor. Seven (26%) of the participants were members of a friendship group or community in which others who were involved in antiviolence work encouraged the respondent to come to a meeting or communicated that participation was important, inspiring, or fun. Ten men (37%) reported that they were looking for a group, a “way to make a difference” or a community of similarly minded friends and that this active search precipitated involvement. Most of these men also knew someone involved in the group or effort that they ultimately joined. Finally, 5 participants (18%) initiated antiviolence work as the result of a job or volunteer position search. For 2 men, a formal involvement opportunity was the first influential factor precipitating their participation in some kind of antiviolence effort.

Shift in Meanings

As men discussed the nature and qualities of the experiences that led to their antiviolence involvement, they described specific meanings they had derived from these experiences. For 17 of the men, a meaning evolved over time from a sensitizing event, which then became a precipitate or motivating factor in seeking or accepting an opportunity to become active. For the remaining 10 participants, the meanings emerged following a tangible involvement opportunity, which often generated new reflection on earlier sensitizing experiences or exposure to additional sensitizing events. This new meaning making in turn precipitated accepting an offer to join an antiviolence effort or prompted the respondent to seek one. In both cases, the meaning that men attached to their sensitizing and opportunity experiences appeared to be a critical motivating factor in involvement. Three primary meanings surfaced, each with subthemes, and most men identified with more than one meaning. These are described more fully below.

Compelled to Action

This group of three subthemes was generally related to a sense of feeling obligated to take action or seeing a tangible opportunity for making a difference. Collectively, men who derived these meanings from their sensitizing or opportunity experiences felt that they no longer had a choice to do nothing, newly perceived doing nothing as contributing to the problem, or had a clear sense of how their own strengths could make a contribution to addressing violence.

Charged with a mandate

The first of these subthemes, “charged with a mandate,” was reported by 9 participants (33%). These men reported a sense that their new knowledge or awareness of violence rendered them responsible for taking action. Several men felt that having this knowledge eliminated the option of being uninvolved or of not speaking up as long as women's safety was jeopardized. For example, the following respondent reflected on how his growing understanding of sexual violence led him to equate inaction with acquiescence and deepened his commitment to taking an active antiviolence stance:

Instead of seeing isolated incidences of people that I knew who had been assaulted, [I] started looking at that as a systemic issue. And I think once I started doing that, it was like, okay, how can I not? … And I think I started putting that together … that it's a generalizable experience. Even people who haven't been assaulted experience some of this fear. I just knew what side of that I wanted to be on, and I knew that … not being active about it was being silent about it, and, therefore, in a sense condoning it. (MAV27)

Other men reported an increased awareness that simply not using violence in their own lives and being “decent” was not sufficient to reduce violence or to maintain the safety of women they care about. Describing the meaning he derived from a campuswide presentation, one participant stated,

The thing that Jackson Katz was talking about is that, you could say, we're all good men here because we don't hit our girlfriends or wives, but he was saying, “Well, that's not good enough. You've got to be better men.” And so that kind of inspired me. (MAV9)

Perceiving an addressable need

The second subtheme under the meaning “compelled to action,” was “perceiving an addressable need,” reported by 6 respondents (22%). The meaning is characterized by men's perception that violence against women is a problem that can be addressed or made tangibly better, perhaps more so than other social issues, as reflected in this respondent's statement, “I can't stop global warming tomorrow, and I can't stop poverty tomorrow, but tomorrow someone might not get hit” (MAV4). Other men got involved because they identified or were exposed to a specific need or to a contribution they could make. The following participant described the appeal of a full-time role in an antiviolence agency:

I feel like I'm making a difference on a day-to-day basis by changing and/or having people listen to the story of the women. … Or the other day I got funded for a grant that I wrote. … And to get that notice in the mail saying we want to support what you're doing, you know those things are just huge for me. And I just feel like I'm making a difference every day. (MAV6)

Identifying own strengths

Finally, 5 respondents (18%) noted that the sensitizing or opportunity experience had the effect of highlighting or identifying a particular skill or quality in them that was needed. As a result, these participants felt that they had something specific to contribute, or felt trusted, honored, or recognized by encouragement to participate or by a disclosure from a survivor. Describing his reaction to a friend's disclosure of abuse one participant noted,

I don't know if I knew the full power or the level of trust that's involved in telling someone else this, but I remember feeling really glad or good that she could trust me enough to say that … and that made me want to do that more. (MAV20)

On receiving a nomination to join an antiviolence education group, another participant learned about how his own skills could be tangibly useful, which motivated him to pursue the involvement opportunity:

I went through the interview process, you know I found out that the work they do was very presentation based, and I consider myself a very strong public speaker who's talking to a lot of male populations, or all male populations … and I thought that I could be a good, forceful speaker and really have a helpful role in trying to communicate with these populations. (MAV7)

Changing Worldview

As a result of processing their sensitizing or opportunity events, several respondents reported experiencing a deep shift in their thinking about their own experiences or behavior or in their level of comprehension of the ongoing vulnerability of women. This shift often served to connect the issue of violence much more closely to their own reality or priorities, or foster a previously absent emotional connection to the issue. Three subthemes also emerged in relation to the “changing worldview” meaning.

Violence as relevant

First, 11 respondents (41%) reported a heightened awareness of the relevance of violence to their own lives, and particularly to lives of women they care about. Participants described feeling frightened, disturbed, or suddenly conscious of the multiple ways that violence against women manifests in their own communities. For many participants, disclosures of or learning opportunities about violence had the impact of splintering assumptions that violence is not a significant issue in circles close to them. For example, one participant described the magnitude of the impact of learning that his mother is a survivor of violence:

To be completely honest, I really didn't think sexual assault was a very pertinent issue for me as a man until about my sophomore year. And, frankly, like probably until my sophomore year of college … I probably would have argued about the whole one in four statistic and other things like that. Like I never thought sexual assault was a big problem on our University. And during a break I went home and found out through an argument that my mom and sister were having that my mom was actually a victim and survivor of sexual assault. And it really kind of turned my whole … my world over. (MAV12)

For many men, processing a sensitizing experience created a sudden awareness of ongoing vulnerability of people they love and generated an emotional connection to the issue of violence that was previously absent. This emotional connection in turn seemed to lay the groundwork for antiviolence involvement for these participants.

Employing a structural analysis was the second subtheme related to a changing worldview. Eight respondents (30%) reported that as they gained greater exposure to the issue of violence against women, they began to see it as connected with other social justice issues to which they were already committed. Linking sexual and domestic violence to social issues about which they had a preexisting concern, such as racism or homophobia, rendered the issue of violence against women more pressing or relevant. In making these connections, men felt that they could address larger issues of oppression by becoming involved in antiviolence efforts. For example, the following respondent employed an analysis in which he connected violence to two issues he cared deeply about, oppression and environmentalism, both of which he viewed as related to systems of domination and alienation:

And so when I work on the issue of sexualized violence, I'm conscious that I'm working specifically on the issue of sexualized violence, but I'm also conscious in that in working on that issue of sexualized violence, I'm also working on the general issue of violence itself and even more generally on that relationship between self and other, and if I can contribute toward undoing sexualized violence, then I see that as a contribution towards environmentalism, too. (MAV24)

For other respondents, employing a structural analysis was related to linking violence against women to other forms of oppression that they had experienced or witnessed in their own lives. Again, making this connection with personal experiences of marginalization rendered violence a more focal, “actionable” concern for these men:

I saw a lot of my friends growing up experience hate crimes and experience physical violence. … And so I guess I just … I was thinking about how I wanted to be as an ally to women in general. So I think that the way that I got involved in doing anti-violence work was through a lot of the anti-oppression work that I was doing when I was a youth. … I mean I started doing a lot of activism and stuff when I was 14, and you know I've been doing it pretty consistently since then. And so I think that my strong relationship to doing anti-oppression work really helped segue me into doing anti-violence work. (MAV 15)

In addition to the 8 respondents who identified a preexisting social justice consciousness or concern for social equality as a precipitating factor in their involvement, an additional 8 men spoke about how their antiviolence work has subsequently helped them form an analysis of violence that links it to social inequity in general, and patriarchal norms or “traditional” forms of masculinity in particular. These men explicitly made connections between violence against women and issues of sexism, male privilege, and race or sexuality-based oppression. In contrast, 8 men made no overt linkage between violence against women and broader issues of gender inequity or male privilege. Finally, 3 men could be characterized as beginning the process of examining how gender inequities are related to violence.

Reassessing the past

Finally, 4 respondents (15%) spoke about how their sensitization or opportunity experiences led them to reevaluate past experiences or behavior. For these men, new learning about or new exposure to violence sparked additional reflection on past experiences, and perhaps viewing those experiences in a new way. The following 2 men spoke specifically about how their exposure to survivors of violence triggered a reassessment of past aggressive behavior that ultimately motivated antiviolence involvement.

I guess I felt I sort of owed it to myself, if not society, and the universe to balance out who I used to be … so when this thing happened in high school, you know the accused … we literally kicked him out of our lives. And while I don't necessarily regret it, I do realize that is was ultimately probably not productive. And he probably went on to be a rapist or an abuser. He's probably more likely to turn out that way because of what we did. And so in a way it's like … sort of coming into my adulthood with this stuff, you know, I'm wanting to balance out the stupid, vigilante, adolescent emotions around this issue with adult proaction. (MAV3)

My part in DV work is part of my redemption, a part of reconciliation with my violent past. Not guilt or shame, but redemption. (MAV31)

Reevaluating past responses to disclosure was also part of reassessment for two respondents. For these men, new learning about violence against women prompted uneasiness about the way they had handled past situations and motivated a desire to gain the knowledge and skills to provide support to survivors.

In my senior year, the girl I was dating was actually sexually assaulted [by someone else], and there was a lot of gray in the sense that I didn't really recognize fully what had happened at the time. … I was really affected by that, and I felt very powerless. You know, I wasn't able to help her. I certainly blame myself a little bit for not realizing what had happened when it initially did. (MAV2)

Joining With Others

The third major meaning to emerge from men's sensitizing or opportunity experiences was a realization that antiviolence work was an opportunity to enact their own ideals with like-minded others or was a way of joining a compelling group that offered connection and support. Two subthemes are related to joining with others.

Feeling connected

The first subtheme was described by 4 respondents (15%). Primarily through opportunity experiences, these men began to see antiviolence work as a way to build or enhance connection with others, particularly with other men. For these men, involvement was part of building community and a sense of mutual support. This is reflected in the following participant's description of his internal processing following his first exposure to a Take Back the Night event:

Knowing that there was a community of people who cared and in caring, the community substantially contributed to the healing of individuals who were … being so vulnerable, and knowing that there was a community to work with and that we could support each other in this process because something as pernicious and insidious as sexual violence does not just affect individuals; it affects whole communities, and it's all of our burden to bear. And so knowing there was a community willing to stand in the face of that truth and stand together and then say no and then do the work to try and change some things … meant so much to me and made it worthwhile and continues to do so. (MAV13)

Doing masculinity differently

Another 5 participants described the appeal of realizing that they could work with other men in a way that was different from “traditional” approaches to masculinity or male friendship. These men expressed relief or excitement at the prospect of having close friendships with men in which they could express vulnerability, work collaboratively, and find broader ways of “being masculine” than masculine stereotypes might suggest. One participant noted,

It was something about just sitting in a circle with a couple of guys and talking about, you know, how men dance compared to women, like how it's not okay to put your hands above your head when you dance or something [laughs]. Just things like that, that you would never talk about just walking through campus or anything … and I thought that was really unique and really just honest, and it kind of lifts the weight off of your chest. Because I think a lot of the times, men walk around with this shield up, this … or we talk about the male stereotype box that we're always living in. Even if we don't want to, we're still put into that box, and that was the first time in my life where I didn't have that box around me. And I liked it. It was fun. (MAV30)

Discussion

Men's descriptions of the influences that precipitated their involvement in antiviolence work suggest that factors at multiple levels over the course of time coalesce into taking an active stand against violence. Specifically, initial sensitizing exposures to the issue of violence or to survivors, coupled with internal meanings that men attach to these experiences, and tangible involvement opportunities were critical to these men's pathways to engagement. Across these three arenas, four general commonalities characterizing men's antiviolence involvement surfaced. First, all participants described their initiation into active antiviolence participation as a process that unfolded over time and had multiple influences. Men's decision to take a stand against violence against women, attend an event or meeting, or join an antiviolence group was never constituted of or influenced by a single event or factor, but was rather precipitated by a combination of experiences and internal reflection that sparked or deepened men's interest in involvement. Second, respondents described specific ways in which the issue of violence against women had become personalized or emotion laden for them in some way. Their antiviolence involvement was predicated, in part, on discovering ways that violence was personally relevant to their own lives or those close to them or on making an empathic connection with the emotional consequences of violence. Third, the vast majority of participants became involved through or because of existing personal connections and social networks. Finally, many respondents made connections between their involvement and a sense of community; these participants felt that their initiation into antiviolence efforts was supported by their own community or was part of an effort to find or build a sense of community for themselves. Collectively, these findings hold implications both for enhancing model development regarding antiviolence ally development and for the practice of engaging men in violence prevention endeavors. These are discussed in turn below.

Implications for Models of Ally Development

Men's descriptions of their experiences leading to antiviolence involvement evidence both areas of overlap and disconnect with the models of social justice ally development presented in the introduction to this article. Similar to the social justice ally models, antiviolence ally formation was a process that occurred over time, with factors at multiple levels (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community) convening to influence involvement. Specifically, similar to models developed by Broido (2000) and Reason et al. (2005), men's pathways to involvement relied on initial exposure opportunities, engagement in reflection and meaning making over time, personal connections to the issue of violence against women, and tangible, clear invitations or opportunities to join an ally effort within their personal communities. These factors are likely important to retain and adapt in refining models of male antiviolence engagement. Future research could seek to more fully elucidate the mechanisms or intervention approaches that best foster the kinds of precipitating experiences, reflection, and meaning making described by both ally-development models and by men in this study.

A point of departure between models of social justice ally development and the experiences of men in this study is the degree to which male antiviolence allies engaged with their own social identities and male privilege as a precursor to involvement. Although approximately one third of the respondents described linking violence against women to structural justice issues as a meaning that fostered their involvement, this sometimes but not always took the form of interrogating their own social identities, ideas about “masculinity,” or the role of male privilege in perpetuating woman abuse. About one third of men in the study made no explicit connection between violence against women and larger social inequities, such as sexism, even after a period of involvement. Although these men may have framed violence as problematic or people they love as in need of protection, there was an absence of exploration about the roles of gender and power in the perpetuation of woman abuse. Furthermore, only about 15% of the men in the study (those endorsing the “reassessing the past” meaning) explicitly described exploring the ways that their own past or current behavior might have reflected sexism as a step in their process of involvement. Unlike models of ally development more generally, therefore, the degree to which an awareness of gender-based social privilege is (or should be) a necessary prerequisite to antiviolence involvement remains a somewhat open question.

Several possible interpretations of the variance in men's engagement with issues of sexism exist. On a pragmatic level, interview probes may not have been specific enough to prompt all men to reflect on the ways that they engaged with the notion of male privilege as part of their involvement process. It may also be that the nature of many violence-related sensitizing or opportunity experiences (such as hearing a specific survivor's story, or receiving an invitation to attend an antiviolence event) do not contain explicit linkages between abuse and sexism, whereas sensitizing exposure experiences regarding racism or heterosexism likely contain, by their very nature, clear connections to notions of oppression and unearned social privilege.

It may also be that the relatively recent nature of participants' initiation into antiviolence work means that some are at the beginning stages of the process of employing a social justice analysis. The ongoing development of a critical awareness of gender inequity may be fostered by entrance into antiviolence work itself, as it was for about a third of men in this study. Practitioners have noted that initial awareness building and engagement efforts need to meet men “where they are” and that starting with conversations about male privilege may raise defensiveness and deter preliminary participation from some men who have important contributions to make (e.g., Funk, 2006). A the same time, a lack of awareness of male privilege may create risk for recreating patterns of sexism within antiviolence work as more men become involved. Several practitioners have noted the need for men's antiviolence groups to continually consult with and be accountable to women and women's antiviolence networks to ensure that men's prevention efforts honor the considerable history of women's contributions to ending violence and do not replicate structures of inequity (Berkowitz, 2002; Funk, 2006). Although there is likely a middle ground of tailored engagement efforts for men that also gradually work toward a critical understanding of male privilege, the long-term effectiveness of ally efforts depend on tackling gender-based and other social inequities, as these ultimately buttress enduring violence. Further research is needed that examines the impact of involvement in antiviolence work over time on men's analysis of the roots of violence and how men's degree of engagement with issues of sexism and male privilege relates to their impact and effectiveness as “allies.”

Principles from the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) may provide helpful strategies for moving men through the process from a lack of awareness about abuse, to engagement, to a more critical evaluation of sexism and its links to violence against women. Combining social justice ally models with processes identified by the TTM to support behavioral change may enhance both the accuracy and the interventive relevance of these models. For example, Prochaska et al. (2002) identify consciousness raising (increasing an understanding of the causes, impacts, and dynamics of a specific behavior) and environmental reevaluation (examining the impact of inaction or an unhealthy behavior on others) as typical processes associated with moving from denial of a problem to “contemplation,” or a readiness to engage in new behaviors. Coupling these specific processes with initial factors in social justice ally development (such as sensitizing or exposure experiences) may increase the model's explanatory power and guide intervention development related to engaging men around deeper issues of sexism and violence.

Implications for Practice

As noted above, for most of the men in this study, the decision to become part of an antiviolence effort was influenced by multiple factors and occurred over time. Engaging men is a multifaceted process that likely demands repeated and diverse opportunities for exposure to the issue of violence against women as well as built-in mechanisms for men to discuss, reflect on, and make sense of the ways that violence is relevant to their worlds. Previously discussed applications of multiple, diverse strategies for men at different “stages” in their relationship to the issue of violence are needed, both to provide initial “sensitizing” experiences and the opportunities to create meaning from them. For example, large-scale community or educational events might be supported with a network of follow-up conversations, both formally and informally through peer groups, to allow for the kind of processing that could foster men's development as allies.

At the same time, although the men in this study were influenced by many different factors over time, a strong commonality among participants was the importance of personal connections and community in making linkages with concrete antiviolence opportunities. All but 5 participants located an opportunity for involvement through a friend or community member and 9 joined an antiviolence effort as the result of a formal personal invitation. This highlights the primacy of social networks as recruiting and engagement vehicles. Although many study participants were exposed to the topic of violence against women through educational presentations, community events, or college courses, these “learning opportunities” did not directly precipitate involvement on their own. Rather, encouragement and engagement from trusted peers or mentors constituted the tangible involvement opportunity that brought most of the men into antiviolence efforts. This echoes Broido (2000) and Reason et al. (2005) who found that the social justice allies in their studies did not actively seek action opportunities but initiated their social justice activities only after explicit invitations to do so. The project of engaging men and encouraging them to view themselves as allies is therefore perhaps best done individually through existing social networks and by admired peers and necessitates specific, personalized invitations to become a part of the work. Popular Opinion Leader (POL) approaches, which have previously been applied to HIV (Fernandez et al., 2003) and smoking prevention (Campbell et al., 2008), capitalize on the power of natural leaders in existing social networks and may be a relevant approach here. At the same time, engagement through social networks can build on “sensitizing experiences” that many men have likely already had and can foster the kind of meaning making from those experiences that supports antiviolence engagement.

Finally, this “meaning making” is likely central to men's process in coming to see themselves as antiviolence allies. Efforts to provide sensitizing experiences (such as learning opportunities or occasions to hear survivor stories) or to engage men through personal contact in their social networks may be bolstered by explicitly cultivating the kinds of meanings that men in this study came to attach to the issue of violence. These might include unambiguously issuing a charge of responsibility to addressing the issue, identifying specific needs and the ways that individual men's strengths and talents may contribute to ameliorating those needs, fostering connections with supportive groups or community, relaying the unacceptability and dangers of inaction, making explicit linkages between violence and other social issues men may care about, and highlighting the experiences of violence survivors in a way that helps men to interrogate their own underestimation of the degree to which sexual and domestic violence affect their communities and the people they love. Relaying information about the prevalence and impact of violence against women in general terms is likely insufficient to support men in seeing the issue as personally relevant; rather, helping men to form these deeper connections appears critical. Such efforts are reflected in existing men's engagement programs, such as A Call To Men (www.acalltomen.org), a national training organization dedicated to “galvanizing” men's antiviolence participation, and Men Can Stop Rape (www.mencanstoprape.org), which encourages young men to reframe and then act on “strength” in service of ending men's violence against women. Explicitly fostering several of these “meaning shifts” is likely an important element of any male antiviolence building effort.

Limitations

Study limitations should be noted. Perhaps most important, the sample of men in this study almost exclusively identified as White. Findings presented here, therefore, largely reflect White men's antiviolence ally development and the meanings and factors significant to their journey. A glaring gap in both the findings presented here and research about male antiviolence allies more generally is the experiences of men of color around antiviolence mobilization. Future research should examine both the unique factors that might influence the involvement of men of color as well as how racism affects men's relationships to ally movements and to taking a stand around issues of violence. A second limitation is the small, volunteer nature of the sample. Men in this sample self-selected to participate and therefore may represent a subgroup of male antiviolence allies who have particular interests or experiences relative to their work, which may not be more broadly generalizable. Future research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to evaluate the replicability of these findings. Finally, because this study focused only on men who have successfully been engaged in antiviolence work, it is not possible to contrast their stories with those of men who have had sensitizing or opportunity experiences but have not chosen to become involved or with those of men who have disengaged. Additional scholarship focusing on the discriminating factors separating male antiviolence allies from noninvolved men may shed additional light on how to design engagement strategies to maximize effective male participation.

Conclusion

Given that engaging and partnering with men is increasingly recognized as an important component of the formidable challenge of ending violence against women, it is critical to build on our understanding of the processes through which men incorporate antiviolence work into their own lives. This study suggests that, similar to existing models of social justice ally development, exposure to issues of violence, opportunities to critically reflect and make meaning from those exposures, and tangible invitations for involvement are some of the general interrelated factors that motivate men's antiviolence involvement over time. As the practice of engaging men and the models developed to describe it are refined over time, additional work is needed regarding the particular strategies that best foster the kinds of opportunities and meaning making associated with men's commitment to antiviolence efforts. This may be assisted by adapting elements of theoretical frameworks, such as the Transtheoretical Model, with models of ally formation to maximize the efficacy of efforts to broaden the range of men dedicated to ending violence in women's lives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 27 men who volunteered their time to participate in this study, along with the many individuals who provided consultation throughout the process of the research, including Jonathan Grove, Taryn Lindhorst, Kevin Miller, Joshua O'Donnell, and Gayle Stringer.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was supported by a University of Washington, Tacoma Founder's Grant.

Biographies

Erin Casey, PhD, is an assistant professor of social work at the University of Washington, Tacoma. She received her MSW and PhD in social welfare at the University of Washington, Seattle and has more than 10 years of practice experience in the fields of domestic and sexual violence. Her research interests include the etiology of sexual and intimate partner violence perpetration, examining ecological approaches to violence prevention, understanding men's impact on violence prevention efforts, and exploring intersections between violence, masculinities, and sexual risk.

Tyler Smith is a Research Study Coordinator at the University of Washington and Disease Intervention Specialist for Public Health–Seattle King County. He is currently working on a multi-site clinical trial researching the effectiveness of brief intervention counseling during HIV/STD testing in reducing disease acquisition. In addition to his work in public health, other areas of interest include intimate partner violence in same-gender relationships and examining the experiences of LGBTQ youth in the child welfare system.

Footnotes

Authors' Note: Portions of this article were presented at the 2009 Conference on Men and Masculinities in Portland, Oregon and at the 2010 Society for Social Work Research Conference in San Francisco, CA.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Banyard VL, Eckstein RP, Moynihan MM. Sexual violence prevention: The role of stages of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:111–135. doi: 10.1177/0886260508329123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: Evidence from programme interventions. 2007 Retrieved July 29, 2009, from www.who.int/gender/documents/Engaging_men_boys.pdf.

- Berkowitz A. Fostering men's responsibility for preventing sexual assault. In: Schewe PA, editor. Preventing violence in relationships: Interventions across the life span. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 163–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A. Becoming an ally: Breaking the cycle of oppression in people. 2nd. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Fernwood; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Broido EM. The development of social justice allies during college: A phenomeno-logical investigation. Journal of College Student Development. 2000;41:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Starkeya F, Holliday J, Audrey S, Bloorc M, Parry-Langdon, et al. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1595–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60692-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RP. Boys doing good: Young men and gender equity. Educational Review. 2003;55:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks CV, Goodall GR, Hughes R, Jaffe PG, Baker LL. Engaging men and boys in preventing violence against women: Applying a cognitive-behavioral model. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:217–239. doi: 10.1177/1077801206297336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy WS, Schwartz MD, Alvi S. The role of profeminist men in dealing with woman abuse on the Canadian college campus. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:918–935. [Google Scholar]

- Earle JP. Acquaintance rape workshops: Their effectiveness in changing the attitudes of first-year college men. NASPA Journal. 1996;34:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano PM, Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD, Linkenbach J, Stark C. Engaging men as social justice allies in ending violence against women: Evidence for a social norms approach. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52:105–112. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MI, Bowen GS, Gay CL, Mattson TR, Bital E, Kelly JA. HIV, sex and social change: Applying ESID principles to HIV prevention research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32:333–344. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004752.42987.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood M. Changing men: Best practice in sexual violence education. Women Against Violence. 2005;18:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Funk R. Reaching men: Strategies for preventing sexist attitudes, behaviors, and violence. Indianapolis, IN: JIST; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Funk R. Men's work: Men's voices and actions against sexism and violence. Journal of Intervention and Prevention in the Community. 2008;36:155–171. doi: 10.1080/10852350802022456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foubert JD, Newberry JT, Tatum JL. Behavior differences seven months later: Effects of a rape prevention program on first-year men who join fraternities. NASPA Journal. 2007;44:728–749. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SR. Evaluation findings: Men Can Stop Rape, Men of Strength Clubs 2004-2005. 2005 Retrieved August 8, 2007, from www.mencanstoprape.org.

- Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE. Toward a model of White racial identity development. In: Helms JE, editor. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research and practice. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1990. pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J. Reconstructing masculinity in the locker room: The Mentors in Violence Prevention Project. Harvard Educational Review. 1995;65:163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Wright C, Kaluzny G. If “boys will be boys,” then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles. 2002;46:359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Reason RD, Miller EAR, Scales TC. Toward a model of racial justice ally development. Journal of College Student Behavior. 2005;46:530–546. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff NJ, Dupont I. Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class and gender. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:38–64. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JL. Peer educators and close friends as predictors of male college students' willingness to prevent rape. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48:75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum B. Teaching White students about racism: The search for White allies and the restoration of hope. Teachers College Record. 1994;95:462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, incidence and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control; 1998. [Google Scholar]