Abstract

Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, or X-linked Dominant Chondrodysplasia Punctata Type 2 (CDPX2), is a genodermatosis caused by mutations in EBP. While typically lethal in males, females with CDPX2 generally manifest by infancy or childhood with variable features including congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, chondrodysplasia punctata, asymmetric shortening of the long bones, and cataracts. We present a 36-year-old female with short stature, rhizomelic and asymmetric limb shortening, severe scoliosis, a sectorial cataract, and no family history of CDPX2. Whole exome sequencing (WES) revealed a p.Arg63del mutation in EBP, and biochemical studies confirmed a diagnosis of CDPX2. Short stature in combination with ichthyosis or alopecia, cataracts, and limb shortening in an adult should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of CDPX2. As is the case with many genetic syndromes, the hallmark features of CDPX2 in pediatric patients are not readily identifiable in adults. This case demonstrates the utility of WES as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of adults with genetic disorders.

Introduction

Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome (OMIM 302960), or X-linked Dominant Chondrodysplasia Punctata Type 2 (CDPX2), is a genodermatosis that combines chondrodysplasia punctata with ocular and skin manifestations1. CDPX2 is caused by mutations in the EBP gene that encodes emopamil binding protein [Braverman et al., 1999; Derry et al., 1999] or 3-β-hydroxysteroid-Δ8,Δ7-isomerase, an enzyme involved in cholesterol biosynthesis. Accumulation of 8(9)-cholestenol and 8-dehydrocholesterol in plasma or skin samples is diagnostic of this condition [Braverman et al., 1999; Derry et al., 1999; Kelley et al., 1999].

CDPX2 is often lethal in males. Affected females typically present by early childhood with characteristic craniofacial features, asymmetric shortening of long bones with epiphyseal stippling, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma that follows the lines of Blaschko, and cataracts that are often unilateral or sectorial [Cañueto et al., 2012; Happle, 1979; Has et al., 2000; Has et al., 2002; Herman et al., 2002; Ikegawa et al., 2000]. Facial features include frontal bossing, flattening of the nasal bridge, and asymmetry of the face [Cañueto et al., 2012]. The characteristic congenital ichthyotic skin lesions regress over time and are replaced by atrophoderma in a similar distribution that follows lines of Blaschko [Cañueto et al., 2014]. While many females are diagnosed in early childhood, resolution of both ichthyosis and punctate calcifications makes ascertainment of CDPX2 in adults without a positive family history more challenging. For this reason, the diagnosis of CDPX2 in an adult is often made after diagnosis of an affected fetus or child [Umranikar et al., 2006].

In the present report, we describe a 36-year-old female with short stature, scoliosis, and visual impairment and a non-contributory family history who was diagnosed with CDPX2 by whole exome sequencing (WES).

Case Report

The proband, a 36-year-old female, was referred to the Adult Genetics Clinic for evaluation of short stature. She was the product of a non-consanguineous union between individuals of African American ethnicity, and there was no family history of short stature. Although pediatric records were not available, she reported a normal birth length but childhood height measurements below the expected height-for-age. During childhood, she had multiple surgical interventions including spinal surgery for scoliosis, and an unknown orthopedic procedure on her left leg. There was no history of fractures, joint dislocations, teeth abnormalities, or bone pain.

Additional medical history included asymmetric hearing loss attributed to structural abnormalities within the auditory canal and surgery for protruding ears in childhood. An absent nasal septum required a bone graft, and she had surgical reconstruction of the nose after a motor vehicle accident. Obstructive sleep apnea, thought to be secondary to obesity, led to nocturnal hypoxemia that was managed with continuous positive airway pressure. She had a learning disability and required special education classes. Despite multiple attempts, the proband was unable to conceive.

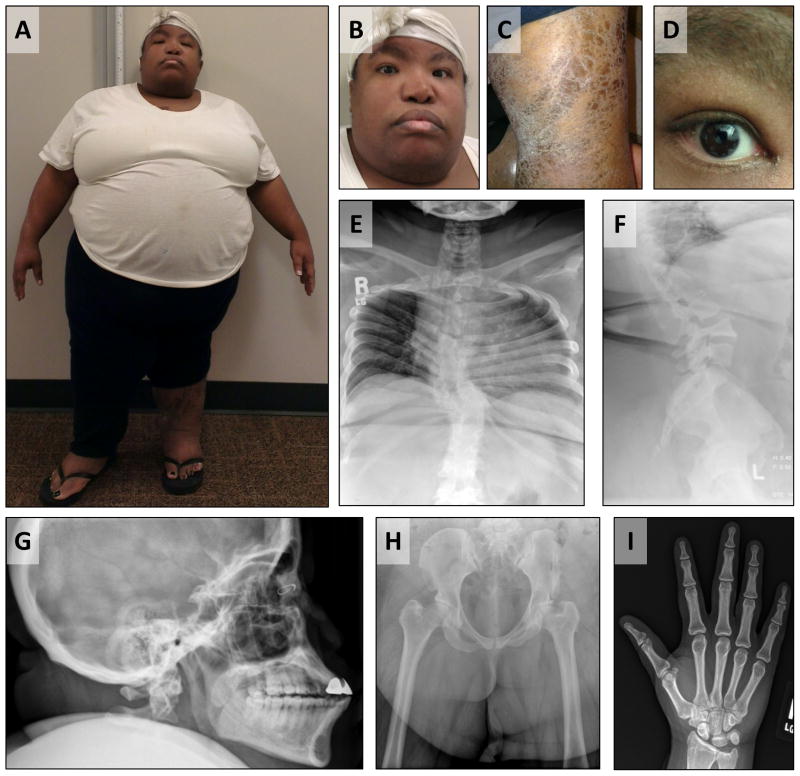

Physical examination revealed a height of 119.4 cm (> 6 standard deviations below mean for age and race), a weight of 114.3 kg (85th – 90th centile), with a fronto-occipital head circumference of 55.5 cm [McDowell et al., 2008]. The upper:lower segment ratio was 1.095. Skeletal examination revealed rhizomelic shortening, tapered fingers, brachydactyly of the feet, and leg length discrepancy (Figure 1A). Facial exam was notable for hypertelorism with upslanting palpebral fissures, midface hypoplasia, and facial asymmetry (Figure 1B). The oropharynx was small with absent uvula and tonsils. Skin exam revealed atrophic skin involving bilateral lower extremities, with regions of dystrophy characterized by dry, thickened epidermis and scaling (Figure 1C). There was no scarring alopecia, but atrophic nails and non-pitting lower extremity edema were present. Subsequent evaluation revealed a sectorial cataract of the right eye (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Clinical phenotype of the patient.

A. Asymmetric, rhizomelic limb shortening. B. Hypertelorism, upslanting palpebral fissures, midface hypoplasia. C. Ichthyosis of lower legs. D. Sectorial cataract of right eye. E. Frontal thoracic and lumbar spine radiograph, scoliosis. F. Lateral lumbar spine radiograph, posterior wedging of L4 vertebral body, presumed congenital. G. Lateral skull radiograph, midface hypoplasia. H. Frontal view of pelvis, shortening of femoral necks and greater trochanteric overgrowth (relatively large and cranially displaced greater trochanters). I. Frontal view of right hand, mild negative ulnar variance, no evidence of epiphyseal stippling.

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed normal serum calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels. Sequencing of COL2A1 did not reveal any mutations. A skeletal survey did not reveal epiphyseal stippling but did demonstrate other features previously reported in CDPX2, including scoliosis and congenital vertebral anomalies (Figure 1E-I). Radiographs further demonstrated several nonspecific findings such as shortening of the femoral necks, greater trochanter overgrowth, and negative ulnar variance. A 180K oligonucleotide chromosome microarray analysis did not reveal any copy-number variants (CNVs). With these findings, common causes of short stature such as Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy, a type II collagenopathy, and pathologic CNVs were considered unlikely. WES was performed to elucidate the diagnosis.

Methods

Clinical Study

The study subject was enrolled in a research protocol that was approved by Baylor College of Medicine's Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was obtained specifically for WES and the publication of medical information and photography.

WES

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood monocytes using standard techniques. WES was performed using capture reagents developed at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center (BCM-HGSC) and made available by Nimblegen (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/seqcap/ez/designs/index.html). Sequencing was conducted on Illumina HiSeq2000 with alignment, filtering, and analysis performed as described previously [Campeau et al., 2012].

Sanger sequencing

Polymerase chain reaction primers (5′- TTCGGTCCATTTACATTTCTCA-3′ and 5′-AAATCCCATCCCACAGCATA-3′) were designed to amplify exon 2 of EBP to include the mutation (NM_006579.2:c.186_188del) identified by WES. PCR products were generated with TaqMan polymerase (ABI, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using 1 ng/μl of genomic DNA according to the manufacturer's protocol and sequenced by chain-termination (Sanger) sequencing using the same primers at Beckman Coulter Genomics (Danvers, MA).

Sterol analysis

Sterol analysis was performed in plasma using ion-ratio GC/MS on an Agilent 6390N/5973 GC/MS system as previously described [Kelley, 1995] with modifications to the GC/MS method to include ions specific for 8(9)-cholestenol (m/z = 458) and 8-dehydrocholesterol (m/z = 351). Sterol analysis in skin flakes was performed in a similar manner, but with prior hydrolysis of 2 – 5 mg of flakes in 8N KOH and methanol (1:1) at 65 °C for 30 minutes.

Results

WES identified a previously described c.186_188delGGC (p.Arg63del) mutation in EBP that was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Figure 1) [Derry et al., 1999]. DNA from the proband's parents was not available for testing. Plasma sterol analysis demonstrated an 8(9)-cholestenol level of 2.64 μg/ml (normal range 0-0.23 μg/ml), and an analysis of skin flakes from an affected area demonstrated an 8(9)-cholestenol level that was 26.9% of total sterols (control 0.2%). These biochemical results confirmed a diagnosis of CDPX2.

Discussion

Our patient presented with some features typical for CDPX2 such as short stature, rhizomelia, scoliosis, sectorial cataract, atrophic skin, and facial asymmetry; however, features that are not typical of the condition including mild cognitive impairment and marked obesity were also present. There was a family history of learning disability in one male child of a paternal cousin, but no family history of short stature or other skeletal abnormalities. Medical records from childhood were unavailable, and formal IQ testing had not been performed. As the diagnosis was not obvious at the time of evaluation, WES was performed and revealed a diagnosis of CDPX2. Despite being delayed until adulthood, her diagnosis allows for genetic and reproductive counseling regarding the recurrence risk for this disorder.

We compared the phenotype in our patient with that of other adult patients who had been diagnosed with CDPX2 without a family history or an offspring with the disorder (Table I) [Has et al., 2000; Has et al., 2002; Tysoe et al., 2008; Whittock et al., 2003a; Whittock et al., 2003b]. The most common presenting features in such patients were dermatologic abnormalities (10/11 patients) ranging from ichthyosis and hyperkeratosis to follicular atrophoderma. Alopecia was reported in 9 of the 11 patients. Visual impairment or cataracts were observed in 8/11 patients. Asymmetric limb shortening was the most common skeletal finding (8/11 patients). Thus, these data suggest that even in the absence of a family history of the disorder, the combination of skin abnormalities, particularly in the setting of patchy or cicatricial alopecia, cataracts, and asymmetric limb shortening, should suggest a diagnosis of CDPX2.

Table I.

CDPX2 patients ascertained as adults, in the absence of a positive family history or affected offspring.

| Reference | Age (y) | Stature | Skin | Eye | Bone | Intellect | Molecular Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has, 2000 | 33 | 155 cm | Ichthyosis, Alopecia, Hyperpigmentation, Atrophoderma | Cataract | Asym. shortening, Kyphoscoliosis, Facial asymmetry | N.P.2 | c.390delA; p.Pro131Hisfs*7 |

| Has, 2002 | 21 | N.P. | Hyperkeratosis, Alopecia | Vis. Imp. | Asym. shortening | N.P. | c.608T>C; p.Leu203Pro |

| Has, 2002 | 37 | N.P. | Hyperkeratosis, Alopecia | Vis. Imp. | Severe orthopedic handicap | N.P. | c.451C>T; p.Gln151Ter |

| Has, 2002 | 43 | N.P. | Alopecia | No impairment | Vertebral changes, Hip dislocation | N.P. | c.141G>A; p.Trp47Ter |

| Has, 2002 | 38 | N.P. | Ichthyosis, Alopecia | Vis. Imp. | Asym. shortening | N.P. | c.338+1-G>A; splice site |

| Whittock, 2003a | 26 | Short | Ichthyosis, Alopecia, Hyperkeratosis, Sparse dry hair | Cataract | Asym. shortening | Normal | c.484G>C; p.Asp162His |

| Whittock, 2003a | 25 | N.P. | Ichthyosis, Alopecia, Hyperkeratosis, Sparse dry hair | Cataracts | Asym. shortening, Scoliosis | Normal | c.187C>T; p.Arg63Ter |

| Whittock, 2003a | 38 | Short | Ichthyosis, Alopecia, Hyperkeratosis, Sparse dry hair, Nail dystrophy | Cataract Unilateral optic nerve hypoplasia | Asym. shortening, 2/3 toe syndactyly | Normal | c.204G>A; p.Trp68Ter |

| Whittock, 2003b | 30 | Normal 159 cm | Ichthyosis, Alopecia, Atrophoderma, Hyperkeratosis, Coarse sparse hair, Nail dysplasia | Normal | Clinodactyly | Normal | c.399C>A; p.Ser133Arg |

| Tysoe, 2008 | 24 | N.P. | Ichthyosis, Atrophoderma, Coarse hair, Nail dystrophy | N.P. | Asym. shortening, Scoliosis | N.P. | c.293C>T; p.Ser98Phe |

| Present report | 36 | Short, 119 cm | Ichthyosis, Atrophoderma | Cataract | Asym. shortening, Scoliosis, Facial asymmetry, Nasal complications, Absent uvula, Hearing loss | “Slow learner” | c.186_188delGGC p.Arg63del |

Abbreviations: Asym – asymmetric; N.P. – Not provided; Vis. Imp. – Visual Impairment.

CDPX2 is caused by mutations in the gene encoding 3-β-hydroxysteroid-Δ8,Δ7-isomerase, an enzyme involved in the distal cholesterol biosynthesis pathway [Braverman et al., 1999; Derry et al., 1999]. Cholesterol is important for the barrier function of the skin and the membrane of the lens, and also plays an important role in the regulation of hedgehog signaling that is necessary during development [Cañueto et al., 2014; Jira, 2013; Kanungo et al., 2013]. Accumulation of toxic intermediates may further abrogate hedgehog signaling and has been proposed to contribute to the cutaneous and skeletal phenotypes [Cañueto et al., 2014].

The diagnosis of CDPX2 in adults is made difficult by the fact that some of the characteristic features such as epiphyseal stippling and erythroderma typically are not observed in adulthood [Happle, 1979; Paul, 1954; Selakovich and White, 1955; Theander and Pettersson, 1978]. Moreover, the marked variability of phenotype [Traupe et al., 1992] due to skewed X-inactivation and somatic mosaicism makes recognition of adults with this condition challenging, and females are often diagnosed only due to having an affected offspring [Has et al., 2000; Morice-Picard et al., 2011; Shirahama et al., 2003]. Although the proportion of CDPX2 cases that are truly de novo is not well-known, one recent study reporting molecular analysis of 9 probands and their parents reported 3 inherited EBP mutations [Cañueto et al., 2012]. Somatic mosaicism may result in an underappreciation of inherited cases [Has et al., 2000; Morice-Picard et al., 2011].

In summary, a diagnosis of CDPX2 should be considered in adult patients with dermatologic abnormalities such as ichthyosis, alopecia, cataracts, and asymmetric limb shortening. Even in the setting of a mild phenotype, CDPX2 should be recognized and diagnosed so that appropriate reproductive counseling and medical surveillance, including regular ophthalmologic and orthopedic evaluation, can be provided. Lastly, this case underscores the importance of WES in the adult genetics clinic as the evolution of phenotypes in disorders that are typically diagnosed in childhood creates diagnostic challenges in adult patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Sequencing data. A. Exome sequencing data demonstrates a heterozygous deletion of three consecutive nucleotides in EBP, resulting in an in-frame deletion. B. Sanger sequencing confirms the in-frame deletion.

Acknowledgments

J.E.P. and L.C.B. were supported by the Medical Genetics Research Fellowship Program NIH/NIGMS NIH T32 GM07526. L.C.B. was supported by the Genzyme/ACMG Foundation for Genetic and Genomic Medicine Medical Genetics Training Award in Clinical Biochemical Genetics. S.C.S.N. is supported by the Clinical Scientist Development Award by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. This work was supported by the Baylor College of Medicine Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (HD024064) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and NICHD P01 HD070394 (B.H.L.). We thank Alyssa Tran for patient enrollment and Yuqing Chen for technical assistance. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Key words – Chondrodysplasia Punctata, Cataract, Ichthyosis, EBP

References

- Braverman N, Lin P, Moebius FF, Obie C, Moser A, Glossmann H, Wilcox WR, Rimoin DL, Smith M, Kratz L, Kelley RI, Valle D. Mutations in the gene encoding 3 beta-hydroxysteroid-delta 8, delta 7-isomerase cause X-linked dominant Conradi-Hünermann syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999;22(3):291–294. doi: 10.1038/10357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau PM, Lu JT, Sule G, Jiang MM, Bae Y, Madan S, Högler W, Shaw NJ, Mumm S, Gibbs RA, Whyte MP, Lee BH. Whole-exome sequencing identifies mutations in the nucleoside transporter gene SLC29A3 in dysosteosclerosis, a form of osteopetrosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(22):4904–4909. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañueto J, Girós M, Ciria S, Pi-Castán G, Artigas M, García-Dorado J, García-Patos V, Virós A, Vendrell T, Torrelo A, Hernández-Martín A, Martín-Hernández E, Garcia-Silva MT, Fernández-Burriel M, Rosell J, Tejedor M, Martínez F, Valero J, García JL, Sánchez-Tapia EM, Unamuno P, González-Sarmiento R. Clinical, molecular and biochemical characterization of nine Spanish families with Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome: new insights into X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata with a comprehensive review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(4):830–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañueto J, Girós M, González-Sarmiento R. The role of the abnormalities in the distal pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis in the Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841(3):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry JM, Gormally E, Means GD, Zhao W, Meindl A, Kelley RI, Boyd Y, Herman GE. Mutations in a delta 8-delta 7 sterol isomerase in the tattered mouse and X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Nat Genet. 1999;22(3):286–290. doi: 10.1038/10350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happle R. X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Review of literature and report of a case. Hum Genet. 1979;53(1):65–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00289453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Müller D, Floeth M, Folkers E, Donnai D, Traupe H. The Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome (CDPX2) and emopamil binding protein: novel mutations, and somatic and gonadal mosaicism. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(13):1951–1955. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Seedorf U, Kannenberg F, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Folkers E, Fölster-Holst R, Baric I, Traupe H. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and molecular genetic studies in families with the Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118(5):851–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman GE, Kelley RI, Pureza V, Smith D, Kopacz K, Pitt J, Sutphen R, Sheffield LJ, Metzenberg AB. Characterization of mutations in 22 females with X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata (Happle syndrome) Genet Med. 2002;4(6):434–438. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegawa S, Ohashi H, Ogata T, Honda A, Tsukahara M, Kubo T, Kimizuka M, Shimode M, Hasegawa T, Nishimura G, Nakamura Y. Novel and recurrent EBP mutations in X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Am J Med Genet. 2000;94(4):300–305. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001002)94:4<300::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jira P. Cholesterol metabolism deficiency. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;113:1845–1850. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00054-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo S, Soares N, He M, Steiner RD. Sterol metabolism disorders and neurodevelopment-an update. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2013;17(3):197–210. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley RI. Diagnosis of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry of 7-dehydrocholesterol in plasma, amniotic fluid and cultured skin fibroblasts. Clin Chim Acta. 1995;236(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley RI, Wilcox WG, Smith M, Kratz LE, Moser A, Rimoin DS. Abnormal sterol metabolism in patients with Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome and sporadic lethal chondrodysplasia punctata. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83(3):213–219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990319)83:3<213::aid-ajmg15>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell MA, Fryar CD, Ogden Cl, Flegal KM. Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2003-2006. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice-Picard F, Kostrzewa E, Wolf C, Benlian P, Taïeb A, Lacombe D. Evidence of postzygotic mosaicism in a transmitted form of Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome associated with a novel EBP mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(9):1073–1076. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul LW. Punctate epiphyseal dysplasia (chondrodystrophia calcificans congenita); report of case with nine year period of observation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1954;71(6):941–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selakovich WG, White JW. Chondrodystrophia calcificans congenita; report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37-A(6):1271–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahama S, Miyahara A, Kitoh H, Honda A, Kawase A, Yamada K, Mabuchi A, Kura H, Yokoyama Y, Tsutsumi M, Ikeda T, Tanaka N, Nishimura G, Ohashi H, Ikegawa S. Skewed X-chromosome inactivation causes intra-familial phenotypic variation of an EBP mutation in a family with X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Hum Genet. 2003;112(1):78–83. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0844-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theander G, Pettersson H. Calcification in chondrodysplasia punctata. Relation to ossification and skeletal growth. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1978;19(1B):205–222. doi: 10.1177/028418517801901b07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traupe H, Müller D, Atherton D, Kalter DC, Cremers FP, van Oost BA, Ropers HH. Exclusion mapping of the X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata/ichthyosis/cataract/short stature (Happle) syndrome: possible involvement of an unstable pre-mutation. Hum Genet. 1992;89(6):659–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00221958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tysoe C, Law CJ, Caswell R, Clayton P, Ellard S. Prenatal testing for a novel EBP missense mutation causing X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28(5):384–388. doi: 10.1002/pd.1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umranikar S, Glanc P, Unger S, Keating S, Fong K, Trevors CD, Myles-Reid D, Chitayat D. X-Linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata: prenatal diagnosis and autopsy findings. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(13):1235–1240. doi: 10.1002/pd.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittock NV, Izatt L, Mann A, Homfray T, Bennett C, Mansour S, Hurst J, Fryer A, Saggar AK, Barwell JG, Ellard S, Clayton PT. Novel mutations in X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata (CDPX2) J Invest Dermatol. 2003a;121(4):939–942. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittock NV, Izatt L, Simpson-Dent SL, Becker K, Wakelin SH. Molecular prenatal diagnosis in a case of an X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata. Prenat Diagn. 2003b;23(9):701–704. doi: 10.1002/pd.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Sequencing data. A. Exome sequencing data demonstrates a heterozygous deletion of three consecutive nucleotides in EBP, resulting in an in-frame deletion. B. Sanger sequencing confirms the in-frame deletion.