Abstract

Purpose

Although strategies exist for improving cardiac rehabilitation (CR) participation rates, it is unclear how frequently these strategies are utilized and what efforts are being made by CR programs to improve participation rates.

Methods

We surveyed all CR program directors in the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation’s database. We assessed program characteristics, use of specific referral and recruitment strategies, and self-reported program participation rates.

Results

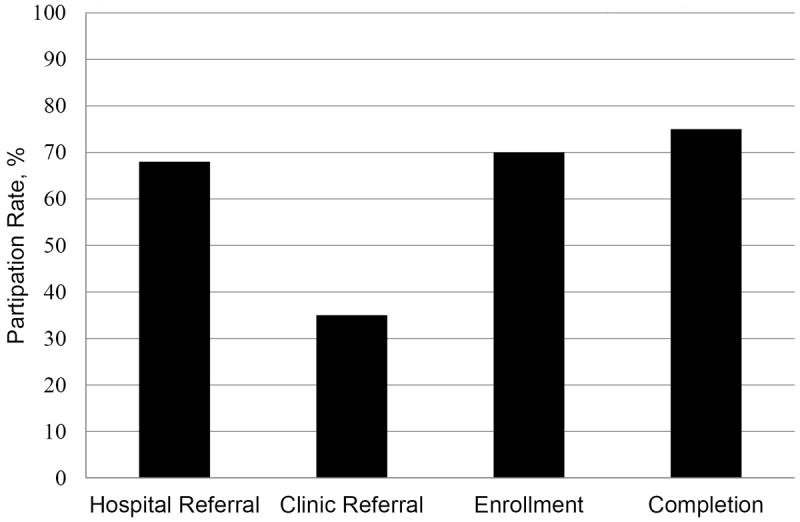

Between 2007 and 2012, 49% of programs measured hospital referral, 21% measured office/clinic referral, 71% measured program enrollment, and 74% measured program completion rates. Program-reported participation rates [interquartile range] were 68 [32 to 90]% for hospital referral, 35 [15 to 60]% for office/clinic referral, 70 [46 to 80]% for enrollment, and 75 [62 to 82]% for completion. The majority of programs utilize a hospital-based systematic referral, liaison facilitated referral, or inpatient CR program (64%, 68%, and 60% of the time, respectively). Early appointments (< 2 weeks) were utilized by 35% and consistent phone call appointment reminders were utilized by 50% of programs. Quality improvement (QI) projects were performed by about half of CR programs. Measurement of participation rates was highly correlated with performing QI projects (p < 0.0001.)

Conclusions

Although programs are aware of participation rate gaps, the monitoring of participation rates is suboptimal, quality improvement initiatives are infrequent, and proven strategies for increasing patient participation are inconsistently utilized. These issues likely contribute to the national CR participation gap and may prove to be useful targets for national QI initiatives.

Keywords: Cardiac Rehabilitation, Quality Improvement, Participation, Referral

Introduction

Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) reduces mortality rates for patients with cardiac disease and referral to CR is given the strongest level of recommendation by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology in practice guidelines.1, 2 In addition, CR is has also been endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a performance measure.3 Despite this, CR is highly under-utilized with as few at 20-30% of patients participating nationally.4, 5 Although there are many reasons why patients do not participate,6 multiple studies demonstrate that providers and hospital systems play a key role7 in encouraging patient participation with some programs reporting participation rates >70%.8 Consequently, the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR) have called upon hospitals, providers, CR programs, and CR program Medical Directors to improve patient participation.9-11

Several key strategies have been previously described for increasing patient participation. These include strong physician recommendations for participation;12 an early appointment to CR;13 a reminder phone call in the 2-3 days prior to the enrollment appointment;14 use of a hospital-based liaison who provides program information, encouragement, and otherwise facilitates outpatient referral;15 and an automatic/systematic referral which does not rely on physician initiative or memory.15 Each of these key techniques improves participation significantly and if uniformly applied across the United State would significantly improve CR participation rates and reduce the burden of heart disease and numbers of recurrent events.

Although these techniques have been demonstrated to increase patient participation, it is unclear how broadly these strategies are applied across the United States. In addition, it is unknown how often participation rates are being monitored, how often quality improvement projects are being carried out by CR programs, and what impact those quality improvement projects are having on patient outcomes.

To address these gaps in knowledge and to help identify methods for improving CR participation, we assessed the characteristics of a national sample of CR programs in the US with a particular focus on the use of evidence-based strategies to improve CR referral and enrollment. We hypothesized that the majority of programs do not monitor participation and completion rates, utilize evidence-based quality CR participation strategies, or regularly perform quality improvement initiatives.

Methods

In November 2012, we conducted a national survey of program directors registered in the AACVPR national database. We excluded programs with only pulmonary rehabilitation, only inpatient CR services, or programs located outside the United States. Surveys were administered by the AACVPR, were anonymous, voluntary, and responses were collected through the use of the online survey website, www.surveymonkey.com. Program directors were given one survey reminder 2 weeks after the original survey distribution. Participants were entered into an incentive drawing among which 15 participants won a heart health related book worth approximately $20.

All questions were developed by the primary author (QP) and reviewed for content, clarity, and face validity by all other authors. The full survey is found in the appendix. There were 30 survey questions which assessed program size, characteristics, programming, and location relative to referring hospitals and clinics (questions 3-9.) We also assessed measured and estimated program participation rates as well as referral, enrollment, and retention strategies (questions 11-14 and 20-29.) We previously published part of the survey which assessed response bias, program capacity, and growth potential (questions 13-19.) In this article, we report our findings regarding the utilization of specific patient recruitment strategies in both hospital and outpatient clinic settings. Details regarding our survey response rate and response-bias analysis have been previously described.16 The survey was reviewed and approved by AACVPR leadership and the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Measures

Our primary outcome was the measurement of participation rates at least once in the past 5 years (question 26.) Any respondent who answered this question was considered to have completed the survey for the purpose of calculating the survey response rate because measurement of a participation rate is a key first step in quality improvement. Although we also assessed program-reported participation rates, we felt these data would be less reliable, susceptible to social desirability bias, and as such were exploratory outcomes. To speed survey response, we employed skip logic when possible. We required participants to answer basic identifying questions, skip-logic questions, and our primary outcome (questions 1, 2, 18, 23, and 26.) All other questions were voluntary and could be skipped or answered incompletely.

Several important terms required definition. Specific wording used in the survey can be found in the online appendix. A liaison-facilitated referral was defined to occur when a specific staff member discusses outpatient CR, encourages attendance, and facilitates referral for all eligible patients. An automatic referral was defined to occur as part of an order set that does not depend on physician initiative or memory. Referral rate was defined as the percentage of eligible patients in a hospital or clinic who were referred to cardiac rehabilitation. Enrollment rate was defined as the percentage of referred patients who attended >1 exercise session of CR. Completion rate was defined as the percentage of enrolled patients who completed the program, as defined by each individual program. Cumulatively, these four rates (hospital referral, clinic referral, enrollment, and completion) were collectively referred to as “participation rates” when speaking about the combined group.

Analysis

All data were entered into a database. Except when reported separately, we collapsed all negative, unknown, or uncertain answers into one “null” category. Descriptive statistics were applied. Categorical data are reported as a percent of respondents and continuous data with mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range as appropriate for normally distributed or skewed data, respectively. We tested continuous data associations with Spearman’s correlation coefficient and categorical associations with Chi-squared. All analyses were performed with JMP 9.0.1 (SAS institute, Cary, NC.)

We estimated the percentage of 100 hypothetical eligible patients who complete CR using reported participation rates by combining referral, enrollment and completion rates. We utilized the percentage of patient referred from the hospital (vs. clinic) to estimate the starting ratio of patients referred from the clinic or the hospital. To test for the potential impact of QI initiatives on patient participation rates, we also stratified programs according to the presence of QI initiatives and compared rates using a t-test.

Results

Out of 812 program directors, 334 (41%) answered at least one question, and 290 (36%) completed the full survey. The number of respondents on each question is shown in table columns labeled N, and varied from question to question due to incomplete responses, survey drop out, and the use of skip logic to speed survey response by skipping unrelated questions. We demonstrated previously in a non-response bias analysis that survey respondents were generally representative of AACVPR programs found in the database.16

Program characteristics and enrollment strategies are found in Table 1. Findings included that most patient started CR between 3-4 weeks after discharge, and that 50% of programs routinely provided telephone reminders of upcoming enrollment appointments.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Cardiac Rehabilitation Program Features and Enrollment Strategies

| N | Category | Prevalence, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Structural | |||

|

| |||

| Local population | 335 | <50,000 | 37 |

| 50,000 – 99,999 | 20 | ||

| 100,000 – 249,999 | 20 | ||

| 250,000 – 500,999 | 10 | ||

| 500,000 – 999,999 | 7 | ||

| ≥1,000,000 | 6 | ||

|

| |||

| Inpatient vs. outpatient referral, % | 338 | 0-20 | 24 |

| 21-40 | 8 | ||

| 41-60 | 9 | ||

| 61-80 | 18 | ||

| 81-100 | 41 | ||

|

| |||

| Location relative to hospital | 340 | Same building | 44 |

| Same campus | 20 | ||

| 5-10 minutes | 8 | ||

| >10 minutes | 28 | ||

|

| |||

| Location relative to clinic | 339 | Same building | 34 |

| Same campus | 27 | ||

| 5-10 minutes | 21 | ||

| >10 minutes | 18 | ||

|

| |||

| Member of CR network | 340 | 26 | |

|

| |||

| Member of AACVPR | 340 | 96 | |

|

| |||

| Electronic medical record | 340 | 56 | |

|

| |||

| Academic medical center | 340 | 19 | |

|

| |||

| Ongoing CR research | 340 | 7 | |

|

| |||

| Enrollment Strategies | |||

|

| |||

| Time interval from hospital discharge to enrollment | 328 | 1-2 weeks | 35 |

| 3-4 weeks | 49 | ||

| 5-6 weeks | 15 | ||

| 7-8 weeks | 12 | ||

| ≥9 weeks | 3 | ||

|

| |||

| Percentage of time a telephone reminder is made in the 2-3 days prior to initial appointment, % | 326 | 0-20 | 36 |

| 21-40 | 5 | ||

| 41-60 | 5 | ||

| 61-80 | 4 | ||

| 81-100 | 50 | ||

|

| |||

| Programmatic features | |||

|

| |||

| Gender-tailored sessions | 334 | --- | 2 |

|

| |||

| Age-tailored sessions | 334 | --- | 7 |

|

| |||

| Behavioral contracts | 334 | --- | 23 |

|

| |||

| Spouse participation | 334 | --- | 73 |

|

| |||

| Incentive programs | 334 | --- | 33 |

|

| |||

| Evening hours | 314 | --- | 16 |

|

| |||

| Days open per week, mean ± SD | 314 | --- | 3.6 ± 0.9 |

Abbreviations: AACVRP, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; CR, cardiac rehabilitation.

Of 314 program directors, 281 (89%) reported having “specific knowledge” of their primary hospital’s referral process and 75% (234/311) reported having specific knowledge of their primary clinic’s referral process. Conversely, only 7.2% (21/289), 14.4% (41/285), 0.7% (2/290), and 0.3% (1/290) of program directors reported being unable to measure hospital referral, office/clinic referral, enrollment, and completion rates, respectively.

Specific referral strategies and referral materials are found in Table 2 for both clinic and hospital settings as reported by program directors with a “specific knowledge” of referral techniques. Utilization of inpatient systematic referrals, liaison-facilitated referrals, and a Phase I CR program were each reported by about 2/3rds of programs. However, only 29% (67/231) used all three of these techniques and 4.7% (11/231) reported using no inpatient referral techniques.

Table 2.

Hospital and Clinic Referral Strategies and Materials.

| N | Prevalence, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital | ||

| Referral strategies | ||

| Phase I program | 340 | 60 |

| Systematic referral | 279 | 63 |

| Liaison | 277 | 68 |

| Number of referral strategies utilized | ||

| 0 | 231 | 5 |

| 1 | 231 | 22 |

| 2 | 231 | 44 |

| 3 | 231 | 29 |

| Timing/trigger for systematic referral | ||

| Admission | 206 | 14 |

| Discharge | 206 | 58 |

| Surgery | 206 | 42 |

| Cardiac catheterization | 206 | 52 |

| Other (stress test/blood test/biomarker) | 206 | 23 |

| Referral materials | ||

| Appointment day/time | 279 | 26 |

| Map/directions | 279 | 32 |

| Flyer/handout | 279 | 73 |

| Contact information | 279 | 82 |

| Clinic | ||

| Systematic referral | 234 | 18 |

| Referral materials | ||

| Appointment day/time | 230 | 20 |

| Map/directions | 230 | 18 |

| Flyer/handout | 230 | 18 |

| Contact information | 230 | 70 |

Table 3 shows the frequency of CR participation rate monitoring. We observed a strong association between the measurement of participation rates and quality improvement projects (p< 0.001 for all.)

Table 3.

Program-Reported CR Participation Rate Monitoring and QI Projects

| N | Measured in past 5 years | QI project in past 5 years | χ2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital referral | 289 | 49% | 62% | 74.5 | <.0001 |

| Office/clinic referral | 285 | 21% | 42% | 45.9 | <.0001 |

| Program enrollment | 290 | 71% | 60% | 33.3 | <.0001 |

| Program completion | 290 | 74% | 57% | 48.2 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: CR, cardiac rehabilitation; QI, quality improvement.

Note: Rates were determined per Figure 1 and as described in the text.

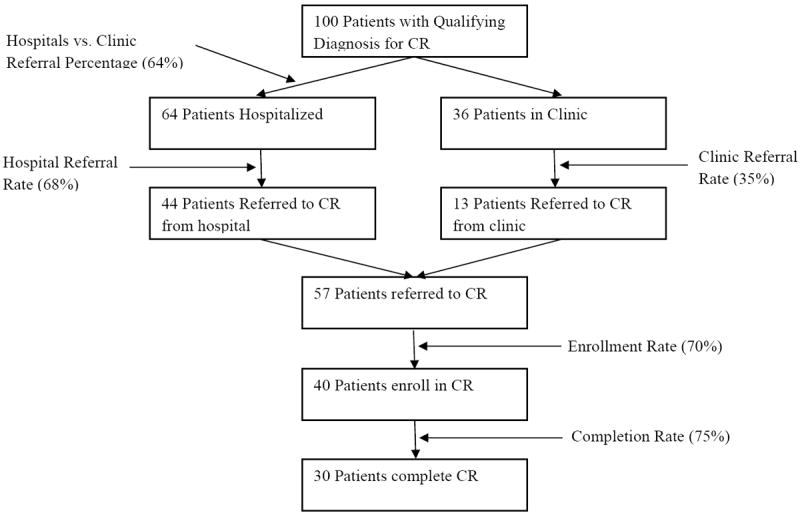

Table 4 demonstrates program-reported CR program participation rates and Figure 1 highlights these findings. Although few programs reported measured rates for the year 2012, measured vs. estimated rates did not differ significantly between programs except for a 12% higher hospital referral rate among programs reporting measured rates (p = 0.02). Figure 2 demonstrates that only 30 patients out of a hypothetical 100 eligible patients succeed in moving from eligibility all the way to CR completion using current systems of referral, recruitment, and retention in the United States.

Table 4.

Program-Reported Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation Rates

| Participation Rate | N | Overall participation rate % (IQR) | % of respondents reporting measured participation rates | Measured participation rate % (IQR) | Estimated participation rate % (IQR) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Referral | 248 | 68% (32 to 90) | 26% | 77.5% (40 to 98) | 65% (33 to 85) | 0.02 |

| Office/Clinic Referral | 235 | 35% (15 to 60) | 8% | 35% (19 to 73) | 34% (15 to 60) | 0.46 |

| Program Enrollment | 251 | 70% (46 to 80) | 40% | 67.5% (45 to 80) | 70% (47 to 80) | 0.49 |

| Program Completion | 252 | 75% (62 to 82) | 45% | 75.5% (67 to 85) | 75% (60 to 80) | 0.10 |

IQR = inter quartile range, N = number of survey respondents

Rates are defined as per Figure 1 and the manuscript text

Figure 1.

National Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation Rates As Reported by Directors of AACVPR Registered Programs

AACVPR = American Association for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Referral rate was defined as the percentage of eligible patients in a hospital or clinic who were referred to cardiac rehabilitation. Enrollment rate was defined as the percentage of referred patients who attended >1 exercise session of CR. Completion rate was defined as the percentage of enrolled patients who completed the program, as defined by each individual program.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical Overall Participation Rates for 100 Eligible Patients Using Program-Reported Survey Responses. As can be seen, the cumulative effective of the quality gap at each stage (hospital referral, clinic referral, enrollment and completion) results in only 30 out of 100 patients moving from a qualifying diagnosis all the way through cardiac rehabilitation completion. Rates are defined as per Figure 1 and the manuscript text. CR = Cardiac Rehabilitation.

We found only weak correlation between the presence of QI projects and program-reported program participation rates (data not shown in tables.) When comparing programs reporting without QI projects to programs performing such projects, QI projects were not associated with significantly improved hospital referral (+4%, from 57 to 61%, p = 0.30,) office/clinic referral (+7%, from 38% to 45%, p = 0.06), enrollment (-5%, from 65 to 60%, p = 0.06), or completion rates (+ 0.5%, from 71 to 71.5%, p = 0.90).

Discussion

In this national survey of 290 AACVPR-registered program directors, we found that, although programs are aware of substantial participation rate gaps, monitoring of participation rates is suboptimal, quality improvement initiatives are infrequent, and proven strategies for increasing patient participation are inconsistently utilized. The outpatient/clinic setting has the lowest reported referral rates, lowest monitoring of rates, and lowest utilization of systematic referral. However, inpatient referral and monitoring is still far from ideal. We found that many programs are not utilizing either a phase I program, a systematic referral or a liaison as part of their hospital referral strategy; all of which are key factors known to increase CR referral. For the most part, this was not because of lack of control or awareness of referral strategies. Rather, 90% and 70% of programs could answer detailed questions about inpatient and outpatient referral techniques, respectively, with only about ~10% of programs reporting being unable to measure their participation rates. As a result, while programs are aware of participation gaps, appear able to monitor rates, and can probably institute process changes, substantial gaps remain between current and ideal CR program participation rates in both the inpatient and outpatient settings.

Taken together, these findings suggest that there is a large opportunity for CR programs to improve the care of patients in need of CR and that CR programs could be doing more to recruit and retain patients. Furthermore, our results suggest that if every CR program nationally implemented known effective strategies for patient recruitment, the national CR participation gap would shrink significantly. Such an achievement would likely produce substantial gains in the cardiovascular health and wellness of the nation. Given the known cost-effectiveness of CR,17 efforts at improving participation rates would also likely be a wise investment of time and resources for hospitals, medical systems, and accountable care organizations. Such efforts would also help organizations meet performance measures and national guidelines.1-3 Given the central importance of improving CR participation rates, AACVPR leadership may want to consider the performance of QI projects as part of the program certification process.

Although there appears to be a large opportunity for quality improvement in CR, one potential reason that programs may not be utilizing effective strategies or performing QI projects is program capacity restraints.16 Without enough staffing and physical resources necessary to accommodate an increased number of patients, program directors may have little motivation to perform QI projects with the goal to increase patient participation because they are already running at or near capacity. Consequently, although we did not assess this specifically, it seems possible that underutilization of effective recruitment strategies seen in our survey may be a consequence of program capacity restraints.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a national survey of the utilization of evidence-based CR referral and recruitment strategies has been performed in the United States. Although several national surveys have recently been performed, none of these has focused on the prevalence and opportunities for improvement in CR participation rates. For example, Zullo et al, surveyed CR programs in Ohio and found substantial between-program variations in AACVPR recommended core CR components.18 Similarly, Kaminsky et al.19 surveyed 137 United States CR program and asked about basic program features and patient demographics. Neither study addressed the question of referral and enrollment rates (which is arguably the largest quality problem in CR.) Lastly, Grace et al. surveyed CR providers in Canada, noted low participation rates, and also found that part of the implementation problem was CR staff skepticism towards empirically proven enrollment strategies.20 Although performed in Canada, these findings, in combination with our survey, suggest that additional education of CR programs with an increased focus on evidence-based effective strategies is warranted.

It is unclear why program QI projects were only weakly related to program-reported CR participation rates. It is possible that QI projects carried out by our survey respondents did not have an impact on CR participation. However, given that several different QI projects in CR have previously been demonstrated to effectively increase referral, enrollment, and completion,13, 21-23we believe there is not some inherent flaw with QI efforts in CR. Similarly, this finding may reflect an important need among AACVPR programs for increased training in how to effectively perform QI projects. Alternately, this finding may have been due to limitations in our survey technique and the use of program-reported (vs. measured/validated) participation rates. Furthermore, we did not assess the nature, focus, or perceived success of the performed QI projects, nor did we assess short term versus long-term outcomes of the projects. As a result, this is a major limitation to our study. It is possible, for instance, that a specific QI project improved participation but only on a short-term basis. Based upon prior literature, key factors that seem to differentiate successful from unsuccessful QI projects appear to be 1) high levels of goal sharedness, 2) strong administrative support, 3) strong physician leadership, 4) the use of credible data for feedback, and 5) the clear use of improvement initiatives.24 Since none of these factors were assessed in our survey, we are unable to assess the underlying reasons for “success” or “failure” of the QI projects reported by our survey respondents. Given our finding that QI projects may not be related to CR participation, a significant opportunity exists for future research to explore this issue in greater detail.

Importantly, we were able to survey only AACVPR registered program directors, rather than every CR program in the US (regardless of AACVPR registration). Based on data from 2003, non-AACVPR registered programs represent more than 70% of total US CR programs.25 Although little is known about these programs, they are generally believed to be smaller, have fewer full time employees, fewer full-time managers, and appear less likely to seek AACVPR certification. With decreased program size and dedicated leadership time, it is presumed that these programs are less likely to implement new referral strategies, retention programs, or quality improvement projects. As a result, we believe our survey most likely overestimates the actual national quality awareness and improvement projects when considering all CR programs in the US, because we surveyed only large, well established programs that seek AACVPR certification. As a result, this suggests that the true quality gap is even larger that reported here. Furthermore, this idea is substantiated in that program-reported participation rates among our surveyed AACVPR programs (Figure 1) are all higher than those reported in the medical literature.4, 5, 26

Other important limitations of our study include a relatively low survey response rate, although our previous analyses showed that respondents appeared reasonable representative of the AACVPR membership.16 Additionally, we were unable to validate any program-reported participation rates which limited our confidence in these outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, our survey highlights current gaps in the use of effective strategies that have been shown to improve delivery of CR, and thereby identifies opportunities for quality improvement by CR programs in the United States. It is likely that at least some of these opportunities are within the reach of most hospitals, clinics, and CR programs. It is equally likely that significant challenges exist that will limit the full implementation of effective CR participation strategies (i.e., competing demands on the time of clinicians and information technology support teams). CR professionals can contribute to efforts to improve CR participation rates and related patient outcomes by working collaboratively with local hospitals and clinics to implement proven, evidence-based CR participation strategies in their communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jonah Gorski, BA and the AACVPR leadership for allowing and assisting in this survey.

Funding Sources: The Mayo Clinic Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Program provided funding to cover the modest cost of the survey incentive. No other funding was used to support this work.

Footnotes

All authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

All other authors report no financial, personal, or affiliation conflicts of interest relevant to the subject of this manuscript.

Disclosures

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Lichtman are past presidents of the AACVPR, but neither received (nor currently receive) any compensation for their time and efforts.

References

- 1.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: Executive Summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 Dec 6;58(24):2584–2614. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients With Coronary and Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 Update A Guideline From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation Endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 Nov 29;58(23):2432–2446. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Pina IL, Spertus J. AACVPR/ACCF/AHA 2010 update: performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services: a report of the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Performance Measures for Cardiac Rehabilitation) Circulation. 2010 Sep 28;122(13):1342–1350. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f5185b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007 Oct 9;116(15):1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Receipt of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation among heart attack survivors--United States, 2005. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2008 Feb 1;57(4):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunlay SM, Witt BJ, Allison TG, et al. Barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation. American heart journal. 2009 Nov;158(5):852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravely-Witte S, Leung YW, Nariani R, et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment rates. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2010 Feb;7(2):87–96. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins RO, Murphy BM, Goble AJ, Le Grande MR, Elliott PC, Worcester MU. Cardiac rehabilitation program attendance after coronary artery bypass surgery: overcoming the barriers. The Medical journal of Australia. 2008 Jun 16;188(12):712–714. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balady GJ, Ades PA, Bittner VA, et al. Referral, Enrollment, and Delivery of Cardiac Rehabilitation/Secondary Prevention Programs at Clinical Centers and Beyond: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Nov 14; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b21e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arena R, Williams M, Forman DE, et al. Increasing Referral and Participation Rates to Outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation: The Valuable Role of Healthcare Professionals in the Inpatient and Home Health Settings: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Jan 30;125(10):1321–1329. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318246b1e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King M, Bittner V, Josephson R, et al. Medical director responsibilities for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2012 update: a statement for health care professionals from the American Association for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the American Heart Association. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012 Nov-Dec;32(6):410–419. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31826c727c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ades PA, Waldmann ML, McCann WJ, Weaver SO. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation in older coronary patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992 May;152(5):1033–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pack QR, Mansour M, Barboza JS, et al. An early appointment to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation at hospital discharge improves attendance at orientation: a randomized, single-blind, controlled trial. Circulation. 2013 Jan 22;127(3):349–355. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.121996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harkness K, Smith KM, Taraba L, Mackenzie CL, Gunn E, Arthur HM. Effect of a postoperative telephone intervention on attendance at intake for cardiac rehabilitation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2005 May-Jun;34(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grace SL, Russell KL, Reid RD, et al. Effect of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on utilization rates: a prospective, controlled study. Archives of internal medicine. 2011 Feb 14;171(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pack QR, Squires RW, Lopez-Jimenez F, et al. The current and potential capacity for cardiac rehabilitation utilization in the United States. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2014 Sep-Oct;34(5):318–326. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong WP, Feng J, Pwee KH, Lim J. A systematic review of economic evaluations of cardiac rehabilitation. BMC health services research. 2012;12:243. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zullo MD, Jackson LW, Whalen CC, Dolansky MA. Evaluation of the recommended core components of cardiac rehabilitation practice: an opportunity for quality improvement. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2012 Jan-Feb;32(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31823be0e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008 Feb 26;117(8):1028–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [January, 20, 2014];Proposed Decision Memo for Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) Programs - Chronic Heart Failure (CAG-00437N) Available at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=270&bc=AAAAAAAAAAQAAA%3d%3d&.

- 21.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Jul;64(7):749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twisk J. Applied Multilevel Analysis: A Practical Guide. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. A qualitative study of increasing beta-blocker use after myocardial infarction: Why do some hospitals succeed? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001 May 23-30;285(20):2604–2611. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curnier DY, Savage PD, Ades PA. Geographic distribution of cardiac rehabilitation programs in the United States. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. 2005 Mar-Apr;25(2):80–84. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients: findings from the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines Program. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009 Aug 4;54(6):515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.