Abstract

Objective

To incorporate preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and other biomedical or intensive behavioral interventions into the care of injection drug users, healthcare providers need validated, rapid, risk screening tools for identifying persons at highest risk of incident HIV infection.

Methods

To develop and validate a brief screening tool for assessing the risk of contracting HIV (ARCH), we included behavioral and HIV test data from 1904 initially HIV-uninfected men and women enrolled and followed in the ALIVE prospective cohort study between 1988 and 2008.

Using logistic regression analyses with generalized estimating equations (GEE), we identified significant predictors of incident HIV infection, then rescaled and summed their regression coefficients to create a risk score.

Results

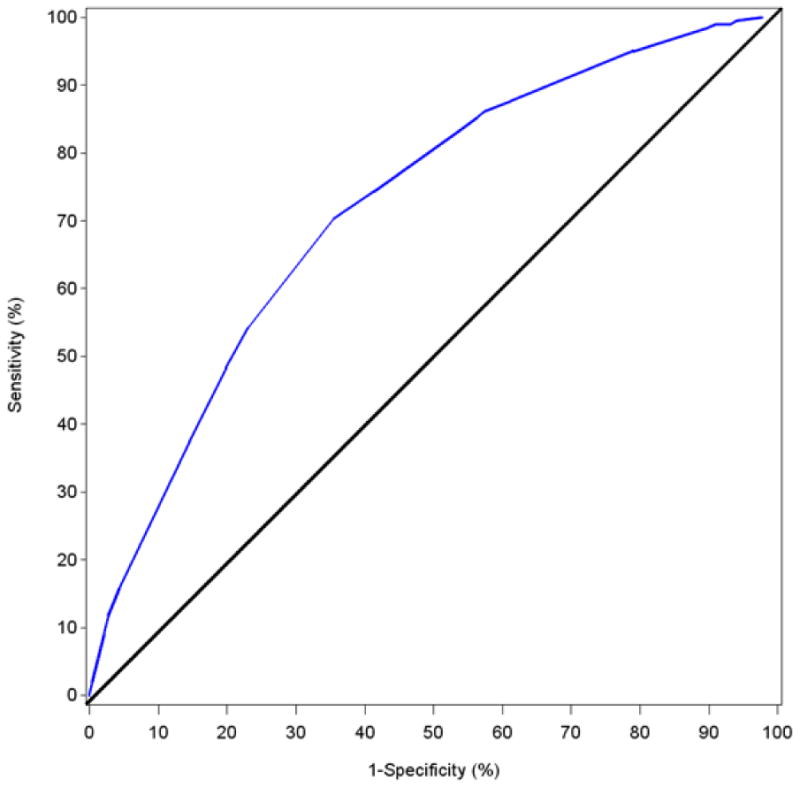

The final logistic regression model included age, engagement in a methadone maintenance program, and a composite injection risk score obtained by counting the number of the following five behaviors reported during the past six months: injection of heroin, injection of cocaine, sharing a cooker, sharing needles, or visiting a shooting gallery. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.720, possible scores on index ranged from 0 to 100 and a score ≥46 had a sensitivity of 86.2% and a specificity of 42.5%, appropriate for a screening tool.

Discussion

We developed an easy to administer 7-question screening tool with a cutoff that is predictive of incident HIV infection in a large prospective cohort of injection drug users in Baltimore. The ARCH-IDU screening tool can be used to prioritize persons who are injecting illicit drugs for consideration of PrEP and other intensive HIV prevention efforts.

Keywords: HIV, risk, IDU, PrEP, screening

Background

SAMHSA's 2009 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicated that 425,000 persons aged 12 or older reported having used a needle to inject heroin (240,000), cocaine (166,000), methamphetamine (165,000), or other stimulants (95,000) during the year prior to interview. Moreover, 13% of injection drug users (IDU) reported having used a needle that they knew or suspected someone else had used before them the last time they used a needle to inject drugs(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

The number of past year heroin users by any route of use increased 44% between 2007 (373,000) and 2012 (669,000), and the number of persons with heroin dependence or abuse in 2012 (467,000) was approximately twice the number in 2002 (214,000). Meanwhile, the number of adolescents and adults reporting current use of cocaine (1.6 million) in 2012 were fewer than in 2006 (2.4 million) as were the number of past month methamphetamine users who also decreased from 731,000 in 2006 to 440,000 in 2012(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013).

A CDC meta-analysis of four large national survey estimates of the number of IDU found that an estimated 774,434 persons aged 13 or older injected any illicit drug in the prior year. In addition, the authors estimated 3,648 IDU in the 50 US states received a diagnosis of HIV infection in 2011(Lansky et al., 2014). CDC's National HIV Behavior Surveillance System (NHBS), a respondent-driven survey of IDU in 20metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs)1 in 2009, found that 58% reported sharing injection equipment and that 19% had participated in a behavioral intervention in the prior year(Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2012a).

Of the 3,648 IDU with new HIV diagnoses in 2011, 47% were non-Hispanic African- Americans, 25% were Hispanic, and 24.5% were non-Hispanic whites; 38% were female and 62% were male(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Among the 47,500 estimated incident infections in 2010, 10% occurred among IDU, including 4% among men who have sex with men (MSM) who also injected drugs. There has been no significant change in the number of new HIV infections among IDU in recent years (2007-2010)(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

While HIV infection remains one serious health consequence of injection drug use, drug overdose is the most common cause of death among injection drug users, among both those who inject opiates (e.g., heroin) and those who inject stimulants (e.g., methamphetamine) (Mathers et al., 2013). However, deaths resulting from trauma/accidents and from HIV and other infectious diseases are also common(D. Vlahov et al., 2008),(Evans et al., 2012).

To reduce the risk of HIV infection and other serious health consequences of injection drug use, access to and utilization of clinical preventive health care is increasingly indicated. This includes medication-assisted opiate agonist therapy(Bruce, Kresina, & McCance-Katz, 2010) with methadone, buprenorphine, or buprenorphine with naloxone; overdose prevention through prescription of naloxone; medication-based treatment of mental health conditions: hepatitis B vaccination; and diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases acquired by injection practices (e.g., endocarditis, hepatitis B or C, HIV).

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of daily oral use of antiretroviral medication in the prevention of HIV acquisition among IDU(Choopanya et al., 2013), MSM(Grant et al., 2010), and heterosexually active men and women(Baeten et al., 2012; Thigpen et al., 2012). Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with a pill containing co-formulated tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine is now a recommended HIV prevention method for IDU(Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2013). Because the medications used for PrEP must be prescribed and monitored by a licensed clinician, it offers another opportunity to engage IDU in clinical care. However, because PrEP is only indicated for IDU at substantial risk of HIV acquisition, clinicians need tools to help them assess which patients may be most appropriate to discuss PrEP with.

Several brief tools are currently used in clinical care settings to screen for alcohol dependence(Chan, Pristach, & Welte, 1994; Volk, Steinbauer, Cantor, & Holzer, 1997), cognitive mental status(Crum, Anthony, Bassett, & Folstein, 1993), depression(Sharp LK, 2002), suicide risk(Gaynes et al., 2004), and other conditions. These screening tools identify patients in need of further evaluation for clinical diagnosis to guide treatment plans. To support the introduction and broader implementation of PrEP for IDU, a brief screening tool can assist clinicians to systematically determine which patients may be at substantial risk of HIV acquisition.

Methods

Study Population

We identified a large, ongoing, prospective cohort study – the AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience (ALIVE) study(David Vlahov, Anthony, & Muiioz, 1991; David Vlahov, Anthony, Muñoz, & Margolick, 1991) – which includes current and former injection drug users in Baltimore, MD. Briefly, from 1988-2008, 2643 current and former IDUs from the Baltimore metropolitan area were recruited, as previously described. At enrollment, participants had to report injection drug use in the prior 11 years, be free of AIDS, and 18 years of age or older. Additional recruitment was done in 1994-95, 1998, and 2005-08 to replenish the cohort. The ALIVE study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent. Individuals have been followed semi-annually; at each visit, a questionnaire on drug use, sexual behaviors, and health status is administered to participants and blood is collected and tested to document HIV infection status. For these analyses, we used the behavioral data reported at a given study visit to assess predictive accuracy for identifying HIV status at the subsequent visit. We excluded observations with more than eight months between visits, and any visits after HIV seroconversion occurred. Our analyses include 1904 ALIVE study participants who were enrolled between 1988 and 2008 and who were HIV seronegative at baseline (see Supplement Figure S1, Data Inclusion/Exclusion Diagram).

Measures

Self-reported risk behaviors, including sexual activity, alcohol and drug use, and occurrence of sexually transmitted disease (STDs) were assessed by use of standard interviewer-administered questionnaires at baseline and every six months thereafter. HIV-1 status was determined at each study visit by a standard HIV-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; enzyme immunoassay– positive tests underwent confirmatory Western blot testing.

A review of the questionnaires in the ALIVE study was conducted to select questions about injection drug use practices and STD diagnoses that were asked consistently over the two-decade study period. We limited our analyses to variables drawn from questions that were answerable during a single clinical encounter (e.g., self-report of STD diagnoses). Three demographic variables (age, educational status, and homeless in the prior six months) and ten HIV risk behavior variables reported for the prior six months (injecting heroin, injecting cocaine, sharing a cooker, sharing needles, visiting a shooting gallery, participation in a methadone maintenance program, identifying as an MSM, having sex with an IDU partner, the number of heterosexual sex partners, and reporting an STD) were identified for potential use in the screening index. As several drug use variables were related to injection practices and were correlated with each other (i.e., injected cocaine, injected heroin, shared cooker, shared needles, and used shooting gallery), we explored combining them into a composite injection variable for scoring purposes. The composite score ranges from 0 to 5 and sums all five non-missing injection-related risk behaviors. If the 5 five items were all missing, the score was missing.

Statistical Analysis

We used the ALIVE data to model which combination of reported risk behaviors at each visit best predicted HIV status at the subsequent study visit (i.e., predicting short- term seroconversion risk). We used logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for the repeated measurements within a subject.

Our HIV-1 prediction model was built using a two-step process. First, we used the complete dataset to fit univariable models for each of the candidate predictor variables. Variables with a p value ≤ 0.20 in their respective univariable model were considered as candidate variables in the multivariable model. We used a backward selection process and p-value < 0.05 criterion to select the final variables in the multivariable model. The second step involved using bootstrapping to perform internal validation of the multivariable model. Validation was performed using bootstrapping methods with backward elimination procedures because this procedure provides nearly unbiased estimates of predictive accuracy(Efron, 1983). We chose 200 bootstrap samples (with replacement) from the original dataset. For each bootstrap sample, we fit a full model using all candidate variables and then used backward elimination until all variables in the multivariable model were significant at (p <0.05). A summary concordance index (c index) based on bootstrap samples was presented to assess the validation of our final model(Harrell, Lee, & Mark, 1996). Any value for c index from 0.5 to 1 makes a sensible model. The higher the value, the better the prediction.

To obtain point scores for the HIV risk index from the final multivariable model we calculated the maximum individual score based on regression coefficients, rescaled it to 100, converted the coefficients to scores accordingly, and rounded them to the nearest integer. Finally, we summed the point values for all variables in the model to get a total ARCH-IDU index score and assessed performance characteristics of different score cutoffs for identifying HIV seroconversions by computing sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Results

We analyzed data collected from 22,105 ALIVE study visits conducted between July 1988 and June 2008 among 1904 persons without HIV infection at study enrollment. The majority (93.1%) of visits were contributed by non-Hispanic black participants. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the participants for demographic and behavioral variables by whether or not HIV infection was acquired during the study follow-up. 205 participants acquired HIV infection and 1699 participants did not acquire HIV infection during the follow-up period. The mean and median numbers of visits per person were 12.6 and 9.0, respectively, and the median follow-up time was 5.85 years (Interquartile range, 1.66-12.76 years).

Table 1. Baseline frequencies of candidate variables among injection drug users and univariate analyses of factors associated with final observed HIV status. ALIVE Study, Baltimore (1988-2008).

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline frequencies of candidate variables by final observed HIV status | Univariate analysis of factors associated with final observed HIV status | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Did not Acquire HIV Infection (N=1699*) | Acquired HIV Infection (N=205*) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | P value | Coefficients | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||||||

| Age | <.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| <30 | 273 (16.1) | 58 (28.3) | 1.9 | 7.0 | 3.8-12.8 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 30-<40 | 767 (45.1) | 111 (54.2) | 1.3 | 3.6 | 2.1-6.0 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 40-<50 | 514 (30.3) | 31 (15.1) | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.0-2.8 | ||

|

| |||||||

| >= 50 (REF) | 145 (8.5) | 5 (2.4) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Education | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| <Grade School | 44 (2.6) | 5 (2.4) | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4-3.3 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Grade School | 89 (5.2) | 14 (6.8) | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.7-3.0 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Some HS | 803 (47.3) | 112 (54.6) | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.9-2.3 | ||

|

| |||||||

| HS/GED | 529 (31.2) | 52 (25.4) | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | ||

|

| |||||||

| At least Some college (REF) | 233 (13.7) | 22 (10.7) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Homeless | 0.5 | 0.02 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 321 (24.5) | 35 (27.1) | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.2-2.4 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 992 (75.6) | 94 (72.9) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Injected Heroin | 0.07 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 1274 (75.7) | 142 (70.0) | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.6 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 408 (24.3) | 61 (30.1) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Injected Cocaine | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 1216 (72.3) | 171 (84.2) | 1.3 | 3.7 | 2.7-5.0 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 467 (27.8) | 32 (15.8) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Shared cooker | 0.08 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 988 (58.4) | 131 (64.9) | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.8-3.1 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 704 (41.6) | 71 (35.2) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Shared needles | 0.5 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 807 (47.7) | 101 (50.0) | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.6 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 884 (52.3) | 101 (50.0) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Used shooting gallery | 0.6 | 0.01 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 272 (16.1) | 36 (17.7) | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.3-3.1 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 1416 (83.9) | 167 (82.3) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Methadone maintenance | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes (REF) | 203 (12.0) | 8 (3.9) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| No | 1492 (88.0) | 195 (96.1) | 1.5 | 4.5 | 2.3-9.2 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Any sexually transmitted disease† | 0.003 | 0.05 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 72 (4.4) | 18 (9.2) | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.3-4.3 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 1582 (95.7) | 177 (90.8) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| MSM | 0.07 | 0.1 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 28 (1.7) | 7 (3.5) | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.1-7.2 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No(REF) | 1666 (98.4) | 196 (96.6) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Sex with an IDU | 0.5 | 0.009 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Yes | 691 (41.5) | 89 (44.1) | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.1-2.0 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No (REF) | 974 (58.5) | 113 (55.9) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Number of heterosexual sex partners | 0.3 | 0.06 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| 0-1 | 983 (58.3) | 111 (54.7) | -0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.9 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 2-4 | 504 (29.9) | 60 (29.6) | -0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.3 | ||

|

| |||||||

| >=5 (REF) | 200 (11.9) | 32 (15.8) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| Composite Injection Score** | 0.7 | <0.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| (REF) 0 | 267 (15.8) | 28 (13.8) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | ||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 156 (9.2) | 16 (7.9) | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.8-2.6 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 2 | 271 (16.0) | 33 (16.3) | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.7-3.9 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 3 | 336 (19.9) | 35 (17.2) | 1.1 | 3.1 | 2.1-4.7 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 4 | 464 (27.4) | 61 (30.1) | 1.2 | 3.4 | 2.3-5.2 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 5 | 199 (11.8) | 30 (14.8) | 1.6 | 4.7 | 2.8-8.1 | ||

|

| |||||||

Note: Behaviors and STDs were reported for the prior 6 months

STDs included were self-reported gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, warts, ulcers and trichomonas.

For some variables, the total of those who did and did not acquire HIV infection did not sum to the total N of study participants because of missing values.

Composite Score combines Injected Cocaine, Injected Heroin, Shared Cooker, Shared Needles and Used Shooting Gallery.

All candidate variables had p-values ≤ 0.2) in our analysis with and without inclusion of the composite injection variable included (Table 1 and were entered into the multivariable model selection.

The results of our first multivariable model (“6-level composite score”) are presented in Table 3. They indicated that the odds ratios comparing “2 vs 0”, “3 vs 0”, “4 vs 0” and “5 vs 0” were similar in magnitude. Therefore, we ran a second multivariable model (“3-level composite score”) with the composite score defined as 0, 1 and ≥ 2. The model estimates based on 3-level composite score are presented in the right side of Table 2. The c index for both the 6-level and 3-level composite scores was 0.700, which indicated a reasonably accurate prediction model.

Table 3. ARCH – IDU Risk Scoring Sheet.

| 1 | How old are you today (years)? | If <30 years, | score 38 | ――――――――― | ||

| If 30- 39 years, | score 24 | |||||

| If 40-49 years, | score 7 | |||||

| If ≥50 years, | score 0 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 2 | In the last 6 months, were you in a methadone maintenance program? | If yes, | score 0 | ――――――――― | ||

| If no, | score 31 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 3 | In the last 6 months, how often did you inject heroin? | If 1 or more times, | Injection sub-score 1 | ――――――――― | ||

| If 0 times, | Injection sub-score 0 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| In the last 6 months, how often did you inject cocaine? | If 1 or more times, | Injection sub-score 1 | ――――――――― | |||

| If 0 times, | Injection sub-score 0 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| In the last 6 months, how often did you share a cooker? | If 1 or more times, | Injection sub-score 1 | ――――――――― | |||

| If 0 times, | Injection sub-score 0 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| In the last 6 months, how often did you share needles? | If 1 or more times, | Injection sub-score 1 | ――――――――― | |||

| If 0 times, | Injection sub-score 0 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| In the last 6 months, how often did you visit a shooting gallery? | If 1 or more times, | Injection sub-score 1 | ――――――――― | |||

| If 0 times, | Injection sub-score 0 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Composite Injection Score | Add down the 5 injection subscores above | ――――――――― | ||||

| If 0, | score 0 | |||||

| If 1, | score 7 | |||||

| If 2, | score 21 | |||||

| If 3, | score 24 | |||||

| If 4, | score 24 | |||||

| If 5, | score 31 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Add down the three entries in the right column to calculate total score | ――――――――― TOTAL SCORE* |

|||||

To identify active IDU in their practice, we recommend clinicians ask all their patients a routine question: “Have you ever injected drugs that were not prescribed for you by a physician” (if yes), “When was the last time you injected any drugs?” Only complete IDU risk index if they have injected any nonprescription drug in the past 6 months.

If score is 46 or greater, evaluate for PrEP or other intensive HIV prevention services for IDU.

If score is 45 or less, provide indicated standard HIV prevention services for IDU.

Table 2. Initial Multivariable Model Estimates.

| 6-level Composite Score | 3-level Composite Score | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Coefficients | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Coefficients | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | <30 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 2.7-9.4 | <.0001 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 2.8-9.6 | <.0001 |

| 30-<40 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.5-4.5 | 0.0004 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.6-4.6 | 0.0003 | |

| 40-<50 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.8-2.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.8-2.4 | 0.2 | |

| >=50 (REF) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - | |

| Methadone Maintenance | No | 1.3 | 3.8 | 1.8-7.9 | 0.0005 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 1.8-8.1 | 0.0004 |

| Yes(REF) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - | |

| Composite Injection Score | 0 (REF) | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - | 0.0 | 1.0 | - | - |

| 1 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.5 | 0.4 | |

| 2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.5-3.6 | 0.0001 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.9-3.8 | <.0001 | |

| 3 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.8-4.2 | <.0001 | |||||

| 4 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.8-4.2 | <.0001 | |||||

| 5 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 2.0-6.2 | <.0001 | |||||

OR= Odds Ratio

CI = confidence interval

In summary, the final multivariable prediction model includes age, methadone maintenance and the composite injection score. The composite injection score combined information on injected cocaine, injected heroin, shared cooker, shared needles, and use of a shooting gallery.

The area under the ROC curve for the 6-level (Figure 1) composite score was 0.720 and 3-level composite score was 0.716 (figure not included). Because all six questions need to be asked regardless of which composite score was used, we elected to use the 6-level composite score to assess a cutoff score with appropriate sensitivity and specificity for a screening tool. We selected a cutoff score based on parameter coefficients of ≥46 to identify IDU at substantial risk of HIV infection. Of 22,105 study visits, at 12,711 (57.8%) visits, participants scored at or above this cutpoint. This cutoff was associated with a sensitivity of 86.2% (i.e., of those who became infected by the next study visit, 86.2% had an ARCH-IDU score of 46 or greater). Specificity at a cutoff of ≥46 was 42.5% (i.e., of those who remained HIV negative at the next study visit, 42.5% had an ARCH-IDU score <46 (see Supplementary Digital Content, Table S1, Sensitivity and Specificity of Cutoff Scores).

Figure 1. ROC Curve for ARCH-IDU Score.

While 90.3% of all ALIVE study participants had an ARCH-IDU score at or above the cutoff during at least one visit during follow-up, there was substantial variability in scores at visits over time; 56.8% of participants had scores of 46 or greater for >75% of their study visits. While sharing of needles remained high throughout the observation period, mean ARCH-IDU scores ≥46 declined as did other component variables (see Supplementary Digital Content, Figure S2, ARCH IDU components and score by calendar year of observation).

We next compared the main parameters from our results for the ARCH-IDU to the ARCH-MSM(Smith, Pals, Herbst, Shinde, & Carey, 2012) (previously called HIRI-MSM). The area under the curve (AUC) values were similar in the analyses conducted for both screening tools. With the cutoff points specified for each tool, the two ARCH tools provided similar sensitivity and specificity to predict a person's observed risk for incident HIV infection (see Supplementary Table S2, comparison between MSM and IDU ARCH screening tools).

Last, we developed an administration format for use by clinicians, adapting the questions used in the ALIVE study to allow efficient capture of the data and facilitate scoring (Table 3).

Discussion

To develop a brief index for clinical use to screen for risk of incident HIV infection among IDU, we analyzed data from a large longitudinal study of IDU in Baltimore with periodic behavioral assessments and HIV testing. Weighted responses to two items (age and recent methadone maintenance) and a five-item composite risk variable yielded a scoring system that had good sensitivity for identifying HIV seroconvertors. Use of the brief index by care providers with their patients can help in selecting a subset of IDU who may need to have more extensive behavioral assessment regarding specific injection drug-use behaviors that increase their risk for HIV acquisition. The sensitivity and specificity results obtained in developing this brief index perform similarly to a previous predictive HIV risk index developed for MSM(Smith et al., 2012).

To use ARCH-IDU, it will first be necessary for clinicians to identify which patients have prior or current injection drug use through sensitive history-taking. Because acknowledging illicit drug use can be difficult for some patients(Fendrich, Mackesy-Amiti, & Johnson, 2008), we recommend that clinicians routinely ask a straightforward question of all adult and adolescent patients as follows: “Have you ever injected drugs that were not prescribed for you by a physician?” If the patient acknowledges past injection use, then the clinician should ask, “When was the last time you injected any drugs?” If the patient has injected illicit drugs in the past six months, the 7 ARCH-IDU questions can be administered and scored.

For all persons who have recently injected drugs, health risk-reduction messages are appropriate along with provision of, or facilitated referral to, appropriate substance abuse and/or mental health services. For those not ready or able to enter a drug treatment program, priority should be given to the provision of information about how to access sterile needles and syringes(Des Jarlais et al., 2000), and where to access peer-support programs (e.g., 12-step program). In addition to these services for all injectors(Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2012b), clinicians should consider prescribing PrEP for any IDU with a score of 46 or greater, discuss PrEP use with the patient, and decide together whether or not to use this HIV prevention method. Because injection practices are dynamic over time, repeated screening for risk of HIV acquisition will be more useful than a single screening.

There are limitations to the analysis used to develop ARCH-IDU. The data were collected from an observational study of IDU in a single city in the U.S. This population is not representative of all IDU with incident HIV infections nationally. The data used from the ALIVE study span over two decades with most seroconversions occurring more than a decade ago; risk factors for HIV acquisition may have changed over time including highly effective antiretroviral treatment, and availability of opioid agonist therapies and syringe service program. However, more recent data appropriate to perform these analyses for IDU in other cities or cohorts are not readily available.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has conducted usability testing with a web-based early version of ARCH-IDU to assess both user and provider acceptability. Both non-clinical HIV prevention providers and clinicians found it to be brief and easily completed (unpublished data). The ARCH tools can be used for either patient self-administration or clinician administration in any of several formats: paper and pencil, through a web application, or as a smartphone application(Jones et al., 2014). The CDC is currently developing risk screening tools for use with heterosexual men and women, and with HIV-discordant couples.

In addition to using these risk screening tools for providing prevention care to patients, they could also be useful for researchers in analysis of HIV risk in epidemiologic cohorts and in behavioral intervention trials.

Conclusions

We believe the ARCH-IDU can be useful to assist primary care, substance abuse treatment, and other providers to routinely ask questions that will help them identify unrecognized IDU in their practice and, for both newly recognized and known IDU, to quickly screen for factors that indicate a greater risk of acquiring HIV infection. The ARCH-IDU is designed to take only a few minutes to complete and can accommodate the documented time pressures under which providers deliver recommended preventive screening and care(Yarnall, Pollak, Ostbye, Krause, & Michener, 2003).

Periodic use of screening provides an opportunity for providing clinical care for multiple health concerns(Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2012b), beginning with substance abuse treatment and mental health services when ready. All IDU should be provided with regular HIV testing, screening for hepatitis B and C infection (and vaccination for hepatitis B if not immune). In addition, because IDU may also be sexually active, the provision of basic sexual risk-reduction counseling and condom provision is also indicated(Meader et al., 2013), especially for those who inject stimulants (e.g., cocaine or methamphetamine) or who trade sex for drugs(Strathdee & Stockman, 2010). In this context, the unique drug treatment and reproductive health service needs of women who inject drugs will need to be specifically addressed(Magnus et al., 2013). The NHBS survey found that 69% of IDU reported vaginal sex without a condom, 23% reported heterosexual anal sex without a condom, and 46% reported more than one opposite sex partner in the prior year(Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2012a). A unique feature of PrEP is that it effectively reduces both sexual and injection risk as a single intervention. PrEP delivery could also be integrated with medication-assisted drug treatment(Edelman & Fiellin, 2013).

It is critical that the subset of IDU most at risk for becoming HIV infected be provided with drug treatment, access to sterile injection equipment, and consideration of PrEP provision if we are to lower the rate of new HIV infections occurring among them.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

COI: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest

A geographic entity defined by the US Census Bureau that comprises a core urban area and one or more adjacent counties that have a high degree of social and economic integration with the urban core. See http://www.census.gov/population/metro/

References

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, Celum C. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Kresina TF, McCance-Katz EF. Medication-assisted treatment and HIV/AIDS: aspects in treating HIV-infected drug users. AIDS. 2010;24(3):331–340. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833407d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., & Prevention. HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among injecting drug users - 20 cities, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012a;61(8):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., & Prevention. Integrated prevention services for HIV infection, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis for persons who use drugs illicitly: summary guidance from CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012b;61(RR-5):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., & Prevention. Update to Interim Guidance for Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for the Prevention of HIV Infection: PrEP for injecting drug users. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(23):463–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/index.htm#supplemental. [Google Scholar]

- HIV Survellance Report. Vol. 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWK, Pristach EA, Welte JW. Detection by the CAGE of alcoholism or heavy drinking in primary care outpatients and the general population. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6(2):123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M Bangkok Tenofovir Study, G. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-Based Norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by Age and Educational Level. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269(18):2386–2391. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03500180078038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Friedmann P, Titus S, Aviles E, Deren S, Monterroso E. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1992-1997: evidence for a declining epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(3):352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman EJ, Fiellin DA. Moving HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis into clinical settings: lessons from buprenorphine. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1 Suppl 2):S86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Estimating the Error Rate of a Prediction Rule - Improvement on Cross-Validation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1983;78(382):316–331. doi: 10.2307/2288636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JL, Tsui JI, Hahn JA, Davidson PJ, Lum PJ, Page K. Mortality Among Young Injection Drug Users in San Francisco: A 10-Year Follow-up of the UFO Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175(4):302–308. doi: 10.1093/Aje/Kwr318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP. Validity of self-reported substance use in men who have sex with men: comparisons with a general population sample. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(10):752–759. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, Frame P, Klein J, Lohr KN. Screening for Suicide Risk in Adults: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(10):822–835. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, Glidden DV. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15(4):361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Stephenson R, Smith DK, Toledo L, La Pointe A, Taussig J, Sullivan PS. Acceptability and willingness among men who have sex with men (MSM) to use a tablet-based HIV risk assessment in a clinical setting. SpringerPlus. 2014;3(1):708. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, Holtzman D, Wejnert C, Mitsch A, Crepaz N. Estimating the Number of Persons Who Inject Drugs in the United States by Meta-Analysis to Calculate National Rates of HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Infections. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M, Kuo I, Phillips G, II, Rawls A, Peterson J, Montanez L, Greenberg A. Differing HIV Risks and Prevention Needs among Men and Women Injection Drug Users (IDU) in the District of Columbia. Journal of Urban Health. 2013;90(1):157–166. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(2):102–123. doi: 10.2471/Blt.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meader N, Semaan S, Halton M, Bhatti H, Chan M, Llewellyn A, Des Jarlais DC. An international systematic review and meta-analysis of multisession psychosocial interventions compared with educational or minimal interventions on the HIV sex risk behaviors of people who use drugs. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):1963–1978. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0403-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp LK LK, L M. Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings. American Family Physician. 2002;66(6):1001–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Pals SL, Herbst JH, Shinde S, Carey JW. Development of a clinical screening index predictive of incident HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(4):421–427. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318256b2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Stockman JK. Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: current trends and implications for interventions. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2010;7(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Injection Drug USe and Related Risk Behaviors, 2006-2008. National Survey on Drug Use and Health : the NASDUH Report 2009. 2009 Retrieved 22 October 2013, from http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/139/139IDU.htm.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. 2013 Retrieved 22 October 2013, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm.

- Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, Brooks JT. Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Heterosexual HIV Transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Anthony J, Muiioz A. The ALIVE StudyA longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in intravenous drug users: description of methods and characteristics of participants. NIDA ResMonogr. 1991;109:75–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Muñoz A, Margolick J. The ALIVE study: A longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in intravenous drug users: Description of methods. Journal of Drug Issues. 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Wang C, Ompad D, Fuller CM, Caceres W, Ouellet L Study, C. I. D. U. Mortality risk among recent-onset injection drug users in five US Cities. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43(3-4):413–428. doi: 10.1080/10826080701203013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk RJ, Steinbauer JR, Cantor SB, Holzer CE. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screen for at-risk drinking in primary care patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Addiction. 1997;92(2):197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall KSH, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary Care: Is There Enough Time for Prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.