Abstract

Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs16754, has been considered as an independent prognostic factor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and renal cell carcinoma. However, its biological role in breast cancer has not been reported. To test whether WT1 SNPs can be used as a molecular marker in order to improve the risk stratification of breast cancer, we performed a case-control study including 709 female sporadic breast cancer patients and 749 female healthy control subjects in the Southeast China. Five WT1 SNPs (rs16754, rs3930513, rs5030141, rs5030317, rs5030320) were selected and determined by polymerase chain reaction-ligase detection reaction to assess their associations with breast cancer risk. Results showed the distributions of the alleles of these WT1 SNPs were consistent with data from Chinese population as suggested by the International HapMap Project. Individuals with the minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 showed a significant decrease of breast cancer risk in codominant model (OR = 0.6370, 95% CI: 0.4260-0.9520 for rs16754; OR = 0.5940, 95% CI: 0.3890-0.9070 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5870, 95% CI: 0.3850-0.8960 for 5030320, respectively) and recessive model. Stratified analyses showed the protective effects were more evident in the subjects with age ≤ 50 years or in pre-menopausal status. To explore the potential mechanism, we conducted bioinformatics genotype-phenotype correlation analysis, and found that the mRNA expression level for homozygous rare allele of WT1 gene was lower than that in wild-type and heterozygous group (P = 0.0021) in Chinese population. In summary, our findings indicated that minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 are associated with reduced risk of breast cancer, suggesting that WT1 SNPs may be a potential biomarker of individualized prediction of susceptibility to breast cancer. However, large prospective and molecular epidemiology studies are needed to verify this correlation and clarify its underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: WT1, polymorphism, breast cancer, susceptibility, risk

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 1.67 million newly diagnosed cases in 2012 accounting for 25% of all cancers, and it is the most frequent cause of cancer death in women in less developed regions (324,000 deaths, 14.3% of total) [1]. It is reported that breast cancer has become the major burden of the health for Chinese women [2], and approximately 12.2% of all newly diagnosed breast cancers and 9.6% of all deaths from breast cancer worldwide occurred in China [3]. It is well-known that breast cancer has a complex pathogenesis affected by many epidemiological, genetic, and epigenetic factors [4-8]. For genetic factors, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of candidate genes have been believed to be responsible for a large percentage of breast cancers [8,9].

The Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1), located at chromosome 11p13, was firstly cloned in 1990 as a suppressor in Wilms’ tumor [10-12], and plays an important role in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, organ development and the maintenance of several adult tissues [13-16]. Despite its role in Wilms’ tumor, a growing body of evidences indicated that WT1 might play an oncologic role in hematologic malignancies and a variety of solid tumors, and over-expression of WT1 indicated worse outcomes for patients with these cancers [17-27].

Sequencing analysis demonstrated that WT1 mutations were found in sporadic Wilms’ tumor [28] as well as urogenital abnormalities, such as Denys-Drash syndrome and Frasier syndrome [29,30]. In addition, WT1 mutations occurred in approximately 15% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [31], and correlated with poor outcomes in these patients [32-34]. Most recently, rs16754, a WT1 SNP in exon 7, was shown to predict significantly improved outcomes in patients with favorable-risk pediatric AML [35], cytogenetically normal AML [36] and clear cell renal cell carcinoma [37], which suggested that it might be biologically involved in the expression process of WT1 [35]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the potential roles of WT1 SNPs in breast cancer have not been clarified.

To explore whether WT1 SNP genotypes are associated with the risk of breast cancer in females, we carried out a case-control study involving 709 breast cancer patients and 749 healthy controls in the Southeast China. A total of five WT1 SNPs (rs16754, rs3930513, rs5030141, rs5030317, rs5030320) were selected as targets and characterized to assess their associations with breast cancer risk. We found minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 could predict low susceptibility to breast cancer, especially in the subjects with age equal or less than 50 years old or in pre-menopausal status.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 709 sporadic breast cancer patients and 749 healthy controls were enrolled from January 2012 to August 2013 from the Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China. All subjects were genetically unrelated Chinese females in Chongqing City and its surrounding regions. The inclusion criteria included histopathologically confirmed newly diagnosed breast cancer patients, who did not receive any kind of therapy before blood sampling, regardless of their age and pathological types. The exclusion criteria included pregnancy, being unwilling to undergo biopsy/surgical procedures, congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, severe hepatic or renal dysfunction and altered mental status other malignancies. The inclusion criteria for controls were healthy individuals and frequency matched to the cases for age (± 5 years), who were randomly selected from medical examination persons at the same hospital and during the same time. The study was approved by the Clinic Ethics Review Committee of Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

SNPs selection

One WT1 SNP, rs16754 in exon region was selected based on previously reports [35-37]. Bioinformatics analysis with Haploview software 4.2 (Mark Daly’s lab of Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, Britain) was performed to analyze the haplotype block based on the CHB (Chinese Han Beijing) population data of HapMap (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Four tag SNPs were found in the WT1 gene: rs3930513 and rs5030141 in intron region, rs5030317 and rs5030320 in the 3’UTR, with a minimum allele frequency (MAF) of 0.05 in CHB population.

DNA preparation and genotyping analysis

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). All DNA samples were stored in aliquots at -80°C for further use.

The selected 5 SNPs were genotyped with the method of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-ligase detection reaction (LDR) on an ABI Prism 377 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), as previously reported [38,39] with technical supports from the Shanghai Genesky Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). Two multiplex PCR reactions were designed. The first PCR reaction in 20 µl contained 1x PCR buffer, 3.0 mM Mg2+, 0.3 mM dNTP, 1 U of Hot-Start Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Dalian, Liaoning, China), 1 µl of primer mixture 1 and about 20 ng of genomic DNA. The second PCR reaction in 20 µl volume contained 1x GC Buffer I, 3.0 mM Mg2+, 0.3 mM dNTP, 1 U of Hot-Start Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Dalian, Liaoning, China), 1 µl of primer mixture 2 and about 20 ng of genomic DNA. The PCR program for both reactions was as follows: 95°C 2 min; 11 cycles x (94°C 20 s, 65°C -0.5°C/cycle 40 s, 72°C 1 min 30 s); 24 cycles x (94°C 20 s, 59°C 30 s, 72°C 1 min 30 s); 72°C 2 min; hold at 4°C. The two PCR products were equally mixed and purified by 1 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase’s digestion at 37°C for 1 hr and at 75°C for 15 min. The ligation reaction in 20 µl volume contains 1x ligation buffer, 80 U of Taq DNA Ligase, 1 µl of labeling oligo mixture, 2 µl of probe mixture and 5 µl of purified PCR product mixture. The ligation cycling program was 95°C 2 min; 38 cycles x (94°C 1 min, 56°C 4 min); hold at 4°C. And 0.5 µl of ligation product was loaded in ABI 3730xl and then the raw data were analyzed by GeneMapper 4.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sequences for PCR reaction and ligase reaction were described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Products size and primers of WT1 SNPs

| SNPs | Product size (bp) | PCR primer sequencea | Ligase reaction primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs16754 | 244 | rs16754F: TGTGCATCTGTAAGTGGGACAGC | rs16754RC: TTCCGCGTTCGGACTGATATCTGCCTGCAGGATGTGAGG |

| rs16754R: CCTGCCACCCCTTCTTTGGATA | rs16754RP: CGTGTGCCYGGAGTAGCCCTTTTTTTTT | ||

| rs16754RT: TACGGTTATTCGGGCTCCTGTCTGCCTGCAGGATGTGAGA | |||

| rs3930513 | 162 | rs3930513F: AAAGCTCGTGCCTCCTTCCACT | rs3930513FA: TACGGTTATTCGGGCTCCTGTCTGGTCCCGCATAGCTTGCAA |

| rs3930513R: TGGATAGCTCCCGCGTATGGTA | rs3930513FC: TTCCGCGTTCGGACTGATATCTGGTCCCGCATAGCTTGTAC | ||

| rs3930513FP: TCGGATAAGTCAAGTTSTCTTCCATCTTTTTT | |||

| rs5030141 | 277 | rs5030141F: TGGAGGTGCTCCTGGACATTTT | rs5030141FG: TCTCTCGGGTCAATTCGTCCTTCCAGAGTCCAGACGTCTGAAAATCG |

| rs5030141R: GAGCCTGACTGTTCGCAAGAGC | rs5030141FP: CTACGCTTGGTGACAATTTGGCTTTTTT | ||

| rs5030141FT: TGTTCGTGGGCCGGATTAGTCCAGAGTCCAGACGTCTGAAAACCT | |||

| rs5030317 | 153 | rs5030317F: TCAGGGGGACATGATCAGCTATG | rs5030317RG: TACGGTTATTCGGGCTCCTGTAAAAGCCCATTGCCATTTGTTC |

| rs5030317R: TGCCTGGAAGAGTTGGTCTCTG | rs5030317RC: TTCCGCGTTCGGACTGATATAAAAGCCCATTGCCATTTGTTG | ||

| rs5030317RP: TGGATTTTCTACTGTAAGAAGAGCCATAGCTTTT | |||

| rs5030320 | 278 | rs5030320F: CCCCTCCATTTGTGCAAGGA | rs5030320RC: TCTCTCGGGTCAATTCGTCCTTCATGCATTTCAAGCAGCTGAAGACAG |

| rs5030320R: GCCAGGCTGCTAACCTGGAAA | rs5030320RP: AATCAGAACTAACCAGTACCTCTGTATAGAAATCT | ||

| rs5030320RT: TGTTCGTGGGCCGGATTAGTCATGCATTTCAAGCAGCTGAAGACAA |

F indicates forward primer and R indicates reverse primer.

The genotyping was carried out blinded to group status. For quality control, a random sample accounting for 5% of the total participants were selected (n = 29) and genotyped twice by different researchers, yielding a reproducibility of 100%.

Correlation analysis for WT1 SNPs and mRNA expression levels

To elucidate possible underlying mechanisms, we analyzed the correlation between WT1 mRNA expression levels and variant genotypes as previous report [40] following the instructions of SNPexp (http://app3.titan.uio.no/biotools/tool.php?appsnpexp) [41]. The genotyping data were from the International HapMap Project (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [42] consisting of 3.96 million SNP genotypes from 270 individuals in four ethnic groups, and the data on transcript expression levels were from genome-wide expression arrays (47294 transcripts) for EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines of the same 270 HapMap individuals [41].

Statistical analysis

Chi-square and t tests were used to assess differences in the distributions of age and menopausal status between breast cancer cases and controls. Chi-square and fisher exact tests were used to explore the relationship between characteristics of breast cancer and the alleles and genotypes of WT1 gene. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested by a goodness-of-fit chi-square test to compare the expected genotype frequencies with observed genotype frequencies in healthy controls.

The associations between case-control status and each specific WT1 SNP were measured by the odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) using an unconditional logistic regression model with adjustments of age (continuous variable) and menopausal status (pre- or post-menopause). The ORs were performed for codominant model, dominant model, recessive model and allele contrast, respectively. Stratified analyses were done by age (≥ 50 or < 50 years old) and menopausal status (pre- or post-menopause) to evaluate the stratum variable-related ORs among the WT1 genotypes and alleles. When analysis was stratified by menopausal status, the ORs were calculated only with adjustment of age (continuous variable).

GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to explore the differences between the distributions of WT1 genotypes and mRNA expression level using one-way ANOVA test and make the graphic. All other kinds of tests were done using the SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All tests were all two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 709 female breast cancer cases and 749 controls were enrolled in this study. As shown in Table 2, the mean age was 48.3695 ± 10.3534 years for cases and 44.8144 ± 10.0065 years for controls (P < 0.0001). There were more women older than 50 years (35.12% vs. 25.77%, P = 0.0001) and more post-menopausal women (36.95% vs. 30.71%, P = 0.0117) in breast cancer group than in control group.

Table 2.

Demographics of the subjects included in the case-control study

| Characteristics | Controls (N = 749, %) | Cases (N = 709, %) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 44.8144 ± 10.0065 | 48.3695 ± 10.3534 | < .0001a |

| ≤ 50 | 556 (74.23) | 460 (64.88) | 0.0001b |

| > 50 | 193 (25.77) | 249 (35.12) | |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 519 (69.29) | 447 (63.05) | 0.0117b |

| Post-menopausal | 230 (30.71) | 262 (36.95) |

t test;

chi-square test.

Frequencies and features of WT1 SNPs in breast cancer patients and controls

The detailed information of these five SNPs was described in Table 3. The MAF of these SNPs in controls were 29.17% for rs16754, 26.84% for rs3930513, 31.71% for rs5030141, 27.70% for rs5030317, 27.70% for rs5030320, respectively. Similar frequencies of these SNPs were presented in breast cases. The distributions of the minor alleles were consistent with the data from CHB. The observed genotype frequencies of the five polymorphisms in controls conformed to the HWE (P = 0.1442 for rs16754, 0.3464 for rs3930513, 0.3369 for rs5030141, 0.1203 for rs5030317, 0.0826 for rs5030320, respectively).

Table 3.

Characteristics of WT1 SNPs selected in the case-control study

| Gene | SNP | Chr. | SNP Property | Allele | P for HWEa | MAF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Allele | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | CHBb (%) | ||||||

| WT1 | rs16754 | 11 | exon7 | G/A | 0.1442 | A | 29.17 | 26.59 | 25.20 |

| WT1 | rs3930513 | 11 | intron1 | T/G | 0.3464 | G | 26.84 | 24.33 | 22.10 |

| WT1 | rs5030141 | 11 | intron1 | A/C | 0.3369 | C | 31.71 | 28.84 | 27.70 |

| WT1 | rs5030317 | 11 | 3’-UTR | C/G | 0.1203 | G | 27.70 | 25.04 | 23.70 |

| WT1 | rs5030320 | 11 | 3’-UTR | G/A | 0.0826 | A | 27.70 | 24.96 | 23.20 |

HWE: Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium; MAF: minimal allele frequency;

goodness-of-fit chi-square test for HWE for genotype distribution in controls.

Chinese Han in Beijing, data from http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

Correlation between WT1 SNPs alleles and genotypes and risk of breast cancer

As shown in Table 4, individuals with the minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 showed a significant decrease of breast cancer risk in codominant model (OR = 0.6370, 95% CI: 0.4260-0.9520 for rs16754; OR = 0.5940, 95% CI: 0.3890-0.9070 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5870, 95% CI: 0.3850-0.8960 for 5030320, respectively) and recessive model (OR = 0.6420, 95% CI: 0.4340-0.9490 for rs16754; OR = 0.5990, 95% CI: 0.3960-0.9060 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5920, 95% CI: 0.3920-0.8950 for 5030320, respectively), compared with the corresponding controls.

Table 4.

Overall analyses of the associations between WT1 genotypes and breast cancer risk

| SNPs | Genetic model | Genotype | Controls (n = 749) | Cases (n = 709) | Adjusted ORa | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs16754 | Codominant | GG | 384 | 378 | reference | |

| GA | 293 | 285 | 0.9830 (0.7880-1.2260) | 0.8777 | ||

| AA | 72 | 46 | 0.6370 (0.4260-0.9520) | 0.0280 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 384 | 378 | reference | ||

| GA + AA | 365 | 331 | 0.9140 (0.7410-1.1270) | 0.3992 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 677 | 663 | reference | ||

| AA | 72 | 46 | 0.6420 (0.4340-0.9490) | 0.0261 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 1061 | 1041 | reference | ||

| A | 437 | 377 | 0.8720 (0.7390-1.0280) | 0.1034 | ||

| rs3930513 | Codominant | TT | 406 | 405 | reference | |

| TG | 284 | 263 | 0.9270 (0.7430-1.1570) | 0.5046 | ||

| GG | 59 | 41 | 0.6810 (0.4440-1.0450) | 0.0790 | ||

| Dominant | TT | 406 | 405 | reference | ||

| TG + GG | 343 | 304 | 0.8840 (0.7160-1.0920) | 0.2538 | ||

| Recessive | TT + TG | 690 | 668 | reference | ||

| GG | 59 | 41 | 0.7020 (0.4620-1.0680) | 0.0981 | ||

| Allele contrast | T | 1096 | 1073 | reference | ||

| G | 402 | 345 | 0.8710 (0.7340-1.0320) | 0.1098 | ||

| rs5030141 | Codominant | AA | 355 | 364 | reference | |

| AC | 313 | 281 | 0.8770 (0.7020-1.0950) | 0.2467 | ||

| CC | 81 | 64 | 0.7800 (0.5410-1.1250) | 0.1841 | ||

| Dominant | AA | 355 | 364 | reference | ||

| AC + CC | 394 | 345 | 0.8570 (0.6950-1.0570) | 0.1501 | ||

| Recessive | AA + AC | 668 | 645 | reference | ||

| CC | 81 | 64 | 0.8280 (0.5820-1.1770) | 0.2933 | ||

| Allele contrast | A | 1023 | 1009 | reference | ||

| C | 475 | 409 | 0.8770 (0.7460-1.0310) | 0.1116 | ||

| rs5030317 | Codominant | CC | 400 | 394 | reference | |

| CG | 283 | 275 | 0.9770 (0.7840-1.2190) | 0.8398 | ||

| GG | 66 | 40 | 0.5940 (0.3890-0.9070) | 0.0158 | ||

| Dominant | CC | 400 | 394 | reference | ||

| CG + GG | 349 | 315 | 0.9040 (0.7320-1.1150) | 0.3453 | ||

| Recessive | CC + CG | 683 | 669 | reference | ||

| GG | 66 | 40 | 0.5990 (0.3960-0.9060) | 0.0152 | ||

| Allele contrast | C | 1083 | 1063 | reference | ||

| G | 415 | 355 | 0.8590 (0.7260-1.0160) | 0.0758 | ||

| rs5030320 | Codominant | GG | 401 | 395 | reference | |

| GA | 281 | 274 | 0.9780 (0.7840-1.2210) | 0.8457 | ||

| AA | 67 | 40 | 0.5870 (0.3850-0.8960) | 0.0135 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 401 | 395 | reference | ||

| GA + AA | 348 | 314 | 0.9020 (0.7310-1.1130) | 0.3367 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 682 | 669 | reference | ||

| AA | 67 | 40 | 0.5920 (0.3920-0.8950) | 0.0129 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 1083 | 1064 | reference | ||

| A | 415 | 354 | 0.8550 (0.7230-1.0120) | 0.0688 |

adjusted by age (continuous variable) and menopausal status.

The same significant results were also found in the population with age equal or less than 50 years old under codominant model (OR = 0.5960, 95% CI: 0.3690-0.9620 for rs16754; OR = 0.5510, 95% CI: 0.3330-0.9120 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5440, 95% CI: 0.3290-0.8980 for 5030320, respectively) and recessive model (OR = 0.6110, 95% CI: 0.3840-0.9730 for rs16754; OR = 0.5660, 95% CI: 0.3460-0.9250 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5570, 95% CI: 0.3420-0.9090 for 5030320, respectively), compared with the corresponding controls (Table 5). However, no significant differences were demonstrated in the population older than 50 years.

Table 5.

Stratified analyses of the associations between WT1 genotypes and breast cancer risk by age of 50 years

| SNPs | Genetic model | Genotype | ≤ 50 years | > 50 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Controls (n = 556) | Cases (n = 460) | adjusted ORa | P | Controls (n = 193) | Cases (n = 249) | adjusted ORa | P | |||

| rs16754 | Codominant | GG | 283 | 249 | reference | 101 | 129 | reference | ||

| GA | 218 | 180 | 0.9430 (0.7240-1.2290) | 0.6652 | 75 | 105 | 1.1240 (0.7490-1.6890) | 0.5718 | ||

| AA | 55 | 31 | 0.5960 (0.3690-0.9620) | 0.0340 | 17 | 15 | 0.7960 (0.3710-1.7090) | 0.5584 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 283 | 249 | reference | 101 | 129 | reference | |||

| GA + AA | 273 | 211 | 0.8710 (0.6780-1.1200) | 0.2813 | 92 | 120 | 1.0670 (0.7230-1.5730) | 0.7450 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 501 | 429 | reference | 176 | 234 | reference | |||

| AA | 55 | 31 | 0.6110 (0.3840-0.9730) | 0.0378 | 17 | 15 | 0.7560 (0.3600-1.5880) | 0.4597 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 784 | 678 | reference | 277 | 363 | reference | |||

| A | 328 | 242 | 0.8370 (0.6860-1.0200) | 0.0778 | 109 | 135 | 0.9920 (0.7300-1.3480) | 0.9607 | ||

| rs3930513 | Codominant | TT | 301 | 266 | reference | 105 | 139 | reference | ||

| TG | 211 | 168 | 0.9060 (0.6950-1.1810) | 0.4660 | 73 | 95 | 1.0290 (0.6830-1.5490) | 0.8921 | ||

| GG | 44 | 26 | 0.6240 (0.3710-1.0500) | 0.0759 | 15 | 15 | 0.8810 (0.4030-1.9270) | 0.7512 | ||

| Dominant | TT | 301 | 266 | reference | 105 | 105 | reference | |||

| TG + GG | 255 | 194 | 0.8560 (0.6650-1.1020) | 0.2283 | 88 | 110 | 1.0050 (0.6800-1.4840) | 0.9811 | ||

| Recessive | TT + TG | 512 | 434 | reference | 178 | 234 | reference | |||

| GG | 44 | 26 | 0.6500 (0.3900 -1.0810) | 0.0967 | 15 | 15 | 0.8710 (0.4060-1.8690) | 0.7225 | ||

| Allele contrast | T | 813 | 700 | reference | 283 | 373 | reference | |||

| G | 299 | 220 | 0.8420 (0.6860-1.0320) | 0.0979 | 103 | 125 | 0.9800 (0.7170-1.3400) | 0.8994 | ||

| rs5030141 | Codominant | AA | 263 | 239 | reference | 92 | 125 | reference | ||

| AC | 232 | 178 | 0.8540 (0.6540-1.1140) | 0.2437 | 81 | 103 | 0.9870 (0.6550-1.4850) | 0.9483 | ||

| CC | 61 | 43 | 0.7690 (0.4990-1.1870) | 0.2359 | 20 | 21 | 0.8440 (0.4230-1.6840) | 0.6297 | ||

| Dominant | AA | 263 | 239 | reference | 92 | 125 | reference | |||

| AC + CC | 293 | 221 | 0.8360 (0.6510-1.0740) | 0.1615 | 101 | 124 | 0.9590 (0.6500-1.4140) | 0.8318 | ||

| Recessive | AA + AC | 495 | 417 | reference | 173 | 228 | reference | |||

| CC | 61 | 43 | 0.8260 (0.5440-1.2530) | 0.3684 | 20 | 21 | 0.8490 (0.4370-1.6500) | 0.6291 | ||

| Allele contrast | A | 758 | 656 | reference | 265 | 353 | reference | |||

| C | 354 | 264 | 0.8630 (0.7110-1.0470) | 0.1349 | 121 | 145 | 0.9440 (0.7010-1.2720) | 0.7044 | ||

| rs5030317 | Codominant | CC | 296 | 260 | reference | 104 | 134 | reference | ||

| CG | 209 | 173 | 0.9390 (0.7200-1.2240) | 0.6410 | 74 | 102 | 1.1150 (0.7430-1.6730) | 0.6000 | ||

| GG | 51 | 27 | 0.5510 (0.3330-0.9120) | 0.0204 | 15 | 13 | 0.7520 (0.3340-1.6900) | 0.4899 | ||

| Dominant | CC | 296 | 260 | reference | 104 | 134 | reference | |||

| CG + GG | 260 | 200 | 0.8600 (0.6690-1.1070) | 0.2428 | 89 | 115 | 1.0560 (0.7150-1.5580) | 0.7854 | ||

| Recessive | CC + CG | 505 | 433 | reference | 178 | 236 | reference | |||

| GG | 51 | 27 | 0.5660 (0.3460-0.9250) | 0.0231 | 15 | 13 | 0.7170 (0.3250-1.5830) | 0.4106 | ||

| Allele contrast | C | 801 | 693 | reference | 282 | 370 | reference | |||

| G | 311 | 227 | 0.8210 (0.6710-1.0050) | 0.0560 | 104 | 128 | 0.9830 (0.7200-1.3420) | 0.9148 | ||

| rs5030320 | Codominant | GG | 297 | 261 | reference | 104 | 134 | reference | ||

| GA | 207 | 172 | 0.9420 (0.7220-1.2280) | 0.6571 | 74 | 102 | 1.1150 (0.7430-1.6730) | 0.6000 | ||

| AA | 52 | 27 | 0.5440 (0.3290-0.8980) | 0.0173 | 15 | 13 | 0.7520 (0.3340-1.6900) | 0.4899 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 297 | 261 | reference | 104 | 134 | reference | |||

| GA + AA | 259 | 199 | 0.8600 (0.6680-1.1060) | 0.2397 | 89 | 115 | 1.0560 (0.7150-1.5580) | 0.7854 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 504 | 433 | reference | 178 | 236 | reference | |||

| AA | 52 | 27 | 0.5570 (0.3420-0.9090) | 0.0193 | 15 | 13 | 0.7170 (0.3250-1.5830) | 0.4106 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 801 | 694 | reference | 282 | 370 | reference | |||

| A | 311 | 226 | 0.8180 (0.6680-1.0010) | 0.0508 | 104 | 128 | 0.9830 (0.7200-1.3420) | 0.9148 | ||

adjusted by age (continuous variable) and menopausal status.

When stratified by menopausal status (Table 6), the significant association with decreased breast cancer risk was additionally identified in rs3930513, except for rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320, in pre-menopausal persons under codominant model (OR = 0.5400, 95% CI: 0.3290-0.8860 for rs16754; OR = 0.5350, 95% CI: 0.3120-0.9180 for rs3930513; OR = 0.5170, 95% CI: 0.3090-0.8660 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5080, 95% CI: 0.3040-0.8500 for rs5030320, respectively) and recessive model (OR = 0.5420, 95% CI: 0.3350-0.8780 for rs16754; OR = 0.5540, 95% CI: 0.3270-0.9400 for rs3930513; OR = 0.5080, 95% CI: 0.3040-0.8500 for rs5030317; OR = 0.5130, 95% CI: 0.3110-0.8480 for 5030320, respectively), compared with the corresponding controls. However, no significant differences were found in post-menopause group.

Table 6.

Stratified analyses of the associations between WT1 genotypes and breast cancer risk by menopausal status

| SNPs | Genetic model | Genotype | Pre-menopause | Post-menopause | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Controls (n = 519) | Cases (n = 447) | adjusted ORa | P | Controls (n =2 30) | Cases (n = 262) | adjusted ORa | P | |||

| rs16754 | Codominant | GG | 262 | 236 | reference | 122 | 142 | reference | ||

| GA | 203 | 182 | 0.9890 (0.7520-1.3010) | 0.9387 | 90 | 103 | 0.9750 (0.6710-1.4180) | 0.8955 | ||

| AA | 54 | 29 | 0.5400 (0.3290-0.8860) | 0.0148 | 18 | 17 | 0.8410 (0.4140-1.7100) | 0.6329 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 262 | 236 | reference | 122 | 142 | reference | |||

| GA + AA | 257 | 211 | 0.8900 (0.6860-1.1550) | 0.3817 | 108 | 120 | 0.9530 (0.6670-1.3630) | 0.7927 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 465 | 418 | reference | 212 | 245 | reference | |||

| AA | 54 | 29 | 0.5420 (0.3350-0.8780) | 0.0127 | 18 | 17 | 0.8500 (0.4260-1.6980) | 0.6456 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 727 | 654 | reference | 334 | 387 | reference | |||

| A | 311 | 240 | 0.8290 (0.6760-1.0170) | 0.0727 | 126 | 137 | 0.9440 (0.7100-1.2540) | 0.6903 | ||

| rs3930513 | Codominant | TT | 277 | 255 | reference | 129 | 150 | reference | ||

| TG | 198 | 168 | 0.9180 (0.6980-1.2080) | 0.5418 | 86 | 95 | 0.9470 (0.6500-1.3810) | 0.7782 | ||

| GG | 44 | 24 | 0.5350 (0.3120-0.9180) | 0.0232 | 15 | 17 | 1.0100 (0.4840-2.1120) | 0.9779 | ||

| Dominant | TT | 277 | 255 | reference | 129 | 150 | reference | |||

| TG + GG | 242 | 192 | 0.8450 (0.6510-1.0980) | 0.2082 | 101 | 112 | 0.9560 (0.6680-1.3700) | 0.8084 | ||

| Recessive | TT + TG | 475 | 423 | reference | 215 | 245 | reference | |||

| GG | 44 | 24 | 0.5540 (0.3270-0.9400) | 0.0284 | 15 | 17 | 1.0320 (0.5010-2.1250) | 0.9313 | ||

| Allele contrast | T | 752 | 678 | reference | 344 | 395 | reference | |||

| G | 286 | 216 | 0.8130 (0.6590-1.0040) | 0.0544 | 116 | 129 | 0.9760 (0.7300-1.3060) | 0.8717 | ||

| rs5030141 | Codominant | AA | 243 | 231 | reference | 112 | 133 | reference | ||

| AC | 216 | 176 | 0.8730 (0.6630-1.1500) | 0.3344 | 97 | 105 | 0.9010 (0.6190-1.3130) | 0.5886 | ||

| CC | 60 | 40 | 0.6920 (0.4410-1.0860) | 0.1096 | 21 | 24 | 0.9800 (0.5160-1.8610) | 0.9497 | ||

| Dominant | AA | 243 | 231 | reference | 112 | 133 | reference | |||

| AC + CC | 276 | 216 | 0.8330 (0.6420-1.0810) | 0.1689 | 118 | 129 | 0.9150 (0.6410-1.3070) | 0.6263 | ||

| Recessive | AA + AC | 459 | 407 | reference | 209 | 238 | reference | |||

| CC | 60 | 40 | 0.7360 (0.4770-1.1350) | 0.1653 | 21 | 24 | 1.0270 (0.5530-1.906) | 0.9337 | ||

| Allele contrast | A | 702 | 638 | reference | 321 | 371 | reference | |||

| C | 336 | 256 | 0.8400 (0.6880-1.0260) | 0.0881 | 139 | 153 | 0.9530 (0.7240-1.2560) | 0.7342 | ||

| rs5030317 | Codominant | CC | 275 | 247 | reference | 125 | 147 | reference | ||

| CG | 194 | 174 | 0.9830 (0.7470-1.2950) | 0.9056 | 89 | 101 | 0.9630 (0.6630-1.4000) | 0.8435 | ||

| GG | 50 | 26 | 0.5170 (0.3090-0.8660) | 0.0123 | 16 | 14 | 0.7570 (0.3540-1.6170) | 0.4717 | ||

| Dominant | CC | 275 | 247 | reference | 125 | 147 | reference | |||

| CG + GG | 244 | 200 | 0.8830 (0.6800-1.1470) | 0.3517 | 105 | 115 | 0.9320 (0.6510-1.3330) | 0.6991 | ||

| Recessive | CC + CG | 469 | 421 | reference | 214 | 248 | reference | |||

| GG | 50 | 26 | 0.5080 (0.3040-0.8500) | 0.0110 | 16 | 14 | 0.7680 (0.3650-1.6160) | 0.4876 | ||

| Allele contrast | C | 744 | 668 | reference | 339 | 395 | reference | |||

| G | 294 | 226 | 0.8220 (0.6670-1.0120) | 0.0645 | 121 | 129 | 0.9180 (0.6870-1.2250) | 0.5600 | ||

| rs5030320 | Codominant | GG | 275 | 248 | reference | 126 | 147 | reference | ||

| GA | 193 | 173 | 0.9760 (0.7410-1.2860) | 0.8644 | 88 | 101 | 0.9800 (0.6740-1.4240) | 0.9139 | ||

| AA | 51 | 26 | 0.5080 (0.3040-0.8500) | 0.0099 | 16 | 14 | 0.7620 (0.3570-1.6280) | 0.4829 | ||

| Dominant | GG | 275 | 248 | reference | 126 | 147 | reference | |||

| GA + AA | 244 | 199 | 0.8740 (0.6730-1.1350) | 0.3135 | 104 | 115 | 0.9460 (0.6610-1.3540) | 0.7628 | ||

| Recessive | GG + GA | 468 | 421 | reference | 214 | 248 | reference | |||

| AA | 51 | 26 | 0.5130 (0.3110-0.8480) | 0.0092 | 16 | 14 | 0.7680 (0.3650-1.6160) | 0.4876 | ||

| Allele contrast | G | 743 | 669 | reference | 340 | 395 | reference | |||

| A | 295 | 225 | 0.8130 (0.6600-1.0020) | 0.0520 | 120 | 129 | 0.9270 (0.6940-1.2380) | 0.6066 | ||

adjusted by age (continuous variable) and menopausal status.

Association between WT1 SNPs and genotypes and clinicopathological characteristics in breast cancer patients

WT1 SNPs genotypes under recessive model and their relations to clinical and pathological characteristics of breast cancer patients were shown in Table 7. Patients with homozygous minor allele of rs3930513 and rs5030141 were more likely to be ER negative (P = 0.0039 and 0.0049, respectively), while, carriers with that of rs16754 and rs5030141 tended to be PR negative (P = 0.0176 and 0.0085, respectively). No significant differences were found between patients with wild-type/heterozygous minor allele and the patients with homozygous minor allele of the five WT1 SNPs, with regard to age, menopausal status, T stage, N stage, M stage, TNM stage, HER-2 status and Ki-67 status (P > 0.05).

Table 7.

Associations between WT1 polymorphisms and the clinicopathological characteristics of breast cancer patients

| Parameter | rs16754 | rs3930513 | rs5030141 | rs5030317 | rs5030320 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| GG + CA (N=, %) | AA (N=, %) | P a | TT + TG (N=, %) | GG (N=, %) | P a | AA + AC (N=, %) | CC (N=, %) | P a | CC + CG (N=, %) | GG (N=, %) | P a | GG + GA (N=, %) | AA (N=, %) | P a | |

| Age | 0.7121 | 0.8395 | 0.6852 | 0.7208 | 0.7208 | ||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 429 (64.71) | 31 (67.39) | 434 (64.97) | 26 (63.41) | 417 (64.65) | 43 (67.19) | 433 (64.72) | 27 (67.50) | 433 (64.72) | 27 (67.50) | |||||

| > 50 | 234 (35.29) | 15 (32.61) | 234 (35.03) | 15 (36.59) | 228 (35.35) | 21 (32.81) | 236 (35.28) | 13 (32.50) | 236 (35.28) | 13 (32.50) | |||||

| Menopausal status | 0.9996 | 0.5377 | 0.9243 | 0.7922 | 0.7922 | ||||||||||

| pre-menopause | 418 (63.05) | 29 (63.04) | 423 (63.32) | 24 (58.54) | 407 (63.10) | 40 (62.50) | 421 (62.93) | 26 (65.00) | 421 (62.93) | 26 (65.00) | |||||

| post-menopause | 245 (36.95) | 17 (36.96) | 245 (36.68) | 17 (41.46) | 238 (36.90) | 24 (37.50) | 248 (37.07) | 14 (35.00) | 248 (37.07) | 14 (35.00) | |||||

| T stage | 0.0530b | 0.3201b | 0.6784b | 0.1075b | 0.1075b | ||||||||||

| T0 | 57 (8.6) | 0 (0.00) | 55 (8.32) | 24.88) | 53 (8.37) | 3 (4.69) | 57 (8.52) | 0 (0.00) | 57 (8.52) | 0 (0.00) | |||||

| T1 + T2 | 576 (86.88) | 45 (97.83) | 582 (87.13) | 39 (95.12) | 562 (87.13) | 59 (92.19) | 582 (87.00) | 39 (97.50) | 582 (87.00) | 39 (97.50) | |||||

| T3 + T4 | 30 (4.52) | 1 (2.17) | 31 (4.64) | 0 (0.00) | 29 (4.50) | 2 (3.13) | 30 (4.478) | 1 (2.50) | 30 (4.478) | 1 (2.50) | |||||

| N stage | 0.5247 | 0.4938 | 0.2945 | 0.5745 | 0.3709 | ||||||||||

| negative | 401 (60.48) | 30 (65.22) | 404 (60.48) | 27 (65.85) | 396 (61.40) | 35 (54.69) | 405 (60.54) | 26 (65.00) | 404 (60.39) | 30 (67.50) | |||||

| positive | 262 (39.52) | 16 (34.78) | 264 (39.52) | 14 (34.15) | 249 (38.60) | 29 (45.31) | 264 (39.46) | 14 (35.00) | 262 (39.61) | 16 (32.50) | |||||

| M stage | 0.7607b | 0.5111b | 0.6031b | 0.5080b | 0.5080b | ||||||||||

| M0 | 618 (93.21) | 44 (95.65) | 622 (93.11) | 40 (97.56) | 603 (93.49) | 59 (92.19) | 623 (93.12) | 39 (97.50) | 623 (93.12) | 39 (97.50) | |||||

| M1 | 45 (6.79) | 2 (4.35) | 46 (6.89) | 1 (2.44) | 42 (6.51) | 5 (7.81) | 46 (6.88) | 1 (2.50) | 46 (6.88) | 1 (2.50) | |||||

| TNM stage | 0.3589 | 0.252 | 0.4124 | 0.2925 | 0.2925 | ||||||||||

| I + II | 462 (69.68) | 35 (76.09) | 465 (69.61) | 32 (78.05) | 455 (70.54) | 42 (65.63) | 466 (69.66) | 31 (77.50) | 466 (69.66) | 31 (77.50) | |||||

| III + IV | 201 (30.32) | 11 (23.91) | 203 (30.39) | 9 (21.95) | 190 (29.46) | 22 (34.38) | 203 (30.34) | 9 (22.50) | 203 (30.34) | 9 (22.50) | |||||

| ER | 0.1064 | 0.0039 | 0.0049 | 0.3305 | 0.3305 | ||||||||||

| - | 222 (36.51) | 21 (48.84) | 220 (35.95) | 23 (58.97) | 211 (35.64) | 32 (54.24) | 226 (36.87) | 17 (44.74) | 226 (36.87) | 17 (44.74) | |||||

| + | 386 (63.49) | 22 (51.16) | 392 (64.05) | 16 (41.03) | 381 (64.36) | 27 (45.76) | 387 (63.13) | 21 (55.26) | 387 (63.13) | 21 (55.26) | |||||

| Unknown | 58 (8.18) | 58 (8.18) | 58 (8.18) | 58 (8.18) | 58 (8.18) | ||||||||||

| PR | 0.0176 | 0.0064 | 0.0085 | 0.1200 | 0.1200 | ||||||||||

| - | 254 (41.91) | 26 (60.47) | 255 (41.80) | 25 (64.10) | 245 (41.53) | 35 (59.32) | 259 (42.39) | 21 (55.26) | 259 (42.39) | 21 (55.26) | |||||

| + | 352 (58.09) | 17 (39.53) | 355 (58.20) | 14 (35.90) | 345 (58.47) | 24 (40.68) | 352 (57.61) | 17 (44.74) | 352 (57.61) | 17 (44.74) | |||||

| Unknown | 60 (8.46) | 60 (8.46) | 60 (8.46) | 60 (8.46) | 60 (8.46) | ||||||||||

| HER-2 | 0.7497 | 0.9134 | 0.5479 | ||||||||||||

| - | 420 (69.08) | 30 (71.43) | 422 (69.18) | 28 (70.00) | 405 (68.88) | 45 (72.58) | 423 (69.00) | 27 (72.97) | 0.6115 | 422 (68.84) | 28 (75.68) | 0.3818 | |||

| + | 188 (30.92) | 12 (28.57) | 188 (30.82) | 12 (30.00) | 183 (31.12) | 17 (27.42) | 190 (31.00) | 10 (27.03) | 191 (31.16) | 9 (24.32) | |||||

| Unknown | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | ||||||||||

| Ki-67 | 0.6965 | 0.5839 | 0.2225 | ||||||||||||

| - | 314 (51.90) | 22 (48.89) | 317 (51.97) | 19 (47.50) | 309 (52.46) | 27 (44.26) | 320 (52.37) | 16 (41.03) | 0.1692 | 321 (52.45) | 15 (39.47) | 0.1203 | |||

| + | 291 (48.10) | 23 (51.11) | 293 (48.03) | 21 (52.50) | 280 (47.54) | 34 (55.74) | 291 (47.63) | 23 (58.97) | 291 (47.55) | 23 (60.53) | |||||

| Unknown | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | 59 (8.32) | ||||||||||

Chi-square test;

fisher exact tests.

Correlation of WT1 mRNA expression levels with variant genotypes in CHB population

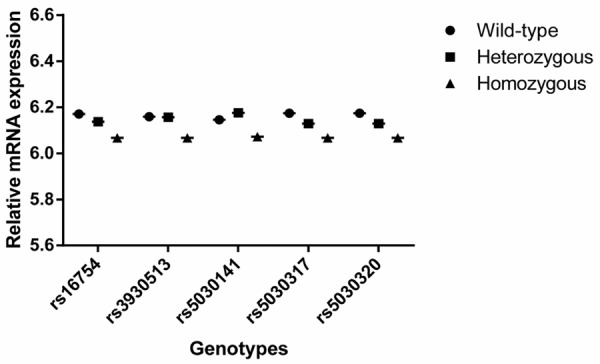

To explore possible underlying molecular mechanism, we performed genotype-phenotype correlation analysis using the available data on the WT1 genotypes and mRNA expression levels of lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from CHB population. According to the distributions of WT1 genotypes and mRNA expression level (Table 8), we found a significantly low level of WT1 mRNA expression for homozygous rare allele of WT1 gene, compared with wild-type and heterozygous group (P = 0.0021) as shown in Figure 1, which supports the finding of an association between WT1 SNPs and reduced breast cancer risk.

Table 8.

Distribution of WT1 variant genotypes and mRNA expression levels in Chinese Han Beijing population

| SNPs | Wild-type | Heterozygous | Homozygous | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| rs16754 | 23 | 6.1700 | 0.1751 | 19 | 6.1370 | 0.0100 | 3 | 6.0670 | 0.1340 |

| rs3930513 | 24 | 6.1590 | 0.1296 | 17 | 6.1560 | 0.1705 | 3 | 6.0670 | 0.1340 |

| rs5030141 | 22 | 6.1450 | 0.1253 | 18 | 6.1750 | 0.1702 | 5 | 6.0720 | 0.1219 |

| rs5030317 | 24 | 6.1740 | 0.1720 | 17 | 6.1290 | 0.1018 | 3 | 6.0670 | 0.1340 |

| rs5030320 | 24 | 6.1740 | 0.1720 | 17 | 6.1290 | 0.1018 | 3 | 6.0670 | 0.1340 |

Figure 1.

Effect of WT1 SNPs on mRNA expression in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from Chinese Han Beijing population.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the associations between breast cancer susceptibility and WT1 polymorphisms have not been detected in any population using case-control studies. Our results obtained from 709 breast cancer patients and 749 controls showed that minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 were associated with reduced risk of breast cancer, especially in participants with age equal or less than 50 years old or in pre-menopausal status, which indicated that WT1 SNPs could serve as a potential molecular marker for stratifying risk of breast cancer.

The WT1 gene, which encodes the protein consisting of four zinc finger domains at the C terminus and a glutamine and proline-rich domain at the N terminus [43], was recently found to play an oncogenic role in leukemogenesis and tumorigenesis, despite originally identified as a tumor suppressor gene [15,29,30,44]. As for breast cancer, accumulating evidences have demonstrated that wild-type WT1 gene plays an important role in the development and progression of breast cancer [45]. It was reported that WT1 could be detected in 87% of primary breast carcinomas, but not in normal breast epithelium [21]. In addition, prognostic studies showed that high WT1 mRNA level significantly correlated with worse outcomes of breast cancer [18,25], and WT1 could promote the proliferation and restrain the apoptosis of breast cancer cells [46-49], all indicating that WT1 might serve as an oncogene in breast cancer.

SNPs are the most frequent sequence variations in the human genome, accounting for much of the phenotypic diversity among individuals. SNPs may lead to a change of the encoded amino acids (nonsynonymous) or be silent (synonymous) [50]. They may influence promoter activity (gene expression), mRNA stability, and subcellular localization of mRNAs and/or proteins [51,52]. Evidences from population studies have shown that some SNPs can affect breast cancer risk [53-56]. A synonymous SNP of WT1 gene in exon 7, rs16754, consisting of a substitution of the nucleotide adenine with guanine at nucleotide position 1293 [57], has recently been considered as a prognostic factor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia [35,36,58] and renal cell carcinoma [37] in different populations. These findings may be due to the fact that rs16754 genotype variations could affect translation kinetics [35] and/or drug sensitivity [36], which indicated that WT1 SNPs might play certain roles in the biology of cancer; however, the potential impacts of WT1 SNPs in the development of breast cancer have not been uncovered.

To explore the correlation between WT1 SNPs and risk of breast cancer, we carried out the case-control study, and found that minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 were significantly associated with reduced risk of breast cancer. The protective effects of these SNPs were more evident in participants with age equal or less than 50 years old or in pre-menopausal status; the deceased susceptibility to breast cancer was also demonstrated for rs3930513 in pre-menopausal subjects. In addition, our results also showed that breast cancer patients with homozygous minor allele of rs16754, rs3930513 and rs5030141 were more likely to be ER and/or PR negative. All of these findings suggest that WT1 SNPs could be used as potentially promising biomarkers of individual genetic background to predict the risk of breast cancer, and support our hypothesis that WT1 SNPs may be involved in the initiation, development and even progression of breast cancer, although molecular mechanisms underlying this observed association still need to be clarified.

According data from the International HapMap Project [42], the G(C) allele frequency of rs16754 detected in our study was in concordance with that reported in the CHB population. Together with the results from another Chinese population [58] and Thai [59] and Korean [60] populations, it can be concluded that G(C) is the major allele in Asian population, while, A(T) is the major allele in Western populations, which could be attributed to the differences in ethnicities [37]. In rs16754, it is reported that the rare codon CGA (6.2 per thousand) is replaced by the more frequently used codon CGG (11.4 per thousand) [37], leading to increased translation kinetics that could potentially affect protein folding and thereby protein [35]. In fact, it has been proposed that synonymous SNPs may change protein amount, structure or function through alterations in RNA stability, folding, or splicing; differences in tRNA selection; or binding of noncoding RNAs [36]. Therefore, it is biologically plausible that rs16754 could take part in the regulation of WT1 expression, and thereby, affect the development of cancer, including breast cancer. The distributions of minor allele of other four SNPs are also in accordance with the data from HapMap in CHB population. As for the their putative functions as predicted by SNP Function prediction (http://snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov/snpinfo/snpfunc.htm) [61] and F-SNP database (http://compbio.cs.queensu.ca/F-SNP/) [62], rs3930513 and rs5030141 might be transcription factor binding sites, while, rs5030317 and rs5030320 might be miRNA (hsa-miR-600, hsa-miR-936) binding sites, indicating the potential involvements of these SNPs in transcriptional regulation of target genes.

To identify the potential mechanism, we conducted bioinformatics genotype- phenotype correlation analysis in CHB population, and found a relatively low level of WT1 mRNA expression for homozygous rare allele of WT1 gene, which could partially explain the association between WT1 SNPs and decreased risk of breast cancer since WT1 mRNA was shown to be over-expressed in breast cancer tissues and correlate with poor prognosis of breast cancer patients [18,19,21,25]. Nevertheless, additional molecular researches are needed to finally establish the links between WT1 genotypes and mRNA expression, because our preliminary results were only based on cell lines and bioinformatics analyses. In fact, even for rs16754, the most extendedly studied SNP of WT1, its impacts on WT1 mRNA expression [35-37] as well as targeted gene- and microRNA-expression patterns [63] have been largely unknown and inconsistent. Of course, the possibility that these SNPs may be in linkage disequilibrium with other untyped functional polymorphisms or susceptibility gene could not be excluded, which are ongoing to be identified by researchers.

In summary, our findings provide strong evidence linking minor alleles of rs16754, rs5030317 and rs5030320 to reduced risk of breast cancer, and the protective effects are more evident in the subjects with age equal or less than 50 years old or in pre-menopausal status. Therefore, WT1 SNPs could be used as a potential biomarker to predict the susceptibility to breast cancer of individuals. Large prospective and molecular epidemiological studies are needed to verify the observed relationship and clarify its underlying mechanism.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81102030), and Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunopathology, Ministry of Education of China (No. 2012JSZ101). Great gratitude were extended to Prof. Xiao Gao from Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, for kindly proof-reading, and Dr. Wen-Ting Tan from Institute of Infectious Diseases, Southwest Hospital, The Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China, for data interpretation.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

Authors have no relevant, potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:61. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, St Louis J, Finkelstein DM, Yu KD, Chen WQ, Shao ZM, Goss PE. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e279–e289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campeau PM, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz MD. Hereditary breast cancer: new genetic developments, new therapeutic avenues. Hum Genet. 2008;124:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou AC, Casadei S, Heikkinen T, Barrowdale D, Pylkas K, Roberts J, Lee A, Subramanian D, De Leeneer K, Fostira F, Tomiak E, Neuhausen SL, Teo ZL, Khan S, Aittomaki K, Moilanen JS, Turnbull C, Seal S, Mannermaa A, Kallioniemi A, Lindeman GJ, Buys SS, Andrulis IL, Radice P, Tondini C, Manoukian S, Toland AE, Miron P, Weitzel JN, Domchek SM, Poppe B, Claes KB, Yannoukakos D, Concannon P, Bernstein JL, James PA, Easton DF, Goldgar DE, Hopper JL, Rahman N, Peterlongo P, Nevanlinna H, King MC, Couch FJ, Southey MC, Winqvist R, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz M. Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:497–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colditz GA, Bohlke K. Priorities for the primary prevention of breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:186–194. doi: 10.3322/caac.21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell A, Anderson AS, Clarke RB, Duffy SW, Evans D, Garcia-Closas M, Gescher AJ, Key TJ, Saxton JM, Harvie MN. Risk determination and prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:446. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0446-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sueta A, Ito H, Kawase T, Hirose K, Hosono S, Yatabe Y, Tajima K, Tanaka H, Iwata H, Iwase H, Matsuo K. A genetic risk predictor for breast cancer using a combination of low-pen etrance polymorphisms in a Japanese population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:711–721. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1904-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Call KM, Glaser T, Ito CY, Buckler AJ, Pelletier J, Haber DA, Rose EA, Kral A, Yeger H, Lewis WH, et al. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms’ tumor locus. Cell. 1990;60:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90601-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haber DA, Buckler AJ, Glaser T, Call KM, Pelletier J, Sohn RL, Douglass EC, Housman DE. An internal deletion within an 11p13 zinc finger gene contributes to the development of Wilms’ tumor. Cell. 1990;61:1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90690-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gessler M, Poustka A, Cavenee W, Neve RL, Orkin SH, Bruns GA. Homozygous deletion in Wilms tumours of a zinc-finger gene identified by chromosome jumping. Nature. 1990;343:774–778. doi: 10.1038/343774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ariyaratana S, Loeb DM. The role of the Wilms tumour gene (WT1) in normal and malignant haematopoiesis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartkamp J, Roberts SG. The role of the Wilms’ tumour-suppressor protein WT1 in apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:629–631. doi: 10.1042/BST0360629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huff V. Wilms’ tumours: about tumour suppressor genes, an oncogene and a chameleon gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:111–121. doi: 10.1038/nrc3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chau YY, Hastie ND. The role of Wt1 in regulating mesenchyme in cancer, development, and tissue homeostasis. Trends Genet. 2012;28:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miwa H, Beran M, Saunders GF. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene (WT1) in human leukemias. Leukemia. 1992;6:405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyoshi Y, Ando A, Egawa C, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Tamaki H, Sugiyama H, Noguchi S. High expression of Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene predicts poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1167–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oji Y, Ogawa H, Tamaki H, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Kim EH, Soma T, Tatekawa T, Kawakami M, Asada M, Kishimoto T, Sugiyama H. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in solid tumors and its involvement in tumor cell growth. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1999;90:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menssen HD, Bertelmann E, Bartelt S, Schmidt RA, Pecher G, Schramm K, Thiel E. Wilms’ tumor gene (WT1) expression in lung cancer, colon cancer and glioblastoma cell lines compared to freshly isolated tumor specimens. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:226–232. doi: 10.1007/s004320050037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loeb DM, Evron E, Patel CB, Sharma PM, Niranjan B, Buluwela L, Weitzman SA, Korz D, Sukumar S. Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene (WT1) is expressed in primary breast tumors despite tumor-specific promoter methylation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:921–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakatsuka S, Oji Y, Horiuchi T, Kanda T, Kitagawa M, Takeuchi T, Kawano K, Kuwae Y, Yamauchi A, Okumura M, Kitamura Y, Oka Y, Kawase I, Sugiyama H, Aozasa K. Immunohistochemical detection of WT1 protein in a variety of cancer cells. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:804–814. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Boyd N, McKinney S, Mehl E, Palmer C, Leung S, Bowen NJ, Ionescu DN, Rajput A, Prentice LM, Miller D, Santos J, Swenerton K, Gilks CB, Huntsman D. Ovarian carcinoma subtypes are different diseases: implications for biomarker studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sera T, Hiasa Y, Mashiba T, Tokumoto Y, Hirooka M, Konishi I, Matsuura B, Michitaka K, Udaka K, Onji M. Wilms’ tumour 1 gene expression is increased in hepatocellular carcinoma and associated with poor prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi XW, Zhang F, Yang XH, Fan LJ, Zhang Y, Liang Y, Ren L, Zhong L, Chen QQ, Zhang KY, Zang WD, Wang LS, Jiang J. High Wilms’ tumor 1 mRNA expression correlates with basal-like and ERBB2 molecular subtypes and poor prognosis of breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1231–1236. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sotobori T, Ueda T, Oji Y, Naka N, Araki N, Myoui A, Sugiyama H, Yoshikawa H. Prognostic significance of Wilms tumor gene (WT1) mRNA expression in soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2006;106:2233–2240. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauscher J, Beschorner R, Gierke M, Bisdas S, Braun C, Ebner FH, Schittenhelm J. WT1 expression increases with malignancy and indicates unfavourable outcome in astrocytoma. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:556–561. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-202114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little M, Wells C. A clinical overview of WT1 gene mutations. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:209–225. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:3<209::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohenstein P, Hastie ND. The many facets of the Wilms’ tumour gene, WT1. Hum Mol Genet 2006. 15 Spec No 2:R196–201. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Han Y, Suarez Saiz F, Minden MD. A tumor suppressor and oncogene: the WT1 story. Leukemia. 2007;21:868–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King-Underwood L, Renshaw J, Pritchard-Jones K. Mutations in the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in leukemias. Blood. 1996;87:2171–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollink IH, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Zimmermann M, Balgobind BV, Arentsen-Peters ST, Alders M, Willasch A, Kaspers GJ, Trka J, Baruchel A, de Graaf SS, Creutzig U, Pieters R, Reinhardt D, Zwaan CM. Clinical relevance of Wilms tumor 1 gene mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:5951–5960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virappane P, Gale R, Hills R, Kakkas I, Summers K, Stevens J, Allen C, Green C, Quentmeier H, Drexler H, Burnett A, Linch D, Bonnet D, Lister TA, Fitzgibbon J. Mutation of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene is a poor prognostic factor associated with chemotherapy resistance in normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia: the United Kingdom Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5429–5435. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Mrozek K, Maharry K, Langer C, Baldus CD, Zhao W, Powell BL, Baer MR, Carroll AJ, Caligiuri MA, Kolitz JE, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD. Wilms’ tumor 1 gene mutations independently predict poor outcome in adults with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a cancer and leukemia group B study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4595–4602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho PA, Kuhn J, Gerbing RB, Pollard JA, Zeng R, Miller KL, Heerema NA, Raimondi SC, Hirsch BA, Franklin JL, Lange B, Gamis AS, Alonzo TA, Meshinchi S. WT1 synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism rs16754 correlates with higher mRNA expression and predicts significantly improved outcome in favorable-risk pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:704–711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damm F, Heuser M, Morgan M, Yun H, Grosshennig A, Gohring G, Schlegelberger B, Dohner K, Ottmann O, Lubbert M, Heit W, Kanz L, Schlimok G, Raghavachar A, Fiedler W, Kirchner H, Dohner H, Heil G, Ganser A, Krauter J. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the mutational hotspot of WT1 predicts a favorable outcome in patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:578–585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bao WG, Zhang X, Zhang JG, Zhou WJ, Bi TN, Wang JC, Yan WH, Lin A. Biobanking of fresh-frozen human colon tissues: impact of tissue ex-vivo ischemia times and storage periods on RNA quality. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1737–1744. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu QY, Yu JT, Miao D, Ma XY, Wang HF, Wang W, Tan L. An exploratory study on STX6, MOBP, MAPT, and EIF2AK3 and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1519, e1513–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng F, Deng YP, Yi X, Cao HY, Zou HQ, Wang X, Liang CR, Wang YR, Zhang LL, Gao CY, Xu ZQ, Lian Y, Wang L, Zhou XF, Zhou HD, Wang YJ. No association of SORT1 gene polymorphism with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease in the Chinese Han population. Neuroreport. 2013;24:464–468. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283619f43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu ML, He J, Wang M, Sun MH, Jin L, Wang X, Yang YJ, Wang JC, Zheng L, Xiang JQ, Wei QY. Potentially functional polymorphisms in the ERCC2 gene and risk of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Chinese populations. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6281. doi: 10.1038/srep06281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holm K, Melum E, Franke A, Karlsen TH. SNPexp - A web tool for calculating and visualizing correlation between HapMap genotypes and gene expression levels. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:600. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.International HapMap 3 Consortium. Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Schaffner SF, Yu F, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Bonnen PE, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, de Bakker PI, Deloukas P, Gabriel SB, Gwilliam R, Hunt S, Inouye M, Jia X, Palotie A, Parkin M, Whittaker P, Yu F, Chang K, Hawes A, Lewis LR, Ren Y, Wheeler D, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Barnes C, Darvishi K, Hurles M, Korn JM, Kristiansson K, Lee C, McCarrol SA, Nemesh J, Dermitzakis E, Keinan A, Montgomery SB, Pollack S, Price AL, Soranzo N, Bonnen PE, Gibbs RA, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Keinan A, Price AL, Yu F, Anttila V, Brodeur W, Daly MJ, Leslie S, McVean G, Moutsianas L, Nguyen H, Schaffner SF, Zhang Q, Ghori MJ, McGinnis R, McLaren W, Pollack S, Price AL, Schaffner SF, Takeuchi F, Grossman SR, Shlyakhter I, Hostetter EB, Sabeti PC, Adebamowo CA, Foster MW, Gordon DR, Licinio J, Manca MC, Marshall PA, Matsuda I, Ngare D, Wang VO, Reddy D, Rotimi CN, Royal CD, Sharp RR, Zeng C, Brooks LD, McEwen JE. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoll R, Lee BM, Debler EW, Laity JH, Wilson IA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structure of the Wilms tumor suppressor protein zinc finger domain bound to DNA. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1227–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugiyama H. WT1 (Wilms’ tumor gene 1): biology and cancer immunotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:377–387. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oji Y, Miyoshi Y, Kiyotoh E, Koga S, Nakano Y, Ando A, Hosen N, Tsuboi A, Kawakami M, Ikegame K, Oka Y, Ogawa H, Noguchi S, Sugiyama H. Absence of mutations in the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in primary breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:74–77. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zapata-Benavides P, Tuna M, Lopez-Berestein G, Tari AM. Downregulation of Wilms’ tumor 1 protein inhibits breast cancer proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;295:784–790. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuna M, Chavez-Reyes A, Tari AM. HER2/neu increases the expression of Wilms’ Tumor 1 (WT1) protein to stimulate S-phase proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:1648–1652. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caldon CE, Lee CS, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Wilms’ tumor protein 1: an early target of progestin regulation in T-47D breast cancer cells that modulates proliferation and differentiation. Oncogene. 2008;27:126–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keating GL, Reid HM, Eivers SB, Mulvaney EP, Kinsella BT. Transcriptional regulation of the human thromboxane A2 receptor gene by Wilms’ tumor (WT)1 and hypermethylated in cancer (HIC) 1 in prostate and breast cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:476–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen R, Davydov EV, Sirota M, Butte AJ. Non-Synonymous and Synonymous Coding SNPs Show Similar Likelihood and Effect Size of Human Disease Association. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shastry B. SNPs: Impact on Gene Function and Phenotype. In: Komar AA, editor. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Humana Press; 2009. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt R, Sauna ZE, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Silent (synonymous) SNPs: should we care about them? Methods Mol Biol. 2009;578:23–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-411-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ripperger T, Gadzicki D, Meindl A, Schlegelberger B. Breast cancer susceptibility: current knowledge and implications for genetic counselling. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:722–731. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mavaddat N, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Garcia-Closas M. Genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Molecular Oncology. 2010;4:174–191. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahdi KM, Nassiri MR, Nasiri K. Hereditary genes and SNPs associated with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:3403–3409. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, Schmidt MK, Chang-Claude J, Bojesen SE, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Dicks E, Lee A, Turnbull C, Rahman N Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Collaboration; Fletcher O, Peto J, Gibson L, Dos Santos Silva I, Nevanlinna H, Muranen TA, Aittomäki K, Blomqvist C, Czene K, Irwanto A, Liu J, Waisfisz Q, Meijers-Heijboer H, Adank M Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON); van der Luijt RB, Hein R, Dahmen N, Beckman L, Meindl A, Schmutzler RK, Müller-Myhsok B, Lichtner P, Hopper JL, Southey MC, Makalic E, Schmidt DF, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ, Vincent D, Bacot F, Tessier DC, Canisius S, Wessels LF, Haiman CA, Shah M, Luben R, Brown J, Luccarini C, Schoof N, Humphreys K, Li J, Nordestgaard BG, Nielsen SF, Flyger H, Couch FJ, Wang X, Vachon C, Stevens KN, Lambrechts D, Moisse M, Paridaens R, Christiaens MR, Rudolph A, Nickels S, Flesch-Janys D, Johnson N, Aitken Z, Aaltonen K, Heikkinen T, Broeks A, Veer LJ, van der Schoot CE, Guénel P, Truong T, Laurent-Puig P, Menegaux F, Marme F, Schneeweiss A, Sohn C, Burwinkel B, Zamora MP, Perez JI, Pita G, Alonso MR, Cox A, Brock IW, Cross SS, Reed MW, Sawyer EJ, Tomlinson I, Kerin MJ, Miller N, Henderson BE, Schumacher F, Le Marchand L, Andrulis IL, Knight JA, Glendon G, Mulligan AM kConFab Investigators; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group; Lindblom A, Margolin S, Hooning MJ, Hollestelle A, van den Ouweland AM, Jager A, Bui QM, Stone J, Dite GS, Apicella C, Tsimiklis H, Giles GG, Severi G, Baglietto L, Fasching PA, Haeberle L, Ekici AB, Beckmann MW, Brenner H, Müller H, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Swerdlow A, Ashworth A, Orr N, Jones M, Figueroa J, Lissowska J, Brinton L, Goldberg MS, Labrèche F, Dumont M, Winqvist R, Pylkäs K, Jukkola-Vuorinen A, Grip M, Brauch H, Hamann U, Brüning T GENICA (Gene Environment Interaction and Breast Cancer in Germany) Network. Radice P, Peterlongo P, Manoukian S, Bonanni B, Devilee P, Tollenaar RA, Seynaeve C, van Asperen CJ, Jakubowska A, Lubinski J, Jaworska K, Durda K, Mannermaa A, Kataja V, Kosma VM, Hartikainen JM, Bogdanova NV, Antonenkova NN, Dörk T, Kristensen VN, Anton-Culver H, Slager S, Toland AE, Edge S, Fostira F, Kang D, Yoo KY, Noh DY, Matsuo K, Ito H, Iwata H, Sueta A, Wu AH, Tseng CC, Van Den Berg D, Stram DO, Shu XO, Lu W, Gao YT, Cai H, Teo SH, Yip CH, Phuah SY, Cornes BK, Hartman M, Miao H, Lim WY, Sng JH, Muir K, Lophatananon A, Stewart-Brown S, Siriwanarangsan P, Shen CY, Hsiung CN, Wu PE, Ding SL, Sangrajrang S, Gaborieau V, Brennan P, McKay J, Blot WJ, Signorello LB, Cai Q, Zheng W, Deming-Halverson S, Shrubsole M, Long J, Simard J, Garcia-Closas M, Pharoah PD, Chenevix-Trench G, Dunning AM, Benitez J, Easton DF. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45:353–361. 361e1–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaur GC, Ramadan SM, Cicconi L, Noguera NI, Luna I, Such E, Lavorgna S, Di Giandomenico J, Sanz MA, Lo-Coco F. Analysis of mutational status, SNP rs16754, and expression levels of Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1855–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen X, Yang Y, Huang Y, Tan J, Chen Y, Yang J, Dou H, Zou L, Yu J, Bao L. WT1 mutations and single nucleotide polymorphism rs16754 analysis of patients with pediatric acute myeloid leukemia in a Chinese population. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:2195–2204. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.685732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lauhakirti D, Sritana N, Boonthimat C, Promsuwicha O, Auewarakul CU. WT1 mutations and polymorphisms in Southeast Asian acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91:682–686. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi Y, Lee JH, Hur EH, Kang MJ, Kim SD, Lee JH, Kim DY, Lim SN, Bae KS, Lim HS, Seol M, Kang YA, Lee KH. Single nucleotide polymorphism of Wilms’ tumor 1 gene rs16754 in Korean patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Z, Taylor JA. SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W600–605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee PH, Shatkay H. F-SNP: computationally predicted functional SNPs for disease association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D820–824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Metzeler KH, Whitman SP, Schwind S, Kohlschmidt J, Wu YZ, Powell BL, Carter TH, Kolitz JE, Wetzler M, Carroll AJ, Baer MR, Moore JO, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD. Clinical outcome and gene- and microRNA-expression profiling according to the Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) single nucleotide polymorphism rs16754 in adult de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Haematologica. 2011;96:1488–1495. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.041905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]