Abstract

Background

Toxoplasmosis is a worldwide zoonosis. The objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence and assess the potential risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infections in animals and humans in Ethiopia by using meta-analytical methods.

Methods

Published studies on T. gondii in animals and humans in Ethiopia were searched in Medline, Google Scholar and the lists of references of articles. Eligible studies were selected by using inclusion and exclusion criteria. The risks of within and across study biases, and the variations in prevalence estimates attributable to heterogeneities were assessed. Pooled prevalence was estimated by the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model.

Results

Thirty two studies were eligible and data from 5689 animals and 5718 humans were used for quantitative syntheses. The pooled IgG seroprevalence in cats, small ruminants and humans were estimated at 87.72 % (95 % CI = 78.63, 93.28), 34.59 % (95 % CI = 21.08, 51.12) and 74.73 % (95 % CI = 61.85, 84.36), respectively. The odds of infections were higher in pregnant than in non pregnant women (OR = 3.96), in individuals that had contact with cats than those with no contact (OR = 2.53), and in urban than in rural inhabitants (OR = 2.06).

Conclusions

Toxoplasmosis is highly prevalent and could be a cause of considerable reproductive wastage in small ruminants and multiple diseases in humans in Ethiopia. Public education on preventive measures could help reduce the transmission of the parasite to humans.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0901-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Animals, Ethiopia, Humans, Prevalence, Toxoplasma gondii

Background

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread zoonotic parasite that infects all warm-blooded animals and humans [1]. Felids are its definitive hosts and excrete oocysts in their feces [2, 3], and the oocyst burden in areas where cats selectively defecate is high [4]. Animals and humans acquire infections mainly by ingesting food or water contaminated with sporulated oocysts and tissue cysts [5]. Although most infections are asymptomatic, reproductive losses in animals [6] and multiple disorders, that include cognitive impairment and fatal encephalitis in humans could come about [7, 8]. Additionally, there are reports of associations between T. gondii infections with schizophrenia [9, 10], bipolar disorder [11, 12], suicide [13], epilepsy [14] and traffic accidents [15, 16].

Despite T.gondii being an important zoonotic pathogen, there is no national survey that addressed the multiple disorders it causes in humans, its impact in animal production, its temporal and spatial distribution and the risk factors associated with the occurrence of the disease in Ethiopia. The objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of T. gondii infection in cats, food animals and humans in Ethiopia, and assess the potential risk factors of infection.

Methods

The study was conducted according to the PRISMA guideline (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [17]. The PRISMA checklist was used to ensure inclusion of relevant information in the analysis (see Additional file 1).

Literature search

Published studies were searched in Medline. Non-Medline indexed articles were searched in Google Scholar and the lists of references of articles. Toxoplasm* and Ethiopia were the main MeSH terms used in electronic searches. Additional searches were done by using the main MeSH terms, Boolean operators, prevalence, incidence, cats, cattle, sheep, goats, camels, pigs, chicken and humans. The last search was done on December 23, 2014. Full text articles were downloaded or obtained from the library of the school of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, and from Dr. Jitender P. Dubey.

Selection of studies

A study was eligible for quantitative analyses if (i) it was published in English, (ii) it was cross-sectional, (iii) the methods were coprological and/or serological [Sabin Feldman dye test (SFT), modified agglutination test (MAT), modified direct agglutination test (MDAT), direct agglutination test (DAT), enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and latex agglutination test (LAT)], and (iv) the sample size was greater than 35. Studies were excluded if the titles and abstracts were not relevant to the outcomes of interest or did not fulfill the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction

From each eligible study, the following data were extracted: the first author, year of publication, year of study, location, climatic zone, altitude, study design, sample size, species, sex, age group, test methods and the number of positive samples. In addition, from studies on humans, the following were extracted: setting (hospital/non-hospital), pregnancy status (pregnant/non pregnant), HIV status (HIV positive/HIV negative), residence (urban/rural), behavior (apparently normal/abnormal), raw meat (consumer/non consumer), raw vegetable (consumer/non consumer), presence of cats in the household/contact (yes/no) and water source (pipe/others).

Data analysis

Data on cats, food animals and humans were analyzed separately. The study level estimates were transformed to logit event estimates [18, 19] by the following formula: lp = ln [p/ (1 − p)], where lp = logit event estimate; ln = natural logarithm; p = study level estimate. The variances of the estimates were calculated by the following formula: v (lp) = 1/(np) + 1/ [n (1 − p)], where v = variance and n = sample size.

Bias and heterogeneity analyses

The qualities of the study methods (study design and serological tests) were used to assess the within study biases. The across study bias (small study effects) was examined by funnel plots, and the statistical significance was assessed by the Egger’s regression asymmetry test [20]. The Duval and Tweedie non-parametric ‘fill and trim’ linear random method was used to calculate unbiased estimates [21]. The heterogeneities of study level estimates were assessed by Galbraith plot [22] and Cochran’s Q test. A non significant heterogeneity was accepted if the ratio of Q and the degree of freedom (Q/df) was less than one. The percentage of the variation in prevalence estimates attributable to heterogeneity was quantified by the inverse variance index (I2), and I2 values of 25 %, 50 % and 75 % were considered as low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively [23]. Subgroup analyses were done if the heterogeneities were moderate to high. A study was included in a subgroup analysis if the number of individuals (n) was more than 25 % of the mean of the subgroup.

Pooling and sensitivity tests

The DerSimonian and Laird random effects model was used to pool logit event estimates [24]. Pooled logit estimates were transformed to prevalence estimates (p) by the following formula: p = elp/ (elp + 1): where e = the base of natural logarithm. Single study omitted influence analyses were done to test the robustness of a pooled estimate, and a study was considered to have no influence if the pooled estimate without it was within the 95 % confidence limits of the overall mean. The Z test was used to test whether a pooled estimate significantly differs from zero or not. The Yates corrected Chi Square test was used to test the significance of a difference between estimates [25, 26]. Alpha was set at 0.05.

Microsoft Office Excel 2007 was used to transform study level estimates to logit event estimates, and to back transform pooled logit event estimates to prevalence estimates. Epi infoTM (Version 3.5.1, Center for Disease Control, CDC, USA) was used to compare groups. Stata (Version 11.1, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) was used in all other analyses.

Results

Search results and eligible studies

Figure 1 shows the search results. A total of 63 studies were found of which 18 were excluded based on the titles and abstracts. Of the studies screened for eligibility, 12 were excluded due to the following reasons: one was not available; two were abstracts; the sample size was 20 in one; the data was inconsistent in one; the diagnosis was established on the basis of clinical signs in one; IHAT was used in three, and the methods were not described in three studies. A total of 32 full-text studies were used for quantitative analyses [27–58].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the selection of eligible studies

Characteristics of the eligible studies

On the whole, data from 5689 animals (124 cats, 1950 sheep, 2102 goats, 726 chickens, 402 pigs and 385 camels) and 5718 humans from several regions of Ethiopia were analyzed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the eligible studies

| Author | Year of study | Location | Host | Method | Number | Positive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zewdu et al. [27] | 2010–2011 | CE | Goat | ELISA | 927 | 183 (19.74) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [28] | 2010–2011 | CE | Sheep | ELISA | 1030 | 357 (34.66) |

| Teshale [29] | 2005–2006 | CSE | Sheep, goat | MDAT | 641 | 480 (74.88) |

| Demissie and Tilahun [30] | 2000–2001 | CE | Sheep, goat | MDAT | 468 | 159 (33.97) |

| Negash et al. [31] | 1999–2000 | CE | Sheep, goat | MDAT/ELISA | 174 | 75 (43.10) |

| Gebremedhin and Gizaw [32] | 2013–2014 | SE | Sheep, goat | ELISA | 184 | 48 (26.09) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [33] | 2011–2012 | CE | Sheep, goat | DAT | 628 | 111 (17.68) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [34] | 2012–2013 | CE | Camel | MAT | 385 | 187 (48.57) |

| Tilahun et al. [35] | 2012 | CE | Chicken | MAT | 125 | 48 (38.40) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [36] | 2012–2013 | CE | Chicken | MAT | 601 | 183 (30.45) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [37] | 2014 | CE | Pig | DAT | 402 | 129 (32.09) |

| Dubey [38] | 2011 | CE | Cat | MAT | 36 | 33 (91.67) |

| Tiao [39] | 2012 | CE | Cat | MAT | 48 | 41 (85.42) |

| Negash et al. [31] | 1999–2000 | CE | Cat | Coprology | 40 | 5 (12.5) |

| Dubey [38] | 2011 | CE | Cat | Coprology | 36 | 8 (22.22) |

| Mellbin and Vahlquist [40] | nr | WCSE | human | SFT | 267 | 102 (38.20) |

| De Roever–Bonnet [41] | nr | CE | human | SFT | 99 | 47 (47.47) |

| Guebre Xabier et al. [42] | 1990 | CSE | human | ELISA | 919 | 673 (73.23) |

| Eshete et al. [43] | nr | CE | human | ELISA | 94 | 19 (20.21) |

| Woldemichael et al.[44] | 1995–1996 | CE | human | SFT/LAT | 340 | 268 (78.82) |

| Negash et al. [45] | 1999–2000 | CE | human | MDAT | 65 | 39 (60.00) |

| Yimer et al. [46] | nr | CE | human | ELISA | 279 | 270 (96.77) |

| Shibre et al. [47]a | 2005 | CE | human | ELISA | 90 | 80 (88.89) |

| Shimelis et al. [48] | 2007 | CE | human | ELISA | 330 | 297 (90.00) |

| Tedla et al. [49]a | 2009 | CE | human | ELISA | 456 | 434 (95.18) |

| Zemene et al. [50] | 2011 | SE | human | ELISA | 201 | 163 (81.09) |

| Gebremedhin et al. [51] | 2010–2011 | CE | human | ELISA | 425 | 346 (81.41) |

| Aleme et al. [52] | 2011–2012 | CE | human | ELISA | 150 | 141 (94.00) |

| Walle et al. [53] | nr | NE | human | ELISA | 204 | 161 (78.92) |

| Muluye et al. [54] | 2012–2013 | NE | human | LAT | 170 | 130 (76.47) |

| Tadesse et al. [55] | 2012 | NE | human | LAT | 422 | 171 (40.52) |

| Endris et al. [56] | 2010–2011 | NE | human | LAT | 385 | 341 (88.57) |

| Zeweld et al. [57] | 2012–2013 | NE | human | ELISA | 651 | 51 (7.83) |

| Yohannes et al. [58] | 2013 | SE | human | ELISA | 170 | 150 (88.24) |

CE, Central Ethiopia; CSE, Central and Southern Ethiopia; DAT, direct agglutination test; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LA, latex agglutination test; MAT, modified agglutination test; MDAT, modified direct agglutination test; MDAT/ELISA, modified direct agglutination test and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; n, sample size; NE, Northern Ethiopia; nr, not reported; SE, Southern Ethiopia; SFT, Sabin-Feldman dye test; WCSE, Western, Central and Southern Ethiopia

aData on T.gondii infection was collected before the trials

Bias and heterogeneity assessment

All studies on animals were cross-sectional, and the serological tests were ELISA, DAT, MDAT and MAT. All studies on humans were cross-sectional and IgG seroprevalence was examined by using ELISA, LAT, SFDT and MDAT. According to the manufacturers of the kits, the sensitivities and specificities of the tests were > = 92 %, and > = 95 %, respectively. As the sensitivity and specificity of LAT was lower than those of the other tests, a subgroup analysis of the estimates of human studies that used LAT vs. other tests did not yield a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). The funnel plots (Fig. 2) and the bias coefficients in both food animal [b = 0.54 (95 % CI = −19.27, 20.35; p > 0.05), and human [b = 5.45 (95 % CI = −4.67, 15.57; p > 0.05) studies did not suggest the presence of bias, and no theoretical missing study was incorporated by the Duval and Tweedie non-parametric method. The percentages of the variations in prevalence estimates attributable to heterogeneities were zero, 97.6 % and 98.6 % in cat, food animal and human studies, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Funnel plots of the logit IgG seroprevalence estimates (lp) in food animals (a) and humans (b)

Pooled prevalence estimates

Cats

The pooled prevalence of seropositive cats was 87.72 % (95 % CI = 78.63, 93.28; p < 001), I2 = 0. The pooled prevalence of oocyst shedder cats was 17.51 % (95 % CI = 9.77, 29.36; p < 001), I2 = 19 %.

Food animals

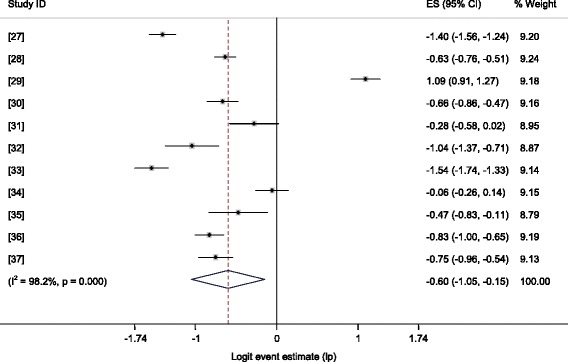

Figure 3 shows a forest plot of the IgG logit event estimates in food animals. The pooled estimates by potential risk factors are presented in Table 2. The overall prevalence of T. gondii infection was 35.5 % (95 % CI = 25.96, 46.36), and the estimates for ruminants and non-ruminants did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). In subgroup analyses, the pooled seroprevalence of T. gondii in small ruminants was 34.59 % (95 % CI = 21.08, 51.12; p > 0.05), I2 = 98.9 %, with a higher occurrence in sheep than in goats, in females than in males, and in adults than in young animals. All single study omitted estimates lie within the 95 % confidence intervals of the respective overall means of each group.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the logit IgG seroprevalence estimates (lp) in food animals

Table 2.

Pooled estimates of T. gondii in food animals by potential risk factors

| Risk factors | p (95 % CI) | Z-p | Q/df | Q-p | I2 | X 2 | Y-p | OR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All animals | Overall | 35.50 (25.96,46.36) | 0.009 | 56.97 | 0.000 | 98.2 | |||

| Ruminant | 32.54 (22.51,44.47) | 0.005 | 32.41 | 0.000 | 98.1 | 0.01 | 0.933 | 1.01 (0.87,1.16) | |

| Non-ruminant | 32.34 (28.88,35.99) | 0.000 | 1.5 | 0.223 | 33.4 | ||||

| Small Ruminants | Overall | 34.59 (21.08, 51.12) | 0.067 | 88.69 | 0.000 | 98.9 | |||

| Sheep | 33.51 (26.06, 41.90) | 0.000 | 10.71 | 0.000 | 90.7 | 10.24 | 0.001 | 1.25 (1.09,1.43) | |

| Goat | 28.80 (11.17, 56.54) | 0.129 | 100.39 | 0.000 | 99 | ||||

| Female | 29.38 (23.06, 36.63) | 0.000 | 9.73 | 0.000 | 89.7 | 23.95 | 0.000 | 1.70 (1.37,2.12) | |

| Male | 19.67 (10.80, 33.09) | 0.000 | 11.48 | 0.000 | 91.3 | ||||

| Adult | 34.30 (24.96, 45.07) | 0.005 | 18.79 | 0.000 | 94.7 | 100.50 | 0.000 | 3.06 (2.43,3.86) | |

| Young | 14.62 (10.93, 19.26) | 0.000 | 2.35 | 0.070 | 57.4 | ||||

| Midland a | 53.32 (36.12, 69.76) | 0.710 | 16.09 | 0.000 | 93.8 | 45.43 | 0.000 | 2.27 (1.78,2.91) | |

| Highland | 33.45. (29.78, 37.36) | 0.000 | 0.28 | 0.597 | 0 | ||||

| Lowland | 14.99 (8.0, 26.39) | 0.000 | . | ||||||

I2, inverse variance index; OR, odds ratio; Q, Cochran’s X 2; Y-p, probability of Yates test; Z-p, probability of Z test

aThe comparison was between midland and highland estimates

Humans

Figure 4 shows a forest plot of the logit estimates in humans. The pooled prevalence estimates by potential risk factors are presented in Table 3. The overall pooled prevalence was 74.73 % (95 % CI = 61.85, 84.36). The pooled estimate was affected by sex, age, pregnancy, status, cat contact/ possession and residential area but not by raw meat and raw vegetable consumption habits, and source of water. The pooled seroprevalence in patients with behavioral disorders (schizophrenia/bipolar disorder) was 93.88 % (95 % CI = 81.47, 98.16; p < 001), I2 = 88.2 %. All single study omitted estimates lie within the 95 % confidence intervals of the respective overall means of each group.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the logit IgG seroprevalence estimates (lp) in humans

Table 3.

Pooled estimates of T. gondii in humans by potential risk factors

| Risk factors | p (95 % CI) | Z-p | Q/df | Q-p | I2 | X 2 | Y-p | OR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 74.73 (61.85,84.36) | 0.000 | 70.4 | 0.000 | 98.6 | ||||

| Sex | Male | 73.54 (41.95, 91.44) | 0.137 | 51.1 | 0.000 | 98 | 37.17 | 0.000 | 1.65 (1.40,1..95) |

| Female | 62.74 (40.08,80.91) | 0.269 | 69.4 | 0.000 | 98.6 | ||||

| Age | Adults | 69.87 (47.50,85.59) | 0.080 | 80.2 | 0.000 | 98.8 | 51.06 | 0.000 | 1.95 (1.62,2.36) |

| Children | 54.34 (24.81,81.11) | 0.790 | 54.8 | 0.000 | 98.2 | ||||

| Pregnancy | Pregnant | 62.55 (29.88, 86.74) | 0.462 | 56.8 | 0.000 | 98.2 | 152.83 | 0.000 | 3.96 (3.15,4.97) |

| Non-pregnant | 29.59 (0.75, 95.87) | 0.672 | 197.8 | 0.000 | 99.5 | ||||

| Cat | Contact | 85.96 (74.12, 92.90) | 0.000 | 13.6 | 0.000 | 92.6 | 64.10 | 0.000 | 2.53 (2.00,3.20) |

| No contact | 70.70 (53.74, 83.37) | 0.018 | 27.4 | 0.000 | 96.4 | ||||

| Residence | Urban | 82.58 (73.63, 88.93) | 0.000 | 2.7 | 0.000 | 96.3 | 64.04 | 0.000 | 2.06 (1.71,2.47) |

| Rural | 69.80 (52.40, 82.91) | 0.027 | 19.8 | 0.000 | 94.9 | ||||

| Meat | Raw Ca | 77.22 (63.85, 86.68) | 0.000 | 18.3 | 0.000 | 94.5 | 0.65 | 0.421 | 1.10 (0.88,1.36) |

| Raw NCb | 75.58 (51.22.90.11) | 0.040 | 36.0 | 0.000 | 97.2 | ||||

| Vegetable | Raw Ca | 75.44 (53.00, 89.33) | 0.028 | 31.8 | 0.000 | 96.9 | 1.45 | 0.229 | 1.19 (0.90,1.56) |

| Raw NCb | 72.23 (35.92, 92.34) | 0.222 | 36.6 | 0.000 | 97.3 | ||||

| Water | Non pipe | 86.65 (82.17, 90.13) | 0.000 | 0.54 | 0.585 | 0 | 1.36 | 0.243 | 1.30 (0.85,2.00) |

| Pipe | 83.45 (76.73, 88.52) | 0.000 | 6.4 | 0.000 | 84.2 | ||||

| HIV | Positive | 81.06 (50.07, 94.81) | 0.05 | 77.7 | 0.000 | 98.7 | 0.26 | 0.609 | 1.06 (0.87,1.29) |

| Negative | 80.17 (72.47, 86.13) | 0.000 | 6.7 | 0.000 | 85.0 |

I2, inverse variance index; OR, odds ratio; Q, Cochran’s X 2; Y-p, probability of Yates test; Z-p probability of Z test

aConsumers

bNon-consumers

Discussion

The moderate to high inverse variance indexes of the study level estimates in food animals and humans reported here are suggestive of potential variations that could have been due to cat densities, environmental and societal factors [59, 60].

The prevalence of T. gondii in cats in Ethiopia was high. Ethiopian cats live outdoors, hunt, feed on scraps and garbage-thus more exposed to the parasite [3]. In a study from California, USA, the annual environmental burden per square meter was estimated to be in the range of 94 to 4671 oocysts, based on a low prevalence (0.9 %) of oocysts in cat feces [61]. Therefore, if we assume 17.51 % oocyst shedder cats in Ethiopia, and 100 million oocysts per shedder [1], the environmental burden in urban residential areas where cats abound is apparently high.

The overall pooled estimate in small ruminants was considerable (34.59 %), and the odds of infection was three times greater in adults than in young small ruminants. The higher occurrence of T.gondii infection in adults compared to young animals is in agreement with results of studies carried out elsewhere [62, 63]. The estimate demonstrates the potential of T. gondii as a cause of reproductive wastage in small ruminants, and the risk associated with the consumption of raw products derived from small ruminants [64, 65].

The substantially high prevalence of T. gondii infections in humans could be due to the uncontrolled movement of cats, the substandard living circumstances, and the unhygienic life styles and habits that favor the transmission of the parasite from either felids or food animals. Comparison of the present estimate with estimates for sub-Saharan African countries (SSA) is difficult because national survey reports or meta-analytical studies are scarce. However, the prevalence of T. gondii infection in Ethiopian women is apparently higher than estimates for most developed countries (4 % in South Korea to 11 % in USA) [60]. Therefore, assuming three million live births each year [66], and a conservative estimate of 0.1 % birth prevalence of congenital infections [67, 68], the number of congenitally infected neonates per annum could be about 3000.

T.gondii infection was higher in urban than in rural inhabitants and in individuals with cats in the household or had contact with cats. The cat population per unit area appears to be higher in the urban than in the rural areas because of the relatively better feed resource in the former than the latter, and as cats roam in search of food a single cat could be a source of infection to several neighboring urban households.

The high prevalence of T.gondii in HIV positive individuals suggests the risk of cerebral toxoplasmosis in patients that do not have access to HIV treatment. Cerebral toxoplasmosis is one of the sequels of T.gondii in HIV patients [69–71], and in the absence of chemo-prophylaxis against HIV, up to 40 % of patients co-infected with T. gondii may develop fatal Toxoplasma encephalitis [6]. Before the start of the highly active anti-reteroviral therapy (HAART) in Ethiopia, neural toxoplasmosis was one of the complications [72] with mortality in more than a third of the patients [72, 73], and after the initiation of HAART, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) was one of the sequels of toxoplasmosis [74–76].

To date, there have been only two studies that reported the prevalence of T.gondii in patients with schizophrenia/ bipolar disorders and the study level estimates were greater than 88 % [47, 49]. Meta-analytical studies have also shown higher odds of schizophrenia (OR = 2.73) [77, 78], and epilepsy (OR = 4.8) [13] in T.gondii seropositive than in seronegative individuals, and positive associations of T.gondii seroprevalence with traffic accidents [79–81], and suicide attempts and success [82] have been recorded elsewhere.

Implications and limitations

This study demonstrates the importance of toxoplasmosis in small ruminant production and its public health impact. The control of the disease in a country where most cats are stray, and the food animal management system is mainly of an extensive type is difficult. Therefore, public education as regards the value of cooked meat and washed vegetables, and hygienic practice could reduce the transmission of the parasite and the consequences of infection in humans. Secondly, although a large scale neonatal screening program and treatment of infected neonates at a national level is not an economically viable strategy against congenital infections, initiation of such a program at least in urban areas where there are individuals who afford the medical costs could somehow reduce the impacts of the disease to a limited extent.

As the numbers of eligible studies in each stratum were small and all regions of the country have not been covered in the studies, the estimates and the predictive values of the risk factors may vary depending on factors that may involve animal, environmental and societal variables. However, the pooled estimates highlight the overall magnitude of Toxoplasma infections in animals and humans in Ethiopia; the heterogeneity statistics show the variability of the study level estimates and potential areas of research, and the crude odds ratios depict the relative importance of the risk factors.

Conclusions

Toxoplasmosis is highly prevalent in Ethiopia, and could be a cause of considerable reproductive wastage in small ruminants and multiple diseases in humans. Educational programs, and serological screening and treatment of neonates when possible could help to reduce the national impacts of the disease. Further studies are needed to describe the epidemiology of the disease at a national level in Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jitender P. Dubey, for providing us with articles on the study.

Additional file

PRISMA Checklist.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EZG searched the literature and extracted the data; TG designed the study and analyzed the data; EZG and TG have participated in drafting the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Endrias Zewdu Gebremedhin, Email: endrias.zewdu@gmail.com.

Getachew Tadesse, Email: getadesse1@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé M. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012. doi:10.1128/CMR.05013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Dabritz HA, Conrad PA. Cats and Toxoplasma: implications for public health. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010;57:34–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubey JP, Tiao N, Gebreyes WA, Jones JL. A review of toxoplasmosis in humans and other animals in Ethiopia. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1935–8. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma oocysts as a public health problem. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:380–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis-a waterborne zoonosis. Vet Parasitol. 2004;126:57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis in sheep-the last 20 years. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii Infections in chickens (Gallus domesticus): prevalence, clinical disease, diagnosis and public health significance. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010;57:60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yolken RH, Bachmann S, Rouslanova I, Lillehoj E, Ford G, Torrey EF, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in Individuals with first-episode schizophrenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:842–4. doi: 10.1086/319221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanyüksel M, Uzun Ö, Araz E, Koru Ö, Babür C. Possible role of toxoplasmosis in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamdani N, Daban-Huard C, Lajnef M, Richard J-R, Delavest M, Godin O, et al. Relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder in a French sample, brief report. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:444–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogruman-Al F, Aslant S, Alcan S, Customer S, Turk S. A possible relationship between Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia: a seroprevalence study. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2009;13:82–7. doi: 10.1080/13651500802624738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling VJ, Lester D, Mortensen PB, Langenberg PW, Postolache TT. Toxoplasma gondii seropositivity and suicide rates in women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:440–4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318221416e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer BS. Meta-analysis of three case controlled studies and an ecological study into the link between cryptogenic epilepsy and chronic toxoplasmosis infection. Seizure. 2007;16:657–63. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yereli K, Balcioğlu IC, Ozbilgin A. Is Toxoplasma gondii a potential risk for traffic accidents in Turkey? Forensic Sci Int. 2006;163:34–7. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocazeybek B, Oner YA, Turksoy R, Babur C, Cakan H, Sahip N, et al. Higher prevalence of toxoplasmosis in victims of traffic accidents suggest increased risk of traffic accident in Toxoplasma-infected inhabitants of Istanbul and its suburbs. Forensic Sci Int. 2009;187:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA group preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Prevalence of low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2013. doi:10.1186/1471–2431–13–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hurley JC. Lack of impact of selective digestive decontamination on Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator associated pneumonia: benchmarking the evidence base. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1365–73. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galbraith RF. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med. 1988;7:889–94. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Li X, Zhou F, Jin Q, Gao L. Prevalence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in mainland China: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gao L, Zhang L, Jin Q. Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:354–58. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zewdu E, Agonafir A, Tessema TS, Tilahun G, Medhin G, Vitale M, et al. Seroepidemiological study of caprine toxoplasmosis in East and West Shewa Zones, Oromia Regional State, Central Ethiopia. Res Vet Sci. 2013;94:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebremedhin EZ, Agonafir A, Tessema TS, Tilahun G, Medhin G, Vitale M, et al. Seroepidemiological study of ovine toxoplasmosis in East and West Shewa Zones of Oromia regional state, Central Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res. 2013. doi:10.1186/1746–6148–9–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Teshale S, Dumetre A, Darde ML, Merga B, Dorchies P. Serological survey of toxoplasmosis in Ethiopia: prevalence and risk factors. Parasite. 2007;14:155–9. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2007142155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demissie T, Tilahun G. Study on toxoplasmosis in sheep and goats in Debre Birhan and surrounding areas in Ethiopia. Bull Anim Hlth Prod Afr. 2002;50:138–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negash T, Tilahun G, Patton S, Prevot F, Dorchies PH. Serological survey of toxoplasmosis in sheep and goats in Nazareth, Ethiopia. Revue Med Vet. 2004;155:486–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gebremedhin EZ, Gizaw D. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in sheep and goats in three districts of Southern nations, nationalities and peoples’ region of Ethiopia. World Appl Sci J. 2014;31:1891–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gebremedhin EZ, Abdurahaman M, Hadush T, Tessema TS. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in sheep and goats slaughtered for human consumption in Debre-Zeit, Central Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014. doi:10.1186/1756–0500–7–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gebremedhin EZ, Yunus HA, Tesfamaryam G, Tessema TS, Dawo F, Terefe G, et al. First report of Toxoplasma gondii in camels (Camelus dromedarius) from Ethiopia: seroepidemiology and bioassay. BMC Vet Res. 2014. doi:10.1186/s12917–014–0222–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Tilahun G, Tiao N, Ferreira LR, Oliveira S, Verma SK, Kwok OCH, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii from free-range chicken (Gallus domesticus) from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Parasitol. 2013. doi:10.1645/12–25.1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Gebremedhin EZ, Tesfamaryam G, Yunus HA, Duguma R, Tilahun G, Di Marco V, et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in free range chickens (Gallus domesticus) of Central Ethiopia. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;24:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gebremedhin EZ, Kebeta MM, Asaye M, Ashenafi H, Di Marco V, Vitale M. First Report on Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in pigs in Central Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res. 2015. doi:10.1186/s12917–015–0384–y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Dubey JP, Darrington C, Tiao N, Ferreira LR, Choudhary S, Molla B, et al. Isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii from tissues and feces of cats from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Parasitol. 2013;99:56–8. doi: 10.1645/GE-3229.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiao N, Darrington C, Molla B, Saville WJA, Tilahun G, Kwok OCH, et al. An investigation into the seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii, Bartonella spp., feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), and feline leukemia virus (FelV) cats from Addis Ababa. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:1029–33. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellbin T, Vahlquist B. The antibody pattern in representative groups of Ethiopian village children. Acta Paediat Scand. 1968;57:385–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1968.tb07309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Roever-Bonnet H. Toxoplasmosis in tropical Africa. Trop Geogr Med. 1972;24:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guebre-xabier M, Nurilign A, Gebre-Hiwot A, Hailu A, Sissay Y, Getachew E, et al. Seroepidemiological survey of Toxoplasma gondii infection in Ethiopia. Eth Med J. 1993;31:201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eshete H, Tessema S, Abebe S, Abebe A. Some notes on toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Addis Ababa. Correspondence. Ethiop Med J. 1994;32:135–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woldemichael T, Fontanet AL, Sahlu T, Gills H, Messele T, de Wit TFR, et al. Evaluation of Eiken latex agglutination test for anti-toxoplasmosis antibodies and seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis infection among factory workers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:401–3. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)91065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Negash T, Tilahun G, Medhin G. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Nazaret town, Ethiopia. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5:211–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yimer E, Abebe P, Kassahun J, Woldemical T, Bekele A, Zewdie B, et al. Seroprevalence of human toxoplasmosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Vet J. 2005;9:109–22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibre T, Alem A, Abdulahi A, Araya M, Beyero T, Medhin G, et al. Trimethoprim as adjuvant treatment in schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:846–51. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimelis T, Tebeje M, Tadesse E, Tegbaru B, Terefe A. Seroprevalence of latent Toxoplasma gondii infection among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected people in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2009. doi:10.1186/1756–0500–2–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Tedla Y, Shibre T, Ali O, Tadele G, Woldeamanuel Y, Asrat D, et al. Serum antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and herpesviridae family viruses in individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a case-control study. Ethiop Med J. 2011;49:211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zemene E, Yewhalaw D, Abera S, Belay T, Samuel A, Zeynudin A. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Jimma town, Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2012. doi:10.1186/1471–2334–12–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Gebremedhin EZ, Hailu A, Tessema TS, Desta K, Medhin G, Vitale M, et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in women of child-bearing age in Central Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013. doi:10.1186/1471–2334–13–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Aleme H, Tilahun G, Fekade D, Berhe N, Medhin G. Sereoprevalence of Immunoglobulin-G and of Immunoglobulin-M anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome patients at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Infect Dis Therapy. 2013. doi:10.4172/2332–0877.1000119.

- 53.Walle F, Kebede N, Tsegaye A, Kassa T. Seroprevalence and risk factors for toxoplasmosis in HIV infected and non-infected individuals in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2013. doi:10.1186/1756–3305–6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Muluye D, Wondimeneh Y, Belyhun Y, Moges F, Endris M, Ferede G, et al. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and associated risk factors among people living with HIV at Gondar University hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. ISRN Trop Med. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/123858.

- 55.Tadese A, Mathewos B, Abebe A, Dagbew M. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and associated risk factors among blood donors at Gondar University hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Pharm H Care Res. 2013;1:80–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Endris M, Belyhun Y, Moges F, Adefiris M, Tekeste Z, Mulu A, et al. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii in pregnant women attending in Northwest Ethiopia. Iranian J Parasitol. 2014;9:407–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeweld SW, Reta DH. Detection of zoonotic opportunistic infections in HIV/AIDS patients in selected residential districts of Tigray region, Ethiopia. J Environ Occup Sci. 2014;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yohanes T, Debalke S, Zemene E. Latent Toxoplasma gondii Infection and associated risk factors among HIV-infected individuals at Arba Minch hospital, South Ethiopia. AIDS Res Treat. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/652941 DOI:10.1155 %2 F2014%2 F652941#pmc_ext . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Pappas G, Roussos N, Falagas ME. Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flegr J, Prandota J, Sovičková M, Israili ZH. Toxoplasmosis-a global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in set of 88 countries. PLoS ONE. 2014; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Dabritz HA, Miller MA, Atwill ER, Gardner IA, Leutenegger CM, Melli AC, et al. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts in cat feces and estimates of the environmental oocyst burden. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;231:1676–84. doi: 10.2460/javma.231.11.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halos L, Thébault A, Aubert D, Thomas M, Perret C, Geers R, et al. An innovative survey underlining the significant level of contamination by Toxoplasma gondii of ovine meat consumed in France. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boughattas S, Ayari K, Sa T, Aoun K, Bouratbine A. Survey of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii in human consumed ovine meat in Tunis City. PLoS One. 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Jones JL, Dargelas V, Roberts J, Press C, Remington JS, Montoya JG. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:878–84. doi: 10.1086/605433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubey JP, Rajendran C, Ferreira LR, Martins J, Kwok OCH, Hill DE, et al. High prevalence and genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii isolated from goats, from a retail meat store, destined for human consumption in the USA. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:827–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.The state of the world’s midwifery, Part 4: Country profiles. Ethiopia [www.stateoftheworldsmidwifery.com]

- 67.Torgerson PR, Mastroiacovo P. The global burden of congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:501–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.111732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flegr J. How and why Toxoplasma makes us crazy. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goswami RP, Goswami RP, Rahman M, Ray Y, Tripathi SK. Alternative treatment approach to cerebral toxoplasmosis in HIV/AIDS: experience from a resource poor setting. Int J STD AIDS. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Akanmu AS, Osunkalu VO, Ofomah JN, Olowoselu FO. Pattern of demographic risk factors in the seroprevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in HIV infected patients at the Lagos University teaching hospital. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2010;20:1–4. doi: 10.4314/nqjhm.v20i1.57974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Addebbous A, Adarmouch L, Tali A, Laboudi M, Amine M, Aajly L, et al. IgG anti-Toxoplasma antibodies among asymptomatic HIV-infected patients in Marrakesh-Morocco. Acta Trop. 2012;123:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bane A, Yohannes AG, Fekade D. Morbidity and mortality of adult patients with HIV/AIDS at Tikur Anbessa teaching hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.BerheT, Melkamu Y, Amare A. The pattern and predictors of mortality of HIV/AIDS patients with neurologic manifestation in Ethiopia: a retrospective study. AIDS Res Therapy. 2012; doi: 10.1186/1742–6405–9–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Klotz SA, Mohammed AA, Woldemichael MG, Mitku MW, Handrich M. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a resource-poor setting. J Int Assoc Physicians in AIDS Care. 2009. doi:10.1177/1545109709332469. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Huruy K, Mulu A, Mengistu G, Shewa-Amare A, Akalu A, Kassu A, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome among HIV/AIDS patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Japanese J Infec Dis. 2008;61:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huruy K, Kassu A, Mulu A, Wondie Y. Immune restoration disease and changes in CD4+ T-cell count in HIV- infected patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy at Zewditu memorial hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AIDS Res Therapy. 2010. doi:10.1186/1742–6405–7–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, Yolken RH. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:729–36. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii and other risk factors for schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:642–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Flegr J, Klose J, Novotná M, Berenreitterová M, Havlícek J. Increased incidence of traffic accidents in Toxoplasma-infected military drivers and protective effect RhD. BMC Infect Dis. 2009. doi:10.1186/1471–2334–9–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Laura G-R, Sánchez-Orozco V, Rodríguez LR, Rodríguez S, Roig-Melo E, Sanromán RT, et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in drivers involved in road traffic accidents in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Parasit Vectors. 2013. doi:10.1186/1756–3305–6–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Flegr J, Havlícek J, Kodym P, Malý M, Zbynеk S. Increased risk of traffic accidents in subjects with latent toxoplasmosis: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:2–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malhotra S, Kaur N, Kumar P, Hans C, Bhatia MS. Toxoplasmosis and suicidal tendencies: is there an association? Delhi Psychiat J. 2004;12:160–5. [Google Scholar]