Abstract

Significance: Cardiac function is energetically demanding, reliant on efficient well-coupled mitochondria to generate adenosine triphosphate and fulfill the cardiac demand. Predictably then, mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with cardiac pathologies, often related to metabolic disease, most commonly diabetes. Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), characterized by decreased left ventricular function, arises independently of coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis. Dysregulation of Ca2+ handling, metabolic changes, and oxidative stress are observed in DCM, abnormalities reflected in alterations in mitochondrial energetics. Cardiac tissue from DCM patients also presents with altered mitochondrial morphology, suggesting a possible role of mitochondrial dynamics in its pathological progression. Recent Advances: Abnormal mitochondrial morphology is associated with pathologies across diverse tissues, suggesting that this highly regulated process is essential for proper cell maintenance and physiological homeostasis. Highly structured cardiac myofibers were hypothesized to limit alterations in mitochondrial morphology; however, recent work has identified morphological changes in cardiac tissue, specifically in DCM. Critical Issues: Mitochondrial dysfunction has been reported independently from observations of altered mitochondrial morphology in DCM. The temporal relationship and causative nature between functional and morphological changes of mitochondria in the establishment/progression of DCM is unclear. Future Directions: Altered mitochondrial energetics and morphology are not only causal for but also consequential to reactive oxygen species production, hence exacerbating oxidative damage through reciprocal amplification, which is integral to the progression of DCM. Therefore, targeting mitochondria for DCM will require better mechanistic characterization of morphological distortion and bioenergetic dysfunction. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 1545–1562.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for approximately ∼30% of deaths (160a). This percentage is elevated within patient populations with additional risk factors such as poor diet, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and elevated lipids, which are often associated with diabetes. Approximately 66% of the diabetic population will die of heart disease and, combined with stroke, it comprises the most prominent morbidity of type 2 diabetics (www.heart.org). A correlation between diabetic complications and mitochondrial dysfunction has been established in multiple tissues, in part through mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The underlying mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) has yet to be elucidated. Notably, cardiomyocytes from animal models of type 1 and 2 diabetes present with altered mitochondrial morphology, enhanced levels of ROS, and resulting cellular oxidative damage. More recently, similar observations were made in the atrial tissue from human diabetic subjects. Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia of diabetes induce mitochondrial fission, accompanied by an enhanced mitochondrial ROS level. In this sense, the aberrant mitochondrial morphology observed in DCM could be considered a possible underlying mechanism in the pathology.

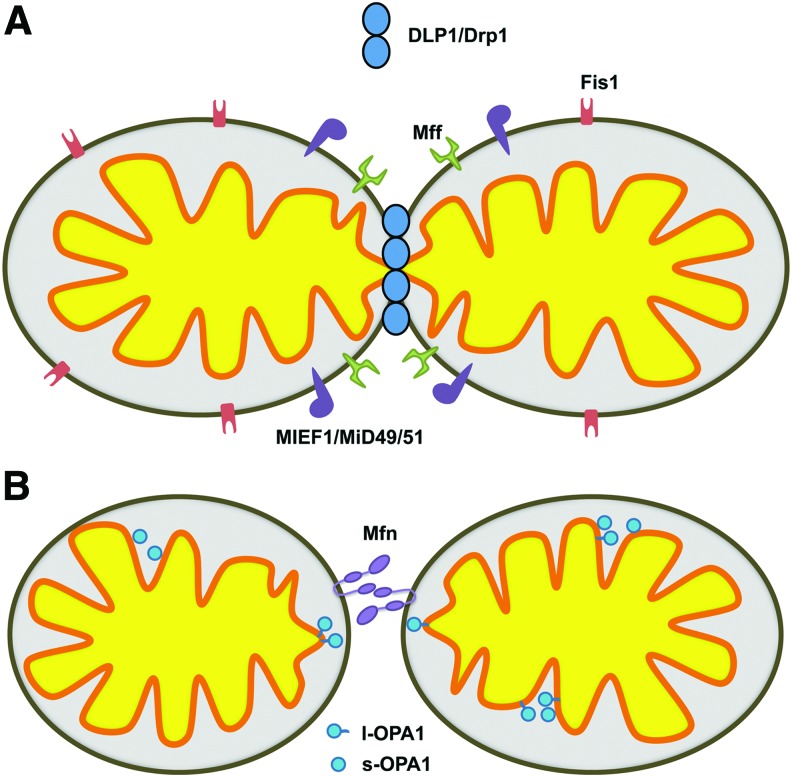

Mitochondrial morphology at any given moment is representative of the net balance of continual fission and fusion. Constant cycles of fission and fusion are essential to maintain cellular homeostasis, which requires meeting bioenergetic demand in response to a myriad of cellular stimuli. A group of dynamin-related large GTPases impart mitochondrial morphologic changes. These include dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1, also known as Drp1 for dynamin-related protein 1), mitofusin (Mfn), and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1). DLP1/Drp1 functions in constriction of the mitochondrial membrane during fission, whereas Mfn and OPA1 support fusion of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes, respectively (Fig. 1). There are two Mfn isoforms, Mfn1 and Mfn2, which have a redundant function in mitochondrial fusion. The Mfns are anchored in the outer membrane, tethering apposing mitochondria in fusion (94). In addition, Mfn2 is also found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane where it forms ER-mitochondria junctions (40). OPA1 is associated with the inner membrane where it mediates inner membrane fusion as well as the regulation of cristae morphology (33, 121). The fission protein DLP1/Drp1 lacks a transmembrane domain as well as the membrane-binding pleckstrin homology domain found in conventional dynamin, and is therefore primarily localized to the cytosol (141, 145, 166). The proper targeting of DLP1 to the mitochondria may involve a growing number of candidate receptors at the outer mitochondrial membrane, including Fis1, mitochondrial fission factor (Mff), and MIEF1/MiD49/51 (Fig. 1) (125, 126, 149, 165, 172). Of these postulated receptors, Mff appears to be the principal receptor for DLP1 localization to mitochondria (103, 125). In addition to the recognition of mitochondrial receptor proteins, the cellular localization of DLP1 is influenced by an array of post-translational modifications, most notably phosphorylation (24, 35, 72, 151, 167), as well as S-nitrosylation (30), sumoylation (16, 54, 74, 156), and ubiqutination (118, 163), altering its sub-cellular distribution, functional interactions, and stability. Highlighting the functional importance of mitochondrial fission and fusion, genetic deletion of DLP1, Mfn1, Mfn2, or OPA1 results in embryonic lethality (27, 39, 82, 153).

FIG. 1.

The primary proteins responsible for mitochondrial fission and fusion. (A) Mitochondrial fission is facilitated by the large GTPase DLP1/Drp1. DLP1/Drp1 recognizes the outer mitochondrial membrane resident receptors Mff, Fis1, or MIEF1/MiD49/51. (B) Outer mitochondrial membrane fusion is promoted by the tethering of adjacent mitochondria through the HR2 domains and GTPase activity of the outer mitochondrial membrane resident Mitofusins (Mfns). OPA1, resident to the inner mitochondrial membrane, supports inner mitochondrial membrane fusion. Proteolytic processing of the OPA1 protein results in both l-OPA1 (long) and s-OPA1 (short) variants. OPA1 is also implicated in cristae remodeling. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Cardiomyocytes have two well-defined populations of mitochondria that are spatially and functionally distinct: interfibrillar (IFM) and subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SSM). IFM are tightly packed between highly ordered myofibers and undergo quite a low frequency of fission/fusion cycle, estimated to occur every 16 days in murine hearts (29). Though infrequent, morphological dynamics of mitochondria in cardiac cells is essential for bioenergetic complementation, as the ablation of fusion restricts the normal exchange of mitochondrial components, reducing respiratory efficiency (29). Underpinning this requirement is the recently appreciated reciprocal influence between mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetic activity. The pathology of DCM displays mitochondrial morphologic alterations and energetic dysfunction, although their temporal relation in the progression of the disease remains undefined. Basic mechanisms of mitochondrial dynamics, including details about fission and fusion protein functions, have been the subject of many reviews (23, 26, 61, 62, 164). In this review, therefore, we will restrict our descriptions to the cardiac-related aspect and highlight the relationship between mitochondrial dynamics and energetic activity in the context of the DCM etiology.

Mitochondrial Dynamics in Cardiac Tissue

Despite the rigid structure and spatial constraint of the myofibril architecture in cardiomyocytes, the abundance of the proteins mediating mitochondrial fission and fusion suggests their importance in cardiac development and homeostasis. Next, we highlight the physiologic requirement for mitochondrial fission/fusion from embryogenesis through mature cardiac function.

Mitochondrial morphology and function in heart development

To meet the energetic demand of the developing heart, embryonic stem cells (ESCs) differentiating into cardiomyocytes undergo a metabolic switch from a glycolytic metabolism to oxidative phosphorylation. This cellular transition is accompanied by a nearly 40-fold increase of maximal respiratory capacity and a three-fold decrease in glycolysis. The metabolic switch occurs concomitantly with a transcriptional increase in enzymes and components supporting fatty acid oxidation, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the respiratory chain, and with suppression of lipid biosynthetic and glycolytic enzymes (32). Mitochondrial morphology changes during this metabolic transition, from small rounded mitochondria lacking well-ordered cristae in ESCs to elongated mitochondria with organized cristae in beating cardiomyocytes. Changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins mirror the morphologic transition with suppressed expression of DLP1 and increased expression of Mfn2 transcripts in differentiated cardiomyocytes. The pro-fusion phenotype in the differentiated cardiomyocytes creates filamentous mitochondria with distinctive spatial organization, aligning them within the sarcomere to sustain excitation-contraction coupling. Conversely, inhibition of respiration complexes disrupted sarcomere organization with dispersed and fragmented mitochondria, preventing differentiation to cardiomyocytes (32). These observations indicate that genetic reprogramming during cardiomyocyte differentiation regulates both mitochondrial energetics and structure, suggesting a close relationship between mitochondrial morphology and function.

Investigation of mitochondrial structure in the developing mouse embryo also revealed a shape transition associated with functional change (77). Ventricular myocytes from E9.5 embryos displayed fragmented mitochondria, with a round and dilated morphology. In contrast, E11.5 and E13.5 embryonic myocytes developed filamentous, interconnected networks of mitochondria. The lengthening of cardiac mitochondria was paralleled by the maturation of their cristae, transitioning from mitochondria with a vacuous appearance at E9.5 to condensed well-ordered cristae by E13.5. In parallel with mitochondrial shape change, the mitochondrial membrane potential was increased, which was found to be the result of closure of the permeability transition (PT) pore. The PT pore closure drove mitochondrial maturation and cardiomyocyte differentiation. The timing of the pore closure was between E9.5 and E13.5, immediately preceding differentiation to a septated heart, which requires increased energy supply. Likely, the PT pore closure favors coupling of oxidative phosphorylation, thus increasing the efficiency of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis.

In addition to mitochondrial shape transition associated with energetic switching in the developing heart, a recent study revealed a signaling function of mitochondrial fusion in ESC differentiation to cardiomyocytes (89). The differentiation of ESCs to cardiomyocytes correlated with the increased expression of both Mfn2 and OPA1. Ablation of either Mfn2 or OPA1 by gene trapping prevented ESCs from differentiating into a cardiomyocyte lineage (89). Mfn2 and OPA1 gene-trapped ESCs had similar mitochondrial membrane potential, respiration, and ATP levels as wild-type ESCs. However, disruption of mitochondrial fusion was associated with increased capacitative calcium entry, which enhanced Notch1 signaling by calcium-induced calcineurin activation. Inhibition of calcium and calcineurin signaling was sufficient to reverse the nondifferentiating phenotype of gene-trapped ESCs with no effect on mitochondrial morphology. This places mitochondrial dynamics upstream of Notch signaling for ESC differentiation into cardiomyocytes, supporting a regulatory role of mitochondrial dynamics in cardiac development.

Cardiac dysfunction may contribute to embryonic lethality in DLP1 knockout (KO) mice, suggesting the involvement of mitochondrial fission in cardiac development. It was reported that cardiomyocytes isolated from DLP1-knockout embryos had a reduced beating relative to those from wild-type controls (153). The reduced beating did not arise from abnormalities in cardiac structure or angiogenesis of the embryo (153). In contrast, another report observed a poorly developed cardiac structure in DLP1-KO embryos (82). These observations suggest that DLP1 ablation may cause structural and functional defect in the developing heart. Together, these observations indicate that morphologic and bioenergetic maturation of mitochondria is coordinately regulated in the developing heart and dysregulation of either process prevents normal development, causing embryonic lethality.

Mitochondrial fission and fusion in heart function

Disruption of mitochondrial fusion in mature cardiac tissue perturbs cardiac homeostasis, leading to cardiomyopathies in both fly and murine models (29, 45). In Drosophila, knockdown of mitochondrial assembly regulatory factor (MARF), the fly homolog of Mfn1/2, or OPA1 led to fragmented mitochondria and dilated cardiomyopathy (45). Recovery in MARF knockdown phenotype was accomplished with either hMfn1 or hMfn2 transgene expression, with hMfn2 supporting a more complete recovery. Utilizing the same approach, Eschenbacher et al. reported a similar dilated cardiomyopathy in fruit flies resulting from two separate rare human mutations (50). The point mutations M393I and R400Q of hMfn2 were unable to phenotypically rescue MARF knockdown flies. Two tandem transmembrane domains at the C-terminus of the Mfn protein pass through the outer mitochondrial membrane twice, locating three functional domains, the GTPase and two heptad repeat domains (HR1 and HR2), to the cytosolic face (94). The HR2 domain has been shown to form an antiparallel coiled coil structure with another HR2, which tethers apposing mitochondria (94). The Mfn2 mutations M393I and R400Q are within the HR1 domain, with the latter acting as a dominant negative, prohibiting recovery when co-expressed with wild-type hMfn2. These results were somewhat unexpected, as fusion initiation requires an HR2-HR2 interaction (94). Underlying the dominant negative effect may be the physical associations of the HR1 domain with the HR2 domain (79). In the proposed model, the HR1/HR2 association forms a “closed” conformation, sequestering the HR2 domain from interacting with HR2 of other Mfn2 on an adjacent mitochondrion (79). In this manner, the point mutation R400Q may enhance the interaction with HR2, inhibiting mitochondrial tethering and acting as a dominant negative.

While both Mfn1 and Mfn2 can support mitochondrial fusion, Mfn2 has a unique function in mediating tethering of the ER to mitochondria (40). Mfn1 and Mfn2 can form homotypic or heterotypic complexes (27, 52). Mfn2 can localize to the ER membrane where it interacts with Mfn1 or Mfn2 of the mitochondrial outer membrane, tethering the two organelles. Mfn2 is, therefore, important in maintaining the inter-organelle calcium regulation, which has significant implications in excitation-contraction-metabolism coupling of cardiomyocytes. Not surprisingly, Mfn2 is highly abundant in the heart compared with other tissues (136). With respect to the ER tethering role for Mfn2, the conditional cardiac loss of Mfn2 was associated with decreased mitochondrial energetics. While basal cardiac physiology and mitochondrial membrane potential were relatively normal with Mfn2 deletion, an observed reduction of the NAD(P)H/FAD+ ratio suggested TCA cycle deficiencies, limiting reducing equivalents to support ATP synthesis (28). The absence of Mfn2 would decrease sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)-mitochondrial contact, reducing mitochondrial calcium concentrations in calcium transients and thus limiting activation of dehydrogenases in the TCA cycle. Insufficient activation of TCA cycle dehydrogenases would impair energy supply. In addition, Mfn2-deficient cardiac cells were more resistant to calcium-induced PT and subsequent cell death, in agreement with the idea of disrupted calcium crosstalk with the decreased SR-mitochondria tethering, which would decrease SR-mediated mitochondrial calcium overload (28, 40, 117, 127).

Cardiac-specific Mfn1 ablation resulted in smaller spherical mitochondria, as one might expect in the deletion of the fusion protein. However, left ventricular dysfunction was not observed (128). In Mfn1 KO mice, cardiac mitochondria had similar respiratory capacity and membrane potential compared with control mice. This could be attributed to the redundant function of Mfn1 and Mfn2 in mitochondrial fusion in combination with Mfn2 being the predominant form in cardiac tissue. Despite their fragmented mitochondria, Mfn1 KO cardiomyocytes were less susceptible to ROS-stimulated cell death and the PT (128), potentially by decreasing ROS propagation through decreased mitochondrial connectivity. In contrast to a mild cardiac phenotype in Mfn1 or Mfn2 single ablation, the conditional double knockout (DKO) of Mfn1 and 2 in postnatal cardiac tissue resulted in lethal dilated cardiomyopathy (29). The loss of both Mfn1 and Mfn2 in cardiac tissue resulted in 40% smaller mitochondria, with reduced internal complexity (29). Cardiac mitochondria of Mfn1/2 DKO mice displayed reduced adenosine diphosphate-stimulated and maximal oxygen consumption rates, indicating defects in respiratory chain complexes. Although contractility and mitochondrial calcium transients were normal at 1 week after gene deletion, hearts of Mfn DKO were progressively dilated until death at 7–8 weeks by heart failure.

A mutagenic screen described the first instance of a mitochondrial fission defect resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy (7). Heterozygous transgenic mice with the mutation C452F in DLP1 resulted in a congestive heart failure pathology, with cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, while homozygosity for the mutation was embryonically lethal. Heterozygous hearts had a reduced mitochondrial function and were thus energetically insufficient. The C452F mutation is within the middle (M) domain of DLP1. DLP1 interactions at the M domain form DLP1 oligomers that constrict and sever the mitochondrial membranes for fission (7, 25, 129, 130, 173), indicating that this mutation may act as a dominant negative in a heterozygous background. Similarly, another M-domain mutation of DLP1 (A395D) found in humans was reportedly lethal (157). Indeed, fibroblasts generated from heterozygous C452F mice and A395D human DLP1 mutations showed an elongated fission-defective mitochondrial morphology (7, 157). In contrast, C452F heterozygous mice did not exhibit overt disruptions of cardiac mitochondrial morphology. Instead, electron micrographs of 10-week-old hearts revealed slightly smaller mitochondria, which is similar to the mitochondrial morphology observed in hearts of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (138). It is likely that the smaller mitochondria in the heart are the result of pathological fragmentation, which was sufficient to mask the incomplete penetrance of the mutant DLP1 in the heterozygous background.

Mitochondria in DCM

The observations described earlier suggest that mitochondrial dynamics have broad implications in heart development and function, regulating energetic activity as well as signaling. Alteration of mitochondrial energetics is closely associated with the development of DCM. In addition, metabolic excess of the diabetic milieu has a profound effect on mitochondrial dynamics. We will first review morphological and energetic changes of mitochondria in DCM, and later discuss the potential mechanisms associated with the development of the disease under metabolic stress.

Mitochondrial morphology and function in DCM patients

Given the high energetic demand of the heart, mitochondrial dysfunction has been frequently hypothesized as causal to DCM. While the first published description of DCM was more than 40 years ago (135), the etiology of the disease in human cardiac tissue at the molecular level, for rather obvious reasons, has been sparse. Using noninvasive 31P nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, left ventricular cardiac hypertrophy and suppressed systolic function were found to be correlated with a reduction in ATP levels (10), suggesting impaired mitochondrial function. Fatty acids are the primary source for mitochondrial ATP synthesis in cardiac tissue through acetyl-CoA provision to the TCA cycle as well as NADH/FADH2 to the respiratory chain. Cardiac steatosis is a hallmark of DCM (109, 134), suggesting improper metabolism of fatty acids in mitochondria in DCM. Anderson et al. demonstrated altered substrate utilization and bioenergetic dysfunction in humans using permeabilized myofibers from the right atrium, obtained from coronary artery bypass grafting patients. Permeabilized myofibers from diabetic patients exhibited elevated intramyocellular lipids and displayed reduced state 3 respiration (3), indicative of defects in respiratory complexes. Respiration defects were observed with complex I (glutamate) but not with complex II (succinate) substrates. In addition, myofibers from diabetic patients were also deficient in respiration with palmitoyl-L-carnitine as a substrate. Diminished mitochondrial function was associated with enhanced mitochondrial ROS emission and oxidative stress compared with nondiabetic patients (3). Subsequent studies indicated that energetically defective mitochondria from diabetic patients were more susceptible to Ca2+-induced PT and showed enhanced caspase activity (4). Mitochondrial dysfunction increases the propensity of cardiomyocyte death, which helps explain, at least in part, the observed incidence of heart failure in diabetic patients (76, 88). Despite functional defects and the reduced respiratory capacity of mitochondria from DCM patients, light scattering analyses suggested that there were no obvious changes in mitochondrial size or internal complexity (36). In contrast, electron microscopy showed a reduced length of the IFM in diabetic patients (115). This morphological change was accompanied with a reduction in the level of Mfn1. Interestingly, the Mfn1 level was inversely correlated with the HbA1C, suggesting that hyperglycemia drives mitochondrial remodeling. Croston et al. reported the strongest correlative risk associated with mitochondrial dysfunction to be the presence of hyperglycemia (36), designating hyperglycemia as the critical factor in the transition of mitochondrial energetic and morphologic disruption. Although these observations may provide some insight as to alterations in mitochondrial energetics and morphology in DCM patients, they were made with biopsies from the right atrium, not the left ventricular tissue where the DCM pathology is the most obvious.

Mitochondrial morphology and function in animal models of DCM

Given the restrictions to studying DCM in humans, the majority of our mechanistic understanding of the disease has been derived from animal models. These studies have also resulted in essentially all information about mitochondrial morphology compiled on the disease (Table 1). Models of DCM can be classified as type 1 or 2, with the latter representing about 90% of the human diabetic population. While enhanced oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and morphologic abnormalities represent common observations in DCM, a few discrepancies have arisen between animal models, the significance of which remains unresolved.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial Morphology and Energetics in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

| Diabetic tissue source | Mitochondrial population | Mitochondrial morphology | Bioenergetic phenotype | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human right atrial tissue from CABG patients | Total | NA | Reduced state 3 respiration | (3) |

| Reduced complex I-driven respiration | ||||

| Human right atrial tissue from CABG patients | IFM | Unchanged | Unchanged | (36) |

| SSM | Unchanged | Reduced state 3, complex I, and II-driven respiration | ||

| Reduced complex I and IV activity | ||||

| TYPE II diabetic patients | IFM | Fragmented mitochondria (reduced Mfn1 level) | Reduced state 3 respiration and RCR | (115) |

| Reduced Complex I and II/III activity | ||||

| OVE26 mouse type I diabetic | Total | Swollen and disordered cristae | Reduced state 3 respiration | (140) |

| Increase in disordered mitochondria | Reduced RCR | |||

| Akita mice type I diabetic | Total | Swollen and disordered cristae | Suppressed state 3 & 4 respiration | (20) |

| Increased mitochondrial content | Decreased ATP synthesis | |||

| STZ injected mice type I diabetic | IFM | Decreased size and internal complexity | Reduced Complex I, II, and III-driven respiration | (38) |

| SSM | Unchanged | Reduced Complex II-driven respiration | ||

| Lepob mouse type II diabetic | Total | NA | Reduced state 3 respiration in glucose-perfused hearts (no change in ATP/O) | (14) |

| Reduced ATP synthesis and ATP/O in palmitate/glucose-perfused hearts (uncoupling | ||||

| Reduced complexes I, III, and V levels | ||||

| Lepob mouse type II diabetic | Total | Disordered cristae | NA | (44) |

| LepRdb mouse type II diabetic | Total | Disordered cristae | Increased FA utilization | (11, 15, 78) |

| Decreased glucose utilization | ||||

| Decreased state 3 respiration with Pyr, Glu, and palmitoylcarnitine | ||||

| LepRdb mouse type II diabetic | IFM | Increased internal complexity | Reduced state 3 respiration with Glu/Mal and palmitoylcarnitine | (37) |

| Reduced Complex I, III, and IV activity | ||||

| SSM | Decreased size and internal complexity | Unchanged |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; FA, fatty acid; Glu, glutamate; Mal, malate; NA, not analyzed; Pyr, pyruvate; RCR, respiratory control ratio.

Previous work implicating mitochondrial dysfunction and deformation in type 1 diabetes was conducted by the Epstein lab using the OVE26 mouse model that overexpresses calmodulin in pancreatic β-cells, in turn suppressing insulin secretion (140). The IFM region of these mice contained highly disordered and morphologically abnormal mitochondria with less dense and swollen cristae. Distorted morphology was concomitant with impaired mitochondrial energetics showing decreased state 3 respiration, low respiratory control, and enhanced oxidative damage. Anti-oxidant enzymes that reduce ROS in cardiomyocytes were sufficient to rescue cardiac function in diabetic mice without hyperglycemic reversal (100, 139, 162), indicating the causal role of ROS for cardiac dysfunction in diabetes. Furthermore, overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) in diabetic mice restored normal mitochondrial morphology (139), suggesting that mitochondrial ROS are responsible for morphological alterations. Akita mice are another animal model of type 1 diabetes via β-cell toxicity promoted by misfolded pro-insulin. These mice exhibited abnormal mitochondrial morphology and energetics similar to OVE26 mice. Cardiac tissue from Akita mice displayed swollen mitochondria lacking a well-defined cristae structure along with decreased states 3 and 4 respiration and ATP synthesis (20). Interestingly, increased mitochondrial density was observed in both OVE26 and Akita mice despite decreased mitochondrial energetic function, suggestive of defective clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy.

Pharmacologic β-cell ablation with streptozotocin (STZ) has also been used to model cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetes (9, 38, 87, 120, 160). The Hollander laboratory defined a specific subset of mitochondria, IFM, to be dysfunctional in cardiomyocytes from STZ-treated mice (9, 38, 160). In diabetic mice, the IFM, but not SSM, were smaller as judged by light scattering (38). Electron microscopy also indicated fragmentation of IFM in left ventricular samples from STZ-induced diabetic mice (62). In addition, a less complex mitochondrial internal structure was also observed, which was attributed to a reduction in mitofilin (9), an inner membrane protein involved in cristae remodeling (86). Accompanying the morphological defects were mitochondrial energetic deficiency with enhanced ROS levels and oxidative damage (38), leading to increased sensitivity to PT and apoptotic cell death (160).

DCM and its associated mitochondrial dysfunction have been observed in Lepob, LepRdb, and high fat-fed mice, representative of obesity-driven type 2 diabetic states (11, 14, 19, 37, 108). Consistent with the clinical manifestation of DCM, Lepob mice exhibit cardiac steatosis along with reduced diastolic function (31). Interestingly, an increased utilization of fatty acids was observed with decreased cardiac efficiency in Lepob mice (108). Increased fatty acid oxidation coupled with decreased cardiac performance is symptomatic of mitochondrial dysfunction, which is likely respiration uncoupling based on an increased activity of uncoupling proteins (UCP2 or UCP3) observed in this model (14, 15). UCP3 has been shown to regulate mitochondrial coupling and cardiac efficiency in high fat-fed models of DCM, but not in Lepob mice. Electron micrographs from 12-week-old Lepob mice revealed disordered cristae (44). However, no noticeable changes in cristae density were observed in Lepob mice at 4–5 weeks of age, indicating a gradual structural distortion over time (144).

Aberrant mitochondrial morphology was initially observed in LepRdb mice, where it preceded the loss of myofilaments and atrophy of myocytes (67). The structural abnormality of mitochondria was described as “shrinkage and increased electron density that were enveloped by single limiting membranes that in turn gave rise to large residual bodies,” suggestive of autophagosomal removal of mitochondria. Subsequent respiration measurements revealed suppressed state 3 respiration as early as 8 weeks of age, which was accompanied by lipid accumulation (95). Mitochondrial morphologic changes were restricted to the SSM population, along with the impaired respiration (37). Consistent with the Lepob model, ex vivo cardiac perfusion of LepRdb hearts demonstrated elevated fatty acid oxidation and reduced cardiac efficiency (78), possibly due to uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Interestingly, enhanced fatty acid oxidation and reduced cardiovascular efficiency precede the incidence of hyperglycemia in both LepRdb and Lepob mice (17). Enhanced fatty acid oxidation alone is sufficient to increase mitochondrial ROS to trigger insulin resistance through JNK activation in hepatic cells (119). A precedent also exists for leptin stimulation of ROS generation through the activation of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) and enhanced mitochondrial β-oxidation (161). Hyperleptinemia is present in the LepRdb and obese humans, but absent in the Lepob. Possibly, a leptin-induced increase of ROS, activates UCPs and decreases cardiac efficiency in LepRdb mice.

Cardiac ischemia-reperfusion–another type of metabolic insult

Ischemia as a result of disrupted blood flow to the tissue is characterized by decreased substrate. Blood flow restoration on reperfusion causes nutrient excess through enhanced metabolic flux, resulting in pathophysiological levels of ROS and oxidative stress, similar to diabetic conditions. Studies indicate that changes in mitochondrial morphology occur in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury and that manipulation of mitochondrial dynamics can affect the IR pathology. Mitochondrial fission occurs during simulated ischemia and the inhibition of mitochondrial fission delayed PT pore opening and is protective against cell death after reperfusion in a cardiac cell line (122). The promotion of mitochondrial elongation, through either the overexpression of fusion proteins Mfn1/Mfn2 or a dominant-negative fission protein DLP1-K38A, reduced cell death nearly four-fold in all cases. Conversely, imposing mitochondrial fragmentation with the overexpression of Fis1 enhanced cell death in a simulated IR model (122), consistent with the enhanced propensity of immortalized cells to undergo apoptosis with its overexpression (84).

In rat heart, IR has been shown to decrease the Mfn2 level in the infarct region and to increase DLP1 translocation to mitochondria in both infarct and peri-infarct regions (170). Inhibition of mitochondrial fission, with the overexpression of DLP1-K38A, decreased infarct size and protected cardiac function during IR injury (170). A small-molecule inhibitor for DLP1, mdivi-1, was also effective in reducing infarct size in IR injury in an in vivo murine model (122). Similarly, the cell-permeable dynamin inhibitor Dynasore, which targets dynamin in vitro (104), was protective of cardiac function in IR, minimizing infarct size in a Langendorff model (64). These observations showed that maintaining long tubular mitochondria in IR is protective against harmful injury. MicroRNAs have been found to regulate mitochondrial fission, and thus can limit the IR injury outcome. The microRNA miR-499 is an endogenous cardio-protective element functioning through the regulation of mitochondrial morphology in ischemic injury. miR-499 directly targets calcineurin catalytic subunits, inhibiting DLP1 dephosphorylation (154). Ischemia led to the suppression of miR-499 levels, allowing calcineurin to dephosphorylate DLP1, which promotes mitochondrial fission and cell death. Another microRNA, miR-761, suppresses the DLP1 receptor Mff, decreasing mitochondrial fission (102). Similar to miR-499, miR-761 is suppressed during an ischemic insult, promoting mitochondrial fission. Hence, transgenic overexpression of miR-761 or miR-499 decreased apoptotic cell death and infarct size in IR injury (102, 154).

The decreased IR injury outcome through control of mitochondrial morphology is similar to the protective effect imparted by the overexpression of Mfn2 or DLP1-K38A in hyperglycemia (168, 169). This protection was achieved through the suppression of mitochondrial ROS production by mitochondrial elongation under hyperglycemia (168, 169). Opening of PT pore and enhanced ROS upon reperfusion are major causes of IR injury (65, 71, 175, 176), which, in part, parallels metabolic insult associated with DCM.

Mitochondrial Dynamics and Bioenergetics in Diabetic Pathology

As discussed, deficiencies in mitochondrial energetics are commonly found in DCM. Structurally, mitochondria in this pathology are usually swollen with disrupted internal organization, likely representing a terminal phenotype of damaged mitochondria from oxidative stress and in association with apoptosis or autophagic degradation. In addition, in vitro studies indicated that acute hyperglycemic insult/stimulation induces a rapid formation of small mitochondria, which may reflect a change in energetics in response to metabolic excess. We will review the mechanistic aspect of mitochondrial morphology change during the progression of diabetic pathology and discuss the potential underlying mechanisms by which controlling mitochondrial morphology can provide protection for diabetic pathology.

Effects of diabetic milieu on mitochondrial fission and fusion

The pathophysiology of diabetes has a direct effect on mitochondrial morphology, at least in part through elevated plasma glucose levels. Depending on the stage of diabetes progression, an enhanced free fatty acid flux via improperly regulated lipolysis at adipose tissue is also likely present (70). Changes in mitochondrial morphology occur coordinately with metabolic flux, changing morphology in both an excess and lack of nutrients. Generally, mitochondria become smaller in response to increased metabolic flux (49, 53, 59, 60, 85, 91, 99, 105, 107, 114, 124, 147, 158, 167–169, 171) while elongating in response to starvation (68,133). Acute hyperglycemic conditions induce the formation of short and small mitochondria in a rapid response occurring in the order of minutes mediated by the fission protein DLP1 (168). The acute response depends on a post-translational modification mechanism, which may involve the phosphorylation of DLP1 at serine 616 through glucose-induced intracellular calcium transient and activation of ERK1/2 (167). Phosphorylation of DLP1 at serine 616 by PKCδ, Cdk1, and CDK5 has also been shown to increase the fission activity of DLP1 (132, 150, 151). A rapid formation of small mitochondria under acute metabolic stress causes mitochondrial ROS elevation, whereas pathologic fragmentation of mitochondria is associated with chronically elevated ROS levels and apoptotic cell death during sustained hyperglycemia (60, 63, 105, 106, 112, 114, 168, 169).

Chronic hyperglycemia was reported to suppress the expression of the fusion protein OPA1 while the DLP1 level was increased in coronary endothelial cells isolated from a mouse model of type 1 diabetes, supporting a pro-fission phenotype of mitochondrial morphology (105). These cells had increased superoxide levels, and the fragmented mitochondrial morphology was reversed with antioxidant treatment, indicating that ROS are causal of mitochondrial fragmentation (105). Subsequent studies in murine diabetic models revealed that enhanced O-GlcNAcylation of both OPA1 and DLP1 contributes to mitochondrial fragmentation (66, 106). O-GlcNAc modification of OPA1 was reported to inhibit its function, resulting in fragmented mitochondria with reduced membrane potential and complex IV activity (106). In contrast, O-GlcNAcylation of DLP1 stimulated GTP-binding activity and enhanced DLP1 translocation to mitochondria (66). Mechanistically, O-GlcNAc modification at Thr585 and 586 of DLP1 resulted in decreased Ser637 phosphorylation (66). It has been shown that DLP1 phosphorylation at Ser637 by protein kinase A (PKA) decreases mitochondrial fission, whereas dephosphorylation by calcineurin promotes DLP1 binding to mitochondria and enhances fission (22, 24, 35). Specific to DCM, enhanced O-GlcNAc modification was reported to correlate with the disease progression in a type 2 diabetic model, with the reversal of the modification recovering cardiac function (58). Ser637 of DLP1 is also the site for ROCK1-mediated phosphorylation (155). Unlike PKA-mediated phosphorylation, ROCK1-phosphorylated DLP1 binds to mitochondria, increasing mitochondrial fission (155). Consequently, genetic ablation of ROCK1 in mice prevented mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis under diabetic conditions and was beneficial in diminishing diabetic pathology, whereas overexpression of ROCK1 exacerbated it.

Mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetics: a reciprocal relationship

The influence of mitochondrial energetics on morphology was implied from changes in mitochondrial shape in response to mutations in complex I in the electron transport chain (ETC) (92). When mutations within mitochondrial genome-encoded subunits of complex I were complemented through cell fusion, mitochondrial morphology was recovered along with mitochondrial energetic function. Pharmacologic inhibition of ETC complexes is also sufficient to induce morphological changes in mitochondria (12, 42, 101). Benard et al. observed mitochondrial fragmentation and donut formation with complex I inhibition by rotenone. Similarly, the inhibition of complexes I and III produced a fragmented phenotype mediated by DLP1(42). Treatment of neurons with the complex II inhibitor 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP) resulted in mitochondrial fragmentation. Two different phases of mitochondrial changes were observed with 3-NP treatment: first an immediate decrease in cellular ATP, then followed by a secondary increase in ROS and mitochondrial fragmentation (101). A common factor in respiratory complex inhibition is an increased ROS, which has been reported to promote mitochondrial fission (105, 131). Mitochondrial fragmentation in these cases was associated with a lower membrane potential resulting from energetic dysfunction. Similarly, treatments with pharmacologic uncouplers resulted in mitochondrial fragmentation (81, 98, 110). Mitochondrial fusion requires proper inner membrane potential, and thus mitochondria are terminally fragmented with a loss of membrane potential (98, 111).

The functional significance connecting mitochondrial fragmentation and depolarization was revealed by the discovery that a reduced mitochondrial membrane potential in a fragmented mitochondrion was associated with autophagic removal (152). Twig et al. observed that the majority of mitochondrial fission events resulted in daughter mitochondria with asymmetric membrane potential, that is, one was hyperpolarized while the other was depolarized. The depolarized mitochondria underwent autophagy in the absence of regenerated membrane potential. Although the mechanism generating the uneven distribution of membrane potential in daughter mitochondria during fission remains undefined, the sequestration of depolarized mitochondria for autophagic removal is presumed to be mediated by the proteolytic processing of OPA1 (47, 48, 80, 146). OPA1-mediated fusion has been suggested to require both long (l-OPA1) and short (s-OPA1) forms of OPA1 (146). Mitochondrial depolarization activates inner membrane-associated metalloprotease OMA1, which cleaves l-OPA1, giving rise to a predominantly s-OPA1 population, preventing fusion of the depolarized mitochondria (48). This regulatory mechanism suggests that OPA1 can play a role as a bioenergetic sensor that links mitochondrial functionality to morphology and quality control.

While nutrient excess is associated with a pro-fission phenotype of mitochondria, mitochondrial elongation is prevalent in nutrient depletion (68, 133). Cells under nutrient deprivation showed an increase in ATP levels. This response was dependent on OPA1-mediated fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane, promoting increased cristae density, facilitating ATP synthase dimerization (68). In addition, nutrient starvation inhibits mitochondrial fission, through DLP1 phosphorylation at Ser 637 by PKA and dephosphorylation at Ser 616, contributing to a pro-fusion phenotype (68, 133). Elongated mitochondria under nutrient starvation are spared from autophagic degradation and maintain their energetic function (68, 133).

Progressive changes of mitochondrial energetics and morphology in diabetes

Given the reciprocal relationship between mitochondrial morphology and energetics described briefly earlier, a role for mitochondrial morphologic change in the establishment and/progression of diabetic pathology can be predicted. In vitro observations have shown that acute glucose stimulation induces the formation of short and condensed mitochondria, which is accompanied with augmented respiration, membrane potential, and ROS levels (114, 168, 169). Most in vivo evidence obtained under chronic diabetic conditions indicates mitochondrial energetic dysfunction with disrupted internal structure, ROS-induced oxidative stress, and cell death.

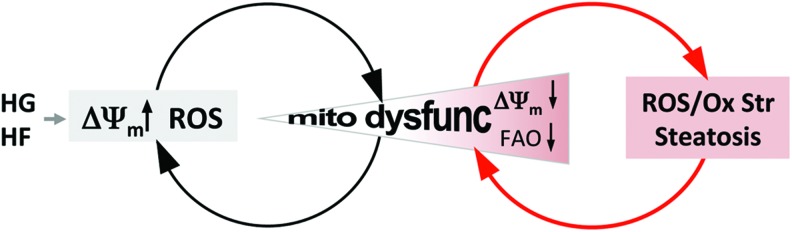

ROS overproduction in the respiratory chain has been shown to be the major cause for diabetic and obese pathophysiology under hyperglycemic and hyperlipidemic conditions. Within the respiratory chain, ROS production is more pronounced when electron transfer becomes slow, which occurs with mitochondrial hyperpolarization or respiratory complex dysfunction (73, 93, 139). We predict the following sequence of events in mitochondria from diabetic tissue. At the onset of diabetes, an initial increase of glucose and fatty acid oxidation stimulates respiration, increasing reducing equivalents (NADH and FADH2) availability to the respiratory chain. The increased flux of reducing equivalents overloads the respiratory chain, hyperpolarizing the membrane, favoring electron slippage and ROS production. Repeated hyperpolarization-induced ROS production would continue until oxidative modifications impair mitochondrial respiratory complexes. This establishes the subsequent phase of pathological ROS production from dysfunctional mitochondria, which intensifies oxidative damage in a vicious amplifying cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production (Fig. 2). Alternatively, the redox-optimized ROS balance hypothesis (R-ORB) has been proposed for an increase of mitochondrial ROS levels and oxidative stress (6, 34). In this hypothesis, the redox environment plays a crucial role in the emission of ROS, considering the net balance of ROS generation and ROS scavenging. A diminished pool of endogenous antioxidant, reduced glutathione, allows an increased emission of ROS (6, 34), contributing to the pathologic amplification of oxidative stress, via a shift in the redox environment with antioxidant defenses that are unable to offset ROS production. Enhanced ROS production via inhibition of TrxR2 in cardiac mitochondria supports this hypothesis (6, 148). The in vivo overexpression of mitochondria phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (mPHGPx) also rescued the energetic and ROS dysregulation in an STZ-induced type I diabetic mouse model as well as mitochondrial morphologic changes (8). Regardless of the route to establish mitochondrial dysfunction, once dysfunctional, diminished mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation would exacerbate steatosis (Fig. 2). Dysfunctional mitochondria at the late stage of the pathology exhibit a fragmented and swollen morphology. In contrast, the rapid formation of short and small mitochondria in response to acute exposure to metabolic excess may represent an activation of mitochondrial energetics, leading to mitochondrial hyperpolarization and ROS production.

FIG. 2.

The amplification of mitochondrial insult and dysfunction in diabetic conditions. Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia are two hallmarks of diabetes, both of which can hyperpolarize mitochondria causing electron slippage and enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Iterative rounds of excess metabolic flux modify the mitochondrial proteome, genome, and lipidome through ROS-mediated oxidative modifications, impairing mitochondrial function. Cumulative damage to mitochondria triggers the next pathologic phase of ROS production from impaired respiratory complexes, which further exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production through a vicious amplifying cycle (denoted by red arrows). The impairment of mitochondrial energetics impedes high-fat metabolism by β-oxidation, resulting in steatosis. Cardiac steatosis promotes wall stiffening, thereby decreasing cardiac function. It also leads to inflammation and fibrosis in an oxidative environment. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

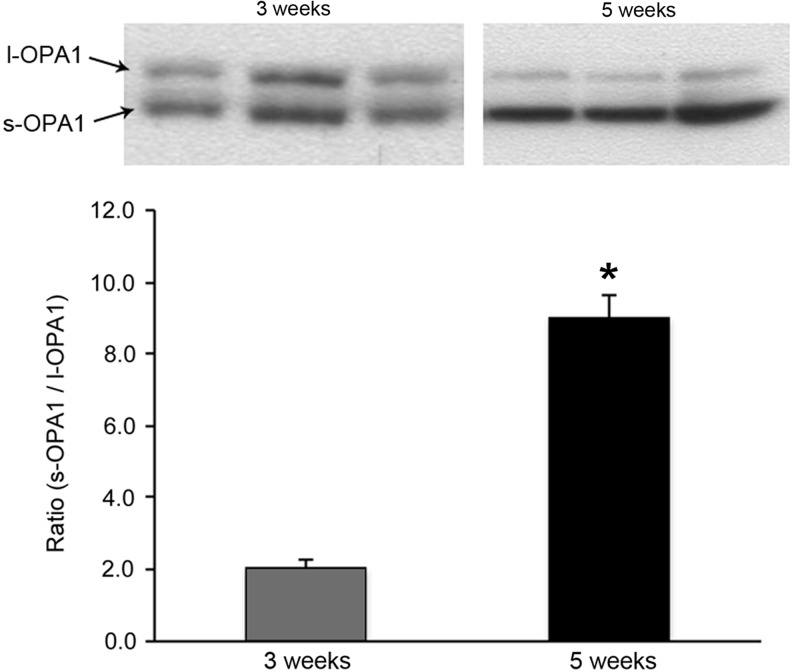

In this framework, two distinct phases in the disease progression can be distinguished in terms of mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetics. Identifying this pathological transition would be important for early therapeutic intervention. In our studies, we observed a clear difference in mitochondrial structure and ROS-producing capacity between 3 and 5 weeks of hyperglycemia in the heart of a type 1 diabetic animal model, suggesting the existence of a pathological transition. Electron microscopy of left ventricular samples from 3-week diabetic mice showed a “normal” morphological appearance, with well-ordered cristae and no apparent swelling (Fig. 3). In contrast, hearts from 5-week diabetic mice revealed distorted vacuous mitochondria with markedly diminished matrix electron density, suggestive of energetic dysfunction (Fig. 3). Coincident with the structural change in mitochondria, there was an increase of OPA1 cleavage in 5-week versus 3-week diabetic hearts, showing a markedly increased s-OPA1/l-OPA1 ratio (Fig. 4). The proteolytic cleavage of OPA1, generating s-OPA1, likely contributed to the vacuous cristae structure observed in electron microscopy as well as more fragmented mitochondria by decreasing mitochondrial fusion in diabetes. We also examined the ROS-producing capacity of the respiratory chain in permeabilized myofibers from 3- to 5-week diabetic hearts to compare respiratory complex functionality. The complex II substrate succinate was used to monitor ROS production by forward and reverse electron transport. While there were no differences in the rate of ROS produced in 3-week diabetic and control mice, 5-week diabetic hearts displayed a significant increase in the rate of ROS production with succinate, indicating respiratory complex dysfunction (Fig. 5). In the presence of rotenone with succinate as a substrate, a nearly seven-fold overall decrease in the ROS-production rate indicates that ROS production through the reverse electron transport is predominant in these experimental conditions. Importantly, 5-week diabetic hearts still showed a significantly increased rate of ROS production, indicating the increased ROS production in forward electron transport as well. The significant increases of ROS production by both forward and reverse electron transport suggest overall impairment of respiratory complexes in 5-week diabetic hearts. These observations support not only a correlation between altered mitochondrial morphology/structural organization and dysfunction but also the aforementioned pathological transition occurring during the progression of DCM associated with type 1 diabetes in this animal model. As for more prevalent type 2 diabetes, the aforementioned studies of Lepob mice suggest a progressive alteration of mitochondrial structure (44, 144), supporting a potential pathological transition. The critical role of mitochondrial morphology in DCM is a relatively new concept. Further systematic evaluation of mitochondrial morphology and function will be necessary during the progression of DCM.

FIG. 3.

Disordered left ventricular intrafibrillar mitochondria with a poor cristae structure developed between 3 and 5 weeks of type I diabetes. Electron microscopy was used to observe the mitochondrial morphology of left ventricular samples from age-matched male mice injected with streptozotocin. Cardiac tissue from 3-week diabetic mice displayed a “normal” morphological appearance of IFM, tightly packed between myofibrils with electron dense matrices and organized cristae (top panel). Mice diabetic for 5 weeks exhibited an altered morphologic appearance with vacuous mitochondria possessing poorly developed cristae (bottom panel).

FIG. 4.

A change in the relative amount of l- and s-OPA1 in diabetic progression of cardiac tissue. OPA1 exists in full length, l-OPA1, or proteolytically cleaved forms, s-OPA1. A mixture of the two is presumably required to support IMM fusion and cristae junction formation. Immunoblotting of left ventricular samples shows a marked increase in s-OPA1 with a concomitant decrease in l-OPA1 in 5-week diabetic mice compared with 3-week diabetic mice (*p≤0.05), demonstrating the enhanced cleavage of OPA1 during disease progression.

FIG. 5.

Mitochondrial dysfunction occurs between 3 and 5 weeks after the onset of type I diabetes. Permeabilized cardiac myofibers were assessed for their propensity to produce ROS with succinate as a substrate. H2O2 emission was monitored using amplex red in saponin-permeabilized cardiac myofibers from 3- to 5-week diabetic mice. The rate of ROS emission was normalized with respect to a hydrogen peroxide standard and the weight of the permeabilized myofiber. No significant differences in the rate of H2O2 emission were observed at 3 weeks relative to the control, whereas they were significantly increased (*p≤0.05) in myofibers from 5 week diabetic animals. The increased ROS production in the 5-week diabetic hearts was still present with rotenone that blocks reverse electron flow to complex I, indicating the increased ROS production in forward electron flow. The increases of ROS emission by both forward and reverse electron transport suggest overall impairment of respiratory complexes in 5-week diabetic hearts.

Controlling mitochondrial energetics through morphological manipulation: the mechanism behind targeting mitochondrial morphology for therapeutic application

In experimental models, many reports have indicated that inhibiting mitochondrial fission or increasing fusion has beneficial effects on not only metabolic disorders, including diabetes, but also other pathologies, notably tissue IR injury and neurodegenerative diseases (26, 64, 90, 122). One common cause in these pathologies is oxidative stress that leads to cell injury. Mitochondrial fission and fusion have been implicated in apoptotic and necrotic cell death in which mitochondrial fragmentation is mostly an inevitable process for the progression of cell death (56, 97, 159). Maintaining long filamentous mitochondria through manipulation of mitochondrial dynamics has been shown to prevent or delay cell death (51, 56, 122, 133, 169). Therefore, the protective mechanism by fission/fusion intervention can be attributed to its action on the cell death process, which prevents the late exacerbating phase of the pathology (Fig. 2). Importantly, studies have shown that inhibition of mitochondrial fission decreases initial ROS production in metabolic excess conditions (114, 168), indicating that fission inhibition can be an early intervention for preventing progression of the disease.

Decreasing ROS levels via proton leak/uncoupling is one of the possible mechanisms by which fission inhibition may produce its beneficial effect (60). The propensity for electron slippage and free radical generation from the respiratory chain is enhanced with mitochondrial hyperpolarization, and the relief contributed by uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation decreases ROS production (13, 69, 75, 93, 142). As would be predicted, inhibition of DLP1 function in experimental models of enhanced metabolic flux decreased ROS levels and oxidative stress across multiple tissue types, which was associated with respiration uncoupling (21, 59, 60, 170). Although some variations were observed in different experimental systems showing no change versus depression of certain components in oxygen consumption in DLP1 inhibition, respiration uncoupling was found as a common energetic change induced by fission inhibition (21, 59, 60, 170). A potential mechanism by which fission inhibition increases proton leak was the formation of long interconnected mitochondria (60, 96). Spontaneous transient depolarization has been observed as an intrinsic property of mitochondria (5, 18, 41, 43, 46, 83, 174), which is presumed to be a protective mechanism to prevent calcium overload and ROS production. We reported that fission deficiency greatly increased this spontaneous depolarization by inducing mitochondrial interconnection (60, 96). The spontaneous transient depolarization in normal cells would occur locally in discrete mitochondria, thus having minimal effect on overall cellular mitochondrial function. In fission deficiency, however, a local depolarization becomes global throughout interconnected mitochondria, as long filamentous mitochondria are electrically connected (1, 143). Therefore, fission deficiency greatly amplifies spontaneous depolarization, exhibiting increased inner membrane proton leak in respiration measurements.

Recent studies indicate that the inner membrane dynamin OPA1 plays a role in transient depolarization (96, 137). Santo-Domingo et al. reported that matrix pH increases (pH flash) in response to spontaneous depolarization, which is greatly augmented in fission deficiency (137). Based on the observation that the pH flash was ablated in OPA1-null cells, it was proposed that transient inner membrane fusion of adjacent mitochondria by OPA1 induces electrical coupling but disequilibrium in membrane potential in the two fusing mitochondria; thus, the observed mitochondrial depolarization and pH flash are the electrochemical re-equilibration process. In contrast, however, it was found that the already fused inner membrane of DLP1-null cells still requires OPA1 for depolarization, suggesting that fusion between inner membranes is not required for the depolarization events (96). Transient matrix bulging was found to precede depolarization. OPA1 may mediate ectopic fusion between inner and outer membranes closely contacted by matrix bulging, forming a transient lipid channel for matrix leak (96). Interestingly, increased proteolytic cleavage of OPA1 was observed in DLP1-null cells as well as with DLP1 silencing (96, 116). The cleavage of l-OPA1 to s-OPA1 occurs with a loss of membrane potential. Therefore, frequent large-scale depolarization in fission deficiency may accumulate s-OPA1. However, in opposition to the paradigm that OPA1 cleavage inhibits fusion, a new study indicates that OPA1 cleavage is associated with an increase of inner membrane fusion, possibly by activating GTPase activity, suggesting that OPA1 cleavage is a driving event for membrane fusion (113). In addition, OPA1 has been shown to function in cristae remodeling, which may not involve its membrane fusion activity (57). Furthermore, a recent report suggests that s-OPA1 mediates fission of the inner membrane (2), adding an additional layer of complexity to the functionality of OPA1. How OPA1 mediates transient depolarization or matrix leak needs further investigation. Regardless of this, the increased proton leak/uncoupling along with limited cell death by fission inhibition is likely the underlying mechanism by which decreasing mitochondrial fission provides protection against oxidative tissue damage in diabetic pathology (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of mitochondrial fission protects the cardiac cell under early and late stages of diabetes progression. The formation of short and small mitochondria in metabolic excess is an early event associated with ROS increase. Cumulative oxidative insult causes mitochondrial dysfunction and pathological fragmentation/swelling of mitochondria, leading to further oxidative injury. Imposing suppression of mitochondrial fission at an early stage of progression eliminates mitochondrial shortening and ROS increase. At later stages of progression, fission inhibition would also be protective by preventing an increase in cell death. Accordingly, the inhibition of fission or targeted elongation of mitochondria in cells challenged with excess substrate would reduce oxidative tissue injury. HF, high fat; HG, high glucose.

Perspectives

Mitochondrial morphologic change has been lately recognized as an integral factor in the energetic efficiency of mitochondria to maintain cellular homeostasis. As such, dysregulation of mitochondrial morphological plasticity has been hypothesized to contribute to the progression of metabolic diseases, including diabetic complications, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and DCM (59, 62). Disrupted mitochondrial morphology and energetic dysfunction have long been associated with the pathology of these diseases with the persistent question of where mitochondrial morphologic change resides in their chronological progression.

The relevance of mitochondrial morphologic change in cardiac tissue itself was dismissed until recently because of its rigid architecture assumed to be nonpermissive for such organelle plasticity. The finding that mitochondrial morphologic change is integral to cardiomyocyte differentiation (89), concurrent with the bioenergetic switch to oxidative phosphorylation (32) and the structural maturation of the heart (77), supports the importance of mitochondrial morphology in structural and functional development of the heart. In the adult myocardium, a role for mitochondrial fusion in the complementation of mitochondrial energetic function has now also been established (29).

The role of mitochondrial fission supporting enhanced ROS production in hyper-glycemic/lipidemic flux likely feeds into a vicious cycle in DCM (Fig. 2). The cumulative evidence from murine models and human samples supports this hypothesis with mitochondrial dysfunction and morphologic disruption occurring during the disease progression, in an apparently interdependent way despite a yet inconclusive temporal relationship. Defining the pathologic transition of the vicious cycle, preceding the appearance of dysfunctional mitochondria with reduced membrane potential, will be critical to determining the effective therapeutic window for treatment related with mitochondrial morphologic intervention. The suppression of mitochondrial fission has proved effective in limiting ROS production and oxidative stress under increased metabolic flux (Fig. 6), hence showing promise in the treatment of persistent metabolic stress in a type 1 diabetic animal model (60) and high fat-induced NAFLD (59). The therapeutic value of decreasing mitochondrial fission is, however, questionable considering its requirement of ROS-stimulated mitophagy that eliminates dysfunctional mitochondria (55). This is another example of the mantra necessary in therapeutic applications, “too much of a good thing can be bad.” The aforementioned studies likely avoided this caveat through modest inhibition of fission, which exerts its protective effect through mild proton leak without completely eliminating mitochondrial fission (Fig. 7). Whether targeting mitochondrial morphology is an effective strategy in the treatment of DCM remains to be seen. The pursuit of such studies will further our understanding of the role of mitochondrial morphogenic process in energetic dysfunction, likely offering new therapeutic approaches.

FIG. 7.

Controlling the extent of fission inhibition can modulate ROS and oxidative stress while maintaining mitochondrial function. Sufficiently weak inhibition of mitochondrial fission would induce mild uncoupling without compromising mitochondrial function while relieving the ROS-induced oxidative stress. By this means, mitochondrial morphology could serve as a controlling factor of mitochondrial function. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Abbreviations Used

- 3-NP

3-Nitropropionic acid

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- Cdk

cyclin dependent kinase

- CPT1

carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1

- DCM

diabetic cardiomyopathy

- DKO

double knockout

- DLP1

dynamin-like protein 1

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ESC

embryonic stem cells

- ETC

electron transport chain

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- HR

heptad repeat

- IFM

interfibrillar mitochondria

- IR

ischemia reperfusion

- KO

knockout

- MARF

mitochondrial assembly regulatory factor

- Mff

mitochondrial fission factor

- Mfn

mitofusin

- miR

microRNA

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- O-GlcNAc

O-linked N-acetylglucosamine

- OPA1

optic atrophy 1

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PT

permeability transition

- RCR

respiratory control ratio

- ROCK1

rho-associated kinase 1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- SSM

subsarcolemmal mitochondria

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- UCP

uncoupling protein

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK061991 to Y.Y. and the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 12POST9430003 and Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Rochester discretionary funds to C.A.G.

References

- 1.Amchenkova AA, Bakeeva LE, Chentsov YS, Skulachev VP, and Zorov DB. Coupling membranes as energy-transmitting cables. I. Filamentous mitochondria in fibroblasts and mitochondrial clusters in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol 107: 481–495, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand R, Wai T, Baker MJ, Kladt N, Schauss AC, Rugarli E, and Langer T. The i-AAA protease YME1L and OMA1 cleave OPA1 to balance mitochondrial fusion and fission. J Cell Biol 204: 919–929, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EJ, Kypson AP, Rodriguez E, Anderson CA, Lehr EJ, and Neufer PD. Substrate-specific derangements in mitochondrial metabolism and redox balance in the atrium of the type 2 diabetic human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 1891–1898, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson EJ, Rodriguez E, Anderson CA, Thayne K, Chitwood WR, and Kypson AP. Increased propensity for cell death in diabetic human heart is mediated by mitochondrial-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H118–H124, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Marban E, O'Rourke B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 278: 44735–44744, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aon MA, Stanley BA, Sivakumaran V, Kembro JM, O'Rourke B, Paolocci N, and Cortassa S. Glutathione/thioredoxin systems modulate mitochondrial H2O2 emission: an experimental-computational study. J Gen Physiol 139: 479–491, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashrafian H, Docherty L, Leo V, Towlson C, Neilan M, Steeples V, Lygate CA, Hough T, Townsend S, Williams D, Wells S, Norris D, Glyn-Jones S, Land J, Barbaric I, Lalanne Z, Denny P, Szumska D, Bhattacharya S, Griffin JL, Hargreaves I, Fernandez-Fuentes N, Cheeseman M, Watkins H, and Dear TN. A mutation in the mitochondrial fission gene Dnm1l leads to cardiomyopathy. PLoS Genet 6: e1001000, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Croston TL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Lewis SE, Schnell DM, and Hollander JM. Reversal of mitochondrial proteomic loss in Type 1 diabetic heart with overexpression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R553–R565, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Croston TL, Thapa D, Powell MJ, Razunguzwa TT, and Hollander JM. Proteomic alterations of distinct mitochondrial subpopulations in the type 1 diabetic heart: contribution of protein import dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R186–R200, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer M, Seyfarth T, Sandstede J, Landschutz W, Lipke C, Kostler H, von Kienlin M, Harre K, Hahn D, and Neubauer S. Absolute concentrations of high-energy phosphate metabolites in normal, hypertrophied, and failing human myocardium measured noninvasively with (31)P-SLOOP magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 1267–1274, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belke DD, Larsen TS, Gibbs EM, and Severson DL. Altered metabolism causes cardiac dysfunction in perfused hearts from diabetic (db/db) mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E1104–E1113, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benard G, Bellance N, James D, Parrone P, Fernandez H, Letellier T, and Rossignol R. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and structural network organization. J Cell Sci 120: 838–848, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodrova ME, Dedukhova VI, Mokhova EN, and Skulachev VP. Membrane potential generation coupled to oxidation of external NADH in liver mitochondria. FEBS Lett 435: 269–274, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudina S, Sena S, O'Neill BT, Tathireddy P, Young ME, and Abel ED. Reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and increased mitochondrial uncoupling impair myocardial energetics in obesity. Circulation 112: 2686–2695, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boudina S, Sena S, Theobald H, Sheng X, Wright JJ, Hu XX, Aziz S, Johnson JI, Bugger H, Zaha VG, and Abel ED. Mitochondrial energetics in the heart in obesity-related diabetes: direct evidence for increased uncoupled respiration and activation of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 56: 2457–2466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braschi E, Zunino R, and McBride HM. MAPL is a new mitochondrial SUMO E3 ligase that regulates mitochondrial fission. EMBO Rep 10: 748–754, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan J, Mazumder PK, Hu P, Chakrabarti G, Roberts MW, Yun UJ, Cooksey RC, Litwin SE, and Abel ED. Reduced cardiac efficiency and altered substrate metabolism precedes the onset of hyperglycemia and contractile dysfunction in two mouse models of insulin resistance and obesity. Endocrinology 146: 5341–5349, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckman JF. and Reynolds IJ. Spontaneous changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured neurons. J Neurosci 21: 5054–5065, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bugger H. and Abel ED. Rodent models of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Dis Model Mech 2: 454–466, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugger H, Chen D, Riehle C, Soto J, Theobald HA, Hu XX, Ganesan B, Weimer BC, and Abel ED. Tissue-specific remodeling of the mitochondrial proteome in type 1 diabetic akita mice. Diabetes 58: 1986–1997, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carneiro L, Allard C, Guissard C, Fioramonti X, Tourrel-Cuzin C, Bailbe D, Barreau C, Offer G, Nedelec E, Salin B, Rigoulet M, Belenguer P, Penicaud L, and Leloup C. Importance of mitochondrial dynamin-related protein 1 in hypothalamic glucose sensitivity in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 433–444, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, and Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 15803–15808, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet 46: 265–287, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang CR. and Blackstone C. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Drp1 regulates its GTPase activity and mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem 282: 21583–21587, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CR, Manlandro CM, Arnoult D, Stadler J, Posey AE, Hill RB, and Blackstone C. A lethal de novo mutation in the middle domain of the dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 impairs higher order assembly and mitochondrial division. J Biol Chem 285: 32494–32503, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H. and Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics—fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy—in neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet 18: R169–R176, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, and Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol 160: 189–200, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Csordas G, Jowdy C, Schneider TG, Csordas N, Wang W, Liu Y, Kohlhaas M, Meiser M, Bergem S, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW, 2nd, and Maack C. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ Res 111: 863–875, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 109: 1327–1331, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, and Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science 324: 102–105, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christoffersen C, Bollano E, Lindegaard ML, Bartels ED, Goetze JP, Andersen CB, and Nielsen LB. Cardiac lipid accumulation associated with diastolic dysfunction in obese mice. Endocrinology 144: 3483–3490, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, and Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 4 Suppl 1: S60–S67, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, and Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 15927–15932, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cortassa S, O'Rourke B, and Aon MA. Redox-optimized ROS balance and the relationship between mitochondrial respiration and ROS. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837: 287–295, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cribbs JT. and Strack S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep 8: 939–944, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croston TL, Thapa D, Holden AA, Tveter KJ, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Long DM, Olfert IM, Jagannathan R, and Hollander JM. Functional deficiencies of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in the type 2 diabetic human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H54–H65, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Williamson CL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Frisbee JC, and Hollander JM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart is associated with alterations in spatially distinct mitochondrial proteomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H529–H540, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Bukowski VC, Chapman RS, Leonard SS, Peer CJ, Callery PS, and Hollander JM. Diabetic cardiomyopathy-associated dysfunction in spatially distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H359–H369, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies VJ, Hollins AJ, Piechota MJ, Yip W, Davies JR, White KE, Nicols PP, Boulton ME, and Votruba M. Opa1 deficiency in a mouse model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy impairs mitochondrial morphology, optic nerve structure and visual function. Hum Mol Genet 16: 1307–1318, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Brito OM. and Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 456: 605–610, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Giorgi F, Lartigue L, and Ichas F. Electrical coupling and plasticity of the mitochondrial network. Cell Calcium 28: 365–370, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Vos KJ, Allan VJ, Grierson AJ, and Sheetz MP. Mitochondrial function and actin regulate dynamin-related protein 1-dependent mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol 15: 678–683, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diaz G, Falchi AM, Gremo F, Isola R, and Diana A. Homogeneous longitudinal profiles and synchronous fluctuations of mitochondrial transmembrane potential. FEBS Lett 475: 218–224, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong F, Zhang X, Yang X, Esberg LB, Yang H, Zhang Z, Culver B, and Ren J. Impaired cardiac contractile function in ventricular myocytes from leptin-deficient ob/ob obese mice. J Endocrinol 188: 25–36, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorn GW, 2nd, Clark CF, Eschenbacher WH, Kang MY, Engelhard JT, Warner SJ, Matkovich SJ, and Jowdy CC. MARF and Opa1 control mitochondrial and cardiac function in Drosophila. Circ Res 108: 12–17, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duchen MR, Leyssens A, and Crompton M. Transient mitochondrial depolarizations reflect focal sarcoplasmic reticular calcium release in single rat cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol 142: 975–988, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duvezin-Caubet S, Jagasia R, Wagener J, Hofmann S, Trifunovic A, Hansson A, Chomyn A, Bauer MF, Attardi G, Larsson NG, Neupert W, and Reichert AS. Proteolytic processing of OPA1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to alterations in mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem 281: 37972–37979, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ehses S, Raschke I, Mancuso G, Bernacchia A, Geimer S, Tondera D, Martinou JC, Westermann B, Rugarli EI, and Langer T. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J Cell Biol 187: 1023–1036, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eitel K, Staiger H, Brendel MD, Brandhorst D, Bretzel RG, Haring HU, and Kellerer M. Different role of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in beta-cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 299: 853–856, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eschenbacher WH, Song M, Chen Y, Bhandari P, Zhao P, Jowdy CC, Engelhard JT, Dorn GW., 2nd Two rare human mitofusin 2 mutations alter mitochondrial dynamics and induce retinal and cardiac pathology in Drosophila. PLoS One 7: e44296, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Estaquier J. and Arnoult D. Inhibiting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission selectively prevents the release of cytochrome c during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 14: 1086–1094, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eura Y, Ishihara N, Oka T, and Mihara K. Identification of a novel protein that regulates mitochondrial fusion by modulating mitofusin (Mfn) protein function. J Cell Sci 119: 4913–4925, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, Burgart LJ, and Gores GJ. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology 40: 185–194, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Figueroa-Romero C, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Stadler J, Chang CR, Arnoult D, Keller PJ, Hong Y, Blackstone C, and Feldman EL. SUMOylation of the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 occurs at multiple nonconsensus sites within the B domain and is linked to its activity cycle. FASEB J 23: 3917–3927, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frank M, Duvezin-Caubet S, Koob S, Occhipinti A, Jagasia R, Petcherski A, Ruonala MO, Priault M, Salin B, and Reichert AS. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 2297–2310, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]