Abstract

More than 40,000 patients are diagnosed with head and neck cancers annually in the United States with the vast majority receiving radiation therapy. Salivary glands are irreparably damaged by radiation therapy resulting in xerostomia, which severely affects patient quality of life. Cell-based therapies have shown some promise in mouse models of radiation-induced xerostomia, but they suffer from insufficient and inconsistent gland regeneration and accompanying secretory function. To aid in the development of regenerative therapies, poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels were investigated for the encapsulation of primary submandibular gland (SMG) cells for tissue engineering applications. Different methods of hydrogel formation and cell preparation were examined to identify cytocompatible encapsulation conditions for SMG cells. Cell viability was much higher after thiol-ene polymerizations compared with conventional methacrylate polymerizations due to reduced membrane peroxidation and intracellular reactive oxygen species formation. In addition, the formation of multicellular microspheres before encapsulation maximized cell–cell contacts and increased viability of SMG cells over 14-day culture periods. Thiol-ene hydrogel-encapsulated microspheres also promoted SMG proliferation. Lineage tracing was employed to determine the cellular composition of hydrogel-encapsulated microspheres using markers for acinar (Mist1) and duct (Keratin5) cells. Our findings indicate that both acinar and duct cell phenotypes are present throughout the 14 day culture period. However, the acinar:duct cell ratios are reduced over time, likely due to duct cell proliferation. Altogether, permissive encapsulation methods for primary SMG cells have been identified that promote cell viability, proliferation, and maintenance of differentiated salivary gland cell phenotypes, which allows for translation of this approach for salivary gland tissue engineering applications.

Introduction

Every year, more than 40,000 patients are diagnosed with head and neck cancers in the United States. Many receive radiation therapy, which leads to irreparable damage of the salivary glands, resulting in a permanent dry mouth, a condition known as xerostomia.1 Xerostomia can negatively affect speech, diet, and oral hygiene. Current treatments for xerostomia attempt to lubricate the mouth with artificial saliva or via pharmacological stimulation of residual tissue to increase salivary production. However, no current treatment can fully restore or emulate the myriad functions of the salivary gland, leading to oral health deficiencies.1,2

The salivary gland is composed of two major cell types: acinar cells that initiate salivary secretion and duct cells that propel and modify the ionic components of the secretions.3 Although the salivary gland does not regenerate after radiation damage, it exhibits regenerative potential after mild insults. For example, in a rodent model of salivary gland injury, ligation of the excretory duct results in atrophy of the acinar cells. After removal of the ligation, both the submandibular and parotid glands have restored acinar structures, which supports some inherent but limited gland regeneration.4–6 No salivary gland stem cell has been definitively identified as contributing to gland regeneration; however, several duct cell subtypes have been characterized as progenitor cells.7–12 Furthermore, although the direct injection of progenitor cell populations, namely c-Kit+ salivary progenitor cells10,13 or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs),14 into irradiated submandibular glands (SMGs) showed some functional improvement, restoration of saliva secretion was incomplete, and highly variable.13

To reproducibly promote regeneration and functional recovery of irradiated salivary glands, biomaterial-based approaches for cell transplantation have been explored. Numerous studies have focused on feasibility of using nanofibers or hydrogel-based scaffolds.15–25 Although a few studies have translated their findings in vivo,16,17,23 no study to date has demonstrated that the tissue developed on or within biomaterials contributes to restoration of gland function. To overcome these limitations, we propose use of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels for salivary gland cell transplantation. Unlike hydrogels derived from natural materials (e.g., collagen, fibrin, and hyaluronic acid), PEG hydrogels are inert due to their highly hydrated and uncharged structure, providing a “blank slate” for introduction of growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins or mimetics to control cell behavior.26 Furthermore, the stiffness, degradability, and mesh size (typically between 10 and 30 nm) of PEG hydrogels can be controlled by the composition and relative amounts of PEG macromers.27

PEG hydrogels are traditionally formed through radical-mediated photopolymerizations,28,29 which allow for rapid fabrication into geometries dictated by custom molds in vitro or to match tissue defects in vivo.30,31 PEG hydrogels have been utilized successfully to culture and control the behavior of various cell types, including MSCs,32,33 chondrocytes,34–36 osteoblasts,37 pancreatic β-islet cells,38,39 and neurons.40,41 In addition, recent work has demonstrated the ability of PEG hydrogels to provide spatiotemporal control of MSC delivery in vivo to promote bone regeneration.31,42,43

In this work, methods have been explored to encapsulate, culture, and characterize primary SMG cells within PEG hydrogels, with the long-term goal of developing a tissue engineering approach for the salivary gland. Due to the sensitivity of salivary gland cells to reactive oxygen species (ROS),44–48 we examined the effects of two forms of radical-mediated hydrogel polymerization: chain addition methacrylate-based polymerizations and step-growth thiol-ene polymerizations on primary SMG cells. PEG hydrogels are bioinert,26 and they lack cell–matrix and cell–cell interactions that are commonly utilized to maintain survivability of sensitive cell types.32,38,41,49,50 As cell–cell interactions, in particular, play a vital role in salivary gland cell functions in vitro and during gland development,20,51–57 we also explored the use of SMG cell aggregation into microspheres to increase long-term viability of hydrogel-encapsulated SMG cells. Finally, we examined the cellular composition and proliferative potential of the encapsulated SMG microspheres. Overall, this work demonstrates that PEG hydrogels provide an approach to culture and expand primary SMG cells in vitro for use in salivary gland regenerative therapies.

Methods

Hydrogel macromer synthesis

Materials

PEG-monomethacrylate (PEGMM, 2 kDa, Fig. 1A) and dithiol-functionalized PEG (3.4 kDa, Fig. 3A[i]) were purchased from Dajac Labs and Laysan Bio, respectively. Unfunctionalized PEG (10 kDa) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Four-arm PEG (20 kDa) was purchased from Jenkem Technologies. Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) was synthesized as described.58

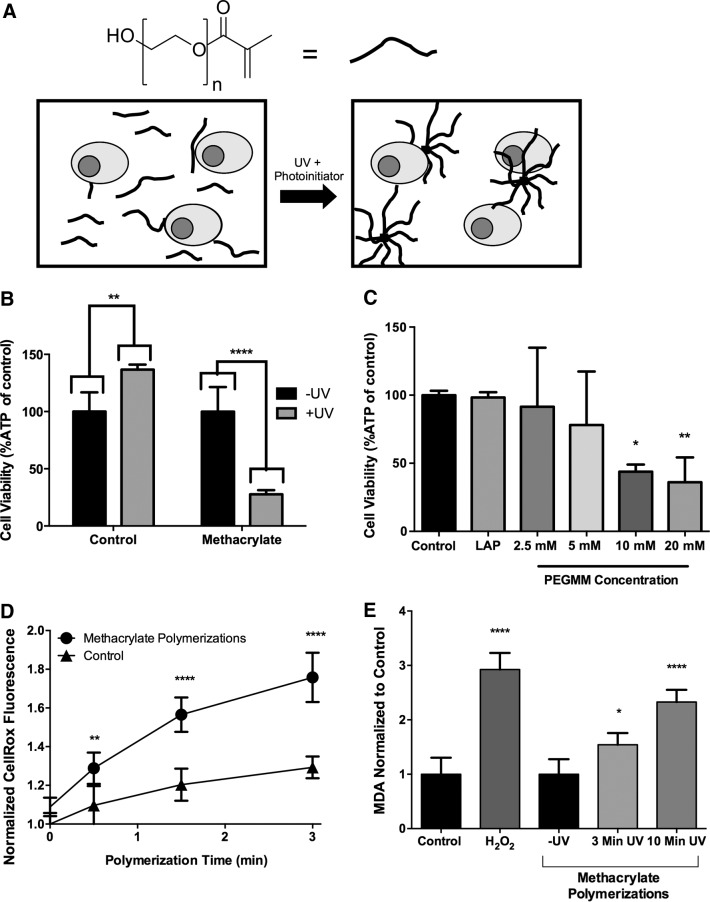

FIG. 1.

Nongelling chain polymerizations using poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-monomethacrylate (PEGMM) result in decreased submandibular gland (SMG) cell viability and increased reactive oxygen species. (A) PEGMM (n=44) is dissolved in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with the photoinitiator and primary SMG cells. Due to the monofunctionality of PEG, aggregates of macromers are formed rather than hydrogels. Illustration is not to scale. (B) Cellular ATP levels of SMG exposed to nongelling polymerizations (SMG cells+lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate [LAP]+20 mM PEGMM). ATP levels are expressed as a % of non UV-exposed SMG cell controls. (C) Cellular ATP levels of SMG cells in the presence of decreasing amounts of PEGMM with LAP after exposure to UV light. ATP levels are expressed as % of ATP in SMG cells in PBS. (D) Measurement of intracellular oxidative stress using CellROX normalized to levels at time 0, and comparing cells exposed to methacrylate with untreated cells. (E) Lipid peroxidation measured via analysis of malonyldialdehyde (MDA) concentration in lysates of SMG cells exposed to methacrylate nongelling polymerization conditions. All methacrylate MDA values were normalized to cells exposed to photoinitiator and macromers but not to UV, while cells treated with 2 mM H2O2 were normalized to untreated cells in PBS. Error bars represent±standard deviation. N=3–8 polymerizations per treatment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 compared with non-UV-exposed samples (B, E) or Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (C, D), determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak posthoc analysis (B) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis.

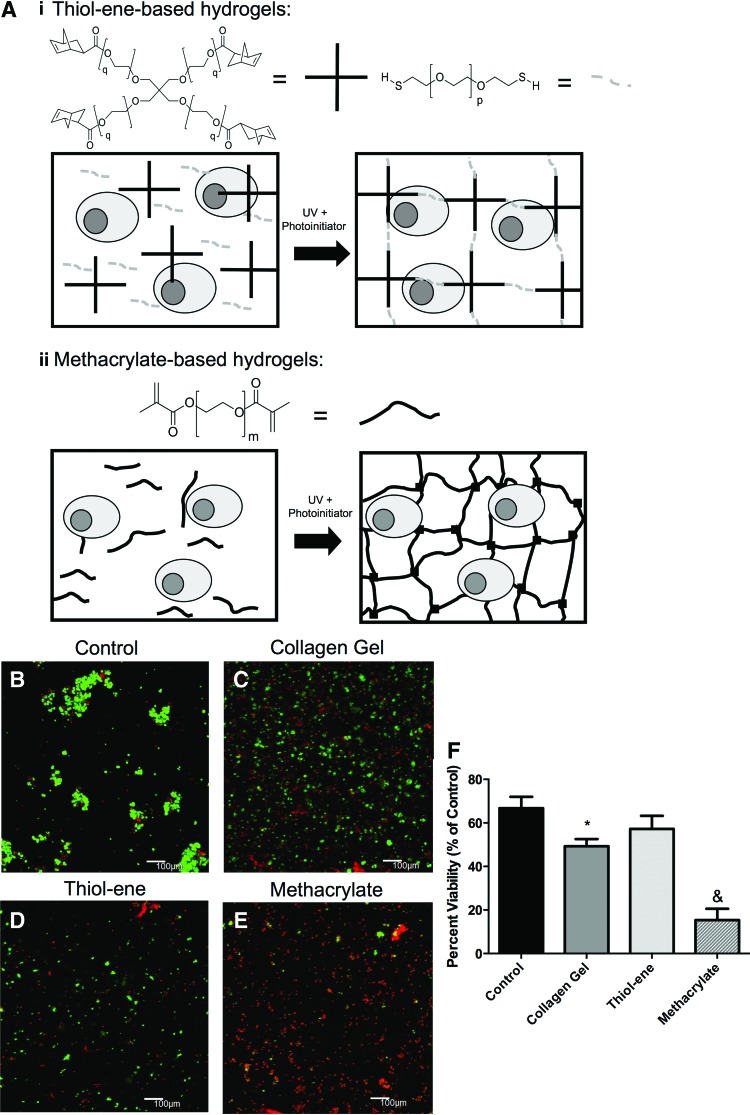

FIG. 3.

SMG encapsulation using step-growth thiol-ene photopolymerization maintains high cell viability. (A) Schematic representation of gelling PEG hydrogel polymerization, illustrations are not to scale. Thiol-ene macromers (i) consisting of four-arm PEG norbornene (q=113, left) and two-arm PEG-dithiol (p=74, right) or methacrylate macromers (ii) consisting of PEG-dimethacrylate were dissolved in DPBS with primary SMG cells and polymerized to form the hydrogel network. Representative 100 μm z-stacks at 100× magnification (living cells=green, dead cells=red) of control, un-encapsulated SMG cells (B), SMG cells encapsulated in collagen gels (C), SMG cells encapsulated in step-growth thiol-ene gels (D), and SMG cells encapsulated in methacrylate-based chain addition gels (E). Quantification of cell viability is expressed as a percentage of living cells divided by total cell number (F). N=3–6, *p<0.05 compared with untreated control cells, &p<0.05 compared with all samples determined using one-way ANOVA Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Dimethacrylate-functionalized PEG synthesis

Linear dimethacrylate-functionalized PEG macromers (PEGDM, Fig. 3A[ii]) were synthesized according to previously established protocols.28,59,60 Briefly, 5 g of linear 10 kDa PEG was methacrylated with methacrylic anhydride (Alfa Aesar, 5 molar equivalents [meq] per PEG hydroxyl) in a commercially available microwave (120 VAC, 12 A; Sharp Carousel). Solutions of PEG and methacrylic anhydride were microwaved for 5 min, pausing every 30 s to vortex samples. PEGDM was dissolved into dichloromethane (DCM, ∼50 mL) in a round bottom flask and precipitated in ∼1 L ice-cold diethyl ether.

Precipitated product was collected on filter paper using vacuum filtration and dried under vacuum for 24 h. Percent methacrylation (>90%) was verified through 1H-NMR using a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer (1H NMR [CDCl3]: 3.5–3.7) (ether protons of PEG, 909H, multiplet), 5.5 (methacrylate vinyl protons, 2H, singlet), 6.2 (terminal vinyl protons, 2H, singlet), and 1.9 (terminal methyl protons, 6H, multiplet).

Norbornene-functionalized PEG synthesis

Four-arm 20 kDa PEG was functionalized with norboronene (PEG-NORB, Fig. 2A) using N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling as previously described.29 Briefly, norbornene carboxylate (10 meq per PEG hydroxyl), DCC (5 meq per PEG hydroxyl), pyridine (1 meq per PEG hydroxyl), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 0.5 meq per PEG hydroxyl) were dissolved in ∼100 mL DCM at room temperature for ∼30 min until a white precipitate (dicyclohexylurea) formed, which indicated formation of dinorbornene carboxylic acid anhydride. Five grams of four-arm PEG dissolved in ∼50 mL DCM was added drop-wise to the anhydride solution, which was subsequently septa sealed, vented with a needle, and stirred overnight at room temperature.

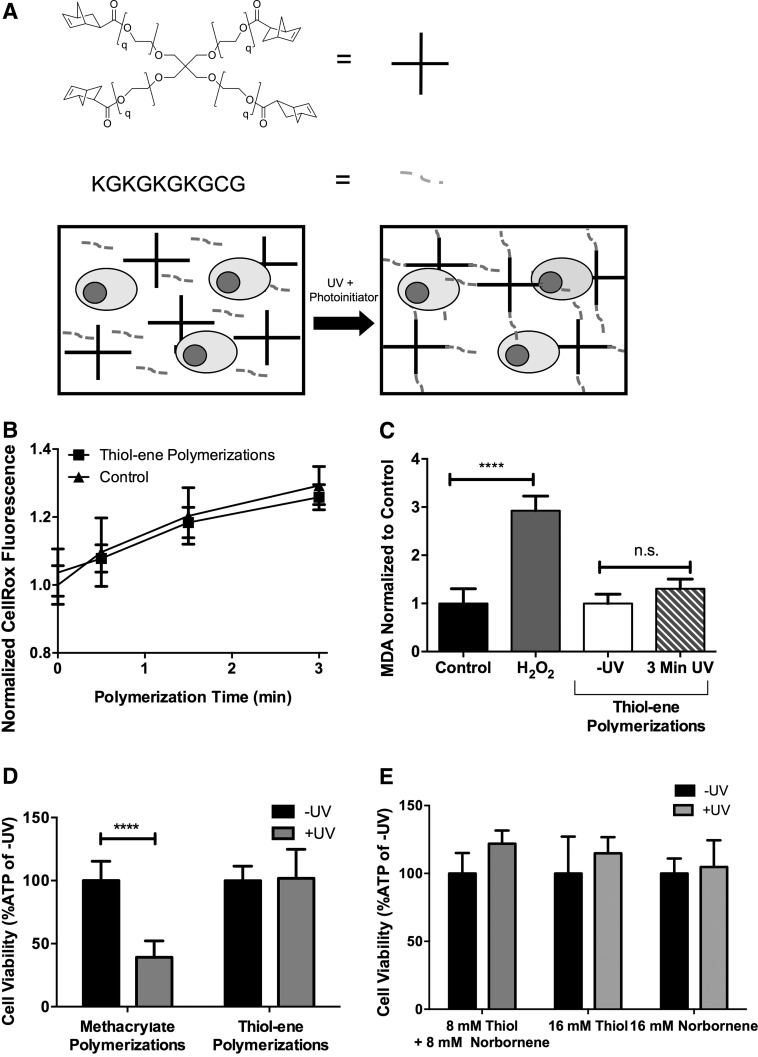

FIG. 2.

Nongelling step-growth thiol-ene polymerization preserves SMG cell viability and reduces oxidative stress. (A) Mono-thiol functionalized peptides (grey dashed lines) participate in radical-mediated polymerization by reacting first with LAP radicals. Resulting thiyl radicals then react with four-arm norbornene-functionalized PEG (PEG-NORB, q=113, black crosses) without forming crosslinks. Circles represent cells, illustration is not to scale. (B) Measurement of intracellular oxidative stress using CellROX normalized to levels at time 0 and comparing cells exposed to thiol-ene with untreated cells. (C) Lipid peroxidation measured via analysis of MDA concentration in lysates of SMG cells exposed to methacrylate and thiol-ene nongelling polymerization conditions. All thiol-ene MDA values were normalized to cells exposed to photoinitiator and macromers but not to UV, while cells treated with 2 mM H2O2 were normalized to untreated cells in PBS. (D) Measurement of cellular ATP levels in cells exposed to either step-growth thiol-ene (10 mM thiol+10 mM norbornene) or methacrylate-based chain addition polymerizations (20 mM methacrylate). (E) Effects of macromer type on the cellular ATP levels of SMG cells exposed to thiol-ene nongelling polymerization conditions. Error bars represent standard deviation. N=8–12 (B), 4 (C, D), and 6 (E). *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak posthoc analysis, n.s.=not significant.

The resulting solution was vacuum filtered and the filtrate was precipitated in 1 L ice-cold diethyl ether, collected by vacuum filtration, redissolved in 75 mL DCM, and reprecipitated two additional times in 1 L ice-cold diethyl ether. Structure and percent functionalization (>90%) was determined by 1H-NMR using a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer (1H NMR [CDCL3]: δ=6.0–6.3 [norbornene vinyl protons, 8H, multiplet]), (3.5–3.9 PEG ether protons, 1817H, multiplet). The final product was dialyzed against distilled, deionized water (ddH2O) for 24 h using 1000 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories) and lyophilized.

Peptide synthesis

The peptide KGKGKGKGCG (Fig. 2A) was synthesized by standard solid-phase peptide synthesis on FMOC-Gly-Wang resin (EMD) using a Liberty 1 Microwave-Assisted Peptide Synthesizer (CEM) with UV monitoring as previously described.61 All amino acids (AAPPTec) were dissolved in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) at 0.2 M. All amino acids were FMOC-protected, with cysteine and lysine side chains protected with trityl and tert-butyloxycarbonyl, respectively. Then, 0.5 M Bezotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (AnaSpec) in dimethylformamide (DMF) was used as activator, 2 M diisopropropylethylamine (Alfa Aesar) in NMP was used as activator base, and 5% piperazine (Alfa Aesar) in DMF was used for deprotection. Peptides were cleaved and deprotected by adding the on-resin 0.25 mmol peptide (0.316 g resin) to a cleavage cocktail composed of 18.5 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, Acros Organic) (Acros Organic), 0.5 mL triisopropylsilane (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5 mL ddH2O, and 0.5 mL 3,6 dioxa-1,8-octane dithiol and mixing for 2 h. Cleaved peptide was separated from resin via vacuum filtration, purified via precipitation in ice-cold diethyl ether (∼180 mL), and collected by centrifugation. The peptide was resuspended in ice-cold diethyl ether, centrifuged twice more, dried under vacuum overnight, dialyzed against ddH2O using 500 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectrum Labs) for 48 h, and lyophilized.

Peptide molecular weight was verified using a Bruker AutoflexIII Smartbeam matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer with 1 mg/mL peptide dissolved in 50:50 acetonitrile:H2O+1% TFA added in a 1:1 volumetric ratio of 10 mg/mL α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Tokyo Chemical Industry) dissolved in 50:50 acetonitrile:H2O+1% TFA. Peptide standards (Bruker Peptide Calibration Standard, 206195) were used for calibration. Peptide purity was analyzed via 205 nm absorbance measured in ddH2O with an Evolution UV/Vis detector (Thermo Scientific) and compared with predicted values using a previously published methodology.62

Cell culture

Isolation and culture of mouse SMG cells

Primary mouse SMG cells were isolated as previously described.8 Briefly, female C57BL/6 mice aged 8–24 weeks were euthanized according to animal protocols approved by the University of Rochester University Committee for Animal Resources. SMGs were surgically removed, finely minced with a razor blade, and dissociated by incubation in 5 mL Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (GIBCO) with CaCl2 and MgCl2, 1 mg/mL collagenase Type II (GIBCO), and 5 μg/mL hyaluronidase (Applichem) at 37°C for 40 min with gentle shaking.

Cells were then washed in 5 mL of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; GIBCO) and with 0.05% Trypsin (GIBCO) for 4 min at room temperature. Cells were passed through 40 μm mesh filters and resuspended in 5 mL complete media (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM):F12 [1:1; GIBCO]) with Glutamax (1×; GIBCO), Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B; GIBCO), N2 supplement (1× Invitrogen), 10 μg/mL insulin (Life Technologies), 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF; Life Technologies), and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Life Technologies). Cells were either immediately prepared for encapsulation or seeded at a density of ∼1.2×106 cells/mL in 60 mm nontissue culture treated petri dishes (5 mL total) and incubated in standard tissue culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) for 48 h to allow microsphere formation.

Analysis of SMG cell function after exposure to nongelling polymerizations

Primary SMG cells were placed in PEGMM (Fig. 1A) to expose them to chain polymerization conditions while avoiding hydrogel formation. Polymerization using mono-functional macromers proceeds similar to a gelling polymerization, but the use of monofunctional rather than difunctional macromers prevents crosslinking and hydrogel formation (Fig. 2A). Similarly, nongelling thiol-ene polymerization was performed with a peptide that incorporates one cysteine group, KGKGKGKGCG (Fig. 2A), which reacts with one norbornene functionality of four-arm norbornene-functionalized PEG (PEGNORB) macromers, precluding crosslink formation (Fig. 2A). Nongelling polymerizations were employed for this subset of studies, because the absence of sol-to-gel transitions reduced potential variability due to diffusional constraints. For experiments directly comparing the effects of thiol-ene or methacrylate polymerization, macromer concentrations were chosen so that the concentrations of reacting functionalities (methacrylate, thiol+norbornene groups) were identical.

Nongelling chain and step-growth polymerizations

Freshly isolated primary SMG cells were resuspended in either 4 wt% PEGMM (20 mM methacrylate groups) or 5 wt% four-arm PEG-norbornene+0.96 wt% of the peptide KGKGKGKGCG (10 mM norbornene groups+10 mM thiol groups). LAP, synthesized as described,58 was used as the photoinitiator at a concentration of 0.028 wt%. Polymerization solutions were pipetted into 1 mL syringe molds and exposed to 3 min of 5 mW/cm2 365 nm light. Polymerizations were also performed using different radical propagating group concentrations (e.g., 20–2.5 mM) in the prepolymerization solution (Figs. 1C and 2E).

SMG cell viability after exposure to nongelling polymerizations

SMG cells were resuspended at 25×106 cells/mL in nongelling polymerization solution, and 45 μL samples (N=3–8) were pipetted into syringe molds. Before polymerizations, 10 μL of cell suspension was removed and diluted in 156 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 1.5 mL tube as the untreated control sample. Dilution was performed to ensure that the concentration of cells was within the linear range of the CellTiterGlo ATP assay from Promega (final cell concentration was ∼80,000 cells per well). After polymerization, 10 μL samples were removed and diluted in 156 μL PBS. One hundred fifty-six microliter of CellTiterGlo reagent mix was added to each sample, which was then distributed into wells of white 96-well plates (100 μL/well in triplicate). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and placed on an orbital shaker for 2 min. Sample luminescence was measured in triplicate on a SynergyMix (BioTek) luminescence plate reader and compared with an ATP standard curve (EMD Millipore) to quantitate sample ATP.

Most primary cell types experience a significant increase in oxygen tension when prepared for primary cell culture,63 which results in an increase in intracellular oxidative stress. Thus, for all measurements of intracellular oxidative stress,64–66 cells were allowed to incubate in suspension culture for 24 h before analysis. To detect intracellular ROS, SMG cells were treated with 5 μM CellRox and 2 μM Calcein AM (Life Technologies) for 30 min, washed with 5 mL DPBS, and resuspended at a concentration of 4.0×106 cells/mL in 50 μL/well aliquots in black 96-well plates. Samples (N=4 for each treatment) were resuspended in either methacrylate (20 mM methacrylate) or thiol-ene (10 mM thiol+10 mM norbornene) nongelling polymerization solution with 0.028 wt% LAP or in DPBS (No Treatment). Samples were exposed to ∼5 mW/cm2 365 nm light for 3 min. Measurements of nongelling polymerization solution CellRox fluorescence (λEx/λEm=630/670 nm) were taken at 0, 0.5, 1.5, and 3.0 min, utilizing equivalent gain at each measurement. CellRox signal was normalized to Calcein AM fluorescence (λEx/λEm 485/530 nm) at time 0 to account for variations in cell number. All measurements were performed using a Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader.

The malonyldialdehyde (MDA; Sigma-Aldrich) assay was used to analyze lipid peroxidation of SMG cells. Primary SMG cells were resuspended at 2.5×107 cells/mL in either thiol-ene or methacrylate nongelling solutions (detailed earlier), DPBS (PBS), or 2 mM hydrogen peroxide (positive control, H2O2) in complete media for 2 h. Samples (55 μL, N=3 [H2O2, PBS], six [all others]) were pipetted into syringe molds. Twenty microliter samples were removed at t=0, 3, and 10 min (methacrylate only) of UV exposure and added to 300 μL of MDA lysis buffer with 3 μL butylated hydroxytoluene. Mixed samples were incubated on ice for 30 min and then gently pipetted to mix and lyse all cells. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min, and 200 μL of each was added to 600 μL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) dissolved in 100% acetic acid in 1.5 mL tubes. Fluorescent TBA-MDA adducts formed during 60-min incubation at 95°C and were measured in triplicate in black 96-well plates using a Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader (λEx/λEm 530/560 nm). Fluorescent signal was quantified using standard curves based on provided MDA standards.

Hydrogel encapsulation of primary SMG cells

The viability of SMG cells encapsulated within methacrylate or thiol-ene hydrogels was compared using LIVE/DEAD staining. The concentration of radical generating or propagating species (LAP and methacrylate, norbornene, and thiol, respectively) was minimized to maximize cell viability. However, the number of radical-propagating species was kept constant between the chain addition and step growth polymerizations, similar to described elsewhere.39 Thus, the conditions of 0.028 wt% LAP and 8.4 wt% PEGDM (16.8 mM methacrylate) or 4.2 wt% PEGNORB+1.3 wt% PEG-dithiol (8.4 mM norboronene+8.4 mM thiol) were used as they were the lowest wt% of LAP and macromer (and hence lowest concentration of radical-generating and propagating species) in which hydrogels could be formed reliably. Cell concentrations (107 cells/mL of Primary SMG cells and 5×106 for microspheres) used for encapsulated cell LIVE/DEAD and ATP analysis were lowered to decrease cell debris aggregates, which interfere with image analysis.

Chain addition methacrylate-based PEG hydrogels

For hydrogel encapsulation within methacrylate polymerized systems, SMG cells (107 cells/mL) were resuspended in 8.4 wt% PEGDM dissolved in DPBS. LAP was used as the photoinitiator at a concentration of 0.028 wt%. Cell suspensions (30 μL each) were pipetted into 1 mL syringes with tips removed and polymerized via exposure to 5 mW/cm2 365 nm UV light for 10 min to form cylindrical hydrogels with heights of 2 mm and diameters of 4 mm. Immediately after polymerization, hydrogels were placed in complete media (1 mL/hydrogel) in 24-well plates.

Step growth thiol-ene PEG hydrogels

For thiol-ene encapsulations, primary SMG cells (107 cells/mL) or microspheres (5×106 cells/mL) were resuspended in 4.2 wt% PEGNORB+1.3 wt% PEG-dithiol with 0.028 wt% LAP in DPBS. Thirty microliter of cell suspension was pipetted into 1 mL syringes with tips removed and polymerized via exposure to 5 mW/cm2 365 nm UV light for 3 min, as thiol-ene polymerizations are more rapid than methacrylate polymerizations and undergo complete polymerization in less than 3 min.29 Immediately after polymerization, hydrogels were placed in complete media (1 mL each) in 24-well plates.

Encapsulation of SMG cells within collagen hydrogels

Collagen gels were formed as previously described.67,68 Briefly, liquid collagen type I from rat tail (4 mg/mL; BD Bioscience) was added to 2× DMEM at a 1:1 volumetric ratio on ice. The pH of Collagen/DMEM solution was raised to 7.4 through addition of 0.1 M NaOH in 10 μL aliquots. pH was monitored using pH strips 5 min after addition of each aliquot. Once pH reached 7.4, 1× DMEM was added to dilute the total amount of collagen to 1.0 mg/mL. Primary SMG cells were resuspended at 107 cells/mL and 30 μL of the cell/collagen solution was pipetted into 1 mL syringes with tips removed. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 to allow complete gelation of collagen. Gels were added to complete media (1 mL) in 24-well plates.

Analysis of hydrogel-encapsulated SMG cell viability

After polymerizations, polymerized hydrogels with encapsulated primary SMG cells or microspheres were placed in 1 mL of complete media and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer (Life Technologies) were added directly to the media to a final concentration of 2 and 4 μM, respectively, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 5% CO2. Samples (N=6 [thiol-ene] or 3 [all others]) were placed in glass-bottom microwell dishes (Maktech) and imaged with an FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus).

Three 100 μm z-stacks were taken at three separate locations at bottom of hydrogels at 100× magnification. Each 100 μm z-stack consisted of 10 images separated by 10 μm. The number of living and dead cells was quantified in 100× z-stacks using VisioPharm software. Briefly, cells were categorized as live or dead based on Bayesian classification of the relative amounts of Calcein AM and Ethidium Homodimer staining. In addition, the majority of the cross-sectional area of hydrogels were imaged in singular lower power (40×) 315 μm z-stacks consisting of 12 slices separated by 28.7 μm and the percent within the field of view (FOV) area in the 40×315 μm z-stacks containing living (CalceinAM positive) cells was quantified using ImageJ.

To further quantify viability in thiol-ene hydrogels, encapsulated primary SMG cells or microspheres were cultured for indicated times with media changes every 48 h, and new EGF and FGF were added to complete media stocks every 4 days. LIVE/DEAD analysis, as described earlier, was performed on thiol-ene polymerized hydrogels 4, 7, and 14 days after encapsulation. For whole hydrogel ATP analysis, thiol-ene polymerized hydrogels at indicated timed points were incubated in 500 μL of 50% CellTiterGlo Reagent/50% DPBS for 45 min on an orbital shaker at room temperature. One hundred microliter triplicates were added to a white 96-well plate, and sample luminescence was measured on a SynergyMix (BioTek) luminescence plate reader. ATP was quantified using a standard curve as described in section “SMG cell viability after exposure to nongelling polymerizations”.

Assessment of encapsulated cell lineage

The Mist1CreERT2 mice (Mist1Cre) were produced as described69 and generously donated by Dr. Stephen Konieczny (Purdue University). Mist1CreERT2 mice were mated to the R26tm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze reporter strain, from Jackson Laboratories. Activation of Mist1Cre in the presence of tamoxifen results in genetic labeling of a high proportion of acinar cells by expression of the tomato red reporter gene. Labeling of duct cells was done by crossing the same reporter strain with a transgenic line in which the keratin 5 promoter drives CreER (K5Cre) (Jovov et al.70; donated by Dr. Jianwen Que, University of Rochester). Both strains were maintained on a C57BL/6 background.

Tamoxifen (60 mg/mL dissolved in corn oil) was administered by gavage (0.25 mg/g body weight) on four consecutive days in the week before gland harvest for Mist1Cre mice and 1 day before harvest for K5Cre mice. SMG glands were harvested, cultured as microspheres, and encapsulated as described earlier. Three 100 μm z-stacks were taken at three separate locations at bottom of hydrogels at 100× magnification at day 0, 4, 7, and 14 days postencapsulation. Each 100 μm z-stack consisted of 10 images separated by 10 μm. The percentage of cross-sectional area containing tdTomato-expressing cells within Calcein AM-positive microspheres was quantified using VisioPharm and an in-house developed application. The application quantified the total area circumscribed within Calcein AM expressing microspheres as well as the total area of tdTomato fluorescence using image thresholding. Percentages of Mist1 and K5 cells were calculated by dividing the total area of tdTomato fluorescence by the total microsphere area determined by Calcien AM staining.

Edu labeling of encapsulated microspheres

SMG microspheres were incubated in 10 μM EdU for 3 h and fixed with 1 mL 4.0% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed twice with 1 mL 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in DPBS, and permeabilized with 1 mL of 0.5% of Triton X-100 for 30 min. Samples were then washed twice with 1 mL 3% BSA in DPBS and fluorescently labeled with AlexaFluor 647 using the Click-iT® Plus EdU AlexaFluor® 647 imaging kit (Life Technologies) with Hoescht 33342 as a nuclear counterstain. All samples were imaged with a FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus) at 200× magnification.

Disruption of cell–cell contacts with trypsinization

SMG microspheres were washed with DPBS, resuspended in 2 mL of 0.05% Trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraaceticacid (GIBCO), and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Trypsin was diluted by adding 2 mL of sphere media, and the entire volume was passed through a 40 μm strainer. Trypsinized SMG cells were then pelleted and washed with 5 mL DPBS. Trypsinized SMG cells were encapsulated and characterized as described with both LIVE/DEAD staining and ATP quantification immediately and at 7 days after encapsulation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined with Prism (Version 6.02; Graphpad) using either one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis or two-way ANOVA with Sidak posthoc analysis. All data and error bars are represented as averages and standard deviations.

Results and Discussion

Exposure to methacrylate-based chain addition polymerizations reduced SMG cell viability via increased intracellular ROS mediated by lipid membrane peroxidation

The overarching objective of this work is the eventual use of PEG hydrogels to transplant SMG cells in vivo to restore salivary gland function after irradiation. Therefore, initial experiments focused on identification of hydrogel encapsulation methods that maintain primary SMG cell survivability. Initially, methacrylate-functionalized PEG macromers were used due to their ease of synthesis and successful use with myriad cell types.32–34,37,38,40,71 To screen SMG cytocompatibility, nongelling polymerizations were used to alleviate potential issues with diffusional constraints28,59 by using macromers with only one functionality (Fig. 1A). SMG cells were exposed to the reactions necessary to form hydrogels, including radical generation by cleavage of photoinitiators and propagation through methacrylate-based carbon–carbon double bonds, but not to the sol-to-gel formation consistent with hydrogel formation. Similar experiments have been used to study the effects of hydrogel polymerization on a β-cell line.39

Primary SMG cells were resuspended in PEGMM and the photoinitiator, LAP. Nongelling methacrylate polymerizations in the presence of 20 mM PEGMM+LAP resulted in a ∼70% reduction in viability of primary SMG cells, as assessed by decreased ATP levels (Fig. 1B). Cellular ATP has a rapid turnover (t1/2 ∼ minutes), and dead cells experience a rapid drop in ATP levels,72–74 making ATP an appropriate surrogate analyte for viability.39 Immediately after exposure to chain-addition methacrylate polymerization conditions, SMG cells experienced a significant decrease in viability, suggesting acute cell death (Fig. 1B).

Cell viability exhibited an inverse proportional relationship with PEGMM macromers present within the reaction. Macromer concentrations of 5 mM or less did not result in detectable cytotoxicity (Fig. 1C). Neither LAP alone nor 2.5 mM PEGMM caused decreases in cell viability (Fig. 1C), supporting the idea that polymerization-associated cytotoxicity is directly related to PEGMM macromer concentration. Somewhat surprisingly, exposure to 365 nm light alone significantly increased ATP levels by ∼35%. Although 365 nm light has not previously been found to affect cellular viability,39 we hypothesize that the increase in ATP levels may be related to mixing that increases overall dissolved oxygen in the cell/macromer suspension. Increases in dissolved oxygen have been shown to increase cellular ATP levels, perhaps through increased cellular metabolism.75,76

In contrast to fibroblasts,71 primary osteoblasts,77 primary chondrocytes,34 and human MSCs,32 primary SMG cells exhibit poor viability when exposed to methacrylate-based chain-addition polymerization reactions (Fig. 1B). The SMG cell population is heterogeneous and consists of terminally differentiated cells, many of which undergo apoptosis after isolation.8,10 However, the process of apoptosis takes ∼3 h,78 which is in stark contrast to the ∼60–80% of SMG cell death observed after only minutes of exposure to chain-addition polymerizations (Fig. 1B). We speculated that ROS produced by the interference of oxygen during the methacrylate polymerization process79 may cause the polymerization-associated cell death. To investigate the link between increased intracellular oxidative stress and PEG macromer polymerization conditions, the commercially available CellROX dye (Life Technologies) was used to measure intracellular oxidative stress. Lipid peroxidation was also analyzed indirectly by measuring MDA accumulation (MDA; Sigma), as MDA is a product of unsaturated lipid degradation by ROS. Increases in MDA suggest peroxidation of plasma membranes,80,81 which can also lead to increases in intracellular oxidative stress.19,36

SMG cells underwent a significant 1.7-fold increase in intracellular oxidative stress compared with SMG cells in DPBS (Fig. 1D). Cells in PBS exposed to UV experience a 1.2-fold increase in intracellular ROS, which suggests that exposure to UV alone causes some increase in intracellular ROS (Fig. 1D). In addition, SMG cells exposed to 3 and 10 min of methacrylate-based polymerizations exhibited statistically significant increases (∼1.5- and ∼2.2-fold, respectively) in MDA levels compared with untreated cells (Fig. 1E). The increase in MDA was similar to SMG cells treated with H2O2 as a positive control. As MDA is a byproduct of membrane peroxidation,80,81 the increases suggest that methacrylate-based polymerization causes membrane peroxidation. The increased levels of intracellular ROS (Fig. 1D) also support membrane peroxidation, as it is unlikely that the photoinitiator LAP, which exists as a salt,58 or the large PEG macromers could cross the cell membrane to directly generate ROS intracellularly.

A rise in oxidative stress associated with membrane oxidation has also been observed for primary chondrocytes encapsulated within methacrylate-based hydrogels.36 The salivary gland has long been known to exhibit a paradoxically acute sensitivity to radiation therapy.47,82,83 The loss of terminally differentiated secretory cells after radiation has been suggested to occur through radical-mediated damage of secretory granules84 or the plasma membrane.44 A process common to both of these phenomena is the formation of hydroxyl radicals from the irradiation of water, which subsequently abstracts hydrogens from unsaturated fatty acids in the plasma membrane and generates peroxyl radicals that propagate through adjacent fatty acids molecules, resulting in membrane destabilization.46 We believe that primary SMG cells are exhibiting a similar sensitivity to ROS here and hypothesize that ROS generated by methacrylate-based chain addition polymerizations damage the SMG cell membrane lipids, leading to increased intracellular oxidative stress and cell death.

In contrast to MIN-6 cells, a pancreatic β-cell line,39 exposure to photoinitiator alone did not affect viability of primary SMG cells. We speculate that this may be due to differences in the method of cell preparation. MIN-6 cells are trypsinized into single cell suspensions, while SMG cells are enzymatically degraded into small clumps that likely include some residual ECM. Pericellular ECM has been shown to decrease intracellular ROS generated by exposure to UV and activation of photoinitiator.36 Thus, it is possible that SMG cells may be protected in the presence of photoinitiator alone by residual pericellular ECM, but the combination of photoinitiator and methacrylate species raises ROS concentrations to levels that adversely affect SMG cells. Polymerization of (meth)acrylated PEG macromers impairs the diffusion of radical-generating species (e.g., photoinitiator) and exponentially increases local concentrations of radicals, a process known as auto-acceleration.27,85 Increased radical concentrations attributed to auto-acceleration resulted in increases in ROS levels that detrimentally affected PEG hydrogel-encapsulated chondrocytes,36 similar to methacrylate-based polymerization-associated SMG cell death in the studies presented here.

The link between ROS and cell viability was also tested by treating SMG cells with 10 mM of the antioxidant Trolox (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea) for 2 h before exposure to nongelling methacrylate polymerizations. Trolox is an analog of vitamin E, which protects lipid membranes from oxidation and has been shown to reduce ROS-mediated cell death in neurons and cardiomyocytes.86,87 Ten micromolar Trolox treatment was sufficient to rescue cell viability as measured by ATP levels (Supplementary Fig. S1B) after exposure to nongelling methacrylate polymerizations, further suggesting that ROS generated from methacrylate polymerization causes decreased SMG cell viability. However, antioxidant treatment can also scavenge radicals that are required for crosslink formation, thus inhibiting hydrogel formation, as shown by decreased compressive moduli of hydrogels formed in the presence of both 1 and 10 mM Trolox (Supplementary Fig. S1C). In addition, antioxidants may introduce potential dose-dependent pleiotropic effects, further complicating their use.88 We conclude that ROS produced by methacrylate-based PEG polymerization reactions negatively affect SMG cells by increasing lipid peroxidation and intracellular oxidative stress, which subsequently leads to decreased cell viability.

Exposure to thiol-ene polymerizations preserved SMG cell viability by lowering intracellular ROS levels associated with polymerization

Having established a relationship between chain-addition polymerization, increased ROS, and decreased viability of SMG cells, an alternative polymerization method was examined. Thiol-ene polymerizations are known to result in significantly less overall ROS exposure due to the rapid consumption of generated ROS by free thiol groups.79 Furthermore, PEG hydrogels formed using step-growth, thiol-ene polymerizations have excellent cytocompatibility for the encapsulation of ROS-sensitive cell types. For example, MIN-6 cells exhibit high (>90%) viability after encapsulation within thiol-ene hydrogels compared with ∼15% viability when encapsulated within chain-polymerized hydrogels.39

Beyond cytocompatibility, it is important to determine and minimize cellular oxidative stress, as in situ hydrogel polymerizations could have pleiotropic effects on cell fate and function. ROS have been implicated in a variety of processes such as reducing lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells,89 inducing insulin resistance in adipocytes,90 and regulating Notch signaling in epidermal cell differentiation.91 Recent work comparing chain addition and thiol-ene polymerizations for encapsulation of primary chondrocytes shows that increased ROS exposure resulting from chain addition polymerizations leads to hypertrophic chondrocyte phenotypes similar to pathologic chondrocytes observed in osteoarthritis. In contrast, the phenotypes of chondrocytes encapsulated using a thiol-ene polymerization resemble those present in hyaline cartilage.35

To investigate the effects of thiol-ene polymerizations on SMG cell viability, nongelling, thiol-ene polymerizations were performed using four-arm PEG-norbornene and the peptide KGKGKGKGCG (Fig. 2A). The single cysteine residue participates in the polymerization but does not act as a crosslinker for hydrogel formation (Fig. 2A). SMG cells exposed to 3 min of thiol-ene polymerization conditions, which is required to reach 100% conversion,29 exhibited significant changes in neither intracellular oxidative stress (Fig. 2B) nor MDA levels (Fig. 2C) compared with untreated cells. This suggests that SMG cells exposed to thiol-ene polymerization conditions do not suffer from lipid peroxidation and subsequent oxidative stress as opposed to SMG cells exposed to methacrylate polymerization.

In contrast to the ∼60% decrease in cell viability after methacrylate polymerization, SMG cells exposed to thiol-ene polymerization exhibited no measurable losses in viability (Fig. 2D). In addition, SMG cells exposed separately to components of thiol-ene reactions (e.g., 16 mM of thiol or norbornene [ene]) exhibited no losses in viability (Fig. 2E), further demonstrating the cytocompatibility of thiol-ene hydrogel components. We conclude that the alternative use of thiol-ene polymerizations, which results in minimal ROS, is a favorable strategy for the encapsulation of SMG cells.

Results from the nongelling polymerization studies were verified in gelling polymerizations (Fig. 3A). LIVE/DEAD staining of SMG cells encapsulated within PEG hydrogels formed using methacrylate or thiol-ene polymerization was performed immediately after encapsulation. In addition, SMG cells were encapsulated within collagen hydrogels to provide a comparison to hydrogels that do not rely on radical-based reactions. Under standard suspension culture conditions, control SMG cells had viabilities (% of cells expressing LIVE marker out of total number of cells LIVE+DEAD) of ∼66% (Fig. 3B). SMG cells encapsulated in PEGDM exhibited viabilities of ∼15% (Fig. 3E). In contrast, SMG cells encapsulated in thiol-ene gels had viabilities of ∼57% (Fig. 3C), statistically similar to untreated controls (Fig. 3B).

Somewhat surprisingly, SMG cells encapsulated within thiol-ene hydrogels had slightly higher viabilities than those encapsulated in collagen gels, which exhibited viabilities of ∼50% (Fig. 3D). This might be attributed to temperature fluctuations required for collagen hydrogel formation, compounded by 1 h gelation times during which cells are concentrated within a small volume and may experience metabolic stress. Thus, under both nongelling and gelling conditions, the thiol-ene hydrogels provide a suitable environment for SMG cell encapsulation.

Cell–cell interactions are essential for long-term viability of encapsulated SMG cells within thiol-ene polymerized PEG hydrogels

With the identification of a cytocompatible hydrogel polymerization process for SMG cell encapsulation, we next sought to characterize viability over therapeutically relevant time scales. After ductal ligation, SMG gland regeneration occurs within 14 days.6 In addition, in previous transplantation studies using MSCs, hydrogels with an in vivo degradation time of 2 weeks were employed to improve femoral allograft healing.43 Together, these studies supported our choice of 14 days as a therapeutic timeframe over which to maintain viability in vitro. SMG cells were isolated, encapsulated in thiol-ene hydrogels and cell viability was measured using LIVE/DEAD staining (Fig. 4A–D). Results of LIVE/DEAD staining were quantified both as the percentage of cells stained with the LIVE marker out of the total cell (LIVE+DEAD) population and as the percentage of a low power (40×) FOV that is occupied by cells stained with LIVE marker. Measuring the amount of total FOV area occupied by LIVE cells accounts for total changes in cell density of the hydrogel, as only viable cells are analyzed.92 Therefore, we measured both the percentage of living cells, which is accurate for short-term culture, and percentage of FOV area to obtain longitudinal measurements of cell viability.

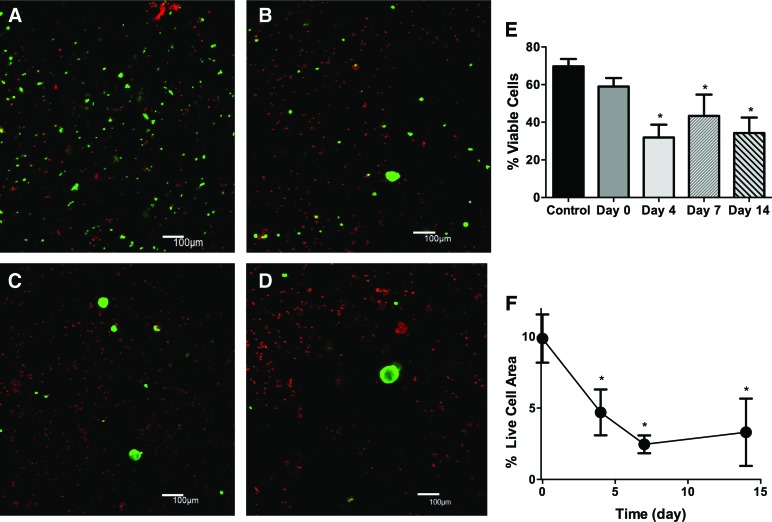

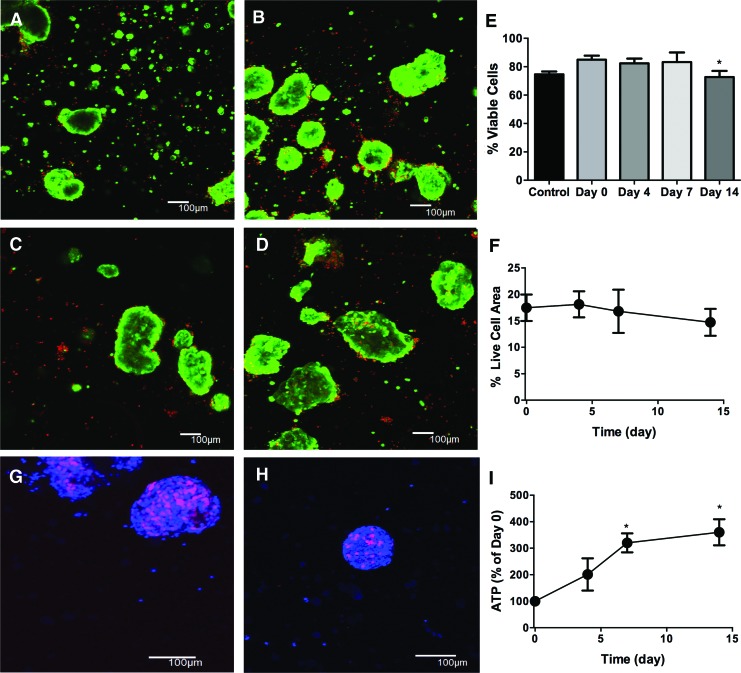

FIG. 4.

Primary SMG cells exhibit poor viability within thiol-ene polymerized PEG hydrogels. Representative 100 μm z-stacks at 100× magnification (living cells=green, dead cells=red) of primary SMG cells at 0 (A), 4 (B), 7 (C), and 14 (D), after encapsulation. (E) Quantification of cell viability from 100× images expressed as a percentage of living cells divided by total cell number. (F) Percentage of 40× field of view that stains positive for living cells. N=3, error bars±standard deviation, *p<0.05, compared with day 0 determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

SMG cells encapsulated within thiol-ene hydrogels showed a significant decrease in the percentage of living cells (from ∼60% to 35%) by day 4, which was consistent from days 4 to 14 postencapsulation (Fig. 4A, B, E). The % of FOV with living cells also decreased substantially from 10% immediately after encapsulation to 5% at 4 days after encapsulation (Fig. 4F). The decrease in total live cells is due to loss of single cells and smaller cell clusters within the first 4 days after encapsulation (Fig. 4B). By 7 and 14 days after encapsulation, spherical clusters of cells ∼50 μm in diameter are the only viable cells observed within gels (Fig. 4C, D). Thus, a substantial proportion of encapsulated SMG cells die during the 14-day culture period, although larger clusters remain viable till day 14 (Fig. 4D).

To counter the loss of single SMG cells after encapsulation, we analyzed cell viability of encapsulated microspheres preformed in suspension culture. After 2–3 days of suspension culture, dissociated SMG cells form microsphere cell clusters (>50 μm in diameter) that include both duct and acinar cells.8,10 The viability of microspheres encapsulated within thiol-ene polymerized PEG hydrogels was analyzed using LIVE/DEAD imaging at days 0, 4, 7, and 14 after encapsulation (Fig. 5A–F) and by measuring whole hydrogel cellular ATP levels (Fig. 5I). The heterogeneity in microsphere size is evident with LIVE/DEAD imaging immediately after encapsulation (Fig. 5A). Over the 14-day culture period, there is a significant increase in microsphere size (Fig. 5B–D).

FIG. 5.

SMG microspheres show high and sustained viability within thiol-ene polymerized PEG hydrogels. Representative 100 μm z-stacks at 100× magnification (living cells=green, dead cells=red) of primary SMG cells at 0 (A), 4 (B), 7 (C), and 14 days (D), after encapsulation. (E) Quantification of cell viability from 100× images expressed as a percentage of living cells divided by total cell number. (F) Percentage of 40× field of view that stains positive for living cells. EdU labeling (Blue=4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Red=EdU) of microspheres at days 3 (G) and 8 after encapsulation (H) to detect cellular proliferation. (I) Quantification of cellular ATP levels at 0, 4, 7, and 14 days after encapsulation. N=3, error bars±std deviation, *p<0.05, compared with day 0 determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

In contrast to the low viability of single cells after encapsulation, the percentage of living cells in microspheres was >70% and comparable to nonencapsulated cells at each time point analyzed (Fig. 5E). Similarly, the FOV area occupied by living cells was ∼17% at day 0 and remained statistically equivalent over 14 days (Fig. 5F). Total cellular ATP also increased ∼3.5-fold over the 14-day culture period, indicating maintenance of SMG cell viability (Fig. 5I). To confirm the presence of proliferating cells within microspheres, EdU labeling was employed.93 Microspheres at both days 3 (Fig. 5G) and 8 (Fig. 5H) included high numbers of EdU-positive cells, consistent with cell proliferation. Together with the increased measure of cellular ATP (Fig. 5I), this result supports the conclusion that encapsulated microspheres contain viable, proliferative cells.

Due to cellular proliferation, it would be expected that increases in cell density would be observed; however, results measuring the percentage of FOV area containing LIVE cells showed no measurable increases for encapsulated spheres. This could be attributable to hydrolytic degradation and subsequent network swelling,94 which would lead to overall decreases in cell density. This phenomenon was observed with human MSCs encapsulated within thiol-ene hydrogels despite exhibiting high viability determined via LIVE/DEAD staining.92 Furthermore, as the mesh size of most PEG hydrogels is several orders of magnitude smaller than cells,27,95,96 the ability of proliferating cell populations to expand throughout the hydrogel is slowed in the absence of cell-based degradability.97 Thus, it is probable that measuring cell density by calculating FOV area occupied by LIVE cells does not fully capture actual overall increases in cell number, as suggested by the whole hydrogel ATP data (Fig. 5I) and EdU staining (Fig. 5G, H).

Cell–cell interactions are essential for in vitro salivary gland cell culture and in vivo gland development. E-cadherin plays an important role in the development of the SMG,51–55 in particular to provide survival signals to maturing duct cells.55 Recent studies have shown that cells dispersed from salivary gland tissues in mice and humans can self-assemble to acinar-like structures in vitro and display characteristics of native gland structures.20,56,57 To investigate whether the increased viability of microspheres within PEG hydrogels is due to increased cell–cell interactions or to an enrichment of more proliferative cells, microspheres were treated with trypsin to form single cell suspensions before encapsulation.

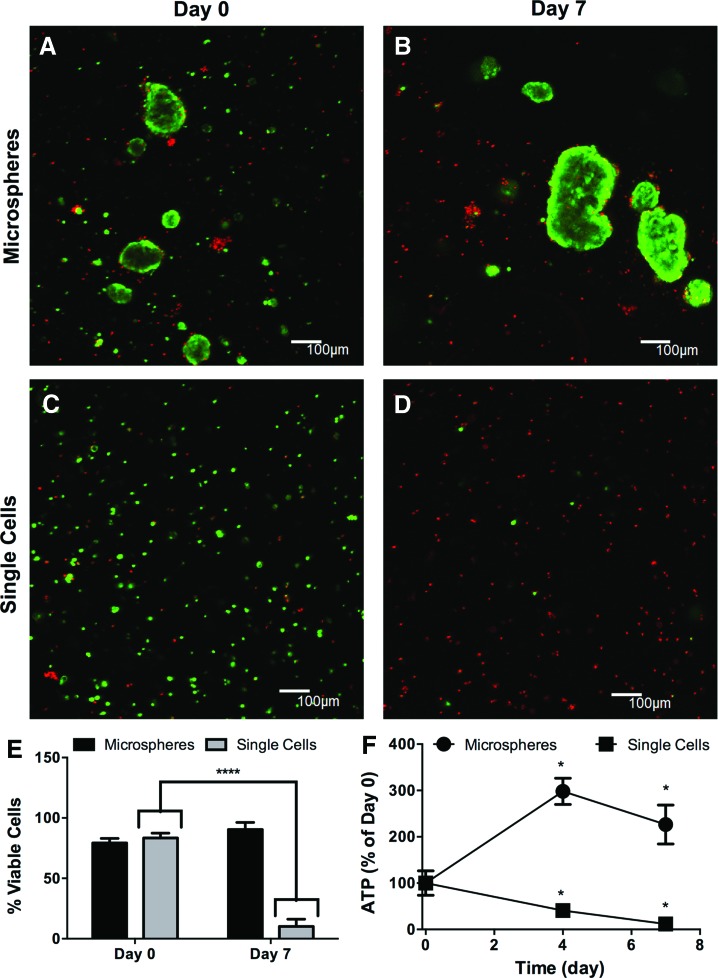

LIVE/DEAD staining showed that both encapsulated microspheres (Fig. 6A) and single cells (Fig. 6C) had comparable viability at day 0, indicating that trypsin treatment did not cause initial cell death. However, after 7 days, the viability of encapsulated single cells (Fig. 6D) decreased from ∼87% to ∼10% (Fig. 6B) while microsphere viability remained at ∼80% through day 7 (Fig. 6E). In concert, cellular ATP levels declined in single cells by 70% from day 0 to 7, but increased ∼250% in microspheres (Fig. 6F). These data support the idea that cell–cell interactions are critical for viability of primary SMG cells, and are in agreement with a previous report showing that cell viability is lost when microspheres are dissociated.10 Preserving cell–cell interactions has been found to promote the viability of other cell types such as pancreatic β-cells and motor neurons when encapsulated within PEG hydrogels,38,41 supporting the rationale for the assembly of these multicellular “microtissues” before encapsulation.

FIG. 6.

Disruption of SMG cell–cell contacts results in cell death. Representative 100 μm z-stacks at 100× magnification (living cells=green, dead cells=red) of SMG microspheres (A, B) or single cells after trypsinization (C, D), immediately and 7 days after encapsulation. (E) Quantification of cell viability from 100× images expressed as a percentage of living cells divided by total cell number. (F) Quantification of cellular ATP levels at 0, 4, 7, and 14 days after encapsulation. N=3(E) 4 (F), error bars±standard deviation, *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 compared to day 0 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD posthoc analysis (F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak posthoc analysis (E). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Encapsulated microspheres display markers of acinar cell lineage

The phenotype of cells within encapsulated microspheres was characterized by immunohistochemistry. Microspheres from suspension culture included cells that expressed both acinar (Supplementary Fig. S2A) and duct cell (Supplementary Fig. S2B) markers, in agreement with previous reports.8,10 To directly track the fate of acinar cells within the hydrogels, a CreLoxP-ROSA26 lineage tracing system was used. In this system, an inducible Cre recombinase has been introduced into the Mist1 gene locus, which encodes a transcription factor specifically expressed in the secretory acinar cells.98 This mouse strain was crossed with the R26 tdTomato reporter strain. Administration of tamoxifen activates the Cre recombinase, which mediates recombination, leading to expression of the tdTomato reporter specifically in acinar cells (Supplementary Fig. S3). Other cell lineages, which can also be labeled with calcein AM, are not tdTomato positive (Supplementary Fig. S2E, F).

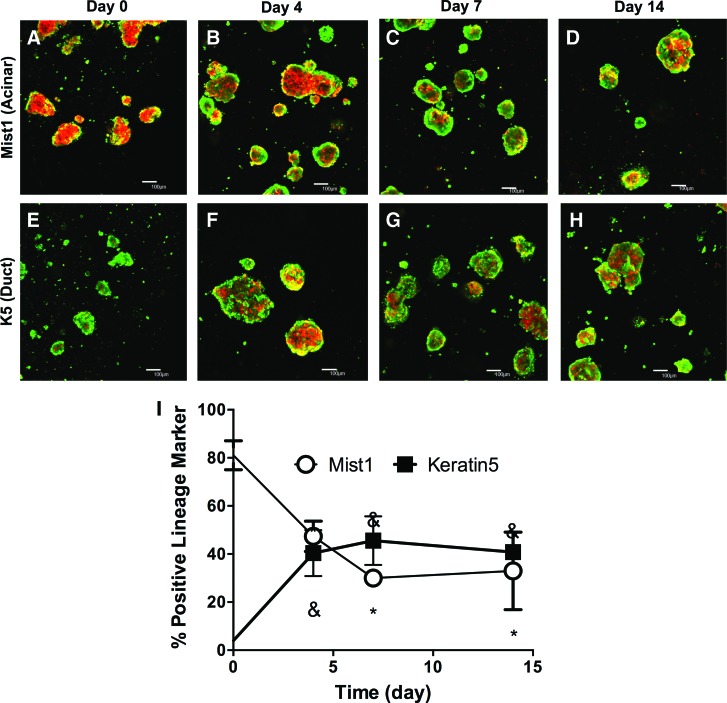

This lineage tracing system was utilized to study the cellular composition of encapsulated microspheres. Directly after encapsulation, a majority of cells were positive for tdTomato, indicating that the encapsulated microspheres comprised acinar cells (Fig. 7A). This is supported by immunofluorescence imaging of microspheres before encapsulation, which show high expression of the serous acinar cell marker, Nkcc1 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). In the encapsulated spheres, the percentage of acinar cells decreased from ∼80% to ∼45% of total cells by day 4 (Figs. 7B and 7I). After 7 and 14 days postencapsulation, the percentage of acinar cells remains stable at 40% (Fig. 7C, D, I), demonstrating that viable acinar cells constitute a significant proportion of cells within encapsulated microspheres.

FIG. 7.

Encapsulated SMG microspheres express markers of both acinar and duct cell lineages. One hundred micrometer z-stacks at 100× magnification of Mist1-Cre/tdTomato microspheres co-labeled with Calcein AM (green=living, red=lineage of Mist1-expressing cells) at 0 (A), 4 (B), 7(C), and 14 (D) days after encapsulation. One hundred micrometer z-stacks at 100× magnification of K5-Cre/tdTomato microspheres co-labeled with Calcein AM (green=living, red=lineage of K5-expressing cells) at 0 (E), 4 (F), 7 (G), and 14 (H) days postencapsulation. (I) Quantification of Mist1-lineage cells and K5-lineage cells. N=3, error bars±standard deviation, *,&p<0.05 compared with day 0 for Mist1 and K5, respectively. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

These data suggest either a decrease in the number of acinar cells or an expansion of nonacinar-derived populations or a combination thereof. To assess alternative lineages that may be present, Keratin5 (K5) lineage tracing was employed. K5-expressing cells, found primarily in the myoepithelium and the ducts, have been shown to have progenitor-like properties during development99 and to participate in gland healing after duct ligation.100 Mice carrying Cre at the K5 gene locus and the R26 tdTomato reporter were injected with tamoxifen before gland harvest. On encapsulation of SMG microspheres, only ∼4% of cells are K5 positive (Fig. 7E). However, the percentage of K5-lineage-labeled cells increased to ∼38% of the total cellular population by 4 days after encapsulation (Fig. 7F) and remained between 30% and 40% of total cells at 7 and 14 days postencapsulation (Fig. 7G, H, I). These data suggest that K5-lineage cells expand significantly within hydrogel-encapsulated SMG microspheres.

Cre-based lineage tracing in microspheres entrapped within PEG hydrogels offers a way to relate the in vivo role of cells to that observed in suspension cultures in vitro. By analyzing Mist1 and K5-positive cells, we were able to describe 70–80% of the total cellular content of microspheres over a 14 day culture period and capture changes in the encapsulated cell populations. Previous studies8,10 have characterized microspheres based on cell morphology and expression of marker proteins, but neither study examined from which lineage the cells originate. As previously mentioned, K5 cells have been shown to have progenitor-like qualities in vivo,99,100 thus partially explaining the substantial increase in K5-lineage-labeled cells observed over the 14 days postencapsulation.

The decrease in the number of Mist1-lineage labeled cells is supported by absence of cells with acinar-like morphology observed 3 days after sphere culture by others.10 In contrast, however, our data show that 30–40% of the total encapsulated cell population comprises Mist1-lineage-labeled cells and remains stable from 7 to 14 days after encapsulation, suggesting that acinar-derived cells form a stable population in vitro. Taken together, these results demonstrate that encapsulated microspheres are composed of both acinar and duct cells. The expansion of the K5-duct cell population supports their role as a progenitor cell population, while the maintenance of the Mist1-acinar cell population shows that acinar cells are involved in the formation of microspheres, which has not been observed in previous studies.8,10 Moreover, this approach provides a direct method for characterizing the cellular composition of SMG microspheres in vitro.

We aim at developing a cell transplantation system for SMG cells that directly contributes to gland regeneration by supporting proliferation and differentiation of transplanted cells. As in vitro culture of salivary gland cells under adherent conditions leads to loss of secretory cell characteristics and reduced proliferation,101–103 we have adopted the use of microspheres, which have been shown to contribute to gland function after transplantation.10,13 It is generally acknowledged that the maintenance and expansion of functional salivary gland cells requires a biomaterial scaffold.21,24,104,105 Here, we have examined the feasibility of using PEG hydrogels. We have established permissive encapsulation procedures for multicellular SMG microspheres using thiol-ene polymerization.

In contrast to threedimensional (3D) studies performed with fibrin22 and hyaluronic acid,20,23,25 PEG is a bio-inert material26 that can be modified to provide specific biological cues in a novel “bottom up” approach to tissue engineering. Numerous ECM proteins that are important to salivary gland development and differentiation have been identified,106 and some of these such as laminin-11121 and perlecan23 have been incorporated into biomaterials. The inclusion of such matrix cues in PEG hydrogels will enable investigation of the specific effects of these modifications on encapsulated microsphere proliferation, cell composition and differentiation, and secretion of salivary factors. Previous studies used either immortalized cell lines or cells expanded from host tissues in vitro. These two sources of cells have translational limitations, as cell lines are unlikely to achieve regulatory approval for therapeutic applications, and mature salivary acinar cells have reduced proliferative capacity in vitro.102 Primary cells cultured in vitro also rapidly lose both polarity and secretory functions.101

As previously mentioned, microsphere preparation maintains the proliferative and differentiation capacity of salivary gland progenitor cells in vitro and has shown the ability to induce regeneration with in vivo models of radiation-induced salivary gland damage.8,10 One of the challenges of using cultured SMG microspheres is that the increasing microsphere size causes sedimentation and adherence to nontreated tissue culture plastic. PEG hydrogels were used to culture SMG cells till 14 days, providing a practical scaffold for the expansion and study of the fundamental characteristics of SMG microspheres over longer times than in typical suspension cultures.

In addition to providing bottom-up approaches to in vitro 3D cultures, PEG hydrogels can be photopolymerized in situ to transplant SMG cells to the gland. Previous work using a PEG hydrogel periosteum mimetic to deliver MSCs significantly improved bone healing in a segmental defect model.31,42 Critical to this approach was the localization and temporal release of MSCs provided by the PEG hydrogel,43 as MSCs seeded directly on an allograft have little effect on healing.107–109 In previous studies, transplantation of primary SMG cells into irradiated glands was performed using intraglandular ∼5–10 μL injections.10,12,13 We speculate that in situ polymerization of a hydrogel to surround damaged salivary glands may provide a direct means of delivering SMG cells for regeneration.

Conclusions

Methacrylate-based polymerizations that are commonly employed to form PEG hydrogels increase intracellular ROS and plasma membrane oxidation of SMG cells, resulting in significant losses in cell viability. Thiol-ene polymerizations represent a more favorable means for reproducible, cytocompatible hydrogel encapsulation of SMG cells. Similarly, the formation of multicellular microspheres is essential for the long-term viability of encapsulated SMG cells, which proliferate and comprise both acinar and duct cell lineages. Future studies will be focused on the use of thiol-ene hydrogels to transplant and direct SMG cell functions to regenerate salivary gland tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by NIH R01 DE022949, F30CA183320, and the University of Rochester Medical Scientist Training Program grant (T32 GM7356). The authors would also like to thank the Center for Musculoskeletal Research and Dr. James McGrath for use of their facilities, Dr. Linda Callahan and the URMC Imaging Core Facility for their help with confocal imaging, Dr. George Porter and Dr. Gisela Beutner for providing mice for submandibular gland dissection, Dr. Longze Zhang for his design of VisioPharm protocols to quantitate cell viability (VisioPharm funding provided by S10 RR027340, P30 AR061307, and P50 AR054041), Eri Maruyama for advice regarding immunostaining, Eric Comeau, Dr. Denise Hocking, and Dr. Diane Dalecki for sharing protocols for collagen gel fabrication, and Amy Van Hove for synthesizing norbornene-functionalized PEG used in these studies. The authors also thank Dr. Steve Konieczny (Purdue University) for donating Mist1-Cre mice and Michael Rogers for genotyping of Mist1-Cre and Krt5-Cre mice.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Jensen S.B., Pedersen A.M., Vissink A., Andersen E., Brown C.G., Davies A.N., Dutilh J., Fulton J.S., Jankovic L., Lopes N.N., Mello A.L., Muniz L.V., Murdoch-Kinch C.A., Nair R.G., Napenas J.J., Nogueira-Rodrigues A., Saunders D., Stirling B., von Bultzingslowen I., Weikel D.S., Elting L.S., Spijkervet F.K., Brennan M.T., Salivary Gland Hypofunction/Xerostomia Section; Oral Care Study Group; Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: management strategies and economic impact. Support Care Cancer 18, 1061, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassolato S.F., and Turnbull R.S. Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology 20, 64, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross M.H., and Pawlina W. Histology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006. New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamarin A. Submaxillary gland recovery from obstruction. I. Overall changes and electron microscopic alterations of granular duct cells. J Ultrastruct Res 34, 276, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker N.I., and Gobe G.C. Cell death and cell proliferation during atrophy of the rat parotid gland induced by duct obstruction. J Pathol 153, 333, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi S., Shinzato K., Nakamura S., Domon T., Yamamoto T., and Wakita M. Cell death and cell proliferation in the regeneration of atrophied rat submandibular glands after duct ligation. J Oral Pathol Med 33, 23, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arany S., Catalan M.A., Roztocil E., and Ovitt C.E. Ascl3 knockout and cell ablation models reveal complexity of salivary gland maintenance and regeneration. Dev Biol 353, 186, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rugel-Stahl A., Elliott M.E., and Ovitt C.E. Ascl3 marks adult progenitor cells of the mouse salivary gland. Stem Cell Res 8, 379, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okumura K., Nakamura K., Hisatomi Y., Nagano K., Tanaka Y., Terada K., Sugiyama T., Umeyama K., Matsumoto K., Yamamoto T., and Endo F. Salivary gland progenitor cells induced by duct ligation differentiate into hepatic and pancreatic lineages. Hepatology 38, 104, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombaert I.M., Brunsting J.F., Wierenga P.K., Faber H., Stokman M.A., Kok T., Visser W.H., Kampinga H.H., de Haan G., and Coppes R.P. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS One 3, e2063, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hisatomi Y., Okumura K., Nakamura K., Matsumoto S., Satoh A., Nagano K., Yamamoto T., and Endo F. Flow cytometric isolation of endodermal progenitors from mouse salivary gland differentiate into hepatic and pancreatic lineages. Hepatology 39, 667, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombaert I.M., Abrams S.R., Li L., Eswarakumar V.P., Sethi A.J., Witt R.L., and Hoffman M.P. Combined KIT and FGFR2b signaling regulates epithelial progenitor expansion during organogenesis. Stem Cell Reports 1, 604, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanduri L.S., Lombaert I.M., van der Zwaag M., Faber H., Brunsting J.F., van Os R.P., and Coppes R.P. Salisphere derived c-Kit+ cell transplantation restores tissue homeostasis in irradiated salivary gland. Radiother Oncol 108, 458, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim J.Y., Yi T., Choi J.S., Jang Y.H., Lee S., Kim H.J., Song S.U., and Kim Y.M. Intraglandular transplantation of bone marrow-derived clonal mesenchymal stem cells for amelioration of post-irradiation salivary gland damage. Oral Oncol 49, 136, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aframian D.J., Cukierman E., Nikolovski J., Mooney D.J., Yamada K.M., and Baum B.J. The growth and morphological behavior of salivary epithelial cells on matrix protein-coated biodegradable substrata. Tissue Eng 6, 209, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aframian D.J., Redman R.S., Yamano S., Nikolovski J., Cukierman E., Yamada K.M., Kriete M.F., Swaim W.D., Mooney D.J., and Baum B.J. Tissue compatibility of two biodegradable tubular scaffolds implanted adjacent to skin or buccal mucosa in mice. Tissue Eng 8, 649, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joraku A., Sullivan C.A., Yoo J.J., and Atala A. Tissue engineering of functional salivary gland tissue. Laryngoscope 115, 244, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joraku A., Sullivan C.A., Yoo J., and Atala A. In-vitro reconstitution of three-dimensional human salivary gland tissue structures. Differentiation 75, 318, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jean-Gilles R., Soscia D., Sequeira S., Melfi M., Gadre A., Castracane J., and Larsen M. Novel modeling approach to generate a polymeric nanofiber scaffold for salivary gland cells. J Nanotechnol Eng Med 1, 31008, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradhan S., Liu C., Zhang C., Jia X., Farach-Carson M.C., and Witt R.L. Lumen formation in three-dimensional cultures of salivary acinar cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142, 191, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantara S.I., Soscia D.A., Sequeira S.J., Jean-Gilles R.P., Castracane J., and Larsen M. Selective functionalization of nanofiber scaffolds to regulate salivary gland epithelial cell proliferation and polarity. Biomaterials 33, 8372, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCall A.D., Nelson J.W., Leigh N.J., Duffey M.E., Lei P., Andreadis S.T., and Baker O.J. Growth factors polymerized within fibrin hydrogel promote amylase production in parotid cells. Tissue Eng Part A 19, 2215, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradhan-Bhatt S., Harrington D.A., Duncan R.L., Jia X., Witt R.L., and Farach-Carson M.C. Implantable three-dimensional salivary spheroid assemblies demonstrate fluid and protein secretory responses to neurotransmitters. Tissue Eng Part A 19, 1610, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soscia D.A., Sequeira S.J., Schramm R.A., Jayarathanam K., Cantara S.I., Larsen M., and Castracane J. Salivary gland cell differentiation and organization on micropatterned PLGA nanofiber craters. Biomaterials 34, 6773, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradhan-Bhatt S., Harrington D.A., Duncan R.L., Farach-Carson M.C., Jia X., and Witt R.L. A novel in vivo model for evaluating functional restoration of a tissue-engineered salivary gland. Laryngoscope 124, 456, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratner B.D. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine, 2nd edn. Amsterdam, The Netherland: Elsevier Academic Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anseth K.S., Metters A.T., Bryant S.J., Martens P.J., Elisseeff J.H., and Bowman C.N. In situ forming degradable networks and their application in tissue engineering and drug delivery. J Control Release 78, 199, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawhney A.S., Pathak C.P., and Hubbell J.A. Bioerodible hydrogels based on photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(alpha-hydroxy acid) diacrylate macromers. Macromolecules 26, 581, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairbanks B.D., Schwartz M.P., Halevi A.E., Nuttelman C.R., Bowman C.N., and Anseth K.S. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv Mater 21, 5005, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elisseeff J., Anseth K., Sims D., McIntosh W., Randolph M., Yaremchuk M., and Langer R. Transdermal photopolymerization of poly(ethylene oxide)-based injectable hydrogels for tissue-engineered cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg 104, 1014, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman M.D., Xie C., Zhang X., and Benoit D.S. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells delivered via hydrogel-based tissue engineered periosteum on bone allograft healing. Biomaterials 34, 8887, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuttelman C.R., Tripodi M.C., and Anseth K.S. In vitro osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells photoencapsulated in PEG hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res Part A 68, 773, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benoit D.S., Schwartz M.P., Durney A.R., and Anseth K.S. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater 7, 816, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant S.J., and Anseth K.S. Hydrogel properties influence ECM production by chondrocytes photoencapsulated in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res 59, 63, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts J.J., and Bryant S.J. Comparison of photopolymerizable thiol-ene PEG and acrylate-based PEG hydrogels for cartilage development. Biomaterials 34, 9969, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farnsworth N., Bensard C., and Bryant S.J. The role of the PCM in reducing oxidative stress induced by radical initiated photoencapsulation of chondrocytes in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20, 1326, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdick J.A., and Anseth K.S. Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 23, 4315, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber L.M., He J., Bradley B., Haskins K., and Anseth K.S. PEG-based hydrogels as an in vitro encapsulation platform for testing controlled beta-cell microenvironments. Acta Biomater 2, 1, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin C.C., Raza A., and Shih H. PEG hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photo-click chemistry and their effect on the formation and recovery of insulin-secreting cell spheroids. Biomaterials 32, 9685, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahoney M.J., and Anseth K.S. Three-dimensional growth and function of neural tissue in degradable polyethylene glycol hydrogels. Biomaterials 27, 2265, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKinnon D.D., Kloxin A.M., and Anseth K.S. Synthetic hydrogel platform for three-dimensional culture of embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons. Biomater Sci 1, 460, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman M.D., and Benoit D.S. Emerging ideas: engineering the periosteum: revitalizing allografts by mimicking autograft healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471, 721, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman M.D., Van Hove A.H., and Benoit D.S. Degradable hydrogels for spatiotemporal control of mesenchymal stem cells localized at decellularized bone allografts. Acta Biomater 10, 3431, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Mofty S.K., and Kahn A.J. Early membrane injury in lethally irradiated salivary gland cells. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med 39, 55, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brizel D.M., Wasserman T.H., Henke M., Strnad V., Rudat V., Monnier A., Eschwege F., Zhang J., Russell L., Oster W., and Sauer R. Phase III randomized trial of amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 18, 3339, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konings A.W., Coppes R.P., and Vissink A. On the mechanism of salivary gland radiosensitivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 62, 1187, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grundmann O., Mitchell G.C., and Limesand K.H. Sensitivity of salivary glands to radiation: from animal models to therapies. J Dent Res 88, 894, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atsumi T., Murata J., Kamiyanagi I., Fujisawa S., and Ueha T. Cytotoxicity of photosensitizers camphorquinone and 9-fluorenone with visible light irradiation on a human submandibular-duct cell line in vitro. Arch Oral Biol 43, 73, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber L.M., and Anseth K.S. Hydrogel encapsulation environments functionalized with extracellular matrix interactions increase islet insulin secretion. Matrix Biol 27, 667, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin C.C., and Anseth K.S. Cell–cell communication mimicry with poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for enhancing beta-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 6380, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker J.L., Menko A.S., Khalil S., Rebustini I., Hoffman M.P., Kreidberg J.A., and Kukuruzinska M.A. Diverse roles of E-cadherin in the morphogenesis of the submandibular gland: insights into the formation of acinar and ductal structures. Dev Dyn 237, 3128, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu J.C., Koo H., Harunaga J.S., Matsumoto K., Doyle A.D., and Yamada K.M. Region-specific epithelial cell dynamics during branching morphogenesis. Dev Dyn 242, 1066, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menko A.S., Zhang L., Schiano F., Kreidberg J.A., and Kukuruzinska M.A. Regulation of cadherin junctions during mouse submandibular gland development. Dev Dyn 224, 321, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel V.N., and Hoffman M.P. Salivary gland development: a template for regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol 25–26, 52, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis M.A., and Reynolds A.B. Blocked acinar development, E-cadherin reduction, and intraepithelial neoplasia upon ablation of p120-catenin in the mouse salivary gland. Dev Cell 10, 21, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei C., Larsen M., Hoffman M.P., and Yamada K.M. Self-organization and branching morphogenesis of primary salivary epithelial cells. Tissue Eng 13, 721, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okumura K., Shinohara M., and Endo F. Capability of tissue stem cells to organize into salivary rudiments. Stem Cells Int 2012, 502136, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fairbanks B.D., Schwartz M.P., Bowman C.N., and Anseth K.S. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials 30, 6702, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin-Gibson S., Bencherif S., Cooper J.A., Wetzel S.J., Antonucci J.M., Vogel B.M., Horkay F., and Washburn N.R. Synthesis and characterization of PEG dimethacrylates and their hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 5, 1280, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Hove A.H., Wilson B.D., and Benoit D.S.W. Microwave-assisted functionalization of poly(ethylene glycol) and on-resin peptides for use in chain polymerizations and hydrogel formation. J Vis Exp (80), e50890, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Hove A.H., Beltejar M.J., and Benoit D.S. Development and in vitro assessment of enzymatically-responsive poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for the delivery of therapeutic peptides. Biomaterials 35, 9719, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anthis N.J., and Clore G.M. Sequence-specific determination of protein and peptide concentrations by absorbance at 205 nm. Protein Sci 22, 851, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress in cell culture: an under-appreciated problem? FEBS Lett 540, 3, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turrens J.F., Freeman B.A., Levitt J.G., and Crapo J.D. The effect of hyperoxia on superoxide production by lung submitochondrial particles. Arch Biochem Biophys 217, 401, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]