Abstract

In the common fruit fly Drosophila, head formation is driven by a single gene, bicoid, which generates head-to-tail polarity of the main embryonic axis. Bicoid deficiency results in embryos with tail-to-tail polarity and no head. However, most insects lack bicoid, and the molecular mechanism for establishing head-to-tail polarity is poorly understood. We have identified a gene that establishes head-to-tail polarity of the mosquito-like midge, Chironomus riparius. This gene, named panish, encodes a cysteine-clamp DNA binding domain and operates through a different mechanism than bicoid. This finding, combined with the observation that the phylogenetic distributions of panish and bicoid are limited to specific families of flies, reveals frequent evolutionary changes of body axis determinants and a remarkable opportunity to study gene regulatory network evolution.

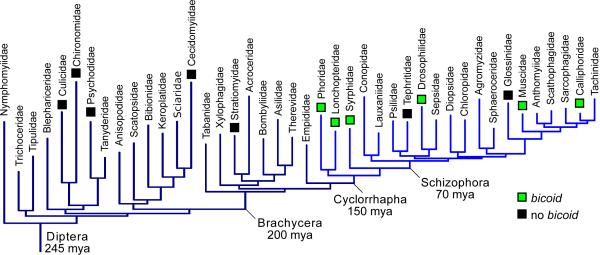

The bicoid gene of Drosophila melanogaster is involved in a variety of early developmental and biochemical processes. Many studies have examined its activity as a morphogen. Bicoid mRNA is maternally deposited into the egg and transported to the anterior side, forming a protein gradient that activates transcription of genes in a concentration-dependent manner (1–3). The bicoid gene represents an intriguing case of molecular innovation. It is related to Hox-3 genes of other animals but appears to be absent in most insects, including mosquitoes and other “lower” flies (Diptera) (4–6, Fig. 1). Bicoid-deficient embryos cannot develop a head or thorax and instead develop a second set of posterior structures that become a second abdomen (“double-abdomen”) when activity of another gene, hunchback, is disrupted simultaneously (7). Likewise, ectopically expressing bicoid in the posterior embryo prevents abdomen development and induces a “double-head” (8). Although other genes have been found to play a role in anterior development in beetles (9, 10) and wasps (11, 12), a gene responsible for anterior-posterior (AP) polarity has not been found. Nearly 30 years after the identification of bicoid in Drosophila, we have identified a gene that is necessary for the symmetry breaking and long-range patterning roles of bicoid in the harlequin fly Chironomus riparius. Further, we reexamined bicoid in several fly families and conclude that bicoid has been lost from genomes of some higher flies, including two lineages of agricultural and public health concern, the Tephritid and Glossinid flies (Figs. 1, S1, S2, and Table S1). These observations raise the possibility that bicoid has been frequently lost or substantially altered during radiations of dipterans.

Figure 1. Bicoid in dipteran families.

Indicated instances of missing bicoid orthologs (black) are based on genome sequences and tree is based on molecular phylogeny (see (22) and species list (23)).

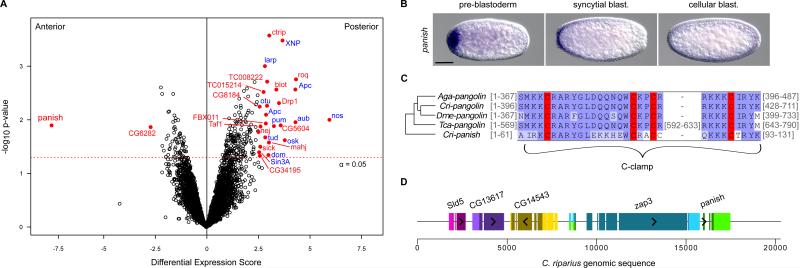

UV-light irradiation of anterior chironomid fly embryos induced double-abdomen formation, providing evidence of anterior localized RNA (13, 14). Therefore, we conducted gene expression profiling of AP bisected early C. riparius embryos to search for asymmetrically distributed maternal mRNA transcripts. All of the 6,604 identified transcripts were ranked according to the magnitude of the differential expression scores and p-values (Fig. 2A). Those most enriched in the posterior embryo were primarily homologs of known germ cell/plasm components (Fig. 2A, right side). This was anticipated because the germ plasm of Chironomus is located at the posterior pole. One transcript was highly biased in the anterior end of the early embryo (Fig. 2A, left side). We confirmed localized expression in early embryos for the two most biased transcripts (Figs. 2B, S3).

Figure 2. Panish mRNA is enriched in the anterior embryo and encodes a C-clamp protein.

A) Differential expression of transcripts based on RNA-sequencing data from anterior and posterior embryo halves. Red, score > 2.5 and p < 0.05. Blue, putative germ cell/plasm components. B) RNA in situ hybridizations of early embryos for panish. Anterior is left; scale bars, 10 μm. C) C-clamp region of panish aligned with Pangolin sequences from C. riparius (Cri), D. melanogaster (Dme), Anopheles gambiae (Aga), and Tribolium castaneum (Tca). Gray numbers, residues not shown; red, conserved cysteine residues; blue, residue similarity. D) The panish locus. Homology based on reciprocal-best-BLAST with D. melanogaster. Longest ORFs (shaded) and orientation (arrow heads) are indicated.

The anteriorly biased transcript contains an ORF encoding 131 amino acids. This predicted protein possesses a cysteine-clamp domain (C-clamp, residues 63-92) with similarity to the C-clamp of the Wnt signaling effector Pangolin/Tcf (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4) (15) and was therefore given the name panish (for “pan-ish”). However, neither the high mobility group (HMG) domain nor the β-catenin interaction domain of Pangolin is conserved in the protein sequence encoded by panish. Notably, we also identified a distinct pangolin ortholog expressed later in development during blastoderm cellularization at the anterior pole (Fig. S5). Duplication of a portion of the ancestral pangolin locus is a possibility given the strong similarity of their C-clamp domains. The panish C-clamp region appears to encode a bipartite nuclear localization signal (16) - hence, panish may be involved in transcriptional regulation. The 5’ end of the panish transcript (27/131 predicted residues) overlapped with an unrelated Chironomus transcript with homology to Drosophila ZAP3, a conserved nucleoside kinase gene. We mapped all transcripts onto genomic Chironomus sequence containing panish and determined that Chironomus ZAP3 (Cri-zap3) overlaps mostly with the large second panish intron (Fig. 2D) but was not differentially expressed between the anterior and posterior halves (p = 0.34).

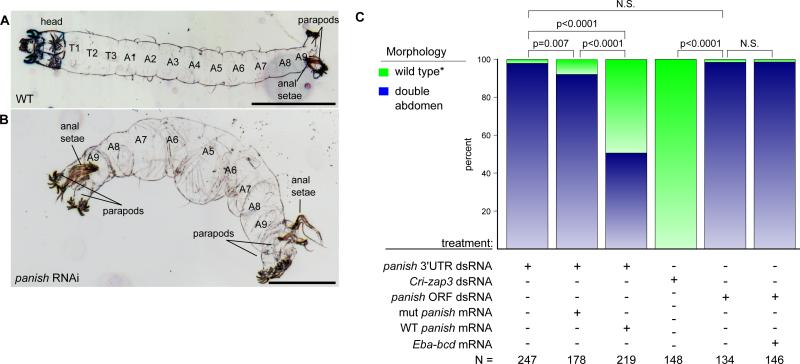

The panish transcript was tightly anteriorly localized in freshly laid eggs but was expressed more broadly in an anterior-to-posterior gradient by the beginning of the blastoderm stage (Fig. 2B). The panish transcript was not evident after blastoderm cellularization. To test whether the panish transcript was necessary for the AP axis, we conducted a series of loss- and gain-of-function experiments using double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and capped-mRNA injections. Early Chironomus embryos injected with dsRNA against the panish ORF or 3’UTR developed as double-abdomens (Figs. 3A-C and S6A) with similar survival rates between panish RNAi and controls. Notably, Cri-zap3 RNAi did not cause any obvious cuticle defects (Fig. 3C). Injection of panish dsRNA at the later blastoderm cellularization stage also had no effect, indicating that panish mRNA is dispensable at later stages (N = 112/112 WT).

Figure 3. Panish is required to establish AP polarity in C. riparius.

A) Inverted dark field image of wild-type first instar larval cuticle. A, abdominal; T, thoracic segment. B) Panish RNAi cuticle of symmetrical double-abdomen larva. Scale bars, 30 μm. C) Comparison of panish and Cri-zap3 RNAi phenotypes and rescue of the panish RNAi phenotype by anterior injection of panish mRNA. *Note: in the third column, “wild-type” includes 13 partial rescues (deformed head structures; Figs. S6B-D). N.S., p > 0.05; Eba-bcd from (6).

To confirm the requirement for panish mRNA in establishing the anterior domain, we performed rescue experiments by co-injecting either wild-type or out-of-frame mutated panish coding mRNA in combination with panish 3’UTR dsRNA. Double-abdomen formation was suppressed in over 40 percent of the embryos with the injection of wild-type panish mRNA into the anterior third of the embryo compared to injection of mutated panish mRNA, injection buffer, bicoid mRNA (Figs. 3C and S6B-D) and panish mRNA injection into the posterior third of the embryos (130/131 WT, p < 0.0001).

We also injected panish mRNA into the posterior wild-type embryo but did not observe double-head formation (214/214 WT). This observation suggests that Panish activity is constrained to the anterior embryo, potentially due to missing anterior components or the presence of anterior program inhibitors in the posterior embryo. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the expression and function of genes associated with embryonic axis specification in other insects (17). Candidate genes included orthologs of the anterior inhibitor nanos (Cri-nos), the anterior pattern organizers hunchback (Cri-hb) and orthodenticle/ocelliless (Cri-oc), and the posterior pattern organizers caudal (Cri-cad) and tailless (Cri-tll).

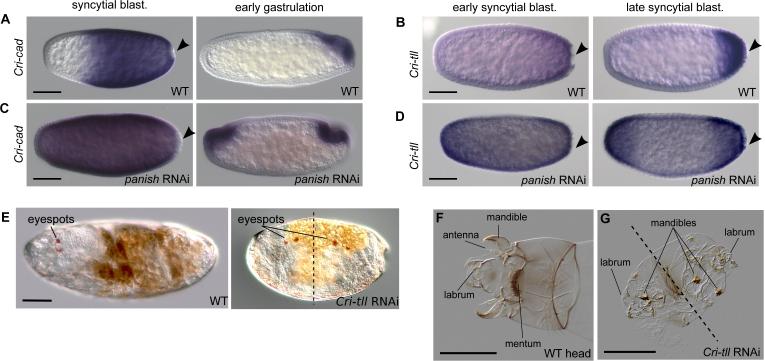

Maternal Cri-nos transcript was enriched at the posterior pole (Fig. S3) but neither Crinos RNAi nor ectopic Cri-nos expression affected axial patterning. Cri-hb and Cri-oc were present in the anterior blastoderm but RNAi against these genes only caused homeotic and gap phenotypes, respectively (Figs. S7A-D). Cri-cad was expressed in the posterior embryo and Cricad RNAi resulted in abdomen truncation (Figs. 4A and S7E). Therefore, these genes do not appear critical for embryonic AP polarity. Unlike Drosophila tailless, Cri-tll was expressed in a posterior-to-anterior gradient in early blastoderm stages (Fig. 4B). Following panish RNAi, both Cri-cad and Cri-tll were no longer expressed on one side, but instead were expressed symmetrically, consistent with their critical roles in abdomen development (Figs. 4C, D). Drosophila tailless encodes a nuclear receptor required for terminal structures of the abdomen and brain development but not the AP axis (18). In contrast, Cri-tll RNAi embryos not only lacked tail segments but about 70% developed malformed, often symmetrical, double-heads with duplicated mandible and labrum structures and eye spots (N=45, Figs. 4E-G, Fig. S8). This result was confirmed in independent RNAi experiments using non-overlapping dsRNAs (24/87 and 27/88 double heads).

Figure 4. Cri-cad and Cri-tll are regulated by panish and Cri-tll is required to establish AP polarity.

Staining for Cri-cad (A, C) and Cri-tll (B, D) with RNA in situ hybridization in wild-type and panish RNAi embryos. Black arrowheads, posterior pole cells. E) Eyespots indicated on live wild-type and Cri-tll RNAi embryos. Cuticle preparations of a WT larval head (F) and a Cri-tll RNAi larva (G). Dotted lines, approximate pane of symmetry. All panels, anterior is left; scale bars, 10 μm (except G- scale bar, 30 μm).

Duplication of head structures at both poles of the Cri-tll RNAi embryos suggests that unlike the Drosophila homolog, Cri-tll plays a role in AP polarity. Moreover, since Cri-tll is not expressed maternally, this further supports that maternal Cri-nos does not inhibit the formation of the anterior program. The observation that both heads of Cri-tll RNAi embryos develop with deformities is not surprising since Drosophila tll has a role in head development and Cri-tll may also play this part irrespective of its role in AP polarity.

A receptor tyrosine kinase gene, torso, controls the activation of tailless at the poles of the Drosophila blastoderm along with a second target, the zinc finger gene huckebein (19). We were unable to detect expression of the Chironomus homolog of huckebein (Cri-hkb) in early embryos (Fig. S9A). Cri-tor was expressed zygotically at the poles of the blastoderm embryo (Fig. S9B). Maternal Cri-tor transcript was detected in the RNA-seq data but not by RNA in situ hybridization. Cri-tor RNAi caused tail deletions and head defects similar to Cri-tll RNAi embryos but not double-heads (Fig. S9C). This finding suggests that Cri-tll has a role in axis polarity that is outside of its role in the terminal system driven by torso.

The double-head phenotype of Cri-tll RNAi embryos suggests a permissive role for panish in specifying embryonic AP polarity because the panish transcript was not detected in the posterior embryo. We suspected that Cri-tll might also have a permissive role in AP axis specification because Drosophila Tailless functions as a dedicated repressor (20). This was confirmed by double RNAi experiments against panish and Cri-tll that resulted in perfect double-abdomens (73/95 double-abdomen, 20/95 intermediate, 2/95 WT, Fig. S9D). However, it raises the question of why the default developmental program establishes a double-abdomen and not a double-head.

One possible explanation is that Panish functions as a direct activator of head genes. This would imply that there is Panish activity in the posterior, but it seems unlikely given the lack of detectable mRNA in the posterior of embryos in both the RNA-seq data and in situ hybridizations and the inability of panish mRNA to rescue the panish RNAi phenotype when panish mRNA is injected into the posterior third of the embryo. A more cogent possibility is that panish protein is more effective in repressing posterior genes than Cri-tll in repressing anterior genes. Knockdown of panish would therefore result in proportionally higher levels of posterior transcripts such as Cri-cad and consequently inhibit head formation. This interpretation is consistent with high penetrance of the double-abdomen phenotype following panish RNAi.

In conclusion, Drosophila bicoid and Chironomus panish encode structurally distinct DNA binding domain proteins that play similar essential roles in establishing AP polarity of the primary axis. In each case, the protein is necessary for breaking the symmetry of the primary axis and when inactive, results in duplication of the posterior domain. Bicoid is a transcriptional activator of anterior genes. However, Panish appears to be a repressor of posterior patterning genes (Fig. S10A). Moreover, maternally expressed nanos, which inhibits anterior programming in the posterior Drosophila embryo (21), appears to be ineffective in this regard in Chironomus. Two pieces of evidence argue against the existence of an additional, maternally localized, instructive factor for anterior development like bicoid in Chironomus. First, panish was the only transcript found strongly enriched at the anterior pole. Second, factors required for head development were also present in the posterior pole of Cri-tll embryos. We did not find evidence of panish in other dipteran genomes even though the locus is conserved in two closely related chironomid species, C. tentans and C. piger (Fig. S10B, Table S2). This suggests a recent origin of panish. Our study shows that mechanisms of AP patterning in insects are more labile than previously acknowledged. The functionally diverse primary axis determinants of fly embryos provide a remarkable opportunity for studying molecular innovations in the context of gene regulatory networks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank G. Bergtrom for Chironomus culture and equipment, T. Hankeln, F. Ripp, L. Wieslander, N. Visa for chironomid sequence data, J. E. Klomp for technical advice and discussions, M. Ludwig, S. Lott, M. Kim, C. Avila, A. Barnett, E. Davydova, T. Uchanski, C. Martinez, and Y. Yoon for technical help, J. Reinitz, M. Long, P. Rice, P. Faber, A. Ruthenberg, and C. Martinez for discussions, and C. Ferguson and M. Feder for laboratory equipment. This work was supported by the NIH (1R03HD67700-01A1), the NSF (IOS-1121211 and IOS-1355057), and the University of Chicago. T. S. was supported by Cell Networks Cluster of Excellence (EXC81).

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

Trascriptomic data are available at NCBI SRA (PRJNA229141).

Supplementary Materials: Materials and Methods Figures S1-S10 References (24-51) Tables S1-S2

References and Notes

- 1.Frohnhöfer HG, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Nature. 1986;324:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Cell. 1988;54:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Cell. 1988;54:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stauber M, Jackle H, Schmidt-Ott U. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A. 1999;96:3786–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stauber M, Prell A, Schmidt-Ott U. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A. 2002;99:274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012292899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemke S, et al. Development. 2010;137:1709–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driever W. In: The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Bate M, Arias AM, editors. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driever W, Siegel V, Nusslein-Volhard C. Development. 1990;109:811–820. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:7782–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116641109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotkamp K, Klingler M, Schoppmeier M. Development. 2010;137:1853–1862. doi: 10.1242/dev.047043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch JA, Brent AE, Leaf DS, Anne Pultz M, Desplan C. Nature. 2006;439:728–732. doi: 10.1038/nature04445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brent AE, Yucel G, Small S, Desplan C. Science. 2007;315:1841–1843. doi: 10.1126/science.1137528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalthoff K. Dev. Biol. 1971;25:119–132. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(71)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yajima H. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1964;12:89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atcha FA, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:8352–8363. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02132-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:10171–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg M, Lynch J, Desplan C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1789:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strecker TR, Merriam JR, Lengyel JA. Development. 1988;102:721–734. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brönner G, et al. Nature. 1994;369:664–668. doi: 10.1038/369664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morán É, Jiménez G. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:3446–3454. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3446-3454.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wharton RP, Struhl G. Cell. 1991;67:955–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegmann BM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A. 2011;108:5690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012675108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Materials and methods are available as supplementary material on Science Online.

- 24.Environment Canada, Biological Test Method: Test for survival and growth in sediment using larvae of freshwater midges (Chironomus tentans or Chironomus riparius) (Environmental Protection Service. 1997;EPS 1/RM/32 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemke S, Schmidt-Ott U. Development. 2009;136:117–27. doi: 10.1242/dev.030270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stauber M, Lemke S, Schmidt-Ott U. Dev. Genes Evol. 2008;218:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s00427-008-0204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amaya E, Musci TJ, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1991;66:257–270. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosman D, et al. Science. 2004;305:846–846. doi: 10.1126/science.1099247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tautz D, Pfeifle C. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern DL, Sucena E. In: Drosophila Protocols. Sullivan W, Ashburner M, Hawley RS, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 2000. pp. 601–615. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews Simon. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2011 http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/)

- 32.Martin M. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UC Davis Bioinformatics Core, sickle - A windowed adaptive trimming tool for FASTQ files using quality. Davis; CA, USA: https://github.com/ucdavis-bioinformatics/sickle. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Bruijn NG. Mathematics. Natuurkundig Laboratorium der N.V. Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken; Eindhoven, Netherlands: 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson JT, et al. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–1123. doi: 10.1101/gr.089532.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birol I, et al. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2872–2877. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durinck S, et al. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3439–3440. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camacho C, et al. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, et al. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gentleman RC, et al. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pages H, Aboyoun P, Gentleman R, DebRoy S. Biostrings: String objects representing biological sequences, and matching algorithms. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Hahne F. genefilter: methods for filtering genes from microarray experiments. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1540–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gille C, Frömmel C. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:377–378. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edgar RC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altschul SF, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, Brors B. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2811–2812. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Q, Bachtrog D. Science. 2012;337:341–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1225385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.