Abstract

Expression of the Wlds protein significantly delays axon degeneration in injuries and diseases, but the mechanism for this protection is unknown. Two recent reports present evidence that axonal mitochondria are required for WldS-mediated axon protection.

Axon degeneration is a pivotal pathological event in many acute and chronic neurological diseases. Remarkably, expression of the mutant Wallerian degeneration slow (WldS) protein strongly delays axonal degradation from various nerve injuries. Whereas wild-type axons begin to degenerate within hours of nerve transection, the distal segments of WldS axons remain structurally intact for weeks following the same injury, even long after the cell bodies have degenerated [1], indicating a degenerative process that is intrinsic to the axon and distinct from mechanisms governing cell body death [2,3]. The cellular targets of WldS activity that are responsible for conferring axonal protection, however, have remained a mystery. In this issue of Current Biology, two separate studies provide evidence that WldS enhances physiological functions of the mitochondria and show that axonal mitochondria are required for WldS-dependent axon protection [4,5].

WldS is a remarkable protein that significantly delays axonal degeneration from nerve injuries and diseases [6]. It is the product of a chimeric transcript consisting of the amino-terminal 70 amino acids of a ubiquitination factor (E4b) and the full functional sequence of a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) synthetic enzyme (NMNAT1) [7]. Expression of this fusion gene product in vitro and in vivo is sufficient to confer axon protection to wild-type axons. This protection is conserved across many species, including rodents and Drosophila [8,9]. Expression of the normally nuclear Nmnat1 enzyme in extranuclear compartments is sufficient to confer axon protection [10,11], and deletion of the Nmnat enzymatic domain in WldS abolishes axon protection [12,13], suggesting that extranuclear enzymatic activity of Nmnat is necessary and sufficient to promote axonal survival. But how WldS/Nmnat protein activities affect the normal axonal degeneration process has been a mystery.

To help identify additional molecular players critical for maintaining axonal survival, Fang et al. [5] screened 1,400 existing enhancer- and promoter-containing P-element (EP) lines in Drosophila to search for candidates that, when upregulated, can delay degeneration of axons after axotomy. To achieve this, the authors developed a novel axonal injury paradigm that allows for easy visualization and quantification of axonal degeneration. By using the Gal4–UAS system to express a GFP reporter under the control of the dprpGaw–Gal4 driver, which is expressed by a subset of sensory neurons along Drosophila wings, the authors could conveniently assay for axon degeneration by simply severing the wings and monitoring GFP fluorescence along the peripheral wing nerves.

One candidate that the authors identified from the screen was dNmnat, a Drosophila homologue of mammalian Nmnat. Upregulation of dNmnat strongly delayed axon degeneration after axotomy while knockdown of endogenous dNmnat by RNA interference (RNAi) led to spontaneous degeneration [5], showing that dNmnat is necessary and sufficient for axonal survival after injury. This is consistent with the previously reported role of Nmnat2, a mammalian Nmnat isoform, as an intrinsic axonal survival factor [14]. Moreover, the axonal degeneration resulting from loss of Drosophila dNmnat could be rescued by expression of Wlds and all mammalian Nmnat isoforms [5], suggesting that the activity of WldS as well as ectopic Nmnat is conserved and protects axons by substituting for the endogenous axonal trophic property of dNmnat.

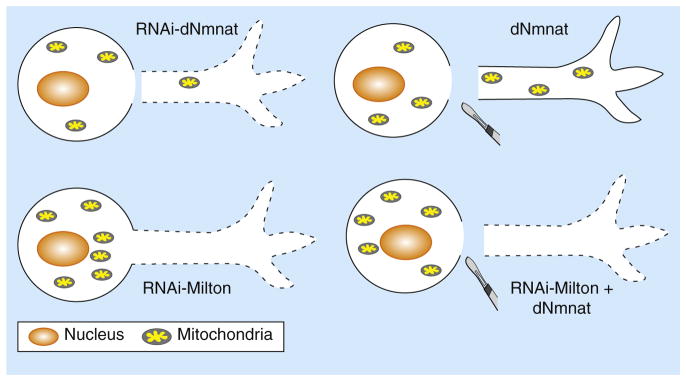

What might be the mechanism and cellular target of dNmnat- and WldS-mediated axonal protection? Insight into this issue came when Fang et al. [5] examined organelle dynamics in injured axons and observed that there was a concomitant decrease in the levels of mitochondria, as evidenced by decreased expression of mitochondria-targeted GFP, in the distal axon after axotomy as well as after knockdown of dNmnat [5]. Interestingly, this depletion of axonal mitochondria, which was not simply due to decreased availability of microtubule transport proteins, was fully rescued by upregulation of dNmnat, raising the possibility that dNmnat may function to stabilize the mitochondria and preserve their physiological functions in the axon (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A model of mitochondria-dependent axon protection.

The Drosophila protein dNmnat is necessary and sufficient for axonal survival, as RNAi-mediated knockdown of endogenous dNmnat induces spontaneous axon degeneration and depletion of mitochondria in the axon (top left), while upregulation of dNmnat delays axon degeneration from axotomy and rescues the depletion of axonal mitochondria (top right). Blocking mitochondrial entry into the axon by knocking down Milton, a linker protein required for anterograde mitochondrial transport, leads to spontaneous axon degeneration (bottom left). This degeneration cannot be rescued even with upregulation of dNmnat (bottom right), indicating that axonal mitochondria are required for dNmnat-mediated maintenance of normal axon survival and axon protection following nerve injuries.

What are the specific effects of WldS/Nmnat activity on mitochondria, and are these mitochondrial events responsible for conferring axonal protection by the WldS/Nmnat proteins? Findings from the second study by Avery et al. [4] provide a clue. Based on previous reports and the authors’ own observations that the majority of extranuclear WldS proteins are localized in the mitochondria [4,15], Avery et al. [4] hypothesized that WldS or Nmnat activity within the mitochondria may alter mitochondrial dynamics or functions to promote axonal survival. To test this, the authors performed laser axotomy on the peripheral axons of Drosophila larvae and found that, although mitochondrial movement was markedly diminished in the distal segments of wild-type axons after injury, mitochondrial motility was remarkably preserved in the injured WldS axons. In fact, despite having a similar number and size of mitochondria, uninjured WldS axons exhibited a significantly higher number of motile mitochondria than uninjured wild-type axons [4].

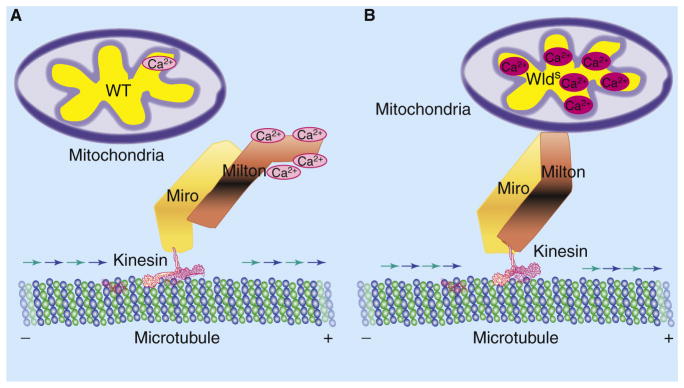

As Ca2+ induces undocking of mitochondria from the kinesin-dependent anterograde transport machinery [16], Avery et al. [4] further reasoned that the difference in mitochondrial motility between wild-type and WldS axons may reflect underlying differences in the levels of axonal Ca2+. Indeed, measuring intra-axonal Ca2+ levels after laser axotomy revealed a rapid Ca2+ spike in the injured wild-type axons, but this was significantly attenuated in WldS axons. Moreover, the suppression of the post-injury Ca2+ spike in WldS axons was dependent on enzymatic activity of Nmnat, as only the Nmnat isoforms that retain enzymatic activity showed attenuation of the injury-induced Ca2+ spike [4].

What can account for the differences in mitochondrial motility and Ca2+ levels between wild-type and WldS axons? As mitochondria are capable of buffering Ca2+ [17], it is possible that WldS or Nmnat activity may directly enhance mitochondrial buffering of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and thereby decrease Ca2+ levels in the axon. Moreover, as more Ca2+ is buffered by the mitochondria, less Ca2+ may be available in the axoplasm to undock mitochondria from microtubule-based transport, thereby increasing the overall number of motile mitochondria. In support of this idea, when the authors compared the Ca2+ loading capacity of purified wild-type and WldS mammalian mitochondria, they found that the WldS mitochondria exhibited greater intrinsic capacitance for Ca2+ than that of wild-type mitochondria, suggesting that WldS/Nmnat activity can directly enhance mitochondrial handling of Ca2+ [4] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. WldS activity in mitochondrial dynamics and function.

(A) In injured wild-type (WT) axons, an influx of extracellular Ca2+ exceeds the threshold of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering and leads to a local, transient increase of Ca2+ in the axon. Ca2+ binding to the Milton–Miro protein complex leads to undocking of mitochondria from the kinesin-dependent anterograde transport machinery, thereby decreasing mitochondrial movement. (B) In injured WldS axons, increased Ca2+ buffering by mitochondria decreases available free Ca2+ to bind to the Milton–Miro complex, thus maintaining the attachment of mitochondria to the anterograde transport machinery and preserving motility of mitochondria in the axon.

Importantly, do these mitochondrial dynamics contribute to axonal survival, and are the axonal mitochondria necessary targets for WldS/Nmnat-mediated axonal protection? To address these questions, both Fang et al. [5] and Avery et al. [4] used a clever method to suppress mitochondrial entry into the axon. Previously, it was found that mutations in Miro or Milton proteins, which are linker proteins required for kinesin-dependent anterograde transport of mitochondria, exclude mitochondria from the axon [18,19]. By taking advantage of this finding, the authors could effectively retain mitochondria in the soma and block entry of the organelle into the axon by decreasing protein levels or by perturbing normal functions of Miro or Milton.

Interestingly, when anterograde mitochondrial movement and entry into the axon are attenuated, both studies showed that the axonal protection by WldS or Nmnat upregulation was also greatly diminished. For instance, sequestration of mitochondria in the cell body by RNAi-mediated knockdown of Milton resulted in spontaneous, progressive degeneration of the axon, which could not be rescued by overexpression of WldS or dNmnat [5]. Similarly, expression of a mutant allele of Miro was sufficient to dominantly suppress WldS-mediated axonal protection [4]. Both studies therefore showed that expression of Nmnat or WldS proteins failed to protect axons after injury when Miro or Milton function was compromised, indicating that the presence of mitochondria in the axon is required for Nmnat/Wlds-mediated axonal protection (Figure 1). However, as it is unclear whether the transport of other organelles and proteins is also disrupted with decreased Miro/Milton function, it will be critical to differentiate whether the loss of WldS protection is due to decreased mitochondrial numbers and function in the axon, or simply to decreased transport or expression of the WldS protein in the axon.

The two reports together demonstrate that WldS/Nmnat activity enhances mitochondrial motility and Ca2+ buffering and that the mitochondrion is an organelle necessary for WldS/Nmnat-mediated axonal protection. The processes regulating axon degeneration and the WldS/Nmnat enzymatic activities that are critical for axonal protection thus converge at axonal mitochondria. A clear future direction is to address whether directly enhancing these mitochondrial functions is sufficient to exert axonal protection. Moreover, identifying whether known enzymatic metabolites of the WldS/Nmnat proteins, such as NAD+, interact with molecules in the mitochondria will be instrumental in understanding the full downstream mechanisms of WldS/Nmnat-mediated axon protection. Although there is still much to learn about the molecular processes regulating axonal degeneration and survival, these two reports have given us a boost by placing the focus squarely on the axonal mitochondria.

References

- 1.Deckwerth TL, Johnson EM., Jr Neurites can remain viable after destruction of the neuronal soma by programmed cell death (apoptosis) Dev Biol. 1994;165:63–72. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JT, Medress ZA, Barres BA. Axon degeneration: molecular mechanisms of a self-destruction pathway. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:7–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman MP, Freeman MR. Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avery MA, Rooney T, Wishart TM, Pandya JD, Gillingwater TH, Geddes JW, Sullivan P, Freeman MR. WldS prevents axon degeneration through increased mitochondrial flux and enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. Curr Biol. 2012;22:596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang Y, Soares L, Teng X, Geary M, Bonini N. A novel Drosophila model of nerve injury reveals an essential role of Nmnat in maintaining axonal integrity. Curr Biol. 2012;22:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunn ER, Perry VH, Brown MC, Rosen H, Gordon S. Absence of Wallerian degeneration does not hinder regeneration in peripheral nerve. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack TG, Reiner M, Beirowski B, Mi W, Emanuelli M, Wagner D, Thomson D, Gillingwater T, Court F, Conforti L, et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoopfer ED, McLaughlin T, Watts RJ, Schuldiner O, O’Leary DD, Luo L. Wlds protection distinguishes axon degeneration following injury from naturally occurring developmental pruning. Neuron. 2006;50:883–895. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald JM, Beach MG, Porpiglia E, Sheehan AE, Watts RJ, Freeman MR. The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron. 2006;50:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beirowski B, Babetto E, Gilley J, Mazzola F, Conforti L, Janeckova L, Magni G, Ribchester RR, Coleman MP. Non-nuclear Wld(S) determines its neuroprotective efficacy for axons and synapses in vivo. J Neurosci. 2009;29:653–668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3814-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki Y, Vohra BP, Baloh RH, Milbrandt J. Transgenic mice expressing the Nmnat1 protein manifest robust delay in axonal degeneration in vivo. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6526–6534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1429-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avery MA, Sheehan AE, Kerr KS, Wang J, Freeman MR. Wld S requires Nmnat1 enzymatic activity and N16-VCP interactions to suppress Wallerian degeneration. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:501–513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conforti L, Wilbrey A, Morreale G, Janeckova L, Beirowski B, Adalbert R, Mazzola F, Di Stefano M, Hartley R, Babetto E, et al. Wld S protein requires Nmnat activity and a short N-terminal sequence to protect axons in mice. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:491–500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilley J, Coleman MP. Endogenous Nmnat2 is an essential survival factor for maintenance of healthy axons. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yahata N, Yuasa S, Araki T. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase expression in mitochondrial matrix delays Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6276–6284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4304-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Schwarz TL. The mechanism of Ca2+-dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacAskill AF, Kittler JT. Control of mitochondrial transport and localization in neurons. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glater EE, Megeath LJ, Stowers RS, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria requires milton to recruit kinesin heavy chain and is light chain independent. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:545–557. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stowers RS, Megeath LJ, Gorska-Andrzejak J, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron. 2002;36:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]