Abstract

Background:

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) is a frequent, complex and cumbersome condition that can cause physical and psychological distress for the involved individual. Candida albicans was reported as the most common agent of VVC yet it seems that we are recently encountering changes in the pattern of Candida species in VVC.

Objectives:

In this study we assessed different species of Candida isolated from patients with VVC, residing in Sari, Iran.

Patients and Methods:

Two hundred and thirty-four patients with vulvovaginitis were enrolled in this study. Samples were collected by a wet swab. Each vaginal swab was examined microscopically and processed for fungal culture. The identification of Candida species was done by morphological and physiological methods such as culture on CHROMagar Candida media and sugar assimilation test with the HiCandida identification kit (HiMedia, Mumbai, India).

Results:

Out of 234 patients with vulvovaginitis, 66 (28.2%) patients showed VVC. Of these patients, 16 (24.2%) had recurrent VVC (RVVC). The age group of 20 - 29 year-olds had the highest frequency of VVC (48.5%). Erythema concomitant with itching (40.9%) was the most prevalent sign in VVC patients. Fifty-seven (86.4%) of the collected samples had positive results from both microscopic examination and culture. In total, 73 colonies of Candida spp. were isolated from 66 patients with VVC. The most common identified species of Candida were C. albicans (42.5%), C. glabrata (21.9%) and C. dubliniensis (16.4%). In patients with RVVC and patients without recurrence, C. albicans and non-albicans species of Candida were frequent species, respectively.

Conclusions:

The results of our study showed that non-albicans species of Candida are more frequent than C. albicans in patients with VVC. This result is in line with some recent studies indicating that non-albicans species of Candida must be considered in gynecology clinics due to the reported azole resistance in these species.

Keywords: Incidence, Candida, Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

1. Background

Vulvovaginitis is a cumbersome condition indicated by irritation of vulva, vagina, or both. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC), as an important subtype, is characterized by severe itching of vulva, abnormal vaginal discharge, erythema, edema of vulva, and satellite lesions (1). Many studies have shown that 75% of the female population will have at least one episode of VVC and 40 - 50% will have recurrent episodes, during their lifetime (2-4). Despite several treatment modalities and application of new effective drugs, VVC is a complex and considerable problem in gynecology and obstetrics (4). On the other hand, in the recent years different studies in different countries have illustrated that the involved species of this disease is also changing (1, 5-7).

In the study of Aalei et al. (8), Candida albicans and non-albicans species of Candida were responsible for 75% and 25% of VVC cases, respectively. According to the study of Jamilian et al. (6), C. albicans was isolated in 42.03% of VVC patients, while in the remaining cases, the disease was caused by other Candida species. This pattern of change was also noted in other countries (2, 5, 9). Ahmad et al. (9) reported a prevalence of 53.1% of non-albicans species among patients with VVC, where C. glabrata (36.7%) was the most common isolated species. The non-albicans species were shown to be important causative agents for recurrence and chronicity of the disease and many of them were resistant to common antifungal drugs (9). There are increasing reports on fluconazole (as a first line therapy for VVC) resistance in some Candida species (5, 6, 10, 11). This disease, not only affects physical and psychological health of patients, but also imposes a significant financial expenditure and difficulties for marital relationships, and may even lead to infertility (12).

2. Objectives

In this study we assessed the incidence of different species of Candida in patients with VVC to gain new information on involved species and the prevalence of the disease in Sari, Iran.

3. Patients and Methods

This research was a descriptive analytical cross-sectional study. Patients were enrolled in the study by the sequential sampling method. The participants were married women aged 20 - 60 years, who presented erythema and itching of vulva, vagina, or both and cheesy vaginal discharge. The patients filled out a consent form to participate in the research, which was approved by the ethical committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Concomitant with each obtained specimen, a questionnaire was completed for each patient enquiring about their age, marital status, duration of symptoms, comorbidities, signs and symptoms of current condition, methods of pregnancy prevention, prior parturitions, and history of antibiotic consumption. Patients with four or more discrete attacks of VVC per year were considered as having Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (RVVC).

3.1. Sample Collection and Laboratory Diagnosis

Vaginal secretions were obtained in lithotomic position using a speculum and sterile swabs. Two specimens were collected simultaneously under sterile conditions, one for light microscopic examination and the other for fungal culture. For each of the samples, a slide was prepared for Gram staining. The sample for fungal culture was inoculated into Sabouraud’s glucose agar (Merck, Germany) supplemented with chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) (SDA) and incubated at 30°C. The identification of the Candida species was done by morphological and physiological methods such as culture on CHROMagar Candida media (CHROMagar Company, France), germ tube test, chlamydospore forming test on corn meal agar media (HiMedia, Mumbai, India), growth at 45°C and sugar assimilation test with the HiCandida identification kit (HiMedia, Mumbai, India).

HiCandida identification kit was applied for precise identification of Candida species as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The plastic strip had twelve wells with sterile medium for different biochemical tests as follow: well 1, medium for the urease detection test, and well 2 - 12, medium for carbohydrate utilization test (with eleven different sugars in respective wells, including, melibiose, lactose, maltose, sucrose, galactose, cellobiose, inositol, xylose, dulcitol, raffinose and trehalose). In brief, the test was performed as follows; at first a homogenous yeast suspension (1 to 5 × 106 cell/mL) was prepared and inoculated into kit wells and incubated for 24 - 28 hours at 22.5 ± 2.5°C. A standard sample of C. albicans (as confirmed by the molecular method) was also used as the control. After the incubation period the change of color in the kit was noted: well 1 containing urease was considered positive if the yellow color transformed to pink. Wells 2-12 were considered positive if their orange-red color changed to yellow; these pits were left for 72 hours and if the color was still orange, the result was considered negative. Interpretation of the results was based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.2. Statistical Analyses

Chi-square test was performed using the SPSS software (version 18.0) and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

4. Results

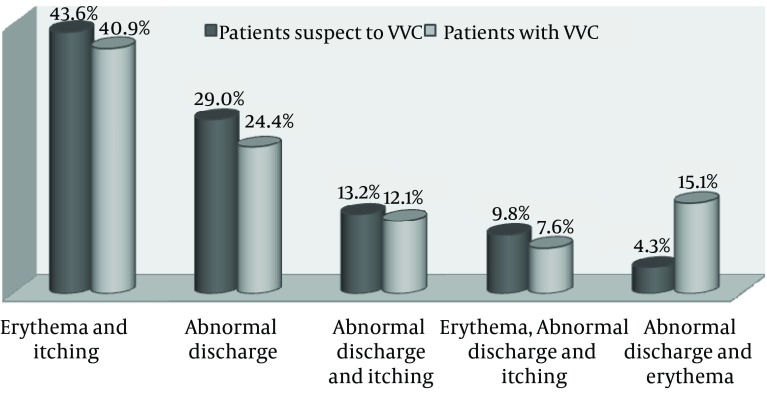

During one year, we studied 234 consecutive patients suspected of VVC at Boo Ali hospital of Sari city, Iran (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 34.17 ± 9 years. Out of 234 patients with vulvovaginitis, 66 (28.2%) patients showed VVC. Of these patients, 16 (24.2%) had RVVC. The mean age of VVC patients was 31.82 ± 10 years. The age group of 20 - 29 year-olds had the highest frequency of VVC (48.5%). No significant correlation was found between age and occurrence of VVC (P = 0.137). Figure 1 shows vulvovaginal symptoms and signs in patients suspected of VVC and VVC patients. Erythema concomitant with itching (40.9%) was the most prevalent sign in VVC patients and patients suspected of VVC. No significant correlation was observed between occurrence of the disease and type of symptoms (P = 0.608). Table 2 shows the distribution of studied patients based on the use of contraception methods. Most patients with VVC (45.4%) did not use any method of contraception. In total, 27.8% of patients suspected of VVC had positive results for the culture method.

Table 1. Distribution of Studied Patients Based on age Groupsa, b.

| Patients’ Age Group | Patients Suspected of VVC | Patients With VVC |

|---|---|---|

| 20 - 29 | 78 (33.3) | 32 (48.5) |

| 30 - 39 | 78 (33.3) | 18 (27.3) |

| 40 - 49 | 64 (27.5) | 12 (18.2) |

| 50 - 60 | 14 (6.0) | 4 (6.1) |

| Total | 234 (100.0) | 66 (100.0) |

aAbbreviation: VVC, Vulvovaginal candidiasis.

bData are presented as No. (%).

Figure 1. Vulvovaginal Symptoms and Signs in Patients Suspected of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Patients.

Table 2. Distribution of Studied Patients Based on the Use of Contraception Methodsa,b.

| Patients Contraception Method | Patients Suspected of VVC | Patients With VVC |

|---|---|---|

| No contraceptive method | 66 (28.2) | 30 (45.4) |

| Natural | 59 (25.2) | 17 (25.7) |

| Condoms | 50 (21.4) | 7 (10.6) |

| Oral contraception | 12 (5.1) | 6 (9.1) |

| IUD | 8 (3.4) | 4 (6.1) |

| Tubectomy | 39 (16.7) | 2 (3.0) |

| Total | 234 (100.0) | 66 (100.0) |

aAbbreviation: VVC, Vulvovaginal candidiasis.

bData are presented as No. (%).

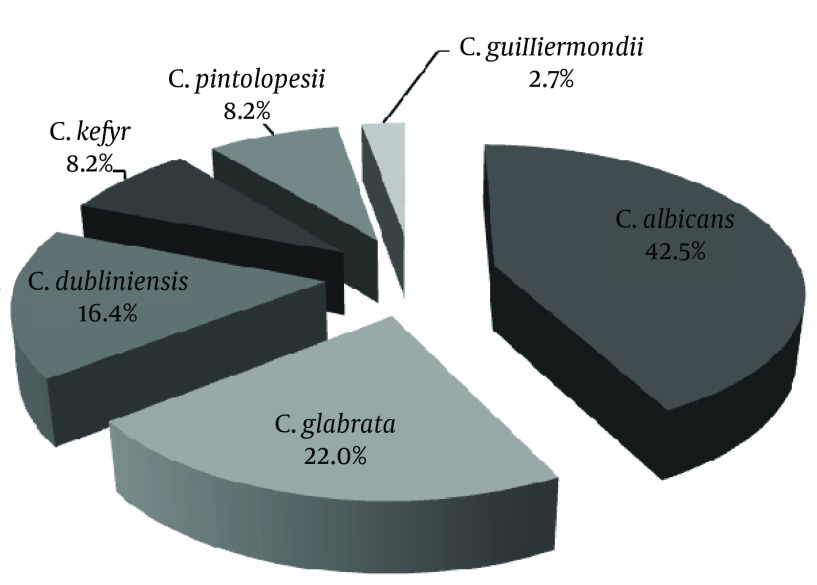

Out of 66 patients with VVC, 98.5% had positive results for Candida growth in culture. Of these patients, 56 (84.8%) had positive results for both microscopic examination and culture. Nine patients (13.6%) showed positive results in culture but not in microscopic examination. Out of 57 patients with positive results in microscopic examination, 30 cases (52.6%) showed yeast and budding yeast and 27 (47.4%) pseudohyphae and budding yeast. In total, 73 colonies of Candida spp. were isolated from 66 patients with VVC. The most frequent species of Candida were C. albicans (42.5%), C. glabrata (22.0%) and C. dubliniensis (16.4%) (Figure 2). Out of a total of 66 patients with VVC, 16 (24.2%) cases showed RVVC. In 16 patients with RVVC, Candida. albicans was responsible in nine (56.2%). On the other hand, non-albicans species of Candida (68.0%) were frequent species in patients without recurrence (Table 3). There was no significant correlation between Candida species and recurrent or non-recurrent pattern of disease (P = 0.073).

Figure 2. Distribution of Isolated Candida Species From Patients With Vulvovaginal Candidiasis.

Table 3. Distribution of Studied Patients Based on age Groups a.

| Patients Candida Species | RVVC Patients | VVC Patients |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 9 (56.2) | 16 (32.0) |

| C. dubliniensis | 1 (6.2) | 10 (20.0) |

| C. glabrata | 3 (18.2) | 7 (14.0) |

| C. kefyr | 0 | 6 (12.0) |

| C. pintolopesii | 0 | 6 (12.0) |

| C. guilliermondii | 0 | 1 (2.0) |

| C. albicans + C.guilliermondii | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| C. albicans + C. glabrata | 2 (12.5) | 3 (6.0) |

| C. dubliniensis + C. glabrata | 0 | 1 (2.0) |

aAbbreviation: RVVC, Recurrent Vulvovaginal candidiasis; VVC, Vulvovaginal Candidiasis.

5. Discussion

Candidiasis is one of the most diverse fungal infections that can lead to superficial, such as vaginitis, to systemic and potentially life-threatening diseases. Genital involvement in women is one of the most common presentations due to Candida. Vulvovaginal candidiasis results from abnormal growth of Candida in the genital tract mucosa and has increased dramatically in the recent years (13). This infection is a worldwide health problem and affects millions of women, annually (13). Candida albicans was reported as the most common agent of VVC yet it seems that we are recently encountering changes in the pattern of Candida species in VVC. This is why we designed a study to evaluate VVC and the incidence of different species of Candida in patients from Iran.

In the present study out of 234 patients with vulvovaginitis, 66 (28.2%) showed VVC. Of these patients, 24.2% had RVVC. The incidence of VVC and RVVC varied in different studies (6, 14, 15). In some reports from Iran the incidence of VVC was 5 - 10% (14), 33.3% (6) and 47.3% (15). A survey by Foxman et al. (16) in the US showed that 6.5% and 8% of women older than 18 years of age reported ≥ 1 and ≥ 4 episodes of VVC during the two months and one year prior to the survey, respectively. In two population-based studies from the USA, 55% (17) and 56% (18) of studied women experienced at least one episode of VVC during their lifetime and that 8% of women experienced RVVC. This variation may be due to inaccuracies in pathogen detection, mismanagement, drug resistance, incomplete therapeutic course, self-treatment, lack of appropriate health habits and intestinal infestation (19). However, Achkar and Fries (20) suggested that VVC is not a reportable disease and is often diagnosed without confirmatory tests and treated with over-the-counter (OTC) medications, and thus its exact incidence is unknown. In the present study the age group of 20 - 29 year-olds had the highest frequency of VVC, which is concordant with the findings of Mahmoudi Rad et al. (15) and Asadi et al. (21) from Iran and Adesiji et al. (22) from Nigeria.

In our study, similar to the study of Aalei et al. (8), no statistical significance was found between age and occurrence of the disease. This may be due to higher vaginal discharge, physiological and hormonal changes, higher sexual activity, vaginal flora changes, the childbearing age and use of various contraceptive facilities in this age group. In the present study, VVC was mostly observed in those who used natural methods for pregnancy prevention. There was a significant correlation between contraceptive method and disease acquisition (P = 0.004). These results are in agreement with the study of Torabi and Amini (23) from Zanjan, however, in contrary with some previous studies (3, 7, 8). It may be assumed that this non-protective method increases the chances of VVC. In our study, the most common symptom was erythema concomitant with itching in VVC patients and there was a statistically significant correlation between this symptom and VVC. However, typical VVC signs, such as cheesy discharge, erythema and itching were not significantly related to VVC. The same result was reported by some other previous studies (24, 25). Michigan university researchers also reported itching as the most common symptom in VVC (26).

The mild invasion of epithelial cells in the lower genitalia tract by Candida causes widespread itching and inflammation due to a toxin or enzyme involved in pathogenesis by Candida (13). As the vulva is involved, the disease is often accompanied by vaginitis, itching, burning, and erythema of vagina and vulva, which are considered as the most common symptoms of VVC. In the present study, 27.8% of patients who were suspected of VVC had positive culture results. This percentage is higher than that reported by Aalei et al. (8) and Torabi and Amini (23), who reported a culture positivity of 19.8% and 4.8% in Kerman and Zanjan (two central province of Iran with different climates) respectively. However, some studies (5, 14, 27, 28) reported a higher positivity than that observed in our study, yet our results generally agreed with previous studies (21, 22, 29). This variation of results may be related to different climate and geographical conditions, cultural specifications, health habits, various experimental designs, sampling criteria, and various prevalence of non-fungal infection.

In our study, out of 66 patients with VVC, 98.5% of samples showed Candida growth in culture. Of these patients, 13.6% had positive culture results yet negative microscopic examination results. These results indicate the strength of the culture method in comparison with microscopic examination for VVC diagnosis. In this study, the prevalence of C. albicans and non-albicans species of Candida was 42.5% and 57.5%, respectively. According to previous Iranian and other studies from different countries, C. albicans was the most involved species of Candida in VVC patients (6, 8, 9, 14, 27, 30, 31). Grigoriou et al. (32) attributed this to the greater ability of C. albicans in adhesion to vaginal mucosa, which is the primary step in establishment of a fungal infection. In our study C. glabrata was the second leading species that caused infection, and this finding was consistent with many previous studies (11, 22, 27, 28, 33). Although in our study, C. albicans was the most prevalent isolated species of Candida yet in comparison to non-albicans species, the latter was predominant. During the last decade, different studies have shown an increase in isolation of non-albicans species in VVC patients (6, 28, 33). Sobel et al. (34) suggested that this pattern may be due to incomplete local or systemic therapeutic regimens, or self-prescribed anti-fungal agents and the increasing use of prolonged anti-fungal courses to prevent recurrence of VVC.

Some of the non-albicans species such as C. glabrata respond poorly to azole agents, especially fluconazole, which can be a reason for the increased prevalence of non-albicans species of Candida in VVC patients (20). In our study, C. pintolopesii was isolated from 12% of VVC patients without recurrences; a finding which was different from other previous studies. Savage and Dubos (35) have shown that C. pintolopesii is the normal flora yeast of rodents. In the present study CHROMagar Candida medium was applied to differentiate Candida species phenotypically. This method detects only two major Candida species. In the recent years, non-albicans species, which are concomitant with some yeast species and produce similar colors, have expanded leading to inaccurate diagnosis and treatment failure. In addition, colorimetric techniques are expensive for routine use.

We applied the HiCandida kit for final differentiation of Candida species. This kit identified six species of Candida. Bose et al. (36) used the same method to identify Candida species obtained from ICU patients and reported satisfactory results. The results of our study showed that non-albicans species of Candida were more frequent than C. albicans (57.5% vs. 42.5%) in patients with VVC. This result is in line with some recent studies that have indicated that non-albicans species of Candida must be considered in gynecology clinics because of the reported azole resistance in these species.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all patients who participated in this study for their kind co-operation, which was essential for the completion of the study.

Footnotes

Funding/Support:This study was supported by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari (Iran) (University Ethics Committee code: 89-172).

References

- 1.Quan M. Vaginitis: diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(6):117–27. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.11.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Souza PC, Storti-Filho A, Souza RJ, Damke E, Mello IC, Pereira MW, et al. Prevalence of Candida sp. in the cervical-vaginal cytology stained by Harris-Shorr. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(5):625–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0765-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou X, Westman R, Hickey R, Hansmann MA, Kennedy C, Osborn TW, et al. Vaginal microbiota of women with frequent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2009;77(9):4130–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00436-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidel PJ. History and update on host defense against vaginal candidiasis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;57(1):2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trama JP, Adelson ME, Raphaelli I, Stemmer SM, Mordechai E. Detection of Candida species in vaginal samples in a clinical laboratory setting. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2005;13(2):63–7. doi: 10.1080/10647440400025629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamilian M, Mashadi E, Sarmadi F, Banijamali M, Farhadi E, Ghanatpishe E. Frequency of vulvovaginal Candidiasis species in nonpregnant 15-50 years old women in spring 2005 in Arak. Arak Univ Med Sci J. 2005;10(2):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etminan S, Zarinkatsh H, Lotfee M. The Prevalence of Candida Vaginitis among Women aged 15-49 Years in Yazd, Iran. Med Lab J. 2008;2(1):39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aalei BSH, Touhidi A. Prevalence of Candida vaginitis among symptomatic patients in Kerman. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2000;13:42–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad A, Khan AU. Prevalence of Candida species and potential risk factors for vulvovaginal candidiasis in Aligarh, India. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(1):68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter SS, Galask RP, Messer SA, Hollis RJ, Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA. Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida species causing vulvovaginitis and epidemiology of recurrent cases. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(5):2155–62. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2155-2162.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonyadpour B, Akbarzdeh M, Pakshir K, Mohagheghzadeh A. In vitro susceptibility of fluconazole, clotrimazole and toucrium polium smoke product on Candida isolates of vaginal candidiasis. J Armaghan Danesh. 2010;2:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verghese S, Padmaja P, Asha M, Elizabeth SJ, Anitha A, Kundavi KM, et al. Prevalence, species distribution and antifungal sensitivity of vaginal yeasts in infertile women. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44(3):313–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilkit M, Guzel AB. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidosis: a mycological perspective. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37(3):250–61. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.576332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoudabadi Zarei A, Najafyan M, Alidadi M. Clinical study of Candida vaginitis in Ahvaz, Iran and susceptibility of agents to topical antifungal. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26(3):607–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahmoudi Rad M, Zafarghandi S, Abbasabadi B, Tavallaee M. The epidemiology of Candida species associated with vulvovaginal candidiasis in an Iranian patient population. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foxman B, Barlow R, D'Arcy H, Gillespie B, Sobel JD. Candida vaginitis: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(4):230–5. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiger AM, Foxman B, Gillespie BW. The epidemiology of vulvovaginal candidiasis among university students. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8 Pt 1):1146–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foxman B. The epidemiology of vulvovaginal candidiasis: risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(3):329–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(5):757–65. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achkar JM, Fries BC. Candida infections of the genitourinary tract. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):253–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asadi MA, Rasti S, Arbabi M, Hooshyar H, Yoosefdoost H. Prevalence of vaginal Candidiasis in married women referred to Kashan's health centers, 1993-94. J Kashan Univ Med Sci FEYZ. 1997;1(1):21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adesiji YO, Ndukwe N, Okanlawon BM. Isolation and antifungal sensitivity to Candida isolates in young females. Cent Eur J Med. 2011;6(2):172–6. doi: 10.2478/s11536-010-0071-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torabi M, Amini B. The relation of health behavior with vaginal infection in woman referred to family planning clinics of Zanjan. Zanjan J Med Sci. 1996;21:49–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shokohi T. [Survey of Candida vulvovaginitis in outpatients referred to gynecology-obstetrics clinics of Sari (1993-94)]. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 1996;19-18(5):22–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karmastaji A, Khajeh FGH, Amirian M. Comparison between clinical and laboratory diagnosis of vaginitis. Med J Hormozgan Univ. 2005;9(2):131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonhart YM, Tlymann WR. Vulvovaginitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;20(s):473–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel JD, Kapernick PS, Zervos M, Reed BD, Hooton T, Soper D, et al. Treatment of complicated Candida vaginitis: comparison of single and sequential doses of fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(2):363–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foladvand M, Naeimi B, Haghighi M. Identification of Candida species isolated of vaginitis in woman referred to specialized hospital Bushehr. J Bushehr Univ Med Sci. 2011;2:113–08. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holland J, Young ML, Lee O, C. A. Chen S Vulvovaginal carriage of yeasts other than Candida albicans. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(3):249–50. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy MA, Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Caused by Non-albicans Candida Species: New Insights. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):465–70. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gumral R, Sancak B, Guzel AB, Saracli MA, Ilkit M. Lack of Candida africana and Candida dubliniensis in vaginal Candida albicans isolates in Turkey using HWP1 gene polymorphisms. Mycopathologia. 2011;172(1):73–6. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grigoriou O, Baka S, Makrakis E, Hassiakos D, Kapparos G, Kouskouni E. Prevalence of clinical vaginal candidiasis in a university hospital and possible risk factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126(1):121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes Consolaro ME, Aline Albertoni T, Shizue Yoshida C, Mazucheli J, Peralta RM, Estivalet Svidzinski TI. Correlation of Candida species and symptoms among patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis in Maringa, Parana, Brazil. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2004;21(4):202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, Foxman B, Ledger WJ, Nyirjesy PR, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(2):203–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage DC, Dubos RJ. Localization of indigenous yeast in the murine stomach. J Bacteriol. 1967;94(6):1811–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.6.1811-1816.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bose S, Ghosh AK, Barapatre R. The incidence of Candiduria in an ICU. J Clin Diag Res. 2011;5(2):227–30. [Google Scholar]