Abstract

Ginsenosides, the main effective components of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer and Panax quinquefolius L., are important allelochemicals of ginseng. Although many studies have targeted the pharmacological, chemical, and clinical properties of ginsenosides, little is known about their ecological role in ginseng population adaptation and evolution. Pests rarely feed on ginseng, and it is not known why. This study investigated the effects of total ginsenosides on feeding behavior and activities of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and glutathione s-transferase (GST) in Mythimna separata (Walker) larvae. The results showed that the total ginsenosides had significant antifeeding activity against M. separata larvae, determined by nonselective and selective antifeeding bioassays. In addition, the total ginsenosides had inhibitory effects on the activities of GST and AChE. The antifeeding ratio was the highest at 8 h, then decreased, and was the lowest at 16 h. Both GST and AChE activities decreased from 0 h to 48 h in all total ginsenosides treatments but increased at 72 h. Total ginsenosides had antifeeding activity against M. separata larvae and inhibitory effects on the activities of GST and AChE.

1. Introduction

In the long process of adaptation to the environment, plants have developed a chemical response to stress called allelopathy, the release of allelochemicals [1, 2]. Terpenoids are a type of allelochemical and play an important role in regulating plant populations and ecological systems [3, 4].

Ligularia virgaurea secretes terpenoids that inhibit seed germination of other species [5, 6]. Duranta repens extracts have been shown to inhibit oviposition, feeding, and development of Plutella xylostella [7, 8]. Terpenoids from Meliaceae plants have shown insecticidal action against Pieris occidentalis and Leucania separata [9–12].

Ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) is a highly popular and valuable traditional Chinese medicine and tonic. The major ginseng producers of the world are China, Korea, Japan, and Russia [13, 14]. Ginseng can grow for more than one hundred years, but it requires strict ecological conditions that are limited. Wild ginseng populations maintain a specific distance internally between plants [15]. Ginseng has triterpene saponins, and few insects eat its stems or leaves. Ginseng triterpene saponins change the soil microbial population structure and inhibit ginseng seed and seed germination by other species [13–20].

Ginsenosides belong to the group triterpenes and are becoming a popular topic of research in pharmacology, medicine, and clinical drug development in both China and abroad. However, there is little information as to why ginseng synthetizes high levels of ginsenosides (contents of more than 3%) and the significance of ginsenosides for the plant's growth, development, and population dynamics. Ginseng contains a wide variety of triterpene saponins (found in more than 60 species), which suggests that there are a large number of metabolic pathways (including highly evolved metabolic pathways). Based on the scarcity of information, this study discusses the effects of total ginsenosides on the feeding behavior and two enzyme activities of Mythimna separata (Walker) larvae. The results of this study will enable further understanding of the effect of triterpenes on plant population adaptation and evolution. It is also useful to investigate the mechanisms of Chinese herbal medicines and to add to the reference information for phytochemotaxonomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insects

Mythimna separata (Walker) adults were collected at the test base of Jilin Agricultural University in the early summer of 2011. The offspring of these adults were reared on grain sorghum leaves under an LD 16 : 8 h photoperiod at 22 ± 1°C with 70–80% relative humidity and never had contact with insecticides [21].

2.2. Chemicals

The total ginsenosides (purity ≥ 80%, UV method) were purchased from Jilin Hongjiu Biotech Co., Ltd. AChE and GST reagent kits were purchased from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. A Lowry Protein Assay Kit was purchased from Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotech Co., Ltd.

2.3. Bioassay for Feeding Behavior

A leaf disc bioassay was used to test M. separata larvae [22, 23]. The ginsenoside concentrations were 2.0%, 1.0%, and 0.5% (mass fraction (MF)). These concentrations are within the range of ginsenoside levels normally found in P. ginseng. One day prior to the assay, newly molted 4th-instar larvae were placed individually into Petri dishes (9 cm diameter). After starvation for 48 h, 6 excised grain sorghum leaf discs (Φ = 15 mm), soaked in solutions with different concentrations of ginsenosides for 30 min (control discs received distilled water only), were supplied to all larvae. The area of feeding on the leaves was measured every 8 h, and the corresponding antifeeding activity was calculated (nonselective and selective antifeeding ratios). Each test was repeated three times.

2.4. Enzymes Activity Tests

The effects of ginsenosides on larvae of M. separata larvae were tested at concentrations of 2.0%, 1.0%, and 0.5% (MF). The ginsenosides were dissolved with distilled water. Fresh clean grain sorghum leaves were punched into leaf discs with a puncher, and the leaf disc was soaked in different concentrations of ginsenoside solutions for 30 min and air-dried prior to use. The same volume of distilled water without ginsenosides was used for the control group. Fourth-instar larvae were maintained for 48 h without access to food. Larvae with the same weights were then selected and either were allowed to feed on the leaf discs containing ginsenosides or were placed in the control group. The leaves were replaced with the fresh ones every 2 days because of the possible degradation of the ginsenosides. Homogenates for the two enzyme activities (glutathione s-transferase (GST) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity) of M. separata larvae were collected every 24 h. Each test was repeated three times.

Homogenates of the digestive tract of the larvae were prepared as follows. The digestive tract was dissected from individuals of each group and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) to remove the gut contents. To this, 5 mL of cold PBS was added and the solution was centrifuged for 20 min (4°C, 10000 r/min). The supernatant is the homogenate. The protein content of the supernatant fluid was measured using the Lowry Protein Assay Kit staining method [24, 25] with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

GST activity was assessed according to the method of Jaclyn and Min Lü [26, 27] by measuring GSH conjugation with 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB). CDNB activity changes with the substrate concentration in a linear relationship. A visible-ultraviolet spectrophotometer measured absorption at 412 nm to detect product formation. All reactions took place in 0.1 M potassium phosphate-buffer containing 1 mM GSH and 0.01–3 mM CDNB. GST activity was determined according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where Y represents GST activity (μmol/min/mg prot), ODα represents the absorbance of the control group, ODβ represents the absorbance of the experiment group, ODδ represents the absorbance of the reference group, ODε represents the absorbance of the blank group, C σ represents the standard concentration (20 mM), N is the dilution factor of the reaction system (6), T is reaction time (10 min), A is the sample volume (mL), and C prot represents the protein concentration of the sample.

AChE activity was determined using the method of Ellman et al. [28]. The enzyme activity was measured by assessing the increase of yellow color produced from thiocholine when it reacts with the dithiobisnitrobenzoate ion. It is based on the coupling of the following reactions:

| (2) |

The AChE activity was spectrophotometrically measured at 412 nm (UV-754, Shandonggaomi, UV visible-ultraviolet spectrophotometer). The enzyme activities were expressed as μmol/min/mg protein. AChE activity was determined according to the following equation:

| (3) |

In this equation, Y 0 represents AChE activity (μmol/min/mg prot), OD1 represents the absorbance of the experiment group, OD2 represents the absorbance of the control group, OD3 represents the absorbance of the reference group, OD4 represents the absorbance of the blank group, C 0 represents the standard concentration (1 mM), and C prot represents the protein concentration of the sample.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Nonselective and selective antifeeding ratios were calculated according to the following equations:

| (4) |

In these equations, Y 1 represents the nonselective antifeeding ratio (%), Y 2 represents the selective antifeeding ratio (%), S ck represents the average feeding area of the control group (mm), and S represents the average feeding area of the treated group (mm).

The nonselective and selective antifeeding ratios of larvae fed on diets containing different concentrations of ginsenosides were compared using SPSS Statistical 18.0. The effects of ginsenosides on the detoxification enzyme activity of M. separata larvae were also analyzed using SPSS Statistical 18.0. In all statistical tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are presented as the means ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Bioassay for Feeding Behavior

The nonselective antifeeding ratios of 4th-instar M. separata larvae at 8, 16, and 24 h are shown in Table 1. The total ginsenosides appeared to have significant antifeeding activity against M. separata larvae. The nonselective antifeeding ratios at different total ginsenoside concentrations were significantly different from those of the controls at 4, 8, and 12 h. As the total ginsenoside concentration increased, the nonselective antifeeding activity was enhanced. At 8 h, the antifeeding ratios of 2.0%, 1.0%, and 0.5% (MF) were 88.67%, 64.40%, and 47.36%, respectively.

Table 1.

Nonselective antifeeding ratio of different total ginsenoside concentrations on 4th-instar M. separata larvae.

| Concentration of total ginsenosides (%) | 8 h | 16 h | 24 h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average feeding area (mm2) | Nonselective antifeeding ratio (%) | Average feeding area (mm2) | Nonselective antifeeding ratio (%) | Average feeding area (mm2) | Nonselective antifeeding ratio (%) | |

| Control | 1664.67 ± 107.04 a | — | 1770.00 ± 0.00 a | — | 1770.00 ± 0.00 a | — |

| 0.5 | 876.33 ± 333.10 b | 47.36 | 1529.67 ± 28.02 a | 13.58 | 1440.67 ± 89.80 a | 18.61 |

| 1.0 | 592.67 ± 224.13 b | 64.40 | 1524.00 ± 75.29 a | 13.90 | 1408.00 ± 201.27 a | 20.45 |

| 2.0 | 188.67 ± 81.59 c | 88.67 | 757.67 ± 453.24 b | 57.19 | 483.33 ± 358.60 b | 72.69 |

Data are presented as the means ± SE. Means in the same column followed by different letters are significantly different at the level P < 0.05. Prior to analysis of variance (SPSS 18.0), the homogeneity of variance was tested in each statistic test.

The selective antifeeding ratios of the 4th-instar M. separata larvae are shown in Table 2. The 4th-instar M. separata larvae preferred to eat the leaves of the control; however, they did consume a small amount of the treated leaves. The total ginsenosides had significant inhibitory effect on M. separata larvae, and this effect increased with an increase in total ginsenoside concentration.

Table 2.

Selective antifeeding ratio of different total ginsenoside concentrations on 4th-instar M. separata larvae.

| Concentration of total ginsenosides (%) | 8 h | 16 h | 24 h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average feeding area (mm2) | Selective antifeeding ratio (%) | Average feeding area (mm2) | Selective antifeeding ratio (%) | Average feeding area (mm2) | Selective antifeeding ratio (%) | |

| 0.5 | 638.33 ± 34.53 | 34.19 | 450.33 ± 40.45 | 36.62 | 511.33 ± 9.61 | 23.28 |

| Control | 1301.67 ± 77.02 | — | 970.67 ± 52.78 | — | 821.67 ± 39.00 | — |

| 1.0 | 514.67 ± 80.75 | 44.29 | 470.67 ± 24.50 | 32.00 | 527.33 ± 25.74 | 29.23 |

| Control | 1332.33 ± 51.50 | — | 913.67 ± 33.47 | — | 963.00 ± 36.10 | — |

| 2.0 | 267.00 ± 95.79 | 62.49 | 285.33 ± 23.46 | 46.18 | 391.00 ± 22.37 | 42.46 |

| Control | 1156.67 ± 127.38 | — | 775.00 ± 50.48 | — | 968.00 ± 24.06 | — |

Data are presented as the means ± SE. Homogeneity of variance was tested in each statistic test.

3.2. Enzymes Activity Tests

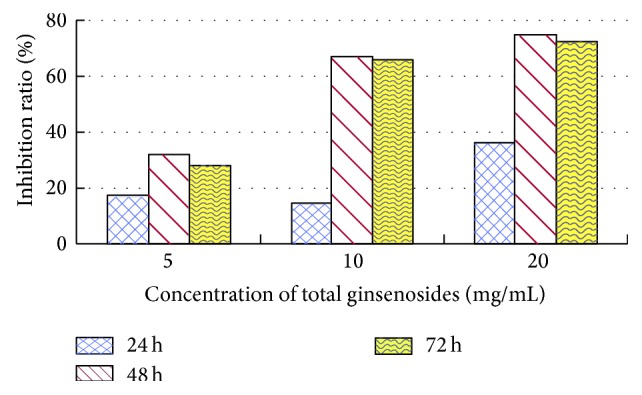

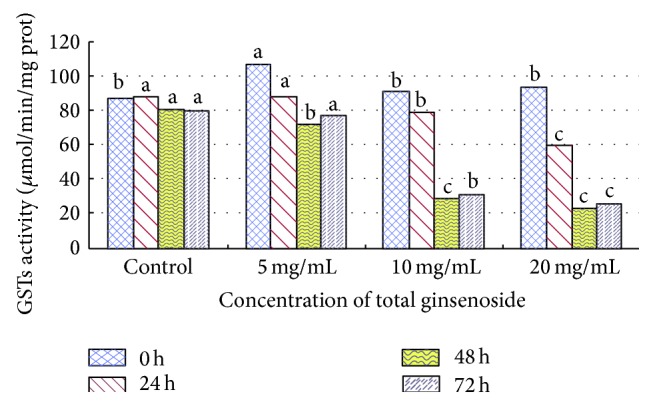

As the total ginsenoside concentration increased, the activity of GST also increased. GST activities first decreased and then increased with the passage of time. The inhibition ratio was the highest at 48 h, with 75.15%, 468.98%, and 31.86% at 2.0%, 1.0%, and 0.5% concentrations, respectively (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Inhibition ratio of total ginsenosides on GST activity in 4th-instar M. separata larvae.

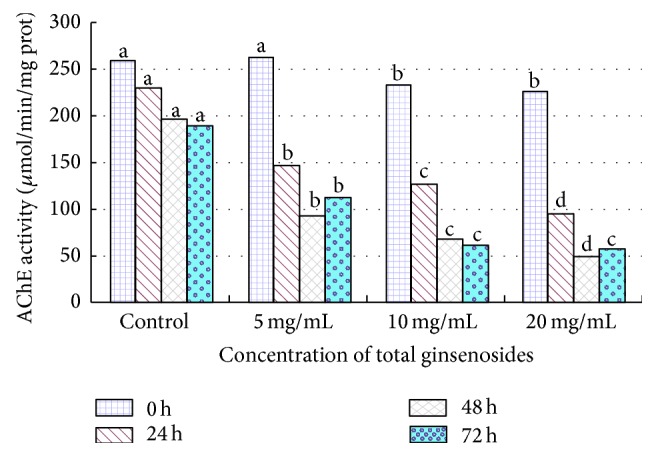

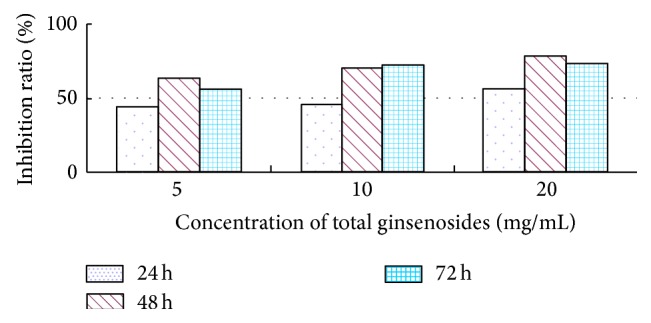

The AChE activity of 4th-instar M. separata larvae was 79.0546 μmol/min/mgprot before feeding on 2.0% (MF) total ginsenosides (see Figure 3); however, the AChE activities were depressed to 61.8998 (inhibition ratio, 21.70%), 31.5114 (inhibition ratio, 60.14%), and 35.0698 (inhibition ratio, 55.64%) μmol/min/mgprot at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively (see Figure 4). The ginsenosides inhibited the AChE activity of 4th-instar M. separata larvae, and the inhibition effect increased with the increase in ginsenoside concentration but did not decrease over time.

Figure 3.

Effect of total ginsenosides on AChE activity in 4th-instar M. separata larvae. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using a one-way ANOVA (SPSS 18.0). Data are means + SD.

Figure 4.

Inhibition ratio of total ginsenosides on AChE activity in 4th-instar M. separata larvae.

4. Discussion

Plant secondary metabolic substances are formed via secondary metabolic pathways and play indispensable roles in the evolution of plants. They have repellency, antifeeding, and toxic effects on phytophagous insects. For example, Momordicin I and II have significant antifeedant activity on second-instar larvae of P. xylostella, and the antifeeding rates were 80.39% and 74.09%, respectively [8]. Plant lectins also have repellency, antifeeding, and toxic effects on phytophagous insects such as caterpillars, tobacco hornworm, cotton leafworm, and beetles [29]. Azadirachtin causes mortality in Nilaparvata lugens (Stal) and destroys its ovarian follicle epithelial cells [30].

We compared the larval feeding behavior of M. separata on a diet containing different concentrations of total ginsenosides (MF: 2.0%, 1.0%, and 0.5%). The total ginsenosides imposed adverse effects on the feeding behavior of M. separata but to different extents (Tables 1 and 2). Comparison with control demonstrates that the consumption of leaves by M. separata was strongly affected by the total ginsenosides. If consumption is reduced, the energy required for physiological activities would also be reduced. Consequently, resistance is then reduced, and physiological metabolism would not be adequate. M. separata are sometimes found near cultivated ginseng; however, they rarely feed on the leaves of ginseng, which is the reason for choosing M. separata for this experiment.

Total ginsenosides inhibited GST and AChE activities of M. separata larvae. If the GST activity was inhibited, the detoxification was reduced. The M. separata changed feeding behaviors and fed on the grain sorghum leaves that were treated with total ginsenosides. In this way, they could reduce the damage from outsiders and protect themselves. It is the same for AChE; their neurotransmission slows down when AChE activity is inhibited and M. separata did feed on a small amount. The total ginsenosides had antifeeding activity against M. separata larvae and inhibitory effects on the activities of GST and AChE. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) play important roles in insect metabolism and resistance to insecticides [31]. This study demonstrates that after treating M. separata with total ginsenosides GST activities decreased. This indicates that total ginsenosides have no toxic effects in vivo and activates the defense system of insects but could also inhibit GST activity. GSTs widely exist in insects and catalyze the nucleophilic reaction of glutathione (GSH) with a variety of electrophilic compounds. GSTs play an important role in exogenous substance biotransformation, drug metabolism, and protection of the organism against oxidative damage [32]. GST activity was inhibited by total ginsenosides, and detoxification was reduced in 4th-instar M. separata larvae (see Figure 1). Thus, they suffered damage from toxic substances and these substances are harmful to living larvae.

Figure 1.

Effect of total ginsenosides on GST activity in 4th-instar M. separata larvae. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using the one-way ANOVA (SPSS 18.0). Data are means + SD.

AChE is an important neurotransmitter enzyme mainly distributed in the brain and central nervous system [33]. AChE is localized at the surface of nerve cells and can decompose neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is released from the nerve endings and guarantees normal nerve conduction [34]. If its activity is inhibited, the acetylcholine released in the synaptic gap cannot be degraded, and insects will have toxicity symptoms and possibly mortality [35]. Several essential oils from aromatic plants, monoterpenes, and natural products have all been shown to be inhibitors of AChE [36]. Pulegone-1,2-epoxide, isolated from a Verbenaceae medicinal plant (Lippia stoechadifolia L. (Poleo)), showed an irreversible inhibition of the AChE in house fly and Madagascar roach [37]. This experiment indicates that the total ginsenosides inhibit AChE activity directly. On the basis of the research mentioned earlier and the comprehensive analysis of our findings, we conclude that the decline of AChE activity in M. separata larvae indirectly indicates damage to nerve cells, which induce AChE photoinactivation and death caused by the disruption of normal nerve conduction. Total ginsenosides have inhibitory allelopathic effects on M. separata, which were beneficial for researching the allelopathic potential of ginsenosides.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31070316, 31100239, and 31200224), the Funded Projects for Science and Technology Development Plan of Jilin (nos. 20110926, 20130206030YY, and 20140520159JH), and the Project supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (no. 2011BAI03B01).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Ai. Hua Zhang and Shi. Qiang Tan are cofirst authors; they contributed equally to the work.

References

- 1.Rice E. L. Allelopathy. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice E. L. Biological Control of Weeds and Plant Diseases: Advances in Applied Allelopathy. Norman, Okla, USA: University of Oklahoma Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng S. L., Nan P. Terpenoids in higher plants and their roles in ecosystems. Chinese Journal of Ecology. 2002;21:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu W. X., Duan S. S., Luo S. M. Ecological characteristic of terpenoids and their allelopathic effects to plants. Journal of South China Agricultural University. 2005;19:108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma R., Wang M., Zhu X., Lu X., Sun K. Allelopathy and chemical constituents of Ligularia virgaurea volatile. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2005;16(10):1826–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma R., Wang M., Zhao K., Guo S., Zhao Q., Sun K. Allelopathy of aqueous extract from Ligularia virgaurea, a dominant weed in psychro-grassland, on pasture plants. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2006;17(5):845–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei H., Hou Y., Yang G., You M. Repellent and antifeedant effect of secondary metabolites of non-host plants on Plutella xylostella . Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2004;15(3):473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling B., Wang G.-C., Ya J., Zhang M.-X., Liang G.-W. Antifeedant activity and active ingredients against plutella xylostella from Momordica charantia leaves. Agricultural Sciences in China. 2008;7(12):1466–1473. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(08)60404-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X. D., Zhao S. H. The toxic effects and mode of azadirachtin on insects. Journal of South China Agricultural University. 1995;17:118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X., Wang X. L., Fen J. T. The development of botanical insecticides—toosendanin. Journal of Northwest Sci-Tech University of Agriculture and Forestry. 1993;21:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W. L., Zhao S. H., Han J., Xu Y. S. Effects of several Insecticidal principles from chinaberry, melia azedarach on the imported cabbage worm and Asiatic corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis . Acta Phytophylacica Sinica. 1992;19:359–364. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y.-L., Wang W.-P. Biological effects of toosendanin, an active ingredient of herbal vermifuge in Chinese traditional medicine. Acta Phytophylacica Sinica. 2006;58(5):397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng-Jie L., Ai-Hua Z., Yong-Hua X., Lian-Xue Z. Allelopathic effects of ginsenosides on in vitro growth and antioxidant enzymes activity of ginseng callus. Allelopathy Journal. 2010;26(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao P. G. Preliminary investigation of wild ginseng in the Northeast. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 1962;6:340–351. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang T. S. Chinese Ginseng. Shenyang, China: Liaoning Science and Technology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang A.-H., Lei F.-J., Xu Y.-H., Zhou G.-X., Zhang L.-X. Effects of ginsenosides on the germinating of ginseng seeds and on the activity of antioxidant enzymes of the radicles of ginseng seedlings in vitro . Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2009;29(9):4934–4941. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang A. H., Lei F. J., Fang S. W., Jia M. H., Zhang L. X. Effects of ginsenosides on the growth and activity of antioxidant enzymes in American ginseng seedlings. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:3217–3223. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A.-H., Lei F.-J., Guo Z.-X., Zhang L.-X. Allelopathic effects of ginseng root exudates on the seeds germination and growth of ginseng and American ginseng. Allelopathy Journal. 2011;28(1):13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y., Liu S.-L., Huang X.-F., Ding W.-L. Allelopathy of ginseng root exudates on pathogens of ginseng. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2009;29(1):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q. J., Ben W. R., Xu L. H. Allelopathic effects of extract from old ginseng soil on seed germination and seedlings growth in rice. Journal of North West A & F University (Natural Science Edition) 2012;40:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma H. C., Sullivan D. J., Bhatnagar V. S. Population dynamics and natural mortality factors of the Oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in South-Central India. Crop Protection. 2002;21(9):721–732. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(02)00029-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan F. M. Chemical Ecology. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen L. Z. Introduction to Entomology Research Methods and Techniques. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartree E. F. Determination of protein: a modification of the lowry method that gives a linear photometric response. Analytical Biochemistry. 1972;48(2):422–427. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen L. Z. Introduction to Entomology Research Methods and Techniques. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodrich J. M., Basu N. Variants of glutathione s-transferase pi 1 exhibit differential enzymatic activity and inhibition by heavy metals. Toxicology in Vitro. 2012;26(4):630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellman G. L., Courtney K. D., Andres V., Jr., Featherstone R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1961;7(2):88–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandenborre G., Smagghe G., Van Damme E. J. M. Plant lectins as defense proteins against phytophagous insects. Phytochemistry. 2011;72(13):1538–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senthil Nathan S., Young Choi M., Yul Seo H., Hoon Paik C., Kalaivani K., Duk Kim J. Effect of azadirachtin on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and histology of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2008;70(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vos R. M. E., van Bladeren P. J. Glutathione S-transferases in relation to their role in the biotransformation of xenobiotics. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1990;75(3):241–265. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(90)90069-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Z. S., Yan Z. G., Du Y. Z., Shang Z. Z. Effect of α-terthienyl on glutathione S-transferases in Helicoverpa armigera and Ostrinia furnacalis larvae. Chinese Journal of Pesticide Science. 2003;15(3):76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J. I., Jung C. S., Koh Y. H., Lee S. H. Molecular, biochemical and histochemical characterization of two acetylcholinesterase cDNAs from the German cockroach Blattella germanica . Insect Molecular Biology. 2006;15(4):513–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin K., Ma E.-B., Xue C.-R., Wu H.-H., Guo Y.-P., Zhang J.-Z. Study on insecticidal activities and effect on three kinds of enzymes by 5-aminolevulinic acid on oxya Chinensis. Agricultural Sciences in China. 2008;7(7):841–846. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(08)60121-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Z. H. Research status and perspectives of insect resistance to insecticides in China. Entomological Knowledge. 2000;37:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaaya E., Rafaeli A. Insecticides Design Using Advanced Technologies. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2007. Essential oils as biorational insecticides—potency and mode of action; pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grundy D. L., Still C. C. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterases by pulegone-1,2-epoxide. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 1985;23(3):383–388. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(85)90100-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]