Abstract

Objectives

In the United States (US), the elderly carry a disproportionate burden of lung cancer. Although evidence-based guidelines for lung cancer care have been published, lack of high quality care still remains a concern among the elderly. This study comprehensively evaluates the variations in guideline-concordant lung cancer care among elderly in the US.

Materials and Methods

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database (2002–2007), we identified elderly patients (aged ≥65 years) with lung cancer (n = 42,323) and categorized them by receipt of guideline-concordant care, using evidence-based guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. A hierarchical generalized logistic model was constructed to identify variables associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care. Kaplan–Meier analysis and Log Rank test were used for estimation and comparison of the three-year survival. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was constructed to estimate lung cancer mortality risk associated with receipt of guideline-discordant care.

Results

Only less than half of all patients (44.7%) received guideline-concordant care in the study population. The likelihood of receiving guideline-concordant care significantly decreased with increasing age, non-white race, higher comorbidity score, and lower income. Three-year median survival time significantly increased (exceeded 487 days) in patients receiving guideline-concordant care. Adjusted lung cancer mortality risk significantly increased by 91% (HR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.82–2.00) among patients receiving guideline-discordant care.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical need to address disparities in receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care among elderly. Although lung cancer diagnostic and management services are covered under the Medicare program, underutilization of these services is a concern.

Keywords: Lung, Cancer, Elderly, Medicare, Disparities, Guidelines, Treatment

1. Introduction

In the United States (US), lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths.1 It causes more deaths than the next three most common cancers combined (colon, breast, and prostate).1 The elderly carry a disproportionate burden of lung cancer, as approximately 81% of those living with lung cancer are age 60 and older.1 This pattern is expected to persist as the estimated number of elderly in the US doubles to approximately 70 million by 2030.2

Although lung cancer in the elderly is associated with poor prognosis, several treatment strategies can cure, or at least prolong survival. Therefore, significant reduction in lung cancer mortality can be achieved if the elderly receive timely and medically effective therapies. To that end, specific strategies for the management and treatment of lung cancer have been recommended in clinical guidelines by American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and others.3–8 These guidelines ensure uniformity of care, and are thought to be capable of improving quality, appropriateness, and cost-effectiveness of care.9 However, studies of clinical practice patterns in the US have documented variations in the management of lung cancer by age, race, education, comorbidity, insurance and hospital type.10–21 Therefore, lack of high-quality-cancer-care is a continuing concern, and it is attributable to variations in the use of appropriate standards of care.22

While studies to date have examined the variations in guideline-concordant lung cancer care, a majority of them have been limited to Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) care,11,18–21 early or late stage cancer care,18–20 cancer care among patients with comorbidities,21 and/or cancer care in the Veterans Affairs setting.19 Furthermore, previous studies have defined guideline-concordant lung cancer care primarily on the bases of the treatment received, and failed to capture the appropriateness of lung cancer staging prior to the receipt of treatment.11,18–21 Specifically, the ACCP guidelines recommend mediastinal lymph node evaluation prior to surgery, as its a determinant of postoperative survival.4 Given the lack of a comprehensive evaluation of the variations in guideline-concordant care, and associated health outcomes, among the elderly patients with NSCLC and Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC), the objectives of this study were to: (1) identify lung cancer treatment patterns among the elderly; (2) identify the proportion of elderly patients with lung cancer receiving guideline-concordant care; (3) identify factors associated with the receipt of guideline-concordant care; (4) determine survival benefits associated with the receipt of guideline-concordant care; and (5) determine lung cancer mortality risk associated with the receipt of guideline-discordant care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study used NCI's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked data files from years 2002–2007. SEER is a consortium of 20 population-based cancer registries covering approximately 28% of the US population and its data are representative of US cancer incidence and mortality.23 Cancer registry data files provided clinical, demographic, cause of death, and initial treatment information for elderly individuals with lung cancer in selected geographic regions. The Medicare administrative data files provided the health service claims (utilization and reimbursement) information for care provided by physicians, inpatient hospital stays, hospital outpatient clinics, home health care agencies, skilled nursing facilities, and hospice programs.

2.2. Study Cohorts

We identified Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years and older, with incident lung cancer diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) codes: C34.0, C34.1, C34.2, C34.3, C34.8, C34.9, and C33.9; American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging (AJCC) Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) Stages: I–IV), between July 1, 2003 and December 31, 2006, in the SEER-Medicare data files.24 Beneficiaries were excluded if they were diagnosed only at death, had a prior malignancy, were enrolled in a managed care plan, or lacked Part A or B of Medicare. This population cohort was used for study objective 1, and for study objectives 2–3 after excluding beneficiaries with Stage IV disease. Given the limited years of follow-up data, for study objectives 4–5, we limited the above population cohort to patients with cancer diagnosis (AJCC TNM Stages I–III) between July 1, 2003 and December 31, 2004, and followed them for three years following the cancer diagnosis to determine lung cancer specific mortality. Beneficiaries with Stage IV disease were excluded in our analysis for study objectives 2–5, as the data source lacked complete treatment information for these patients.

2.3. Accessing Receipt of Guideline-concordant Lung Cancer Care

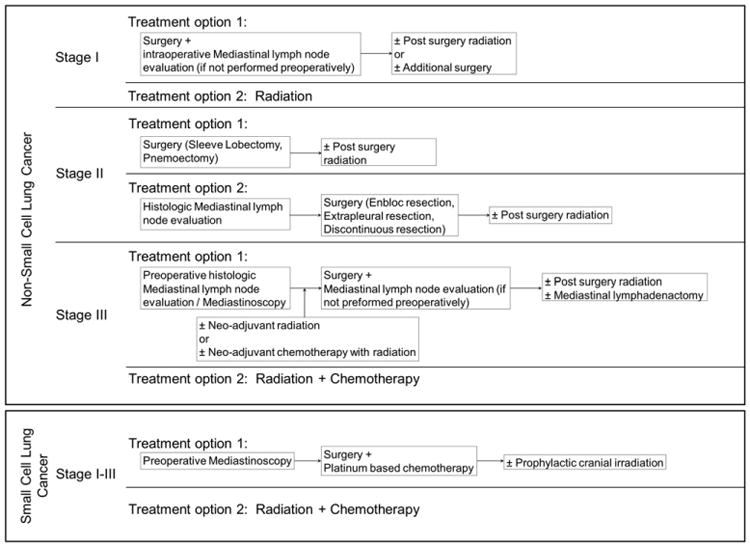

The ACCP evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management of lung cancer were incorporated in an algorithm and used to determine receipt of guideline-concordant care (see Fig. 1).4 Specifically, patients were followed for one year following their cancer diagnosis to determine receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care. Lung cancer treatments and procedures were identified from Medicare claims data using appropriate International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and revenue center codes (Appendix A).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm adapted from American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management of lung cancer published in January, 2003, and used to determine receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care.

2.4. Dependent Variables

Treatment patterns were categorized as ‘surgery only’, ‘radiation only’, ‘chemotherapy only’, ‘combination treatment’, or ‘no treatment’. The primary outcome of interest, receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care, was categorized as ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Survival time in days was calculated from the date of cancer diagnosis to the date of death or the three-year follow-up cutoff date, whichever came first. SEER only provides the month and year of cancer diagnosis: therefore we approximated the date of cancer diagnosis by using the earliest Medicare claim date that had a lung cancer diagnosis code, which was in the SEER reported diagnosis month. This approximation is appropriate given the high level of agreement (∼90%) within one month of diagnosis between the SEER diagnosis date and the first Medicare claim date with a cancer diagnosis.25 If the beneficiary had no Medicare claim with a lung cancer diagnosis code, the earliest date from any Medicare claim in the SEER reported diagnosis month was used. Finally, among patients with no Medicare claim in the SEER reported diagnosis month, the date of diagnosis was approximated as the 15th day of that month. Date of death was identified from Medicare enrollment records. To estimate lung cancer specific survival, patients not found to be deceased by the cutoff date, or who died due to causes other than lung cancer were censored at that time and considered to be alive.

2.5. Covariates

Based on prognostic significance, covariates included lung cancer type and stage, age at diagnosis, gender, race, urban–rural residence, comorbidity, and measures of socio-economic status. Lung cancer type was categorized based on cell histology. Patients with ICD-O histology codes 8000–8040 or 8046–9989 were categorized as having NSCLC disease, and those with codes 8041–8045 were categorized as having SCLC disease. Lung cancer stage was categorized based on AJCC TNM staging system.24 Age at diagnosis was categorized as 66–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years, and 80 years and older. Race was categorized as ‘White’ or ‘Non-white’. Urban-rural residence was categorized as ‘Metro’, ‘Urban’, or ‘Rural’, using the Rural–Urban Continuum codes. Comorbidity was estimated using a modified Charlson comorbidity score, based on inpatient claims from the year preceding the cancer diagnosis.26–28 This method of creating a weighted comorbidity score has previously been reported and used for both outcomes and patterns of care analysis.26–28 Given the lack of individual socio-economic measures in our data source, median household income and the percentage of individuals with some college education in the census tract of residence, were used as markers of socio-economic status.

2.6. Data Analysis

Pearson chi-square tests were used to determine unadjusted associations between categorical variables of interest. A hierarchical generalized logistic model was constructed with PROC GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.2 to identify factors associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care among elderly patients. In the model, the estimated probability of a patient receiving guideline-concordant care conditioned on a set of predictor variables was modeled. The model treated census tract as a random effect to account for potential correlation among patients within the same county. Non-parametric estimates of the survivor function by receipt of guideline-concordant care were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival differences were assessed using log-rank test. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was constructed to estimate lung cancer mortality risk associated with receipt of guideline-discordant care among elderly patients. To evaluate the proportional hazards assumption, we plotted smoothed Schoenfeld residuals against time and found no evidence of a systematic deviation from proportional hazards in the model. Variances in models were adjusted to account for patient clustering at the census tract level by the use of the robust inference of Lin and Wei.29 Analysis were performed with SAS (version 9.2; Cary, NC). The study was approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 42,323 patients from the SEER-Medicare database. Table 1 shows the distribution of clinical and socio-demographic characteristics of these patients by type of lung cancer. The majority of the patients had NSCLC and were diagnosed with late-stage disease. Compared to patients with SCLC, patients with NSCLC were older, male, resided in metro areas, and had lower comorbidity scores (p ≤ 0.05). However, a majority of the patients with SCLC were diagnosed at later stages, as compared to patients with NSCLC (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of continuously enrolled Medicare Fee-for-service beneficiaries with incident lung cancer diagnosis in the United States, July-2003 through December-2006.

Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare linked data files, 2002–2007.

| Characteristics | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Non-small cell lung cancer | Small cell lung cancer | |

| Overall, n (%) | 36,417 (86.0) | 5906 (14.0) |

| AJCC-TNM Stagea | ||

| I | 20.6 | 5.1 |

| II | 4.7 | 2.2 |

| III | 28.4 | 29.8 |

| IV | 46.2 | 62.9 |

| Age (years)a | ||

| 66–69 | 19.2 | 24 |

| 70–74 | 25.8 | 28.8 |

| 75–79 | 25.9 | 26.2 |

| ≥80 | 29.1 | 21 |

| Gendera | ||

| Male | 51.9 | 47.4 |

| Female | 48.1 | 52.6 |

| Racea | ||

| Non-white | 13.3 | 9.2 |

| White | 86.7 | 90.8 |

| Urban–rural residencea | ||

| Metro | 83.1 | 80.2 |

| Urban | 14.9 | 17.2 |

| Rural | 2 | 2.6 |

| Comorbidity, Charlson scorea | ||

| 0 | 31.7 | 29.7 |

| 1 | 28.5 | 28.8 |

| ≥2 | 39.8 | 41.5 |

AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; TNM = Tumor Node Metastasis.

Association between characteristic and cancer type among beneficiaries; Chi-square tests (p ≤ 0.05).

3.2. Treatment Patterns

Table2 shows the descriptive characteristics of patients by the type of treatment received. Almost one-third of all patients (33.4%) received no treatment for lung cancer. Among those patients receiving any treatment, the most common regimens included combination therapy (27.9%) followed by radiotherapy (15.9%). Significant variations in treatment patterns were observed by lung cancer type, stage, age, gender, race, urban–rural residence, comorbidity score, and year of diagnosis. In general, surgery or combination therapy was the most common treatment choice in patients with early stage disease. Specifically, a significant proportion of patients with early stage NSCLC received surgical treatment.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics by type of treatment among continuously enrolled Medicare Fee-for-service beneficiaries with incident lung cancer diagnosis in the United States, July 2003 through December 2006.

Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results—Medicare linked data files, 2002–2007.

| Characteristics | Proportion (%) a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| No treatment | Surgery only | Radiation only | Chemotherapy only | Combination treatment | |

| Overall, n (%) | 14,137 (33.4) | 4172 (9.9) | 6730 (15.9) | 5461 (12.9) | 11,832 (27.9) |

| Cancer typeb | |||||

| NSCLC | 34.1 | 11.4 | 17.1 | 11.2 | 26.2 |

| SCLC | 28.9 | 0.5 | 8.4 | 23.6 | 38.7 |

| AJCC TNM stageb | |||||

| I | 23.7 | 41 | 12.7 | 3.6 | 19 |

| II | 17 | 19.7 | 10.7 | 4.9 | 47.8 |

| III | 32.5 | 3.5 | 14.5 | 13.1 | 36.5 |

| IV | 39.1 | 0.8 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 24.5 |

| Age (years)b | |||||

| 66–69 | 23 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 40.5 |

| 70–74 | 26.1 | 10.4 | 14.7 | 13.7 | 35 |

| 75–79 | 32.5 | 11.3 | 15.9 | 13.9 | 26.5 |

| 80 or more | 48.5 | 8.1 | 19.2 | 10.6 | 13.7 |

| Genderb | |||||

| Male | 33.4 | 8.8 | 15.9 | 13 | 28.8 |

| Female | 33.4 | 11 | 15.9 | 12.8 | 27 |

| Raceb | |||||

| Non-white | 37.9 | 7 | 17.6 | 12.4 | 25.1 |

| White | 32.7 | 10.3 | 15.7 | 13 | 28.3 |

| Urban–rural residenceb | |||||

| Metro | 32.9 | 10.1 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 27.8 |

| Urban | 36.2 | 8.7 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 28.5 |

| Rural | 34.2 | 8.2 | 14.8 | 13.6 | 29.2 |

| Comorbidity, Charlson scoreb | |||||

| 0 | 33.1 | 7.9 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 31 |

| 1 | 29.4 | 11.2 | 15.6 | 13.2 | 30.6 |

| 2 or more | 36.6 | 10.4 | 16.9 | 12.5 | 23.6 |

| Year of diagnosisb | |||||

| 2003 (July–Dec) | 33.6 | 9.4 | 15.2 | 13.3 | 28.5 |

| 2004 | 32.2 | 9.5 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 30.5 |

| 2005 | 33.2 | 9.7 | 15 | 13.5 | 28.6 |

| 2006 | 34.8 | 10.6 | 18.7 | 11.6 | 24.4 |

NSCLC = Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, SCLC = Small Cell Lung Cancer, AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM = Tumor Node Metastasis.

Proportions reported are row percentages of beneficiaries receiving particular treatment.

Association between characteristic and type of treatment among beneficiaries; Chi-square tests (p ≤ 0.05).

3.3. Receipt of Guideline-concordant Lung Cancer Care

Table 3 shows the descriptive characteristics of patients by receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care. Less than half of all patients (44.7%) received guideline-concordant lung cancer care in the study population. The proportion of patients receiving guideline-concordant care was higher among those with SCLC diagnosis as compared to those with NSCLC diagnosis. While these proportions increased with increase in stage of diagnosis among patients with SCLC, the opposite was true in patients with NSCLC. Overall, patients receiving guideline-concordant care were mostly younger and had lower comorbidity score (p ≤ 0.05). Race and urban–rural residence were also associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care.

Table 3.

Descriptive characteristics by receipt of guideline-concordant care among continuously enrolled Medicare Fee-for-service beneficiaries with incident lung cancer diagnosis (Stages I–III) in the United States, July-2003 through December-2006.

Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare linked data files, 2002–2007.

| Characteristics | Guideline-concordant care a | Guideline-discordant care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| No. | % b | No. | % b | |

| Overall | 9736 | 44.7 | 12,048 | 55.3 |

| NSCLC | ||||

| Stage I | 4188 | 55.7 | 3332 | 44.3 |

| Stage II | 844 | 49.1 | 876 | 50.9 |

| Stage III | 3653 | 35.3 | 6701 | 64.7 |

| Stages I–III | 8685 | 44.3 | 10,909 | 55.7 |

| SCLC | ||||

| Stage I | 130 | 43.2 | 171 | 56.8 |

| Stage II | 59 | 45.7 | 70 | 54.3 |

| Stage III | 862 | 49 | 898 | 51 |

| Stages I–III | 1051 | 48 | 1139 | 52 |

| Age (years)c | ||||

| 66–69 | 2325 | 55.7 | 1849 | 44.3 |

| 70–74 | 2899 | 50.4 | 2851 | 49.6 |

| 75–79 | 2576 | 45 | 3152 | 55 |

| ≥80 | 1936 | 31.6 | 4196 | 68.4 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4930 | 44.6 | 6130 | 55.4 |

| Female | 4806 | 44.8 | 5918 | 55.2 |

| Racec | ||||

| Non-white | 1090 | 39.7 | 1654 | 60.3 |

| White | 8646 | 45.4 | 10,394 | 54.6 |

| Urban–rural residencec | ||||

| Metro | 8101 | 45.3 | 9793 | 54.7 |

| Urban | 1446 | 42 | 1995 | 58 |

| Rural | 189 | 42.1 | 260 | 57.9 |

| Comorbidity, Charlson scorec | ||||

| 0 | 2820 | 46 | 3314 | 54 |

| 1 | 3040 | 48.2 | 3265 | 51.8 |

| ≥2 | 3876 | 41.5 | 5469 | 58.5 |

Guideline-concordant care determined using American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management of lung cancer, January 2003.

Row percentages.

Association between beneficiary characteristics and receipt of guideline-concordant care; Chi-square test (p ≤ 0.05).

3.4. Factors Associated with Receipt of Guideline-concordant Lung Cancer Care

Controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, age remained a strong predictor of receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care (Table 4). Compared to patients aged 80 and older, those aged 66–69 years were more than twice as likely to receive guideline-concordant care, and the odds gradually decreased with increase in age.

Table 4.

Factors associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care among continuously enrolled Medicare Fee-for-service beneficiaries with incident diagnosis of lung cancer (Stages I–III) in the United States (US), July-2003 through December-2006.

Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare linked data files, 2002–2007.

| Characteristics | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept (p-value) | 0.15 | – |

| Age (years) | ||

| 66–69 | 2.66*** | 2.44–2.89 |

| 70–74 | 2.13*** | 1.97–2.31 |

| 75–79 | 1.79*** | 1.66–1.93 |

| ≥80 | Reference | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 |

| Female | Reference | |

| Race | ||

| Non-white | 0.79*** | 0.72–0.86 |

| White | Reference | |

| Urban–rural residence | ||

| Metro | 1.11 | 0.90–1.38 |

| Urban | 0.99 | 0.79–1.22 |

| Rural | Reference | |

| Comorbidity, Charlson score | ||

| 0 | 1.14*** | 1.06–1.21 |

| 1 | 1.27*** | 1.18–1.35 |

| ≥2 | Reference | |

| Percentage with some college education (%)a | ||

| 0.0–0.10 | 1 | 0.02–45.32 |

| 0.11–0.20 | 1.09 | 0.05–8.79 |

| ≥0.21 | Reference | |

| Median household income ($)a | ||

| 0–25,000 | 0.75*** | 0.67–0.84 |

| 25,001–50,000 | 0.85** | 0.77–0.94 |

| ≥50,001 | Reference |

Statistical significance:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001.

Guideline-concordant care determined using American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management of lung cancer, January, 2003.

Model: N = 21,784, Fit Statistics: -2 restricted log pseudo-likelihood = 93427.13, Covariance parameter estimates: Intercept = county, estimate = 0.56, standard error = 0.011.

Census tract level measure.

Race, comorbidity score, and median household income were the other significant predictors of receipt of guideline-concordant care. Specifically, patients of non-white race were 21% (Odds ratio = 0.79, 95% Confidence interval (CI) = (0.72–0.86); p < 0.001) less likely to receive guideline-concordant care as compared to whites. Similarly, the likelihood of receipt of guideline-concordant care decreased with decrease in median household income. However, gender differences in the likelihood of receipt of guideline-concordant care were not observed.

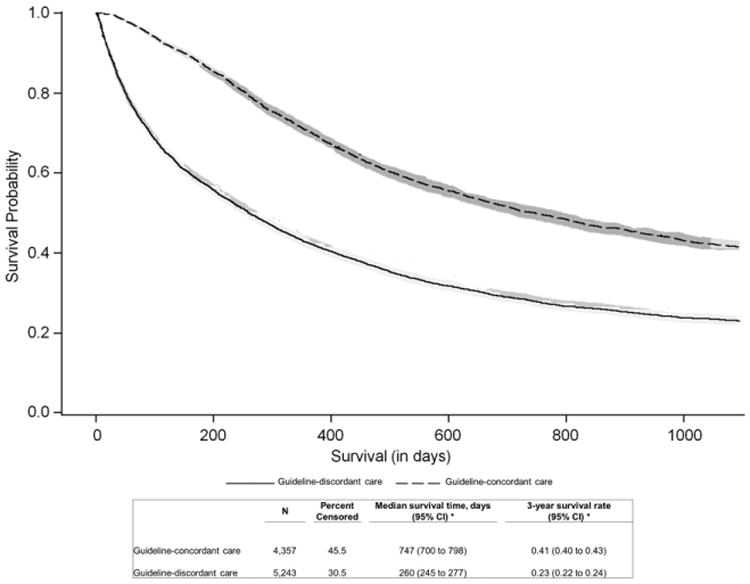

3.5. Survival Benefits Associated with Receipt of Guideline-concordant Lung Cancer Care

Three-year survival rates and median survival times were significantly greater among patients receiving guideline-concordant lung cancer care (Fig. 2). Specifically, three-year median survival time was exceeded by 487 days among patients receiving guideline-concordant care. Stratified analysis also showed significant survival benefit with receipt of guideline-concordant care among patients with NSCLC and patients with SCLC (results not shown here).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates with 95% confidence limits by receipt of guideline-concordant care among continuously enrolled Medicare Fee-for-service beneficiaries with incident lung cancer diagnosis (Stages I–III) in the United States, July 2003 through December 2004. Curves (unadjusted) show cause-specific mortality.

3.6. Lung Cancer Mortality Risk Associated with Receipt of Guideline-discordant Lung Cancer Care

In the Cox proportional hazards model, the adjusted lung cancer mortality risk was significantly higher among patients receiving guideline-discordant care, relative to those receiving guideline-concordant care (Hazard ratio (HR) = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.82–2.00; p < 0.001). Specifically, lung cancer mortality risk among patients receiving guideline-discordant care increased by 91%. Other factors independently associated with higher lung cancer specific mortality risk included SCLC diagnosis, late stage disease, older age, male sex, white race, higher comorbidity score, and lower median household income (results not shown here).

4. Discussion

In 1990, the seminal report Ensuring Quality Cancer Care by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended the need for cancer disparities research so as to optimize the delivery of cancer care for all Americans.22 Despite the fervor generated by this report, lung cancer disparities still exist in the US and can be attributed to variations in lung cancer care. To that end, this population-based analysis studied the patterns of guideline-concordant lung cancer care and associated health outcomes among elderly patients with lung cancer in the US.

Lung cancer treatment patterns varied significantly among elderly patients in the US. Despite the availability of different treatment options, many patients did not receive any treatment. Majority of these patients had either NSCLC diagnosis, late stage disease, and/or were of old age. Therefore, disease severity may partly explain the lack of treatment among these elderly patients. Among patients receiving treatment, surgery was most commonly received among those with NSCLC diagnosis and/or with early stage disease. On the other hand, chemotherapy was most commonly received among patients with SCLC diagnosis and/or with late stage disease. The pattern is expected as lung cancer type and stage dictates the choice of appropriate treatment.4

Overall, guideline-concordant lung cancer care was only received by less than half of all patients, and this proportion was lower than that reported in previous studies.11,18–21 The comprehensive nature of this study, capturing the appropriateness of lung cancer staging prior to the receipt of treatment, may partly explain the differences in finding. Receipt of guideline-concordant care was also found to vary by lung cancer type and stage. While the rates of guideline-concordant care decreased with increase in stage of diagnoses among patients with NSCLC, the opposite was true among patients with SCLC. Compared to NSCLC, SCLC grows and spreads more quickly, and without treatment it has the most aggressive clinical course. Therefore, an aggressive treatment approach in patients with SCLC may help explain the observed findings.

The rates of guideline-concordant lung cancer care significantly decreased with increase in age at diagnosis. Furthermore, age at diagnosis was also found to be a significant predictor of receipt of guideline-concordant care. This finding is similar to that reported in prior studies, and may be attributed to disease severity and comorbidity burden in patients, physician treatment choice, and/or individual treatment preferences, especially during end of life care.11,12,15,16 Comorbid illness is common among elderly patients and it significantly impacts the choice of treatment. Also, given the impact of treatment on patient morbidity and quality of life, physicians may be conservative in their choice of curative treatment for elderly patients, as compared to younger patients. While gender differences in receipt of guideline-concordant care were not observed, differences in receipt of guideline-concordant care by race and comorbidity were seen. Similar to results found in a prior study, comorbidity was inversely associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care.11 This may be attributed to either less aggressive treatment approach by physicians in patients with higher comorbidity burden, or to individual preferences of patients seeking to avoid aggressive treatments in favor of a better quality of life. Median household income was the only socio-economic factor found to be associated with receipt of guideline-concordant care.

Receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care significantly improved survival outcomes among elderly patients in the population. In stratified analysis, this survival benefit was also observed among patients with NSCLC and SCLC. Furthermore, the adjusted lung cancer mortality risk was found to be significantly higher among patients receiving guideline-discordant care. These findings justify the need for uniformity in cancer care through universal adoption of evidence-based guidelines in lung cancer management and treatment. The data from this study also highlights opportunities for improvement in cancer care among elderly patients.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Although we used cancer registry linked claims data, an inherent limitation of using administrative claims data for epidemiologic studies is the possibility of misclassification as a result of coding errors.30 However, claims data have been evaluated for their utility as a source of epidemiologic or health services information in patients with cancer.30 Increasing the use of these types of data to assess the quality of cancer care has also been identified as a priority by the IOM. The results of this study are generalizable to the Medicare Fee-for-service (FFS) population aged 66 years and older, as data for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the managed care plan were not available for this study. Continuous enrollment in Medicare Part A and B was necessary for this study, therefore beneficiaries with non-continuous/intermittent enrollment were excluded. Information on care received by beneficiaries outside of the Medicare system, or through non-Medicare providers, was not available for this study.

We acknowledge that various clinical guidelines have been published for lung cancer diagnosis and management, each with recommendations that are more or less the same.3–8 While these guidelines are meant to be followed in patients who are medically fit, they may not be applicable in patients who are medically unfit, thus highlighting the importance of geriatric patient assessment by physicians prior to treatment. For the purpose of this study, we chose ACCP guideline for lung cancer management and treatment, as it is the most comprehensive of all available guidelines.4 However, it must be noted that the ACCP guidelines are not as specific to the elderly patient population as are the more recently published guidelines by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—Elderly Task Force.8 The algorithm adapted from the guideline takes into account the limitations of our data source. Specifically, information on various lung function test results and lung performance scores were not available in our data source, and were not considered in our analysis. Furthermore, our estimates of proportion of patients receiving guideline-concordant care may be biased slightly upward as we included patients who received guideline-concordant care and additional unproven therapies. We also acknowledge that our definition of receipt of guideline-concordant care may be too narrow, and that given the heterogeneity of patients seen by physicians, ‘no treatment’ may still be considered as appropriate care. Nonetheless, our definition of receipt of guideline-concordant care provides a conceptual framework to assess and compare patterns of care that were prevalent during the years 2002–2007. Future studies can overcome the barriers seen in this study by collecting data on physician treatment choice, patient treatment preferences, clinical test information, and individual-level measures of socio-economic status.

In summary, variations in lung cancer care among elderly patients continue to exist in the nation. Although evidence-based clinical guidelines for management and treatment of lung cancer have been published by various organizations, their adoption in clinical practice is found to be limited. The resulting disparities in receipt of guideline-concordant lung cancer care partly explain the disproportionate burden of this disease among the elderly. Underutilization of lung cancer diagnostic and management services among Medicare beneficiaries is also a cause for concern, as these services are covered under the Medicare program. Interventions aimed at reducing these observed disparities in lung cancer care can help to improve health outcomes among elderly patients in the US.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Grant # 1R24HS018622-01 [PI: S. Madhavan]). Research reported in this publication was also partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM104942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A

List of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and revenue center codes, used to identify lung cancer specific treatments and procedures in Medicare claim data files

Surgery:

Lobectomy: ICD-9 (324,3240,3249,3241) CPT (32480,32482,32486,32663)

Pneumonectomy: ICD-9 (325,3250,3259,3250) CPT (32440,32442,32445,32488)

Segmentectomy: ICD-9 (323,3230,3239,3230) CPT (32484,32663)

Wedge resection: ICD-9 (3229,3220,3220) CPT (32500,32657)

Other surgery: ICD-9 (329,3290,3399,344,3440,3409,3228)

Mediastinal lymphadenectomy: ICD-9 (4029), CPT (38746)

En bloc resection: ICD-9 (326,3260) CPT (32520,32522,32525)

Extrapleural resection: ICD-9 (3401) CPT (32310,32320,32656)

Discontinuous resection: ICD-9 (344,3440)

Chemotherapy:

ICD-9 (Diagnosis codes: V5811,V581,V662,V672; Procedure codes: 9925,9928, 0015,3492)

CPT (96400,96405,96406,96408,96410,96412,96414,96420, 96422,96423,96425, 96440,96445,96450,96520,96530,96542, 96545,96549)

HCPCS (Q0083,Q0084,Q0085,G0355,G0356,G0357,G0358, G0359,G0360,G0361, G0362,G0363, G9021-G9032)

Chemotherapy drug codes: Cisplatin, HCPCS (J9060, J9062); Paclitaxel, HCPCS (J9265); Vinorelbine, HCPCS (J9390); Gemcitabine, HCPCS (J9201); Docetaxel, HCPCS (J9170); Carboplatin, HCPCS (J9045)

Radiation:

ICD-9 (Diagnosis code: V580,V661,V671; Procedure code: 9229,9221,9222, 9223,9224,9225,9226,9227,9228)

CPT (77401,77402,77403,77404,77406,77407,77408,77409, 77411,77412,77413,77414,77416,77417,77418,77427,77431, 77432,77470, 77499,77520,77523,77750-77799)

HCPCS (G0256,G0261)

Revenue center (0330,0333)

Mediastinal lymph node evaluation:

Preoperative: ICD-9 (3425,3422) CPT (39400, 32405, 39000, 39010)

Intraoperative: ICD-9 (3426,325,3250) CPT (39200, 39220, 32662, 38746)

Mediastinoscopy:

ICD-9 (3422)

CPT (39000,39010,39400)

Footnotes

Disclosures and Conflict of Interests Statements: No disclosures.

Author Contributions: Conception and Design: PA Nadpara, SS Madhavan, C Tworek, U Sambamoorthi, M Hendryx, M Almubarak.

Data Collection: PA Nadpara, SS Madhavan.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: PA Nadpara, SS Madhavan, C Tworek.

Manuscript Writing: PA Nadpara, SS Madhavan, C Tworek.

Approval of Final Article: PA Nadpara, SS Madhavan, C Tworek, U Sambamoorthi, M Hendryx, M Almubarak.

References

- 1.U.S. National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–2008. [Accessed on: October 1, 2014]; Available at, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/index.html.

- 2.Day JC. Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995–2050. US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 25–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, Sause W, Smith TJ, Baker S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 15;22(2):330–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diagnosis and management of lung cancer: Chest. 1 Suppl. Vol. 123. American College of Chest Physicians; Jan, 2003. ACCP evidence-based guidelines; p. D-337S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Aug;15(8):2996–3018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2996. Adopted on May 16, 1997 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Cancer Society. Lung Cancer: Treatment Guidelines for Patients. [Accessed on: October 1, 2014];2001 Dec;Version 1 Available at, http://www.nccn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Institute. Physician Data Query Cancer Information Summaries. [Accessed on: October 1, 2014]; Available at, http://www.nci.nih.gov/cancerinfo/pdf/treatment/non-small-cell-lung/healthprofessional/

- 8.Pallis AG, Gridelli C, Wedding U, Faivre-Finn C, Veronesi G, Jaklitsch M, et al. Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert's opinion paper: EORTC Elderly Task Force, Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1270–1283. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field M, Lohr Kn, editors. Institute of Medicine Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinial practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Given CW. Treatment and survival differences in older Medicare patients with lung cancer as compared with those who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Nov 1;26(31):5067–5073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potosky AL, Saxman S, Wallace RB, Lynch CF. Population variations in the initial treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Aug 15;22(16):3261–3268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Venditti LN, Neumann PJ, Gelber RD, Weinstein MC, Potosky AL, et al. Who gets chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer? Chest. 2000 May;117(5):1239–1246. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry WA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. Ten-year survey of lung cancer treatment and survival in hospitals in the United States: a national cancer data base report. Cancer. 1999 Nov 1;86(9):1867–1876. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991101)86:9<1867::aid-cncr31>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, Begg CB. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999 Oct 14;341(16):1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillner BE, McDonald MK, Desch CE, Smith TJ, Penberthy LT, Retchin SM. A comparison of patterns of care of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma patients in a younger and Medigap commercially insured cohort. Cancer. 1998 Nov 1;83(9):1930–1937. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981101)83:9<1930::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith TJ, Penberthy L, Desch CE, Whittemore M, Newschaffer C, Hillner BE, et al. Differences in initial treatment patterns and outcomes of lung cancer in the elderly. Lung Cancer. 1995 Dec;13(3):235–252. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slatore CG, Au DH, Gould MK. An official American Thoracic Society systematic review: insurance status and disparities in lung cancer practices and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Nov 1;182(9):1195–1205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-038ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salloum RG, Smith TJ, Jensen GA, Lafata JE. Factors associated with adherence to chemotherapy guidelines in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012 Feb;75(2):255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, Bozeman SR, McNeil BJ. Reasons for underuse of recommended therapies for colorectal and lung cancer in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2012 Jul 1;118(13):3345–3355. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zornosa C, Vandergrift JL, Kalemkerian GP, Ettinger DS, Rabin MS, Reid M, et al. First-line systemic therapy practice patterns and concordance with NCCN guidelines for patients diagnosed with metastatic NSCLC treated at NCCN institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012 Jul 1;10(7):847–856. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JY, Moore PC, Steliga MA. Do HIV-infected non-small cell lung cancer patients receive guidance-concordant care? Med Care. 2013 Dec;51(12):1063–1068. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewitt M, Simone JV, editors. Ensuring the Quality of Cancer Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002 Aug;40(8 Suppl):IV–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mountain CF. Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest. 1997 Jun;111(6):1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agreement between the SEER & Medicare claims regarding the month of diagnosis. [Accessed on: October 1, 2014]; Available at, http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/considerations/date.html.

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 Jun;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993 Oct;46(10):1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989 Dec;84(408):1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993 Aug;31(8):732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]