Abstract

Introduction

Most evidence-based interventions to improve fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption target individual behaviors and family systems; however, these changes are difficult to sustain without environmental support. This paper describes an innovative social and structural food store-based intervention to increase availability and accessibility of FVs in tiendas (small-to medium-sized Latino food stores) and purchasing and consumption of FVs among tienda customers.

Methods

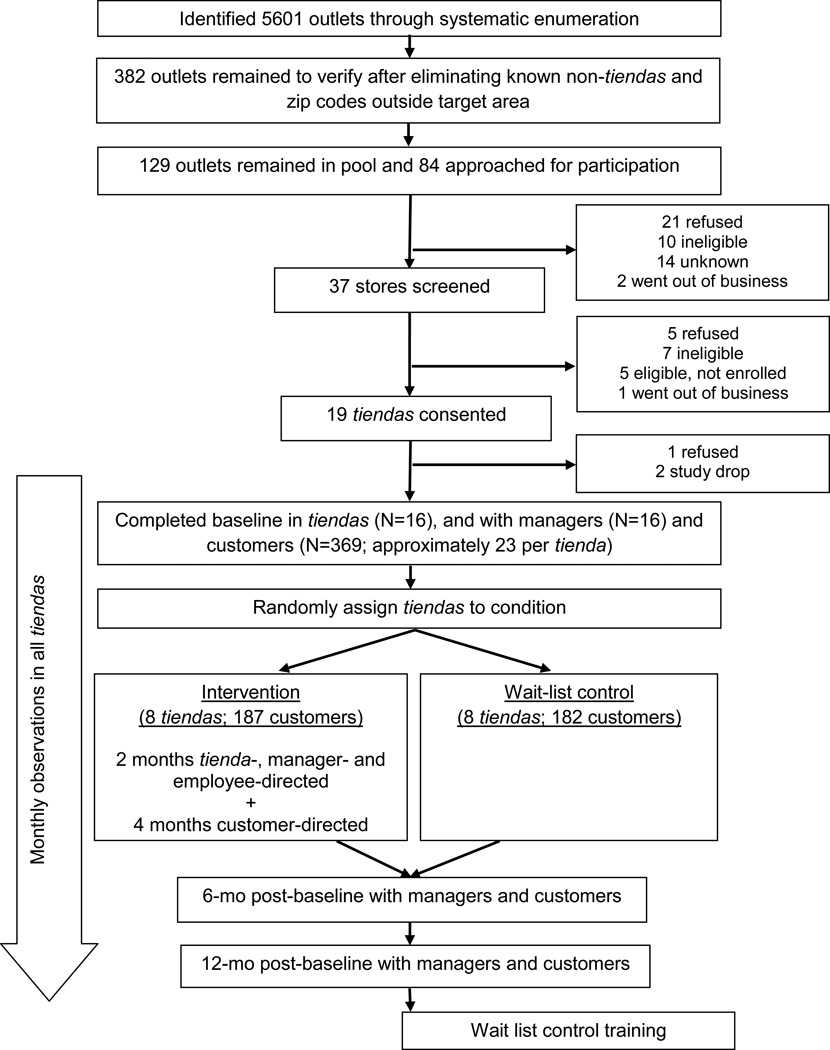

Using a cluster randomized controlled trial with 16 tiendas pair-matched and randomized to an intervention or wait-list control condition, this study will evaluate a 2-month intervention directed at tiendas, managers, and employees followed by a 4-month customer-directed food marketing campaign. The intervention involves social (e.g., employee trainings) and structural (e.g., infrastructure) environmental changes. Three hundred sixty-nine customers (approximately 23 per tienda) serve on an evaluation cohort and complete assessments (interviews and measurements of weight) at 3 time points: baseline, 6-months post-baseline, and 12-months post-baseline. The primary study outcome is customer-reported daily consumption of FVs. Manager interviews and monthly tienda audits and collection of sales data will provide evidence of tienda-level intervention effects, our secondary outcomes. Process evaluation methods assess dose delivered, dose received, and fidelity.

Results

Recruitment of tiendas, managers, employees, and customers is complete. Demographic data shows that 30% of the customers are males, thus providing a unique opportunity to examine the effects of a tienda-based intervention on Latino men.

Conclusions

Determining whether a tienda-based intervention can improve customers’ FV purchasing and consumption will provide key evidence for how to create healthier consumer food environments.

Keywords: food store, tiendas, environmental change, fruits and vegetables, employee training, Latino

Introduction

Few members of the US population meet dietary guidelines for fruits (Fs; 33%) and vegetables (Vs; 26%) [1]. US Latinos are more likely to meet guidelines for F compared with non-Hispanic whites (37% versus 31%, respectively). However, the same is not true for V (20% versus 28%, respectively) [1]. Latino men exhibit even greater disparities in FV consumption with fewer than 20% of Latino men consuming FVs five or more times per day compared with 28% of Latinas [2]. Compounding this risk, research indicates that less acculturated US Latinos (e.g., Spanish- versus English-language use) consume fewer servings of FVs with each additional year in the US [3].

Evidence-based interventions to improve FV consumption have focused on the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels of the Social Ecological framework (SEF) by targeting individual behaviors and family systems [4, 5], for example, by improving food preparation skills [6] or developing effective family communication and planning around meals [7]. However, these individual and family changes are hard to sustain without environmental support. As a framework designed to consider multiple sources of influence on health [8–11], the SEF also recognizes the importance of policy-level changes, such as those that improve access to healthy foods [12,13]. Policies that have the potential to create community change are often considered more sustainable approaches for promoting healthy eating [14], but these are often targeted to a subset of the population, for example, those who qualify for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [15]. Given these limitations, researchers and practitioners have argued for identifying effective strategies for changing the consumer food environment [14,16]. Interventions that target change at the community-level, specifically within the food retail environments frequented by Latinos, are missing from this research [17].

Food store interventions are an innovative approach for improving the consumer food environment, as well as improving health-related attitudes and behaviors [18,19], including grocery purchasing. In addition, store-based interventions can be implemented with fidelity [20]. However, evidence from randomized controlled trials is lacking on feasible and effective methods for changing customers’ FV consumption. The El Valor de Nuestra Salud (or “El Valor”; translated as “The Value of Our Health”) study fills this gap in research; it tests a multi-component intervention in small-to-medium-sized ethnic food stores catering to a Latino clientele (i.e., tiendas) to improve tienda availability and accessibility of FVs, and purchasing and consumption among tienda customers. The primary outcome is customer-reported daily consumption of FVs using the National Cancer Institute FV screener and secondary outcomes including customer-reported purchasing and observed FV availability and accessibility within the tiendas. The El Valor study builds on a previous study conducted in North Carolina that resulted in increased tienda availability of Vs and greater consumption of FVs among tienda customers [21]. An innovation of both studies is the social and structural aspects of the intervention (e.g., social aspects including manager and employee trainings; structural aspects including new equipment), as most small store-based interventions are limited to a food marketing component and displays [18]. This paper describes the El Valor study and presents baseline demographic characteristics of the tiendas, managers, and cohort of tienda customers.

Materials and methods

Overview and study design

El Valor is a cluster randomized controlled trial with 16 pair-matched tiendas randomized to a six-month social and structural intervention or a wait-list control condition. Evaluation activities are designed to determine whether the intervention improves tienda availability and accessibility of FVs, and purchasing and consumption among tienda customers. Regarding tienda availability and accessibility of FVs, source data are collected during face-to-face interviews with tienda managers at three time-points (baseline, and 6- and 12-months post-baseline) and monthly tienda audits. Sales data are obtained when available, and managers are prompted for this information on a monthly basis by El Valor staff. Employees are recruited to participate in the intervention and data collection is limited to intervention involvement. Regarding customer purchasing and consumption, 369 customers (approximately 23 per tienda) were recruited to serve on an evaluation cohort; these are our primary study participants. Customers’ selfreported FV purchasing and consumption data were collected at baseline prior to tienda randomization, and are being collected again at 6- and 12-months post baseline (see Figure 1). The primary outcome is customer-reported daily consumption of FVs using the National Cancer Institute FV screener; secondary outcomes are at the customer (e.g., FV purchasing) and tienda (e.g., availability and accessibility) levels. An extensive process evaluation protocol examines key dimensions of implementation [20,22], such as dose delivered, dose received, and fidelity for all components of the social and structural change intervention. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of San Diego State University.

Figure 1.

Study design

Study foundation and Advisory Committee

El Valor recruitment, intervention, and evaluation protocols were informed by a pilot study in tiendas in North Carolina [20,21], a formative research study with the target population and in tiendas in San Diego [23], previous research in food retail environments [24,25], previous research in workplace interventions [26,27], previous research with Latinos [9,28], and input from an advisory committee comprised of individuals from the national food retail industry and other agencies charged with promoting healthy eating (see acknowledgements). The advisory committee convened during the first year of funding and is meeting four times in-person over the course of the study to provide input on study protocols and activities. During the first two years of the study, the committee’s input was instrumental in developing recruitment protocols and creating intervention components that were relevant to tienda managers and their customers.

Recruitment and eligibility criteria

Tienda enumeration and recruitment

A systematic enumeration of all food stores in San Diego County was conducted using five sources: county food permits, county health department registry, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and a previous observational study conducted in the target area [29]. Duplicate entries were removed resulting in a final list of 5601 outlets eligible for the second phase of screening which involved eliminating those clearly identifiable as other than a food store (e.g., car wash, electronics store, nonretail; n=1488). This new list of 4113 outlets was further reduced by excluding zip codes where US 2000 Census data indicated that the proportion of Hispanic/Latino residents was less than 20% (given our focus on Latinos), as well as San Diego’s South County given competing intervention activities in stores led primarily by the county health department (n=2437). The remaining 1676 outlets were then filtered to exclude known super centers, supermarkets, liquor stores, convenience stores, dollar stores, restaurants, etc. and additional duplicates were removed (n=1110). This left 566 that was further reduced to 339 outlets after excluding those ineligible based on internet or phone verification.

Because 2010 Census data were not available when store enumeration was first conducted, 2000 Census data were used to identify zip codes with sufficient Latino representation. Over time demographic shifts occurred that changed the ethnic composition of various neighborhoods. During the final round of tienda recruitment, given time and resource constraints for traveling to more distant stores, the team identified four additional zip codes in proximity to the study offices that contained census tracts representing at least 20% Latino population. An additional 365 outlets were identified in those zip codes (out of the original 5601). Of those, 268 were dropped because they were identified as an outlet other than a grocery store, then another 54 were excluded because they did not fall within census tracts that contained at least 20% Latino population, leaving an additional 43 outlets to be verified. This brought the total available for verification and potential recruitment to 382.

In-person verification involved a store audit to determine whether the outlet was a food store, and if yes, whether it met study inclusion criteria: carried some fresh produce; had a serviced meat department; was considered small or medium-to-large based on the number of cash registers and store aisles (for matching purposes); and catered to a Latino clientele (e.g., had Spanish language signage; some or all employees observed speaking Spanish; some products from Mexico and other Latin-American countries including specific cuts of meat in the serviced meat department, specific dishes in the serviced prepared food department if available). No criteria were used for number of employees given the wide variation observed in previous studies with similar stores [21,24].

Of this 382 outlets, 273 (71%) were not eligible for various reasons from being a convenience store to no longer in business. Six (1.5%) additional duplicates were found and during ground truthing, 26 new stores were found and added, leaving 129 in the recruitment pool. From among these, 84 tiendas were approached for participation. To minimize the potential for cross-contamination, the 84 tiendas were sorted geographically; once one tienda was recruited, possible pair-matched tiendas were identified that were located at least one mile away from the recruited tienda.

Initial tienda recruitment strategies involved mailing an introductory letter followed by an in-store visit or a phone call to schedule a meeting. However, after several attempts, it was determined that many tienda managers did not recall receiving the letter. Thus, the approach was modified to include a drop-in visit with a fact sheet and introductory letter in-hand, recruitment on-the-spot, or scheduling a meeting to introduce the study to the tienda manager at a later date. The fact sheet included a pilot-study tienda manager testimonial and a testimonial by the president of a regional trade association for independent retailers along with answers to frequently asked questions. During the recruitment meeting with the tienda manager, the project staff member reviewed study requirements and gave the tienda manager a packet to review. If the tienda manager was interested, the staff member completed an initial eligibility screener which involved confirming that the tienda was eligible. If eligibility was met and the manager agreed, the two parties would review and sign a memorandum of understanding.

Manager and Employee recruitment

Tienda manager eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age; having worked at least 20 hours per week for the participating tienda for a minimum of six months; planning to continue as tienda manager for the next 12 months; having had or having decision-making authority in the tienda; being willing to consider providing sales data to researchers; and not being employed at another participating tienda. If the tienda manager was eligible, the project staff member conducted the baseline assessment with him/her. Recruitment of employees to participate in evaluation activities was dropped due to funding cuts. As such, employee recruitment was limited to intervention involvement and is described under Intervention.

Primary study participants: Tienda customers

To screen for eligibility, customers were approached by trained bilingual (English/Spanish) research assistants as they were entering the tienda. As soon as a customer agreed to be screened, recruitment of other customers stopped until all activities were completed with that individual. If the customer expressed initial interest, the research assistant screened him/her for the following eligibility criteria: at least 18 years of age; identified as Latino/Hispanic; primary food shopper for his/her household; purchased food products at the participating tienda at least once per week; not presently consuming more than four cups of FV per day; not having dietary restrictions limiting FV consumption; fluency in English and/or Spanish and able to read Spanish; not shopping at another participating El Valor tienda once a month or more; having a telephone; planning to remain in San Diego County for the next 12 months; and not participating in another research study. To ensure independent observations, only one individual per household could participate. If the customer was eligible and agreed to participate, the research assistant collected the baseline data immediately or scheduled a future visit to collect these data. If the customer refused at any point during recruitment, the refusal was noted, along with important demographic factors such as gender to characterize those who refused. If the customer was ineligible, he/she was thanked for his/her time and ineligibility criteria were noted along with similar demographic factors as those who refused.

Intervention

As summarized in Table 1, the intervention involves social and structural changes in the tiendas, with activities directed at the tienda environment, and the tienda managers, employees, and customers. Research-supported intervention activities are designed to occur over a six-month period, with tienda-, tienda manager- and employee-directed activities occurring over the first two months and customer-directed activities occurring over the subsequent four months; these latter activities occur in the form of biweekly campaigns using a variety of marketing strategies. The ultimate goal of the El Valor intervention is to improve the availability and accessibility of FV in the tiendas, and promote the purchase and consumption among tienda customers.

Table 1.

Intervention components and associated process evaluation measures

| Planned dose | Process evaluation | |

|---|---|---|

| Structural changes | ||

| Tienda-directed | $2000/tienda, three options: Raw produce displays Prepared produce displays Produce hardware Serviced meat dept. – minimum of two changes Serviced prepared foods dept. – minimum of one change |

Mean (SD) dollars spent on tienda % (n) of tiendas that selected each option and what was implemented % (n) of time each option implemented % (n) of each option implemented |

| Social changes | ||

| Employee-directed | 25% of employees receive four-part training (four hours total), a minimum of 1 from each department: Butcher Cashier Stocker Prepared foods, if applicable All others 10-min training |

Percent of employees fully trained and mean hours of training per employee % (n) employees received 10-min training |

| Worksite Posters | Four | Median (range) poster delivered |

| Newsletters | Nine | Median (range) of employees the newsletters were delivered to |

| Customer-directed | ||

| Initial food marketing POP installation and rotation | 60 shelf danglers (rotated with campaign) Four to eight aisle violators (based on tienda size) One poster One banner One produce fact sheet 450 blank EV logo signs (50 per campaign) |

% (n) of POP installed and retained at each weekly visit |

| Biweekly food demonstrations and campaign | Food demonstration announcement flyers 9 unique recipe cards (200 per campaign) 9 unique recipe posters (one per campaign) 225 reusable grocery bags (25 per campaign) 900 magnet calendars (100 per campaign) |

# of flyers distributed # of customers visiting food demo # of taste-test samples given out # of recipe cards distributed # of grocery bags distributed Minutes of food demo |

Tienda and Tienda Manager-directed

The tienda- and tienda manager-directed interventions involve working with the tienda manager to implement social and structural changes in the tiendas. Social changes are targeted through employee trainings and a food marketing point-of-purchase (POP) campaign. To implement structural changes, tienda managers receive $2000 to purchase equipment to help them promote the sale of fresh FVs. They are encouraged to select from three options: (1) raw produce displays (e.g., bins and racks); (2) prepared produce displays (e.g., cold food bars); and/or (3) hardware to improve current produce displays (e.g., misters). In addition, the tienda managers are encouraged to select at least two of three proposed changes to make in their butcher departments: (1) introduce a new meat-vegetable option (e.g., fajitas), (2) introduce study-created POP materials promoting meat and FV pairings, and/or (3) cross merchandize fresh FV in the butcher department. For those tiendas that have a mailed circular, another option is provided to include promotions of fresh meat and FV pairings in the circular. Tiendas with a serviced prepared food department are encouraged to include additional FVs in their menu offerings through implementing one of three proposed changes: (1) offering the El Valor biweekly customer-directed campaign recipe (El Valor recipe) on their prepared food menu the day of the food demonstration; (2) offering one of the El Valor recipes on an ongoing basis; and/or (3) modifying existing menu items to incorporate FVs used in the El Valor recipes. In this way, El Valor targets both the availability and accessibility of FVs in multiple departments and in multiple forms. Decisions on what infrastructure to purchase and what changes to implement in the serviced meat and prepared foods departments are decided collaboratively between the tienda manager and intervention staff member to maximize the sales of fresh FVs and reduce spoilage. These decisions are made over the course of three meetings with the tienda manager, along with decisions about who to train and logistics of the food marketing POP campaign.

Employee-directed

The employee-directed component involves four trainings delivered to at least 25% of tienda employees, a 10-minute introductory training for all other employees, materials to support the trainings (e.g., four worksite posters) and nine employee newsletters delivered in conjunction with the biweekly customer-directed campaigns. An intervention staff member using a study-produced DVD and accompanying materials delivered the four-part training. Training topics include: customer service, product knowledge (focused on FVs), merchandising fresh produce, and how to implement an integrated campaign. Trainings are intended to be delivered optimally in a small group over the course of four 1-hour sessions; however, they can be delivered one-on-one. Trainings include opportunities for role playing and skill practice, with a notable feature of the videos showing ‘good’ and ‘bad’ behaviors (e.g., good and bad customer service) and consequences of these behaviors consistent with behavioral modification principles [30]. At the end of each training session, tienda employees are given a take home ‘skill builder’ assignment to practice what they learned. The intervention staff member posts the related worksite poster which summarizes the key points of the training. During the customer-directed intervention described below, all employees receive a biweekly newsletter at the beginning of each new campaign that describes the upcoming food demonstration, including what FVs are being promoted.

Customer-directed

The 4-month customer-directed intervention, initiated at the beginning of month 3, involves a food marketing POP campaign, including nine biweekly food demonstrations. The POP materials include shelf-danglers (see Figure 2a), aisle violators (see Figure 2b), posters, a banner, a produce fact sheet, and blank signs the tienda personnel can use to promote or price produce. Some of the POP materials are static, remaining in place for the entire four-month period. Every two weeks, five to seven days prior to the food demonstration, certain POP materials (e.g., danglers, posters) are refreshed to highlight the recipe and produce item of that two-week period. Food demonstration announcement flyers are distributed to customers. The recipe is prepared for the four-hour food demonstration to allow for taste-testing. During each demo, recipe cards are offered to customers so they can prepare the recipe themselves, and 25 reusable grocery bags carrying the SABOR and Plato Total messages (details provided below) are distributed to customers. After each food demonstration, remaining recipe cards are made available in the tienda until the new campaign begins, and 100 refrigerator magnet calendars bearing the project tagline are distributed to customers by tienda employees. In addition to replenishing POP materials and updating them to reflect the new campaign each two weeks, the intervention staff member also monitors the structural and butcher changes such as introducing meat-vegetable pairings, and if applicable, changes in the serviced prepared food department. To maximize implementation fidelity, the intervention staff member addresses concerns with the tienda manager either immediately or soon thereafter.

Figure 2.

a. Shelf dangler

b. Aisle violator

In preparation for the food demonstrations, the intervention staff member encourages the tienda manager to ensure that all of the items promoted for the week are available for purchase in the tienda. Tienda managers are also asked to identify a tienda employee to assist with the food demonstrations to maximize the possibilities for sustaining this intervention component upon study completion. Consistent with the pilot study [20], the food marketing POP campaign was informed by theory and behavior change strategies [31,32]. Two core messages of our campaign are SABOR and Plato Total (see Figure 3). Although the former loosely translates to ‘taste’, SABOR is an acronym referring to five behavioral strategies used to promote healthy eating [33,34]: substitute, add, balance, opt for variety, and reduce. The goal is to elicit behavior change among customers through the use of POP materials. For example, as depicted in Figure 2a, each shelf dangler incorporates one of the five behavioral strategies in its message (i.e., English translation: Bored with bland rice? Opt for broccoli, carrots, red bell peppers and peas to make it more colorful). Our “Plato Total” (Total Plate) was based on a previous study [7,35] in which the concept was used to promote healthy eating in a family-based intervention; however, it is also similar to the United States Department of Agriculture’s “Choose My Plate” dietary guidelines [http://www.choosemyplate.gov/][36]. The Plato Total encourages customers to make half their plates FVs, a quarter whole grains, and a quarter lean proteins. The Plato Total image and messages are also incorporated into many of the POP materials. The two are combined into the following tagline: Póngale SABOR a su Plato Total (Put taste into your total plate).

Figure 3.

Image of Plato Total marketing

Wait-list control condition

Tiendas randomly assigned to the wait-list control condition are offered a three-part employee training following completion of their 12-month assessments, including assessments with tienda customers. The training includes the same components as the intervention training, excluding the fourth training because it is tailored specifically to the El Valor food marketing POP campaign that control tiendas do not receive.

Measurement

Impact and outcome data collection is designed to determine whether the intervention successfully improves availability and accessibility of FVs, and purchasing and consumption among tienda customers in intervention versus wait-list controls. Our primary outcome is customer-reported daily consumption of FVs; secondary outcomes include customer-reported purchasing of FVs and tienda availability and accessibility of FVs. Except where specified, data collection is occurring at three time-points: baseline, 6- months post-baseline and 12-months post-baseline.

Manager interviews

Manager interviews capture information about the tiendas and about the tienda managers themselves, including their eating habits consistent with customer data collection described below. Tienda information includes tienda size and staffing among other variables. At 6- and 12-months, the interview also includes process evaluation questions about intervention implementation.

Tienda audits

Tienda audits are occurring every four weeks in addition to the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month assessments to capture changes in the tiendas, specifically availability and price of fresh produce items, the extent to which fresh produce is available in other departments (e.g., butcher, prepared foods), whether the tienda is engaging in additional promotions of FVs, and whether more floor space is devoted to fresh produce over the course of the study. Availability of canned and frozen produce is also assessed. Research assistants, blinded to treatment condition at baseline, were trained to conduct these unobtrusive audits. At baseline, all audits are conducted with a second observer, and at the 6- and 12-month time-points, a 50% random sample of audits are conducted with a second observer present to assess inter-rater reliability. By the nature of the POP campaign, it was impossible to maintain blinding of research assistants after the customer-directed intervention was implemented.

Tienda sales data

Managers are asked to provide weekly or monthly sales data, including overall sales, produce sales, produce purchase figures, and sales of prepared foods, if applicable. The formats in which these data are received varies by each tienda’s capacity, and include daily register receipts and produce invoices, hard-copy tables and electronic files.

Primary participants: tienda customers

The primary outcome is daily consumption of FVs. This information is obtained using the National Cancer Institute (NCI) All Day FV Screener [37], which consists of 19 items on how frequently the respondent consumed FVs in various forms and how much was consumed during the past month. Food models and measuring cups are used to improve data collection consistent with recommendations [38]. The secondary outcome is self-reported grocery and produce purchasing at that tienda and other food stores. Additional variables include percent energy intake from fat using the NCI Fat Screener [39], behavioral strategies to increase FV intake and reduce fat [33], and the total variety of FVs consumed in the past month. Potential moderators (e.g., eight-item scale measuring the extent to which tienda marketing influences grocery purchasing) and mediators (e.g., tienda characteristics and tienda employee characteristics; barriers to healthy eating) are also being examined.

Planned analyses

Bivariate analyses will be used to describe the characteristics of the sample by intervention and control group. All analyses will be carried out according to the intention-to-treat rule consistent with standard practice in most trials. The primary aim of this study is to assess the impact of the intervention on customer-reported daily consumption of FVs between baseline and immediately post-intervention (approximately 6 months post baseline). The primary dependent variable is a continuous measure that is normally distributed or may be transformed to approximate normality by natural log or the Box-Cox transformation. Thus, normal-based models will be emphasized, with care taken to assess this assumption and, if necessary, apply appropriate transformations. Based on bivariate analyses (independent sample t-test and chi-square test), significant demographic differences between the two conditions will be included in the subsequent multivariate mixed model analysis for covariance adjustment.

For the primary aim of assessing the effectiveness of the intervention on customers’ daily intake of FVs, we will use the two-level (individual level and tienda level) mixed effects models treating the immediate post-intervention FV intake as the dependent variable. The primary predictor, condition assignment, along with baseline FV intake and significant demographic differences between the two conditions will be placed in the fixed effect part of the models. These covariates will be adjusted for their influence on the intervention effect. Finally, the tienda ID will be placed in the random effect part of the model to adjust for the clustering effects. This model will allow us to compare the effect of intervention on FV intake while adjusting for participants’ baseline FV intake. A number of studies have shown that adjusting the baseline outcome (i.e., FV intake) as a covariate has more power and precision than assessing the change over time using the repeated-measure approach [40]. Further, we also expect that the intervention effect on FV intake may differ between men and women [41]. In another model, we will place gender and the gender × condition interaction term in the fixed effect portion of the model to assess the differential response to the intervention by gender. If the interaction term is not significant, we will drop it from the final model. The proposed multilevel models will be fitted using SAS PROC MIXED or PROC GLIMMIX when examining non-normal variables such as a dichotomous outcome.

Sample size estimation

The intervention was powered to detect a positive difference of 0.90 (0.20) servings of FV intake among intervention versus control tienda customers at the 6-month post-baseline measurement time-point. This rate of change was based on our pilot study results [20,21] and considered along with other design elements to determine our tienda and customer sample sizes: an estimated intraclass correlation of 0.11 to account for tienda clustering and a six-month retention rate of 90%. To achieve 80% power, we recruited 16 tiendas and approximately 23 customers per tienda for a total sample size of 369 customers.

Process evaluation

An extensive process evaluation protocol, similar to that used in our pilot study [20], is being implemented including logs completed by the intervention staff member prior to, during, and after each food demonstration; logs completed by the intervention staff member at each POP campaign maintenance visit; attendance logs at employee trainings and training attendee satisfaction surveys; randomly selected independent observations of employee trainings by a process evaluator; and intervention exposure questions asked of the customers and managers at the 6- and 12-month time points. Ultimately our process evaluation will address questions related to dose delivered, dose received, and fidelity at the tienda and customer levels.

Results to date

Recruitment of tiendas and tienda managers occurred in three waves, in part, for staffing reasons. Tiendas were pair-matched at recruitment to ensure equivalency across tienda characteristics randomized to condition (e.g., presence of a prepared food department; number of cash registers and aisles). Thus, once a tienda was recruited, a second tienda from the list was recruited that was similar in size and characteristics to the recruited tienda but sufficiently at a distance from the recruited tienda to minimize cross-contamination. After all baseline assessments were completed within the pair-matched tiendas, and with their respective tienda managers and customers, one tienda was randomly assigned to the intervention condition and the second to the wait-list control condition.

Eighty-four tienda managers were approached for participation; 12% (n=10) refused to participate without hearing about the study and an additional 18% (n=11) refused after hearing about the study (see Figure 1). Three tiendas (4%) were immediately determined ineligible (not Latino or going out of business), and after further screening, 11% (n=7) more were excluded for various reasons, among them not having a majority Latino clientele, changing the format to a 99 cent store, or being the former manager of a participating El Valor tienda. In 17% (n=14) of the tiendas, eligibility was undetermined because recruitment ended before eligibility was finalized. Two tiendas went out of business before being presented the study.

From among the remaining 37 stores screened for eligibility, 51% (n=19) agreed to participate, 14% (n=5) refused, 19% (n=7) were ineligible for similar reasons and 14% (n=5) were eligible but not enrolled because recruitment goals were met prior to an agreement being reached. One tienda went out of business during recruitment. Thus, the recruitment rate based on eligible-agreed/eligible-refused was 79%. After initially agreeing, one tienda refused to continue participate, and one tienda, and by extension its pair, were dropped during customer recruitment given concerns for staff safety. The final tienda sample size is 16.

Among the reasons given for participating, tienda managers noted that they appreciated the opportunity to receive resources and staff training. Others wanted to help members of their community. Among reasons given for refusing to participate, tienda managers reported that they were too busy or not interested, their tiendas were undergoing changes during the upcoming months or they felt the business was too unstable to be involved. However, other managers reported that because customers were not interested in health, it would be a waste of time for their tienda and their employees to participate. Depicted in Tables 2 and 3 are customer, manager, and tienda characteristics from baseline. Nearly one-third of the customers were male and 36% of the customers had a high school education. Similar percentages were WIC recipients and/or SNAP recipients. FV consumption averaged three cups daily. Few differences were observed between intervention versus control condition customers. Intervention condition customers were more likely to live in poverty (78%) compared with control condition customers (65%; p<0.005) and they were less likely to be homeowners (14% versus 25% respectively; p<0.01). Intervention condition customers were also more likely to be traditional or Spanish language dominant compared with control condition customers (71% versus 59%, respectively; p<0.05). Tienda managers were mostly male (88%), employed full-time (94%), and had a high school education or greater (88%). The intervention and control tiendas were similar on a number of dimensions including number of aisles, cash registers, employees, and departments. On average, between seven to 25% of weekly sales are attributed to sales of fresh FVs, an aspect of the tiendas that we are examining further.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the customers and tienda managers/owners

| Customers (N=369) | Managers/Owners (N=16) | |

|---|---|---|

| % (n) or Mean (SD) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 42 (12) | 40 (14) |

| Male | 30% (110) | 88% (14) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 100% (369) | 47% (7)a |

| High school educated or greater | 36% (132) | 88% (14) |

| Employed full-time | 60% (128) | 94% (15) |

| Financial assistance | ||

| WIC recipient | 33% (120) | NRb |

| SNAP recipient | 33% (120)c | NRb |

| Primary aim | ||

| Daily fruit and vegetable intake (cups) | 3 (2) | NRb |

Missing ethnicity information for managers: (n=1).

NR=not reported

Missing SNAP recipient information: (n=1).

Table 3.

Tienda and manager employment characteristics based on observed and manager-reported data

| Total (N=16) | Intervention (n=8) | Control (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) or Mean (SD) or Median (range) | |||

| Observed data during a baseline audit | |||

| Aisles | 4 (2–9) | 4 (3–9) | 4 (2–7) |

| Cash registers | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) |

| Serviced bakery or tortilleria | 25% (4) | 25% (2) | 25% (2) |

| Serviced prepared foods dept. | 38% (6) | 38% (3) | 38% (3) |

| Have tienda flyer | 56% (9) | 63% (5) | 50% (4) |

| Manager-report on tienda | |||

| Years tienda in operation | 20 (2–70) | 14 (2–50) | 20 (18–70) |

| Full time employees | 6 (2–40) | 5 (3–40) | 8 (2–30) |

| Part-time employees | 3 (0–20) | 3 (0–8) | 4 (2–20) |

| Sales floor in sq. footagea | 3,500 (1,080–20,000) |

5,000 (1,800–20,000) |

3,500 (1,080–12,000) |

| Number of SKUsb | 5,000 (500–120,000) |

4,000 (500–120,000) |

7,000 (575–100,000) |

| Produce distributors | 6 (2–15) | 6 (3–8) | 6 (2–15) |

| Certified WIC vendor | 69% (11) | 63% (5) | 75% (6) |

| Weekly sales in $c | 28,500 (8,000–100,000) |

22,000 (17,500–100,000) |

37,500 (8,000–75,000) |

| Weekly produce sales in $d | 6,500 (1,500–19,000) |

4,000 (1,500–19.000) |

10,000 (2,600–10,500) |

| Customers on typical weekday | 550 (150–1450) |

600 (250–1450) |

450 (150–1250) |

| Manager-report on self | |||

| Tienda owner | 50% (8) | 63% (5) | 38% (3) |

| # of other food stores owns | 1 (1–13) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–13) |

| Years managed this tienda | 5 (1–24) | 4 (1–24) | 6 (1–20) |

| Hours works in typical day | 8 (4–16) | 8 (4–16) | 8 (7–12) |

Sales floor square footage missing: intervention (n=1) and control (n=1).

SKUs missing: control (n=1)

Weekly sales missing: control (n=4)

Weekly produce sales missing: intervention (n=1) and control (n=5)

Discussion

This paper describes a cluster randomized controlled trial to test an innovative social and structural intervention designed to promote the availability and accessibility of FVs in small-to-medium-sized Latino food stores (tiendas), as well as purchasing and consumption among tienda customers. The primary outcome is customer-reported daily consumption of FVs. The six-month intervention involves changes in the manner in which FVs are marketed to customers, including changes in the display, marketing, and promotion of FVs by employees and managers. In addition to evaluating changes among a cohort of tienda customers over a 12-month period, changes are being examined among tienda managers and within the tiendas themselves. An extensive process evaluation protocol examines dose delivered, dose received and fidelity. To our knowledge and based on several reviews [16,19,42], El Valor is among one of two studies [43] to test a social and structural intervention to promote FVs.

Tiendas are an innovative setting in which to conduct health promotion research involving US Latinos. Among Latinos, particularly among traditional Latinos, tiendas are frequented more often than supermarkets [44]; Latinos also have greater access to these types of food stores in their communities [45], and recent evidence suggests that they could serve as an ideal venue to promote FVs [24]. They do not introduce the same challenges in the promotion of fresh FVs as convenience stores given no existing infrastructure in the latter [42]. This is the second of two studies conducted in this setting, the former taking place in a new immigrant-receiving community in North Carolina, an area of the US that offered employment in poultry processing plants and other types of factories [46]. The former study helped us learn that tiendas in new immigrant receiving communities are gateways of entry into the US [20,21]. Tiendas serve as a hub where immigrants can obtain information about community resources and sources of employment; they are also places where immigrants can send home remittances and stay connected to their countries of origin, for example, through foods purchased. Similarly, in established immigrant receiving communities, they are an access point for maintaining culturally-derived food habits through the types of foods and beverages available for purchase. In addition, customers will find an employee or manager who speaks Spanish. Importantly, tiendas are visited more frequently than supermarkets or big box stores, in part because the types of shopping trips that occur involve ‘fill-in’ or ‘quick-trip for a meal’ activities. Among Latinos living on the US-Mexico border, approximately 33% of a family’s weekly food basket was purchased from tiendas [44].

Limitations

A few limitations of the study are acknowledged. Although funding was requested for the collection of biomarkers, this evaluation protocol was dropped after a 25% reduction in funding from study inception. This limits our ability to determine, with more precision than is afforded with a food screener, the clinical meaningfulness of study findings. Similarly, employee data collection was reduced after the first wave of tiendas given continued funding reductions in subsequent years. This limits our ability to determine whether any possible changes observed in the customers are, in part, due to changes observed in the employees. Finally, challenges remain in our ability to collect sales data; at study end we will have it for a limited number of tiendas and periods of time; the validity of the data also will be examined. Collection of sales data is a common problem and has been identified by previous researchers conducting intervention work in stores, even supermarkets [19]. Smaller stores are less likely to have point-of-sale systems that allow easy access to sales data by product category. Independent store managers and owners are also wary of providing sales data to outsiders. Thus, this examination will be limited but it will provide much needed evidence on the impact of the intervention on store sales.

Conclusions

Dietary intake of FVs is not meeting USDA guidelines and this is more pronounced among Latino males versus females [2], and more generally, among racial/ethnically diverse individuals compared with whites [1]. Evidence-based interventions are needed that affect change in other settings in which diet-related decisions are made, such as during food purchasing in food stores [19], a precursor to sustaining changes in dietary intake. The El Valor study has the potential to inform industry and public health practice on effective methods for modifying their food stores to promote purchasing of FVs among their customers.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award Number R01CA140326. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the El Valor Advisory Board for their invaluable service to the project: Mark Arabo, Neighborhood Market Association; Jan DeLyser, California Avocado Commission; William Drake, Cornell University Food Industry Management Program; Nestor Martinez, California Department of Public Health; Sylvia Melendez-Klinger, Hispanic Food Communication, Inc.; Victor Paz, Network for a Healthy California; Cathy Polley, Food Marketing Institute Foundation; Dick Spezzano, Spezzano Consulting Services, Inc.; and Christina Tamayo, Otay Farms Market and Restaurant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe X. Ayala, Email: ayala@mail.sdsu.edu.

Barbara Baquero, Email: barbara-baquero@uiowa.edu.

Julie L. Pickrel, Email: jpickrel@mail.sdsu.edu.

Joni Mayer, Email: jmayer@mail.sdsu.edu.

George Belch, Email: belch@mail.sdsu.edu.

Cheryl L. Rock, Email: crock@ucsd.edu.

Laura Linnan, Email: linnan@email.unc.edu.

Joel Gittelsohn, Email: jgittel1@jhu.edu.

Jennifer Sanchez-Flack, Email: jesanchez@mail.sdsu.edu.

John P. Elder, Email: jelder@mail.sdsu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults --- United States, 2000–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1125–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Kimmons JE, Seymour JD, Serdula MK. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among U.S. men and women, 1994–2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1330–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pomerleau J, Lock K, Knai C, McKee M. Interventions designed to increase adult fruit and vegetable intake can be effective: a systematic review of the literature. J Nutr. 2005;135:2486–2495. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson CA, Ravia J. A systematic review of behavioral interventions to promote intake of fruit and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR, Slymen D, Lopez-Madurga ET, Engelberg M, et al. Interpersonal and print nutrition communication for a Spanish-dominant Latino population: Secretos de la Buena Vida. Health Psychol. 2005;24:49–57. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayala GX, Ibarra L, Horton L, Arredondo EM, Slymen DJ, Engelberg M, et al. Evidence supporting a promotora-delivered entertainment education intervention for improving mothers’ dietary intake: the Entre Familia: Reflejos de Salud study. J Health Commun. 2014;6:1–12. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.917747. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, Talavera GA. Health communication in the Latino community: issues and approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:227–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J Community Health. 2008;33:395–406. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DJ, Pelletier JE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lust K, Laska MN. Perceived social-ecological factors associated with fruit and vegetable purchasing, preparation, and consumption among young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:1366–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.06.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood C, Martinez-Donate A, Meinen A. Promoting healthy food consumption: a review of state-level policies to improve access to fruits and vegetables. WMJ. 2012;111:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Khan T, Wada R, Chaloupka FJ. Assessing the potential effectiveness of food and beverage taxes and subsidies for improving public health: a systematic review of prices, demand and body weight outcomes. Obes Rev. 2013;14:110–128. doi: 10.1111/obr.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glanz K, Yaroch AL. Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: Policy, pricing, and environmental change. Prev Med (Baltim) 2004;39:S75–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zenk SN, Powell LM, Odoms-Young AM, Krauss R, Fitzgibbon ML, Block D, et al. Impact of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package policy on fruit and vegetable prices. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Karpyn A, Klingler K, Ayala GX. Lessons learned from small store programs to increase healthy food access. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38:307–315. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayala GX, Elder JP, Campbell NR, Slymen DJ, Roy N, Engelberg M, et al. Correlates of body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio among Mexican women in the United States: implications for intervention development. Women’s Heal Issues. 2004;14:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.07.003. doi:S1049-3867(04)00070-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.whi.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escaron AL, Meinen AM, Nitzke SA, Martinez-Donate AP. Supermarket and grocery store-based interventions to promote healthful food choices and eating practices: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E50. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baquero B, Linnan L, Laraia BA, Ayala GX. Process evaluation of a food marketing and environmental change intervention in tiendas that serve Latino immigrants in North Carolina. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15:839–848. doi: 10.1177/1524839913520546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala GX, Baquero B, Laraia BA, Ji M, Linnan L. Efficacy of a store-based environmental change intervention compared with a delayed treatment control condition on store customers’ intake of fruits and vegetables. Public Heal Nutr. 2013;16:1953–1960. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steckler A, Linnan L. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Flack JC, Baquero B, Linnan LA, Gittelsohn J, Pickrel JL, Ayala GX. What influences Latino grocery shopping behavior? Perspectives on the small food store environment from managers and employees in San Diego, CA. Ecol Food Nutr. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2015.1112282. (Under review). n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emond JA, Madanat HN, Ayala GX. Do Latino and non-Latino grocery stores differ in the availability and affordability of healthy food items in a low-income, metropolitan region? Public Heal Nutr. 2012;15:360–369. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duerksen SC, Campbell N, Arredondo EM, Ayala GX, Baquero B, Elder JP. Aventuras para Niños: Obesity prevention in the homes, schools, and neighborhoods of Mexican American children. In: Brettschneider W-D, Naul R, editors. Obes Eur Young people’s Phys Act sedentary lifestyles. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang Publishing; 2007. pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnan LA, Birken BE. Small businesses, worksite wellness, and public health: a time for action. N C Med J. 2006;67:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JR, Hannon PA, Beresford SAA, Linnan LA, McLellan DL. Health promotion in smaller workplaces in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:327–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder JP, Ayala GX, McKenzie T, Litrownik AJ, Gallo L, Arredondo EM, et al. A three decade evolution to transdisciplinary research: community health research in California-Mexico border communities. Prog Community Heal Partnersh. 2014;8:397–404. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Couch SC, Zhou C, Colburn T, et al. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: the Neighborhood Impact on Kids study. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:e57–e64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanfer F, Goldstein AP. Helping people change. Elmsford, New York: Pergamon Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2014:1–22. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kristal AR, Shattuck AL, Henry HJ. Patterns of dietary behavior associated with selecting diets low in fat: reliability and validity of a behavioral approach to dietary assessment. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990;90:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Arredondo EM, Campbell NR. Evaluating psychosocial and behavioral mechanisms of change in a tailored communication intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:366–380. doi: 10.1177/1090198107308373. doi:1090198107308373 [pii] 10.1177/1090198107308373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton LA, Parada H, Slymen DJ, Arredondo E, Ibarra L, Ayala GX. Targeting children’s dietary behaviors in a family intervention:“Entre familia: reflejos de salud”. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(Suppl 3):397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States Department of Agriculture. MyPlate 2011. http://www.choosemyplate.gov.

- 37.Greene GW, Resnicow K, Thompson FE, Peterson KE, Hurley TG, Hebert JR, et al. Correspondence of the NCI Fruit and Vegetable Screener to repeat 24-H recalls and serum carotenoids in behavioral intervention trials. J Nutr. 2008;138:200S–204S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.1.200S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayala GX. An experimental evaluation of a group-versus computer-based intervention to improve food portion size estimation skills. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:133–145. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, Kahle LL, Schatzkin A, Kipnis V. Performance of a short tool to assess dietary intakes of fruits and vegetables, percentage energy from fat and fibre. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:1097–1105. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Breukelen GJP. ANCOVA versus change from baseline: more power in randomized studies, more bias in nonrandomized studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.007. [corrected]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Produce for Better Health Foundation. State of the Plate, 2015 Study on America’s Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. 2015 http://www.pbhfoundation.org. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jetter KM, Cassady DL. Increasing fresh fruit and vegetable availability in a low-income neighborhood convenience store: a pilot study. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:694–702. doi: 10.1177/1524839908330808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ball K, McNaughton SA, Mhurchu CN, Andrianopoulos N, Inglis V, McNeilly B, et al. Supermarket Healthy Eating for Life (SHELf): protocol of a randomised controlled trial promoting healthy food and beverage consumption through price reduction and skill-building strategies. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayala GX, Mueller K, Lopez-Madurga E, Campbell NR, Elder JP. Restaurant and food shopping selections among Latino women in Southern California. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.023. doi:S0002822304016980 [pii] 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lisabeth LD, Sanchez BN, Escobar J, Hughes R, Meurer WJ, Zuniga B, et al. The food environment in an urban Mexican American community. Health Place. 2010;16:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, Phipps S. Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. J Interprof Care. 2004;18:403–415. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]