Abstract

Background

The Families Improving Together (FIT) randomized controlled trial tests the efficacy of integrating cultural tailoring, positive parenting, and motivational strategies into a comprehensive curriculum for weight loss in African American adolescents. The overall goal of the FIT trial is to test the effects of an integrated intervention curriculum and the added effects of a tailored web-based intervention on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents.

Design and setting

The FIT trial is a randomized group cohort design the will involve 520 African American families with an overweight adolescent between the ages of 11–16 years. The trial tests the efficacy of an 8-week face-to-face group randomized program comparing M+FWL (Motivational Family Weight Loss) to a comprehensive health education program (CHE) and re-randomizes participants to either an 8-week on-line tailored intervention or control on-line program resulting in a 2 (M+FWL vs. CHE group) × 2 (on-line intervention vs. control on-line program) factorial design to test the effects of the intervention on reducing z-BMI at post-treatment and at 6-month follow-up.

Intervention

The interventions for this trial are based on a theoretical framework that is novel and integrates elements from cultural tailoring, Family Systems Theory, Self-Determination Theory and Social Cognitive Theory. The intervention targets positive parenting skills (parenting style, monitoring, communication); cultural values; teaching parents to increase youth motivation by encouraging youth to have input and choice (autonomy-support); and provides a framework for building skills and self-efficacy through developing weight loss action plans that target goal setting, monitoring, and positive feedback.

1. Introduction to the Rationale for the FIT Trial

The rate of adolescent obesity has tripled in the past three decades1 with 40% of African American adolescents now overweight or obese.2 Adolescent obesity has been associated with increased risks of elevated blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory abnormalities.3–5 Ethnic minorities are also more likely to have medical complications related to being overweight or obese6 and costs associated with these complications are estimated at $78 billion annually7 with estimated indirect costs of over $65 billion in the United States.8 Despite efforts to reduce this high rate of obesity in ethnic minority adolescents, previous weight-loss studies in ethnic minority adolescents have largely failed to produce significant results.9–12 Thus, the need for effective interventions to address disparities in obesity and associated chronic illnesses remains a national priority for ethnic minority youth.

This ineffectiveness of previous weight-loss programs may, in part, be because the content of many weight loss programs has rarely integrated cultural, social and intrapersonal factors to increase motivation for sustained weight loss effects specific to ethnic minority adolescents.10,11 Past research has shown that ethnic minorities attend fewer intervention sessions, have higher attrition rates, and lose less weight as compared to Caucasians.13–15 The proposed randomized controlled trial will expand on past research by testing the efficacy of integrating cultural tailoring, parenting skills, and motivational strategies into a comprehensive curriculum for weight loss in African American adolescents and their parents. Specifically, the proposed study will test the effects of an integrated intervention curriculum and the added effects of a tailored web-based intervention on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents and their parents.

Previous reviews on childhood obesity treatment approaches have primarily focused on randomized controlled trials that do not specifically target ethnic minority populations.16–19 For example, of the 22 randomized controlled trials reviewed by Whitlock et al.,19 only two focused exclusively on ethnic minority youth. Identifying effective intervention strategies is important, given that a recent meta-analysis18 showed that the majority of the weight loss programs among all youth (regardless of ethnicity) did not produce statistically reliable effects. A meta-analytic review by our group11 also concluded that family-based interventions that target authoritative parenting styles (high levels of support, moderate levels of parental control) and positive parenting strategies (monitoring, positive family interactions) had the greatest success in producing weight loss outcomes in youth. Although previous studies have integrated parenting practices into their weight loss interventions,11,20,21 few have targeted positive parenting skills, motivational strategies, and cultural issues to promote weight loss in African American adolescents. A preliminary study by our group found that this integrated theoretical approach that incorporates culturally tailored messages and that integrates a motivational and parenting approach was effective at decreasing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents.22

Programs that incorporate behavioral skills and parental involvement have been successful in middle to upper class children and have demonstrated long-term success.23–25 However, few programs have been shown to be effective in producing similar weight losses in underserved and ethnic minority adolescents. In fact, a recent review by Barr-Anderson26 of 27 family-based obesity treatment and prevention programs for African American youth did not find any specific family-based strategies to recommend as best practice for this population. Thus, more work is needed to understand how best to include the family, a best practice approach for weight management in youth, in programs for African American youth. Past programs may have failed to incorporate appropriate curriculums for engaging African American youth and their families in long-term behavior change. In the current study, we hypothesize that a shorter group-based intervention will be more effective, given the results of our previous studies,22 and that this approach will reduce the likelihood of participant fatigue that has been problematic in past studies. Many past programs have also not integrated motivational strategies or parenting skills that focus on targeting authoritative parenting styles which incorporate shared-decision making, setting appropriate boundaries, providing moderate levels of monitoring, and using effective conflict resolution within the context of a supportive family environment.10,11 Previous studies indicate that autonomy around health behaviors may be co-constructed, or based on a set of interactions in which adolescents and parents negotiate with one another.27 However, in a recent qualitative study by our group, African American adolescents28 reported wanting increased autonomy from families, but were unable to describe how they might negotiate these desires. Thus, the present study will specifically target improving parenting and communication skills between African American parents and their adolescents.

Previous weight loss studies have been relatively long in duration, lasting typically 12 to 25 weeks. However, a previous pilot study demonstrated positive improvements in body mass index (BMI) and dietary intake during a brief 6-week intervention.22 A recent review also showed larger effect sizes for shorter weight loss interventions in comparison with longer programs.21 Considering the multiple demands on time in underserved families with children, developing shorter programs that require less time is essential. Many weight loss programs also show high levels of attrition limiting their effectiveness in ethnic minority families who are unable to sustain attendance.13–15

The proposed study is designed to include 8 group face-to-face sessions plus 8 on-line sessions based on previous large-scale efficacy trials. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)29,30 and Look AHEAD trials31–33 which both include 16 (or more) sessions have been successfully used in dissemination studies.34,35 The DPP trial involved 16 intensive lifestyle sessions and was successful in reducing risk for diabetes and cumulative incidence of diabetes over 10 years.29,30 Our intervention is consistent with these trials that have been successfully disseminated and the addition of the tailored on-line intervention expands on the DPP and Look AHEAD trials and should be relatively easy to disseminate. Given that underserved ethnic minorities often live in hard to reach areas utilizing an on-line intervention may be more easily disseminated in future interventions if shown effective.

To reduce participant drop out and fatigue, the present trial tests a weight loss program in African American youth and their families that specifically addresses cultural issues and provides modalities to peak interest and on-going engagement in weight loss efforts. Prior research has found that cultural factors may serve as barriers to weight loss.36 For example, Blixen and colleagues36 found that African American women reported that factors related to culture and ethnicity, food cravings, and family strongly influenced eating habits and made successful weight loss difficult. Despite evidence suggesting that cultural factors influence weight loss, relatively little attention has been devoted to understanding approaches that may be culturally appropriate for impacting long-term behavior change among ethnically-diverse children and adolescents.10,37 The Hip-Hop to Health Jr. program incorporated cultural strategies, including targeting culturally relevant foods, music and dance, in the context of a teacher delivered, obesity prevention program for African American preschoolers.38 The study demonstrated significant increases in physical activity and decreases in screen time among preschoolers participating in the intervention program, though no changes in BMI were found. Another study, the BOUNCE intervention, tested the effectiveness of a culturally tailored health promotion program on increasing aerobic endurance and reducing weight loss in Hispanic and African American adolescent girls.39 The program incorporated both surface-level (e.g., culturally relevant foods and dance) and deep structure (e.g., use of peer support, important of respect and maternal role modeling) cultural tailoring. Results demonstrated significant reductions in percent body fat and time to run 1-mile. Together, these findings suggest that the inclusion of culturally relevant strategies may lead to improved health outcomes for minority youth, though more research is needed which applies cultural strategies to adolescent weight loss. Thus, we propose a novel approach in the current efficacy trial that integrates cultural tailoring, such as the inclusion of culturally relevant curriculum,40 into program materials and that includes adding an on-line intervention to compliment the brief face-to-face motivation plus family weight loss (M+FWL) intervention to extend the dose of the intervention to promote sustained effects of weight loss at a 6-month follow up.

Past on-line or web-based programs have also been used successfully to promote weight loss and improvements in diet and physical activity among adults41–43 and adolescents.44–49 A recent review found evidence that technology-based interventions, including web-based weight loss programs, may be efficacious in promoting weight loss and increasing physical activity in adolescents.47 However, none of the studies reviewed integrated intervention components for targeting positive parenting strategies or cultural issues related to weight loss. Other research has demonstrated that web-based interventions may be relatively easy to disseminate and more likely to lead to improvements in health behaviors related to diet in ethnic minority50–53 and low income49 adolescents. Schwinn and colleagues49 tested a brief web-based, family-involvement health promotion program designed for adolescent girls living in public housing and their mothers. The program focused on developing positive mother-daughter relationships and targeted family communication and coping skills. The program demonstrated significant improvements in fruit intake among the girls and improved vegetable intake and physical activity in the mothers. This research provides important evidence that web-based programs may lead to improved health behaviors among adolescents, including underserved adolescents. However, to date, few previous randomized controlled trials have been conducted to test the efficacy of on-line web-based interventions on reducing obesity in overweight African American adolescent and their parents.54 A preliminary study by our group that evaluated a similar on-line web-based program was rated as well-liked and easy to use by African American parents.55 Thus the proposed study design is unique in that will allow us to test both the effects of the group motivational plus family weight loss (M+FWL) curriculum (compared to a comprehensive health education program; CHE) and the added dose effects of the tailored on-line intervention component on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents and their parents. After the group session, participants will be re-randomized to either an 8-week on-line intervention or control on-line program resulting in a 2 (M+FWL vs. CHE group) × 2 (intervention vs. control on-line program) factorial design. The specific aims of this study are:

To determine the efficacy of a brief 8-week face-to-face group M+FWL program versus CHE program on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents at 8 weeks (i.e., post-group intervention).

To determine the efficacy of an 8-week online intervention vs. control on-line program that extends the dose of the group intervention on reducing z-BMI at 16 weeks (i.e., post-on-line intervention) and at a 6-month post-intervention follow-up, including the average effect as well as the added dose effect (i.e., in combination with the M+FWL group-based intervention), in overweight African American adolescents. Similar analyses will also be conducted to determine the effects of the FIT trial on parent z-BMI outcomes.

2. Study Design and Recruitment Approach

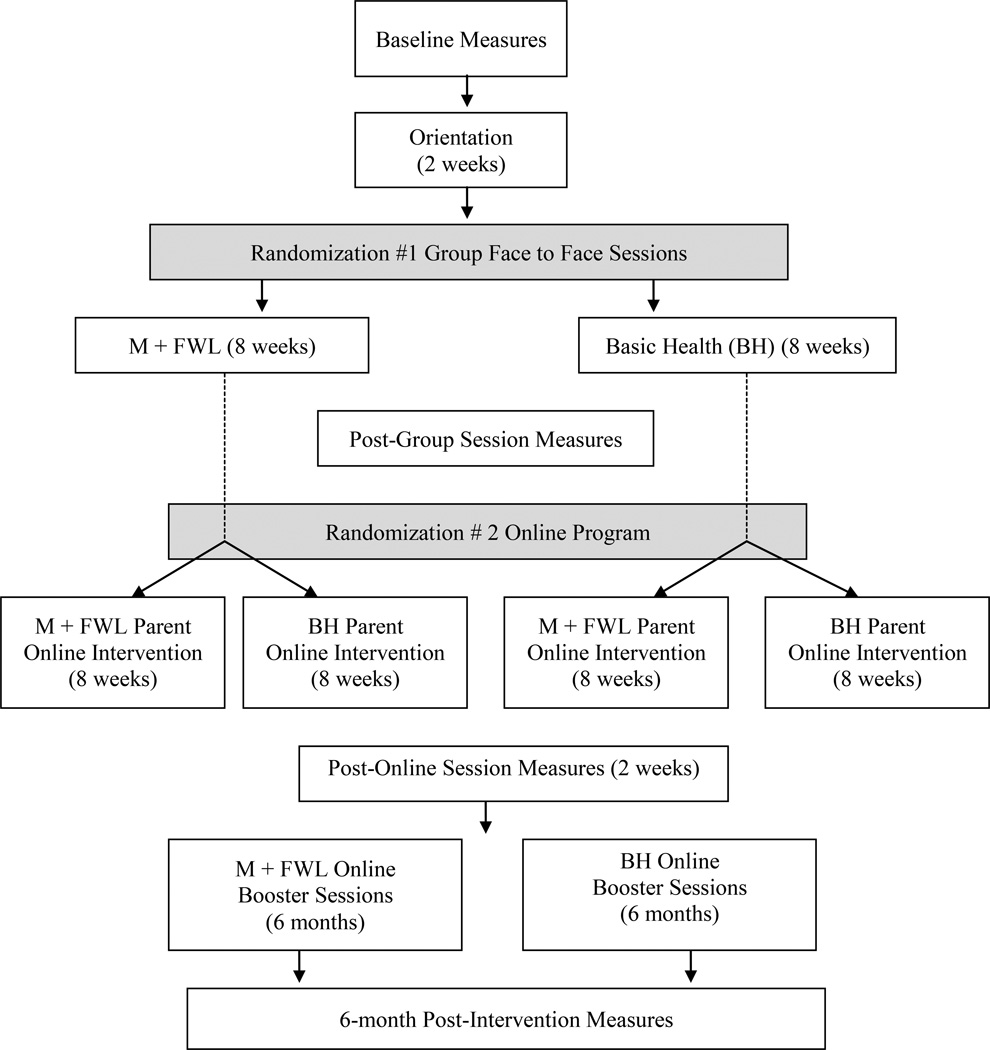

The FIT trial is a randomized group cohort design (see Figure 1). The trial will be implemented over 5 years (2012–2017) and uses a multiple cohort design that includes 52 groups of 5–10 families per group across 13 cohorts (two intervention and two comparison group per cohort). Group composition was created such that there were at least two boys in each group. Families are randomly assigned to one of two possible evenings (Tuesdays or Thursdays) using a computer generated randomized algorithm. After the 2-week run in, evenings were then randomized to a condition (M+FWL or CHE) using another computer generated randomized algorithm.

Figure 1.

Study Design

The first phase of the proposed trial tests the efficacy of an 8-week face-to-face group randomized program comparing M+FWL to CHE on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents and their parents. In phase two of the trial, participants are re-randomized to either an 8-week on-line tailored intervention or control on-line program resulting in a 2 (M+FWL vs. CHE) × 2 (on-line intervention vs. control on-line program) factorial design. This design tests both the effects of the content (M+FWL vs. CHE) as well as the added dose effects of the on-line intervention program and at a 6 month follow up on reducing z-BMI in overweight African American adolescents and their parents.

Families are recruited in collaboration with local pediatric clinics, schools, and community partners such as churches and recreational centers. Families were eligible to participate if: 1) they have an African American adolescent between the ages of 11–16 years old, 2) the adolescent is overweight or obese, defined as having a BMI ≥85th and <99th percentile for age and sex, 3) at least one parent or caregiver living in the household with the adolescent is willing to participate, and 4) the family has internet access. Exclusion criteria includes presence of a medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with physical activity or dietary behaviors, already taking part in a weight loss program, or taking medication that could interfere with weight loss. It is anticipated that, approximately 520 families, will be randomized to participate in either the M+FWL or CHE conditions. This sample size allows for approximately a 25% attrition rate to maintain a final sample of at least 400 families.

3. Integration of Motivational, Behavioral, and Family-based Theories in the FIT Intervention

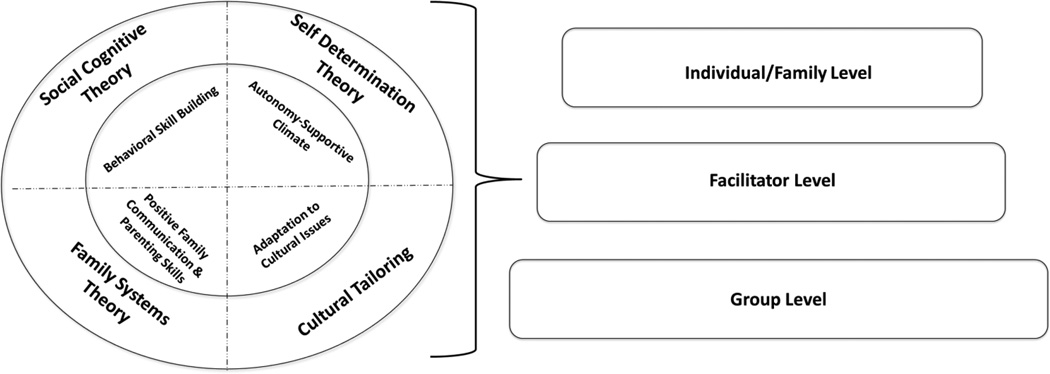

The intervention essential elements (Table 1) and curriculum matrix (Table 2) for our efficacy trial are based on a theoretical framework (Figure 2) that is novel and integrates elements from cultural tailoring, Social Cognitive Theory (SCT),56,57 Self-Determination Theory (SDT),58 Family Systems Theory (FST),59 and cultural tailoring strategies. Each of these theories is supported by empirical evidence and suggests different mechanisms for reducing obesity. FST targets positive parenting skills (parenting style, monitoring, communication); SDT teaches parents how to increase youth motivation by encouraging youth to have input and choices (autonomy-support); SCT provides the framework for building skills and self-efficacy through developing action plans that target goal setting, monitoring, and positive feedback. SDT postulates that experiences that are enjoyable and self-initiated though autonomy-supportive interactions will promote and sustain behavior change.58 Behavioral strategies from SCT, including self-monitoring, goal-setting, and skill building, are also important elements for promoting long-term lifestyle changes, but few studies have integrated choice and autonomy into their self-monitoring plans.10,37 Integration of FST also targets parenting skills for improving health behaviors in African American adolescents.11 According to FST, functional families are able to manage daily life in the context of warm and supportive family interactions.59,60 Distinct parenting styles have been defined as permissive (low control and monitoring), authoritative (moderate control and monitoring, shared-decision making), or authoritarian (high control and monitoring, rigid and inflexible).61 Authoritative parenting styles that incorporate shared-decision making, setting appropriate boundaries, providing moderate levels of monitoring, and effective conflict resolution within the context of family support have been associated with more positive health behaviors in youth20,58,62–65, and are a central component of the M+FWL intervention.

Table 1.

Families Improving Together Theoretical Essential Elements

| Theory | Essential Element | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SCT | Self-Monitoring | Parents and adolescents monitor their caloric intake, energy expenditure, and weight, using a tool of their choice. |

| SCT | Goal Setting | Parents and adolescents set specific weight-loss goals together weekly, including intake, expenditure, and sedentary behavior goals. |

| SCT | Self-Regulation Skills | Parents and adolescents learn to identify personal barriers, substitute healthier alternatives, and provide positive reinforcements. |

| SDT & FST | Communication Skills | Parents and adolescents use positive communication strategies, including reflective listening, problem-solving, and shared decision-making, to discuss weight-loss behaviors. |

| FST | Parental Monitoring and Limit Setting | Parents monitor and track adolescent self-monitoring and goals, set limits with adolescents around weight loss behaviors, and monitor implementation of family rules and rewards for adhering to weight-loss behaviors. |

| SCT, SDT, & FST | Social Support | Adolescents use strategies for eliciting social support for weight-loss behaviors from parents. Parents provide adolescents with social support for weight-loss behaviors. |

| SDT | Autonomy Support | Adolescents have choices and are provided with opportunities to give input. Parents seek input from adolescents and negotiate rules and behavior changes together. Families engage in shared decision-making. |

| SCT | Self-Efficacy | Adolescents and parents have opportunities to practice and successfully master weight loss strategies. |

| SDT | Motivation | Families provide input and build confidence in changing weight-loss behaviors. |

| Cultural Tailoring | Adaptation to Cultural Issues | Families develop action plans for resolving cultural barriers to weight loss and parenting skill development as appropriate. |

Table 2.

Curriculum Matrix for the Group-Based Program

| Week Theme |

Content | Interactive Activities | Take Home/ Family Bonding Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Run-in Week 1 Orientation |

|

|

N/A |

| Run-in Week 2 Orientation |

|

|

N/A |

| Week 1 Let’s Start Strong! |

|

|

|

| Week 2 Working Together Towards Weight Loss! |

|

|

|

| Week 3 “Together” Means Supporting One Another and Energy-In/Nutrition |

|

|

|

| Week 4 Let’s Dig In! |

|

|

|

| Week 5 Let’s Get Active! |

|

|

|

| Week 6 Get off the Couch! Please. |

|

|

|

| Week 7 Listening to Connect |

|

|

|

| Week 8 Keep it Up! |

|

|

|

Figure 2.

Theoretical Model for the FIT Intervention

At the individual/family level, families are encouraged to develop manageable goals for weight loss and caloric reduction. Participants are provided their body mass index (BMI) and associated recommended calorie levels during week 2 of the intervention. Specifically, parents and teens are provided with a recommended daily caloric intake range depending on their BMI and age. Participants then use these values to develop long and short term goals related to weight loss or maintenance, calories in and calories out. Project FIT targets five health behaviors related to caloric intake/expenditure: 1) increasing fruit and vegetable intake, 2) decreasing fast food and junk food intake, 3) decreasing sugar sweetened beverages, 4) increasing physical activity, and 5) decreasing screen time. National recommendations are promoted throughout the program and are used as a benchmark for setting weekly calorie goals. To support the attainment of weekly goals, families are encouraged to participate in activities related to behavioral and family skill building both in session and at home. These activities include weekly behavioral skill building activities (e.g., self-monitoring) and family bonding activities, which are take-home activities that support the development of positive parenting skills and communication (e.g., setting a family health goal, cooking a meal together, etc.). Importantly, families are provided with choice on methods for monitoring and completing weekly goals. For example, families are shown paper-pencil (e.g., tracking forms) and electronic methods (e.g., My Fitness Pal) for self-monitoring calories or energy expenditure and are supported in finding a tool of their choosing. Additional tools provided to the families to support behavioral and family skill building include a workbook that includes pages for each weekly session, a Calorie King journal, and a pedometer.

The M+FWL intervention integrates several established approaches for culturally tailoring interventions.66 The most successful health promotion interventions for ethnic minorities have incorporated culturally targeted and culturally tailored intervention components using multi-systemic approaches.10 Interventions that have “socio-cultural” or “deep structures” typically integrate cultural values and norms into the intervention programming and have been demonstrated by Resnicow et al. to be effective tailoring approaches for health behavior change.67,68 In the present study, peripheral strategies are used, to give program materials the appearance of cultural appropriateness by using certain images and pictures of group members. In addition, linguistic strategies are used to develop program materials that are dominant to the native culture of the African Americans.66 Furthermore, deep structures or socio-cultural strategies are integrated within the health related context of the intervention that integrate the broader social and cultural of the African American population.69 Examples of tailoring on socio-cultural and deep structure issues include addressing spirituality and cultural values related to food preferences. The present study expands on past research by integrating a unique cultural component the integrate themes such as identifying foods with special meaning, discussion of emotional eating, the pillar syndrome (i.e., role of women as caregivers for the family) and hairstyle during physical activity.40

Face-To-Face Group Sessions (both programs)

Both programs comprise 8 weekly face-to-face sessions after completing a 2-week run in period. The run in period allows for families with barriers to drop out of the study before being randomized to a treatment group condition and has resulted in retention rate of 82–91% in our previous studies with African American families.22 Participants in both programs attended a weekly 1.5 hour session for 8 weeks.

M+FWL Weekly Sessions

Two trained facilitators of which at least one is African American deliver the M+FWL intervention. All facilitators undergo extensive training that includes both didactic and hands-on, role-play components. Facilitators receive training on advanced behavioral skills related to weight loss and positive parenting and family communication strategies. Facilitators also receive extensive training on motivational interviewing skills, techniques for promoting a positive social environment, and how to target key behavioral and parenting skills in both group and individualized feedback sessions. Furthermore, facilitators are trained in cultural competency skills. All facilitators must pass a certification process, and serve as a co-facilitator prior to becoming a lead facilitator.

The M+FWL intervention is delivered one night per week over eight weekly sessions. Each group has a lead and co-facilitator. Groups have approximately 5–10 families (one parent and one child) and last approximately one and a half hours. Facilitators are provided a facilitator’s guide for each session and participate in a coaching session prior to each group session. The guides include session objectives, key content, activities, and prompts for each session. Key content was identified for each session to ensure delivery of theoretical elements. Families receive curriculum with hands-on activities that parallel the facilitator guides. The M+FWL intervention is outlined in Table 2. In the event that families are absent at a given session, facilitators conduct make-up sessions with participants either in person or over the phone depending on the participant’s preference. In addition to the group-based content, families receive individualized feedback sessions prior or following each group session that lasts approximately 10–15 minutes. During the individualized feedback sessions, families complete a checklist on the previous week’s behaviors related to diet and physical activity, and submit self-monitoring logs to the facilitator for review. These sessions provide individualized problem solving and goal setting using motivational interviewing techniques.

Comparison Program (CHE) Weekly Sessions

Families in the CHE condition also attend weekly group-based sessions for one and a half hours. Topics covered in the CHE condition include stress management, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, media literacy, metabolism, positive self-concept, and sleep. Importantly, the sessions do not include any behavioral or parenting skill components. Parents and adolescents attended the sessions together and the program follows the same schedule (i.e., is held at the same time and begins and concludes at the same time) as the M+FWL intervention. The sessions are held in difference locations to reduce the likelihood of contamination across programs.

Online Tailored Intervention

Following the completion of the group-based sessions, families are re-randomized to either the M+FWL or control online program. In online conditions, parents are the target for participation because the on-line intervention program is culturally tailored on parenting skills to assist their adolescent with continued weight loss goals. Both programs comprise 8 weekly online sessions and 3 online booster sessions (1 every 2 months), which are accessed through a secured website.

Weekly online sessions (both conditions)

Each of the 8 weekly online sessions becomes available to parents on a Saturday and closes on the following Friday. At the start of each weekly session, participants receive an automated text and email reminder to notify them that the session is accessible. To support participants’ engagement in the online program, a FIT team member (who is blind to assignment of treatment conditions) provides additional reminders to participants who do not complete the online session during the first 2–3 days of access each week (by phone, text, or email). The FIT team member also provides technical support to participants who experience barriers to completing the online sessions, including issues with login information, interrupted internet access, and limited familiarity with web-based programs or devices for connecting to the internet. No intervention-related content is delivered as part of these communications as they are only intended to support participants’ access and engagement in the online sessions.

M+FWL Weekly Online Sessions

The M+FWL online program is tailored on cultural factors, personal values, motivational profile, past and current health behaviors, and parent-adolescent communication style, (see Table 3 for examples). Both the content and the tone of the online program were based on SDT. Specifically, messages were written to support autonomous motivation. For example, the program emphasizes that behavior change is volition (both for the parent and the teen), and there is an emphasis on autonomous vs. control motivation (i.e., making change because it is personally meaningful rather than changing due to pressure, shame, or guilt). The wording of the tailored messages avoids controlling language such as “you must”, “you have to”, “it’s important”, and instead uses more autonomy supportive phrasing such as “you might consider”, and “how might this benefit you?”.

Table 3.

Description of Online Behavior Content

| Section | Content Description | Primary Tailoring Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction |

|

|

| How It’s Going | Focus on parent barriers and communication issues around being autonomy supportive and encouraging behavior. Includes the following topics:

|

|

| Weekly Strategy | Review of parenting strategy matched to the behavior (see note below). Each weekly strategy includes:

|

|

| Strategy Practice | Includes activities to help parent practice the weekly strategy. The page for each strategy is different. For example (for Push vs. Pull): “Each of the sentences below is written in a ‘push’ tone. Re-write each sentence in a ‘pull’ tone.” |

|

| Conversation Practice | Review of a motivational interviewing inspired conversation that parent could have with child about the target behavior. Example conversation incorporates the weekly strategy. Parents are provided information on how to ask child:

|

|

| Conversation Worksheet | Printable page that includes question prompts and space for writing notes. The parent uses this form to help guide their conversation with the child. |

|

| Special Features | List of items that are helpful to parents, no matter the behavior. Examples include:

|

Content copied from other program sections. |

Note: Behavior + Parenting Strategy Pairs: Energy Balance/Meeting a Calorie Goal - Active Listening; Fast Food - Reverse Role Play; Fruits & Vegetables - Increasing Engagement; Physical Activity - Escape Hatch, Volition, Choice; Time Spent Sitting - You provide, they decide; Sweet Drinks - Push vs. Pull

To facilitate autonomy supportive parent-adolescent communications about weight-related behaviors, the M+FWL online program infused an autonomy supportive parenting strategy for each of 6 target behaviors resulting in the following 6 behavior-parenting strategy pairs: 1) energy balance and meeting a calorie goal / active listening, 2) fast food / reverse role play, 3) fruits and vegetables / increasing engagement, 4) physical activity / escape hatch, volition, choice, 5) time spent sitting / you provide, they decide, 6) sweet Drinks / push versus pull (see Table 3 for more details of online content).

Parents’ participation in the M+FWL online program begins with a Welcome Session that includes a brief description of the program, and introduces the 6 health behavior-parenting strategy pairs. During this initial session, parents set a calorie goal for their adolescent and complete a tailored autonomy-supportive parenting exercise based on their current skill level for autonomy-supportive parenting.

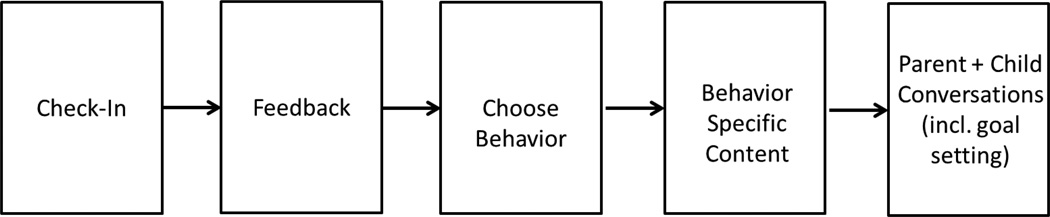

During Weeks 2–7 of the M+FWL online program, parents begin each weekly session by completing a check-in survey (see Figure 3 for flow M+FWL on-line program). This survey gathers information about the adolescent’s behavior in the 6 target areas and his/her progress toward meeting the calorie goal set during the previous week. This information is used to provide parents with real-time, tailored feedback that highlights success and areas for improvement. Parents are then prompted to select 1 of the 6 target health behaviors for that week’s session. The presentation of the behavior options is tailored around how well the adolescent is doing with each behavior as well as on the adolescent’s willingness to change each of the behaviors. Therefore, behaviors that have been most challenging and that the adolescent is ready to change are presented first, followed by behaviors that have been going well or that the adolescent is less willing to change. After selecting a behavior, parents receive education on relevancy and current recommendations or guidelines for the specific behavior. Parents also get feedback about how the adolescent is doing with the behavior, both in recent weeks and since beginning the FIT program. The delivery of this information is further tailored around the parent’s personal and cultural values as well as the adolescent’s regulatory motives for engaging in the selected behavior.

Figure 3.

Flow of a Single Online M+FLW Session

The next section of the online session focuses on barriers related to autonomy supportive parenting. This content is tailored on parent-reported barriers to communication, parent- and adolescent-reported communication, and adolescent-reported autonomy support and social support for diet and PA. This content is further tailored around the parent’s spirituality, importance of cultural foods, and ethnic identity. Parents are then introduced to the parenting strategy that has been paired with the selected behavior. After learning about the strategy, including how and when to use it, parents practice the strategy using a strategy worksheet. In the final section of a session, parents complete a conversation worksheet and set an action plan for the coming week. The purpose of this worksheet is to encourage parents to apply what they have learned about the selected behavior and the corresponding strategy with their adolescent in the coming week. This worksheet includes tips to help parents prepare to talk to their adolescent about the target behavior (e.g., “Where will you have the conversation?”), to have the conversation with their adolescent (e.g., “How will you show that you’re really listening?), and to have a response to the conversation (e.g., “How will you follow up with your adolescent to check in on his/her progress toward [goal behavior]?”).

During the final week of the online sessions (Week 8), the content focuses on reviewing ways for parents to continue supporting their adolescent. Parents complete a final check-in and receive feedback on the adolescent’s progress throughout the intervention. Parents also review the autonomy supportive strategies paired with each behavior and learn ways to apply those strategies to promote long-term health behavior change in their adolescents.

Online Comparison (Control) Condition: Weekly Online Sessions

The control online program provides parents with information about the following 8 health topics: tobacco prevention (Week 1), social media and parenting (Week 2), bullying and peer relations (Week 3), oral hygiene (Week 4), nutrition (Week 5), depression (Week 6), sleep (Week 7), and family stress (Week 8). Each week’s topic is introduced with a brief description of why it is important for adolescents’ health. Parents are then prompted to click on links to websites that provide additional information about the topic. Websites were selected based on credibility (e.g., sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, the American Psychological Association) and content readability. Websites that contained information that overlapped with the M+FWL online were excluded.

Online Booster Sessions

Parents in both online conditions complete a total of 3 booster sessions every other month. Each booster session remains accessible for a 4-week period, with the first booster session becoming available 4 weeks after the 8-week online program. The content for the booster session is chosen by the participant after the check-in survey. The choices are the same 6 topics available during the 8-week intervention. So, the content may be a repeat of something they’ve seen before, or it may not be. Even if they chose a topic as a repeat, the tailoring for that session is based on the responses from the latest follow-up survey (completed after the post on-line program), which may be different than the data provided at an earlier time point.

4. Process Evaluation

Process evaluation, which measures the extent to which an intervention is delivered as planned,70,71 is used to evaluate the dose (extent to which program content is addressed and received), reach (proportion of intended audience that participates in the intervention), and fidelity (extent to which the intervention conforms to theoretical elements) of the M+FWL intervention. By assessing these components, we can evaluate whether the group intervention adhered to the cultural and theoretical elements of the M+FWL intervention. Additionally, process evaluation will be used to examine mechanisms, through which the M+FWL intervention impacts weight related outcomes.71,72

The FIT process evaluation was developed using a systematic approach and has been previously described in detail.40 Constructs from SDT,58 SCT,57 and FST73 were integrated with principles from cultural tailoring74,75 to inform the identification of program essential elements (see Table 4). Essential elements were used to define acceptable delivery (i.e. the extent to which the program conforms to the theoretical elements) and program components were used to define complete delivery (i.e. the extent to which program components are delivered by facilitators and received by participants). Process evaluation questions related to dose and fidelity were based on definitions of acceptable and complete delivery. Additional process evaluation questions related to reach and context were also identified.

Table 4.

Process Evaluation Methods

| Measure | Program | Source | Purpose | When Collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attendance Records | Face to Face | Intervention Staff | Reach | Weekly at each session; make-up attendance data completed after each make-up session |

| Facilitator Feedback | Face to Face | Facilitators | Fidelity | Weekly; facilitators complete an electronic rating form. Results used to guide coaching sessions. |

| Individualized Feedback Checklist | Face to Face | Facilitators – M+FWL only | Dose Delivered Dose Received |

Weekly; facilitators complete during individualized feedback sessions to record delivery of feedback and tracking/goal setting and family bonding activities. |

| Observation Checklist – M+FWL | Face to Face | Trained Evaluators | Dose Delivered Fidelity – Facilitator/Group |

Weekly; external observers rate each session. |

| Observation Checklist – CHE | Face to Face | Trained Evaluators | Dose Delivered | Weekly; external observers rate each session. |

| Participant Survey | Face to Face | Participants – M+FWL only | Dose Received | Weeks 4 & 8; participants complete surveys. |

| Post-Program Interviews | Face to Face | Participants | Context Participant Satisfaction |

Selected parent-teen dyads participate in 15 minute telephone interviews |

| Psychosocial Survey | Face to Face and Online | Participants | Fidelity – Individual/Family | Baseline and post-group |

The FIT process evaluation is designed for both summative and formative purposes.76 For the face-to-face group sessions systematic observations of the weekly sessions are assessed by a trained, independent process evaluator to assess dose delivered and fidelity to theoretical and cultural elements. In addition, psychosocial surveys are conducted at baseline, post group, post online and 6-month follow up assessments to assess psychosocial mediators of program outcomes. Formative measures, such as attendance tracking, facilitator feedback, and internal observations, are summarized throughout implementation to provide formative, ongoing feedback.

The process evaluation for the FIT face-to-face sessions includes several novel aspects. First, the process evaluation is multilevel in that it assesses fidelity to theoretical elements and dose delivered across facilitator, family and group levels. Assessing theoretical elements across multiple levels will allow for a more complete understanding of how program implementation influences program outcomes. For example, it is possible that elements related to the group climate as well as facilitator delivery of theoretical constructs may influence implementation. Second, the process evaluation assesses delivery of cultural elements during the group sessions. This evaluation may aid in the identification of strategies for implementing effective culturally-tailored weight loss interventions in the future. Third, individualized feedback sessions are assessed weekly to provide insight into participant dose received; this includes assessment of parent and teen engagement in weekly tracking, goal setting, and family bonding activities. Assessment of individualized feedback sessions also provide an in depth understanding of implementing calorie goals for weight loss among participants.

5. Data Analysis Plan for Primary Outcomes

The primary aims of this study are to assess intervention effects, including average effects of the group-based M+FWL and online interventions (vs. group-based CHE and online controls) and added dose effect (i.e., group-based M+FWL and online interventions combined), on reducing BMI z-scores in overweight African American adolescents at 3 assessment periods: 1) at 8 weeks (i.e., post-group), 2) at 16 weeks (post-online), and 3) at a 6-month post-intervention follow-up. Because the group intervention involves treating multiple families in groups, random effects models will be implemented to derive unbiased estimates of treatment effects that account for potential similarities in outcomes as a function of group process.77 Each of the three aims will be evaluated with a separate random effects ANCOVA model in which 8-week BMI, 16-week BMI, and 6-month BMI is the outcome for aims 1–3 respectively, with random effects estimated for the intervention group. This approach eliminates the need for overly complex random effects that would be required of a single longitudinal model testing all treatment effects over time. Baseline BMI values will be entered as a covariate to account for the longitudinal design of the study, but the outcome for each aim will be assessed at a single time point. In the notation of Raudenbush and Bryk78 the model for the 16-week and 6 month assessment will be:

- Level 1 (Between subjects):

Eq.1 - Level 2 (Treatment group):

Eq.2 Eq.3 Eq.4

where Yijs BMI-z at a given time point for individual i in group j. Group-based treatment effects are assessed by γ01 which is the differences in mean BMI-z between those in the online control and group-based M+FWL and those in the online control and CHE (control) conditions. Individual-level online treatment effects are represented by γ10, which is the mean difference in BMI-z between those in the group-based control and the online treatment and those in the group-based control and the online control. The synergistic effect of the online treatment and the group-based treatment on BMI-z is assessed by the group × online interaction (γ11), which is the additional effect on BMI-z of receiving both the online and group-based treatment. While the effects of each intervention are evaluated with 1 parameter in this model, we will conduct an overall F-test to assess whether there is any evidence of intervention effect at each time period, the effects of the individual components will only be examined if there is an overall intervention effect. This model will first be used to examine baseline comparability between groups. In models testing the primary aims, baseline BMI-z will be included as a covariate along with baseline MVPA, age, sex, and other relevant demographics.

Research questions associated with each primary aim are assessed by intervention effects examined at each measurement period in separate but similar models. In the model predicting BMI-z at 8 weeks, the group-based treatment effect (γ01) is of primary interest. The effects of the online treatment (γ10) and the group × online interaction (γ11) provide information about the comparability of groups prior to randomization to an online condition. In a separate model, BMI-z at 16 weeks (i.e., post-online) is predicted by the online treatment effect (γ10) and by the effects of the added dose of the online intervention (γ11). A final model will test the third aim by assessing the maintenance of treatment effects and added dose effects on BMI-z at a 6-month post-intervention follow-up. The primary and secondary measures are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Anthropometric, dietary, and accelerometry physical activity data in the FIT trial

| Measure | Description | Construct Validity |

Reliability Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | |||

| z-BMI | BMI normalized to age and sex calculated from height (measured to 0.1 cm/Shorr height board) and weight (measured to 0.1 kg/SECA 880 digital scale). Calculated from Centers for Disease Control sex specific 2000 reference curves (NutStat EpiInfo) | Percentage body fat (DXA) r=0.80 (boys) r=0.78 (girls) | |

| Secondary | |||

| Waist | Measured to 0.1 cm using natural waist protocol/flexible measuring tape. | Weight r=0.92 | r=0.99 (inter-rater) |

| Skin fold | Measured at 2 sites (subscapular and tricep) to 0.5 mm using BRAND calipers. | ||

| Dietary recalls | Estimates of daily energy (calories), fat grams, fruit and vegetable intake calculated from 3 random, telephone-administered 24-hour recall interviews (2 weekday, 1 weekend day). | ||

| Accelerometry PA | Estimates of PA collected using Actical accelerometers. Body movement measured omni-directionally and recorded in 1-minute epochs during 7 days of wear. Raw data converted to METS using previously validated cutpoints. | Actiwatch r=0.93 | r=0.62 |

Note. BMI=body mass index; DXA=dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

Secondary aims

This model will also be applied to assess intervention effects on secondary outcomes at each assessment period (i.e., post-group, post-online, and 6 months post-intervention) in the FIT trial, including BMI in parents as well as waist circumference, skin fold thickness, MVPA, and dietary intake in adolescents and parents. Adjustment for multiple comparisons will be made for these analyses.

Missing data

Multiple imputation79 will be used to address missing data in the FIT trial, consistent with previous national trials.80 Multiple imputation has been shown to provide unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors and is appropriate for longitudinal data.81 The advantage of this procedure over listwise deletion is that it provides unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors under the assumption that data is missing at random. To address the assumption that data are missing at random in the FIT trial, analyses will be conducted to identify predictors of attrition. Covariates that significantly predict missingness of primary or secondary outcome data at one or more assessment periods will be included in the imputation model, along with other variables of theoretical and substantive importance. This procedure minimizes the likelihood of biased estimates and increases the plausibility of the missing at random assumption.79,82

Power

Apriori power analyses were conducted using Monte Carlo simulations with data generated according to the model described above. Based on other reports in the literature and analyses of a previous study conducted with a similar population, we assume that the ICC for treatment group is .05 and that the correlation for BMI over time is .90.11 Power was assessed for an effect size of .20, a small effect but within the range of those reported for other interventions targeting weight loss.11 These analyses found power of .96 for the main effect of the individual web-based intervention, .64 for the main effect of the group-based intervention, and .77 for the interaction effect which examines the synergistic effect of the two interventions. Thus, power is quite high for the BMI outcome, however, this is because we expect the effect size for the interaction term to be relatively small. Because it is far less stable over time, a much greater effect size is required to achieve adequate power for the secondary outcomes of MVPA and diet, for these outcomes an effect size of .40 was required to achieve over 80% power to find main effects of each intervention, and an effect size of .45 was required to have almost 80% power to find an interaction between the two interventions.

6. Study Implications

Our team has conducted several preliminary studies testing the effectiveness and feasibility of integrating positive parenting, autonomy support, motivation, cultural tailoring and behavioral skill building into brief programs for African American youth and their parents. These preliminary programs have demonstrated initial success as evidenced by high participant satisfaction and attendance rates, improvements in diet, and small reductions in BMI. This large-scale efficacy trial provides an opportunity to evaluate these variables in a larger sample along with developing deep cultural tailoring. In addition, this trial will evaluate the additive effects of a tailored parenting online intervention following a brief face-to-face family-based weight loss program. Due to the factorial nature of the study design, this study expands on past research by allowing the individual effects of the face-to-face intervention and the tailored online parenting component to be evaluated. This is one of the first studies that has the ability to test both the individual and additive effects of face-to-face group interventions and an online tailored program for parents to promote weight loss in African American adolescents. This large-scale efficacy trial will provide important and novel information to develop effective weight loss strategies for African American adolescents and their parents. Developing interventions that are easily disseminated and that incorporate technology will be important for future research that targets hard to reach underserved ethnic minorities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (R01 HD072153) funded by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development to Dawn K. Wilson, and by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32 GM081740). Please send reprint request to Dawn K. Wilson, Ph.D. at wilsondkmailbox.sc.edu. ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01796067.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Overweight children and adolescents: Screen, assess and manage. [Accessed June 5, 2008];2008 http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/training/modules/module3/text/page5a.htm.

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll M, Curtin L, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faith M, Pietrobelli A, Allison D, Heymsfield S. Prevention of pediatric obesity. Examining the issues and forecasting research directions. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The Relation of Overweight to Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Children and Adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):1175–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Must A, Anderson SE. Effects of obesity on morbidity in children and adolescents. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6(1):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores G, Olson L, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood health and health care. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):183–193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much, and who's paying? Health Aff. 2003;(Supplement Web Exclusives:W3):219–226. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trogdon JG, Finkelstein EA, Hylands T, Dellea PS, Kamal-Bahl SJ. Indirect costs of obesity: a review of the current literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):489–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resnicow K, Yaroch AL, Davis A, et al. GO GIRLS!: results from a nutrition and physical activity program for low-income, overweight African American adolescent females. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):616–631. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson DK. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(3):231–244. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilson DK, St George SM, Lawman H, Segal M, Fairchild A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(3):231–253. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnicow K, Yaroch AL, Davis A, et al. GO GIRLS!: Development of a Community-Based Nutrition and Physical Activity Program for Overweight African-American Adolescent Females. J Nutr Educ. 1999;31(5):287–289. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E. Pathways to obesity prevention: report of a National Institutes of Health workshop. Obes Res. 2003;11(10):1263–1274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeller M, Kirk S, Claytor R, et al. Predictors of attrition from a pediatric weight management program. J Pediatr. 2004;144(4):466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing RR, Anglin K. Effectiveness of a behavioral weight control program for blacks and whites with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(5):409–413. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doak CM, Visscher TL, Renders CM, Seidell JC. The prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a review of interventions and programmes. Obes Rev. 2006;7(1):111–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with 'best practice' recommendations. Obes Rev. 2006;7(Suppl 1):7–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(5):667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitlock EP, Williams SB, Gold R, Smith PR, Shipman SA. Screening and interventions for childhood overweight: a summary of evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):125–144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee K. Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2008;615(1):12–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitzmann KM, Dalton WT, Stanley CM, et al. Lifestyle interventions for youth who are overweight: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):91–101. doi: 10.1037/a0017437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilson DK, St. George S, Segal M, Schneider EM, Kugler KA. A preliminary test of a weight loss program integrating motivational and parenting factors for African American adolescents. Child Obes. 2011;7(5):379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein L, Paluch R, Roemmich J, Beecher M. Family-based obesity treatment, then and now: Twenty-five years of pediatric obesity treatment. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):381–391. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein LH, Wing RR, Koeske R, Valoski A. Long-term effects of family-based treatment of childhood obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(1):91–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemeier BS, Hektner JM, Enger KB. Parent participation in weight-related health interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev med. 2012;55(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr-Anderson DJ, Adams-Wynn AW, DiSantis KI, Kumanyika S. Family-focused physical activity, diet and obesity interventions in African–American girls: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(1):29–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bassett R, Chapman GE, Beagan BL. Autonomy and control: The co-construction of adolescent food choice. Appetite. 2008;50:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St. George SM, Wilson DK. A Qualitative Study for Understanding Family and Peer Influences on Obesity-related Health Behaviors in Low-Income African American Adolescents. Child Obes. 2012;8:466–476. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratner RE. An Update on the Diabetes Prevention Program. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:20–24. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.S1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009 Nov 14;374(9702):1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Sep 27;170(17):1566–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(4):713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whittemore R, Melkus G, Wagner J, Dziura J, Northrup V, Grey M. Translating the diabetes prevention program to primary care: a pilot study. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delahanty LM, Nathan DM. Implications of the diabetes prevention program and Look AHEAD clinical trials for lifestyle interventions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(4 Suppl 1):S66–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blixen CE, Singh A, Thacker H. Values and beliefs about obesity and weight reduction among African American and Caucasian women. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(3):290–297. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitzmann KM, Dalton WT, Stanley CM, Beech BM, Reeves TP, Buscemi J, et al. Lifestyle interventions for youth who are overweight: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2010;29:91–101. doi: 10.1037/a0017437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer LA, et al. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. Obesity Prevention Effectiveness Trial: postintervention results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 May;19(5):994–1003. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olvera N, Leung P, Kellam SF, Liu J. Body fat and fitness improvements in Hispanic and African American girls. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(9):987–996. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alia KA, Wilson DK, McDaniel T, St. George SM, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Smith K, Heatley V, Wise C. Development of an Innovative Process Evaluation Approach for the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss Trial in African American Adolescents. Eval Program Plann. 2015;49:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothert K, Strecher VJ, Doyle LA, et al. Web-based Weight Management Programs in an Integrated Health Care Setting: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Obesity. 2006;14(2):266–272. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet-based technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA. 2001;285(9):1172–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stinson J, Wilson R, Gill N, Yamada J, Holt J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(5):495–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casazza K, Ciccazzo M. The method of delivery of nutrition and physical activity information may play a role in eliciting behavior changes in adolescents. Eat Behav. 2007;8(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, Cardon G, Deforche B. School-Based randomized controlled trial of a physical activity intervention among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones M, Luce KH, Osborne MI, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):453–462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J-L, Wilkosz ME. Efficacy of technology-based interventions for obesity prevention in adolescents: a systematic review. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2014;5:159. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S39969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patrick K, Norman GJ, Davila EP, et al. Outcomes of a 12-Month Technology-Based Intervention to Promote Weight Loss in Adolescents at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7(3):759–770. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwinn TM, Schinke S, Fang L, Kandasamy S. A web-based, health promotion program for adolescent girls and their mothers who reside in public housing. Addict Behav. 2014;39(4):757–760. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Noia J, Schinke SP, Prochaska JO, Contento IR. Application of the Transtheoretical Model to Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Economically Disadvantaged African-American Adolescents: Preliminary Findings. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20(5):342–348. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Noia J, Contento IR, Prochaska JO. Computer-mediated intervention tailored on transtheoretical model stages and processes of change increases fruit and vegetable consumption among urban African-American adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(5):336–341. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.5.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson DA, Walden HM, White MA, et al. Two-Year Internet-Based Randomized Controlled Trial for Weight Loss in African-American Girls. Obesity. 2006;14(7):1231–1243. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williamson DA, Martin PD, White MA, et al. Efficacy of an internet-based behavioral weight loss program for overweight adolescent African-American girls. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(3):193–203. doi: 10.1007/BF03327547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White MA, Martin PD, Newton RL, et al. Mediators of Weight Loss in a Family-Based Intervention Presented over the Internet. Obes Res. 2004;12(7):1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson DK, Alia KA, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Resnicow K. A Pilot Study of the Effects of a Tailored Web-Based Intervention on Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Intake in African American Families. Child Obes. 2014;10(1):77–84. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broderick C. Understanding family process: Basics of family systems theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beavers WR, Hampson RB. Successful families: Assessment and intervention. New York, NY US: W W Norton & Co; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative control on child behavior. Child Dev. 1966;37(4):887–907. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kremers S, Brug J, de Vries H, Engels R. Parenting style and adolescent fruit consumption. Appetite. 2003;41(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radziszewska B, Richardson JL, Dent CW, Flay BR. Parenting style and adolescent depressive symptoms, smoking, and academic achievement: ethnic, gender, and SES differences. J Behav Med. 1996;19(3):289–305. doi: 10.1007/BF01857770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Horst K, Kremers S, Ferreira I, Singh A, Oenema A, Brug J. Perceived parenting style and practices and the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):295–304. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75(1):43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Resnicow K, Davis R, Zhang N, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on ethnic identity: results of a randomized study. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):394–403. doi: 10.1037/a0015217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Resnicow K, Davis RE, Zhang G, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on novel motivational constructs: results of a randomized study. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):159–169. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Resnicow K, Braithwaite R, Ahluwalia J, Dilorio C. Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health. In: Braithwaite R, Taylor S, editors. Health Issues in the Black Community. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Josey-Bass; 2001. pp. 516–542. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: the need for guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014 Feb 1;68(2):101–102. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:134–147. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saunders RP, Ward D, Felton GM, Dowda M, Pate RR. Examining the link between program implementation and behavior outcomes in the lifestyle education for activity program (LEAP) Eval Program Plann. 2006;29(4):352–364.73. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child dev. 1966:887–907. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Meyers DC, Mansard L. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: the ACT trial experience. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davis RE, Resnicow K. The cultural variance framework for tailoring health messages. Health communication message design: Theory and practice. 2011:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- 76.King JA, Morris LL, Fitz-Gibbon CT. How to assess program implementation. Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bauer DJ, Sterba SK, Hallfors DD. Evaluating group-based interventions when control participants are ungrouped. Multivariate Behav Res. 2008;43:210–236. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schafer J. PAN: Multiple imputation for multivariate panel data, software library written for S-PLUS. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taljaard M, Donner A, Klar N. Imputation strategies for missing continuous outcomes in cluster randomized trials. Biom J. 2008;50(3):329–345. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Enders CK. Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(4):267. doi: 10.1037/a0025579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]