Abstract

Background

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has demonstrated benefits for stress-related symptoms; however, for patients with burdensome treatment regimens, multiple co-morbidities and mobility impairment, time and travel requirements pose barriers to MBSR training.

Purpose

To describe the design, rationale and feasibility results of Journeys to Wellness, a clinical trial of mindfulness training delivered in a novel workshop and teleconference format. The trial aim is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life in people waiting for a kidney transplant.

Methods

The standard 8-week MBSR program was reconfigured for delivery as two in-person workshops separated in time by six weekly teleconferences (tMBSR). A time and attention comparison condition (tSupport) was created using the workshop-telephone format.

Feasibility results

Kidney transplant candidates (N=63) were randomly assigned to tMBSR or tSupport: 87% (n=55) attended ≥1 class, and for these, attendance was high (6.6 ± 1.8 tMBSR and 7.0 ± 1.4 tSupport sessions). Fidelity monitoring found all treatment elements were delivered as planned and few technical problems occurred. Patients in both groups reported high treatment satisfaction, but more tMBSR (83%) than tSupport (43%) participants expected their intervention to be quite a bit or extremely useful for managing their health. Symptoms and quality of life outcomes collected before (baseline, 8 weeks and 6 months) and after kidney transplantation (2, 6 and 12 months) will be analyzed for efficacy.

Conclusions

tMBSR is an accessible intervention that may be useful to people with a wide spectrum of health conditions. Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01254214

Keywords: Mindfulness, MBSR, telepsychology, telemedicine, Kidney transplantation

INTRODUCTION

In many ways, patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who are waiting for a kidney transplant are the ideal target population for non-pharmacologic stress reduction interventions. ESRD, an irreversible loss of kidney function that is fatal without replacement therapy, is a potent source of physiological, emotional and social stressors [1, 2]. Patients with ESRD have multiple medical and psychological co-morbidities [3], a complex medical regimen, dietary and lifestyle restrictions, and poor quality of life [4, 5] . As Manley and colleagues report, ESRD patients receiving ambulatory dialysis typically require 12 medications to treat 5 to 6 comorbid conditions [6]. Dialysis is an invasive, time consuming and burdensome technology, associated with anxiety, depression, pain, poor sleep, fatigue, and other symptoms [7]. Compared to remaining on dialysis, transplantation’s benefits include longer survival, more freedom to work and engage in leisure activities, and better health-related quality of life [8, 9]. However, the demand for donor kidneys far exceeds availability, and the average waiting time for kidney transplant surgery is about 4 years [10]. Because the wait for a kidney transplant is a period of declining health, high stress, and poor quality of life [11–13], interventions to strengthen transplant candidates’ abilities to cope are needed, but the interventions must fit into the constraints imposed by the demands of living with ESRD.

Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) was designed to facilitate adaptation to the stressors of living with chronic illness [14]. MBSR is grounded within a transactional model of stress where individuals appraise events and enact behavioral responses based on the appraisal and coping resources available. MBSR employs secularized Buddhist meditation practices to train participants to maintain non-judgmental awareness of their physical state, thoughts and emotions, and to respond to stressors with skillful actions as opposed to conditioned responses that can generate negative emotions and increase perceived stress. Shapiro and colleagues [15] suggest that mindfulness enables shifts in perspective leading to increased self-regulation, self-management, emotional, cognitive and behavioral flexibility, tolerance of unpleasant states, and insight. Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to reduce symptom distress in patients with solid organ transplants [16, 17], cancer [18], coronary artery disease, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome [19], and insomnia [20–22]. There is evidence that mindfulness training impacts specific brain regions, providing mechanistic insights into clinical studies showing that increased mindfulness improves symptom awareness, reduces emotional arousal, and facilitates engagement in health promoting behaviors [23, 24].

Although MBSR’s evidence base strongly supported its potential to benefit kidney transplant candidates, MBSR’s traditional classroom format was deemed a barrier to access for these patients. This article describes the development and implementation of a novel, multi-modal telephone-adapted MBSR program for Journeys to Wellness (referred to as “Journeys”), a trial to reduce symptom distress and increase quality of life in kidney transplant candidates. The design, rationale and feasibility outcomes of this trial are reported here; efficacy results will be reported elsewhere. To our knowledge, this will be the first multi-modal telephone-adapted MBSR program tested in a patient population.

METHODS

Study design overview

Journeys is a two-group, randomized, controlled trial to compare the efficacy of telephone-adapted MBSR (tMBSR) to an active control - a telephone-adapted structured support group (tSupport) for kidney or kidney-pancreas transplant candidates. Due to a limited number of eligible patients on the organ waitlist, enrollment was conducted over three years, with randomization to an intervention wave in each year followed by a year of post-transplant follow-up for candidates who received a kidney transplant.

Participants

Kidney transplant candidates were recruited through: 1) our university transplant center, 2) dialysis clinics, 3) community organizations, and 4) Internet sites (Craigslist and Facebook). Posters and over 3000 flyers were distributed through these sites. Letters informing candidates about the study were sent via our transplant center, and followed with informational calls to kidney candidates who appeared to meet eligibility criteria: 18 years and older, evaluated as eligible for kidney transplant, no previous transplants, English-speaking, literate, mentally intact, interested in attending two in-person workshops, reachable by telephone and able to use their phone for 6 weekly teleconferences. Exclusion criteria were being medically unstable or not receiving standard medical care, expected to receive a transplant in the next 3 months, serious mental health issues (suicidality, psychotic disorder, delirium), previous MBSR class or regularly practicing mindfulness meditation. Transplant candidates who were temporarily “on hold” for transplant in order to lose weight, for financial reasons or for issues related to an identified living donor were eligible.

Phone contact with interested kidney candidates was the first level of screening, to provide an overview of the study and procedures and to conduct a broad assessment of eligibility (candidacy status, age, use of telephone). Participants were asked whether they had taken an MBSR course before or currently meditated two or more times per week; none reported MBSR or a current practice. Candidates who passed the telephone screening were scheduled for in-person meetings with the enrollment coordinator who explained the study procedures in further detail, obtained informed consent, and gathered demographic and health history information. The final screening was conducted by the study psychologist who administered modules of the Structured Clinical Interview Diagnostic [25] to screen for serious mental health issues (mood and anxiety disorders, current substance use disorders and psychotic symptoms).

All Journeys participants completed an informed consent process and provided signed consent; the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. Kidney transplant candidates who enrolled in the trial are referred to as participants; the tMBSR teacher and tSupport group leader are collectively referred to as group leaders.

Sample size, randomization, blinding and analysis

Anxiety measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) – state version [26] is the primary trial outcome. The planned sample was N=60 based on a 15% attrition rate and medium to large effect sizes for anxiety and sleep from a previous trial with transplant recipients [17]. The sample was stratified by dialysis status (yes/no) and diabetes status (yes/no) prior to randomization. Randomization schedules were computer-generated using SAS, and designed using small randomly permuted blocks to promote balance within strata across treatment arms. The randomization schedule was generated by the study statistician who was masked with respect to variables other than stratification variables. Participants completed baseline assessments prior to randomization and returned materials prior to attending their assigned intervention. This is a single-blind study with blinded endpoints for physiological parameters: actigraphy-derived sleep values and salivary cortisol levels.

The outcome analyses for the Journeys trial will test the coefficient for the MBSR indicator variable in a multiple regression equation to predict the symptom or quality of life endpoints (e.g., level of anxiety) at post-intervention with the baseline symptom or quality of life score as a covariate. In subsequent analyses, multi-level modeling will examine trends over time with adjustments for stratifying variables and other covariates.

Interventions

Choice of the Experimental treatment

Planning for this study drew upon positive findings from two prior trials of MBSR with solid organ transplant recipients. These studies showed significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression and insomnia and improvements in health-related quality of life following MBSR [16, 17]. Participants in these prior studies commented that MBSR would have helped them during the waiting period prior to transplant when their health was worse, they were highly distressed, and more disabled. They also suggested that MBSR training would have been useful to better prepare them to cope with pain and distress following transplant surgery. The kidney recipients suggested that practicing MBSR techniques while undergoing dialysis could mitigate the anxiety and pain that often accompanies dialysis. However, discussion with kidney recipients raised doubts that attendance at 8 weekly 2.5 hour classes would be feasible, given the time demands and physiologic impacts of dialysis treatments.

Telephone conference calls were selected as an alternative delivery mode to reduce travel and in-classroom time. A pilot study using teleconferences for MBSR training conducted by Reibel and McCown found benefits to depression, anxiety and general distress post-intervention in a small group of women with general health issues [27, 28]. Furthermore, the use of the telephone to deliver psychosocial interventions for symptoms such as anxiety and depression has been found to be effective and improve access [29, 30]. Patients may also prefer the ubiquitous telephone to less familiar or more complex videoconference formats or online alternatives [31, 32]. Among primary care survey respondents (N=658) who were interested in receiving a psychotherapy or behavioral intervention for mental health, diet /exercise, smoking cessation or pain management, 62% were interested or would consider telephone-delivered treatment, and 50% were interested in or would consider internet delivery [32]. Survey results showed that age, cost, and pain are barriers for face-to-face therapies, and that people with these characteristics often prefer telephone therapy. Telephone delivery was also supported by findings from a focus group-based needs assessment with dialysis patients and their families; these patients and caregivers viewed telephone-based approaches very positively [33].

The goal in creating the tMBSR program for the Journeys study was to make the course more accessible for patients with ESRD while adhering to the recommended prescribed elements of MBSR, and without introducing new or proscribed elements. Accessibility and patient comfort were major concerns since many candidates have significant co-morbidities and limited mobility, and for survival they must travel to dialysis centers three days a week for 3-hour dialysis sessions. The tMBSR development team included a certified MBSR teacher with advanced training who had previously completed a pilot program of telephone-delivered MBSR with a small group of healthy adults (DR), an MBSR teacher who specializes in delivering the program to people with significant disability (Don McCown), an MBSR teacher with advanced training who had taught 9 MBSR courses in our previous trials (TP), a health psychologist experienced with MBSR and issues in kidney transplantation who had coordinated two previous MBSR trials (MR-S), and a quality of life scientist with many years of experience in transplant research and MBSR (CRG). Roundtable discussions, teleconference calls and emails were used for team communications to produce the tMBSR workbook.

The intervention was conceptualized as having a multi-modal “book-end” design with in-person workshops at the beginning and end, and six weekly teleconferences in-between. The rationale for this design is that face-to-face MBSR teacher interactions ensure that yoga poses could be appropriately modified to meet the needs of people with physical disabilities, and that group cohesion and support would be facilitated by workshop interactions, and maintained via group teleconference. Also, a traditionally delivered MBSR course is 8 weeks, enabling participants to spend time to experience, share and obtain feedback from both the teacher and their group as they build their mindfulness practice. This design reduced travel time by 75% (2 vs. 8 round trips) and on-site classroom time by 62% (10 vs. 26 hours).

Choice of the control treatment

There is no placebo pill for control groups in MBSR trials. Use of a waitlist or treatment as usual control for MBSR has been criticized for failing to control for powerful impacts of non-specific effects such as instructor attention and group support [34]. These and other common, non-specific factors in non-pharmacologic mental health therapies have been shown to contribute up to 30% of the variance in patient improvement. Key factors include instructor attention and the therapeutic alliance [35] and, for group interventions, group support and sense of belonging [36]. Fortunately, there is a growing body of evidence to support the use of the telephone in establishing a therapeutic alliance. Working Alliance Inventory scores were high and predicted improvement in distress, depression and symptoms of post-traumatic stress in a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (t-CBT) for N=46 hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors [37]. Group support has been described as a critical ingredient in traditionally-delivered MBSR [28], and qualitative studies confirm that shared experience and group support contribute to the health outcomes of MBSR [24, 38, 39]. There is also evidence that social support can be fostered through the use of telephone support groups to reduce loneliness and isolation for people with blindness [40], children and families who are seropositive for HIV [41] and in a telephone-delivered behavioral weight loss program for women in rural areas [42].

Other factors supporting the use of an active, but non-specific intervention for MBSR are consequences of lack of blinding. When participants are aware of their treatment group, randomization to usual care can lead to disappointment, high rates of dropouts, or competitive cross-over behavior (reading about MBSR or taking publically available MBSR courses) [43]. Therefore, the Journeys control was conceptualized as a telephone-adapted, structured support group (tSupport) to provide attention from a facilitator, group support and structured study activities to balance the treatment arms with respect to the known non-specific effects of MBSR [34, 44]. In designing tSupport, the goal was to provide a content-driven and highly structured intervention with an attentive instructor to elicit a positive group experience and prevent lengthy or pervasively negative discussions of problems.

Materials and procedures

tMBSR course materials and conduct

As in a standard MBSR class, tMBSR participants received recordings of practices in the teacher’s voice to use at home, a copy of Full Catastrophe Living [14] and a workbook. In addition, Mindful Movement and Stillness© DVDs [45], which included adapted yoga poses and movements for standing, seated, or reclined in-bed positions, were scripted and recorded for this study and provided to tMBSR participants. The tMBSR Workbook for Journeys to Wellness is both a course guide and an educational workbook for participants, with content drawn from the standard MBSR curriculum[46]. The tMBSR workbook was produced in a binder format, organized by week with tabs. Each of the 8 week’s materials included an overview of the current workshop or teleconference, materials related to discussions in class (e.g., a visual puzzle like the 9-dots exercise, related poetry), a checklist of home assignments to complete in the upcoming week, worksheets for home assignments (e.g. write-in pleasant events calendar) and demonstration materials (e.g. diagrams of yoga postures, in sequence).

As noted above, tMBSR is a bookend program; in-person 5-hour workshops in weeks 1 and 8 are separated by 90-minute teleconferences in weeks 2 through 7. The first MBSR workshop was designed to: (1) introduce participants to the techniques of MBSR in an in-person environment; (2) create a cohesive and supportive group experience that would foster acceptance over the eight weeks; (3) provide the teacher with opportunities to build rapport with participants; and (4) provide the teacher with opportunities for hands-on work with participants and to assist with modification of activities as needed for this population, e.g. assess mobility and balance issues and recommend tailored adaptions for yoga poses. The introductory workshop (week 1) included elements from a traditional first class (introductions, discussion of group norms and confidentiality, raisin exercise, practice of body scan) and incorporated introductions to other practices such as yoga, walking and sitting meditations. Mindful eating was introduced at lunch. Teleconference calls during weeks 2–7 included check-ins and discussion of practice and homework from the previous week, practice of techniques as a group, and group discussions of mindfulness. The workshop in week 8 was a Day of Mindfulness Retreat which included observing silence, sitting meditations, yoga, body scan, mindful lunch, walking meditation, and group sharing after silence was dissolved. An outline of the tMBSR program is shown in Table 1. Honoring physical limitations and strategies for adapting yoga poses for problems with balance or mobility (e.g. seated in a chair instead of standing or lying down) were emphasized both in-person and during teleconferences. tMBSR provided 19 hours of class time (including workshops and teleconferences), compared to 26 hours for standard MBSR (classes plus retreat). This reduced time was intentional, as 2.5 hour conference calls and a workshop longer than 5 hours were deemed too tiring for this target population.

Table 1.

tMBSR Course Elements

| Week 1a | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welcome, introductions and practice |

Perception and creative responding |

Being present | Stress reactivity | Responding to stress |

Communication | Feeling at home wherever we are |

Day of mindfulness retreat |

| Class activities | |||||||

| Welcome Overview Grounding meditation and discussion (dyads) Close eyes and reflect one word about being here Guidelines What brought you here and introductions Definition of mindfulness Raisin exercise and discussion Body scan and discussion (dyads) Yoga (floor) Mindful lunch Walking meditation and discussion Sitting meditation and discussion (dyads) Yoga (on chair or standing) Information for teleconference calls, assignments |

Welcome Silent meditation Roll call Body scan Discussion of body scan Dialog about mindful eating Breathing space instruction Perception: 9 dots, old woman (Gestalt shift) Sitting meditation: awareness of breath Discuss sitting meditation Tips for body scan Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Silent meditation: condition of body now, mind now Roll call, describe self with word or phrase Sitting meditation - awareness of breath Discussion of sitting meditation Dialog: mindful daily activities Yoga (floor) Discuss floor yoga Dialog: Body scan and sitting meditation in last week, problems, changes Review pleasant events Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Silent meditation Roll call Formal sitting meditation (awareness of breath, body sensations, sound, thoughts) Dialog about sitting meditation Walking meditation Yoga (floor) Dialog: What are people seeing, feeling, learning from body scan and yoga? What is the effect of yoga on body scan? Review unpleasant events Monkey story (how to trap a monkey, FCLb, p 39) Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Silent meditation Roll call Yoga (standing) Sitting meditation (breath, body, sounds and thoughts through choiceless awareness) Questions about sitting meditation Dialog: Midway check, letting go of expectations, awareness of a stressful situation, walking path) Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Welcome Silent meditation Roll call Yoga (standing) Sitting meditation (loving kindness) Questions about sitting meditation Dialog: Mindful communication, difficult communication (what happened), different styles Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Silent meditation Roll call Body scan Sitting meditation: awareness of breath, forgiveness practice, loving kindness Questions about sitting meditation Walking meditation Dialog: What happened with your practice? What mindful or unmindful choices did you make? Was it a positive or negative experience? What were you thinking in the moment? Discuss retreat Assignments, poetry, moment of silence |

Welcome Instructions for silence Sitting meditation Yoga (standing, floor) Body scan Walking meditation Sitting meditation Mindful lunch Walking meditation Sitting meditation (loving kindness) Yoga (standing) Dissolve silence Mindful communication Group sharing about MBSR experience Goodbyes |

| Home assignments: formal practice, informal practice, reading and writing | |||||||

| Listen to the Body scan recording for 6 days _______________ Eat at least one meal or snack with full awareness _______________ Wheel of Life, for your own use, not to share Nine Dots Puzzle Read introduction and chapters 1, 2 and 5 in Full Catastrophe Living (FCL)b |

Body scan 6 days Sitting meditation 10 minutes each day, with CD or on your own, at a time separate from body scan _______________ Breathing space practice 3–5 minutes each day, coming to your breath at work, home or wherever you can Bring mindfulness to routine activities, e.g. brushing your teeth, washing dishes, etc. _______________ Pleasant Events calendar for the week, one entry per day Read Chapters 3 and 4 in FCL |

Alternate the body scan with yoga (floor) (30 min DVD) 6 days Sitting meditation 10 minutes each day, at a time separate from body scan _______________ Breathing space practice 3–5 minutes each day, coming to your breath at work, home or wherever you can _______________ Unpleasant events calendar, one entry per day, bring to the conference call Read chapters 11- 13 in FCL |

Alternate sitting meditation and yoga (floor) for 6 days _______________ Breathing space practice 3–5 minutes each day, coming to your breath at work, home or wherever you can Notice stress reactions during the week, without trying to change them in any way Bring mindfulness to a routine walking path _______________ Read chapter 24 in FCL Complete the Midway Check from your notebooks on the day of and prior to the start of the conference call |

Alternate sitting meditation with either the body scan or yoga (floor or standing) for 6 days _______________ Bring awareness to moments of reacting and explore options for responding with greater mindfulness and creativity - do this in meditation practice as well _______________ Fill out the Difficult communications calendar, bring to the conference call Read chapters 17- 20 in FCL |

Alternate sitting meditation with the body scan and/or yoga, using any of the CDs or DVDs _______________ Expand your inquiry beyond food to what you take in through your eyes, ears and nose – look at the diet of TV, newspapers, bad news, air pollution, etc. _______________ Read chapter 31 in FCL |

Practice on your own without the CDs and DVDs, as best you can _______________ Do those practices that are best for you _______________ Read chapters 33– 36 of FCL now or in the future Prepare for the mindfulness meditation retreat – mostly silent Consider how you will bring mindfulness forward into your life |

N/A |

Telephone-adapted Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (tMBSR) weeks 1 and 8 were in-person workshops, 5 hours each; all others were 90 minute teleconferences.

Kabat-Zinn, J., & University of Massachusetts Medical Center/Worcester. Stress Reduction Clinic. (1990). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, N.Y.: Delacorte Press.

tSupport materials and conduct

The Journeys control was a telephone-adapted structured support group to provide attention from a facilitator, group support and structured study activities to balance the treatment arms with respect to the known non-specific effects of MBSR [34, 44, 47]. After discussion with the tMBSR development team to determine the overall structure and content of tSupport, a certified life coach and highly-skilled group facilitator and kidney transplant recipient (PK) joined the health psychologist to design tSupport and serve as the group leader. The tSupport development team communicated through in-person meetings, calls, and emails to draft, revise and finalize agendas and weekly hand-outs. Fidelity checklists were created from the agendas and notes from the group leader from the initial delivery of the tSupport intervention; fidelity checklists were then used in two subsequent tSupport groups.

Interpersonal communication skills and how to select health resources were selected as generic skills for tSupport that would not overlap with cultivating mindful awareness, could be modeled and discussed in a group, be documented and delivered from a treatment manual, and be useful to participants. To approximate the class-like, psychoeducational structure of tMBSR, skill-building with homework assignments were included. The group leader used coactive coaching methods for course delivery including assessment, encouragement, eliciting client-generated ideas and related stories, discussing strategies, developing plans and celebrating successes [48]. tSupport was delivered by an experienced group leader who was familiar with issues in ESRD and transplantation, and able to skillfully avoid pervasively negative discussions of health problems. For all weeks, topics were introduced though lecturettes by the facilitator, followed by elicited comments and group discussion. tSupport homework consisted of topic-based homework assignments from the leader or participant-generated personal action commitments and brief exercises of reflection and note-taking to prepare for the next call. Homework assignments were designed by the leader in week 1, 6 and 7, but were individual action commitments in other weeks. The final workshop had the tone of a celebratory reunion.

The tSupport agendas for each week followed a common sequence: roll-call and greetings, review of home assignments (assigned by the group leader) and/or action commitments (personal homework assignments) from the previous week (See Table 2), presentation of new content by the leader, group discussion of new content, creation and sharing of action commitments for the coming week, and a summary conclusion statement by the group leader. As an example, the initial tSupport workshop included a welcome by the leader, introductions, orientation to group topics, conversation “starters,” a listening exercise, and home assignments. Additionally in week 1, the leader guided the group to create group norms and review expectations of confidentiality. An outline of the tSupport intervention is shown in table 2. Since those assigned to tMBSR received materials in week 1, participants in the tSupport intervention received an attractive notebook and pen to record notes or homework assignments. The main focus of the tSupport content was communications, but no singular book about communication that matched the tSupport content and intent could be identified. Therefore, weekly handouts were provided, and participants were given a resource book of their choice in week 8, e.g. a kidney-friendly recipe book or a popular book about communication. Weekly agendas and hand-outs were mailed to participants each week, prior to teleconference calls.

Table 2.

tSupport Course Elements

| Week 1a | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting conversations |

Active listening | Nonverbal communication |

Perception and communication styles |

Dealing with difficult people |

Selecting resources | Technology and communication |

Reunion, assertive style, “I” messages |

| Welcome Introductions Overview - topics Teleconference norms Teleconference procedures Conversation startersb list and discussion, e.g. Are you comfortable as a leader or a follower? Best communicator – who is the best you’ve met or seen? Why? Listening testc exercise Home assignment Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Lecturette and read Please just listend aloud followed by group discussion Conversation: observations of conversations this week, emphasis on questions from homework Generation of action commitments Other home assignments Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Action commitments from last week Lecturette: Nonverbal communication (facial expression, eye contact, tone of voice, pace, personal space, etc.) Conversation about experiences of nonverbal communication Generation of action commitments Other home assignments Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Action commitments from last week Lecturette: Perceptions of purpose of communication often differs, e.g. male/female communication Conversation: examples of communication with misperceptions or misunderstood purposes Generation of action commitments Other home assignments Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Action commitments from last week Lecturette: Difficult peoplee (indecisive, know-it-all, agreeable, complainer, negativist, etc.) Conversation: Examples of conversations with difficult people Generation of action commitments for next week Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Action commitments from last week Lecturette: what are resources? People, places and things as resources. National Institutes of Health guidelines for selecting medical resources onlinef, avoiding “quackery,” confidentiality online. Conversation: good resources. Generation of action commitments Other home assignments Overview of next week’s topic |

Welcome Roll-call Action commitments from last week Lecturette: Electronic technology - connected and disconnected; cell phones, conference calls, social networking Conversation: How does technology affect the quantity and quality of interpersonal communication Generation of action commitments Other home assignments Book selections Overview of reunion |

Welcome Distribution of resource books from week 7 Roll-call Review agenda Action commitments from last week Lecturette: Resource list generated by class in weeks 6 & 7 (hand-out) Lecturette: Assertive communication Conversation: Assertive communication examples Conversation: Practicing “I” messages Reading and discussion: Six Conversationsg Adjourn |

| Homework assignments | |||||||

| Group assignment: Observe people having conversations this week. Reflect on: (1) What does it mean to really listen? (2) How do you feel when you are really listened to? (3) What gets in the way of good listening? (4) What new listening skill would you like to adopt? Read Please just listend |

Individual action commitments Prepare for next call: (1) Why is nonverbal communication important? (2) What nonverbal behaviors do you typically use in conversation? (3) What nonverbal behaviors may be difficult to interpret? (4) How does culture affect nonverbal communication? (5) Is there a nonverbal communication you’d like to change? (6) What nonverbal skill would you like to adopt? |

Individual action commitments Prepare for next call: (1) How do your own expectations affect your communication style? (2) What can you do to listen for the purpose of conversation? (3) What do you typically do if you don’t agree with another person’s view- point? (4) What have you noticed about how men and women communicate differently? (5) What challenges do you have in seeking to understand? |

Individual action commitments Prepare for next call: (1) What types of difficult people have you interacted with lately? (2) What are their reasons for “being difficult?” (3) How do they communicate with you? (4) How do you respond to difficult communication? (5) What are some strategies for communicating with difficult people? (6) What strategies would you like to try out in the next week? |

Individual action commitments Prepare for next call: Pay attention to how many times you interrupt or are interrupted this week. |

Group assignment: Bring a credible health or communication resource to share Prepare for next call: (1) How have digital technologies affected your communication with others? (2) How have they improved your life? (3) What have they made worse? (4) How has “being wired” affected social connections? Select 2 books from list provided (communication or transplant or renal diet) for staff to provide at reunion. |

Group assignment: Observe the quality and quantity of your digital usage and determine if it’s the right balance for you Prepare for the next meeting: Take the assertive, passive, aggressive communication quiz and bring to the reunion |

N/A |

Telephone-adapted Structured Support weeks 1 and 8 were in-person workshops, 1.5 hours each; all others were 60 minute teleconferences

Adapted from “Conversation starters.” Family table topics. http://www.familytreemd.org/files/387_TFT%20Conversation%20Starter%20FLYER.pdf Accessed 10/30/13

Graf, LA, Perrachione, JR (1983). Effective listening: an exercise in managerial communication, Developments in Business Simulation & Experiential Exercises, 10, 17–20.

Swick, J. (2008). Please just listen. Poem hunter. http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/please-just-listen/ Accessed 21 March 2014.

Adapted from Benjamin, SF (2008). Perfect Phrases for Dealing with Difficult People: Hundreds of Ready-to-Use Phrases for Handling Conflict, Confrontations and Challenging Personalities. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Adapted from “10 Things to Know About Evaluating Medical Resources on the Web.” 2006. National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). http://nccam.nih.gov/health/webresources/ Accessed 21 March 2014.

Klein, D. (unknown). Six Conversations. DesignedLearning® a Peter Block Company. http://www.designedlearning.com/six-conversations/ Accessed 21 March 2014.

Duration of workshops and teleconference calls were intentionally limited based on the amount of content, allowing time for facilitated discussions that did not become tangential and to avoid story-telling. In-person tSupport workshops were held in weeks 1 and 8, for 90 minutes each, in a conference room. Weekly teleconferences in weeks 2–7 were one hour long. Whereas the class time for tSupport (workshops and teleconferences combined) was only 9 hours versus 19 hours for tMBSR, the group discussion times were comparable, as approximately half of the tMBSR time both at workshops and in teleconferences was spent practicing meditation techniques.

Course delivery and shared materials

Shared materials and processes for teleconference calls were developed for use by both groups. Simple instructions for teleconference calls, including a wallet card with the toll-free number and numeric password, were provided to all participants at the first workshop. To protect against cross-contamination between interventions, each group was assigned a unique password. Some participants were employed and some received dialysis, so in-person tMBSR and tSupport workshops were scheduled on Sundays when dialysis clinics are closed. Teleconferences for each intervention were held on different weeknights so that study staff could monitor and assist if needed. The tMBSR teacher and tSupport facilitator initiated conference calls and had simultaneous access to study staff by a separate phone line and by email or text messaging during each teleconference, and study staff was able to join the call if necessary.

Participants discussed and received a list of norms for teleconferences at their first workshop. The teleconference norms were in addition to standard guidelines for group interventions (maintaining confidentiality, notifying the leader in advance of absences, respecting each other’s’ voices) and included technical considerations such as stating your name when speaking, calling from a quiet space to reduce disruptions and to protect privacy of others, and to use the mute button when not speaking. Teleconference norms were equivalent in both groups, except that tMBSR participants were given instructions to use the speakerphone function while doing yoga, body scan or other meditations. Norms are shown in figure 1. It was anticipated that some participants would require the temporary use of cell phones or phone cards provided by the study because their home phone or cellular service was limited, or because a phone was not available during dialysis treatment. Written and phone reminders were provided by study staff 24 to 48 hours in advance of all in-person meetings and teleconferences.

Figure 1.

Teleconference norms for tMBSR

To promote treatment fidelity, and to provide a means of measuring it, course materials (tMBSR workbook, tSupport agendas, hand-outs) for each intervention were prepared in advance of the first of three waves of the study. The group leaders and staff documented (in writing) any changes applied during course delivery in the first wave of the study; a final master fidelity checklist for each group was prepared by staff for use in waves 2 and 3.

Settings and logistics

tMBSR and tSupport workshops were held simultaneously in a University research building with ample free parking. Participants were welcomed by study staff and trained student volunteers who verified that pre-intervention data was collected and escorted participants to their assigned interventions. tMBSR participants were invited to bring a pillow/blanket or a yoga mat and met in a very large multipurpose room. tSupport participants were seated at a large table with name tents, notepads and pens, and a whiteboard in a conference room. Coffee, tea, water and light snacks suitable for a renal diet were provided at all in-person workshops to foster a welcoming atmosphere in both groups, and to provide nutrition for people with diabetes. In weeks 2–7, participants dialed in for teleconferences from their home, dialysis clinic, or from another convenient location.

Outcome Assessment

There are two main Journeys data collection forms: a history and clinical information form completed by interview at pre-randomization baseline and a health and attitudes outcomes questionnaire completed three times (pre-randomization baseline, end of the 8-week intervention and 6-month follow-up). If the participant received a transplant, additional health and attitude questionnaires were collected at 2 and 6-months after transplant surgery. The 16-page paper and pencil health and attitudes questionnaire contained the primary and secondary outcome measures: anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory - STAI) [26], depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression) [49]; insomnia (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) [50]; and health-related quality of life (Short-Form-12 v2) [51]. Potential mediators and additional symptom scales were also collected on the questionnaire. Mediators included mindfulness measured by the 15-item Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), an assessment of the frequency of mindful states in everyday life [52]; worry measured by the 16-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ), an assessment of excessive or uncontrollable worry [53] and perceived stress measured by the a 14-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14), an assessment of the extent to which situations in one’s life are perceived as stressful [54]. Fatigue was measured by the 7-item PROMIS-Fatigue Short Form v1.0 (7a), an assessment of the frequency of feelings of physical or mental energy, tiredness or exhaustion [55]. The effects of kidney disease on daily life and the burden of kidney disease were measured by two subscales of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life - Short Form (KDQOL-SF) [56], the 4-item Impact Subscale and the 8-item Burden Subscale. Two items addressing participants’ treatment preferences and expectations of intervention usefulness were created for this study. Two objective assessments, actigraphy and salivary cortisol measurements were collected at baseline and again at the end of the intervention. Objective assessment of sleep quantity and quality was obtained using actigraphy for 7 days prior to the interventions and again during the final week of active treatment. Actigraphy is a method to collect sleep/wake data using computerized, wristwatch-like devices to record movement, and then employ computer algorithms to convert patterns of motion into sleep measurements. Actigraphy has the benefits of prolonged observation time and a natural sleep environment. It been validated against the more costly and intrusive laboratory-based sleep evaluation method, polysomnography. During each day of actigraphy monitoring in Journeys a sleep diary was completed upon awakening. Salivary cortisol samples were collected as an objective biomarker of stress for three days at prior to the interventions and again during the final week of active treatment. The procedures for actigraphy and home collection of salivary cortisols were explained during the informed consent interview. The health and attitudes questionnaires, actigraphy and sleep diaries, and salivary cortisol measurement kits, were delivered to participants and returned to the study by mail.

Data forms and participant interactions were monitored by study staff or group leaders for potential adverse events, e.g., reported hospitalizations, which were tracked and reported to a medical monitor. No adverse effects related to the interventions were reported.

Assessment of Feasibility and Acceptability

Intervention attendance was collected by roll-call and recorded on weekly rosters. Attendance was further verified by conference call records provided by the teleconference vendor, which provided confirmation when a participant joined, discontinued or rejoined a call. Group leaders rated each participant’s engagement at the end of the 8-week intervention. High engagement was defined as: The participant actively participated or demonstrated practice or use of skills from the class meetings and calls,” and was rated on a 5-point scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. Participants’ treatment preferences and expectations of intervention usefulness were assessed on the health and attitudes questionnaires. Participants were provided with a comments section on the post-intervention questionnaire to provide additional comments about their experiences. Treatment fidelity was measured by tallies of prescribed course elements on intervention checklists by group leaders, with weekly calls and occasional live monitoring by the health psychologist. Handwritten notes and emails from group leaders were also used to document any deviations from intervention checklists, which were summarized narratively.

Data analysis

This paper presents feasibility outcomes including attendance, engagement, treatment preference, satisfaction and expectation of benefit and treatment fidelity. Descriptive statistics, t-tests (for continuous data) and Mann-Whitney U or Chi-square tests (for categorical or not normally distributed data) were used to compare attendance, participant engagement and treatment preference, fidelity and satisfaction between groups.

RESULTS

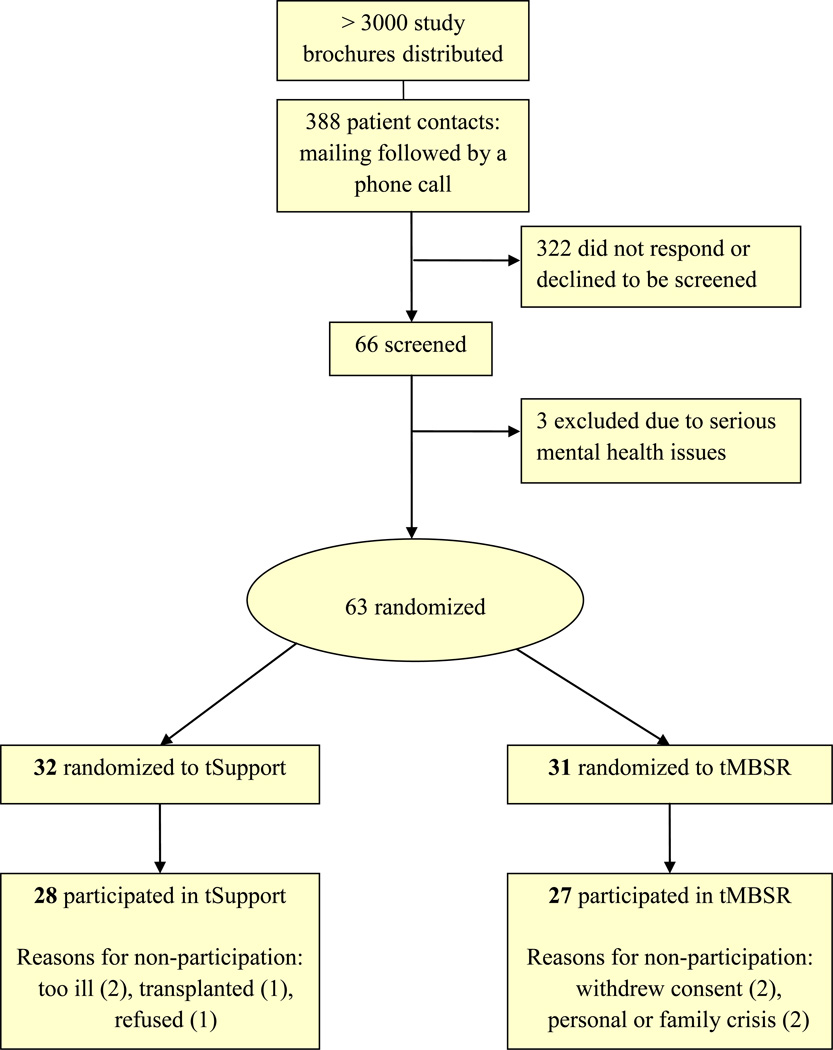

The sample consisted of 63 adult kidney transplant candidates. Participant flow is depicted in Figure 2. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 3. Participants were mostly older adults, on average 53 years old (range 26 to 85 years), and slightly more than half (57%) were women. About 30% of were minorities, 46% had diabetes, 57% were on dialysis, and 81% had hypertension or another form of cardiovascular disease in addition to their ESRD. Groups were similar for the most part, however the proportion of men was higher in tSupport than in tMBSR (56% vs. 29%).

Figure 2.

Participant Flow Diagram

Table 3.

Characteristics of kidney transplant candidates at time of randomization

| Total, N=63 Mean ± SD |

tMBSR, n=31 Mean ± SD |

tSupport, n=32 Mean ± SD |

p values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 or t | |

| Age | |||||||

| Years (range 26 to 85) | 52.8 ± 11.7 | 51.7 ± 12.1 | 53.8 ± 11.4 | .468 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 36 | 57.1 | 22 | 71.0 | 14 | 43.7 | .029 |

| Male | 27 | 42.9 | 9 | 29.0 | 18 | 56.3 | |

| Race (self-report) | |||||||

| White or European American | 45 | 71.4 | 21 | 67.7 | 24 | 75.0 | .159 |

| Black or African American | 10 | 15.9 | 8 | 25.8 | 2 | 6.3 | |

| American Indian /Alaskan native | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Asian American | 5 | 7.9 | 1 | 3.2 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Other/ multi-racial | 2 | 3.2 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino | 62 | 98.4 | 30 | 96.8 | 32 | 100.0 | .306 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Work status | |||||||

| Full-time | 23 | 36.5 | 9 | 29.0 | 14 | 43.8 | .175 |

| Part-time | 9 | 14.3 | 5 | 16.1 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Retired | 11 | 17.5 | 5 | 16.1 | 6 | 18.8 | |

| Disabled | 15 | 23.8 | 7 | 22.7 | 8 | 25.0 | |

| Other | 5 | 7.9 | 5 | 16.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Dialysis | |||||||

| Hemodialysis | 30 | 47.6 | 13 | 41.9 | 17 | 53.1 | .200 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6 | 9.5 | 5 | 16.1 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Pre-dialysis | 27 | 42.9 | 13 | 41.9 | 14 | 43.8 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| Type I | 10 | 15.9 | 6 | 19.4 | 4 | 12.5 | .651 |

| Type II | 19 | 30.1 | 8 | 25.8 | 11 | 34.4 | |

| No diabetes | 34 | 54.0 | 17 | 54.8 | 17 | 53.1 | |

| Hypertension or history of cardiovascular disease | |||||||

| Yes | 51 | 81.0 | 25 | 80.6 | 26 | 81.3 | .951 |

| No | 12 | 19.0 | 6 | 19.4 | 6 | 18.8 | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||||||

| Average BMI (range in this sample 18.6 – 43.9) | 27.8 ± 5.5 | 28.5 ± 5.1 | 27.2 ± 6.1 | .373 | |||

| Healthy weight (18.5 - <25) | 23 | 36.5 | 6 | 19.4 | 17 | 53.1 | |

| Overweight (25 - <30) | 19 | 30.2 | 13 | 41.9 | 6 | 18.8 | |

| Obese (≥30) | 21 | 33.3 | 12 | 38.7 | 9 | 28.1 | |

| Charlson co-morbidity score * | |||||||

| Range in this sample: 2 to 8 | 4.02 ± 1.7 | 4.16 ± 1.8 | 3.88 ± 1.7 | .515 | |||

Each serious co-morbidity is given a weight from 1 to 6 based on chart review and ICD-10 codes [64]

Note: Column percents may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Attendance

Participants were randomized to tMBSR (n=31) or tSupport (n= 32). In each treatment group, 4 persons (13% of each group) did not attend any of the intervention sessions (in-person or teleconferences). Collectively, reasons for non-attendance were deteriorating health (n=3), transplant surgery (n=1), family emergency (n=1) or refusal (n=3). In order to attend the workshops, fourteen of 63 participants (22%) needed study-provided taxis. Class sizes ranged from n=3 to 13 (tMBSR) and from n=5 to 12 (tSupport).

Based upon all randomized, attendance at 3 or more of 8 classes was 84% (n=26, tMBSR) and 88% (n=28, tSupport). For the n=55 participants who attended at least one class, attendance rates were high, averaging 6.6 ± 1.8 tMBSR sessions and 7.0 ± 1.4 tSupport sessions. Perfect attendance was attained by 36% of tMBSR and 38% of tSupport participants. For those who attended, there were no significant differences between groups for numbers of sessions attended (p = 0.472).

Treatment preference, satisfaction and expectation of benefit

During enrollment, all participants were given a very brief description of the two treatments. At the end of the intervention, participants were asked to recall their treatment preference from when they enrolled in the study (tMBSR, tSupport or no preference), and having completed the intervention, how satisfied they were with their assigned treatment, and their expectation of benefit from the class. Preference at time of enrollment was reported by 50 of the 55 participants who attended at least one class, and did not differ by treatment group (p=0.340); 54% stated no treatment preference, 40% preferred to be assigned to tMBSR, and only 6% preferred tSupport. tMBSR was preferred by 30% of those assigned to tMBSR and by 48% of those assigned to tSupport.

Participants (n=51) rated their satisfaction with their assigned group post-intervention on a scale where 0 = very dissatisfied and 10 = very satisfied. Ratings were high in both groups. Satisfaction for tMBSR (n=24) was 8.83 ± 1.71 (range = 3–10) and 8.07 ±2.13 (range= 2–10) for tSupport (n=27), and not statistically different between groups (p = 0.17). Expectations of benefit of the interventions was assessed post-intervention with the following item post-intervention: Please rate how much you expect the techniques and information presented in your group will help you cope with your health in the future. Expectations were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Ratings of expected benefit were significantly higher for tMBSR, averaging 4.17 ± 0.82, compared to 3.37 ± 1.04 for tSupport, and expectations of benefit were rated as 4s or 5s by 83% of tMBSR participants, compared to only 48% of tSupport participants, with a significant Chi-square for linear association (p = 0.005) for greater expectation of benefit in the tMBSR group.

Participant engagement

At the completion of each 8-week class cycle, group leaders were asked to rate each participant from their respective group for how engaged they were in the class, independent of their attendance. Group leaders rated their participants similarly with tMBSR engagement mean = 4.0 ± 0.9 and tSupport mean = 4.1 ± 0.8 (no significant difference). Individual tSupport homework action plans were adopted as planned. For example, in week 3 (nonverbal communication), individual action commitments included: “Observe nonverbal communication in <dialysis clinic> setting with patients and providers,” “Pay attention to nonverbal behaviors in group dynamics at work, “ and “Try to have better posture and look up when communicating with others.” Leader-designed homework assignments are described in Table 2. With the exception of absences from the group, all participants reported that they had engaged in their assigned reflection or preparation for each call, and all reported progress on their action commitment from the previous week, even if progress meant that they had encountered a challenge and requested feedback. Notes from the tSupport facilitator included, “Group obviously did assignment in advance – very thoughtful insights and great participation,”

Treatment Fidelity

Total class delivery time in wave 1 was 1140 minutes (19 hours, as planned), but was slightly less in wave 2 (-25 min; 2% difference) and wave 3 (-53 min; 5% difference). A greater degree of physical disability was observed in waves 2 and 3, which resulted in time adjustments to start workshops late (e.g. 15 min wave 3, weeks 1 and 8) or end early (e.g. 15 min, wave 2), but teleconference class times deviated from 90 minutes in only three of 18 tMBSR teleconferences during the study, representing differences of 3–5 minutes each. Adaptations to content during tMBSR delivery were largely due to participant inability to complete yoga floor exercises due to balance or mobility limitations, including use of a wheelchair, which prevented participants from lying down or attaining a standing position from the floor. Similarly, participants who reported feeling unsteady while standing or who were fatigued or in a wheelchair remained seated during standing yoga, and were shown adapted postures for stretching and arm movements. The length of tMBSR home assignments were determined according to the audio recordings, with home practice expectations varying by type of practice assigned (body scan, 28 mins; sitting meditation, 30 mins; standing yoga, 33 mins; floor yoga, 41 mins), but actual time spent was not recorded.

Total class delivery time for tSupport was 540 minutes (9 hours, as planned) for all three intervention waves, and weekly and total course times were achieved as planned. Times for each activity were not specifically predetermined, and not measured. Delivery method and order of topics by week were achieved as planned.

Technical aspects of teleconference calls

Use of the toll-free teleconference phone system worked very well for participants. Only five of N=63 (8%) of randomized participants required staff support to complete calls; we verified for the n=8 who never attended a workshop or teleconference, that ability to use the teleconference system was not the reason for non-attendance. Four participants had limited home or mobile phone plans, and were subsequently loaned a mobile phone with paid minutes or a phone card for the 8 week course. One participant in tMBSR required assistance from staff to use the speakerphone. Participants were able to rejoin their call after brief interruptions, e.g. a participant calling from dialysis treatment had to hang up due to a procedure but later rejoined the call. The teleconference norms worked well over the 3 waves of the study and were not modified. Participants did not interrupt or speak over one another and when background noise made it difficult to hear, the instructor offered suggestions for increasing phone volume, or using the mute feature or discontinuing speakerphone in noisy environments.

The post-intervention questionnaire included an optional space for handwritten comments, which were overall positive and there were no overt criticisms related to the use of technology to complete calls. 41% of tMBSR participants provided a comment; of these, eight were positive and three were neutral. Examples of positive responses included, “I feel that [pain and stress] would have been worse without the skills I’ve learned,” “My health, especially my mental health, has improved during this study. I meditate first thing every morning and can’t imagine not doing it,” and “This class has change[d] me from the inside out. It has given me a deeper and fuller life.” One participant suggested that the class would have been even better if some participants had been more prepared, and another who was pleased overall suggested that he would have preferred an in-person class but that “teleconferencing was fine.” Two comments included specific and enthusiastic reference to the tMBSR teacher. Response rate for comments in the tSupport group was similar, with comments on 36% of questionnaires received, and of these, seven were positive, e.g. “I think that people [who] aren’t even sick could benefit from everything I learned,” and “I find that the skills learned make talking with people more enjoyable!” One comment reflected disappointment, “Most of this has been focused on communications, I was expecting something more clinical or medical.” Two neutral comments reflected the experience of participating in a group of similarly ill people, “It is somewhat sobering that all of the people in the group are dealing with kidney disease… the reality of it became more evident when meeting everyone for the first time.” Similarly to tMBSR, two participants in the tSupport group commented positively about the group facilitator.

DISCUSSION

The adaptations made to the standard MBSR curriculum are congruent with the recommendations of McCown et al. [28] and Dobkin et al. [57]. The format of MBSR was rearranged to allow for six of the eight weeks to be delivered by teleconference and the retreat was conducted in week 8 as a 5-hour workshop, yet the content from the formal template curriculum and the teaching intentions and axioms (intention, attention and attitude) were retained. Our tMBSR development team was highly experienced with MBSR, with populations who experience a wide range of abilities and disabilities, and with transplant patients. tMBSR was designed to leave “room” for participants to experience mindfulness. Although tMBSR was created for use with a kidney candidate population, no kidney-related content was added and the only kidney-specific consideration was in the selection of food provided to participants. The modified yoga DVD provided to tMBSR participants would be useful for people with limited mobility and a variety of conditions.

Our experience using a telephone-adapted delivery format for an MBSR program and an active control group was very positive. This multi-modal program offered participants an in-person workshop in week 1 to interact with each other and their group leader in-person, with an orientation to either meditation and yoga skills or a structured support program. Logistical information for participating in a conference call and questions were addressed before the calls commenced. The workshop in week 8 provided a retreat experience (tMBSR) or celebratory reunion (tSupport) in week 8. The telephone-adapted format reduced travel time and costs by 75%. The few technical difficulties encountered by participants were easily solved by the loan of a cell phone or a call from staff. Review of participant comments was largely positive and there were no complaints about course format or use of technology. Attendance at tMBSR in this trial was higher than for standard MBSR classes in a previous trial with solid organ (kidney, liver, heart or lung) recipients (n=71) where 75% attended at least 5 of 8 classes [17]. The ability to join the class by telephone makes it possible to receive an intervention while undergoing a treatment like dialysis, or from a remote location. High attendance and completion rates in Journeys support the utility of tMBSR as an accessible telephone-adapted intervention for people who are seriously and chronically ill, and will strengthen our planned comparisons of our telephone-adapted interventions to evaluate their efficacy for reducing symptom distress and improving health-related quality of life.

In the current study, treatment preference was much higher for tMBSR than for tSupport, but participants in tSupport did not have lower attendance and rated treatment satisfaction similarly to those in tMBSR, and group leader ratings of participant engagement were nearly identical for both groups. We interpret this as evidence that participants valued both interventions, even though their expectations were different. While alliance was not measured systematically, similar attendance rates and positive verbatims from participants and high ratings of engagement by group leaders, despite differences in treatment preference and expectations for future use, suggest that therapeutic alliance was strong in both groups. Expectation of benefit from techniques and information for coping with future health was significantly higher for tMBSR than tSupport at the end of the course, which points to the potential health management value of mindfulness training for kidney candidates and their willingness to participate. Future directions may include follow-up interviews to qualitatively explore the reasons why participants rated MBSR so highly and expected this course to be of greater benefit for managing their health than the support group.

The tMBSR program in Journeys is very similar to a telephone-adapted MBSR course delivered to telecommuting nurses in a corporate setting recently reported by Bazarko and colleagues, which consisted of two MBSR in-person group “retreat days” (weeks 1 and 8) and six 90-minute group teleconferences (weeks 2–7) [58]. For the N=41 nurses who participated in this nonrandomized study, average in-person “retreat” time was 13.9 hours (87%) and teleconference participation was high, mean = 7.9 of 9 hours (88%). Measures at baseline, post-intervention and 4-months post showed significant improvements in perceived stress, burnout, mental health, empathy and self-compassion.

Telephone-delivered programmed therapies are increasingly used for people with chronic illness to manage depression, anxiety and illness-specific symptoms. Meta-analysis of telephone delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (t-CBT) has shown favorable results for improving health outcomes [30] and has demonstrated non-inferiority with traditional CBT for clinician-rated and self-reported depression at post-treatment [31]. Mean attrition rates for teletherapies are far lower (9.5% in a meta-analysis of 8 CBT trials) [30] than the estimated 47% rate in face-to-face psychotherapy [59]. Teletherapies are more convenient for patients, with reduced travel time and more flexibility, moreover teletherapy sessions are often initiated by the therapist, which may bolster attendance rates [60]. Established telephone-delivered programmed therapies such as dialectical behavioral therapy (t-DBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (t-ACT) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (t-MBCT) combine mindfulness, acceptance, compassion, and values and relationships held by the patient with previously demonstrated behavioral approaches [61]. Successful delivery and effectiveness of t-CBT and preliminary feasibility results for telephone adapted mindfulness-infused therapies (t-DBT, t-ACT, t-MBCT) suggest distance delivery of MBSR could be useful across a wide spectrum of health and disability. Although tMBSR has promising outcomes in a corporate setting, Journeys will be the first randomized trial to determine its efficacy.

Limitations

The two telephone-adapted interventions have structural similarity but are not equal. The tMBSR course was more demanding of participants as in-person workshops and teleconference calls were longer and home assignment expectations were higher. Home assignments in the tSupport intervention were largely individually-generated and difficult to quantify but it is unlikely that tSupport participants spent 30–40 minutes per day on their home assignments. Despite the overall difference in class time, group interaction and instructor attention time were roughly equivalent between treatment arms, after removing silent meditation and yoga practice time from tMBSR. Careful review of fidelity checklists and notes revealed that the interventions were delivered as planned and without the need for ad hoc revisions. While we are confident that our courses were delivered as designed, one limitation of our treatment fidelity approach is that we did not audio-record each session for later verification[62], but relied on checklists, observation and frequent communications between our highly experienced group leaders and study staff. Similarly, participant engagement was rated by the leader of each intervention, and not by an independent rater, which may have resulted in bias. It may have been preferable to have participants indicate their intervention preference prior to randomization rather than recall it after the intervention.

Recommendations

Experience with tMBSR and tSupport generated several suggestions for future telephone-adapted group interventions. One potential solution for increasing attendance is to record teleconferences and provide a secure means of access to recordings for participants who are unable to join the calls at the scheduled time. Photographing the group leader and participants and provision of a printed or online visual directory of group members could be a useful tool, potentially allowing for recognizing people in larger groups on a conference call, and might foster group cohesion and communication, especially for people who do not easily remember names and faces. These options were not offered to Journeys participants as it was concluded that group leaders should be present during the first and last weeks of intervention delivery for safety and monitoring reasons, and due to issues of confidentiality of participants in this first trial of tMBSR for a population who are very ill. Our tMBSR teacher has suggested that teleconferences of up to 25 participants are possible. Those who are considering adapting traditional interventions with technology are encouraged to review the American Psychological Association’s Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology with consideration for informed consent, increased risks to confidentiality and security of data in for distance-delivered behavioral interventions [63].

CONCLUSIONS

tMBSR is a feasible intervention for kidney transplant candidates and can be expected to be acceptable to other persons with significant disabilities and high medical care demands. The primary requirement is sufficient capacity and hearing to use a standard telephone. tMBSR can be delivered safely, with fidelity and in a format that is more accessible and convenient to patients who have intensive treatment regimens. Our results indicate that kidney candidates preferred tMBSR over a telephone-adapted support intervention and had reasonable attendance rates and higher expectations that tMBSR would be of use for coping with their health in the future. tMBSR is an accessible and promising intervention. If trial results support efficacy, tMBSR may be useful over a wide spectrum of health to reduce distress, facilitate symptom management and improve wellbeing. [64]

Acknowledgement

“Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.”

Funding: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Award P01 DK013083 and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Award UL1TR000114

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsay SL, Lee YC, Lee YC. Effects of an adaptation training programme for patients with end-stage renal disease. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh S-CJ, Huang C-H, Chou H-C. Relationships among coping, comorbidity and stress in patients having haemodialysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(2):166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birmele B, Le Gall A, Sautenet B, Aguerre C, Camus V. Clinical, sociodemographic, and psychological correlates of health-related quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(1):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Eisele G, et al. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):658–666. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiegel BM, Melmed G, Robbins S, Esrailian E. Biomarkers and health-related quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1759–1768. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00820208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manley HJ, Cannella CA, Bailie GR, St Peter WL. Medication-related problems in ambulatory hemodialysis patients: a pooled analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):669–680. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ. The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14(1):82–99. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC, Lamprea-Montealegre J, Olufade T, Greer R, et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):953–973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2093–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2014. In: OPTN/SRTR. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmons RGKMS, Simmons RL. Gift of lIfe: the effect of organ transplantation on individual, family, and societal dynamics. 2 ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein FO, Arsenault KL, Taveras A, Awuah K, Finkelstein SH. Assessing and improving the health-related quality of life of patients with ESRD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(12):718–724. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuhara S, Lopes AA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Kurokawa K, Mapes DL, Akizawa T, et al. Health-related quality of life among dialysis patients on three continents: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 2003;64(5):1903–1910. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, N.Y: Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(3):373–386. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Russas V, Treesak C, Frazier PA, Hertz MI. Mindfulness meditation to reduce symptoms after organ transplant: A pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(3):58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Thomas W, Reilly-Spong M, Cramer-Bornemann M, Nyman JA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for solid organ transplant recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(5):30–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):613–622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson LE. Mindfulness-based interventions for physical conditions: a narrative review evaluating levels of evidence. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:651583. doi: 10.5402/2012/651583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garland SN, Carlson LE, Stephens AJ, Antle MC, Samuels C, Campbell TS. Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: a randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):449–457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Reilly-Spong M, Wall M, Winbush NY, Patterson R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction versus pharmacotherapy for chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Explore (NY) 2011;7(2):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong JC, Manber R, Segal Z, Xia Y, Shapiro S, Wyatt JK. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2014;37(9):1553–1563. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(6):537–559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubbling A, Reilly-Spong M, Kreitzer MJ, Gross CR. How mindfulness changed my sleep: focus groups with chronic insomnia patients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michael B, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden, Inc; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley D. Finding calm in the chaos: meditation. Prevention. 2006;58(11):158–161. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCown D, Reibel D, Micozzi MS. Teaching mindfulness - a practical guide for clinicians and educators. New York; London: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollon SD, Munoz RF, Barlow DH, Beardslee WR, Bell CC, Bernal G, et al. Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: promoting innovation and increasing access. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):610–630. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller I, Yardley L. Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(4):177–184. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohr DC, Ho J, Duffecy J, Reifler D, Sokol L, Burns MN, et al. Effect of telephone-administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2278–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohr DC, Siddique J, Ho J, Duffecy J, Jin L, Fokuo JK. Interest in behavioral and psychological treatments delivered face-to-face, by telephone, and by internet. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(1):89–98. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berzoff J, Swantkowski J, Cohen LM. Developing a renal supportive care team from the voices of patients, families, and palliative care staff. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(2):133–139. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop SR. What do we really know about mindfulness-based stress reduction? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(3):449–449. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horvath AO. The alliance in context: Accomplishments, challenges, and future directions. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2006;43(3):258–263. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yalom ID. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. 2d ed. New York: Basic Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Applebaum AJ, DuHamel KN, Winkel G, Rini C, Greene PB, Mosher CE, et al. Therapeutic alliance in telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):811–816. doi: 10.1037/a0027956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobkin PL. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: what processes are at work? Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackenzie MJ, Carlson LE, Munoz M, Speca M. A qualitative study of self-perceived effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in a psychosocial oncology setting. Stress and Health. 2007;23(1):59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans RL, Jaureguy BM. Group therapy by phone: a cognitive behavioral program for visually impaired elderly. Soc Work Health Care. 1981;7(2):79–90. doi: 10.1300/j010v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiener LS, Spencer ED, Davidson R, Fair C. National Telephone Support Groups - a new avenue toward psychosocial support for HIV-infected children and their families. Social Work with Groups. 1993;16(3):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Befort CA, Donnelly JE, Sullivan DK, Ellerbeck EF, Perri MG. Group versus individual phone-based obesity treatment for rural women. Eat Behav. 2010;11(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]