Abstract

Curcumin is a complementary therapy that may be helpful for the treatment of psoriasis due to its anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, antioxidant, and antiproliferative effects. In the present study we performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of a bioavailable oral curcumin in the treatment of psoriasis. Sixty-three patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis vulgaris (PASI < 10) were randomly divided into two groups treated with topical steroids and Meriva, a commercially available lecithin based delivery system of curcumin, at 2 g per day (arm 1), or with topical steroids alone (arm 2), both for 12 weeks. At the beginning (T0) and at the end of the therapy (T12), clinical assessment and immunoenzymatic analysis of the serum levels of IL-17 and IL-22 were performed. At T12, both groups achieved a significant reduction of PASI values that, however, was higher in patients treated with both topical steroids and oral curcumin than in patients treated only with topical steroids. Moreover, IL-22 serum levels were significantly reduced in patients treated with oral curcumin. In conclusion, curcumin was demonstrated to be effective as an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris and to significantly reduce serum levels of IL-22.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the skin, nails, and joints, which affects about 2% of the general population [1], with a significant impact on long-term quality of life [2]. The potential organ toxicity associated with chronically used systemic drugs, their immunosuppressive effects with the increased risk of infections and malignancies, and the high costs of some of them justify a novel assessment of therapeutic targets and modalities in patients with psoriasis [3, 4].

An estimated 80% of individuals in developing countries depend primarily on natural products to meet their healthcare needs, and recent surveys suggest that one in three Americans also uses medicinal natural products daily [5]. With regard to psoriasis, 51% of the patients use complementary and alternative medicine therapies to treat their skin, despite limited or no scientific data on the safety and efficacy of these treatments [6]. Among them, curcumin (dihydroferuloyl-methane, the active component of the Indian spice turmeric) has been used for centuries in traditional medicines of China and India [7], paving the way for the development of several studies both in cultured cells and in animal models, which revealed a surprisingly wide range of beneficial properties of this yellow-pigmented spice, including anticancer and anti-inflammatory activity [8–12]. Furthermore, the extremely good safety profile of curcumin represents the most compelling and key rationale for its use, as to date no studies have discovered any relevant toxic effects even at very high doses [13, 14]. Whereas curcumin has several molecular targets, it may be promising for the treatment of psoriasis interacting with the main pathogenetic pathways of the disease, namely, T cell-mediated inflammation via the inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) [15–17], keratinocyte proliferation, inhibiting phosphorylase kinase (PhK) [18–20], and angiogenesis [21–23].

The use of curcumin in the treatment of psoriasis is essentially based on anecdotal reports; however, few previous studies investigated its efficacy in psoriasis patients. In particular, Heng et al. [24] tested the effect of topical curcumin in 10 patients with psoriasis. Interestingly, topical curcumin was able to improve psoriasis lesions and to inhibit PhK activity, supporting the hypothesis that effective antipsoriatic activity may be achieved through the modulation of keratinocyte proliferation. In another study [25], the oral formulation of curcumin has been tested in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris, with a low overall response rate.

In this study, we used Meriva, a novel bioavailable lecithin based delivery form of curcumin [26] as an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis vulgaris. In particular, we compared the efficacy of topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% plus oral curcumin versus topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% plus oral matching placebo. Moreover, we investigated the effects of such a treatment on the serum levels of IL-17 and IL-22 that represent the prototypical cytokines secreted by T helper 17 (Th17) and T helper 22 (Th22) cells, respectively, and are thought to play a major role in the pathogenesis of the disease [27–33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Patients having mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis histologically confirmed with a Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) < 10 were included into the study. The exclusion criteria were the following: patients < 18 years old; patients with guttate, erythrodermic, or pustular psoriasis, as well as with psoriatic arthritis; patients who used systemic treatments for psoriasis within 3 months before day 0 or at any time during the study; patients who used topical treatments or phototherapy for psoriasis in the month before the study or at any time during the study; pregnant or lactating women, or women of childbearing age not using a reliable method of contraception; patients with clinically significant laboratory abnormalities at screening, or significant uncontrolled comorbidities. Enrolled participants were required to avoid prolonged exposure to sun or UV light and to discontinue nonmedicated emollients and medicated psoriasis shampoos 24 hours before each study visit. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the Hospital Ospedale Piero Palagi (Florence, Italy); all patients gave written informed consent.

2.2. Study Product

Patients were instructed to take 2 tablets 2 times a day, each tablet containing 500 mg Meriva (Indena SpA, Milan), for an overall daily dose of 2 g.

Meriva is a patented delivery form of the dietary phenolic curcumin, resorting to the use of lecithin (from non-GMO sources) to boost the absorption and bioavailability. The two ingredients form a noncovalent adduct in a 1 : 2 weight ratio, and two parts of microcrystalline cellulose are then added to improve flowability, with an overall content of curcumin of 20% (e.g., 100 mg for each tablet).

2.3. Study Design

This was a phase III, single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The study was performed at the Department of Surgery and Translational Medicine, Section of Dermatology (University of Florence, Italy), and consisted in a screening period, a baseline time in which PASI score was assessed and the patients started the treatment, a treatment period of 12 weeks, and a 4-week follow-up period. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% ointment (once daily on the lesions) plus 2 g per day of Meriva (2 tablets of 500 mg, twice daily) (arm 1) or topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% ointment (once daily on the lesions) plus matching placebo (2 tablets identical for size, form, and color from the verum, twice daily) (arm 2).

Patients were seen at a screening visit and then at baseline (T0) and weeks 4, 8, 12 (T12), and 16 (T16) for safety and efficacy evaluations. At T0 and at T12, serum samples were collected to investigate the levels of IL-17 and IL-22. The first participant was enrolled on May 3, 2012, and all study procedures were concluded on May 27, 2014.

2.4. Efficacy Endpoints

The primary objective of the study was to assess the superiority of topical methylprednisolone aceponate plus Meriva (arm 1) over topical methylprednisolone aceponate plus placebo (arm 2), evaluating the reduction of disease activity calculated by PASI (a composite evaluation instrument for psoriasis severity, with subscores for erythema, induration, scaling, and percentage of body-surface area affected) in both arms after 12 and 16 weeks from baseline. Secondary efficacy endpoints included PASI 50, PASI 75, PASI 90, and PASI 100 (reductions of 50%, 75%, 90%, and 100%, resp., in the baseline PASI score) that have been shown to represent a meaningful endpoint in psoriasis clinical trials [34]. Each endpoint was assessed by means of a between-group comparison of the proportion of patients who met the criterion for that objective.

2.5. Safety Endpoints

All patients who received at least one dose of study product were included in the safety analysis. Safety data were obtained by patient interview and the clinical examination conducted by the physician at all study visits.

2.6. Cytokine Analysis

Blood samples were collected from patients of both groups at baseline and T12 and were centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 ×g (5417R microcentrifuge; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Then, serum samples were subdivided into small aliquots to be stored at −80°C until tested for cytokine levels. Solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to determine IL-17 and IL-22 serum levels (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results are expressed in picogram per milliliter (pg/mL) as mean ± standard deviation. Samples and standards were analyzed in duplicate and only variation coefficients <15% were accepted.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of clinical efficacy of curcumin was performed with a Wilcoxon signed rank test between the pretreatment and posttreatment groups, and a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for comparing arm 1 with arm 2. The serological data of IL-17 and IL-22 were analyzed with Student's t-test. In order to verify the homogeneity of the two groups, we preliminarily compared clinical and serological parameters between the two pretreated series. Differences were considered as statistically significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

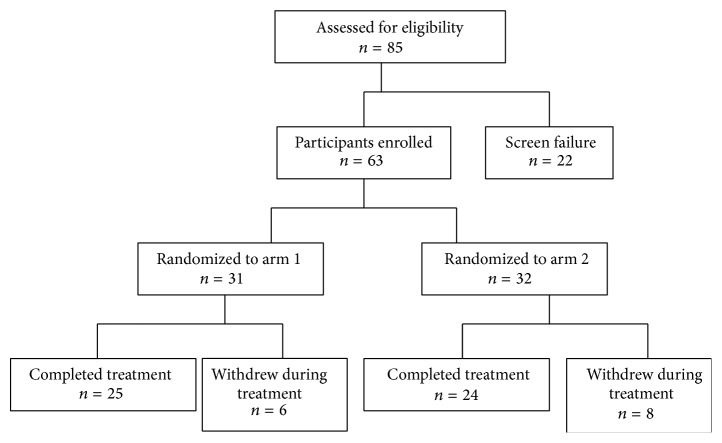

A total of 85 patients were screened, 63 of whom were enrolled and were randomized in one of the two arms (Figure 1). Of the 22 participants who were not included in the study, 4 were excluded because they had a PASI > 10, 9 had used topical treatments within 30 days before day 0, 5 had used systemic treatments within 3 months before day 0, and 4 had concurrent arthropathy. Baseline demographic information of the participants is reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic information of the participants.

| Arm 1 (n = 31) | Arm 2 (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 14 M, 17 F | 18 M, 14 F |

| Age (median, range) | 37 (19–62) | 41 (22–59) |

| Race | 30 Caucasian 1 Hispanic |

32 Caucasian |

| Onset age (median, range) | 31 (14–54) | 35 (20–51) |

Thirty-one patients were randomized into arm 1, while 32 into were randomized arm 2. Of the 31 patients enrolled into arm 1, 25 completed the trial up to week 16. Six out of 31 enrolled participants into arm 1 did not complete the trial. Two were withdrawn by the investigators before week 12 because of lack of efficacy and one for side effects (diarrhoea) and 3 were lost to follow-up.

Of the 32 patients into arm 2, 24 completed the trial up to week 16. Eight out of 32 enrolled participants did not complete the trial. Six were withdrawn by the investigators before week 12 because of lack of efficacy and/or worsening of their psoriasis and two for side effects (papular eruption on the face and nausea, resp.).

3.1. Efficacy Endpoints

Median PASI values [25th–75th percentile] at T0 were 5.6 [4.2–7.3] for arm 1 and 4.7 [3.8–5.8] for arm 2. At T12, both groups achieved a significant reduction of PASI values (arm 1: PASI at T12 = 1.3 [0.6–1.7], PASI T0 versus PASI T12: P < 0.05; arm 2: PASI at T12 = 2.4 [1.4–3.0], PASI T0 versus PASI T12: P < 0.05; Figure 2). However, the reduction of PASI values was higher in patients treated with both topical steroids and Meriva (arm 1) than in patients treated with topical steroids plus placebo (arm 2) (P < 0.05). The reduction of PASI remained significant for both groups at T16 (arm 1: PASI at T16 = 1.4 [1.2–1.8], PASI T0 versus PASI T16: P < 0.05; arm 2: PASI at T16 = 2.5 [1.8–3.3], PASI T0 versus PASI T16: P < 0.05; Figure 2). Moreover, at T16, patients included in arm 1 still had a more significant reduction in PASI values versus those included in arm 2 (P < 0.05; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Median PASI values [25°–75° percentile] at baseline (T0) and after 12 weeks (T12) in patients treated with topical methylprednisolone + Meriva (curcumin) or with topical methylprednisolone + placebo (placebo). ∗ P < 0.05.

Regarding the secondary efficacy endpoints, at T12, 23 patients in arm 1 (92%) and 13 in arm 2 (54%) achieved PASI 50, 12 patients in arm 1 (48%) and 3 in arm 2 (12%) achieved PASI 75, 5 patients in arm 1 (20%) and 1 in arm 2 (4%) achieved PASI 90, and 3 patients in arm 1 (12%) and 1 in arm 2 (4%) achieved PASI 100 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy secondary end points at T12 and at T16.

| T12 | T16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 | Arm 2 | Arm 1 | Arm 2 | |

| PASI 50 | 23/25 (92%) | 13/24 (54%) | 22/25 (88%) | 11/24 (46%) |

| PASI 75 | 12/25 (48%) | 3/24 (12%) | 11/25 (44%) | 2/24 (8%) |

| PASI 90 | 5/25 (20%) | 1/24 (4%) | 2/25 (8%) | 0/24 (0%) |

| PASI 100 | 3/25 (12%) | 1/24 (4%) | 1/25 (4%) | 0/24 (0%) |

At the follow-up visit four weeks after the completion of the therapy, at T16, 22 patients in arm 1 (88%) and 11 in arm 2 (46%) still maintained PASI 50, 11 patients in arm 1 (44%) and 2 in arm 2 (8%) maintained PASI 75, 2 patients in arm 1 (8%) and none in arm 2 maintained PASI 90, and 1 patient in arm 1 (4%) and none in arm 2 maintained PASI 100 (Table 2).

3.2. Safety End Points

Only one out of 31 patients who received the study product and 2 out of 32 patients receiving placebo reported one adverse event. The patient treated with Meriva complained of diarrhoea for two days and decided to discontinue the study protocol after 8 weeks; diarrhoea was also associated with fever as well as to other symptoms of viral gastroenteritis; however it was not possible to assess the exact aetiology neither to attribute the adverse effect to the study product.

As far as the two patients administered matching placebo, one complained of a papular eruption on the face occurring after 5 weeks of therapy that was attributed to the study product by the patient who decided to retire from the trial. The other one suffered of nausea that occurred after 3 weeks and persisted for two weeks until the discontinuation of the therapy.

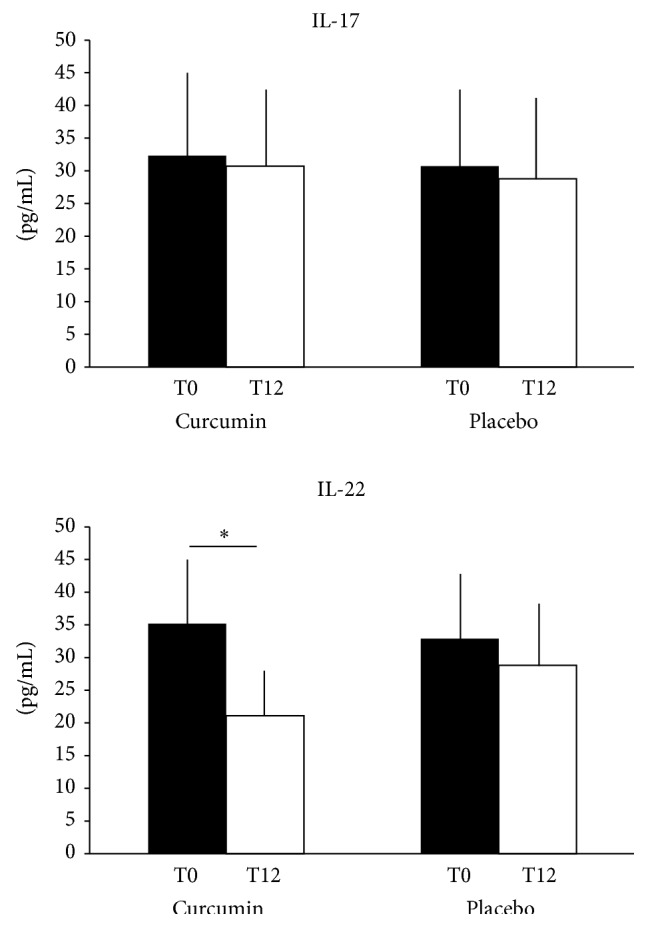

3.3. Serum Levels of Th17-Related Cytokines

IL-17 and IL-22 were detected in all the patients. At T0, both groups showed similar IL-17 levels, without significant differences (32.3 ± 13.6 in group 1 and 30.7 ± 12.2 in group 2, resp.; Figure 3). After the treatment, at T12, no significant changes in IL-17 serum concentrations can be observed in both groups (30.7 ± 10.9 in group 1 and 28.8 ± 12.9 in group 2, resp.; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

IL-17 and IL-22 mean values ± standard deviation at baseline (T0) and after 12 weeks (T12) in patients treated with topical methylprednisolone + Meriva (curcumin) or with topical methylprednisolone + placebo (placebo). Data are expressed as pg/mL. ∗ P < 0.05.

As for IL-17, IL-22 levels were similar in the two groups of patients with psoriasis at T0 (35.2 ± 9.5 in group 1 and 32.9 ± 11 in group 2, resp.; Figure 3). Interestingly, after 12 weeks, patients treated with topical methylprednisolone aceponate plus Meriva achieved a significant reduction of IL-22 serum levels (21.1 ± 7.5; IL-22 at T0 versus IL-22 at T12: P < 0.001), while the treatment with topical methylprednisolone aceponate plus placebo did not affect IL-22 expression (28.8 ± 10; Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The primary objective of our study was to investigate the efficacy of Meriva, a patented bioavailable formulation of curcumin, as an adjuvant therapy in patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis vulgaris (PASI < 10) that are using topical steroids.

Our data demonstrated that the combination of methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% ointment plus Meriva was superior to methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% ointment plus placebo in treating psoriasis. In fact, although both regimens were able to significantly affect psoriasis lesions, patients using both topical steroid and Meriva showed a reduction of PASI values that was significantly higher than that of patients using topical steroid plus placebo. Moreover, the group treated with topical steroid and oral bioavailable curcumin achieved best PASI 50, PASI 75, PASI 90, and PASI 100 scores than patients treated with topical steroid plus placebo, suggesting that oral curcumin might be a useful adjuvant treatment for patients with psoriasis.

Moreover, oral curcumin was well tolerated in our study. In fact, only one patient discontinued the therapy due to adverse effects, namely, diarrhea, which was more likely associated with a viral gastroenteritis rather than with the drug itself. Accordingly, other studies confirmed the safety of curcumin in human beings, even at high doses [14], being mild gastrointestinal upset the most common complaint.

Our results are partially in contrast with those from a previous study, where curcumin was used alone for the treatment of patients with psoriasis [25]. In that study, the authors tested 4.5 g per day of oral curcuminoid C3 complex in 12 patients with psoriasis, of which only 8 completed the treatment protocol, with an intention-to-treat response rate of 16.7% and an as-treated response rate of 25% (considering responders the patients that achieved an improvement of their skin lesions >50%, as assessed by physician global assessment). However, the limited efficacy of curcumin in such a study could be related to the low number of patients enrolled in the trial or to the low bioavailability of the used oral curcumin formulation, probably secondary to its extensive reduction and conjugation in the intestinal tract [35, 36], as stated by the authors.

By contrast, the formulation of curcumin used in our study through the lipidic matrix can capitalize on the rapid exchange of phospholipids between biological membranes and the extracellular fluids, shuttling phenolics into biological membranes and increasing their cellular absorption.

In fact curcumin, as other dietary phenolics, is sparingly soluble both in water and in oily solvents but shows polar groups that can interact with the polar heads of phospholipids [37].

As a result, curcumin combination with phospholipids according to the Phytosome technology, as applied in Meriva, showed a marked increase in the concentration of plasma curcuminoids after oral administration in healthy volunteers [38], improving the clinical benefits at dosages significantly lower than those associated with uncomplexed curcumin.

As previously reported, curcumin can be effective in treating psoriasis by affecting several pathogenetic pathways. Moreover, recent studies performed in autoimmune models suggest that curcumin can modulate T helper immune responses, downregulating the Th1 and Th17 cell pathways [39, 40]. Accordingly, such activities might operate even in psoriasis. In fact, in a mouse model of imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like inflammation, topical curcumin was demonstrated to improve the skin lesions with an effect comparable to that of clobetasol and to significantly decrease the cutaneous levels of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA [41].

Interestingly, we observed that only the treatment with topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% plus Meriva was able to significantly downregulate the concentrations of IL-22 in the serum of patients with psoriasis. As it is known, IL-22 is the prototypic cytokine secreted by Th22 cells, a subpopulation of T cells that selectively produces IL-22, but not IFN-γ nor IL-17. Several studies demonstrated that Th22 cells are increased in patients with psoriasis [28, 29, 42] and that IL-22 plays a major role in several steps of the pathogenesis of the disease, including inflammation and the proliferation of keratinocytes [43]. In fact, IL-22 induces keratinocytes to produce antimicrobial peptides, S100 acute-phase proteins, and chemokines (such as IL-8) and chemokine receptors, thus leading to neutrophilic chemotaxis within psoriasis lesions [44, 45]. Furthermore, IL-22 strongly induces hyperplasia of in vitro reconstituted human epidermis [45–47] and may be responsible for the acanthosis typically found in psoriasis. As a result, the effect on IL-22 and, therefore, on the Th22 pathway, may be included among the potential antipsoriatic activities of curcumin.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that Meriva, a novel lecithin based delivery form of curcumin, can be regarded as a safe and effective ingredient, useful for the adjuvant therapy of patients with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis vulgaris treated with topical steroids. Among the several biological effects of curcumin, the ability to downregulate T cell-mediated inflammation, and in particular the Th22 pathway, may be considered one of the major mechanisms by which the product can control psoriasis.

Conflict of Interests

The study was funded by a grant from Indena S.p.A., Milan, Italy.

References

- 1.Gelfand J. M., Weinstein R., Porter S. B., Neimann A. L., Berlin J. A., Margolis D. J. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Archives of Dermatology. 2005;141(12):1537–1541. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfand J. M., Feldman S. R., Stern R. S., Thomas J., Rolstad T., Margolis D. J. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a study from the US population. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;51(5):704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greaves M. W., Weinstein G. D. Treatment of psoriasis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(9):581–588. doi: 10.1056/nejm199503023320907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee P. K., Wahile A. Integrated approaches towards drug development from Ayurveda and other Indian system of medicines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;103(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischer A. B., Jr., Feldman S. R., Rapp S. R., Reboussin D. M., Lyn Exum M., Clark A. R. Alternative therapies commonly used within a population of patients with psoriasis. Cutis. 1996;58(3):216–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70(3):461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammon H. P. T., Wahl M. A. Pharmacology of Curcuma longa . Planta Medica. 1991;57(1):1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goel A., Kunnumakkara A. B., Aggarwal B. B. Curcumin as ‘Curecumin’: from kitchen to clinic. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;75(4):787–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein J., Sanderson I. R., MacDonald T. T. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent: the evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies. British Journal of Nutrition. 2010;103(11):1545–1557. doi: 10.1017/s0007114509993667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basnet P., Skalko-Basnet N. Curcumin: an anti-inflammatory molecule from a curry spice on the path to cancer treatment. Molecules. 2011;16(6):4567–4598. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S. C., Patchva S., Aggarwal B. B. Therapeutic roles of curcumin: lessons learned from clinical trials. The AAPS Journal. 2013;15(1):195–218. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanmugam M., Rane G., Kanchi M., et al. The multifaceted role of curcumin in cancer prevention and treatment. Molecules. 2015;20(2):2728–2769. doi: 10.3390/molecules20022728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankar T. N., Shantha N. V., Ramesh H. P., Murthy I. A., Murthy V. S. Toxicity studies on turmeric (Curcuma longa): acute toxicity studies in rats, guinea pigs & monkeys. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1980;18(1):73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lao C. D., Ruffin M. T., IV, Normolle D., et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006;6, article 10 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S., Aggarwal B. B. Activation of transcription factor NF-κ B is suppressed by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(42):24995–25000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S. C., Tyagi A. K., Deshmukh-Taskar P., Hinojosa M., Prasad S., Aggarwal B. B. Downregulation of tumor necrosis factor and other proinflammatory biomarkers by polyphenols. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2014;559:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aggarwal B. B., Gupta S. C., Sung B. Curcumin: An orally bioavailable blocker of TNF and other pro-inflammatory biomarkers. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;169(8):1672–1692. doi: 10.1111/bph.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy S., Aggarwal B. B. Curcumin is a non-competitive and selective inhibitor of phosphorylase kinase. FEBS Letters. 1994;341(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H.-B., Song W., Chen L.-Y., et al. Differential expression and regulation of prohibitin during curcumin-induced apoptosis of immortalized human epidermal HaCaT cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2014;33(3):507–514. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balasubramanian S., Eckert R. L. Keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis—differential mechanisms of regulation by curcumin, EGCG and apigenin. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224(3):214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilken R., Veena M. S., Wang M. B., Srivatsan E. S. Curcumin: a review of anti-cancer properties and therapeutic activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Molecular Cancer. 2011;10, article 12 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vyas D., Gupt S., Dixit V., Anita K., Kaur S. To study the effect of curcumin on the growth properties of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology—Animal. 2015;51(5):488–494. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9852-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar D., Kumar M., Saravanan C., Singh S. K. Curcumin: a potential candidate for matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2012;16(10):959–972. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.710603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heng M. C. Y., Song M. K., Harker J., Heng M. K. Drug-induced suppression of phosphorylase kinase activity correlates with resolution of psoriasis as assessed by clinical, histological and immunohistochemical parameters. British Journal of Dermatology. 2000;143(5):937–949. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurd S. K., Smith N., VanVoorhees A., et al. Oral curcumin in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris: a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;58(4):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuomo J., Appendino G., Dern A. S., et al. Comparative absorption of a standardized curcuminoid mixture and its lecithin formulation. Journal of Natural Products. 2011;74(4):664–669. doi: 10.1021/np1007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowes M. A., Suárez-Fariñas M., Krueger J. G. Immunology of psoriasis. Annual Review of Immunology. 2014;32:227–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalak-Stoma A., Bartosińska J., Kowal M., Juszkiewicz-Borowiec M., Gerkowicz A., Chodorowska G. Serum levels of selected Th17 and Th22 cytokines in psoriatic patients. Disease Markers. 2013;35(6):625–631. doi: 10.1155/2013/856056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benham H., Norris P., Goodall J., et al. Th17 and Th22 cells in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2013;15(5, article R136) doi: 10.1186/ar4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosmi L., de Palma R., Santarlasci V., et al. Human interleukin 17-producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(8):1903–1916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caproni M., Antiga E., Melani L., Volpi W., del Bianco E., Fabbri P. Serum levels of IL-17 and IL-22 are reduced by etanercept, but not by acitretin, in patients with psoriasis: a randomized-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2009;29(2):210–214. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antiga E., Volpi W., Chiarini C., et al. The role of etanercept on the expression of markers of T helper 17 cells and their precursors in skin lesions of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2010;23(3):767–774. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antiga E., Volpi W., Cardilicchia E., et al. Etanercept downregulates the Th17 pathway and decreases the IL-17+/IL-10+ cell ratio in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2012;32(6):1221–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlin C. S., Feldman S. R., Krueger J. G., Menter A., Krueger G. G. A 50% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 50) is a clinically significant endpoint in the assessment of psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;50(6):859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant K. L., Schneider C. D. Turmeric. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2000;57(12):1121–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ireson C. R., Jones D. J. L., Orr S., et al. Metabolism of the cancer chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat intestine. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2002;11(1):105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidd P. M. Bioavailability and activity of phytosome complexes from botanical polyphenols: the silymarin, curcumin, green tea, and grape seed extracts. Alternative Medicine Review. 2009;14(3):226–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marczylo T. H., Verschoyle R. D., Cooke D. N., Morazzoni P., Steward W. P., Gescher A. J. Comparison of systemic availability of curcumin with that of curcumin formulated with phosphatidylcholine. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2007;60(2):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanakasabai S., Casalini E., Walline C. C., Mo C., Chearwae W., Bright J. J. Differential regulation of CD4+ T helper cell responses by curcumin in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2012;23(11):1498–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park M.-J., Moon S.-J., Lee S.-H., et al. Curcumin attenuates acute graft-versus-host disease severity via in vivo regulations on Th1, Th17 and regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067171.e67171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun J., Zhao Y., Hu J. Curcumin inhibits imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like inflammation by inhibiting IL-1beta and IL-6 production in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067078.e67078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan L., Ding Y., Han S., Zhang Z., Liu X. An increased proportion of circulating Th22 and Tc22 cells in psoriasis. Cellular Immunology. 2014;290(2):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng Y., Danilenko D. M., Valdez P., et al. Interleukin-22, a TH17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445(7128):648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kao C.-Y., Chen Y., Thai P., et al. IL-17 markedly up-regulates beta-defensin-2 expression in human airway epithelium via JAK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):3482–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boniface K., Bernard F.-X., Garcia M., Gurney A. L., Lecron J.-C., Morel F. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(6):3695–3702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolk K., Kunz S., Witte E., Friedrich M., Asadullah K., Sabat R. IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity. 2004;21(2):241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eyerich S., Eyerich K., Pennino D., et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(12):3573–3585. doi: 10.1172/jci40202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]