Abstract

Mutations in the dysferlin gene (DYSF) lead to human muscular dystrophies known as dysferlinopathies. The dysferlin-deficient A/J mouse develops a mild myopathy after 6 months of age, and when younger models the subclinical phase of the human disease. We subjected the tibialis anterior muscle of 3- to 4-month-old A/J mice to in vivo large-strain injury (LSI) from lengthening contractions and studied the progression of torque loss, myofiber damage, and inflammation afterward. We report that myofiber damage in A/J mice occurs before inflammatory cell infiltration. Peak edema and inflammation, monitored by magnetic resonance imaging and by immunofluorescence labeling of neutrophils and macrophages, respectively, develop 24 to 72 hours after LSI, well after the appearance of damaged myofibers. Cytokine profiles 72 hours after injury are consistent with extensive macrophage infiltration. Dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ mice show much less myofiber damage and inflammation and lesser cytokine levels after LSI than do A/J mice. Partial suppression of macrophage infiltration by systemic administration of clodronate-incorporated liposomes fails to suppress LSI-induced damage or to accelerate torque recovery in A/J mice. The findings from our studies suggest that, although macrophage infiltration is prominent in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle after LSI, it is the consequence and not the cause of progressive myofiber damage.

The dysferlin gene (DYSF; Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man no. *603009, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim) encodes dysferlin, a tail-anchored, integral membrane protein of 230 kDa that is thought to mediate membrane stability or fusion through the action of calcium-binding C2 domains in its large cytoplasmic region. Mutations in dysferlin have been linked to muscle diseases in humans, including limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B (LGMD2B), Miyoshi myopathy (MMD), and distal myopathy with anterior tibial onset (DMAT) (Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man nos. 253601, 254130, and 606768, respectively, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). Dysferlinopathies are characterized by their onset in the late teen years, followed by rapid progression and wheelchair dependence for mobility by 40 years of age, but they are typically not fatal, due to sparing of the diaphragm and cardiac muscle. Clinical management involves maintaining mobility, functional independence, and general health through therapeutic exercise, training in activities of daily living, the use of orthoses and assistive technology, and pharmacological management of medical issues that may or may not be linked to the muscle pathology. Potential treatments of dysferlinopathies are under intensive study and include the use of adeno-associated virus encoding fragments of the protein1–3; exon-skipping strategies4; up-regulation of dysferlin-like molecules in muscle, such as myoferlin2; small molecules that moderate the phenotype of dysferlinopathic muscle5; and manipulation of the immune and complement systems.6,7

Since muscle biopsies from patients with dysferlinopathies and muscle samples from some murine models of dysferlinopathy show increased inflammatory cell infiltration, the role of inflammation in dysferlinopathies has received considerable attention.6–11 Monocytes lacking dysferlin demonstrate increased phagocytic activity,9 and knocking out complement C3 or myeloid differentiation primary response 88 protein in dysferlin-null mice reduces the severity of dystrophic features.6,7 Clinically, many patients are misdiagnosed as having an inflammatory myopathy, specifically polymyositis, due to the prominence of interstitial infiltration by macrophages.12,13 However, unlike autoimmune myositis, the human leukocyte antigen–class I complex is not overexpressed in dysferlinopathies.14

Here we employ a previously validated in vivo muscle-injury model that uses repeated large-strain lengthening contractions of the hind limb ankle dorsiflexor muscles (large-strain injury; LSI) to investigate the contribution of inflammation to structural and functional damage in dysferlinopathic muscle following exercise-induced injury.2,15–18 Findings from our earlier studies showed that myofiber damage and macrophage infiltration 3 days after LSI are common features among several dysferlinopathic strains of mice, albeit at different levels, and that the A/J strain of dysferlinopathic mice, with a slowly progressing, moderately dystrophic phenotype during early life, models the preclinical stage of dysferlinopathies in humans.18 At 3 to 4 months of age, the A/J mouse does not show compromised muscle strength and shows only very mild histological changes compared with those in other dysferlin-deficient strains.18–20

Here, we examine more closely the effects of LSI on the dysferlin-deficient A/J mouse to compare the progression of myofiber damage in the period after injury to that of inflammation and to learn whether inflammatory cell infiltration is a cause or consequence of myofiber necrosis. We hypothesized that inflammatory cell infiltration contributes to myofiber necrosis after initial injury and that inhibiting inflammatory cell infiltration would significantly improve the rate of recovery. Our results show, however, that inflammation follows myofiber damage in A/J muscle subjected to LSI and that suppressing inflammation does not reduce myofiber damage or promote better functional recovery. Our results also indicate that, although inflammation is prominent in dysferlinopathies, it is up-regulated in response to myofiber damage, suggesting that inflammatory cell infiltration is a consequence and not a primary cause of myofiber damage in these diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animal Subjects

Dysferlin-deficient A/J mice (stock no. 000646) and the closely related dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ mice (stock no. 000647) were either obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or bred from pairs purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All were male, 14 to 18 weeks of age. Our protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD).

Torque Measurements and Contraction-Induced Muscle Injury

Measurements of contractile torque and LSI of the anterior compartment ankle dorsiflexor muscles [tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus] were performed in vivo as described, with the Small-Animal Unit for Muscle Injury, Muscle Testing, and Muscle Training System (University of Maryland).15,17 Torque measurements and lengthening contractions were performed with the mice under general anesthesia induced and maintained by an isoflurane vaporizer (VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA).

Each animal was assigned a unique identification number and assessed for the maximal isometric tetanic torque of its left ankle dorsiflexors. After baseline torque was measured, 20 lengthening (eccentric) contractions were performed by the dorsiflexors at 1 contraction/minute, through an arc of 90 to 180 degrees of plantar flexion, as described.15,17 After this LSI and 3 minutes of rest, we measured maximal isometric torque again. We studied four animals of each strain longitudinally to assess changes in contractile torque after LSI. We designated another three animals from each strain for torque measurements and tissue collection at approximately 10 minutes and 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours after LSI. We combined the torque data from animals studied longitudinally and terminally to yield a sample size of n = 7 animals per time point.

Noninvasive Monitoring of Injury by T2-Weighted MR Imaging

T2-weighted rapid-acquisition relaxation-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) images (TE1/TE2/TR/ETL/NEX 1/4 17.4 ms/52.1 ms/5000 ms/4/8) of the hind limbs of the mice were acquired on a 7-T MR system (BioSpec 7T/30; BioSpin scanner; Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA), as described.15,21 We used a 1H surface coil array as the receiver and a 72-mm linear-volume coil as the transmitter (Bruker). Anesthetized mice were placed supine on a custom-designed body holder to align the two legs parallel to the static magnetic field. Four animals of each strain were studied longitudinally at approximately 30 minutes, 6 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, 7 days, and 14 days after lengthening contractions to monitor changes in the injured (left) and uninjured (right) TA muscles. High-resolution images of radial sections were captured at 0.5-mm intervals along the length of the TA muscle (32 slices). Images were opened as an image sequence in ImageJ software version 1.43u (NIH, Bethesda, MD), and the images obtained at the approximate midbelly of the left and right TA muscles (where the tibia appeared as a crescent) were saved as .tif files. The images were analyzed using Volocity imaging software version 6.3 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The boundaries of the left and right TA muscles were defined, and the mean pixel intensity (MPI) of the enclosed area was obtained. The MPI in a fixed rectangular area placed over the plantar flexors was used to correct for background noise. The change in signal intensity in the injured TA muscle was calculated as:

| (1) |

The T2-weighted MR signal correlates with the level of edema in the muscle and is commonly used for assessing the severity of injury in a clinical setting.22,23 Recently, T2-weighted MR imaging has been used for detecting spontaneous or exercise-induced muscle damage in dystrophic murine muscle.24

Histological Studies

To assess the general morphology of the TA and to visualize cellular infiltrates and myofiber damage, we performed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, as described.17,25 We stained 8-μm cross sections of unfixed, snap-frozen TA muscle with Harris modified hematoxylin (HHS 16; Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO) and aqueous eosin-Y (HT110216; Sigma-Aldrich) and observed the sections under a light microscope (Zeiss Axioskop, ×20 objective; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). We studied 9 or 10 unique visual fields per muscle in three muscles per time point (uninjured, at approximately 10 minutes, 3 hours, 6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours). We then combined the numbers of damaged fibers from each of the fields to yield a sample size of n = 27 to 30 fields per time point.

To detect myofibers that had sustained sarcolemmal damage after LSI, we labeled 10-μm frozen cross sections of the TA muscle with goat anti-mouse antibodies to IgG (heavy and light chains) conjugated to Alexa 568 dye (A-11004; Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). This assay is based on the principle that large serum molecules, such as IgG, are excluded from myofibers with intact sarcolemmal membranes, but enter into the myoplasm of myofibers that have sustained sarcolemmal damage.26 We costained sections with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Alexa 488 dye (W11261; Life Technologies) to mark myofiber boundaries and with DAPI (71-03-01; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) to label nuclei. Sections were collected onto slides (15-188-48; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), fixed for 10 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and labeled as described earlier except that primary antibodies were omitted.18,25 We sectioned and labeled two muscles per time point and studied six visual fields per muscle (Zeiss Axioskop, ×20 objective; Carl Zeiss). We then combined the numbers of mouse IgG-positive (Ms-IgG+) fibers from each of the fields to yield a sample size of n = 12 fields per time point.

Neutrophils and macrophages were immunolabeled with rat anti-mouse antibodies to Ly6G (neutrophil marker, MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) and CD68 (macrophage marker, MCA1957; AbD Serotec), as described, with minor modifications.18,25 Briefly, 16-μm cross sections were labeled with either of these antibodies in addition to antibodies to dystrophin to mark the boundaries of myofibers and with DAPI to label nuclei. Slides were subsequently incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rat secondary antibodies (A10517; Life Technologies), which were in turn labeled with streptavidin conjugated to Alexa 568 dye (S-11226; Life Technologies). Labeled sections were studied under confocal optics (Zeiss LSM510 DUO, ×40 objective; Carl Zeiss), and four digital images of nonoverlapping fields were obtained for quantitative analyses. To convert the number of cells per visual field to cells per square millimeter, raw counts of cells were multiplied by a conversion factor of 19.75 based on calculations performed with Volocity imaging software version 6.3 (PerkinElmer). We combined the numbers of neutrophils or macrophages from each field to yield a sample size of n = 12 fields per time point for each cell type.

Cytokine and Chemokine Profiling

Injured and uninjured TA muscle collected from A/WySnJ and A/J mice 72 hours after LSI were profiled for 11 cytokines or chemokines that mediate inflammation. Cytokine levels were assessed in muscle homogenates with a multiplex assay kit (MCYTOMAG-70K, Milliplex MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Homogenates of unfixed, freshly harvested TA muscle were prepared on ice with a sample-grinding kit (80-6483-37; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA), with half the volume of buffer recommended by the manufacturer to optimize the concentration of the cytokines/chemokines.27 The homogenates were subjected to centrifugation at 15,996 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C (5415 C centrifuge; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The supernatants were stored as aliquots at −80°C until analysis. Data were collected from three A/WySnJ and A/J mice, yielding a sample size of n = 3 per strain per time point. The cytokines and chemokines that were profiled were eotaxin, Il-13, Il-1A, Il-1B, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, monokine induced by γ-interferon, macrophage inflammatory protein 1A and 1B, Rantes (regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted), and vascular endothelial growth factor. These cytokines and chemokines were chosen because only they yielded readable levels in pilot experiments that were performed as a 32-plex assay, which also included granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, γ-interferon, Il-10, Il-12 P40, Il-12 P70, Il-15, Il-17, Il-2, Il-3, Il-4, Il-5, Il-6, Il-7, Il-9, Ip-10, leukemia inhibitory factor, Lix (recombinant mouse Cxcl-5), macrophage inflammatory protein 2, and tumor necrosis factor. The assays were performed in the Cytokine Core Laboratory, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Macrophage Depletion by Clodronate-Incorporated Liposomes

We used liposomes loaded with clodronate (dichloromethylenediphosphonic acid disodium salt; a gift from Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) to deplete circulating monocytes (macrophage precursors) in mice subjected to LSI. Liposomes loaded with clodronate28 were purchased from ClodronateLiposomes.com (Haarlem, the Netherlands). As we observed that macrophage infiltration increased steeply between 24 and 48 hours after LSI in A/J muscle and increased further from 48 to 72 hours, we injected animals with 15 μL/g body weight of clodronate-incorporated liposomes 24 hours after LSI. This dose was chosen based on our own pilot data and earlier protocols for reducing macrophage infiltration into muscle.29,30 We injected the same volume of phosphate-buffered saline as control.

Age-matched animals were assigned to either the experimental group or the control group (n = 5 per group). Torque measurements and LSI were performed before and after LSI, and again at 72 hours after LSI. Injured and uninjured TA muscle was then collected without fixation, briefly immersed in mineral oil, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Frozen TA muscle was sectioned and stained with H&E or labeled with antibodies to macrophages, described in Histological Studies. Damaged fibers, identified by their pale and disrupted cytoplasm, were counted from digital images of 12 nonoverlapping visual fields for each uninjured and injured TA muscle (Zeiss Axioskop, ×20 objective; Carl Zeiss). Macrophages, identified by positive labeling for CD68 around a nucleus labeled with DAPI, were counted from digital images from eight nonoverlapping visual fields of each uninjured and injured TA muscle. The percentages of damaged fibers in each visual field and the number of macrophages per square millimeter in each animal were used for statistical analyses.

Flow Cytometry on Mononuclear Cells Isolated from Muscle

We performed flow cytometry on mononuclear cells isolated from TA muscle by adapting established methods that have been used to isolate myogenic progenitor cells.31 As our pilot data with myotoxin injury showed that a single TA muscle only yields a few cells, we pooled four TA muscles together and performed the experiment in duplicate (n = 2 data points per marker) to obtain cell numbers ample for quantitative analysis. We used antibodies to CD45 (leukocyte marker), myoD (myoblast marker), and ER/TR7 (fibroblast marker), as well as antibodies to Ly6G (neutrophil marker) and CD68 (macrophage marker).

Statistical Analysis

Torque data were analyzed by a 2-way analysis of variance; T2-weighted MR signal intensity data by a 2-way repeated-measures analysis of variance; and damaged fibers, Ms-IgG+ fibers, and inflammatory cell counts by Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance on ranks. The Student-Newman-Keuls method was used for making pairwise comparisons of data sets that contained equal sample sizes (all sets other than damaged fiber counts), and the Dunn method was used for data sets of unequal sizes. All data are shown as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered as significant. Linear regression analyses were performed to determine whether the number of damaged myofibers at a given time point correlated better with neutrophil numbers or macrophage numbers, and also to assess whether the number of damaged myofibers at a previous time point was a better predictor of macrophage numbers, or whether the number of macrophages at a previous time point was a better predictor of the number of damaged myofibers. All statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat software version 3.5 (Systat Software, Chicago, IL).

Results

We studied dysferlin-deficient and control mice to: i) assess several features of the TA muscle after LSI, including the loss and recovery of torque, tissue edema, and histological changes at different time points after injury, ii) identify cells that infiltrate muscle after injury, and iii) learn if inhibiting macrophage infiltration enables better functional recovery after LSI.

Loss and Recovery of Contractile Torque after LSI

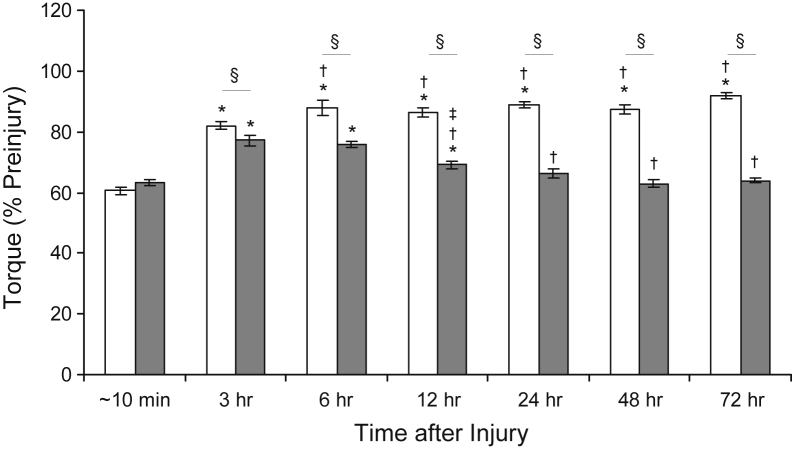

Immediately (approximately 10 minutes) after LSI, both control muscle and dysferlin-deficient muscle lost similar levels of contractile torque (Figure 1). At 3 hours after LSI, torque values in both control muscle and dysferlin-deficient muscle recovered partially (Figure 1). At 6 hours after LSI, control muscle showed a significant increase in torque compared with that at 3 hours, but dysferlin-deficient muscle did not (Figure 1). At 12 hours and beyond, torque values in control muscle remained at levels greater than those at 3 hours, approaching preinjury values (Figure 1). By contrast, at 12 hours, torque declined in dysferlin-deficient muscle to levels less than those at 3 and 6 hours, although torque was still greater than immediately after LSI (Figure 1). By 24 hours after LSI, torque levels in dysferlin-deficient muscle were as low as those produced immediately after LSI, and they stayed low up to 72 hours. These results indicate that dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle recovers partially after LSI over 3 hours but then relinquishes this gain over the following day, whereas control muscle largely recovers function within 24 hours after LSI.

Figure 1.

Loss and recovery of contractile torque after large-strain injury. The data indicate that dysferlin-deficient muscle is not more susceptible to initial injury compared with dysferlin-sufficient muscle. Partial recovery occurs over 3 to 6 hours in both dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ and dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle, after which A/J muscle (gray bars) loses contractile torque whereas A/WySnJ muscle (white bars) continues to recover. ∗P < 0.05 versus approximately 10 minutes; †P < 0.05 versus 3 hours; ‡P < 0.05 versus preceding time point other than approximately 10 minutes or 3 hours; and §P < 0.05 between strains.

Noninvasive Monitoring of Injury by T2-Weighted MR Imaging

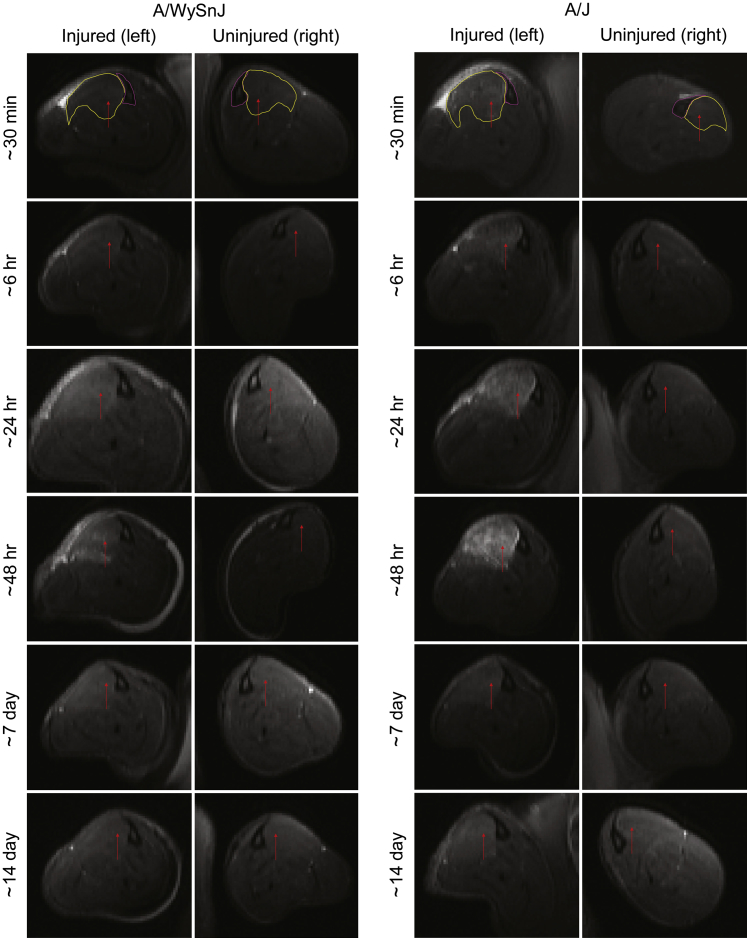

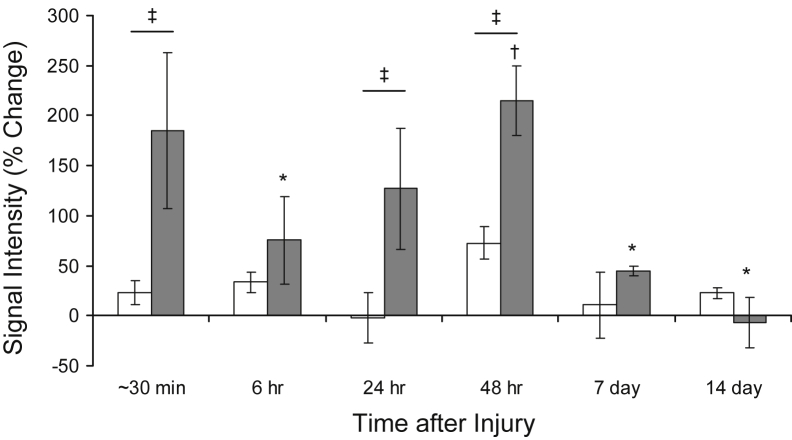

To ascertain the early changes in the TA muscle after LSI, we performed in vivo T2-weighted MR imaging. Representative MR images obtained over time from the same control or dysferlin-deficient mouse suggest that edema in the TA muscle is minimal in control muscle at all time points after LSI, but it is pronounced in dysferlin-deficient muscle soon after LSI and again 48 hours later (Figure 2). Quantitative analyses of MR images, such as those shown in Figure 2, indicate that shortly (approximately 30 minutes) after LSI, there was an approximately 25% increase in T2 signal intensity in control muscles and an approximately 175% increase in dysferlin-deficient muscle (Figure 3). In control muscle, the T2 signal did not change significantly at later times. In dysferlin-deficient muscle, by contrast, the intensity of the T2 signal decreased between approximately 30 minutes and 6 hours to levels similar to those in controls; thereafter, the T2 signal increased beyond hour-6 levels (Figure 3). Thus, similar to the partial recovery of contractile torque in dysferlin-deficient muscle at 3 and 6 hours after LSI, muscle edema initially resolved between approximately 30 minutes and 6 hours and then increased again thereafter. At 7 and 14 days after injury, the T2 signal in A/J muscle was low, in agreement with our earlier data that the damage from LSI begins to resolve beyond 3 days after injury.17

Figure 2.

T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images showing the progression of injury over time. T2-weighted MR imaging of the hind limbs of the same dysferlin-deficient A/J mouse and dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ mouse studied longitudinally after injury shows that muscle damage progresses over several days in A/J muscle. An increased T2 signal after injury, which corresponds to increased edema, can be appreciated by an increase in the whiteness of the muscle. The tibia and the tibialis anterior muscle of the injured (left) and uninjured (right) hind limbs are encircled in pink and yellow, respectively, in the uppermost panels. Arrows indicate tibialis anterior muscle in all panels.

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. Data obtained from images of tibialis anterior muscle such as those shown in Figure 2, analyzed as described in Materials and Methods, show that injured dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle (gray bars) has a greater T2 signal than does injured dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ muscle (white bars) soon after large-strain injury. At 6 hours after injury, the T2 signal intensity is decreased in A/J muscle and is statistically indistinguishable from that in A/WySnJ muscle. At 24 and 48 hours, however, the signal in A/J muscle is significantly greater than that in A/WySnJ muscle. By 7 and 14 days after injury, the T2 signal is decreased in A/J muscle, suggesting that edema resolves by this time. ∗P < 0.05 versus approximately 30 minutes; †P < 0.05 versus 6 hours; and ‡P < 0.05 between strains.

Histological Studies of the TA Muscle after LSI

We next performed histological studies to assess the progression of myofiber damage, sarcolemmal damage, and inflammatory cell infiltration.

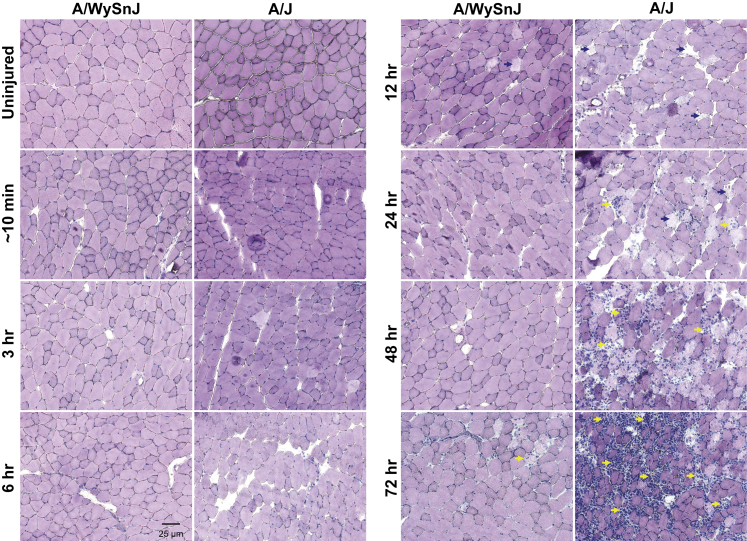

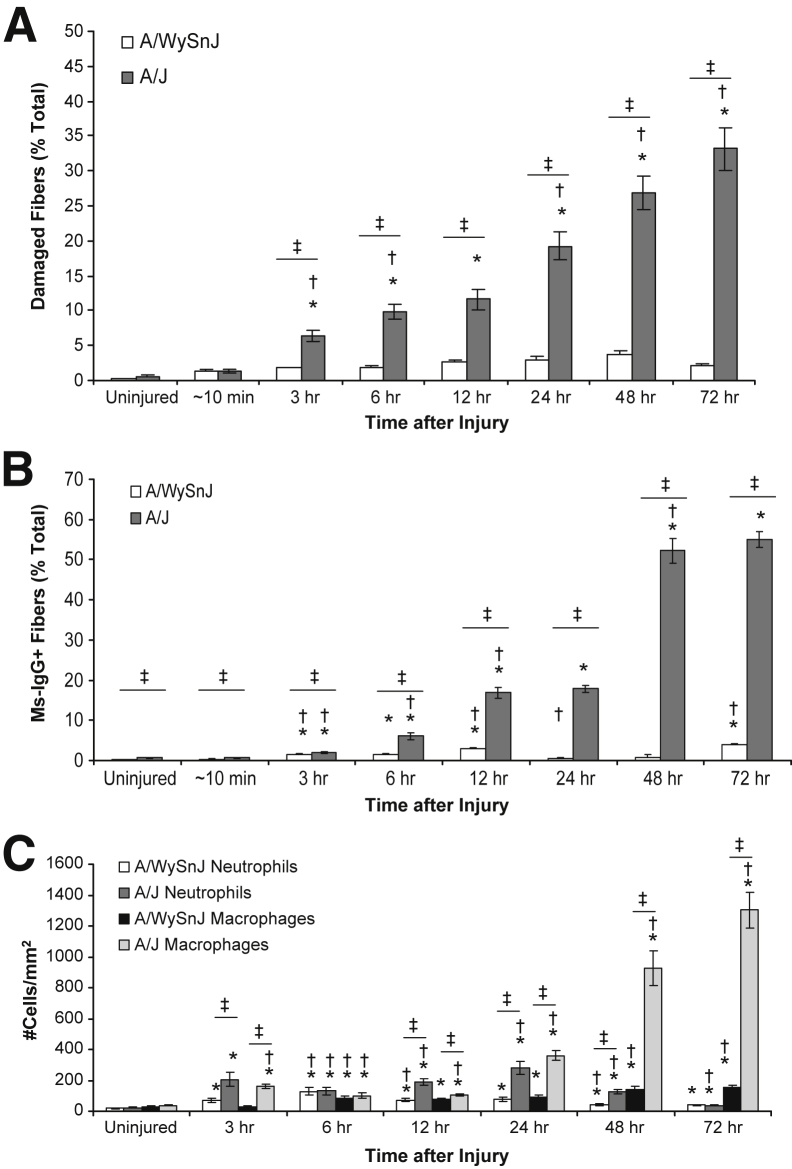

H&E staining of TA muscle sections suggested that myofiber damage at all time points after LSI was minimal in control muscle but that, in dysferlin-deficient muscle, damaged fibers increased in number slowly after LSI as a function of time (Figure 4). H&E staining also revealed that the infiltration of mononuclear cells progressively increased at 48 and 72 hours after LSI, when they occupied areas of damaged myofibers (Figure 4). Quantitative analyses of H&E-stained sections (Figure 5A) indicated that, in dysferlin-sufficient muscle, fiber damage was low but there was an initial increase in damaged fibers between 12 and 24 hours, followed by a further increase between 24 and 48 hours.

Figure 4.

Progression of myofiber damage and mononuclear cell infiltration after injury. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tibialis anterior muscle cross sections reveals that after injury, damaged fibers (blue arrows) appear over several hours and days in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle. Over time, as myofiber damage becomes more widespread, damaged areas are infiltrated by mononuclear cells (yellow arrows). Myofiber damage and cellular infiltration are low in dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ muscle.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analyses of damaged fibers, sarcolemmal damage, and infiltration by neutrophils and macrophages after injury. Images such as those in Figures 4, 6, and 7 were analyzed quantitatively, as described in Materials and Methods. A: After injury, myofiber damage slowly increases in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle over several hours and days, with a sharp increase occurring between 12 and 24 hours and a further increase over 24 to 48 hours after injury. Myofiber damage in dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ muscle is minimal. B: After injury, the number of mouse IgG-positive (Ms-IgG+) fibers, a measure of sarcolemmal damage, increases over several hours and days in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle. An increase of roughly 2.5-fold in Ms-IgG+ fibers occurs between 6 and 12 hours and then again between 24 and 48 hours after injury. Compared with A/J muscle, very few A/WySnJ myofibers become permeable to Ms-IgG after injury. C: Low levels of neutrophil infiltration are seen at early time points in both A/WySnJ and A/J muscle, with the latter being significantly greater. Macrophage infiltration is low in A/WySnJ muscle, but greater in A/J muscle, with a sharp increase occurring between 24 and 48 hours and a further increase occurring between 48 and 72 hours. ∗P < 0.05 versus uninjured; †P < 0.05 versus preceding time point other than uninjured; and ‡P < 0.05 between strains.

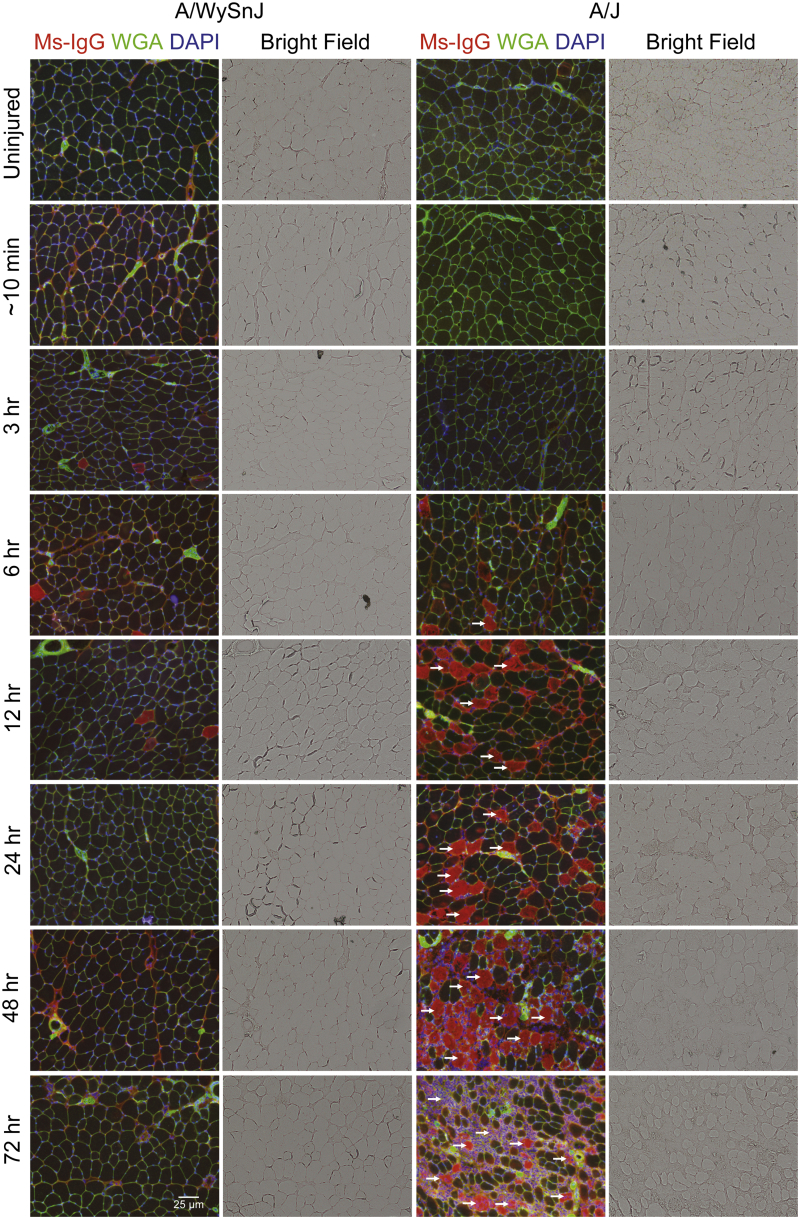

As the entry of large serum molecules such as IgG into myofibers is indicative of sarcolemmal damage,26 we studied the appearance of Ms-IgG+ fibers over time after injury (Figures 5B and 6). Similar to the trend seen with the appearance of damaged fibers in H&E-stained sections (Figures 4 and 5A), the number of Ms-IgG+ fibers was low in dysferlin-sufficient muscle but increased over time in dysferlin-deficient muscle, with an approximately 2.5-fold rise between 24 and 48 hours after LSI (Figures 5B and 6).

Figure 6.

Progression of sarcolemmal damage after injury. Immunofluorescence labeling of tibialis anterior muscle cross sections reveals that after injury, the number of fibers that are positive for mouse IgG-positive (Ms-IgG+) entry (a marker of sarcolemmal damage, arrows) increases slowly over several hours and days in dysferlin-deficient A/J, similar to the appearance of damaged fibers in hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Compared with A/J muscle, very few fibers in A/WySnJ muscle are positive for Ms-IgG. Myofiber boundaries are labeled green, with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) conjugated to Alexa 488 (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), and nuclei are labeled blue with DAPI.

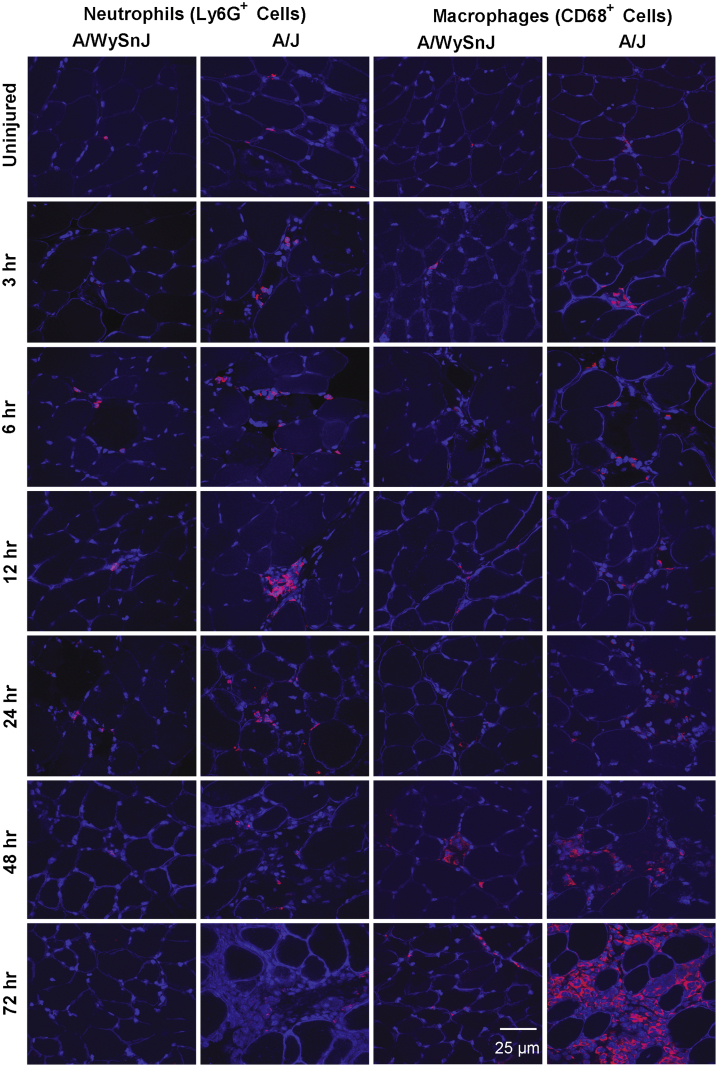

As neutrophils and macrophages are involved in the early and late stages of inflammation, respectively, after contraction-induced muscle injury in healthy muscle,32 we assessed the time course of infiltration of these cells into muscle after LSI (Figures 5C and 7). Neutrophil infiltration was greater in dysferlin-deficient muscle than in control muscle at all time points except for uninjured samples and samples obtained at 6 and 72 hours after LSI (Figure 5C). Macrophage infiltration was low in control muscle but severe in dysferlin-deficient muscle, with a sharp increase between 24 and 48 hours and a further increase between 48 and 72 hours (Figures 5C and 7). The data in Figure 5 indicate that large increases in macrophage infiltration follow the increase in the numbers of damaged fibers and Ms-IgG+ fibers.

Figure 7.

Progression of neutrophil and macrophage infiltration after injury. Frozen sections of muscle collected at different times after injury were immunolabeled with antibodies to neutrophils or macrophages. Dystrophin was also labeled to outline the boundaries of healthy myofibers. Low levels of neutrophil infiltration occur in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle at early times after injury. Macrophage infiltration is more pronounced, however, and becomes very prominent at 48 and 72 hours after large-strain injury. Neutrophils and macrophages are labeled red, and nuclei and myofiber boundaries are labeled blue (DAPI and dystrophin, respectively). Ly6G+, positive for neutrophil marker (MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK).

Analysis of damaged fibers regressed on neutrophils showed that neutrophil infiltration is not a good predictor of myofiber damage (adjusted R2 = 0.000, P = 0.901) (Supplemental Figure S1A). In contrast, the relationship between myofiber damage and the number of macrophages had a good linear fit (adjusted R2 = 0.862, P = 0.002) (Supplemental Figure S1B). However, by studying the relationship between macrophage counts regressed on damaged fibers from a previous time point (adjusted R2 = 0.837, P = 0.007) (Supplemental Figure S1C) and damaged fibers regressed on macrophages from a previous time point (adjusted R2 = 0.686, P = 0.026) (Supplemental Figure S1D), we observed that myofiber damage at a prior time point was a better predictor of macrophage infiltration than the converse. These results suggest that macrophage infiltration occurs largely in response to the appearance of damaged myofibers.

By 14 days after injury, the numbers of infiltrating cells were not significantly different between A/J and A/WySnJ muscle (Supplemental Figure S2).

Flow-cytometry data (Supplemental Figures S3–S5) provided additional evidence that the majority of the mononuclear cells at 72 hours after LSI in dysferlin-deficient muscle are indeed immune cells (CD45+ cells) and not myoblasts (myoD+ cells) or fibroblasts (ER/TR7+ cells) and that, among the infiltrating immune cells (CD45+ cells), macrophages (CD68+ cells) are much more numerous than are neutrophils (Ly6G+ cells).

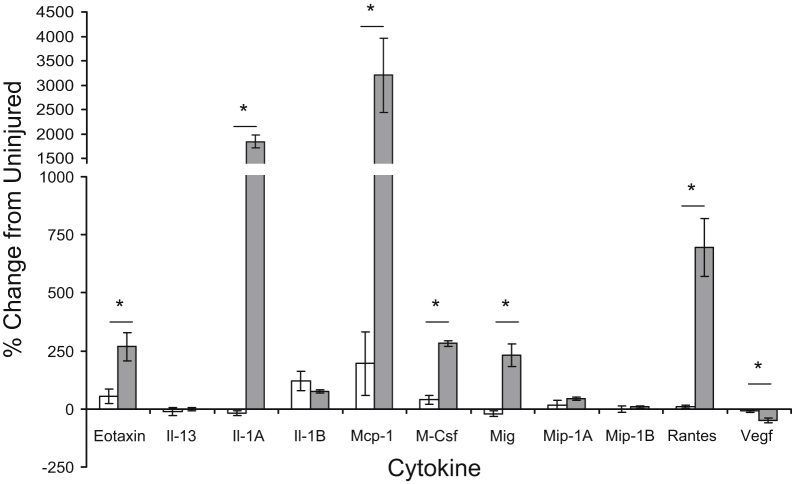

Cytokine and Chemokine Profiles

Cytokine and chemokine profiling of TA muscle homogenates indicated that concentrations of the following cytokines are significantly elevated in dysferlin-deficient muscle compared with those in dysferlin-sufficient muscle at 72 hours after LSI (Figure 8): eotaxin (recruits eosinophils), Il-1A (secreted by monocytes/macrophages, activates tumor necrosis factor α), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (secreted by monocytes/macrophages to recruit more monocytes/macrophages to sites of inflammation), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (promotes proliferation, differentiation, survival, and phagocytosis in monocytes/macrophages), eotaxin (recruits eosinophils), monokine induced by γ-interferon (T-cell chemoattractant), and Rantes (chemoattractant for T-cells, eosinophils and basophils, and recruits leukocytes to site of inflammation). The levels of these cytokines, in picograms per milliliter, in injured versus uninjured A/WySnJ and A/J muscle are given in Supplemental Figure S6. As most of the cytokines and chemokines that are elevated in dysferlin-deficient muscle at 72 hours after LSI are linked to monocyte and macrophage infiltration, these data are consistent with our histological and flow-cytometry data.

Figure 8.

Changes in cytokine levels after injury. Homogenates of injured and uninjured tibialis anterior muscle collected from dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ and dysferlin-deficient A/J mice 72 hours after large-strain injury (LSI) were profiled for 11 cytokines or chemokines that mediate inflammation. The data suggest that molecules related to monocyte/macrophage infiltration, Il-1A, tumor necrosis factor (Tnf)-α, monocyte chemotactic protein (Mcp)-1, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-Csf) are elevated in A/J muscle (gray bars) compared with levels in A/WySnJ muscle (white bars) at 72 hours after LSI. ∗P < 0.05 between strains. Mig, monokine induced by γ-interferon; Mip, macrophage inflammatory protein; Rantes, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted; Vegf, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Macrophage Depletion by Clodronate-Incorporated Liposomes

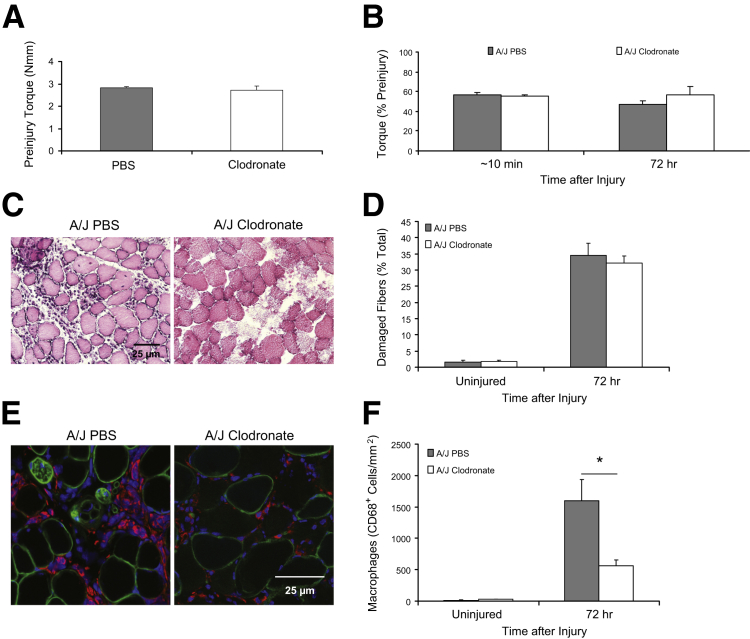

We tested whether depleting macrophages with a single injection of liposomes containing clodronate at 24 hours after LSI would suppress damage to dysferlin-deficient muscle and promote greater recovery of function at 72 hours after LSI. Our results suggest that the treatment of dysferlin-deficient mice with clodronate does not change preinjury torque (Figure 9A), promote faster recovery of function at 72 hours after LSI (Figure 9B), or reduce the number of damaged fibers at 72 hours after LSI (Figure 9, C and D), but that it significantly reduces the number of infiltrating macrophages in muscle (Figure 9, E and F). Treatment with clodronate on the day of injury and 2 days later did not reduce myofiber damage or macrophage infiltration any more than did the administration of a single dose (Supplemental Figure S7).

Figure 9.

Effect of macrophage depletion by clodronate on the response to injury. We used liposomes loaded with clodronate injected IP to reduce the number of circulating monocytes and thus the macrophages that can invade muscle in mice subjected to large-strain injury (LSI). As macrophage infiltration increases steeply between 24 and 48 hours after LSI in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle, we injected animals with 15 μL/g body weight of clodronate-incorporated liposomes 24 hours after LSI. A and B: Treatment of A/J mice with clodronate-incorporated liposomes neither affects preinjury torque nor promotes faster recovery of function at 72 hours after LSI. C–F: Treatment of A/J mice with clodronate-incorporated liposomes does not reduce the number of damaged fibers (C and D; hematoxylin and eosin staining), although it significantly reduces the number of infiltrating macrophages (E and F; immunofluorescence). Macrophages, nuclei, and myofiber boundaries are labeled with antibodies to CD68 (red), DAPI (blue), and antibodies to dystrophin (green), respectively. ∗P < 0.05. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Nmm, Newton millimeter

Discussion

Our aim was to ascertain whether inflammatory cell infiltration in dysferlin-deficient skeletal muscle after injurious exercise was a primary cause of myofiber damage or was secondary to myofiber damage. By using physiological measurements of muscle function, MR imaging in mice, along with histological and pharmacological approaches, we demonstrate that myofiber damage largely precedes inflammatory cell infiltration after exercise-induced injury. We also show that macrophages constitute most of the infiltrating cells and that suppressing the numbers of infiltrating macrophages with clodronate does not improve the fate of dysferlin-deficient muscle subjected to eccentrically-biased exercise. Our results therefore indicate that immune cell infiltration into injured dysferlin-deficient muscle is secondary to myofiber damage, consistent with dysferlinopathies being caused primarily by defects in muscle rather than in the immune system.

One of the most important strengths of the present work is the use of in vivo eccentric exercise to perturb muscle. This approach aims to provide insight into what is likely happening after eccentric loading in skeletal muscle in patients with dysferlinopathies. As eccentric loading in humans is routinely encountered during ambulation, exercise, and activities of daily living, our LSI model is physiologically relevant. The unique aspect of the LSI model of eccentric exercise is that it uses a few repetitions of movement at a high degree of strain to generate a very clear distinction between dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle and dysferlin-sufficient A/WySnJ muscle after exercise.17,18 With other models of eccentric exercise that involve several hundreds of repetitions of movement at a low degree of strain, both dysferlin-deficient and dysferlin-sufficient muscle undergoes significant damage, although the damage in dysferlin-deficient muscle is much greater.17

Our earlier studies have suggested that dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle and dysferlin-suffcient A/WySnJ muscle are equally susceptible to initial injury from LSI, although severe myofiber damage and macrophage infiltration are seen only in the former at 72 hours post injury.16–18 By studying several strains of dysferlin-deficient mice, we have also shown that macrophage infiltration 3 days after injury is a negative predictor of contractile function, and that myofiber damage is a positive predictor of macrophage infiltration.18

Here, by systematically studying muscle at early times after LSI through the hour-72 time point, we find that not only are dysferlin-deficient muscle and dysferlin-sufficient muscle indistinguishable in their susceptibility to initial injury, but they both also partially recover between 3 and 6 hours post-injury. These concepts are evident in the measurements of torque, which partially recover in this time frame in both dysferlin-sufficient and dysferlin-deficient muscle, albeit to a slightly lesser extent in the latter (Figure 1). Similarly, the T2 signal, which is elevated in MR images of dysferlin-deficient muscle soon after injury, decreases by 6 hours after LSI, after which it increases again (Figures 2 and 3). The torque and MR data thus point toward secondary events that come into play several hours after injury and that are likely to trigger myofiber death.

The partial recovery that is seen several hours after injury supports a role for dysferlin other than sarcolemmal resealing, which was initially thought to be the primary function of dysferlin33–35—an idea that has been challenged by more recent evidence.2,5,17 If the absence of dysferlin caused failure of the sarcolemma to reseal, the sarcolemmal lesions that occur after lengthening contractions would lead to progressive myofiber damage, making any partial recovery over several hours, such as that described in Figures 1, 2, and 3, highly unlikely. Further, findings from our histological studies of generalized myofiber damage with H&E staining and of specific sarcolemmal damage with Ms-IgG labeling also suggest that the loss of myofiber integrity progresses slowly in dysferlin-deficient muscle, with a surge in sarcolemmal damage (Ms-IgG+ fibers) occurring as late as 48 hours after injury. These observations are consistent with our earlier data that mechanical resealing of myofibers after injurious lengthening contractions can occur in the absence of dysferlin,17 and with data from others, which suggest that dystrophic features are not mitigated in dysferlin-deficient muscle, even when sarcolemmal resealing is restored with myoferlin overexpression.2

It is indeed intriguing that dysferlin-deficient muscle recovers partially at 3 hours after injury. It is certainly worth investigating what enables this partial recovery and what leads to deterioration of myofiber integrity and contractile function thereafter. These efforts might give us insight into the molecular mechanisms that can be influenced in dysferlin-deficient muscle to maintain the partial recovery that is achieved early on and offset the damage that follows several hours to days after injury.

Our data reveal low levels of myofiber damage in dysferlin-deficient muscle up to 12 hours after injury, after which the numbers of damaged fibers increase sharply and continuously from 24 through 72 hours after injury (Figures 4 and 5). Thus, there is a slow progression of myofiber death in dysferlin-deficient muscle that occurs over an extended time course of several hours and days. This slow progression of myofiber damage might be linked to increased endoplasmic reticulum stress or stress-induced changes in the transverse tubules of dysferlin-deficient myofibers that we have reported, which potentially lead to aberrant adaptive responses to exercise.5,36 It is also possible that some of the recent data from others, which demonstrate increased lipid deposition in dysferlin-deficient muscle and suggest a potential metabolic link to dysferlinopathies, might be related to the late-onset surge in muscle fiber damage after injurious exercise.37,38

Our results also show that, although macrophage infiltration is pronounced in injured dysferlin-deficient muscle, it sharply rises only at 48 hours after injury, after the initial increase in damaged fibers at 24 hours after injury (Figures 5 and 6). The findings from our quantitative comparisons of macrophages to necrotic fibers support the idea that the onset of inflammation trails myofiber damage. Macrophage infiltration in dysferlin-deficient muscle is therefore likely to predominantly be a consequence rather than a primary cause of myofiber damage induced by exercise. This concept does not, however, rule out the possibility that the low levels of macrophage infiltration, which are seen at early time points after injury, might contribute to myofiber damage.

Our findings from studies of liposomes containing clodronate further support the notion that macrophage infiltration is secondary to muscle damage. Despite a depletion of approximately two-thirds of the macrophages that infiltrate injured muscle through systemic administration of clodronate, we observed no significant reduction in the number of damaged fibers (Figure 9 and Supplemental Figure S7) or in the ability of dysferlin-deficient muscle to recover contractile torque at 3 days after LSI. Myofiber damage thus occurs even when macrophage infiltration is significantly reduced, consistent with the idea that the myopathology of dysferlinopathies originates primarily from within the muscle cell and not from inflammation. Since we were unable to completely inhibit macrophage infiltration with clodronate, we cannot rule out the possibility that the small numbers of macrophages that did infiltrate dysferlin-deficient muscle after injury could have contributed to myofiber damage. Further, we also cannot rule out the role of immune cells other than neutrophils and macrophages in myofiber damage. We do however know that inflammation in dysferlinopathic muscle is heightened for a given amount of myofiber damage,18 and it is therefore likely to play a role as a disease modifier.6–9,11 Although suppressing inflammation may benefit patients with dysferlinopathies by reducing its secondary effects on muscle, the findings from the present work suggest that efforts to reduce disease severity in patients with dysferlinopathies should be aimed at developing a better understanding of the factors that lead to delayed myofiber death after eccentric muscle loading.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Hester (Cytokine Core Laboratory), Ferenc Livak (Flow Cytometry Core), Su Xu and Andrew Marshal (Small Animal Imaging Core), and Amy J. Wagers and Jennifer Shadrach (Joslin Diabetes Center) [all from Harvard University (Cambridge, MA)] for training J.A.R. in the techniques used in this study for identifying mononucleated cells in muscle by flow cytometry, and Amudhan Maniar for technical assistance provided in flow cytometry.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the Jain Foundation Inc. (J.A.R. and R.J.B.), Muscular Dystrophy Association218313 (R.J.B.), and NIHR01AR064268 and 1R01AR059179 (R.M.L.) and GM066855, HL69057, and HL085256 (J.D.H.).

J.A.R. and M.E.T. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: Clodronate was a gift of Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany).

Current address of J.A.R., Department of Health Care Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.02.020.

Supplemental Data

Regression analyses on inflammatory cells and damaged myofibers in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle. A and B: Neutrophil infiltration and corresponding myofiber damage at different time points after large-strain injury in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle lack a linear relationship (A, adjusted R2 [Adj Rsqr] < 0.01). However, macrophage infiltration and corresponding myofiber damage at different time points show a linear relationship (B, adjusted R2 = 0.862). C and D: The number of damaged fibers at a preceding time is a good predictor of macrophage infiltration (C, adjusted R2 = 0.837). However, the number of macrophages at a preceding time point is a less reliable predictor of myofiber damage (D, adjusted R2 = 0.686).

Cellular infiltration after large-strain injury (LSI). We studied cellular infiltration over time after injury in hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections and observed that the number of infiltrating cells per visual field is significantly elevated in A/J muscle at 3 and 7 days after injury but not at other times. Data are from three animals per strain at six visual fields per muscle, yielding a sample size of n = 18. ∗P < 0.05 between strains. Uninj, uninjured.

Flow-cytometry data from A/WySnJ muscle. Flow-cytometry data from uninjured and injured tibialis anterior muscle collected from control mice 72 hours after large-strain injury (LSI) show that the majority of the mononuclear cells seen 72 hours after LSI in dysferlin-deficient muscle are indeed immune cells (CD45+ cells, B) and not myoblasts (myoD+ cells, A) or fibroblasts (ER/TR7+ cells, A). B: At 72 hours after LSI, the proportions of CD45+ neutrophils and CD68+ macrophages change only minimally.

Flow-cytometry data from A/J muscle. A and B: Flow-cytometry data from uninjured and injured tibialis anterior muscle collected from dysferlin-null mice 72 hours after large-strain injury show prominent changes in the numbers and the distribution of leukocytes (CD45+ cells) in dysferlin-null muscle. B: In uninjured A/J muscle, the low levels of resident CD45+ leukocytes are made up of similar proportions of neutrophils positive for neutrophil marker (Ly6G+, MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) and CD68+ macrophages. At 72 hours after LSI, there is an increase in the overall number of CD45+ leukocytes, and a vast majority of these cells are macrophages.

Compiled flow-cytometry data from A/WySnJ and A/J muscle. A: CD45+ leukocytes are the most prevalent cell type in injured dysferlin-null muscle 72 hours after large-strain injury. B: Among CD45+ leukocytes, the proportion of CD68+ macrophages is greater than that of neutrophils positive for neutrophil marker (Ly6G+, MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK). n = 2 replicates per marker.

Cytokine profiles of uninjured and injured A/WySnJ and A/J muscle. Cytokine levels in both uninjured and injured muscle from dysferlin-null and control mice are presented in picograms per milliliter. Cytokine levels are not significantly different between uninjured muscle from dysferlin-deficient mice and that from dysferlin-sufficient mice. n = 3 animals per strain. MCP, monocyte chemotactic protein; MCSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MIG, monokine induced by γ-interferon; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Effects of single and multiple clodronate injections. There is no difference in the numbers of damaged myofibers (A) or infiltrating macrophages (B) 72 hours after injury, irrespective of whether clodronate is administered just once at 24 hours after large-strain injury or three times, starting on the day of injury and continued for 2 days thereafter. n = 4, single dosing; n = 2, daily dosing.

References

- 1.Lostal W., Bartoli M., Bourg N., Roudaut C., Bentaib A., Miyake K., Guerchet N., Fougerousse F., McNeil P., Richard I. Efficient recovery of dysferlin deficiency by dual adeno-associated vector-mediated gene transfer. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1897–1907. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lostal W., Bartoli M., Roudaut C., Bourg N., Krahn M., Pryadkina M., Borel P., Suel L., Roche J.A., Stockholm D., Bloch R.J., Levy N., Bashir R., Richard I. Lack of correlation between outcomes of membrane repair assay and correction of dystrophic changes in experimental therapeutic strategy in dysferlinopathy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grose W.E., Clark K.R., Griffin D., Malik V., Shontz K.M., Montgomery C.L., Lewis S., Brown R.H., Jr., Janssen P.M., Mendell J.R., Rodino-Klapac L.R. Homologous recombination mediates functional recovery of dysferlin deficiency following AAV5 gene transfer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wein N., Avril A., Bartoli M., Beley C., Chaouch S., Laforet P., Behin A., Butler-Browne G., Mouly V., Krahn M., Garcia L., Levy N. Efficient bypass of mutations in dysferlin deficient patient cells by antisense-induced exon skipping. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:136–142. doi: 10.1002/humu.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr J.P., Ziman A.P., Mueller A.L., Muriel J., Kleinhans-Welte E., Gumerson J.D., Vogel S.S., Ward C.W., Roche J.A., Bloch R.J. Dysferlin stabilizes stress-induced Ca2+ signaling in the transverse tubule membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20831–20836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307960110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han R., Frett E.M., Levy J.R., Rader E.P., Lueck J.D., Bansal D., Moore S.A., Ng R., Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D., Faulkner J.A., Campbell K.P. Genetic ablation of complement C3 attenuates muscle pathology in dysferlin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4366–4374. doi: 10.1172/JCI42390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uaesoontrachoon K., Cha H.J., Ampong B., Sali A., Vandermeulen J., Wei B., Creeden B., Huynh T., Quinn J., Tatem K., Rayavarapu S., Hoffman E.P., Nagaraju K. The effects of MyD88 deficiency on disease phenotype in dysferlin-deficient A/J mice: role of endogenous TLR ligands. J Pathol. 2013;231:199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kesari A., Fukuda M., Knoblach S., Bashir R., Nader G.A., Rao D., Nagaraju K., Hoffman E.P. Dysferlin deficiency shows compensatory induction of Rab27A/Slp2a that may contribute to inflammatory onset. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1476–1487. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagaraju K., Rawat R., Veszelovszky E., Thapliyal R., Kesari A., Sparks S., Raben N., Plotz P., Hoffman E.P. Dysferlin deficiency enhances monocyte phagocytosis: a model for the inflammatory onset of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2B. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:774–785. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confalonieri P., Oliva L., Andreetta F., Lorenzoni R., Dassi P., Mariani E., Morandi L., Mora M., Cornelio F., Mantegazza R. Muscle inflammation and MHC class I up-regulation in muscular dystrophy with lack of dysferlin: an immunopathological study. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;142:130–136. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzel K., Zabojszcza J., Carl M., Taubert S., Lass A., Harris C.L., Ho M., Schulz H., Hummel O., Hubner N., Osterziel K.J., Spuler S. Increased susceptibility to complement attack due to down-regulation of decay-accelerating factor/CD55 in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. J Immunol. 2005;175:6219–6225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cenacchi G., Fanin M., De Giorgi L.B., Angelini C. Ultrastructural changes in dysferlinopathy support defective membrane repair mechanism. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:190–195. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urtizberea J.A., Bassez G., Leturcq F., Nguyen K., Krahn M., Levy N. Dysferlinopathies. Neurol India. 2008;56:289–297. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.43447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallardo E., Rojas-Garcia R., de Luna N., Pou A., Brown R.H., Jr., Illa I. Inflammation in dysferlin myopathy: immunohistochemical characterization of 13 patients. Neurology. 2001;57:2136–2138. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovering R.M., Roche J.A., Goodall M.H., Clark B.B., McMillan A. An in vivo rodent model of contraction-induced injury and non-invasive monitoring of recovery. J Vis Exp. 2011;51:2782. doi: 10.3791/2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche J.A., Lovering R.M., Bloch R.J. Impaired recovery of dysferlin-null skeletal muscle after contraction-induced injury in vivo. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1579–1584. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328311ca35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roche J.A., Lovering R.M., Roche R., Ru L.W., Reed P.W., Bloch R.J. Extensive mononuclear infiltration and myogenesis characterize recovery of dysferlin-null skeletal muscle from contraction-induced injuries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C298–C312. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roche J.A., Ru L.W., Bloch R.J. Distinct effects of contraction-induced injury in vivo on four different murine models of dysferlinopathy. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:134031. doi: 10.1155/2012/134031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bittner R.E., Anderson L.V., Burkhardt E., Bashir R., Vafiadaki E., Ivanova S., Raffelsberger T., Maerk I., Hoger H., Jung M., Karbasiyan M., Storch M., Lassmann H., Moss J.A., Davison K., Harrison R., Bushby K.M., Reis A. Dysferlin deletion in SJL mice (SJL-Dysf) defines a natural model for limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2B. Nat Genet. 1999;23:141–142. doi: 10.1038/13770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho M., Post C.M., Donahue L.R., Lidov H.G., Bronson R.T., Goolsby H., Watkins S.C., Cox G.A., Brown R.H., Jr. Disruption of muscle membrane and phenotype divergence in two novel mouse models of dysferlin deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1999–2010. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovering R.M., McMillan A.B., Gullapalli R.P. Location of myofiber damage in skeletal muscle after lengthening contractions. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:589–594. doi: 10.1002/mus.21389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Smet A.A., Best T.M. MR imaging of the distribution and location of acute hamstring injuries in athletes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:393–399. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.2.1740393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross T.M., Gibbs N., Houang M.T., Cameron M. Acute quadriceps muscle strains: magnetic resonance imaging features and prognosis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:710–719. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathur S., Vohra R.S., Germain S.A., Forbes S., Bryant N.D., Vandenborne K., Walter G.A. Changes in muscle T2 and tissue damage after downhill running in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:878–886. doi: 10.1002/mus.21986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche J.A., Ford-Speelman D.L., Ru L.W., Densmore A.L., Roche R., Reed P.W., Bloch R.J. Physiological and histological changes in skeletal muscle following in vivo gene transfer by electroporation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C1239–C1250. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00431.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Straub V., Rafael J.A., Chamberlain J.S., Campbell K.P. Animal models for muscular dystrophy show different patterns of sarcolemmal disruption. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roche J.A., Ru L.W., O'Neill A.M., Resneck W.G., Lovering R.M., Bloch R.J. Unmasking potential intracellular roles for dysferlin through improved immunolabeling methods. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:964–975. doi: 10.1369/0022155411423274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Rooijen N., Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiPasquale D.M., Cheng M., Billich W., Huang S.A., van Rooijen N., Hornberger T.A., Koh T.J. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator and macrophages are required for skeletal muscle hypertrophy in mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1278–C1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00201.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Summan M., Warren G.L., Mercer R.R., Chapman R., Hulderman T., Van Rooijen N., Simeonova P.P. Macrophages and skeletal muscle regeneration: a clodronate-containing liposome depletion study. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1488–R1495. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00465.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherwood R.I., Christensen J.L., Conboy I.M., Conboy M.J., Rando T.A., Weissman I.L., Wagers A.J. Isolation of adult mouse myogenic progenitors: functional heterogeneity of cells within and engrafting skeletal muscle. Cell. 2004;119:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tidball J.G. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bansal D., Campbell K.P. Dysferlin and the plasma membrane repair in muscular dystrophy. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bansal D., Miyake K., Vogel S.S., Groh S., Chen C.C., Williamson R., McNeil P.L., Campbell K.P. Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2003;423:168–172. doi: 10.1038/nature01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lennon N.J., Kho A., Bacskai B.J., Perlmutter S.L., Hyman B.T., Brown R.H., Jr. Dysferlin interacts with annexins A1 and A2 and mediates sarcolemmal wound-healing. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50466–50473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mueller A.L., Desmond P.F., Hsia R.C., Roche J.A. Improved immunoblotting methods provide critical insights into phenotypic differences between two murine dysferlinopathy models. Muscle Nerve. 2014;50:286–289. doi: 10.1002/mus.24220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grounds M.D., Terrill J.R., Radley-Crabb H.G., Robertson T., Papadimitriou J., Spuler S., Shavlakadze T. Lipid accumulation in dysferlin-deficient muscles. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demonbreun A.R., Rossi A.E., Alvarez M.G., Swanson K.E., Deveaux H.K., Earley J.U., Hadhazy M., Vohra R., Walter G.A., Pytel P., McNally E.M. Dysferlin and myoferlin regulate transverse tubule formation and glycerol sensitivity. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Regression analyses on inflammatory cells and damaged myofibers in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle. A and B: Neutrophil infiltration and corresponding myofiber damage at different time points after large-strain injury in dysferlin-deficient A/J muscle lack a linear relationship (A, adjusted R2 [Adj Rsqr] < 0.01). However, macrophage infiltration and corresponding myofiber damage at different time points show a linear relationship (B, adjusted R2 = 0.862). C and D: The number of damaged fibers at a preceding time is a good predictor of macrophage infiltration (C, adjusted R2 = 0.837). However, the number of macrophages at a preceding time point is a less reliable predictor of myofiber damage (D, adjusted R2 = 0.686).

Cellular infiltration after large-strain injury (LSI). We studied cellular infiltration over time after injury in hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections and observed that the number of infiltrating cells per visual field is significantly elevated in A/J muscle at 3 and 7 days after injury but not at other times. Data are from three animals per strain at six visual fields per muscle, yielding a sample size of n = 18. ∗P < 0.05 between strains. Uninj, uninjured.

Flow-cytometry data from A/WySnJ muscle. Flow-cytometry data from uninjured and injured tibialis anterior muscle collected from control mice 72 hours after large-strain injury (LSI) show that the majority of the mononuclear cells seen 72 hours after LSI in dysferlin-deficient muscle are indeed immune cells (CD45+ cells, B) and not myoblasts (myoD+ cells, A) or fibroblasts (ER/TR7+ cells, A). B: At 72 hours after LSI, the proportions of CD45+ neutrophils and CD68+ macrophages change only minimally.

Flow-cytometry data from A/J muscle. A and B: Flow-cytometry data from uninjured and injured tibialis anterior muscle collected from dysferlin-null mice 72 hours after large-strain injury show prominent changes in the numbers and the distribution of leukocytes (CD45+ cells) in dysferlin-null muscle. B: In uninjured A/J muscle, the low levels of resident CD45+ leukocytes are made up of similar proportions of neutrophils positive for neutrophil marker (Ly6G+, MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) and CD68+ macrophages. At 72 hours after LSI, there is an increase in the overall number of CD45+ leukocytes, and a vast majority of these cells are macrophages.

Compiled flow-cytometry data from A/WySnJ and A/J muscle. A: CD45+ leukocytes are the most prevalent cell type in injured dysferlin-null muscle 72 hours after large-strain injury. B: Among CD45+ leukocytes, the proportion of CD68+ macrophages is greater than that of neutrophils positive for neutrophil marker (Ly6G+, MCA2387; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK). n = 2 replicates per marker.

Cytokine profiles of uninjured and injured A/WySnJ and A/J muscle. Cytokine levels in both uninjured and injured muscle from dysferlin-null and control mice are presented in picograms per milliliter. Cytokine levels are not significantly different between uninjured muscle from dysferlin-deficient mice and that from dysferlin-sufficient mice. n = 3 animals per strain. MCP, monocyte chemotactic protein; MCSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MIG, monokine induced by γ-interferon; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Effects of single and multiple clodronate injections. There is no difference in the numbers of damaged myofibers (A) or infiltrating macrophages (B) 72 hours after injury, irrespective of whether clodronate is administered just once at 24 hours after large-strain injury or three times, starting on the day of injury and continued for 2 days thereafter. n = 4, single dosing; n = 2, daily dosing.