Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to identify rates of adherence for three outpatient quality indicators noted by Wang and colleagues (2011): (1) influenza vaccine, (2) pneumococcal immunizations, and (3) penicillin prophylaxis in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) in a Medicaid sample. These variables were chosen based on Wang and colleagues’ suggestion that these variables are important for the assessment of the quality of care of children with SCD. We hypothesized that the overall rate of adherence would be poor with adults having worse rates of adherence than children. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Wisconsin State Medicaid database over a 5-year period to assess the preventative medication adherence of individuals with SCD. Preventative medication variables in this study included influenza vaccination, pneumococcal immunizations (PCV7, PPV23), and penicillin prophylaxis. As predicted, the 2003 – 2007 Wisconsin State Medicaid database showed patients with SCD had low adherence in terms of recommended influenza vaccinations (21.58% adherent), PPV23 pneumococcal immunizations (43.47% adherent), and penicillin prophylaxis (18.18% adherent). Pneumococcal immunizations for PCV7 were higher than expected (77.27% adherent). Although children tended to adhere to recommended preventative medications more than adults, overall adherence was low. Although we cannot explain why adherence is low, it is likely due to multiple factors at the patient- and provider-level. We encourage patients and providers to create a partnership to meet adherence recommendations, and we describe our strategies for increasing adherence.

Keywords: quality of life, medication adherence, adults, children, Sickle Cell Disease, Medicaid

Introduction

In the United States, there are approximately 100,000 individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD)[1]; they are typically African American and living in poverty.[2] The additional burden of a low socioeconomic status can make it difficult for these families to satisfy all of their medical needs. Individuals with SCD can experience complications such as severe pain episodes, stroke, acute chest syndrome, and invasive infections which can affect their survival, lead to chronic problems and negatively impact their quality of life. [3] To this end, Wang and colleagues determined 41 quality-of-care indicators for children with SCD, 17 of which focus on routine health care maintenance.[4] Based on the quality of care indicators pertaining to prevention of infection in patients with sickle cell disease, we sought to determine how well children and adults with SCD in Wisconsin are receiving the recommended primary prevention for susceptible infections in sickle cell disease, influenza and pneumococcal.

Using Wisconsin Medicaid claims data of individuals with SCD, we sought to identify rates of adherence for influenza vaccinations, pneumococcal immunizations, and penicillin prophylaxis. We hypothesized that the overall rate of adherence with recommended immunizations and penicillin prophylaxis would be poor and that adults would have worse rates of adherence than children.

Method

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using Wisconsin State Medicaid data from January, 2003 through December, 2007 to assess receipt of recommended care to prevent influenza and pneumococcal infection of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). The database includes 825 patients with SCD who are part of the Wisconsin Medicaid system. Following prior research, a person was considered to have SCD if they had an inpatient hospitalization with a discharge diagnosis of SCD or two outpatient visits at least 30 days apart with a diagnosis of SCD. [5–8] This definition has been established in previously published research and was used to differentiate between SCD and sickle cell trait. Preventative medication variables in this study included: influenza vaccine, Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) and Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), and penicillin prophylaxis. The newest Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) was not assessed as this vaccination had not yet been approved for use.

Influenza Vaccination

The CDC recommends that all individuals receive an influenza vaccine annually, particularly if an individual has a hematologic disorder such as SCD.[9] Adherence rate was calculated by dividing the number of influenza vaccines received by the number of eligible influenza seasons. We defined an influenza season as starting in August and ending in July. We classified individuals into 3 groups representing their level of adherence with recommended immunizations. Individuals were considered adherent if their vaccination rate was greater than or equal to 0.80 per influenza season. Moderate adherence was represented by those individuals whose vaccination rates ranged from 0.50 – 0.79. Individuals were considered to have low adherence if their vaccination rate was greater than zero, but less than 0.50. Individuals were non-adherent if they received no vaccinations. If an individual received a second vaccination within the same influenza season, we assumed it to be a booster shot, and it was counted as part of the original vaccination.

Pneumococcal Immunization – PCV7, PPV23

We examined immunization rates for PCV7 and PPV23. PCV7 is administered to children ages 0 – 2 in a series of four doses. Individuals were included in analyses for PCV7 if they were age zero at the time of enrollment and were enrolled consecutively (i.e., no enrollment gap greater than 3 months). Children were considered adherent if their records corresponded to one of three possible scenarios: (1) receiving at least four doses if enrolled in 2003, 2004, 2005; (2) receiving at least three doses if enrolled in 2006; or (3) receiving at least one dose if enrolled in 2007. Children were classified as moderate-adherent if they received at least one dose, but less than four doses if enrolled in 2003, 2004, 2005 or less than three doses if enrolled in 2006. The latter criterion was included because the final injection occurs when the child is 12 to 15 months old and could have occurred outside the study window of 2003–2007. Children who received no immunizations were considered non-adherent.

During the time of this study period from 2003–2007, PPV23 was recommended to be administered to individuals older than 2 years with a second injection at age 5 years and a booster injection every five years thereafter. Individuals were included in analyses for PPV23 if they were enrolled consecutively (i.e., no enrollment gap greater than 3 months) and were age 2 years or older. They were considered adherent if they received at least one dose of PPV23 during the entire enrollment period. Non-adherence represented individuals who did not receive the immunization during the study period.

Penicillin Prophylaxis

Individuals were included in the analyses if they were enrolled consecutively (i.e., no enrollment gap greater than 3 months) and were age 5 years or younger as this is the standard recommendation for penicillin prophylaxis for this age group. We included children with all genotypes in this analysis in order to compare results to previous reports in the literature; however, because Wang and colleagues restricted their analysis to children with sickle cell anemia, we also examined rates of adherence for a subset of hemoglobin SS (Hb SS) patients, identified by having an Hb SS ICD-9-CM code (282.61, 282.62) and no code for another genotype (other ICD 9 codes for SCD). Adherence rate was calculated using a Medication Possession Ratio (MPR; (Sum of days supplied) / [(number of days from first encounter) – (number of days hospitalized)]). To account for the use of amoxicillin as an alternative treatment, the sum of days supplied for penicillin and amoxicillin were combined in the numerator of the MPR. Individuals were considered adherent if their MPR was greater than or equal to 0.80. Individuals not reaching an MPR of 0.80 but earned an MPR of at least 0.50 were considered moderate-adherent. Patients who had an MPR of 0.49 or less were considered to have low adherence. If no pharmacy claim for penicillin or amoxicillin was recorded, patients were considered non-adherent. Amoxicillin was defined as a preventative medication if patients received a minimum supply of 90 days per year. An MPR of 0.80 has been used in previous studies and is an acceptable benchmark for use to assess adherence.[10–13]

Results

Study Population

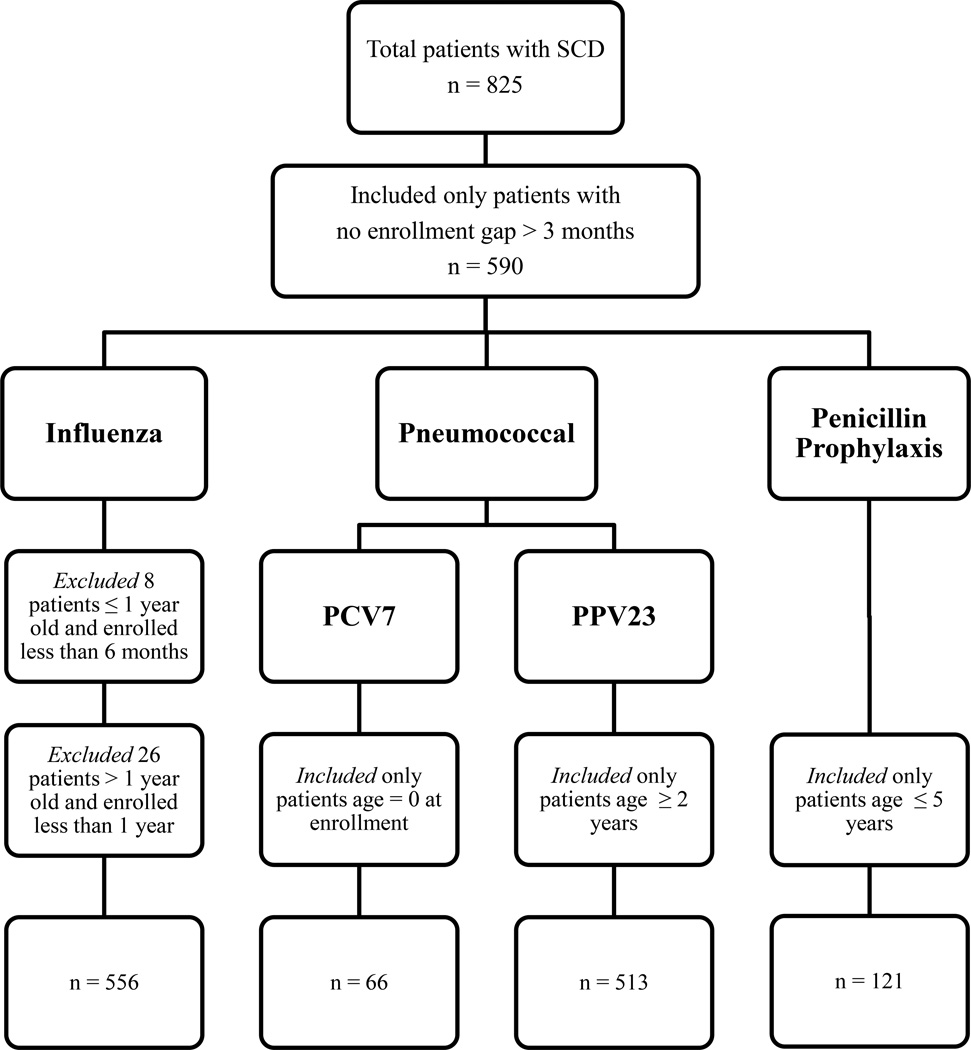

The Wisconsin State Medicaid Database reported information on a total of 825 patients with SCD from 2003 to 2007. Of the total patients, we included 590 patients who were continuously enrolled (i.e., no enrollment gap greater than three months). There were no significant differences in age at enrollment between those who were continuously versus not continuously enrolled. Further, each medication variable required further inclusion/exclusion criteria which are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient eligibility for Influenza, Pneumococcal, and Penicillin Prophylaxis

Influenza Vaccination

Patients (n = 556) were evaluated for adherence with yearly influenza vaccinations. This sample was obtained by excluding eight infants from the final distribution because they were younger than 1 year old at the time of enrollment and had been enrolled for less than six months; thus, their eligibility was indeterminable. An additional 26 individuals were excluded because they were enrolled for less than 12 months. Of the remaining 556 patients, only 21.58% (95% CI: 18.26% – 25.00%) of individuals were adherent with their influenza vaccinations; however, only 27.15% of individuals were non-adherent (Table I). The majority of children and adults had low-to-moderate adherence with influenza rates ranging from 0.01 – 0.79 per season. Examination of the frequency distributions revealed that over one-third of patients in the low adherence group received 0.20 influenza vaccinations per year within the 2003 – 2007 influenza seasons. Additionally, over 90% of patients in the moderate adherence group received at least 0.60 influenza vaccinations per year within the 2003 – 2007 influenza seasons. A chi-square analysis revealed children younger than 18 years had a higher rate of receiving recommended influenza vaccinations over the 5 year study period than adults, p < 0.001.

Table I.

Distribution for Influenza Vaccine Adherence

| n | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≤ 18 years | ||

| Adherenta | 90 | 30.30 |

| Moderate adherentb | 71 | 23.91 |

| Low adherentc | 84 | 28.28 |

| Non-adherentd | 52 | 17.51 |

| Age > 18 years | ||

| Adherenta | 30 | 11.58 |

| Moderate adherentb | 38 | 14.67 |

| Low adherentc | 92 | 35.52 |

| Non-adherentd | 99 | 38.22 |

Note.

Vaccination rate ≥ 0.80 per season;

Vaccination rate 0.50 – 0.79 per season;

Vaccination rate 0.01 – 0.49 per season;

Vaccination rate = 0 per season.

Pneumococcal Immunization

A total of 579 patients were evaluated for adherence with pneumococcal immunizations. Patients were evaluated for PCV7 adherence if they were age 0 at enrollment (n = 66). In Table II, a frequency distribution shows that 77.27% (95% CI: 67.16% – 87.38%) of patients eligible to receive the PCV7 immunization adhered to recommendations. Patients were evaluated for PPV23 adherence if they were age 2 or older (n = 513). Less than half (43.47%; 95% CI: 39.18% – 47.76%) of all eligible patients were adherent. A chi-square analysis revealed children were significantly more adherent (p = 0.008) than adults for PPV23 immunization with approximately half of children ages 2 – 18 years receiving at least one PPV23 immunization during the study period versus only 38% of adults over the age of 18 (Table III).

Table II.

Frequency Distribution for PCV7 Immunization Adherence

Note.

Received at least four doses if enrolled in 2003, 2004, 2005; or received at least three doses if enrolled in 2006; or received at least one dose if enrolled in 2007;

Received at least one dose, but less than four doses if enrolled in 2003, 2004, 2005, or less than three doses if enrolled in 2006;

Received 0 immunizations.

Table III.

Distribution for PPV23 Immunization Adherence

| n | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Age 2 – 18 years | ||

| Adherenta | 118 | 49.79 |

| Non-adherentb | 119 | 50.21 |

| Age > 18 years | ||

| Adherenta | 105 | 38.04 |

| Non-adherentb | 171 | 61.96 |

Note.

Received at least one dose of PPV23 in 2003 – 2007;

Did not receive a dose of PPV23 in 2003 – 2007.

Penicillin Prophylaxis

Of the 121 patients eligible to receive penicillin prophylaxis by being age five years or older, 18.18% (95% CI: 11.31% – 25.05%) met adherence criteria of an MPR greater than or equal to 0.80 (Table IV). The average MPR for those who received prophylaxis was 0.45 (SD = 0.34). Specifically, the average MPR for the adherent group was 0.98 (SD = 0.16). In the moderate-adherent group, the average MPR was 0.64 (SD = 0.10), and in the low-adherent group, the average MPR was 0.23 (SD = 0.14). Examination of adherence for the subset of Hb SS patients (n = 66) showed similar rates of adherence to those reported in Table IV with 22.73% of patients being adherent, 24.24% of patients being moderately adherent, 50.00% being low adherent, and 3.03% receiving no prophylaxis. The average MPR for Hb SS patients who received prophylaxis was 0.49 (SD = 0.33).

Table IV.

Distribution for Penicillin Prophylaxis Adherence

| n | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherenta | 22 | 18.18 |

| Moderate adherentb | 29 | 23.97 |

| Low adherentc | 64 | 52.89 |

| Non-adherentd | 6 | 4.96 |

Note. Prophylaxis includes penicillin or amoxicillin;

MPR ≥ 0.80 per year;

MPR 0.50 – 0.80 per year;

MPR 0 – 0.49 per year;

no prophylaxis

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to determine how well patients with SCD in a Medicaid population in Wisconsin were adherent with recommended care for influenza vaccinations, pneumococcal immunizations, and penicillin prophylaxis. These indicators were chosen based on Wang and colleagues’ rankings as being important for the assessment of the quality of care of children with SCD. [4] As predicted, we found that Wisconsin State Medicaid patients with SCD had low adherence in terms of recommended preventive medications from 2003 – 2007. Although children tended to adhere to recommended preventive medications more than adults, overall adherence was low.

In our sample, children adhered with their influenza vaccinations more often compared to adults. In fact, adults in our sample had poor adherence overall relative to other reported findings on adherence with influenza vaccinations. Using data from the National Health Interview Survey, one study assessed 2008–2009 influenza vaccination adherence in a national sample of adults aged 18–64 with high-risk conditions. [14] They found that adherence was poor with 41.4% of adults reporting they had received a flu shot in the past 12 months. Using similar criteria, data from adults in our study show that only 11.6% were adherent.

To put our results in perspective, it is helpful to compare them to a sample of non-clinical, low-income urban children on Medicaid. Children who received the 4:3:1:3:3:1:3 general vaccination series, which includes the PCV7 immunization, had a median adherence rate of 67.3% with an interquartile range of 41.7% – 94.5%. [15] The majority of children in our sample were adherent with the PCV7 immunization series (77.3%). This may be due to the fact that this series is delivered usually in an office setting at the time of an appointment for a well-child check-up with primary care providers. With the introduction of the new PCV13 series, adherence would be expected to be as good as what we saw for the PCV7 because the immunization series is generally delivered at the time of a visit with the primary care provider.

Our results for PCV7 and PPV23 mirror results found in a small sample of SCD patients in the United Kingdom. [16] Specifically, that study found younger children had the best immunization record (60% adherent), followed by older children (40% adherent). Adults had the worst levels of adherence (12%) in the UK study, which is true of our study, although our adherence was higher than the UK with 38% of adults receiving at least one PPV23 during the five-year study period. It is important to note that our results for PPV23 are based on guidelines at the time the data was collected (2003 – 2007). Since then, recommendations have changed to allow for fewer vaccinations for adults. Having fewer required vaccinations may lead to improved adherence.

The results for penicillin prophylaxis adherence in our study are similar to previous research in sickle cell disease patients in the United States. Researchers using the Tennessee Medicaid database found that 60% of infants with SCD did not have prophylactic antibiotic prescriptions filled within the recommended period. [17] Similarly, a retrospective cohort study of Missouri Medicaid data revealed that children with SCD refill their daily medications 58.4% of the time, and adherence to penicillin prescriptions, specifically, was 54.9%. [18] Although the majority of our patients had at least some adherence to prophylaxis, only 18% achieved a benchmark MPR of 0.80 or higher, and the overall MPR for patients who received prophylaxis (0.45) was low. Additionally, the subset of Hb SS patients who received prophylaxis was also low showing there is great need for improvement in adherence. It is possible that some patients obtained their penicillin from another source, lowering the appearance of adherence; however, because these patients are using Medicaid, we suspect utilization of alternate sources would be a rare circumstance given the out-of-pocket expense it would require.

When comparing adherence across the three types of preventative medications we examined, patients were most adherent for the PCV7 vaccine and least adherent for penicillin prophylaxis. This difference is not surprising given the nature of the administration of these medications. PCV7 is given to infants in a clinic setting, whereas penicillin prophylaxis is a twice-daily medication taken at home. Administration of the penicillin prophylaxis is a large commitment for families and patients, and it is likely more challenging to remain adherent. Regardless of these differences in adherence, children with SCD are still more likely than African American children in the general population to have invasive pneumococcal disease making it all the more necessary for patients to be adherent to their preventative medications.[19]

Research has shown that when patients are adherent to one drug, their overall adherence to other medications is higher. [18] If our patients are not managing their preventative medications, it is unlikely that they will manage a daily medication such as hydroxyurea, even though it will improve their quality of life. Thus, although we have found adherence levels comparative to other studies, the overall message is that SCD patients are not receiving their recommended vaccinations and penicillin prophylaxis as we would hope.

Several studies have tried to determine factors that influence adherence to medication; however, there is no clear evidence one way or the other. One reason for this ambiguity could be that there are multiple contributing factors to non-adherence, and these factors are not the same for everyone. In fact, a recent study listed six medication adherence phenotypes meant to distinguish between different patient behaviors and barriers that patients face. [20] The authors suggest that by understanding the patient’s phenotype of non-adherence, we can target appropriate solutions. For example, if the patient’s barrier is a lack of understanding about the importance of their medication, we can improve adherence by educating the patient. Other researchers have suggested that both patients and providers could be responsible for the lack of adherence. [17] Ultimately, it seems clear that adherence should be a partnership between the patient and provider.

Although much of the responsibility ultimately falls to the patient, healthcare providers need to seize opportunities to check that their patients are 1) aware of the recommended immunizations and vaccinations, and 2) are up-to-date. Opportunities for these conversations with patients arise during routine and non-routine hospital visits. In fact, some research has shown that healthcare providers can improve their rate of administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines with continued education about the necessity of vaccine administration. [21] This is particularly important for ensuring healthcare providers remain up-to-date with the CDC’s current recommendations for vaccines.

Another important option for improving adherence may be for patients to rely on their medical home. For young children, having a medical home has been associated with greater vaccination coverage. [22] For children with SCD, in particular, one recent study noted that only 11% met the criteria for having a medical home. [23] It is possible that increasing the utilization of a medical home can help promote adherence to preventative medications. This option may be particularly helpful for adults allowing for less utilization of emergency departments and subspecialists as they transition out of pediatric care. [24]

There are limitations associated with using a single state Medicaid database that need to be addressed. First, this database only includes those patients who are publicly insured through Medicaid and does not include individuals with private insurance or no insurance. Second, the database includes historical cohort data from 2003 through 2007. Future studies should examine adherence using a more recent cohort to determine current rates of adherence as well as to determine whether there has been any improvement or decline in adherence. Third, we were not able to determine whether patients were seeing a primary care physician or subspecialist for their preventative medications. Patients could have received preventative medications from a primary care physician except for PPV23 which is administered by a subspecialist.

This study has important implications for healthcare workers and researchers who work with SCD patients. The majority of the African American population in Wisconsin lives in and around the Milwaukee area [25] making our facility at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin one of the most utilized in the state for the treatment of pediatric SCD. Because our center serves a large portion of the SCD population in Wisconsin, we hope to use this information to improve our adherence rates. In particular, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin now utilizes a program to keep patients up-to-date for influenza vaccinations. We hope that this program will provide us with the ability to follow, and increase, our patients’ adherence over time. In addition, we have been working with a partnering hospital to establish a better transition from pediatric care to adult care for our SCD patients that now includes adult sickle cell disease providers and a dedicated nurse. We are hopeful that programs like this can help adults improve their adherence.

References

- 1.Brousseau DC, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, et al. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the united states: National and state estimates. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:77–78. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panepinto JA, Pajewski NM, Foerster LM, et al. Impact of family income and sickle cell disease on the health-related quality of life of children. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panepinto JA, Bonner M. Health-related quality of life in sickle cell disease: Past, present, and future. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:377–385. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang CJ, Kavanagh PL, Little AA, et al. Quality-of-care indicators for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128:484–493. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar SM, Arbogast PG, Mitchel E, et al. Medical care utilization and mortality in sickle cell disease: A population-based study. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:262–270. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amendah DD, Mvundura M, Kavanagh PL, et al. Sickle cell disease-related pediatric medical expenditures in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S550–S556. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: Lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:863–865. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leschke J, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, et al. Outpatient follow-up and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:406–409. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Persons for whom annual vaccination is recommended: Influenza prevention and control recommendations. 2012 Nov 30; http://www.Cdc.Gov/flu/professionals/acip/persons.Htm.

- 10.Candrilli SD, O'Brien SH, Ware RE, et al. Hydroxyurea adherence and associated outcomes among medicaid enrollees with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:273–277. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, et al. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:565–574. doi: 10.1002/pds.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ritho J, Liu H, Hartzema AG, et al. Hydroxyurea use in patients with sickle cell disease in a medicaid population. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:888–890. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan LB, Vekeman F, Sengupta A, et al. Persistence and compliance of deferoxamine versus deferasirox in medicaid patients with sickle-cell disease. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams WW, Lu PJ, Lindley MC, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among adults—national health interview survey, united states, 2008–09 influenza season. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(suppl):65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu LY, Cowan N, McLaren R, et al. Spatial accessibility to providers and vaccination compliance among children with medicaid. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1579–1586. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard-Jones M, Randall L, Bailey-Squire B, et al. An audit of immunisation status of sickle cell patients in Coventry, UK. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:42–45. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.058982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren MD, Arbogast PG, Dudley JA, et al. Adherence to prophylactic antibiotic guidelines among medicaid infants with sickle cell disease. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2010;164:298–299. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel NG, Lindsey T, Strunk RC, et al. Prevalence of daily medication adherence among children with sickle cell disease: A 1-year retrospective cohort analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:554–556. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne AB, Link-Gelles R, Azonobi I, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among children with and without sickle cell disease in the united states, 1998–2009. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182a11808. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcum ZA, Sevick MA, Handler SM. Medication nonadherence: A diagnosable and treatable medical condition. JAMA. 2013;309:2105–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rees S, Stevens L, Drayton J, et al. Improving inpatient pneumococcal and influenza vaccination rates. J Nurs Care Qual. 2011;26:358–363. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31821fb6bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allred NJ, Wooten KG, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19- to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:S4–S11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raphael JL, Rattler TL, Kowalkowski MA, et al. The medical home experience among children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:275–280. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: Establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:116–120. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2006–2010 5-year estimates; generated using American factfinder. 2013 May 7; http://factfinder2.Census.Gov.