Significance

The evolution of Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere occurred in two major steps, the first of which took place approximately 2.4 billion years ago. Following the initial rise of oxygen, carbon isotope evidence indicates the burial of vast quantities of organic carbon and the production of correspondingly large amounts of oxygen. However, if not accompanied by an additional supply of carbon, the extreme levels of organic carbon burial imply nonphysically low atmospheric pCO2 levels. Here we propose that the initial rise in O2 led to the oxidation of a large preexisting reservoir of siderite (FeCO3), which provided the necessary carbon for the burial of organic matter, production of further O2, and substantial accumulation of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere for the first time.

Keywords: carbon isotopes, oxygen, siderite, carbon cycle, Great Oxidation Event

Abstract

The Paleoproterozoic Lomagundi Event is an interval of 130–250 million years, ca. 2.3–2.1 billion years ago, in which extraordinarily 13C enriched (>10‰) limestones and dolostones occur globally. The high levels of organic carbon burial implied by the positive δ13C values suggest the production of vast quantities of O2 as well as an alkalinity imbalance demanding extremely low levels of weathering. The oxidation of sulfides has been proposed as a mechanism capable of ameliorating these imbalances: It is a potent sink for O2 as well as a source of acidity. However, sulfide oxidation consumes more O2 than it can supply CO2, leading to insurmountable imbalances in both carbon and oxygen. In contrast, the oxidation of siderite (FeCO3 proper, as well as other Fe2+-bearing carbonate minerals), produces 4 times more CO2 than it consumes O2 and is a common—although often overlooked—constituent of Archean and Early Proterozoic sedimentary successions. Here we propose that following the initial rise of O2 in the atmosphere, oxidation of siderite provided the necessary carbon for the continued oxidation of sulfides, burial of organic carbon, and, most importantly, accumulation of free O2. The duration and magnitude of the Lomagundi Event were determined by the size of the preexisting Archean siderite reservoir, which was consumed through oxidative weathering. Our proposal helps resolve a long-standing conundrum and advances our understanding of the geologic history of atmospheric O2.

Reconstructing the geologic history of atmospheric oxygen is among the foremost scientific challenges of our time (1). The level of atmospheric oxygen (p) without doubt played a key role in the evolution of the Earth System (2), exerting a major influence on the biosphere, especially the evolution of metazoans (3). With no direct way of measuring oxygen concentrations in deep geologic time, the stable isotopes of carbon recorded in marine limestones provide key constraints (4). Carbon enters the ocean−atmosphere system through volcanoes and weathering of carbon-bearing sedimentary rocks and can exit in one of two ways: (i) uptake during photosynthesis and burial of organic carbon leading to production and (ii) reaction during weathering and formation of in the ocean. The carbon isotopic record tells us how carbon was partitioned between these two sinks: A value of 0‰ indicates that ∼80% of incoming carbon was buried as carbonate carbon and 20% as organic carbon. Positive excursions in are unusual and indicate that a larger fraction of carbon was fixed and buried as organic carbon and, with it, a larger amount of was produced.

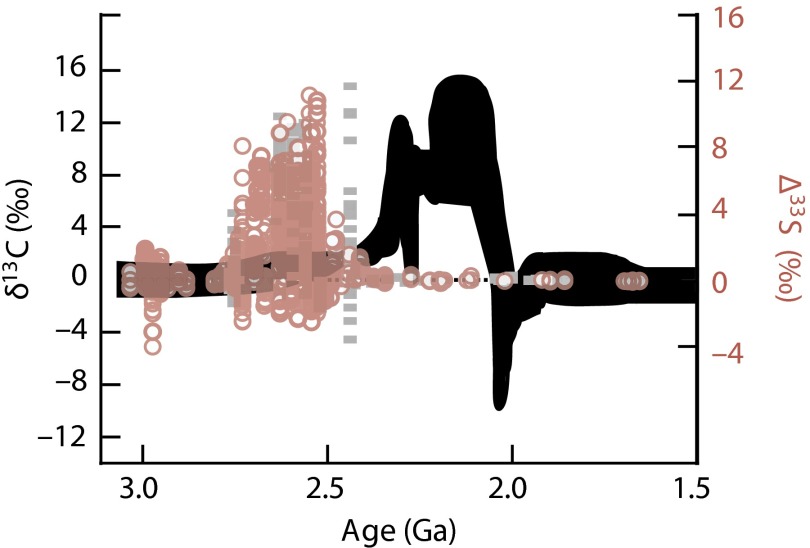

Following the indications for the first rise of in the atmosphere (5, 6) is the largest and most protracted period of 13C enrichment in the geologic record, known as the Lomagundi Event (Fig. 1). Limestones and dolostones with extreme carbon isotopic values of 8‰ to greater than 15‰ occur globally (6–8), and a duration of between 128 million years (m.y.) and 249 m.y. is suggested by current age constraints (9). The highly elevated C values indicate the burial of tremendous amounts of organic carbon, and the production of correspondingly vast amounts of O2. In fact, the duration and magnitude of the isotopic excursion in C bespeak of fluxes so large that they challenge our understanding of geochemical cycles. Calculations indicate an integrated production of far larger amounts of O2 than currently exist—or likely ever existed—in Earth’s atmosphere, implying the concurrent existence of effective sinks (10).

Fig. 1.

Archean and Proterozoic carbon and sulfur isotopic data. The Lomagundi Event refers to the interval of highly positive C values (black band) between 2.3 Ga and 2.0 Ga (9). The preceding collapse in the range of values (in red and gray) indicates the increase in atmospheric levels from vanishing Archean levels for the first time (5). Adapted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature ref. 35.

A second, hitherto unrecognized problem exists as well. The elevated C values indicate a repartitioning of the incoming carbon in favor of organic carbon burial. However, if the total amount of carbon entering the ocean−atmosphere system remains unchanged, then any increase in the organic carbon burial flux can only be at the expense of the other output flux, that of carbonate carbon. However, the burial of carbonate carbon represents the burial not only of carbon but also of alkalinity, and thus a decrease in its magnitude demands a commensurate decrease in the input of alkalinity from weathering. Critically, values of +10‰ indicate the burial of so large a fraction of organic carbon that a 90% reduction in carbonate burial, and hence weathering, would have been necessary to balance it (see SI Appendix for calculation). Assuming that weathering is proportional to p to the 0.3 power (11, 12), a 90% reduction in weathering would have entailed a decline from a p baseline of 10,000 ppm to single part per million levels. Consequently, in the face of such high levels of organic carbon burial, without an additional source of or sink for alkalinity, a near-complete shutdown of weathering would have been required to balance the inputs and outputs of carbon.

The more plausible alternative is that during Lomagundi times processes that consume and release compensated the inferred imbalances such that p levels were bolstered and p levels moderated. The oxidation of sedimentary sulfides is an attractive option for alleviating the attendant imbalances, as it is a potent sink for oxygen (13) and, in conjunction with acidification of carbonates, a source of (14). The oxidation of sulfides following the first rise of oxygen is supported by evidence including the disappearance of detrital pyrites (15, 16), the appearance of sedimentary evaporites (17), and Cr enrichment in iron-rich sedimentary rocks indicating a highly acidic weathering regime (18).

Nonetheless, sulfide oxidation alone could not have fully compensated the imbalances resulting from the elevated burial of organic carbon during the Lomagundi Event. Close examination of Eqs. 1–3 reveals that pyrite oxidation coupled to acidification of carbonates leads to unavoidable imbalances in carbon and oxygen due to the stoichiometry of the overall reaction, which consumes more oxygen than it releases carbon. The oxidation of 4 mol of pyrite requires 15 mol of (Eq. 1), while the associated acidification of carbonates can release at most only 8 mol of (Eq. 2). Thus, on the whole, pyrite oxidation consumes 15 mol of but produces only 8 mol of (Eq. 3).

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

However, the continued oxidation of pyrite requires the burial of 15 mol of CO2 as organic carbon (Eq. 4)—7 mol more than can be supplied by pyrite oxidation coupled to the acidification of carbonates.

| [4] |

Conversely, if the amount of CO2 required by organic carbon burial is assumed to balance the amount that can be supplied by pyrite oxidation coupled to acidification of carbonates (8 mol), not enough oxygen is produced during organic carbon burial (8 mol) to balance the demand of pyrite oxidation (15 mol), such that any pyrite oxidation would grind to a halt. Consequently, the oxidation of sulfides cannot be a sustained source of carbon over geological timescales, even during intervals of highly elevated oxygen production, and much less so during periods when this is not the case (14).

Here we suggest that siderite oxidation (including siderite proper, FeCO3, as well as other bearing carbonate minerals) provided the necessary during Lomagundi times. Siderite is a major constituent of Archean and Early Proterozoic sediments: It is extremely abundant in banded iron formations, often even more so than iron oxides (19). Siderite is also found in anomalously high concentrations in Proterozoic limestones and dolomites (20), where it arises from the replacement of Ca2+ and Mg2+ by in the carbonate mineral lattice. Crucially, the oxidation of siderite produces 4 times more than it requires . The oxidation of siderite (Eq. 5) followed by photosynthetic CO2 fixation (Eq. 6) is a net source of oxygen (Eq. 7),

| [5] |

| [6] |

| [7] |

Hence, in principle, the burial of the CO2 evolved from siderite oxidation as organic carbon can produce oxygen 3 times in excess of the O2 required by siderite oxidation, with the surplus going to the oxidation of sulfide, oxidation of reduced crustal iron, and the accumulation of free O2 (21).

Calculations and Numerical Results

Siderite oxidation would have contributed to transient 13C enrichment of the exogenic reservoir in two principle ways. First, by the delivery of 13C enriched carbon. Massively bedded Archean and Proterozoic marine siderites have an average carbon isotopic composition of 0.9‰ (19), ∼4‰ more enriched than the average weathering input. Second, siderite oxidation could drive up exogenic C by changing the ratio of organic to carbonate carbon burial fluxes as governed by the stochiometries of siderite, sulfide, and iron silicate oxidation. Consider first the oxidation of siderite coupled to the burial of organic carbon and oxidation of iron silicates (Eq. 8):

| [8] |

Neither O2 nor CO2 appears in the above reaction; it is balanced for both. The burial of 1 mol of organic carbon consumes 1 mol of CO2, which is supplied by the oxidation of 1 mol of siderite. One quarter of the resulting mol of O2 that is produced goes to the oxidation of siderite, while the other 3/4 mol goes to the oxidation of iron silicates. Siderite oxidation coupled to iron silicate oxidation and organic carbon burial can thus drive an increase in the C of the exogenic pool with no imbalances in oxygen or carbon.

Consider next the effects of sulfide oxidation (Eq. 3) on the carbon cycle: The acidity produced by sulfide oxidation is neutralized by the release of calcium from limestones and silicates, which releases carbon. We need not distinguish between the direct acidification of limestones by sulfuric acid (Eq. 2) and the sulfuric acid weathering of silicates; both reactions equally lead to net release of carbon dioxide: the first by the conversion of carbonate to CO2, and the second by replacing carbonic acid weathering with sulfuric acid weathering and thus allowing volcanic CO2 to go unconsumed. Equally, viewed from the product side, the production of calcium sulfate makes available carbon that would otherwise be tied to the burial of calcium carbonate. Coupled to siderite oxidation, a CO2 and O2 neutral reaction can be written (Eq. 9):

| [9] |

We can use Eqs. 8 and 9 to construct a carbon isotopic mass balance. We assume that some fraction, , of the siderite is oxidized according to Eq. 8, and the rest, , according to Eq. 9. From the resulting isotopic mass balance, an expression can be obtained for the isotopic composition of limestones as a function of the siderite oxidation flux (see SI Appendix):

| [10] |

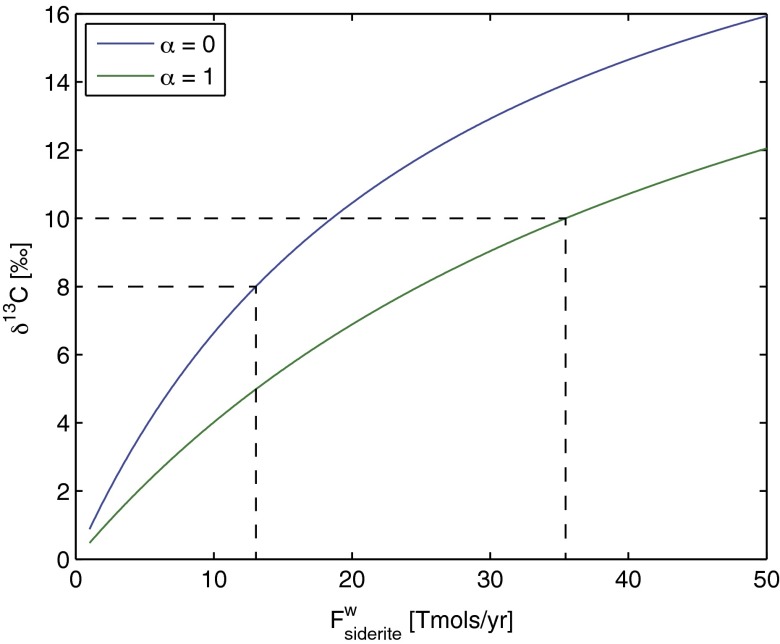

where . When the siderite oxidation flux is zero, Eq. 10 gives the long-term isotopic composition of marine carbonates of 0‰. As the net flux of siderite oxidation increases, so does the isotopic value of marine carbonates (Fig. 2). For the middle range of values observed in carbonates belonging to the Lomagundi Event , a siderite oxidation flux between 13 Tmol/y (1012 mol/y) and 35.5 Tmol/y is required (dotted lines in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of siderite oxidation and organic carbon burial on the carbon isotopic composition of the exogenic carbon pool. Calculated according to Eq. 10 using a total carbon input flux of 50 Tmol/y. The range of values observed during Lomagundi times, 8‰ C 10‰, require the oxidation of 13–35.5 Tmol/y (1012 mol/y) of siderite (dashed lines), depending on the relative proportions of siderite oxidized together with sulfide (, blue line) versus siderite oxidized together with FeSiO3 (, green line).

To further evaluate the time-dependent behaviors of CO2 and O2, as well as place bounds on the quantities of reactants involved in the Lomagundi Event, we use a simple model of the sedimentary and oceanic carbon cycles. The model includes the sedimentary reservoirs of organic and carbonate carbon, sulfate and sulfide sulfur, siderite, and reduced iron. It also includes the oceanic reservoirs for calcium, sulfate, phosphate, and alkalinity, and the ocean−atmosphere reservoirs for carbon and oxygen. The carbonate system parameters (pH, pCO2, and the carbonate saturation, ) are calculated at every time step. Full model description and code are available in SI Appendix. We set the initial model conditions to postulated pre-Lomagundi conditions: low sulfate (50 M), low O2 (10–5 present atmospheric level), and high pCO2 (10,500 ppm).

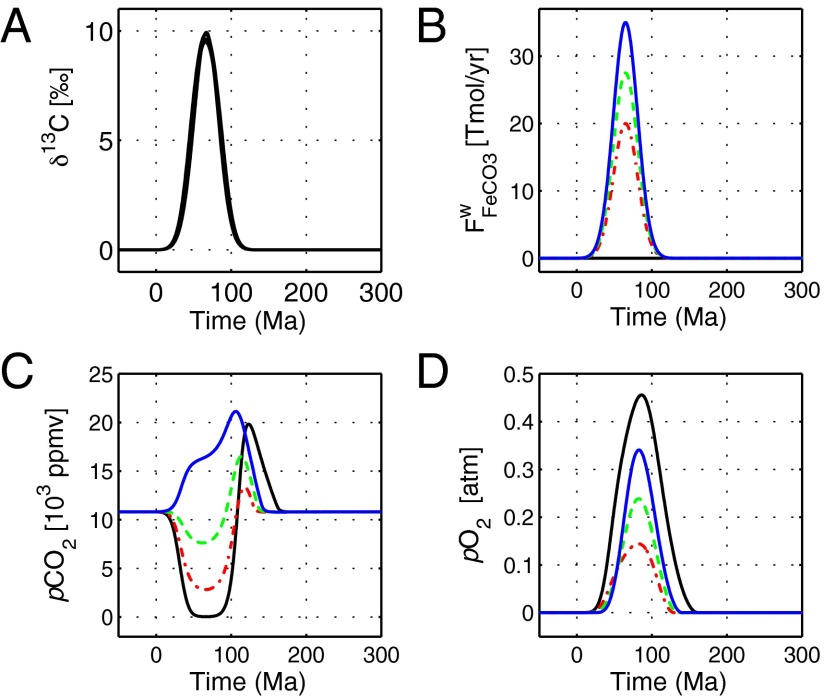

We first use the model to explore the impacts of organic carbon burial without accompanying oxidation of siderite. We then add the oxidation of siderite and iron silicates and evaluate the resultant changes in pCO2 and pO2. Forcing organic carbon burial for 130 m.y. so that a +10‰ positive C excursion arises results in a dramatic drop in pCO2 (Fig. 3, solid black line). Without additional input from siderite oxidation, organic carbon burial consumes more carbon than can be supplied by sulfide oxidation forcing a precipitous decline in pCO2 to 46 ppm. Following the cessation of this forcing, as organic carbon burial ceases to consume carbon, and sulfide oxidation begins to consume oxygen at a rapid pace, pCO2 rises to 20 × ppm (2× model baseline). The extremely low minimum pCO2 levels that result in this model run suggest that this scenario is implausible. Conversely, with increasing input of carbon from siderite oxidation, minimum pCO2 levels increase (Fig. 3). With a low amount of FeCO3 oxidized (813 Emol, 1018 mol), pCO2 is reduced from the initial 10,800 ppm to 2,800 ppm (red dash-dotted line in Fig. 3). Oxidizing 1,118 Emol of FeCO3 results in a more moderate pCO2 decline to 7,600 ppm (green dashed line in Fig. 3). Increasing the amount of siderite to 1,424 Emol of FeCO3 results in pCO2 not being reduced by any significant amount (solid blue line in Fig. 3). In all cases, the modeled p rises substantially in association with the positive C excursion. The minimum modeled p is 0.14 atm, or approximately two thirds the modern value, lending support to previous suggestions for substantial accumulation in association with the Lomagundi Event (13, 22).

Fig. 3.

Dynamic model runs simulating the Lomagundi Event. In all model runs, organic carbon burial is increased such that a large (+10‰) positive C excursion lasting 130 m.y. is generated (A). With increasing amounts of siderite and iron silicate oxidation (B), minimum p values rise (C), while peak p values decline (D). When organic carbon burial is not accompanied by any siderite oxidation (solid black line), the deficit in for organic carbon burial drives pCO2 to the extremely low level of 46 ppm. With a small amount of siderite oxidized (red dash-dotted line), p declines to a more moderate 2,800 ppm; with an intermediate amount (dashed green line), p declines to 7,600 ppm; and with a high amount (blue solid line), p does not decline at all. In all cases, rises in association with the excursion. Minimum modeled p is 0.14 atm, or approximately two thirds the modern value, suggesting substantial oxygen accumulation in association with the Lomagundi Event. Overall, the modeling indicates that, when accompanied by siderite oxidation, the Lomagundi Event can be successfully accommodated without it giving rise to nonphysical ocean or atmospheric chemistries.

We also tabulate the cumulative amounts of reactants consumed (“Consumed” columns in Table 1) and products generated (“Produced” columns in Table 1) during the three model runs, and present them together with estimates of crustal masses culled from the literature. For siderite, the amounts required for driving the Lomagundi Event were likely available for oxidation at 2.3 Ga. In the case of carbonate carbon, its weathering in the first two runs is actually reduced due to the lower p, and in all cases, our calculated amount of carbonate that was required constitutes only a small fraction of the existing reservoir. Our calculated mass of products, in particular of and Corg, fall within the range of values estimated for modern reservoir sizes. Our calculated gypsum production stands at roughly 20% of the total modern exogenic sulfur reservoir (which likely existed entirely as sulfide sulfur prior to the Lomagundi event). Our calculated value is consistent with evidence for moderate sea water sulfate concentrations and gypsum precipitation at 2.1 Ga (23). Thus, the oxidation of a large preexisting sedimentary reservoir of siderite, following the rise of O2 in the atmosphere, can successfully accommodate the existence of a large, protracted, positive carbon isotope excursion, driven by organic carbon burial, without it resulting in nonphysical ocean or atmospheric chemistries or violation of global mass balance constraints.

Table 1.

Total amounts of reactants consumed and products generated, in Emol ( mol), for the three model runs that are accompanied by varying levels of siderite oxidation

| Consumed | Produced | ||||||||

| Duration | FeS2 | CaCO3 | FeSiO3 | FeCO3 | Fe2 O3 | CaSO4 | CH2 O | ||

| Model Run | |||||||||

| Low | 130 m.y. | −41 | 644 | −2,441 | −813 | 1,648 | 82 | 806 | 0.88 |

| Intermediate | 130 m.y. | −45 | 34 | −3,051 | −1,118 | 2,108 | 91 | 1,205 | 0.90 |

| High | 130 m.y. | −50 | −574 | −3,662 | −1,424 | 2,568 | 101 | 1,604 | 0.92 |

| Estimated crustal reservoir sizes | 84–294 | 2,800–9,600 | 2,886 | (350–3,000) | 4,000 | 81–240 | 675–1,700 | ||

The ratio between the amount of siderite oxidation accompanied by FeSiO3 oxidation (Eq. 8) versus siderite oxidation accompanied by oxidation (Eq. 9) is given by . Estimated reservoir sizes given are for the present, except for siderite, which is given at 2.3 Ga. The correspondence between the calculated values and the crustal estimates indicates that, with siderite oxidation, the Lomagundi Event can successfully be explained without violation of global mass balance constraints. See SI Appendix for references and additional details.

Discussion

Our proposal that siderite oxidation played a key role in the Lomagundi Event helps resolve several conundrums related to its timing and duration. It has been pointed out (4) that the order of oxygenation (as indicated by the disappearance of the mass independent fractionation of sulfur isotopes; Fig. 1) and the organic carbon burial event (as evidenced by the positive C values 200 m.y. later) is reversed from what would be expected if organic carbon burial was responsible for the rise of O2. Our mechanism offers a plausible explanation for the observed order of events. Geologically slow processes, such as changes in plate tectonic regime, secular mantle cooling, or a shift in the locus of volcanism leading to changes in volcanic gas composition [among numerous proposed mechanisms (24)], were likely responsible for driving a gradual long-term increase in pO2. We postulate that superimposed on this long-term increase in atmospheric pO2 was a pulse of O2 production: Once the threshold for oxidation of siderite was surpassed, a positive feedback was triggered whereby siderite oxidation supplied for organic carbon burial, which in turn supplied oxygen for further siderite, sulfide, and iron silicate oxidation. The siderite was likely oxidized both subaerially, where exposed, and in reaction with oxidizing groundwaters that would have penetrated the continental shelves and intracratonic basins for the first time (25). Concomitantly, the burial of siderite would have diminished as a result of a reduction in the inputs of from both terrestrial weathering and hydrothermal inputs. Delivery of ferrous iron from terrestrial settings would have ceased under a high-O2 atmosphere, and hydrothermal inputs of reduced iron would have likely diminished in an ocean bearing appreciable quantities of sulfate (26). The oxidation of siderite and burial of organic carbon would have continued until the siderite reservoir was consumed, on the timescale of hundreds of million years. Once the large Archean reservoirs of reduced minerals were exhausted and abundant crustal oxidants were produced, little siderite remained to fuel organic carbon burial, and O2 production was curtailed.

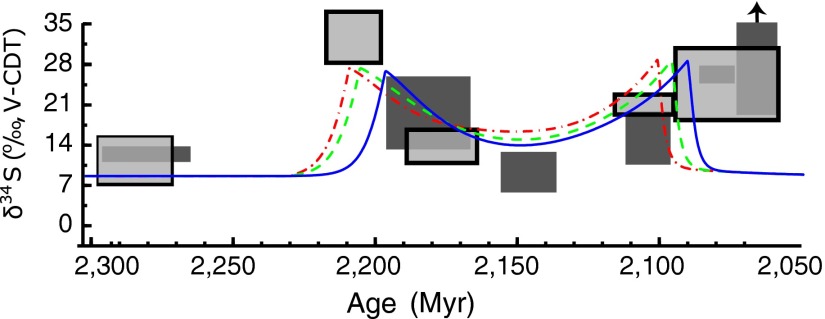

Our model, which shows an initial drop in pCO2 (Fig. 3), is further consistent with the occurrence of glacial episodes preceding the Lomagundi Event. It is also consistent with the pattern of S changes that occur during the Lomagundi interval. Measurements of both carbonate-associated sulfate (CAS) and evaporite sulfate (27) show an increase in S followed by a protracted decrease, which coincides with the peak of the C excursion, followed by another increase (Fig. 4). These trends have been interpreted as reflecting the balance of sulfide burial to sulfide oxidation in response to changing O2 levels, during, and in the wake of, the Lomagundi Event (27). Our model agrees with and refines this interpretation. In our model, there is an initial increase in S that is driven by an increase in the fractionation factor associated with an increase in sulfate concentrations (28). The S values then decline as large amounts of relatively light sulfate (+7‰) are delivered to the ocean from the oxidation of sulfides, then rise again as that flux wanes, and finally fall as sulfate concentrations decline once more. In the model, 14–18% of the total S reservoir is oxidized to sulfate and sulfate concentrations in the ocean reach a peak of 4 mM, which is ∼15% of their modern value. Following this modest burst of sulfate production and deposition during the Lomagundi Event, the S of sedimentary pyrite indicate that pyrite burial became predominant once more, and that dominance was maintained until the second rise of oxygen in the Neoproterozoic (29).

Fig. 4.

S data from Lomagundi age sediments (27). Light gray boxes are S values measured in sulfate from evaporites (gypsum and anhydrite), and dark gray boxes are S measured in carbonate associated sulfate. Lines are the same model outputs as in Fig. 3. In the model, the initial increase in S is driven by an increase in the fractionation factor associated with an increase in sulfate concentrations (28). The subsequent decline arises from the input of light sulfur (+7‰) from sulfide oxidation; the S values then rise again as that flux wanes, and finally fall as sulfate concentrations decline once more. Modeled oceanic sulfate levels reach a peak value of 4 mM, which is ∼15% of their modern value.

Incidentally, the pattern of C and S variation argues against two otherwise interesting hypotheses that have been put forth in an effort to account for the Lomagundi Event. The first hypothesis postulates that in response to rising p, methanogenic activity in the shallow marine realm led to the creation of pools of highly 13C enriched carbon, which was then incorporated into Lomagundi-aged carbonates (4). However, under this scenario, carbonate-associated sulfate incorporated during the precipitation of these carbonates should be extremely 34S enriched, in contrast to the moderate values that are observed (27)—although the controls on incorporation of CAS during carbonate precipitation remain incompletely understood. A stronger case can be made against the second hypothesis, that the source of 13C enrichment in Lomagundi-aged carbonates was the burial of 13C-depleted authigenic carbonates in other (unsampled) settings (30). Oxidation of organic carbon via bacterial sulfate reduction during early diagenesis would have led to the precipitation of authigenic carbonates but, at the same time, would have also led to the precipitation of 34S-depleted pyrite, resulting in correlative enrichments in both 13C and 34S in shelf carbonates, in contradiction with the observed inverse correlation.

A key remaining question is the mechanism by which the carbon produced by siderite and pyrite oxidation was directed to organic productivity. Increased carbon input is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for increased organic carbon burial and O2 production. Additional limitations arise from the nutrient requirements of organisms, chiefly phosphate (31). However, a simple increase in weathering and delivery of phosphate to the ocean would not generate a positive excursion, since the resulting increase in organic carbon burial would be coupled to an identical increase in carbonate carbon burial arising from increased delivery of alkalinity. To generate a large positive excursion, the delivery of phosphate from weathering must be decoupled from the delivery of alkalinity to the ocean. Sulfuric acid weathering is a particularly effective way to mobilize P from apatite (18), allowing for increased organic carbon burial without the concomitant delivery of alkalinity that would demand carbonate burial. An additional effective way to supply phosphate for organic productivity is to reduce the output flux of P relative to that of organic carbon. More-efficient remineralization of phosphate allows for the export of more organic carbon per unit phosphate buried. Our model indicates a fivefold increase in C:P ratios through the event (from 106 to 500), which, although large, is still far less than the values found in much younger black shales ( 4,000). The mechanisms by which the C:P burial ratio increased (and by inference, why it was kept low before and after the Lomagundi Event) are still contested (32, 33). We speculate that a combination of the two aforementioned mechanisms may have been at play: Following the initial increase in pO2, oxidation of sulfides allowed for increased P delivery concomitant with increased availability of sulfate. The development of euxinic (-rich) bottom waters (34) facilitated mobilization of phosphate back into the water column. Increased P delivery together with more efficient P utilization allowed for continued organic productivity and organic carbon burial. This mechanism was curtailed following the exhaustion of the siderite reservoir and concomitant drop in sulfate levels (27).

A second key question pertains to the size of the Archean reduced sedimentary reservoirs that were subsequently oxidized. Estimates are uncertain, as they are extrapolated from preserved Archean sedimentary volumes, and thus depend on poorly known parameters such as the areal extent of Archean continents and the geologic history of sediment recycling. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to expect that siderite and sulfide, as well as other reduced crustal minerals, were oxidized following the initial rise of O2. The question of whether the supply of and acidity from these oxidizing species played a pivotal role in driving O2 production hinges critically on the interpretation of the carbon isotopic record. If the highly 13C enriched values are representative of the exogenic carbon pool, and large amounts of organic carbon were buried during the Lomagundi event, then mass balance demands that large amounts of siderite and pyrite were oxidized concurrently to compensate for the enhanced pCO2 drawdown and O2 production.

We conclude by noting that Garrels and Perry (21), in a paper predating much of our understanding of Precambrian redox dynamics, presciently underscored the importance of siderite oxidation in determining the current redox state of the atmosphere: “The role of the oxidation of FeCO3 in creating free oxygen should be emphasized. The level of oxygen in the present steady-state atmosphere would seem to be fortuitous, in that it apparently was controlled by the relative amount of siderite in the preoxygen rocks.” Once the transfer of carbon from the siderite to the organic carbon reservoir was complete, a modern oxidizing atmosphere was established, and Earth settled into its long Mesoproterozoic stasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Kasting, Chester Harman, Ying Cui, and Jeff Havig for valuable comments. We thank Noah Planavsky and an anonymous reviewer for constructive reviews. A.B. thanks the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research for a postdoctoral fellowship given through the Earth Systems Evolution Program. L.R.K. acknowledges support from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Astrobiology Institute, the US National Science Foundation Geobiology and Low-Temperature Geochemistry Program, and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1422319112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kump LR. The rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature. 2008;451(7176):277–278. doi: 10.1038/nature06587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovelock JE, Margulis L. Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the Gaia hypothesis. Tellus. 1974;26:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne JL, et al. Two-phase increase in the maximum size of life over 3.5 billion years reflects biological innovation and environmental opportunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(1):24–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes JM, Waldbauer JR. The carbon cycle and associated redox processes through time. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):931–950. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farquhar J, Bao H, Thiemens M. Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science. 2000;289(5480):756–759. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karhu JA, Holland HD. Carbon isotopes and the rise of atmospheric oxygen. Geology. 1996;24:867–870. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melezhik VA, et al. 2013. The Palaeoproterozoic perturbation of the global carbon cycle: The Lomagundi-Jatuli Isotopic Event. Global Events and the Fennoscandian Arctic Russia - Drilling Early Earth Project, Frontiers in Earth Sciences, eds Melezhik VA, et al. (Springer, Berlin), Vol. 3, pp 1111–1150.

- 8.Schidlowski M, Eichmann R, Junge CE. Carbon isotope geochemistry of the Precambrian Lomagundi carbonate province, Rhodesia. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1976;40:449–455. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin AP, Condon DJ, Prave AR, Lepland A. A review of temporal constraints for the Palaeoproterozoic large, positive carbonate carbon isotope excursion (the Lomagundi–Jatuli Event) Earth Sci Rev. 2013;127:242–261. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aharon P. Redox stratification and anoxia of the early Precambrian oceans: Implications for carbon isotope excursions and oxidation events. Precambrian Res. 2005;137:207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker JC, Hays P, Kasting JF. 1981. A negative feedback mechanism for the long-term stabilization of Earth’s surface temperature. J Geophys Res 86(C10):9776–9782.

- 12.Berner RA, Lasaga AC, Garrels RM. The carbonate-silicate geochemical cycle and its effect on atmospheric carbon dioxide over the past 100 million years. Am J Sci. 1983;283(7):641–683. doi: 10.2475/ajs.284.10.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekker A, Holland H. Oxygen overshoot and recovery during the early Paleoproterozoic. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2012;317:295–304. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres MA, West AJ, Li G. Sulphide oxidation and carbonate dissolution as a source of CO2 over geological timescales. Nature. 2014;507(7492):346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature13030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen B, Buick R. Redox state of the Archean atmosphere: Evidence from detrital heavy minerals in ca. 3250–2750 Ma sandstones from the Pilbara Craton, Australia. Geology. 1999;27:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JE, Gerpheide A, Lamb MP, Fischer WW. O2 constraints from Paleoproterozoic detrital pyrite and uraninite. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2014;126:813–830. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melezhik VA, Fallick AE, Rychanchik DV, Kuznetsov AB. Palaeoproterozoic evaporites in Fennoscandia: Implications for seawater sulphate, the rise of atmospheric oxygen and local amplification of the C excursion. Terra Nova. 2005;17:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konhauser KO, et al. Aerobic bacterial pyrite oxidation and acid rock drainage during the Great Oxidation Event. Nature. 2011;478(7369):369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature10511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohmoto H, Watanabe Y, Kumazawa K. Evidence from massive siderite beds for a CO2-rich atmosphere before approximately 1.8 billion years ago. Nature. 2004;429(6990):395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature02573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veizer J. Secular variations in the composition of sedimentary carbonate rocks, II. Fe, Mn, Ca, Mg, Si and minor constituents. Precambrian Res. 1978;6:381–413. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrels R, Perry E. 1974. Cycling of carbon, sulphur and oxygen through geologic time. Marine Chemistry, The Sea: Ideas and Observations on Progress in the Study of the Seas, ed Goldberg ED (Wiley, New York) Vol 5, pp 303–336.

- 22.Partin CA, et al. Large-scale fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels from the record of U in shales. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2013;369-370:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuschel M, et al. Isotopic evidence for a sizeable seawater sulfate reservoir at 2.1 Ga. Precambrian Res. 2012;192:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasting JF. What caused the rise of atmospheric O2? Chem Geol. 2013;362:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen B, Krapež B, Meier DB. Replacement origin for hematite in 2.5 Ga banded iron formation: Evidence for postdepositional oxidation of iron-bearing minerals. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2014;126:438–446. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kump LR, Seyfried WE., Jr Hydrothermal Fe fluxes during the Precambrian: Effect of low oceanic sulfate concentrations and low hydrostatic pressure on the composition of black smokers. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2005;235:654–662. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Planavsky NJ, Bekker A, Hofmann A, Owens JD, Lyons TW. Sulfur record of rising and falling marine oxygen and sulfate levels during the Lomagundi Event. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(45):18300–18305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120387109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habicht KS, Gade M, Thamdrup B, Berg P, Canfield DE. Calibration of sulfate levels in the Archean ocean. Science. 2002;298(5602):2372–2374. doi: 10.1126/science.1078265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canfield DE, Farquhar J. Animal evolution, bioturbation, and the sulfate concentration of the oceans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(20):8123–8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902037106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrag DP, Higgins JA, Macdonald FA, Johnston DT. Authigenic carbonate and the history of the global carbon cycle. Science. 2013;339(6119):540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1229578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laakso TA, Schrag DP. Regulation of atmospheric oxygen during the Proterozoic. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2014;388:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjerrum CJ, Canfield DE. Ocean productivity before about 1.9 Gyr ago limited by phosphorus adsorption onto iron oxides. Nature. 2002;417(6885):159–162. doi: 10.1038/417159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konhauser KO, Lalonde SV, Amskold L, Holland HD. Was there really an Archean phosphate crisis? Science. 2007;315(5816):1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1136328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhard CT, Raiswell R, Scott C, Anbar AD, Lyons TW. A late Archean sulfidic sea stimulated by early oxidative weathering of the continents. Science. 2009;326(5953):713–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1176711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons TW, Reinhard CT, Planavsky NJ. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature. 2014;506(7488):307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature13068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.