Abstract

Background: In recent years, accreditation of private hospitals followed by decentralisation of the Italian National Health Service (NHS) into 21 regional health systems has provided a good empirical ground for investigating the Tiebout principle of "voting with their feet". We examine the infra-regional trade-off between greater patient choice (due to an increase in hospital services supply) and financial equilibrium, and we relate it to the significant phenomenon of Cross-Border Mobility (CBM) between Italian regions. Focusing on the rules supervising the financial agreements between regional authorities and providers of hospital care, we find incentives for private accredited providers in attracting patient inflows.

Methods: The analysis is undertaken from an institutional, regulatory and empirical perspective. We select a sample of five regions with higher positive CBM balance and we examine regional regulations governing the contractual agreements between purchasers and providers of hospital care. According to this sample, we provide a statistical analysis of CBM and apply a Regional Attraction Ability Index (RAAI), aimed at testing patient preferences for private/public accredited providers.

Results: We find that this index is systematically higher for private providers, both in the case of distance/boundary patients and of excellence/general hospitals.

Conclusion: Conclusions address both financial issues regarding the coverage of regional healthcare systems and equity issues on patient healthcare access. They also raise concerns on the new European Union (EU) directive inherent to patient mobility across Europe.

Keywords: Patient Mobility, Italian National Health Service (NHS), Hospitals’ Accreditation, Regional Strategies, Patient Choice

Introduction

In Italy, hospital accreditation – either in the private or public sector – has been carried out with the objective of implementing competition mechanisms among providers, improving the quality of care and containing the health expenditure. Patient free choice is the appropriate tool for enhancing these goals. However, as different authors suggest, competition does not necessarily lead to positive effects in the healthcare sector as results depend to a considerable extent upon the rules of the system (1–4). In Italy, the “rules of the system” are the following: the National Health Service (NHS) is set on a federal model where each region is responsible for the organisation and funding of the local health system. Patients do not have to pay for hospital treatments and can choose their healthcare providers according to their preferences, inside or outside their region of residence. However, if they choose a private provider, this has to be accredited by the health system of the region in which it is established in order to be free of charge. The accreditation process in Italy has been implemented without a uniform design: some regions, mostly the ones located in northern or central Italy, have accredited (among others) well-provided hospitals, whereas very few southern regions (including Molise) did the same (5,6). As a consequence, there is a consistent annual flow of patients migrating from southern regions towards central-northern ones in search of hospital admissions: this phenomenon is significant, since 34.2% of total Cross-Border Mobility (CBM) moves in this direction, causing a considerable financial impact on regional budgets (6–10). We aim to investigate whether the regional rules governing financial coverage of hospital admissions might have been used as an incentive to private providers in order to attract patients from other regions. Private accredited hospitals are more used to marketing initiatives in order to attract patients, compared to public hospitals: while the risk of bailing out for the former is real, public hospitals have benefited from ex-post refunding by regions for many years. Therefore, in the case of excess production, patient inflows could represent a valid source of revenue for private providers.

From the demand side (according to most authors), the main determinants of patient choice in opting for a determined hospital are perceived quality of services (influenced by the availability of information on hospital performance), distance from the hospital and waiting times (11–13). Gravity models are frequently used to explain patient mobility across regions or Health Districts (HD). In very general terms, a patient will choose a hospital in region A, with respect to a hospital in region B where he lives, if the cost of moving offsets the difference in quality between the two hospitals. To this extent, of course, the availability of services in both regions is an important variable to be considered (14). The higher the difference in quality between region A and region B and the lower the travel costs, the higher the probability of observing a migration between A and B (11). There is a range of variables employed in gravity models to explain patient mobility across regions or HD, including population density at HD origin/destination, per capita income at HD origin/destination, technology index at HD origin/destination and availability of at least a Hospital Trust in the HD of destination, in order to indicate the presence of a well-provided hospital able to attract patient inflows (13). With regard to the previous issue, hospital accreditation policies between 1992 and 1999 – including the choice of accrediting well-provided hospitals –have been autonomously implemented by each region within the context of the Italian federal setting.

We want to test whether, besides the well-known determinants of patient CBM, there is an induction effect that applies to accredited private providers and is encouraged by the internal rules of selected regions attracting consistent patient inflows1. Reliable CBM flows may prove beneficial at a regional level for different reasons, such as absorbing any excess production in the hospital sector, balancing the regional healthcare budget (10), increasing the use of local services (accommodations, restaurant and tourist facilities) and improving the perception of quality within a region, which means a good electoral feedback for regional authorities. We focus on the possible strategic incentives applied to accredited private providers at regional level in order to attract CBM flows. Some northern and central regions might have accredited new providers not only to meet region-wide hospital care requirements, but also with the aim of attracting patient inflows from other regions (particularly from southern Italy), where hospitals do not cover such a broad range of treatments and/or do not guarantee the same perceived quality of care. The geographical factor is significant in this context. In 2011, southern regions reported a negative balance amounting to €-1.046 billion for CBM, while northern regions reported a surplus of €863 million (9). Within this framework, the “money follows the patient” principle is strictly complied with. The result is that southern regions pay for both their internal inefficiencies (hospitals not reaching economies of scale) and their patients’ escape (for whom they have to pay the entire cost of treatment); whereas northern regions benefit from good quality hospital systems that meet economies of scale, facing a small degree of outflows due to passive mobility – therefore balancing their budgets. Actually, patient mobility is somehow unavoidable since, when dealing with very rare treatments, it is efficient to concentrate the supply in few hospital centres (15). Apart from these cases, we consider the patient’s decision to move to another region as both a manifestation of his/her dissatisfaction with the local healthcare supply (13) and successful marketing initiatives by private providers in the region of destination. We consider accreditation – and especially the rules supervising financial agreements between regional authorities and providers of hospital care – as a possible determinant factor for CBM in the Italian NHS.

Patient mobility is not a phenomenon that is limited to the Italian case. Evidence exists regarding CBM within the NHS in the UK (16) and also in the Spanish decentralised health service (12). Actually, most of the recent literature on patient mobility relates to international mobility between countries, in some cases even labelled as “medical tourism”. This increasing phenomenon has been studied under different perspectives – flow size, internal domestic regulations, reciprocity agreements between countries, patient profiles and equity concerns – but further research on this topic is still needed (14,17–20). However these issues – despite a possible parallelism with Italian inter-regional mobility – go beyond the scope of this study: namely the relation between accreditation policies at the regional level and the CBM phenomenon.

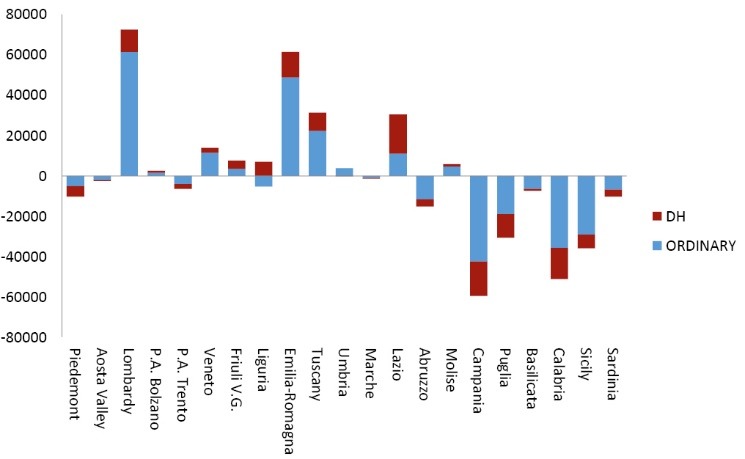

The Italian case is appealing from a policy perspective due to the decentralisation of its NHS in 21 different regional health systems which, together with patient free choice, offers a good empirical ground for investigating the Tiebout principle of “voting with their feet” (21). The analysis is undertaken from an institutional, regulatory and empirical perspective. With this in mind, we have selected a sample of regions deemed significant in terms of positive CBM balance (see Figure 1) and representative of different regional healthcare models. The selected regions are Lombardy (quasi market model) and Emilia Romagna (integrated model) in the North, Tuscany (prevalence of public beds) and Lazio (prevalence of private beds) in the Centre, and Molise – the only southern region showing a positive balance for hospital CBM – in the South (5,22). The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Institutional background section presents the institutional framework governing provision of hospital services in Italy’s NHS; The next section analyses the normative framework regulating the hospital accreditation process both at a national and at a regional level, as well as contractual agreements between purchasers and providers of hospital care services; Methods section describes the relevant data and the statistical analysis; Discussion section summarises the main findings; while Conclusions section address a few policy proposals suitable for regulating the CBM phenomenon in the hospital sector that involves nearly 810,000 patients on a yearly basis (8,9).

Figure 1 .

CBM balance for acute admissions (ordinary and DH) – year 2011. Source: Elaboration of data from the Ministry of Health (MoH).

Institutional background

The reform of the Italian NHS, which started in 1992 and was finalized in 1999, introduced competition principles among providers with the twofold objective of increasing the quality of care and containing the healthcare expenditure (23–25). The main features of the theoretical model are the separation between purchaser and provider, with competing providers, centrally set prospective prices [Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) tariffs], the provision of greater and more accessible information on quality and the encouragement of entry, mainly from the private sector.

Subsequent to the reform, the hospital sector underwent a radical change: many private providers were accredited and, similarly to public hospitals, they were granted public funds for hospital activities delivered within the NHS scheme. In Italy, patients are provided with hospital treatment completely free of charge. Each region, through its Local Health Authorities (LHAs), is financially responsible for the health services delivered to its resident population. Accredited private hospitals have the option of treating patients within the NHS scheme (i.e. free of charge) and be reimbursed by the LHA that the patient belongs to (13). Healthcare funds are distributed by the regions to the LHAs based upon (possibly adjusted) capitation arrangements. At the beginning of the year, each LHA allocates a share of its budget for hospital activity: hospital treatments can be provided by independent public hospitals (i.e. Hospital Trusts, bearing full responsibility for their own budgets), accredited private hospitals, or public hospitals directly managed by the LHA. With the first two categories of providers, the purchaser (LHA) contracts the number and typology of admissions as well as the restrictions (overall ceiling, tariff caps and cuts) in case of excess production. Admissions are paid on a DRG scheme. If hospital treatments are sold to non-enrolled persons, LHAs receive additional resources for the treatments they export. Similarly, LHAs paying for the treatments they import (i.e. for the admission of their patients in a hospital which is not in their territory) will suffer from financial outflows (13).

This framework can be transposed on a larger scale at an inter-regional level, where sizeable financial flows subsidize patient mobility across regions. Italy implemented its fiscal federalism in 2000. Each region, through its internal taxation, raises the funds needed to finance its healthcare sector. In compliance with the patient free choice principle, individuals are allowed to choose the provider of their hospital care without any geographical constraint, whether inside or outside their region of residence. In the latter case, however, this gives rise to a financial transaction respectively between regions of residence and destination, through a conventional flat rate Tariffa Unica Convenzionale (TUC). TUC is DRG-specific and henceforth includes the full cost (running and fixed2) for treatment: since tariffs related to the same treatment (e.g. tonsillectomy) may vary between regions, the TUC is a “mean of regional DRGs” due to a specific treatment. To this extent, regions experiencing high patient outflows end up paying for both the hospital treatment supplied to their outgoing patients and the fixed costs of their public hospitals that cannot work efficiently due to a low demand for admissions. From a financial standpoint, each region has a strong incentive to limit its outflow of patients and to attract inflows of patients from other regions. In a federal setting, as is the case in Italy, it becomes crucial to find out whether the regions showing high patient inflows developed their accreditation process primarily to meet their internal care requirements, or essentially with the indirect objective of attracting CBM. Most of the regions showing a positive CBM balance transformed their deficits into net gains through CBM revenues (10).

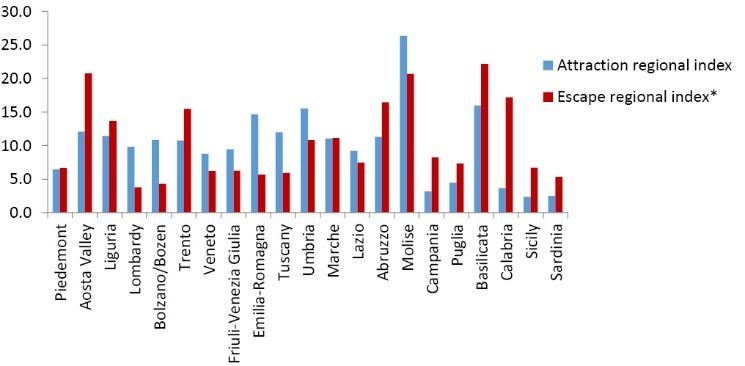

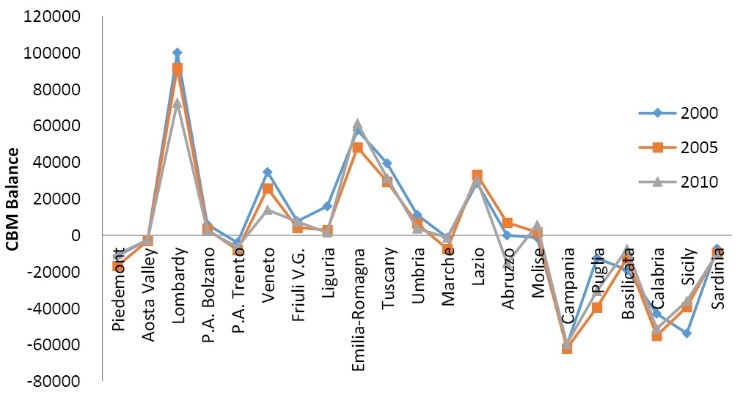

This analysis focuses on admissions in acute care, which represent almost 80% of the entire CBM phenomenon in terms of volume and financial flow. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a clear geographical factor, with the southern regions showing high escape values and most of the northern and central regions presenting marked attraction values. When observing the longitudinal CBM balance data (2000-2005-2010), the stability of the trend suggests the presence of a structural misallocation of resources in the Italian NHS (Figure 3).

Figure 2 .

Attraction and escape regional index – acute admissions (ordinary and DH) – year 2011. Source: Elaboration of data from the MoH. * Escape and attraction indeces are expressed in percentage values.

Figure 3 .

Trend of CBM balance – years 2000, 2005, 2010. Source: Elaboration of data from the MoH.

The accreditation process between centrally set rules and regional regulations

In Italy, the hospital accreditation process began in 1992 with Decree no. 502/92, which established the qualitative standards of providers in order to implement a new healthcare system where public and private hospitals would compete for the provision of healthcare. The objectives were competition increase, health expenditure control and a better quality of care. After a few years of minor changes in the regulations, the reform was finalized in 1999 (Decree no. 229/99), with the definition of a four-step accreditation process. This procedure, also called the “four A” system, is organized as follows: 1) authorization to build the hospital facility; 2) authorization to carry out healthcare activities; 3) institutional accreditation; 4) contractual agreements. While the first two steps are mostly related to technical aspects, the other two quite closely reflect the health policy approach of each region and, therefore, require some comments. Institutional accreditation is the stage that gives the provider permission to work for the Italian NHS, and it is only granted subsequent to prior authorization by the region, consistently with internal hospital care needs and resource planning. This step has been performed autonomously at a regional level, without central supervision guaranteeing an equitable allocation of hospital services among regions. Some regional health systems have accredited well-provided hospitals, while others have not, and this picture follows a north-south gradient. The reason for this heterogeneity can possibly be found in the “two-speed” regionalisation process that applies to the Italian case [see for example (26)]. From the nineties on, in view of an imminent decentralisation, several northern and some central regions worked on reinforcing their own healthcare systems, while most of the southern regions did not have a clear plan on how to develop their health service supply (5). The Italian north-south gradient is deeply rooted in historical cultural and political factors: although steps have been taken towards filling many gaps over the last decade, differences still remain and the regional autonomy shown in several northern healthcare systems is still far from being achieved in the southern regions.

The final step – the contractual agreement – is the tool that grants public funds to accredited private hospitals: without this agreement, a private provider can still admit NHS patients, but only on a “private funding” basis. At the beginning of the year, every LHA charts out, through a contractual agreement with each provider, the type and maximum number of admissions (overall ceilings), as well as the financial restrictions applied (tariff caps or cuts). In general terms – and this is a very important issue for our analysis – it is more likely for private providers to comply with these restrictions: when public providers exceed their upper production limit, they are actually refunded ex-post by the region for any budget loss. Fortunately, in recent years, the risk of bailing out by public providers has been kept under control and in many regions public providers comply to ceilings and targets. However, when it applies, this condition raises an important equity question because it represents additional funding for public health centres that is denied to private hospitals (27–29). This consideration led us to a closer investigation, within the selected sample of regions, of the regulations governing contractual agreements: evidence shows that a more extensive entrepreneurial autonomy is granted to accredited private hospitals, which often balance their budget by drawing resources from CBM flows. The regional legislation of all regions included in the sample, with the exception of Molise3, shows that LHAs and regions determine with private providers the maximum number of admissions (ceilings) just for resident patients, contextually excluding cross-border patients from any kind of restriction. For example, this is the case for Lombardy and Emilia Romagna, where the financing of CBM admissions is paid extra-budget at the end of the year. In the General Agreement between the Emilia Romagna Region and Italian Association of Private Accredited Hospitals (AIOP) we found that: “The payment of the cross-border admissions is not accounted for in the budget, nor is the access of non-resident patients subject to restrictions by the LHAs of Emilia Romagna...”. This condition implicitly recognises diverse entrepreneurial authority to private providers, who are regulated by a different contractual scheme compared to public providers. Based on this mechanism, a production excess by accredited private providers can relapse financially on patient inflows.

Methods

Analysis of Cross-Border Mobility (CBM) flows

The empirical analysis focuses on CBM acute admissions for the five regions included in the sample: Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, Lazio and Molise. We only take publicly financed admissions into consideration, i.e. CBM patients hospitalised in public and private hospitals under the NHS scheme. The data, updated to 2010, has been directly provided to us following our request by the Ministry of Health (MoH) and this yields an additional value to the analysis: namely the chance to disaggregate patient inflows according to the typology of the selected hospital, information that is not available on the Ministry’s website [see, for example (13)]. The heterogeneity of the Italian hospital supply – by typology, legal ownership and degree of autonomy – requires a brief description. Considering the public providers, Public Hospital Trusts are independent public hospitals controlled by a General Manager who is appointed by the region. They are separated from the LHA with whom they contract the volume and typology of admissions. On the contrary, more limited autonomy is given to the LHA hospitals, because they are run directly by the LHAs. University Hospitals and IRCCSs (Treatment and Research Institutes) are for the most part (both public and private) teaching facilities or hospitals carrying on research activities, for which they receive extra government funds. The MoH considers Istituti di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCSs) as centres of excellence (22). Considering the organisational structure, the size (average number of beds in acute care), the complexity of services being provided and (mainly) research activities, we place them in the same category as University Hospitals. The private hospital category also includes: i) religious hospitals, almost all of them classified as non-profit institutions; ii) private for-profit hospitals (namely, private clinics); iii) hospital centres belonging to the LHAs but temporarily managed by private foundations via public-private partnerships (LHAs presidia); and iv) private “Research Unit Hospitals”, which are hospitals devoted for the most part to research activities. We maintain this classification in our analysis on mobility flows, focusing on the private/public differentiation. The disaggregation of mobility flows according to different hospital categories helps us in focusing on the preferences toward the public or private sector, controlling for the category of hospital chosen. One must bear in mind that patients move from one region to another because of a significant gap in the perceived quality of care. Within a framework of incomplete information (which is typical of the healthcare sector), the perceived quality of care can be easily influenced by the supply side, especially when the single hospital is offered incentives for attracting mobility. We have reported that the regions within the sample provide financial incentives to private accredited hospitals in order to attract patient inflows; there is evidence that some major private hospitals in the northern regions do informally promote their services in southern Italy and recruit patients through local specialists (6). This evidence supports our hypothesis of a more developed entrepreneurial activity by private providers, who react to budget restrictions by attracting non-resident patients (whose admissions are paid extra budget).

Our suggestion is that the CBM patient preferences can easily be influenced when information on hospital quality is incomplete, and regional regulations can make the most of this evidence in order to obtain opportunistic advantages.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed considering the regions of origin/destination of the CBM flows. The two factors to be controlled for are: i) the type of mobility (boundary versus distance mobility) and ii) the type of destination (when hospitals of excellence are preferred, we can detect a “quality search” mobility). According to literature, “boundary CBM” is due to territorial proximity and to a certain extent is to be considered structural; whereas “distance CBM” is more quality-oriented (6,11–13). The statistical investigation was carried out using specific parameters. The most common indicators applied by scholars to the analysis of CBM are the “attraction index” and the “escape index”. The former is the ratio between the cross-border admissions and total discharges within the region. It indicates, for each region, the percentage of external applications for admission (from all the other regions) over total annual admissions. The “escape index” of any region is the ratio between the number of individuals leaving their region of residence in order to be hospitalized elsewhere in Italy, and the total number (in- and outside the region) of resident patient admissions. It reveals the dissatisfaction of patients for their own region. Both parameters are good for measuring CBM flows across regions from a national perspective. However, for our own purposes, we needed to find a more specific indicator allowing us to analyse CBM flows among selected regions. Given the vector X = x1...x21 for the 21 Italian regions and the vector Y = y1...y5 for the five sample regions, we built a “Regional Attraction Ability Index” (RAAI) which is given by the ratio of “patients coming from xi, (with i = 1,21 ) and admitted in yj (with j = 1,5) and “the total amount of passive CBM for xi”. The newly found parameter measures for each region xi “the percentage of resident patients in mobility who choose to be admitted in the region yj of the sample”. So, in a way, it measures the power of attraction of yj over xi.

With RAAIyj/xi = index of the ability of a sample region (yj) to attract patients from another specific region (xi); PCBMxi/yj = number of patients resident in region xi and admitted to hospitals in region yj;

Tot PCBM xi = total number of patients resident in region xi being admitted to hospitals in other regions (i.e. passive CBM of region xi).

We used the RAAI index only during the first step of the analysis and applied it to each region yj of the sample – namely Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, Lazio and Molise – in order to select the three boundary regions x1…x3 and the three distance regions x4…x6, which export the highest percentage of their residents to that region yj. This step is represented in Table 1, using Lombardy as an example4. After that we built, in respect of each sample region, a matrix table matching the flows of patients, from each previously selected region x1…x6 with the different categories of hospitals admitting them. In this second step of the analysis, we applied the attraction index formula to each hospital category: namely we matched each hospital category of the region yj of destination with the number of patients coming from each one of the six selected regions x1…x6. This would give us some cross information between the kind of mobility (boundary and distance) and the kind of hospital chosen (whether public or private/excellence or not). The attraction index computed for each hospital category (Attraction Index Hospital Category) is given by a fraction. The numerator shows the number of patients coming from a selected boundary or distance region (x1…x6) and admitted to a selected category of hospitals (e.g. Public Hospital Trust); the denominator shows the yearly number of admissions to that specific category of hospitals. These values allowed us to compare boundary and distance CBM using a parameter which is weighted for the total number of patients admitted to each hospital category. Thus, the number of beds supplied within that category should not be an issue. The matrix tables, set up for each sample region, provided us with information respectively about “boundary” and “distance” patient choice, disaggregated by type of provider.

Table 1 . Lombardy, RAAI (acute admissions) - year 2010 .

| Hospital CBM - RAAI Lombardy- year 2010 | ||

| Resident region | No. of CBM patients admitted in Lombardy | RAAI (%) |

| Piedmont -B- | 25,384 | 77.4 |

| Valle d'Aosta | 705 | 19.9 |

| Lombardy | - | 0.0 |

| P.A. Bolzano | 480 | 16.5 |

| P.A. Trento | 1,902 | 21.4 |

| Veneto | 9,404 | 31.6 |

| Friuli V.G. | 1,547 | 17.6 |

| Liguria -B- | 8,526 | 33.6 |

| Emilia Romagna -B- | 18,300 | 60.6 |

| Toscana | 6,161 | 24.2 |

| Umbria | 1,072 | 8.3 |

| Marche | 2,787 | 13.4 |

| Lazio | 4,748 | 10.4 |

| Abruzzi | 2,147 | 7.7 |

| Molise | 536 | 6.2 |

| Campania | 8,288 | 14.1 |

| Puglia -D- | 9,877 | 23.8 |

| Basilicata | 1,631 | 10.5 |

| Calabria | 9,604 | 23.0 |

| Sicily -D- | 15,257 | 38.9 |

| Sardinia -D- | 4,602 | 42.9 |

| Total | 132,958 | 24.8 |

CBM= Cross-Border Mobility; RAAI= Regional attraction ability index; B= Boundary; D= Distance.

Source: Elaboration of data from the MoH.

Results

With reference to each region of the sample, the results show – as we expected – that the attraction power is on average higher for boundary regions. Disaggregating these figures by hospital category, the centres of excellence show on average the highest attraction indices, confirming, as literature suggest, that quality is a mobility driving factor for both boundary and distance CBM. The hypotheses suggested by literature on both gravity models and the presence of a quality driven mobility are indirectly confirmed by our analysis.

But most importantly, with reference to each region of the sample and every hospital category, our findings demonstrate an attraction index that is systematically higher for accredited private hospitals than for public hospitals; this applies to both distance/boundary choices and every hospital category. These results (i.e. patient inflows demonstrating a significant preference for private accredited hospitals) are corroborated by a recent study on the Italian CBM, which is restricted to the field of aortic valve replacement (6).

Tables 2 and 3 report the values for Lombardy and Tuscany, respectively. For Lombardy, the aggregated attraction index for the private hospital category (15.9%) compared with that of public providers (5.9%) indicates a greater ability of the private sector in intercepting the non-resident demand. It is interesting to observe that, although the number of beds of public providers (23,489) is much higher than that of private providers (13,924), the number of admissions in 2010 is almost the same for the two categories (66,808 public versus 66,150 private). Focusing on hospitals of excellence (which show the highest attraction index), there is a greater degree of preference for private hospitals (25.4% private vs. 16.1% public); this finding suggests the presence of possible strategic incentives from the supply side that influence the choice of patients. In the case of the Lombardy region, the highest attraction index is the one for private centres of excellence (25.4%). The disparity between public and private attraction indices remains when considering each of the six regions (Piedmont, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Puglia, Sicily and Sardinia) that contribute with a higher degree of patient inflows to Lombardy (columns 10 and 11 of Table 2). Specifically, both distance and boundary flows show a greater preference for private providers and, on average, the highest attraction indices relate to boundary CBM. This result could mean that the induction from private providers has a greater impact on boundary mobility, where patient preferences are not constrained by travel/accommodation expenses. However, this item needs to be investigated to a greater extent.

Table 2 . Lombardy, Disaggregation of CBM acute admissions by category of hospitals (public/private) and kind of mobility (boundary/distance) – year 2010 .

| Public hospital Trusts | LHA's hospitals | Public centers of excellence a | Private centers of excellence a |

Non-profit

religious |

Private clinics | LHA's private presidia | Research unit hospitals | Total Public | Total Private | Total | |

| Number of beds (2009) | 20,904 | 311 | 2,274 | 4497 | 1,251 | 8,006 | 170 | - | 23,489 | 13,924 | 37,413 |

| Attraction index | 4.5% | 1.1% | 16.1% | 25.4% | 3.7% | 9.7% | - | - | 5.9% | 14.8% | 8.4% |

| Positive CBM acute admissions | 44,486 | 131 | 22,191 | 41,181 | 1,626 | 23,343 | - | - | 66,808 | 66,150 | 132,958 |

|

Attraction index Piedmont -Bb |

0.9% | 0.1% | 3.3% | 5.0% | 0.9% | 1.6% | - | - | 1.1% | 2.7% | 1.6% |

|

Attraction index Veneto -B |

0.4% | 0.1% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.2% | 1.2% | - | - | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.6% |

|

Attraction index Emilia Romagna -B |

0.8% | 0.1% | 1.7% | 2.3% | 0.2% | 1.9% | - | - | 0.9% | 1.9% | 1.2% |

|

Attraction index Puglia -Db |

0.3% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 2.1% | 0.4% | 0.4% | - | - | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.6% |

|

Attraction index Sicily -D |

0.5% | 0.1% | 2.0% | 2.9% | 0.5% | 1.0% | - | - | 0.7% | 1.6% | 1.0% |

|

Attraction index Sardinia -D |

0.1% | 0.1% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.2% | 0.4% | - | - | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

LHA= Local Health Authoritie; CBM= Cross-Border Mobility.

aUniversity hospitals and IRCCS.

b B= boundary regions; D= distance regions.

Source: Elaboration of data provided by the MoH.

Table 3 . Tuscany, disaggregation of CBM acute admissions by category of hospitals (public/private) – year 2010 .

| Public hospital firms | LHA's hospitals | Public centers of excellence a | Private centers of excellence a | Non-profit religious | Private clinics | LHA's private presidia | Research unit hospitals | Total Public | Total Private | Total | |

| Number of beds (2009) | - | 6,460 | 3,124 | 70 | - | 1,776 | 155 | 117 | 9,584 | 2,118 | 11,702 |

| Attraction index | - | 4.5% | 16.5% | 60.8% | - | 32.7% | - | 0 | 9.1% | 31.9% | 11.1% |

| Positive CBM - acute admissions | - | 15,898 | 35,471 | 1,210 | - | 15,301 | - | 800 | 51,369 | 17,311 | 68,680 |

|

Attraction index Liguria -Bb |

- | 1.1% | 1.4% | 8.1% | - | 7.6% | - | 0 | 1.2% | 7.6% | 1.8% |

|

Attraction index Umbria -B |

- | 0.5% | 1.1% | 3.9% | - | 4.0% | - | 0 | 0.7% | 3.6% | 1.0% |

|

Attraction index Lazio -B |

- | 0.7% | 2.2% | 2.3% | - | 5.8% | - | 0 | 1.3% | 5.2% | 1.6% |

|

Attraction index Campania -Db |

- | 0.3% | 2.8% | 12.5% | - | 2.3% | - | 0 | 1.3% | 2.5% | 1.4% |

|

Attraction index Sicily -D |

- | 0.3% | 1.6% | 5.3% | - | 2.2% | - | 0 | 0.8% | 2.1% | 0.9% |

|

Attraction index Sardinia -D |

- | 0.1% | 0.4% | 1.9% | - | 0.3% | - | 0 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

LHA= Local Health Authoritie; CBM= Cross-Border Mobility.

aUniversity hospitals and IRCCS.

b B= boundary regions; D= distance regions.

Source: Elaboration of data provided by the MoH.

With respect to Tuscany, results confirm an aggregated attraction index that is higher for the private hospital category (31.9%) than for the public providers one (9.1%). Hospitals that are centres of excellence still demonstrate very high attraction indices and, again, the disparity between the power of attraction of private and public hospitals is shown for each one of the x1…x6 (boundaries and distance) regions. Private clinics, whose presence is widespread on the territory, also show a very high attraction power, highlighting how the internal structure of each regional health system could influence CBM flows. As for Lombardy, attraction indices in the category of private providers are higher for boundary regions compared to distance regions on an average.

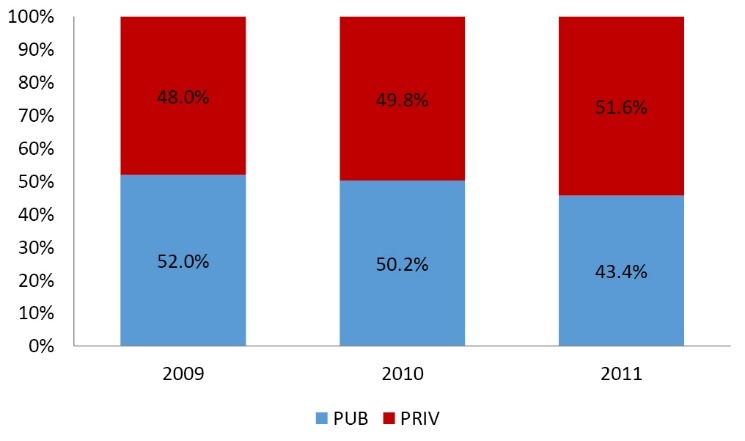

Data on the other sample regions are reported in the Additional file 1 and the results are aligned with those of Tuscany and Lombardy. In general, with reference to all the sample regions, the greater power of attraction exercised by private hospitals with respect to public ones is confirmed for both boundary and distance CBM. This finding is corroborated by the CBM trend during the last three years of observation (2009-11) that shows a progressive increase in the number of CBM patients admitted to accredited private hospitals for each region in the sample, with the exception of Molise (see Figure 4 for Lombardy). The case of Molise, the only southern region with a positive CBM balance (3,075 in 2010), is enlightening. Molise is one of the smallest regions in Italy with 319,780 inhabitants, ten hospitals, 1,425 beds and 71,248 admissions in acute care over the year 2010. Nonetheless, one patient out of four comes from another region. The highest values of regional attraction ability indices are shown for Campania (15%), Puglia (8.1%), Abruzzi (8.1%) and Lazio (6.6%), which are all boundary regions. Molise attraction ability is almost entirely due to the presence of two centres of excellence: “IRCCS Neuromed”, specialised in neurological pathologies (with an 82.5% attraction index); and “Biomedical Science” Academic Research Unit, both of which are private facilities. This result stresses the importance of an accreditation policy designed to increase the quality of a regional health system and confirms that well-provided hospitals and private entrepreneurship are two driving factors for mobility. While some northern and central regions have developed their accreditation process opting for improvement in the quality of their regional health systems, many southern regions failed to do so [to this extent, see (5)], with the consequence that consistent flows of patients (and money) migrate every year from the south to those northern and central regions in order to obtain hospital care. Our analysis suggests that the infra-regional trade-off between greater patient choice (due to an increase in hospital services supply) and financial equilibrium has been solved by many regions (typically those showing higher CBM balance) by driving patient inflows. The arrangement of ad hoc contractual agreements between regional authorities and the accredited private providers category in order to favour non-resident patient admissions, corroborates this hypothesis [see for example the 2011–4 General Agreement between the Emilia Romagna Region and the Association of Private Accredited Hospitals; and, for Lombardy, Decree no. 2693/2011 and (29)]. When patient inflows are prevalently steered towards accredited private providers, this phenomenon depends upon the ability of the latter to induce the demand; moreover, it is based on incentives resulting from the contractual agreements between purchasers and providers of hospital care. A few northern and central regions might have furthered the accreditation of private centres of excellence, with the dual objective of developing high-quality regional health systems and exporting any excess production to other regions.

Figure 4 .

Lombardy: CBM acute admissions (ordinary and DH) by typology of hospital ‑ years 2009–11. Source: Elaboration of data from the MoH.

This fact, however, exacerbates the north-south gradient in the Italian NHS. The presence of reliable one-way flows of patients leaving their own regions to seek care elsewhere is due to a misallocation of resources in the Italian NHS caused, inter alia, by the lack of centralized planning during the accreditation process. Federalism did not help this picture. The perception of the quality of care provided by a region depends upon the ability of that region to export net flows of services. Some regional health systems, such as those belonging to Lombardy and Emilia Romagna, reaped the greatest advantages from CBM. While the CBM phenomenon could be explained and accepted in a few cases by the presence of specialisations, this becomes an issue when it involves a one-way flow of patients accompanied by financial resources. This unilateral flow, as Tiebout suggests, is very good at representing the inefficiencies of the regional health systems in the south; systems that are not able to retain their own patients and which simultaneously pay for the fixed costs of their hospitals and for the migration of their patients to facilities in other regions. To this extent, due consideration should be given to equity issues related to the possibility of individual patient to move to another region, given high travel and accommodation expenses [see (6) in this respect].

Discussion

The aim of the paper was investigating whether CBM patients actually prefer private accredited hospitals rather than public hospitals. The normative inspection of the rules supervising financial agreements between regional authorities and providers of hospital care, within the regions showing very high inpatient flows, suggests the presence of strategic incentives able to drive patient inflows towards private hospitals. The accreditation of private hospitals in some regions was carried out with the two-fold objective of implementing a good quality health system and contextually overcoming the risk of an excess production by drawing financial resources from CBM flows. The analysis was structured in three phases: i) an inspection of the institutional framework ruling the hospital accreditation process at a central level; ii) a more specific insight – within a selected sample of five regions – into the regional regulations governing contractual agreements between purchasers and providers of hospital care; and, finally, iii) an empirical investigation of CBM flows directed towards the five regions of the sample, in order to test for patient preferences. A common denominator of the five selected sample regions is their high positive CBM balance, while they diverge with respect to the inner setting of their healthcare systems. The latter feature has been chosen in order to detect every possible aspect of CBM flows due to the regional supply of hospital services, principally focussing on the disaggregation between public and private hospitals and between hospitals that are or are not centres of excellence. The first phase has highlighted the implicit contradiction of an accreditation system that, originally set down by the central government, has been formally developed at a regional level with a fair margin of autonomy. As suggested by literature, an increased supply of hospital services within a publicly financed sector – given fixed tariffs – inevitably clashes with the budget constraints determined at a regional level (3,30). To this extent, the internal regulations enforced by each region for planning the maximum amount of production and the reimbursement limits for hospital care providers becomes crucial. It is more likely that private hospitals respect production ceilings more strictly than public hospitals, because the latter can be refunded ex-post by regional authorities. In consequence thereof, private providers of hospital care are allowed (and even encouraged by contractual agreements) to make up for their excess production through CBM flows. Our regulatory assessment of the contractual agreements between purchaser and providers of hospital care shows that it is only in respect of private providers that CBM admissions are excluded from the production limits set on a yearly basis and are paid extra-budget at the end of the year. This is true for all the regions of the sample, except for the small-sized Molise region, where the geographical location and the presence of two high-quality accredited private hospitals suggests that CBM in this region is guaranteed without the need for regulatory-type incentives. The empirical inspection confirms our findings and demonstrates that the attraction indices of private providers of hospital care – disaggregated by homogeneous categories – are higher compared to those of public providers. As a further finding, in four regions out of five there is evidence of higher weighted flows of CBM towards facilities of excellence (IRCCS and University Hospitals) compared to the other providers; suggesting that these facilities represent an attraction pole for non-resident patients. Still, a higher preference for the private sector is detected within this category.

Concluding remarks and policy proposals

Inter-regional mobility for hospital care is becoming a predominant issue for resource reallocation among regions. Our analysis shows a considerable constant flow of patients (and money) moving from the south of Italy (especially from Calabria, Campania, Puglia and Sicily) towards selected regions in central and northern Italy, where more effective and entrepreneurial providers may take advantage of this migration in order to increase their business. This phenomenon raises concerns at both a micro and a macro level. At a micro level, patients migrate when the perceived quality of care in another region offsets the costs of migrating; but given the high costs of moving to a distant region, free choice is actually limited by the resources available to the patient and this point raises equity issues (31). At a macro level, besides the denied right of equal access to equal care (which is a basic principle of the Italian NHS), there is an annual flow of resources going from the southern to the central/northern areas of the country. To this extent, regions experiencing high patients outflows pay for both hospital treatments supplied to their outgoing patients and fixed costs of their public hospitals, which suffer from a low demand for admissions. This gives rise to a dual policy proposal. Firstly, as far as southern Italy is concerned, new investments in personnel, advanced technology and specialization within the hospital sector would help contain patient outflows – as suggested by the Molise experience. Contextually, southern regions and regions where patient inflows broadly converge should enter into inter-regional agreements that are likely to provide the former with a tool for planning the number, typology and financial coverage of outgoing admissions. These types of agreement have been implemented in recent years by boundary regions in northern Italy and have succeeded in decreasing inappropriateness and in controlling CBM flows.

The last consideration regards cross-border European mobility, recently reformed by EU directive 24/2011. Despite the significant differences between national and international mobility across Member States, the current lack of multilateral agreements modulating patient outflows among European States recalls the absence of cross-regional reciprocity agreements between southern and northern Italian regions and suggests possible scenarios at the EU scale, with an abundance of patients and money moving from the poorer to the wealthier regions of the EU.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the editors and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Ethical issues

Ethics approval is not required for this paper, since we did not collect data with personal information. Data are provided from the Italian Ministry of Health (MoH), on our request. The paper is the result of a research carried on independently by the two authors. No payment has been received from a third party (government, commercial, private foundation, etc.) for any aspect of the submitted work. No plagiarism and no conflict of interest can be addressed to this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the production of this manuscript.

Authors’ affiliations

1Department of Economics and Finance, Università Cattolica del S. Cuore, Milano, Italy. 2Department of Economics, Law and Institutions, Università Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy.

Endnotes

1. In some cases even the gap - if positive - between the DRG tariff applied for resident patients’ admissions and the national tariff (TUC, see below in the text) used to refund hospital treatments for patients in mobility, can represent an incentive to attract patients’ inflows. See for example (6).

2. Not all the fixed costs are presently covered by the DRG tariff. For example, the Central Government occasionally approves extra funds for the building.

3. Molise is a very small region located in the south of Italy which has been provided with two centers of excellence and therefore receives inpatients flows from bordering regions without the need of implementing specific rules in the contractual agreements with private providers.

4. See the Additional file 1 for the other regions.

Additional files

Contains the Appendix 1.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Inter-regional mobility for hospital care is a relevant issue for both equity reasons (high costs of care access for distant patients) and financial reasons (resource reallocation among regions).

In Italy, this phenomenon involves relevant flows of patients and money moving from the southern regions to selected northern and central regions.

The accreditation of private hospitals and the rules governing the financial coverage of hospital admissions in each region are key factors for explaining patients’ mobility.

Mutual agreements between regions which respectively manage patients’ in and out flows may help in controlling the Cross-Border Mobility (CBM) phenomenon

The Italian experience raises concerns on patients’ mobility across Europe after the implementation of the Directive 2011/24/EU.

Implications for public

In the Italian decentralised National Health Service (NHS), every year consistent flows of patients migrate from one region to another causing a considerable financial impact on regional budgets. This phenomenon follows a north-south gradient with most of the central and northern well-endowed healthcare systems attracting patients from southern Italy, where the services do not cover such a broad range of hospital specializations and/or do not guarantee the same perceived quality of care. We want to test whether, beside the well-known determinants of patients’ Cross-Border Mobility (CBM), there is an induction effect, which applies to the accredited private providers (more trained in recruiting patients via marketing activity) and is encouraged by the regional rules on the financial coverage of hospital admissions. The analysis – performed at institutional, normative and statistical level – gives evidence of an induction effect.

Citation: Brenna E, Spandonaro F. Regional incentives and patient cross-border mobility: evidence from the Italian experience. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015; 4: 363–372. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.65

References

- 1. Le Grand J, Mays N, Mulligan J. Learning from the NHS Internal Market: A Review of the Evidence. London: Kings Fund; 1998.

- 2.Cellini R, Pignataro G, Rizzo I. Competition and efficiency in health care: an analysis of the Italian case. International Tax and Public Finance. 2000;7:503–19. doi: 10.1023/A:100873750656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Propper C, Burgess S, Green K. Does competition between hospitals improve the quality of care? Hospital death rates and the NHS internal market. J Public Econ. 2004;88:1247–72. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00216-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredriksson M, Blomqvist P, Winblad U. The trade-off between choice and equity: Swedish policymakers’ arguments when introducing patient choice. J Eur Soc Policy. 2012;23:192–209. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neri S. The Structuring of Regional Health Services and the Governance of the Health System. The Italian Journal of Social Policy. 2008;3:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fattore G. Traveling for care: Inter-regional mobility for aortic valve substitution in Italy. Health Policy. 2010;117:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruzzi S. Health care regionalisation and patient mobility: the challenges for a sustainable Italian Health Service. Jean Monnet Interregional Centre of Excellence, University of Pavia; 2012.

- 8. Del Bufalo P. Mobility, maxi deficit in the South. Il Sole 24 Ore Sanità; 13-19.11.2012. Available from: http://www.sanita.ilsole24ore.com/.

- 9. Del Bufalo P. North of Italy, cradle of high specialty. Il Sole 24 Ore Sanità; 16-22.4.2013. Available from: http://www.sanita.ilsole24ore.com/.

- 10. Balia S, Brau R, Marrocu E. Free patient mobility is not a free lunch. Lessons from a decentralized NHS. Working paper No 09; 2014. Available from: http://crenos.unica.it/crenos/node/6466.

- 11.Levaggi R, Zanola R. Patients’ migration across regions: the case of Italy. Appl Econ. 2004;36:1751–7. doi: 10.1080/0003684042000227903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantarero D. Health care and patients’ migration across Spanish regions. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7:114–6. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabbri D, Robone S. The geography of hospital admission in a National Health Service with patient choice. Health Econ. 2010;19:1029–47. doi: 10.1002/hec.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glinos IA, Baeten R, Helbe M, Maarse H. A typology of cross border mobility. Health Place. 2010;16:1145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sciattella P, Spandonaro F. Mobilità dei ricoveri, elementi di complessità e incentivi delle politiche sanitarie. Monitor. 2012;29:84–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exworthy M, Peckham S. Access, choice and travel: implication for health policy. Soc Policy Adm. 2006;40:267–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2006.00489.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glinos I, Doering N, Maarse H. Travelling home for treatment and EU patients’ right to care abroad: results of a survey among German students at Mastricht University. Health Policy. 2012;105:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunt N, Mannion R, Exworthy M. A framework for exploring the policy implication of UK Medical Tourism and international patient flows. Soc Policy Adm. 2013;47:1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00833.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunt N, Mannion R. Patient mobility in the global marketplace: a multidisciplinary perspective. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;14:2. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bustamante AV. Globalization and medical tourism: the North American experience. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:47–9. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiebout C. A pure theory of local expenditures. J Polit Econ. 1956;64:416–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Italian Ministry of Health [homaoage on the internet]. Available from: http://www.salute.it.

- 23.France G, Taroni F, Donatini A. The Italian health-care system. Health Econ. 2005;14:S187–202. doi: 10.1002/hec.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenna Brenna, E E. Quasi-market and cost-containment in Beveridge systems: the Lombardy model of Italy. Health Policy. 2011;103:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maino F, Neri S. Explaining welfare reforms in italy between economy and politics: external constraints and endogenous dynamics. Soc Policy Adm. 2011;45:445–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00784.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bordignon M, Boeri T. Il federalismo? Meglio se a velocità variabile [internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.lavoce.info.

- 27. Brenna E. The Local Health Authorities’ role in managing hospital expenses: empirical findings from the Local Health Authority of Como. Sanità Pubblica e Privata 2007; 6: 39-49. Available from: http://preview.periodicimaggioli.it/browse.do?id=23.

- 28. Caroppo MS, Turati G. The Italian regional health care systems. Vita e Pensiero ed; 2007.

- 29. Cantù E, Ferrè F, Sicilia M. Regions and private accredited health firms, the possible managing strategies. Rapporto OASI Cergas Bocconi; 2011.

- 30.Le Grand J. Competition, cooperation, or control? Tales from the British National Health Service. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18:27–39. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centre for Market and Public Organisation (CMPO). Hospital care in England: who will choose? Research in Public Policy. University of Bristol; 2007. Available from: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmpo/audio/propper.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Contains the Appendix 1.