Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to provide insight into the preferences for and perceptions of medical error disclosure (MED) by members of the public in Oman.

Methods:

Between January and June 2012, an online survey was used to collect responses from 205 members of the public across five governorates of Oman.

Results:

A disclosure gap was revealed between the respondents’ preferences for MED and perceived current MED practices in Oman. This disclosure gap extended to both the type of error and the person most likely to disclose the error. Errors resulting in patient harm were found to have a strong influence on individuals’ perceived quality of care. In addition, full disclosure was found to be highly valued by respondents and able to mitigate for a perceived lack of care in cases where medical errors led to damages.

Conclusion:

The perceived disclosure gap between respondents’ MED preferences and perceptions of current MED practices in Oman needs to be addressed in order to increase public confidence in the national health care system.

Keywords: Medical Error; Disclosure; Ethics, Medical; Oman

A medical error is defined as an act or omission that would have been judged as erroneous by knowledgeable peers at the time of occurrence.1 This definition includes both acts and omissions that result in harm to the patient (adverse events) and those that do not cause any harm (near misses).

It is generally accepted that the best course of action to take following an identified medical error is full and appropriate disclosure. While there seems to be an international consensus in favour of full disclosure when there has been an adverse event, in situations which were not harmful, so-called ‘near misses’, there is no consensus on disclosure.2 Some medical ethicists insist on full disclosure, citing reasons such as respect for autonomy and the imperative principle of truth-telling.3 However, others prefer to allow physicians and hospitals some discretion on this issue. The Oman Ministry of Health’s (MOH) code of professional conduct for doctors in Oman is an accurate reflection of this debate. It states that doctors should “act immediately to put matters right, if a patient under [their] care has suffered serious harm, through misadventure or any other reason”.4 It goes on to state that doctors should give a full explanation to the patient and explain the possible short- and long-term effects of the error. Doctors are also urged to offer an apology to the patient, when appropriate.4 However, on the topic of near misses, the MOH code, like many other national codes, is conspicuously silent.

Studies show that patients prefer that medical errors be disclosed and generally feel that disclosure practices could be improved.5–7 Hobgood et al. found that this disclosure preference is associated with measures of patient satisfaction: “Teaching physicians about error disclosure techniques may help to avoid medical errors and increase patient satisfaction”.8 A study by Witman et al. found that virtually all patients (98%) desired some acknowledgment of even minor errors.9 While full disclosure is the recommendation, the corollary to this is that non-disclosure is in violation of ethical principles and is also likely to increase chances of litigation.10

It is also clear from the literature that patients want full disclosure of both harmful and potentially harmful events.5–10 Furthermore, such disclosure has been shown to positively influence the response of patients and their relatives to medical errors.5–10 Unfortunately, full disclosure is not always a regular component of physician behaviour, with one study reporting that 76% of doctors admitted to not disclosing a serious error to a patient.11 Concern about the occurrence of a medical error seems to be a global phenomenon, with several studies in different countries identifying high rates of patient anxiety (39% and 48% in the USA and Iran, respectively).12,13 A study by Ghalandarpoorattar et al. identified a perceived gap in medical error disclosure, where members of the public believed that medical errors were not fully disclosed.14

Nevertheless, not all patients want the same level of disclosure and the nature of disclosure is likely to depend on culture. Cultural differences relating to error disclosure are beginning to emerge from the literature.15 In Oman, the topic of medical errors is openly discussed at the governmental level as well as within the MOH.16 A community survey carried out in Oman assessed understanding of the term ‘medical error’. The survey revealed that 49% believed they knew what a medical error was and 49% felt that the primary cause of a medical error was due to uncaring healthcare professionals.16 Omanis are known to travel overseas for costly medical care despite an improving and government-funded national healthcare system. It therefore seems that there is a gap between public perception and the reality of error disclosure and quality of care from health providers in Oman. As such, this study aimed to provide insight into the preferences for and perceptions of medical error disclosure by members of the public in Oman.

Methods

Between January and June 2012, an online survey was used to collect responses from members of the public across five governorates of Oman. A convenience snowball sampling technique was used to source respondents which involved students at the Sohar campus of Oman Medical College passing on the web address of the survey to their friends and relatives.

There were three main sections to the survey, which was administered in English. The first two sections were based on similar survey items used in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia.17 Questions in these sections covered the types of medical errors to be disclosed and responsibility for disclosing such errors. Respondents were asked to provide three different responses for each question (their personal preference, what they believed was generally appropriate and what they believed was the current practice in Oman). The dependent variable for each of these survey items was an ordinal set of response options.

The final section of the survey involved a case scenario of a medical error. Respondents were asked to rate the quality of care provided by the doctor in the case scenario. The dependent variable was the rating of quality of care on a 10-point scale. This section involved two between-group independent variables. The stem description of the case scenario and the nature of the error was identical in all four cases. The stem read:

Mr Ahmed is admitted to the hospital to receive an intravenous treatment. He receives the treatment in his room. Unfortunately, Mr Ahmed does not tolerate the treatment well; he starts sweating and feels nauseous. When the doctor realizes that Mr Ahmed has received an overdose of the drug by mistake, the intravenous line is stopped immediately and he is transferred to the intensive care unit to be watched closely and to receive treatment to remove the drug.

This stem description of the case scenario was then followed by one condition of each of the two independent variables: whether there was full disclosure following the error and whether an adverse event resulted from the error. There were therefore four different versions of the case scenario, covering harm to patient/no harm to patient and full disclosure/no disclosure [Table 1]. Each respondent received one of the four versions. A repeated measures Friedman analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to assess the distribution of the variables.

Table 1:

Case scenario endings for the two independent variables with four different combinations

| Independent variable | |

|---|---|

| Disclosure | Harm |

| Full disclosure | Harm |

| The doctor takes the time to explain the situation to Mr Ahmed. He admits that an error was made and apologises to the patient. He also tells him that the hospital will take all necessary measures to ensure that such an incident does not occur again. | Mr Ahmed’s kidneys were seriously damaged in spite of the treatment given in the ICU. Therefore he cannot receive the original treatment. He will have to be treated with a less effective drug. |

| No disclosure | No harm |

| The doctor does not mention the error to Mr Ahmed, who assumes that it was just an unforeseeable complication. | Mr Ahmed stays in the ICU for two days and then he leaves the hospital without further health problems. |

ICU = intensive care unit.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Research Review Board at the Oman Medical College. Consent was obtained from all of the participants in the study.

Results

A total of 205 adult members of the public completed the survey, of which 77% were Omani. The male to female ratio was 11:8. More than 60% of the participants had studied at a higher education level and less than 8% of the respondents had not completed secondary school.

There were no significant differences between the personal preferences of the respondents and what they felt was generally appropriate with regards to medical error disclosure. Only 5% of the respondents reported that they would not like to be informed of a medical error. A total of 60% of the respondents reported a desire to be informed of an error even if it caused no or minor harm (29% and 31%, respectively).

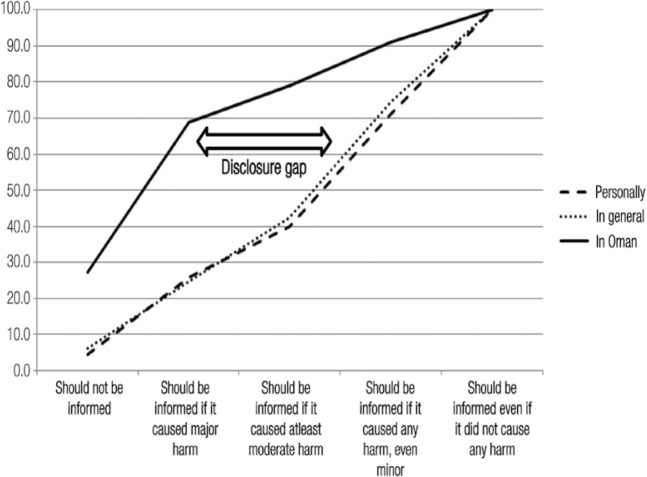

The repeated measures Friedman ANOVA by rank indicated statistically significant differences in the distributions regarding what type of medical errors should be disclosed (F [2,158] = 265.4; P <0.001). In the question about perceived medical error disclosure practices in Oman, 42% of respondents felt that they would only be informed if the error caused serious harm and a further 27% felt that they would not be informed of any error. This difference between preferences and perceived practices is demonstrated by the leftward shift towards less disclosure in the cumulative distribution curve shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Cumulative distribution curve showing the personal (dashed line) and general (dotted line) preferences regarding the types of medical errors to be disclosed and perceptions of current error disclosure practices in Oman (solid line) among members of the Omani public (N = 205).

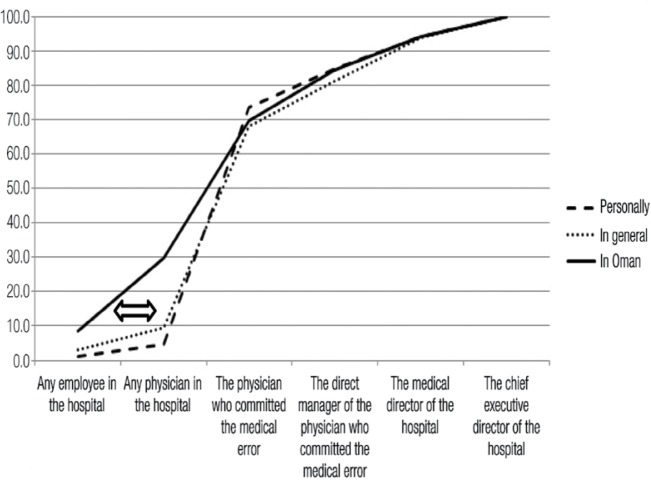

Using the repeated measures Friedman ANOVA by rank, significant differences were also found in the distributions regarding who should disclose a medical error (F [2,158] = 53.2; P <0.001]. There were no significant differences between the personal preferences of respondents and what they thought was generally acceptable. The majority of the respondents (69%) believed that the doctor who was responsible for the error should be the one to disclose it (95% confidence interval: 62.1–77.7). However, there was a significantly different distribution with perceived current practices of medical error disclosure in Oman, with fewer respondents thinking that the responsible doctor would be the one to disclose the error and more respondents believing that another physician would take responsibility for the disclosure. Similarly to error type, this difference was also observable as a leftwards shift in the cumulative distribution curve [Figure 2].

Figure 2:

Cumulative distribution curve showing the personal (dashed line) and general (dotted line) preferences regarding the responsibility of disclosing a medical error and perceptions of current error disclosure practices in Oman (solid line) among members of the Omani public (N = 205).

Although the core content relating to the medical error in the stem description of the case scenario was identical, very different responses were noted depending on the two between-group variables (the nature of the disclosure and the outcome of the error) [Table 2]. In the case scenario where the physician provided full disclosure following a near miss, the quality of the care was rated as extremely good [median: 9; mode: 9]. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant between-group differences for both factors of harm and disclosure. The score given for quality of care was significantly lower for the case scenarios which resulted in an adverse event (F [1,160] = 35.7; P <0.001). The score given for quality of care was significantly higher for the case scenario which resulted in full disclosure (F [1,160] = 95.6; P <0.001).

Table 2:

Median scores* rating the quality of physician care in four combinations of a medical error case scenario (N = 205)

| Independent variable | Quality of care Median score (mode) | |

|---|---|---|

| Harm | No harm | |

| Full disclosure | 5 (3) | 9 (9) |

| No disclosure | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

Scores ranged from 1 (extremely poor care) to 10 (extremely good care).

Discussion

The results of this survey suggest that members of the Omani public preferred that medical errors be disclosed, whether they resulted in harm or not. As in similar studies, there was a broad agreement between the personal preferences of the respondents and what they thought would generally be considered acceptable by other members of society.17 This high level of agreement likely arises from the belief conformity common in traditionally collectivist societies, such as Oman, in which an individual’s beliefs are encouraged to match those of wider society.

However, both personal and general preferences regarding medical errors were clearly divergent from what the respondents considered to be normal practice in Oman; comparatively few individuals believed that doctors in Oman would disclose medical errors that caused moderate, minor or no harm. In addition, some respondents believed that even major errors would not be disclosed to patients. Thus, there was a disclosure gap between preferences for full disclosure and what the respondents believed would typically be disclosed in an Omani hospital. Similar perceived disclosure gaps have been reported in other countries, including the USA, Iran, Canada, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.16,18–20

Respondents showed a strong preference that the disclosure of a medical error should be undertaken by the physician who committed the error. This preference has been well-documented in the literature.3,5,6,8–10,16–18,20,21 Again, there was a perceived gap between the preferences indicated and what members of the public considered to be normal practice in Oman, with more respondents indicating that the person to disclose the medical error would be someone other than the physician responsible. A study performed in Saudi Arabia found that 60% of respondents preferred the doctor responsible for the error to be the person to disclose it, which is slightly lower than the findings of the current study.17

In the current study, the amount of harm caused by the medical error and the extent of disclosure both strongly influenced the respondents’ ratings of the quality of patient care. The fact that an adverse event had an influence on this rating is not surprising as this has been repeatedly demonstrated in the literature.5,8,9,21 It is presumably the harm factor that is alluded to in the MOH code of professional conduct when it asserts that there should be full disclosure with an apology, “if appropriate”.4 Although this information is useful, it is not of particular clinical use, as there are limited possibilities to affect change on the patient’s condition retrospectively. A more useful finding is the significant influence of full disclosure on the respondents’ ratings of physician-provided patient care; in fact, disclosure, rather than harm, appeared to have a greater influence on these ratings. In the current study, when case scenarios involving adverse events were compared, there was a dramatic increase in the patient care ratings for scenarios which resulted in full disclosure, with an increase in the median value from two to five. In the scenarios with full disclosure, the doctor was rated more highly, even if other situational and health factors were identical.

This study found that the Omani public’s willingness to accept medical errors made by health professionals was particularly high, with quality of care ratings being very high when a near-miss error was fully disclosed. The literature suggests that patients are less likely to make a formal complaint or initiate legal proceedings following a medical error if there has been full disclosure.10,11

In at least one other Islamic country, the disclosure gap regarding medical errors has been attributed to a paternalistic culture in medical practice, in which the physician decides whether telling the patient about the error would be of benefit.16 A similar paternalistic culture has been noted in Oman.22 However, as is clear from the findings of the current study, there is a strong preference by members of the public for full disclosure following an error, even in the case of a near miss.

Automated geolocation tagging of respondents taking part in the online survey showed that the survey was completed across a wide geographical area, including five governorates in Oman. This is likely to ameliorate the potential limitations of representation of the general population arising from data collected using a convenience snowball sampling method. It must also be emphasised that this study did not collect any data on rates of error disclosure in Oman. The disclosure gaps that were identified, therefore, were gaps between the preferences of the members of the public and what they believed to be common practice in Oman. Thus it is not possible to comment on the veracity of these beliefs, only that they are widely held by members of the public.

Increasing patient satisfaction in relation to medical error disclosure in Oman is an important but ancillary goal to the primary objective of improving patient safety. These findings regarding the Omani public’s preferences for error disclosure should be set within the patient safety context, where the overarching goal is to reduce the occurrence of medical errors in Oman. The relationship between patient satisfaction and patient safety in Oman should be explored in future research.

Conclusion

There is a gap between personal and general preferences for medical error disclosure and the perception of current error disclosure practices in Oman among members of the Omani public. There is a need to address this apparent lack of confidence in error disclosure. Furthermore, there is a need to ensure that doctors in Oman take a more active and demonstrable role in proximate error disclosure with their patients. The results of this study suggest that the Omani population is very generous in their willingness to accept errors as long as there is full and complete disclosure, as shown by the high ratings of care given to doctors who fully disclosed their medical errors. This mitigating effect may enable Omani patients who have been the recipient of a medical error to be more understanding and accepting of even harmful events if medical professionals in Oman develop an appropriate culture of open disclosure.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Dr Saleh Al-Khusaiby, Dean of the Oman Medical College, for his invaluable guidance regarding contextual aspects of medical ethics as well as medical error reporting in Oman.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a safer health system. From: www.iom.edu/∼/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf Accessed: Sep 2014. [PubMed]

- 2.Elder NC, Pallerla H, Regan S. What do family physicians consider an error? A comparison of definitions and physician perception. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birks Y. Duty of candour and the disclosure of adverse events to patients and families. Clinical Risk. 2014;20:1–2. 19–23. doi: 10.1177/1356262213516937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oman Ministry of Health . Code of Professional Conduct for Doctors. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289:1001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manser T, Staender S. Aftermath of an adverse event: Supporting health care professionals to meet patient expectations through open disclosure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:728–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor E, Coates HM, Yardley IE, Wu AW. Disclosure of patient safety incidents: A comprehensive review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:371–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobgood C, Peck CR, Gilbert B, Chappell K, Zou B. Medical errors–what and when: What do patients want to know? Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1156–61. doi: 10.1197/aemj.9.11.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2565–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440210083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, Martinson BC, Gunter MJ, Reed GW, Gurwitz JH. Health plan members’ views on forgiving medical errors. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu AW, Cavanaugh TA, McPhee SJ, Lo B, Micco GP. To tell the truth: Ethical and practical issues in disclosing medical mistakes to patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:770–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Gallagher TH, Waterman B, Jeffe DB, Dunagan WC, et al. Patients’ concerns about medical errors during hospitalization. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kianmehr N, Mofidi M, Saidi H, HajiBeigi M, Rezai M. What are patients’ concerns about medical errors in an emergency department? Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12:86–92. doi: 10.12816/0003092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghalandarpoorattar SM, Kaviani A, Asghari F. Medical error disclosure: The gap between attitude and practice. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:130–3. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlinger N, Wu AW. Subtracting insult from injury: Addressing cultural expectations in the disclosure of medical error. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:106–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mandhari AS, Al-Shafaee MA, Al-Azri MH, Al-Zakwani IS, Khan M, Al-Waily AM, et al. A survey of community members’ perceptions of medical errors in Oman. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammami MM, Attalah S, Al Qadire M. Which medical error to disclose to patients and by whom? Public preference and perceptions of norm and current practice. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beer Z, Guttman N, Brezis M. Discordant public and professional perceptions on transparency in healthcare. QJM. 2005;98:462–3. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levinson W, Gallagher TH. Disclosing medical errors to patients: A status report in 2007. CMAJ Journal. 2007;177:265–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorgham SR, Mohamed LK. Personal preference and perceived barriers toward disclosure and report of incident errors among healthcare personnel. Life Sci J. 2012;9:4869–80. doi: 10.1.1.381.3895. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwappach DL, Koeck CM. What makes an error unacceptable? A factorial survey on the disclosure of medical errors. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:317–26. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Adawi S, Dorvlo AS, Burke DT, Al-Bahlani S, Martin RG, Al-Ismaily S. Presence and severity of anorexia and bulimia among male and female Omani and non-Omani adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1124–30. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]