Abstract

The conversion of vitamin D into an active ligand for the vitamin D receptor requires 25-hydroxylation in the liver and 1α-hydroxylation in the kidney. Mitochondrial and microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase enzymes catalyze the first reaction. The mitochondrial activity is associated with sterol 27-hydroxylase, a cytochrome P450 (CYP27A1); however, the identity of the microsomal enzyme has remained elusive. A cDNA library prepared from hepatic mRNA of sterol 27-hydroxylase-deficient mice was screened with a ligand activation assay to identify an evolutionarily conserved microsomal cytochrome P450 (CYP2R1) with vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activity. Expression of CYP2R1 in cells led to the transcriptional activation of the vitamin D receptor when either vitamin D2 or D3 was added to the medium. Thin layer chromatography and radioimmunoassays indicated that the secosteroid product of CYP2R1 was 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Co-expression of CYP2R1 with vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) elicited additive activation of vitamin D3, whereas co-expression with vitamin D 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) caused inactivation. CYP2R1 mRNA is abundant in the liver and testis, and present at lower levels in other tissues. The data suggest that CYP2R1 is a strong candidate for the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.

Vitamin D regulates calcium and phosphate metabolism by activating the vitamin D receptor, a transcription factor and member of the nuclear receptor family. In the 1920s, McCollum, Mellanby, and Pappenheimer (see Ref. 1) showed that deficiency of vitamin D caused rickets in experimental animals. Subsequently, the structure of vitamin D and its origins from plant and animal steroids were determined, and the roles of the vitamin in the mobilization of minerals from the diet and in bone were defined. The liver was shown to be required for the activation of vitamin D by 25-hydroxylation (2, 3). Although 25-hydroxyvitamin D was more active than vitamin D in many bioassays (4), the most potent hormone was 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (5, 6), which was synthesized from 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the kidney (7). The molecular mechanism of vitamin D action was manifest with the identification (8) and cDNA cloning (9) of the vitamin D receptor.

Hydroxylation reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450s (CYP)1 activate and inactivate vitamin D as a ligand for the receptor. 25-Hydroxylation is performed in the liver by two different enzymes, one located in the mitochondria (10), identified as the CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase (11–15), and a second in microsomes (16, 17), which has not been identified in most species. A second mitochondrial P450 (CYP27B1), for which an encoding cDNA was isolated by expression cloning (18), catalyzes 1α-hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the kidney, and a third mitochondrial P450, vitamin D 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1), inactivates the vitamin in this tissue (19–21). Together, these enzymes regulate the systemic and local levels of vitamin D through complex feedback mechanisms mediated in part by the vitamin D receptor (22).

The existence and physiological importance of the two hepatic vitamin D 25-hydroxylase enzymes are demonstrated in humans (23, 24) and mice (25, 26) by mutations in the mitochondrial CYP27A1 vitamin D 25-hydroxylase gene. Loss of this enzyme has profound effects on cholesterol metabolism, as CYP27A1 catalyzes an essential reaction in bile acid synthesis. In contrast, vitamin D metabolism is normal in individuals and mice with no functional CYP27A1. These findings indicate that the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase can compensate for loss of the mitochondrial activity.

In the current study, a cDNA library made from hepatic mRNA of mice deficient in the gene encoding the mitochondrial CYP27A1 enzyme was screened using a vitamin D receptor-based, ligand activation assay (18). A single cDNA specifying a microsomal P450 enzyme termed CYP2R1 with previously unknown substrate specificity was identified. The biochemical properties and tissue distribution of CYP2R1 are consistent with this enzyme being the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Plasmids

A mouse adrenodoxin cDNA (mAdx, nucleotides 41–772 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. L29123) was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from random hexamer-primed mouse hepatic cDNAs using the following oligonucleotide primers: Forward (5′-GCCTATGTCGACTCAGCACTGCGCAGGACTCC-3′) and Reverse (5′-GCGGGATCCGACAGCACAGCTACTCACAC-3′). The amplified DNA was digested with the enzymes SalI and BamHI and ligated into pCMV6 (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. AF239250). The adrenodoxin expression vector encoded the expected electron transport enzyme activity in transfected cells, as judged by the ability of the protein to stimulate the vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activity of sterol 27-hydroxylase.

A mouse vitamin D 24-hydroxylase cDNA (mCYP24A1, nucleotides 281–2200 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. D89669) was amplified by PCR from random hexamer-primed kidney cDNA. The RNA for this cDNA synthesis reaction was isolated from a mouse injected intraperitoneally with 36 pmol of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D/g of body weight for 5 h prior to tissue harvest. Oligonucleotide primers for the amplification reaction were: Forward (5′-GCCTATGTCGACACTTCAGAACCCAACAGCAC-3′) and Reverse (5′-ATTATGCGGCCGCAGTGACATCAGGCTCTTGAG-3′). The amplified DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes SalI and NotI and ligated into the pCMV6 vector.

Human cytochrome P450 subfamily 3A, polypeptide 4 (hCYP3A4, nucleotides 98–1617 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. NM_017460), and cytochrome P450 2R1 (hCYP2R1) cDNAs were amplified by PCR from liver QUICK-clone cDNA (Clontech). Oligonucleotide primers for the hCYP3A4 cDNA were: Forward (5′-GCCTATGTCGACAGTGATGGCTCTCATCCCAG-3′) and Reverse (5′-ATTATGCGGCCGCTTCAGGCTCCACTTACGGTG-3′). The amplified DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes SalI and NotI and then ligated into the pCMV6-SPORT vector (Invitrogen). The CYP3A4 expression vector encoded testosterone 6β-hydroxylase enzyme activity in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells, as judged by thin layer chromatography. Oligonucleotide primers for the hCYP2R1 cDNA were: Forward (5′-GCCTATGTCGACTGTGGAGTTCGCACCTCCAG-3′) and Reverse (5′-ATTATGCGGCCGCAACCAAGTTCAGGGATAAGG-3′). The amplified DNA was digested with the enzymes SalI and NotI and then ligated into the pCMV6 vector.

A DNA fragment encompassing the 5′-flanking region of the mouse osteopontin gene (nucleotides 1–862 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. D14816) was amplified via PCR from mixed strain C57Bl/6J;129S6/SvEv mouse genomic DNA. Oligonucleotide primers were: Forward (5′-ATTATGCGGCCGCTTCAGGCTCCACTTACGGTG-3′) and Reverse (5′-CCGCTCGAGCTTGGCTGGTTTCCTCCGAGAATG-3′). The amplified DNA product was digested with the restriction enzymes HindIII and XhoI and then ligated into the pTK-LUC reporter plasmid (27).

A mouse 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-hydroxylase cDNA (mCYP27B1, GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. AB006034) was a kind gift of Professor Shigeaki Kato (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). The mouse sterol 27-hydroxylase cDNA (mCYP27A1) used in these studies was generated previously (28).

Expression Cloning

A cDNA library was made from 3 μg of poly(A)+ hepatic RNA isolated from mice deficient in sterol 27-hydroxylase (25) using the SUPERSCRIPT plasmid system for cDNA synthesis (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was initiated by NotI oligo(dT) primer-adapters; the cDNA products were ligated to SalI adapters, digested with the restriction enzyme NotI, size-fractionated by gel filtration chromatography, and then ligated into NotI- and SalI-digested pCMV-SPORT 6 vector. Nucleic acids in the ligation mixture were precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 5 μl of deionized, distilled H2O. Escherichia coli Electromax DH10B cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with 1 μl of the resuspended DNAs. The transformation mixture was diluted into 500 ml of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml). An aliquot (1.25 ml) of the diluted culture (containing ~100 transformants) was added to each well of a 96-well block (Qiagen) and incubated with shaking for 20–24 h at 37 °C. Plasmid DNA was isolated from the bacterial cultures using the QIAprep96 Turbo Miniprep kit (Qiagen).

HEK 293 cells (American Type Culture Collection CRL no. 1573) were transfected with pools of ~100 cDNAs using the FuGENE™ 6 reagent (Roche Applied Science). The cells were maintained in monolayer culture at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 8.8% CO2, 91.2% air in low glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. On day 0 of an expression cloning experiment, 25,000 cells/well were plated in 96-well plates (Corning Costar, no. 3595) in a volume of 100 μl of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) dextran-charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum. On day 1, cells were transfected with a mixture containing 0.45-μl FuGENE™ 6 and 150 ng of plasmid DNA comprising 20 ng of pCMX-β-galactosidase (29), 20 ng of pTK-MH100X4-LUC (27), 20 ng of pCMX/GAL4-VDR (see below), 10 ng of pVA1 (30), 5 ng of pCMV6/mAdx, and 75 ng of cDNA pool. Cells were returned to the incubator for 8–10 h, and then vehicle (ethanol) or 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (Sigma) substrate was added to a final concentration of 10 nM. After an additional 16–20 h of incubation, cells were lysed by the addition of 100 μl/well Lysis Buffer (2% (v/v) CHAPS, 0.6% (w/v) phosphatidylcholine, 2.5 mM Tris phosphate, pH 7.8, 0.6% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 15% (v/v) glycerol, 4 mM EGTA, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DL-dithiothreitol, and 1% (w/v) Pefabloc SC (Centerchem)). The 96-well plates were shaken for 5 min at 23 °C, and then 20 μl of cell lysate from each well were transferred to a fresh 96-well assay plate (Corning Costar no. 3922). Thereafter, 100 μl of Luciferase Assay Buffer (4 mM ATP (Roche Applied Science), 20 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 M KPO4) was added to each well, and luciferase activity was measured in a Dynex MLX microtiter plate luminometer running the Revelation MLX version 4.25 software after the addition of 100 μl of Luciferin Solution (1 mM D-luciferin (Molecular Probes) in 0.1 M KPO4). β-Galactosidase enzyme activity was determined in cell lysates using a Dynex Opsys MR machine running the Revelation Quicklink software; an aliquot (40 μl) of cell lysate was transferred to each well of a fresh 96-well plate (Corning Costar no. 3598), followed by the addition of 125-μl of β-Galactosidase Assay Buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 8 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 0.4% (w/v) 2-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (Roche Applied Science), and 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and an incubation of 10 min at 37 °C prior to measuring the absorbance at A405. Relative luciferase units were calculated by dividing the measured luciferase activities by the absorbance values per min determined in the β-galactosidase assay. All values are expressed as means ± S.E. of measurement derived from triplicate wells.

Vitamin D Receptor Activation Assay and Ligands

The GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase receptor-reporter system was composed of the pTK-MH100X4-LUC plasmid (27), and pCMX/GAL4-VDR, which specifies a fusion protein consisting of amino acids 1–147 of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae galactose 4 (GAL4) transcription factor (encoded by nucleotides 2901–3353 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. X85976) and amino acids 90–427 of the human vitamin D receptor (hVDR, encoded by nucleotides 383–1397 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. 44507882). The VDR/vitamin D response element (VDRE)-luciferase system used here consisted of the SPPX3-TK-LUC plasmid (31) and a plasmid expressing the full-length mouse vitamin D receptor (pCMX/mVDR, nucleotides 109–1377 of GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. D31969) (32). The VDR/osteopontin-luciferase system was composed of the osteopontin-LUC plasmid (0.862-kb DNA fragment encompassing the mouse osteopontin gene promoter ligated into the pTK-LUC vector (Ref. 27)), and the pCMX/mVDR DNA described above. Transfection experiments with the GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase receptor-reporter systems were carried out as described under “Expression Cloning.” For the VDR/VDRE-luciferase and VDR/osteopontin-luciferase systems, the plasmid DNA mixtures (150 ng of DNA total) contained 5 ng of pCMX/mVDR, 20 ng of pSPPX3-TK-LUC or pOsteopontin-LUC, 20 ng of pCMX-β-galactosidase, 10 ng of pVA1, and 95 ng of CYP expression vector or pCMV6 plasmid DNA.

Secosteroids used in the experiments reported here (vitamin D2, vitamin D3, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) were obtained from Sigma and added to the culture medium in ethanol (1 μl/ml of medium). Stock solutions of these compounds ranged in concentration from 10−2 to 5 × 10−7 M and were stored at −20 °C.

Thin Layer Chromatography

HEK 293 cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105 cells/60-mm dish in 2.5 ml of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) dextran-charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. On day 2, cells were transfected with FuGENE™ 6 reagent and a mixture of plasmid DNAs (3.5 μg total) containing 0.5 μg of pVA1, and either 3 μg of pCMV6, 3 μg of pCMV6-h2R1, 1.5 μg of pCMV6, and 1.5 μg of pCMV6-mAdx, or 1.5 μg of pCMV6-mCYP27A1 and 1.5 μg of pCMV6-mAdx. After 18 h, the transfection medium was removed from the dish and replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium supplemented as above and containing 4.6 × 10−7 M [4-14 C]vitamin D3 (Amersham Biosciences). For cells transfected with the pCMV6-mCYP27A1 plasmid, the medium was brought to a final concentration of 10−6 M vitamin D3 by the addition of unlabeled secosteroid. Cells and medium were harvested 96 h later, and vitamin D metabolites were extracted with 8 ml of chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v), and then dried under a stream of N2. The extracted metabolites were resuspended in 50 μl of acetone and resolved by thin layer chromatography on pre-scored LD5DF silica gel 150-Å plates (Whatman). Solvent systems of cyclohexane:ethyl acetate (3:2, v/v), chloroform:ethyl acetate (3:1, v/v), and 2,2,4-trimethylpentane:ethyl acetate:acetic acid (50:50:17, v/v/v) were used. Radiolabeled vitamin D metabolites were detected by phosphorimage analysis on a BAS1000 machine (Fuji Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). Aliquots (5 μl) of 10−2 M stock solutions of unlabeled standards (vitamin D3, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3, and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) dissolved in ethanol were chromatographed in adjacent lanes on the plates and visualized by iodine staining (33).

Radioimmunoassays

The γB 25 hydroxyvitamin D radioimmunoassay kit (Alpco Diagnostics) was used for the quantitative determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in medium from HEK 293 cells cultured in the 96-well plate format described above. Cells were transfected via the FuGENE™ 6 reagent with 150 ng of total plasmid DNA comprising 5 ng of pCMX/mVDR, 20 ng of SPPX3-TK-LUC, 20 ng of pCMX-β-galactosidase, 10 ng of pVA1, and either 95 ng of pCMV6, pCMV6-h2R1, or pCMV6 SPORT-m2R1, or 45 ng of pCMV6-mCYP27A1 and 45 ng of pCMV6-mAdx. After 10 h, ethanol vehicle, or vitamin D3 at final concentrations of 0.5 or 1 μM, was added to the medium. Radioimmunoassays were performed 44 h later on 50-μl aliquots of pooled medium from triplicate wells following directions provided by the manufacturer. The correlation coefficient of accuracy for the radioimmunoassay kit was r = 0.95. Sensitivity was >3 nmol/liter. Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays also were performed on cell lysates to ensure that transfected plasmids were expressed.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from mouse tissues using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). Aliquots (100 μg) of total RNA were treated with deoxyribonuclease I (DNA-free; Ambion). cDNA synthesis was initiated from 2 μg of deoxyribonuclease I-treated RNA using random hexamer primers and Taqman reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems (ABI)). For each real time PCR reaction, which was carried out in triplicate, cDNA synthesized from 20 ng of deoxyribonuclease I-treated RNA was mixed with 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI). Samples were analyzed on an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used in these experiments were: CYP2R1 mRNA, 5′-CAGAAAGACGCTGAAAGTGCAA-3′ and 5′-CAGTGTATTTGTGTTTACTTGGCTTTATAA-3′; CYP24A1 mRNA, 5′-CTCCCTATGGATGCAGTATGTATAGTG-3′ and 5′-TTTAAAAACGTTGTCAGTAGGTCATAACT-3′; CYP27A1 mRNA, 5′-GGAGGGCAAGTACCCAATAAGA-3′ and 5′-TGCGATGAAGATCCCATAGGT-3′; CYP27B1 mRNA, 5′-TCAGCAGGCATCGCAGAAC-3′ and 5′-GCATTGGATCCTGAGGAATGA-3′; cyclophilin mRNA, 5′-TGGAGAGCACCAAGACAGACA-3′ and 5′-TGCCGGAGTCGACAATGAT-3′.

RESULTS

An expression cloning assay was established in cultured cells and optimized to isolate cDNAs encoding enzymes capable of activating vitamin D3 by 25-hydroxylation. The vitamin D-responsive reporter system consisted of a plasmid encoding a chimeric protein composed of the DNA binding domain of the yeast GAL4 transcription factor fused to the ligand binding domain of the human vitamin D receptor, and a reporter plasmid in which luciferase expression was directed by a heterologous promoter consisting of four GAL4 DNA response elements linked to basal expression elements from the herpes simplex 1 TK gene; this receptor-reporter system is referred to as GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase. The introduction of these plasmids into HEK 293 cells followed by the addition of saturating levels of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to the culture medium led to a >700-fold increase over background of luciferase enzyme activity versus that observed in the absence of ligand (data not shown).

To determine the maximum number of cDNAs that could be assayed at one time in the expression screen, dilution experiments were performed with the CYP27A1 expression plasmid, the receptor-reporter system, and the precursor substrate, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3. A luciferase enzyme activity that was 3-fold over background was observed when the sterol 27-hydroxylase plasmid was diluted 190-fold with a control plasmid lacking a cDNA insert. These results indicated that a cDNA pool size of ~100–200 could be reliably screened in the expression cloning assay when 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 was used as the precursor. They also confirmed that the sterol 27-hydroxylase enzyme is capable of 25-hydroxylating both vitamin D3 and 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (11, 34, 35).

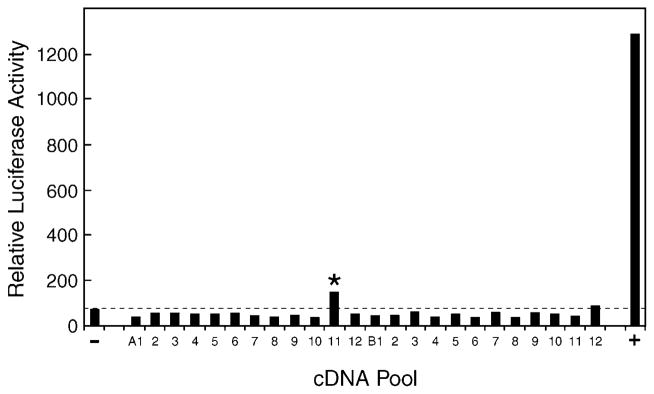

To avoid isolating cDNAs encoding the sterol 27-hydroxylase, the cDNA library used in these studies was constructed using poly(A)+ mRNA isolated from livers of mice lacking sterol 27-hydroxylase (25). The resulting library was estimated to contain 7.9 × 106 independent transformants with an average cDNA insert size of 1.5 kb. Aliquots of the library containing ~100 cDNAs were transfected together with the GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase receptor-reporter plasmids into HEK 293 cells. The data generated from one such experiment is shown in Fig. 1. One cDNA pool (A11) produced a luciferase enzyme activity that was ~2-fold over that generated in mock transfected cells. Subsequent cycles of cDNA purification and screening were performed on the A11 pool to identify a single cDNA that encoded the vitamin D-activating activity.

Fig. 1. Expression cloning of vitamin D 25-hydroxylase cDNA.

A cDNA library was constructed from hepatic mRNA purified from sterol 27-hydroxylase-deficient mice and divided into pools of ~100 cDNAs each. Plasmid DNA (75 ng) from individual pools was combined with 20 ng of a GAL4-vitamin D receptor expression plasmid, 20 ng of a GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter gene plasmid, 20 ng of a CMV-β-galactosidase plasmid (for normalization purposes), 5 ng of a mouse adrenodoxin expression plasmid (to boost the activity of mitochondrial P450s encoded by the cDNA pools), and 10 ng of the VA1 plasmid (to increase expression from the receptor and reporter gene plasmids; Ref. 30), and introduced via the FuGENE™ 6 reagent (Roche) into HEK 293 cells cultured in microtiter plates. 1α-Hydroxyvitamin D3 (10 nM) was added to the medium 8–10 h later. After an additional incubation of 16–20 h in an atmosphere of 91.2% air and 8.8% CO2, the cells were disrupted in the microtiter plate by the addition of 100 μl of Lysis Buffer, and aliquots of 20 and 40 μl were assayed by luminometry and spectroscopy, respectively, for luciferase and β-galactosidase enzyme activity. Relative luciferase activity was calculated for each well by dividing luciferase enzyme activity by the amount of β-galactosidase activity per unit of time. One pool of cDNAs (A11, marked by asterisk) produced a modest activation of the vitamin D receptor-reporter system compared with that obtained with the pCMV vector alone (−) and a positive control (+) consisting of a plasmid encoding the mouse CYP27A1 vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.

A total of ~110,000 cDNAs in 1056 pools were screened. Seven positive cDNA pools were identified, revealing four different encoded proteins. cDNAs for the retinoid X receptor α, hypoxia induction factor 1α, and the SEC14-related protein (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. NM_144520) produced a luciferase signal over background. Stimulation by the retinoid X receptor α protein may reflect a shortage of this vitamin D receptor heterodimerization partner in the HEK 293 cells. Similarly, enhancement by the hypoxia induction factor 1α is most likely the result of synergism between the receptor and this transcription factor. The mechanism by which the SEC14-related protein stimulated expression remains unknown, but the effect was modest (≤2-fold).

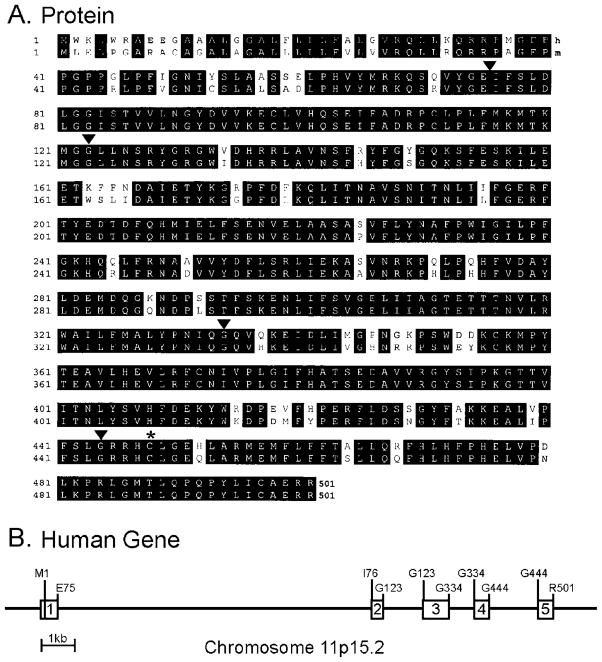

The cDNA in the A11 pool that stimulated vitamin D receptor activity encoded cytochrome P450 2R1 (CYP2R1) based on sequence comparisons among gene family members (drnelson. utmem.edu/CytochromeP450.html). The amino acid sequence of the CYP2R1 protein was deduced from the isolated mouse cDNA (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. AY323818), and the amino acid sequence of the human enzyme (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. AY323817) was generated from a cDNA isolated from liver mRNA using PCR (Fig. 2A). The two enzymes share 89% sequence identity at the amino acid level (Fig. 2A), and the coding regions of the two cDNAs share 89% identity at the nucleic acid level. The human CYP2R1 gene is located on chromosome 11, band p15.2, and contains five exons distributed over ~15.5 kb (Fig. 2B). The mouse Cyp2r1 gene occupies a syntenic location on chromosome 7, band 7E3. The mouse CYP2R1 mRNAs are ~1.6 and 1.1 kb in length, with the larger form being more abundant than the smaller form (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Amino acid sequences and gene structure of cytochrome P450 2R1.

A, the deduced sequences of the human (h) and mouse (m) CYP2R1 proteins are aligned with identities between the two enzymes indicated by black boxes. Amino acids are numbered on the left. Arrowheads above the alignment indicate the positions of introns in the encoding genes. An asterisk indicates the cysteine residue that is predicted to ligand with the heme cofactor. The GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession numbers for the human and mouse CYP2R1 cDNA sequences are AY323817 and AY323818, respectively. B, structure of the human CYP2R1 gene. Exons are indicated by boxes and introns by connecting lines. Amino acids encoded at the beginning and end of the protein are indicated above the gene schematic together with those at exon-intron junctions. The structure of the gene and its indicated chromosomal location were deduced by comparing the sequences of the cloned cDNA to those of the genomic DNA (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession no. NT_009237.15).

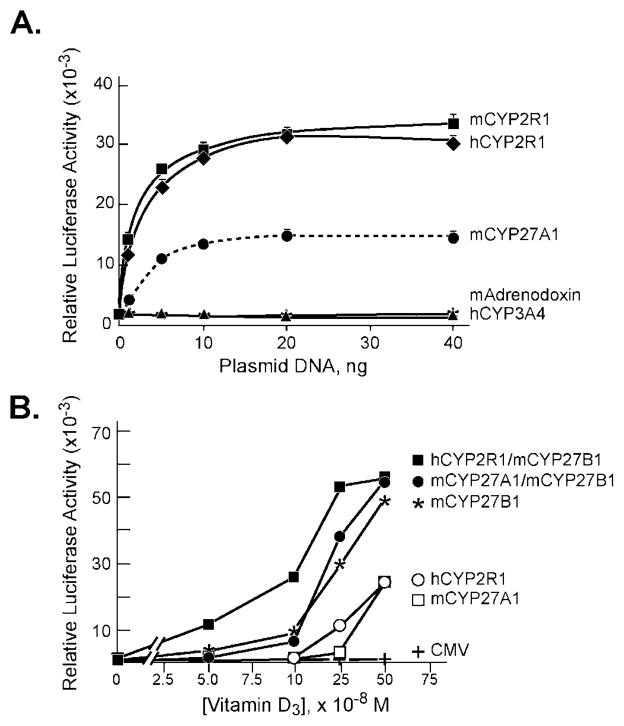

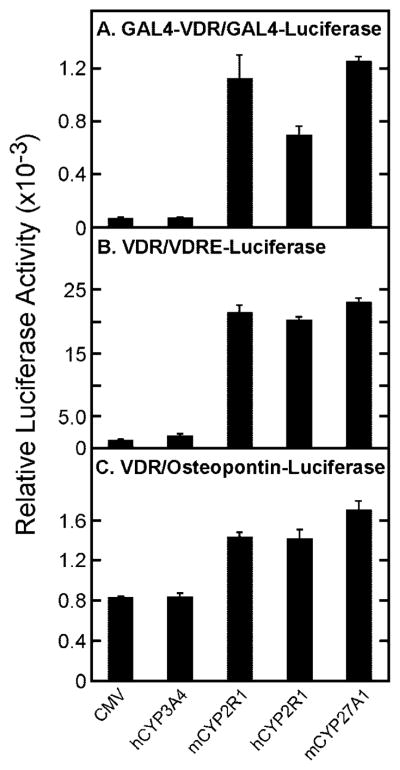

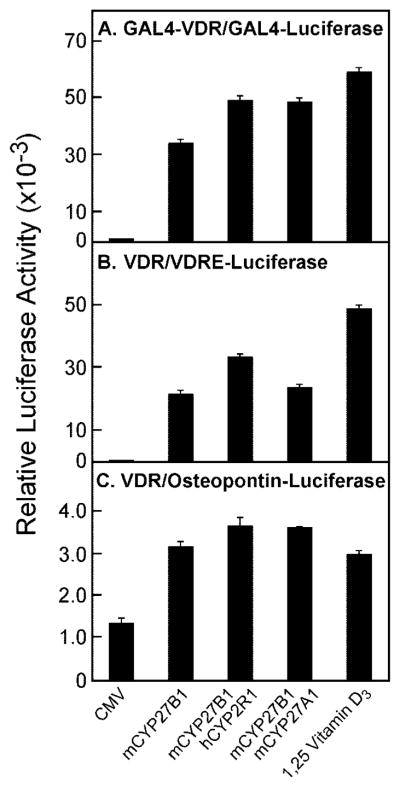

The high degree of sequence conservation between mouse and human CYP2R1 protein sequences, and the ability of this enzyme to activate 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3, suggested that it might be a vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. This hypothesis was tested further in a series of transfection experiments with different cytochrome P450 cDNAs, vitamin D receptor constructs, and reporter genes. Vitamin D3 rather than 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 was utilized as a precursor because 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 also activates the vitamin D receptor, albeit with decreased potency compared with the 1α,25-dihydroxy compound (18). Transfection of the mouse or human CYP2R1 cDNA increased luciferase expression ~7–10-fold in the GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase reporter system (Fig. 3A). A similar stimulation was observed when a plasmid encoding the mouse sterol 27-hydroxylase (mCYP27A1) was introduced into the HEK 293 cells. As negative controls, neither the expression vector alone (pCMV6), nor a vector expressing the human cytochrome P450 3A4 cDNA (hCYP3A4), stimulated the expression of luciferase enzyme activity (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Activation of vitamin D3 by CYP2R1.

The indicated vitamin D receptor-reporter systems were introduced into HEK 293 cells grown in 60-mm dishes together with the expression plasmids designated at the bottom of the figure. Relative luciferase enzyme activity was determined 16–20 h later as indicated under “Experimental Procedures,” and the means ± S.E. for experiments carried out in triplicate were plotted as histograms. The amounts of vitamin D3 added to the medium were 0.5 μM (A and B) and 1 μM (C).

Similar responses were ascertained when the receptor-reporter system was switched to one composed of the intact vitamin D receptor and a luciferase reporter gene driven by three copies of a vitamin D response element from the mouse osteopontin gene linked to a basal TK promoter (Fig. 3B). Plasmids expressing these genes are referred to as the VDR/VDRE-luciferase system. Here, expression of the human or mouse CYP2R1 cDNAs led to marked stimulation of luciferase enzyme activity (16- and 17-fold, respectively), as did expression of the mCYP27A1 cDNA (18-fold).

The final receptor-reporter system tested was composed of the intact vitamin D receptor and a 0.862-kb DNA fragment encompassing the promoter of the mouse osteopontin gene linked to the luciferase reporter gene (VDR/osteopontin-luciferase). Previous studies showed that the osteopontin regulatory sequences contain a bona fide vitamin D-responsive element (36). The basal luciferase expression level observed in this system in the presence of the control CMV or hCYP3A4 plasmids was substantial (Fig. 3C). Nevertheless, transfection of the human or mouse CYP2R1 cDNAs consistently produced a 2–3-fold stimulation of luciferase activity. This level of stimulation by vitamin D3 is similar to that reported in other studies with the osteopontin promoter (36).

We next tested the ability of the CYP2R1 enzymes to work in concert with the CYP27B1 vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase to activate vitamin D precursors. These experiments proved challenging for three reasons. First, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 generated by the CYP27B1 enzyme has some agonist activity on the vitamin D receptor (18). Second, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 generated by the CYP2R1 or CYP27A1 enzymes also has significant agonist activity (Fig. 3). Third, there is a low level of endogenous CYP2R1 enzyme activity expressed in the HEK 293 cells, which is very active against 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 generated in situ following transfection with the CYP27B1 cDNA.

Despite these challenges, informative data were generated in transfection experiments with the various P450 expression vectors. As shown in Fig. 4A, when the GAL4-VDR/GAL4-luciferase system was employed using vitamin D3 as a substrate, transfection of the CYP27B1 1α-hydroxylase cDNA alone led to a 470-fold stimulation of luciferase enzyme activity. This increase presumably represents the synthesis and activation of the receptor by both the 1α-hydroxylated form of vitamin D3 produced by CYP27B1 and the additional 25-hydroxylation of this product by the endogenous CYP2R1. Co-transfection with the CYP27B1 and the human CYP2R1 cDNA increased the level of stimulation to 670-fold, and similar responses were observed when the CYP27B1 and CYP27A1 cDNAs were co-transfected. The latter fold stimulations were roughly equivalent to those measured when cells transfected with the receptor-reporter system alone were incubated with 10 nM 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Fig. 4A). Similar increases were observed when the VDR/VDRE-luciferase and VDR/osteopontin-luciferase systems were used to monitor vitamin D activation (Fig. 4, B and C). The stimuli ascertained upon co-transfection of the vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase and 25-hydroxylase cDNAs were modestly but reproducibly higher than those determined with the vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase cDNA alone.

Fig. 4. Activation of vitamin D3 by cytochrome P450 enzymes.

Plasmids encoding the indicated vitamin D receptor-reporter systems were transfected into HEK 293 cells grown in 60-mm dishes together with DNAs encoding the hydroxylase enzymes shown at the bottom of the figure. Relative luciferase enzyme activity was measured 16–20 h later, and the means ± S.E. of values derived from experiments performed in triplicate were calculated. The amounts of vitamin D3 added to the culture medium were 0.5 μM (A), 0.25 μM (B), and 5 μM (C). 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (0.01 μM) was added in the absence of hydroxylase expression plasmids to control wells for the receptor-reporter systems to generate the data shown by the histogram bars on the right of each panel.

To determine the specificity of CYP2R1, the capacity of the encoded protein to activate or inactivate ligands for other nuclear receptors was determined. Expression of human CYP2R1 cDNA was found to have no effect on the abilities of the following receptor/ligand pairs to stimulate luciferase reporter genes: human thyroid hormone receptor β/triiodothyronine, mouse liver X receptor α/T0901317, human farnesoid X receptor/GW4064, human retinoic acid receptor α/(E)-4-[2-(5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5,5,8,8-tetramethyl-2-naphthylenyl)-1-propenyl]benzoic acid, and mouse peroxisomal proliferator receptor γ/rosiglitazone (data not shown).

The experiments reported in Figs. 3 and 4 used single amounts of CYP expression plasmids and single concentrations of vitamin D3 precursor to demonstrate activation of the receptor-reporter systems. To assess the effects of changing the concentrations of these components, dose-response curves were generated in two different ways. In the first, which utilized the VDR/VDRE-luciferase system, the amount of P450 or control expression plasmid was varied and the level of 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 substrate was held constant. The data from this experiment showed an increase in luciferase enzyme expression with increasing amounts of human or mouse CYP2R1 expression plasmid added to the dish (Fig. 5A). Saturation of the response system was reached when 10 ng of P450 expression plasmid was added to the cells. A similar hyperbolic curve was observed when the mouse CYP27A1 expression plasmid was used but the relative level of enzyme activity measured at saturation was 50% less, which may be a consequence of an intrinsically lower activity of the CYP27A1 enzyme against 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (11). No increase in luciferase enzyme activity was observed when mouse adrenodoxin or human CYP3A4 were expressed in these cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Response of VDR/VDRE-luciferase reporter system to P450 expression vectors and vitamin D3.

A, the indicated amounts of P450 expression plasmids were introduced by transfection with the FuGENE6 reagent into HEK 293 cells grown in 60-mm dishes. Relative luciferase enzyme activities were measured 16–20 h later, and means ± S.E. were calculated from individual experiments performed in triplicate. The concentration of 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 added to the culture medium was 1 nM. B, P450 expression vectors (5–20 ng of plasmid DNA) were transfected into HEK 293 cells grown in 60-mm dishes in medium containing the indicated concentrations of vitamin D3. Relative luciferase enzyme activities were determined 16–20 h later. Mean values based on data from triplicate dishes for each concentration of vitamin D3 were plotted.

In the second experiment, levels of vitamin D3 were varied and the amounts of the P450 expression plasmids were held constant (Fig. 5B). In these experiments, CYP2R1 was more robust than CYP27A1 in generating an active receptor at low levels of vitamin D3, but this difference was lost at higher concentrations of the precursor. Expression of the CYP27B1 1α-hydroxylase led to an even higher level of luciferase enzyme activity for the reasons noted above. The most potent combination of plasmids was composed of the human CYP2R1 and mouse CYP27B1, which generated a measurable luciferase signal at the lowest concentration (50 nM) of vitamin D3 assayed (Fig. 5B).

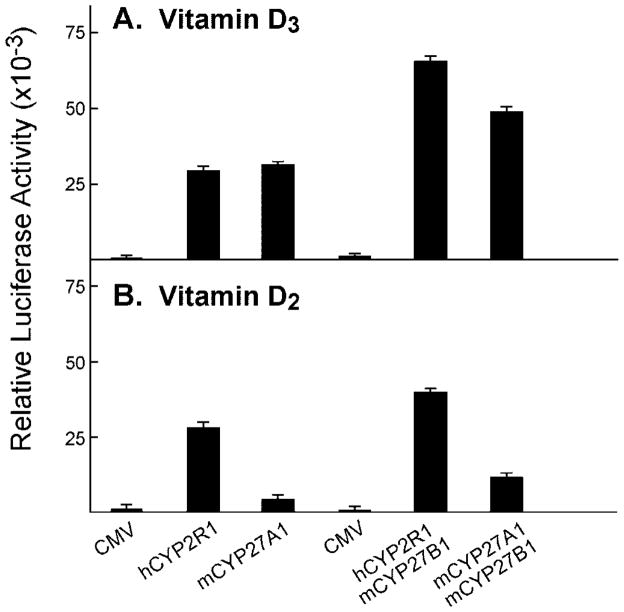

Mitochondrial vitamin D 25-hydroxylase shows a preference for vitamin D3 over vitamin D2 as a substrate (11, 35). This preference, and the well known ability of both secosteroids to fulfill the physiological roles of the vitamin, supports the existence of additional mammalian vitamin D 25-hydroxylases (22). To determine the substrate preference of the CYP2R1 enzyme, activation of both vitamin D precursors was assessed using the VDR/VDRE-luciferase receptor-reporter system. These experiments revealed that the human CYP2R1 activated vitamin D3 and D2 equally well and that, as expected, CYP27A1 showed a preference for vitamin D3 (Fig. 6). This difference in substrate preference also was observed when the 25-hydroxylases were used in combination with the CYP27B1 1α-hydroxylase. No activation of either vitamin D precursor was observed when the cells were transfected with a CMV vector alone (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Activation of vitamin D3 and vitamin D2 by microsomal versus mitochondrial P450 enzymes.

Vectors specifying the VDR/VDRE-luciferase reporter system were introduced into HEK 293 cells grown in 60-mm dishes together with the indicated expression plasmids encoding no protein (CMV) or various vitamin D hydroxylases. Relative luciferase enzyme activities were measured 16–20 h later. The means ± S.E. were calculated for each plasmid or combination of plasmids analyzed in triplicate. A, the concentration of vitamin D3 in the medium of dishes transfected with the CMV, hCYP2R1, and mCYP27A1 plasmids (left three histogram bars) was 0.5 μM, and the concentration in the medium of dishes transfected with CMV, hCYP2R1 + mCYP27B1, and mCYP27A1 + mCYP27B1 plasmids (right three histogram bars) was 0.25 μM. B, the concentration of vitamin D2 in the medium of dishes transfected with the CMV, hCYP2R1, and mCYP27A1 plasmids (left three histogram bars) was 0.5 μM, and that in the medium of dishes transfected with CMV, hCYP2R1 + mCYP27B1, and mCYP27A1 + mCYP27B1 plasmids (right three histogram bars) was 0.1 μM.

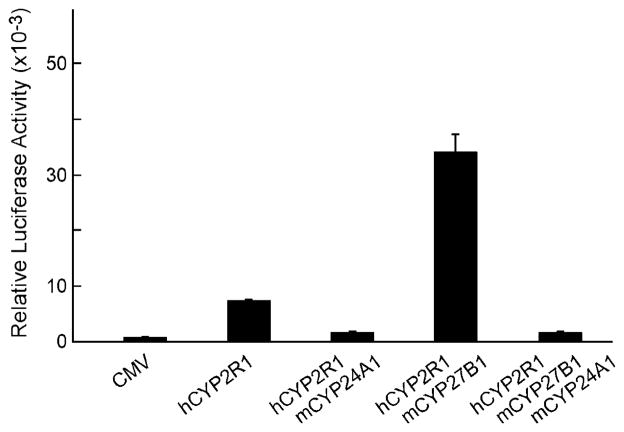

The inactivation of vitamin D is mediated by the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase enzyme, a microsomal P450 (CYP24A1) that is highly selective for this substrate (22). If the activation of vitamin D mediated by the CYP2R1 enzyme was caused by 25-hydroxylation, then co-transfection of a 24-hydroxylase cDNA with the CYP2R1 cDNA should lead to inactivation of the ligand, and a consequent reduction in luciferase enzyme activity. As shown in Fig. 7, co-transfection of HEK 293 cells with the VDR/VDRE-luciferase receptor-reporter system and the 24-hydroxylase cDNA reduced luciferase activity in response to ligand generated from vitamin D3 by the human CYP2R1 enzyme (presumably 25-hydroxyvitamin D3), and by a combination of the CYP2R1 and vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase enzyme (presumably 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3).

Fig. 7. Inactivation of vitamin D metabolites by expression of CYP24A1 vitamin D 24-hydroxylase.

The indicated plasmid or combinations of plasmid DNAs were introduced into HEK 293 cells cultured in 60-mm dishes together with vectors specifying the VDR/VDRE-luciferase reporter system. Vitamin D3 was added to the medium at a final concentration of 0.25 μM, and relative luciferase activity was measured in triplicate dishes 16–20 h later as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Means ± S.E. were calculated and plotted as histograms. Co-expression of the CYP24A1 vitamin D 24-hydroxylase with either the CYP2R1 25-hydroxylase, or a combination of CYP2R1 and the CYP27B1 1α-hydroxylase, led to a reduction of vitamin D receptor activation and lower luciferase enzyme activity.

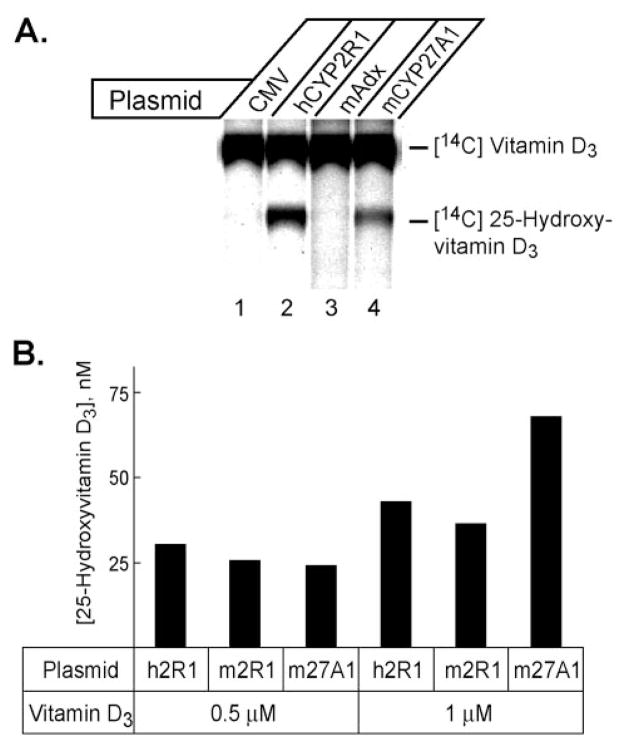

The experiments with the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase expression plasmid suggested that the active vitamin D ligand generated by the CYP2R1 enzyme was 25-hydroxyvitamin D. This interpretation was confirmed in chemical and immunological experiments (Fig. 8A). Transfection of a CYP2R1 cDNA into HEK 293 cells followed by incubation with 14C vitamin D3 led to the synthesis of a radiolabeled product that migrated on a thin layer chromatography plate at the same position as 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Similarly, expression of the sterol 27-hydroxylase, a known vitamin D3 25-hydroxylase, produced an apparently identical product (lane 4). Transfection with the vector alone (lane 1) or with a cDNA encoding mouse adrenodoxin (lane 3) did not lead to synthesis of this product. Similar results were observed when three different solvent systems were used to develop the thin layer chromatography plates (data not shown).

Fig. 8. Biochemical and immunological identification of CYP2R1 vitamin D metabolites.

A, the indicated expression plasmids were introduced into HEK 293 cells cultured in 60-mm dishes. 18 h later, 14C-labeled vitamin D3 was added to the medium, and the incubation continued for an additional 96 h. Vitamin D metabolites were extracted from the medium into 8 ml of chloroform:methanol (2:1), dried under a stream of N2, resuspended in 50 μl of acetone, and separated by thin layer chromatography on silica plates. The plates were dried and subjected to phosphorimage analysis to reveal the locations of radioactivity. The identities of the radiolabeled compounds were determined based on their co-migration with authentic vitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 standards chromatographed in adjacent lanes on the plate. The mAdx plasmid expresses mouse adrenodoxin. B, radioimmunoassay of vitamin D metabolites produced in transfected cells. The indicated plasmid expression vectors were introduced by transfection into HEK 293 cells grown in 96-well microtiter plates. 10 h later, 0.5 or 1 μM vitamin D3 was added to the medium and the incubation continued for an additional 44 h. Thereafter, the medium from replicate wells was pooled and subjected to radioimmunoassay using a kit containing antibodies directed against 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. The values obtained were compared with those of a standard curve to estimate the amount of 25-hydroxyvitamin D produced in duplicate dishes. A background value corresponding to the amount of 25-hydroxyvitamin D detected in the medium from cells transfected with the CMV vector plasmid (17.2 nM) was subtracted from the experimental values and the resulting number plotted as a histogram.

A radioimmunoassay was used to measure the production of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (Fig. 8B). Expression of mouse or human CYP2R1 cDNAs in the presence of 0.5 μM vitamin D3 led to the synthesis of ~25 nM 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. A comparable level of synthesis was measured after expression of the sterol 27-hydroxylase cDNA (Fig. 8B). Doubling the level of vitamin D3 substrate to 1 μM led to a corresponding 2-fold increase in 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 production (to ~50 nmol/liter) with all three cDNAs. In this experiment, the sterol 27-hydroxylase enzyme was more active at higher substrate concentrations than was CYP2R1. Similar results were obtained when the synthesis of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 from 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 was assessed in transfected cells. When the concentration of this substrate added to the medium was 1 nM, cells expressing CYP2R1 produced 0.26 nM 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 versus 0.13 nM for CYP27A1 expressing cells. Taken together, the data shown in Figs. 1–8 indicated that CYP2R1 is a vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.

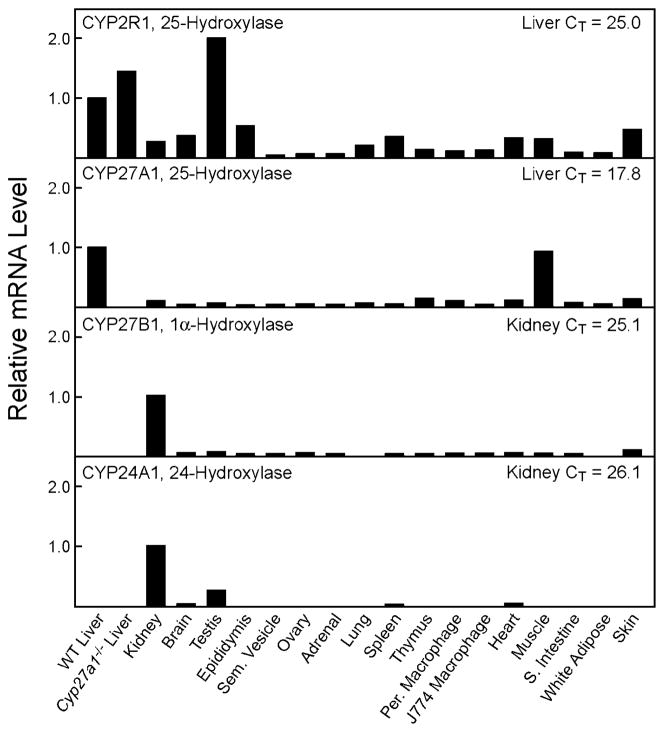

The tissue distribution of the CYP2R1 mRNA was determined in the mouse by real-time PCR and compared with those of the CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase, CYP27B1 vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase, and CYP24A1 vitamin D 24-hydroxylase mRNAs (Fig. 9). These experiments revealed that CYP2R1 mRNA was most abundant in the liver and testis2 and present in lower levels in numerous other tissues and cell types. The CYP27A1 mRNA was present at high levels in liver and muscle, and detectable in all other tissues tested. As expected, the CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 mRNAs were most abundant in the kidney and present in much lower amounts in other tissues. Inasmuch as threshold values (CT) determined for different mRNAs with different primer pairs can be compared, it is interesting to note that the CT values for the CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and CYP24A1 mRNAs in the liver and kidney are in the same range (CT = 25–26), whereas that for the hepatic CYP27A1 mRNA is far higher (CT = ~18). In separate experiments for which the data are not shown, the CT values determined for the CYP2R1 mRNA in male and female mouse liver were 24.7 and 24.6, respectively, indicating the absence of sexual dimorphism in the expression of this gene.

Fig. 9. Tissue distributions of mouse vitamin D hydroxylase mRNAs.

The relative levels of the vitamin D hydroxylase mRNAs were determined by real-time PCR in the tissues and cell types indicated at the bottom of the figure using cyclophilin mRNA levels as a reference standard. The data for a given hydroxylase mRNA were normalized to the threshold (CT) values determined in the liver for the CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 mRNAs (top two panels), and to the kidney CT values for the CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 mRNAs (bottom two panels). WT liver, wild type liver; Cyp27a1−/− Liver, liver of CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase-deficient mice; Sem. Vesicle, seminal vesicle; Per. Macrophage, peritoneal macrophages elicited by a thioglycolate challenge (43); J774 Macrophage, transformed mouse macrophage cells (ATCC no. TIB-67); S. Intestine, small intestine.

DISCUSSION

We report the isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding a vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. Expression cloning using a vitamin D receptor ligand activation assay identified one cDNA from among ~110,000 in a mouse liver library that specified this enzyme activity. DNA sequence analysis revealed a highly conserved orphan cytochrome P450 enzyme, termed CYP2R1, which is predicted to reside in the microsomal membrane. The product of the CYP2R1 enzyme co-migrated with authentic 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 on thin layer chromatography, and was detected in a radioimmunoassay using antibodies directed against 25-hydroxylated forms of vitamin D3. Expression of the CYP2R1 enzyme in cultured cells stimulated the transcriptional activity of the vitamin D receptor in three different reporter gene systems, acted synergistically with the CYP27B1 vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase to produce a more potent ligand, and was antagonized by co-expression of the CYP24A1 vitamin D 24-hydroxylase. Unlike the CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase, which showed specificity for vitamin D3, the CYP2R1 enzyme hydroxylated both vitamin D2 and vitamin D3. CYP2R1 mRNA is present in the liver, where it is predicted to play an important role in the activation of vitamin D.

Studies over the last 30 years identified vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activities in both microsomal (16, 17) and mitochondrial membranes (10) that were associated with cytochrome P450 enzymes. Purification of the mitochondrial protein (12, 13), and subsequent cDNA cloning (14, 15, 37), yielded the CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase, which, in addition to hydroxylating vitamin D, catalyzed 27-hydroxylation of sterol intermediates in the bile acid biosynthetic pathway (38). Anomalies of cholesterol catabolism are a characteristic feature of sterol 27-hydroxylase deficiency in humans and mice, but affected individuals (24) and animals (25) do not exhibit signs of vitamin D insufficiency, suggesting that another enzyme, presumably the microsomal activity, compensates for the loss of CYP27A1-mediated vitamin D 25-hydroxylation.

Several lines of evidence are consistent with the notion that the CYP2R1 enzyme identified here is the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. First, CYP2R1 has characteristic sequence features associated with a P450 of the endoplasmic reticulum, including a hydrophobic amino terminus (Fig. 2), and sequences involved in the interaction with the cytochrome P450 reductase cofactor (39). CYP2R1 does not contain a signature sequence associated with mitochondrial P450 proteins, CXX(R/K)(R/K), which is located toward the carboxyl terminus and includes the cysteine ligand of the heme co-factor (40). The mouse CYP2R1 is 89% identical in sequence to the human enzyme (Fig. 2A), and is conserved through evolution at least through the bony fish Takifugu rubripes (41). Highly conserved P450 enzymes are often those with endogenous substrates, such as sterols, fatty acids, and vitamins, and CYP2R1 fits this pattern. In addition, vitamin D receptor orthologues are reported for several different species of fish, including T. rubripes (GenBank™ accession nos. AF164512, BAA95016, and AJ243956, and Ensemble Gene ID SINFRUG00000063876), suggesting that CYP2R1 may perform a similar activation function in teleosts.

A second line of evidence is that the substrate specificity of CYP2R1 closely resembles that of the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. Experiments in cultured cells with different receptor-reporter systems show that CYP2R1 activates vitamin D2, vitamin D3, and 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (Figs. 3–6). The ability to 25-hydroxylate both ergocalciferol (D2) and cholecalciferol (D3) is a characteristic of the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase but not the mitochondrial CYP27A1 sterol 27-hydroxylase (11). Although the typical order of vitamin D hydroxylation events is thought to be 25-hydroxylation in the liver followed by 1α-hydroxylation in the kidney or other target tissues (22), biochemical data show that the microsomal 25-hydroxylase also is capable of utilizing the 1α-form of the vitamin as a substrate (34).

In several experiments (e.g. Figs. 5B and 8B), the mitochondrial CYP27A1 enzyme was more active at higher concentrations of vitamin D3 substrate than was CYP2R1. This behavior represents a third line of evidence in support of CYP2R1 being the microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase because in vivo data (42) and in vitro data (10, 17, 44) suggest that the mitochondrial hydroxylase is a low affinity, high capacity enzyme, whereas the microsomal hydroxylase is a high affinity, low capacity enzyme. Although the reasons for these apparently different kinetic properties were not determined here, future experiments with the recombinant CYP27A1 and CYP2R1 enzymes should reveal whether they are related to transport of the vitamin into the mitochondrion or microsome, differences in the biochemical characteristics of the two enzymes, or other parameters.

The tissue distribution of the encoding mRNA represents a fourth line of evidence that CYP2R1 is the microsomal 25-hydroxylase (Fig. 7). In the rat, and presumably the mouse, the liver is the major site of vitamin D 25-hydroxylation, as judged by the failure of hepatectomized animals to synthesize this intermediate following intravenous injection of radiolabeled vitamin D (2, 3). In agreement with this tissue selectivity, CYP2R1 mRNA is most abundant in the liver (CT ~ 24.9; Fig. 7). The mRNA is present also in the testis at similar levels (CT ~25.0),2 and in lower amounts in other organs and cell types. Not all mRNAs present in the testis are translated (45), and we have not been successful in raising antibodies directed against the CYP2R1 protein to determine whether the enzyme is present in this tissue. Furthermore, the experimental design used to detect hepatic 25-hydroxyvitamin D synthesis noted above may have missed interconversion in the testis as a result of the blood-testis barrier (46). For these reasons it is not clear whether CYP2R1 enzyme activity is expressed in the testis, or if it is, what the physiological significance of this expression might be.

Several microsomal P450 enzymes with vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activity have been identified in other species (47). For example, rat CYP2C11 is a male-specific enzyme with this activity but is unique to this species and does not act on vitamin D2 (48, 49). Pig CYP2D25 25-hydroxylates both vitamin D2 and D3 but there is no corresponding orthologue for this P450 in humans (50). The human CYP2D6 protein shares the greatest sequence identity (77%) with the pig CYP2D25, but the CYP2D6 enzyme does not possess vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activity (50). In contrast to these findings, the CYP2R1 enzyme reported here is not sexually dimorphic, is conserved from fish to humans, and acts on both forms of vitamin D. Sequence identity between the human CYP2R1 and these other rat, pig, and human vitamin D 25-hydroxylase enzymes varies between 33 and 39%, as would be expected from their inclusion in the CYP2 family (51). In addition, the human CYP2R1 sequence shares little identity with a P450 enzyme isolated from the bacterium Amycolata autotrophica, which has vitamin D 25-hydroxylase activity (52). Whether the limited sequence identity between these enzymes can be used to reveal important features of the substrate binding domain remains to be determined in structure-function studies.

The existence of two enzymes in humans and mice capable of 25-hydroxylating vitamin D raises the question: what are the relative contributions of CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 to activation? In attempting to answer this question, it is partially instructive to compare the specific activities of 25-hydroxylation in the microsomal and mitochondrial fractions. Values for these activities were reported by Bjorkhem and Holmberg (10), who used a quantitative mass spectrometry-based assay to determine a specific activity ranging from 48 to 157 pmol of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 formed/45 min for the microsomal enzyme, and from 95 to 270 pmol/45 min for the mitochondrial enzyme. Assuming a one-to-one correspondence between these activities and the production of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in vivo suggests that the microsomal enzyme is responsible for ~30% of total activity and the mitochondrial enzyme 70%. A comparison of CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 mRNA levels provides further insight into this question. As determined in real-time PCR experiments, the CT value for CYP2R1 mRNA in liver was ~24.9, whereas that for the CYP27A1 mRNA was ~17.8 (Fig. 7). This result indicates again that CYP27A1 is the more abundant enzyme in the liver.

Extrapolation of these data, which suggest that CYP27A1 synthesizes a majority of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, to the in vivo production of the transformed vitamin must be done with caution. The biochemical measurements assume the absence of inhibitors in the crude membrane fractions used in the assay, equal accessibility to an otherwise hydrophobic substrate, and similar stabilities of the two enzymes following subcellular fractionation. The mRNA measurements assume the absence of post-transcriptional and translational control, equal amplification efficiencies of the primer pairs used in the PCR assay, and that both mRNAs are targeted to their respective membrane compartments with parity. Although these caveats prevent a definitive answer to the question of the relative contributions of CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 to vitamin D 25-hydroxylation, it is clear from analysis of humans (24, 25) and mice (25) deficient in sterol 27-hydroxylase that the microsomal activity, which the current data suggest is CYP2R1, is able to fulfill this biological role. We are in the process of constructing mice with mutations in the CYP2R1 gene to gain further insight into the role of this P450 in vitamin D activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daphne Davis, Tina Hoang, and Linda Donnelly for excellent technical assistance; Andrew Shulman for nuclear receptor plasmids and Joe Zerwekh for radiolabeled vitamin D; Bill Peterson for discussions concerning P450 enzyme structure; and Helen Hobbs for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL20948 (to D. W. R.), a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to D. J. M.), and Robert A. Welch Foundation Grants I-0971 (to D. W. R.) and I-1275 (to D. J. M.).

The abbreviations used are: CYP, cytochrome P450; Adx, adrenodoxin; h, human; m, mouse; GAL4, galactose 4; VDR, vitamin D receptor; VDRE, vitamin D response element; TK, thymidine kinase; HEK, human embryonic kidney; CT, threshold value; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

The CT values for CYP2R1 mRNA in the liver and testis were both 24.9. The apparent 2-fold difference in the relative levels of this mRNA between the two tissues shown in Fig. 7 arises as a result of the method of normalization (2e−ΔΔCT), which uses the amount of cyclophilin mRNA as a divisor.

References

- 1.Simoni RD, Hill RL, Vaughan M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponchon G, DeLuca HF. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1273–1279. doi: 10.1172/JCI106093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponchon G, Kennan AL, DeLuca HF. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:2032–2037. doi: 10.1172/JCI106168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blunt JW, DeLuca HF, Schnoes HK. Biochemistry. 1968;7:3317–3322. doi: 10.1021/bi00850a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haussler MR, Myrtle JF, Norman AW. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:4055–4064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick MF, Schnoes HK, DeLuca HF, Suda T, Cousins RJ. Biochemistry. 1971;10:2799–2804. doi: 10.1021/bi00790a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser DR, Kodicek E. Nature. 1970;228:764–766. doi: 10.1038/228764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haussler MR, Norman AW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;62:155–162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell DP, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pike JW, Haussler MR, O’Malley BW. Science. 1987;235:1214–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.3029866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjorkhem I, Holmberg I. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:842–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo YD, Strugnell SA, Back DW, Jones G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8668–8672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlback H, Wikvall K. Biochem J. 1988;252:207–213. doi: 10.1042/bj2520207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masumoto O, Ohyama Y, Okuda K. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su P, Rennert H, Shayiq RM, Yamamoto R, Zheng Y, Addya S, Strauss JF, III, Avadhani NG. DNA Cell Biol. 1990;9:657–665. doi: 10.1089/dna.1990.9.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usui E, Noshiro M, Okuda K. FEBS Lett. 1990;262:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80172-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharyya MH, DeLuca HF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;160:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(74)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madhok TC, DeLuca HF. Biochem J. 1979;184:491–499. doi: 10.1042/bj1840491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeyama K, Kitanaka S, Sato T, Kobori M, Yanagisawa J, Kato S. Science. 1997;277:1827–1830. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohyama Y, Noshiro M, Okuda K. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80115-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen KS, Prahl JM, DeLuca HF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4543–4547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh S, Yoshimura T, Iemura O, Yamada E, Tsujikawa K, Kohama Y, Mimura T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1264:26–28. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones G, Strugnell SA, DeLuca HF. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1193–1231. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cali JJ, Hsieh C, Francke U, Russell DW. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7779–7783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjorkhem I, Boberg KM, Leitersdorf E. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, editors. McGraw-Hill, Inc; New York: 2001. pp. 2961–2988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen H, Reshef A, Maeda N, Lippoldt A, Shpizen S, Triger L, Eggertsen G, Bjorkhem I, Leitersdorf E. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14805–14812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repa JJ, Lund EG, Horton JD, Leitersdorf E, Russell DW, Dietschy JM, Turley SD. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(39):685–639. 692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willy PJ, Umesono K, Ong ES, Evans RM, Heyman RA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1033–1045. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.9.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund EG, Kerr TA, Sakai J, Li WP, Russell DW. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34316–34348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu TT, Makishima M, Repa JJ, Schoonjans K, Kerr TA, Auwerx J, Mangelsdorf DJ. Mol Cell. 2000;6:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider RJ, Shenk T. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:317–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi M, Yamamoto KR, Itoh T, Makishima M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Moras D, DeLuca HF, Yamada S. Chem Biol. 2003;10:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makishima M, Lu TT, Xie W, Whitfield GK, Domoto H, Evans RM, Haussler MR, Mangelsdorf DJ. Science. 2002;296:1313–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.1070477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Touchstone JC. Practice of Thin Layer Chromotography. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saarem K, Pedersen JL. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;840:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmberg I, Berlin T, Ewerth S, Bjorkhem I. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1986;46:785–790. doi: 10.3109/00365518609084051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barletta F, Freedman LP, Christakos S. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:301–314. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.2.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson S, Davis DL, Dahlback H, Jornvall H, Russell DW. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8222–8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell DW. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:137–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterson JA, Graham SE. Structure. 1998;6:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham SE, Peterson JA. Methods Enzymol. 2002;357:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)57661-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson DR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;409:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukushima M, Susuki Y, Tohira Y, Nishi Y, Susuki M, Sasaki S, Suda T. FEBS Lett. 1976;65:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edelson PJ, Zweibel R, Cohn ZA. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1150–1164. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.5.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjorkhem I, Holmberg I, Oftebro H, Pedersen JI. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(5):244–245. 249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleene KC. Mech Dev. 2001;106:3–23. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setchell BP, Waites GMH. In: Handbook of Physiology. Greep RO, Astwood EB, editors. V. American Physiological Society; Washington, D. C: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nebert DW, Russell DW. Lancet. 2002;360:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersson S, Holmberg I, Wikvall K. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6777–6781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersson S, Jornvall H. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(16):932–916. 936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosseinpour F, Wikvall K. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34, 650–634, 655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson DR, Koymans L, Kamataki T, Stegeman JJ, Feyereisen R, Waxman DJ, Waterman MR, Gotoh O, Coon MJ, Estabrook RW, Gunsalus IC, Nebert DW. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:1–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawauchi H, Sasaki J, Adachi T, Hanada K, Beppu T, Horinouchi S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]