Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The present study examined correlates of bicycle ownership, bicycling frequency, and projected increases in cycling if perceived safety from cars was improved.

METHODS

Participants were 1,780 adults aged 20–65 recruited from the Seattle, WA and Baltimore, MD regions (48% female; 25% ethnic/racial minority) and studied 2002–2005. Bicycling outcomes were assessed by survey. Multivariable models were conducted to examine demographic and built environment correlates of bicycling outcomes.

RESULTS

About 71% of the sample owned bicycles, but 60% of those did not report cycling. Among bicycle owners, frequency of riding was greater among young, male, white, educated, and lean subgroups. Neighborhood walkability measures within 1km were not consistently related to bicycling. For the whole sample, bicycling at least once per week was projected to increase from 9% to 39% if bicycling was safe from cars. Ethnic-racial minority groups and those in the least safe neighborhoods for bicycling had greater projected increases in cycling if safety from traffic was improved.

CONCLUSION

Implementing measures to improve bicyclists’ safety from cars would primarily benefit racial-ethnic groups who cycle less but have higher rates of chronic diseases, as well as those who currently feel least safe bicycling.

Keywords: active transportation, physical activity, non-communicable diseases, health promotion, built environment, policy

Introduction

Bicycling is the least-used mode of transportation in the United States, but more bicycling could yield health and environmental benefits (Pucher et al., 2010a; Pucher & Buehler, 2012). At 1% of all trips, bicycling rates in the US are among the lowest in the world (Pucher et al., 2010a; Reynolds et al., 2009). Improved understanding of factors related to bicycling could provide an empirical basis for effective interventions targeted at populations who could benefit most. Access to a bicycle is the top predictor of bicycling for transportation (Cao et al., 2009; Pucher et al., 2010b). Fear of injury from cars is a major determinant of cycling decisions (Dill 2009; Handy et al., 2002; Pucher & Buehler, 2012; Shenassa et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2007). Living in a walkable neighborhood is correlated with cycling (Dill & Carr, 2003; Krizek et al., 2009; Nelson & Allen, 1997; Reynolds et al., 2009; Van Dyck et al., 2010).

The aims of the present cross-sectional study were to: (1) evaluate environmental and demographic correlates of bicycle ownership and current bicycling frequency, and (2) assess the correlates of self-projected increases in cycling if safety from cars was improved.

METHODS

Study Design

The present paper used data from the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study (NQLS), an observational study conducted from 2002 to 2005 in King County-Seattle, WA and Baltimore, MD-Washington DC regions. NQLS compared physical activity and health outcomes of residents of neighborhoods that differed on “walkability” and census-based median household income. Details of study design, neighborhood selection, and participant recruitment have been reported (Frank et al., 2010; Sallis et al., 2009) but are summarized here. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at participating academic institutions, and participants gave written informed consent.

Neighborhood Selection

A “walkability index” was computed (Frank et al., 2010) as a weighted sum of four standardized measures in geographic information systems (GIS) at the census block group level: (a) net residential density; (b) retail floor area ratio (retail building square footage divided by retail land square footage, with higher values reflecting pedestrian-oriented design); (c) land use mix (diversity of 5 types of land uses); and (d) intersection density. The walkability index has been related to total physical activity and walking for transportation (Owen et al., 2007; Sallis et al., 2009).

Block groups were ranked by walkability index separately for each region, then divided into deciles. Deciles were used to define “high” versus “low” walkability areas. Block groups were ranked on census-defined median household income, deciled, and deciles were used to define "high" versus "low" income areas. The “walkability” and “income” characteristics of each block group were crossed (low/high walkability × low/high income) to identify block groups that met definitions of study “quadrants.” Contiguous block groups were combined to approximate "neighborhoods", and 32 total neighborhoods (8 per quadrant) were selected.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the selected neighborhoods, with study eligibility established by age (20–65 years), not living in a group establishment, ability to walk, and capacity to complete surveys in English. Participants were contacted for recruitment by mail and telephone in random order within study neighborhoods (balanced by quadrant). All study materials were sent by mail, with an option to complete surveys online or return by mail (Sallis et al., 2009). A total of 2,199 participants completed an initial survey, and n = 1,745 (79%) of these returned a second survey six months later. Because the bicycling-related items were in the second survey, the sample for present analyses was 1,745.

About half of the sample were men (51.7%), and the mean age was 46 years (SD=10.6). The majority of participants identified themselves as Caucasian (75.1%, White non-Hispanic), with other groups including African Americans (12.1%), Asian Americans (5.6%), and Hispanic/Mexican/Latin American (3.3%). BMI ranged from 15.0 to 62.6 (M=26.7, SD=5.5). The sample was well educated with only 8% having a high school education or less, 24.7% with some college, 34.6% with a college degree, and 32.7% with a graduate degree.

Measures

Bicycling behavior and perception

Access to a bicycle in the home, yard, or apartment complex was assessed by one item in a yes/no format (Sallis et al., 1997). Bicycling frequency questions were based on a previous study and excluded stationary biking (Frank et al., 2001). Biking frequency was assessed through the question, “How often do you bicycle, either in your neighborhood or starting from your neighborhood?” (Frank et al., 2001). Five response options ranged from “never” to “every day”. An additional question was developed by NQLS researchers: “How often would you bike if you thought it was safe from cars?” Response options were the same as for current bicycling frequency. Projected changes in bicycling frequency if participants thought riding was safe from cars was computed by “frequency if safer” minus “current frequency”.

Objective environment – walkability

The GIS-based block group walkability procedures for neighborhood selection (described above) were modified to construct GIS walkability measures for each participant using a 1000-meter street network buffer around the residence (Saelens et al., 2012; Frank et al., 2010). The four components, along with the walkability index, were analyzed, all at the individual level.

Perceived environment survey

The Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS) assessed perceived environmental variables thought to be related to physical activity (Saelens et al., 2003). Test–retest reliability and validity of NEWS have been supported (Brownson et al., 2004; De Bourdeaudhuij et al., 2003; Saelens et al., 2003). Eight established subscales were analyzed: residential density, land use mix-diversity, land use mix-access, connectivity, pedestrian/bicycling facilities, aesthetics, safety from traffic, safety from crime. All subscales were coded so higher scores were expected to be related to more physical activity.

Four items within the NEWS with particular relevance to bicycling were selected for exploratory analyses based on previous findings (Moritz, 1998; Vernez-Moudon et al., 2005; Wardman et al., 2007): “parking is difficult in local shopping areas,” “neighborhood streets are hilly, making walking difficult,” “bike/pedestrian trails are easy to get to,” “it is safe to bike in my neighborhood.” Response options were strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). For comparability to previous studies, these items were also retained in the original subscales.

Body mass index (BMI)

Self-reported weight in kilograms and height in meters were used to calculate BMI = weight/height2.

Demographic variables

Region (Seattle/King County or Maryland/Washington, DC region), gender, age, education level, ethnicity, marital status, and number of vehicles per adult in the household were included as covariates.

Data Analysis

SPSS version 17.0 was used for analyses. Because the study design involved recruitment of participants clustered within 32 neighborhoods pre-selected to fall within the quadrants representing high/low-walkability by high/low-income, intraclass correlations (ICCs) reflecting any covariation among participants clustered within the same neighborhoods were computed for the bicycling frequency measures. The ICCs were very near or equal to zero: current biking frequency, ICC = 0.011; biking frequency if safer from cars, ICC = 0.000; and difference score (i.e., difference between current biking frequency and frequency if safer from cars), ICC = 0.009. Because the ICCs were zero or almost zero, negligible random clustering effects were expected, and traditional regression procedures were used.

All variables were treated as continuous/ordinal except bicycle ownership (yes/no) and five demographic variables: region, sex, ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, vs. Other), education (at least a college degree, vs. less than a college degree), and marital status (married or cohabiting vs. other).

The first group of analyses examined all environmental and demographic variables by bike ownership. Binary logistic regression was used to identify significant associations with bike ownership in separate models for each potential correlate.

The second set of analyses used linear regression procedures to examine bivariate correlates of the bicycling frequency outcomes: (a) frequency of biking (bike owners only) and (b) self-projected change (difference score) in bicycling frequency if participants thought riding was safe from cars. Although these outcome variables were somewhat skewed (+2.0 and +1.0, respectively), these skewness values fall within ranges of commonly used rules of thumb, especially when using ANOVA/regression procedures that are considered robust to non-normality (van Belle G., 2002, p. 10). Thus, it was judged preferable to retain the original units (e.g., 5-point ordinal categories) rather than transform the ordinal categories to log-units. Each environmental and demographic correlate was examined in separate analyses.

The third group of analyses investigated whether variables significant (p<.10) in bivariate analyses remained significant (p ≤.05) in multivariable regression models. Multivariable binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the correlates of bike ownership; and multivariable linear regression models evaluated riding frequency (bicycle owners only), and projected change in biking if it was safe from cars (entire sample). Backwards elimination procedures were used to remove the non-significant correlates.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents bivariate correlates of the three bicycling variables. Table 2 presents three multivariable models with variables that remained independently significant (p<.05) across the bicycling variables.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlates of bike ownership (full sample n=1,745), current riding frequency in bike owners (n=1,237), and projected difference in riding frequency if safety from cars improved (full sample n=1,745) ‡. Seattle, WA and Baltimore MD regions, 2002–2005.

| Logistic Regressions |

Linear Regressions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bike Ownership: yes or no |

Riding Frequency of bike owners |

Difference in frequency with improved safety |

||||||

| Odds Ratio |

p | B* | Partial Eta2 |

p | B* | Partial Eta2 |

p | |

| Demographic Variables | ||||||||

| Region (Baltimore or Seattle) A | 1.631 | <.001 | (+) | <.001 | .645 | (+) | <.001 | .995 |

| Age | 0.978 | <.001 | (−) | .008 | .002 | (−) | <.001 | .380 |

| number of vehicles per adult | 1.762 | <.001 | (−) | <.001 | .620 | (−) | .003 | .026 |

| BMI | .956 | <.001 | (−) | .024 | <.001 | (+) | <.001 | .498 |

| Sex B | 1.172 | .134 | (+) | .034 | <.001 | (−) | .001 | .214 |

| Ethnicity C | 1.884 | <.001 | (+) | .021 | <.001 | (−) | .004 | .010 |

| Education D | 1.739 | <.001 | (+) | .008 | .002 | (−) | <.001 | .043 |

| Marital Status E | 2.654 | <.001 | (+) | .002 | .172 | (−) | .017 | .003 |

| Environmental Variables | ||||||||

| Parking is difficult in local shopping areas | .904 | .067 | (+) | .002 | .097 | (+) | .003 | .034 |

| Neighborhood streets are hilly, walking is difficult | 1.080 | .149 | (−) | .001 | .219 | (−) | <.001 | .614 |

| Bike/pedestrian trails are easy to get to | 1.185 | <.001 | (+) | .016 | <.001 | (−) | .001 | .164 |

| Safe to ride bike in neighborhood | 1.291 | <.001 | (+) | .033 | <.001 | (−) | .017 | <.001 |

| Residential Density F | .996 | <.001 | (+) | .002 | .168 | (+) | <.001 | .919 |

| Land use mix-diversity F | 1.161 | .013 | (+) | .006 | .005 | (−) | <.001 | .922 |

| Land use mix-access F | 0.985 | .864 | (+) | .009 | .001 | (+) | <.001 | .895 |

| Street connectivity F | 0.930 | .379 | (+) | .004 | .025 | (+) | .002 | .069 |

| Walking/cycling facilities F | 1.059 | .464 | (+) | .016 | <.001 | (−) | .003 | .028 |

| Neighborhood aesthetics F | 1.442 | <.001 | (+) | .008 | .002 | (−) | .001 | .120 |

| Pedestrian/traffic safety F | 1.593 | <.001 | (+) | .008 | .001 | (−) | .009 | <.001 |

| Safety from Crime F | 1.563 | <.001 | (+) | .003 | .043 | (−) | .009 | <.001 |

| Net Residential Density (lntransformed) G | 0.700 | <.001 | (+) | .001 | .246 | (+) | .001 | .305 |

| Intersection density G | 0.996 | .049 | (+) | .002 | .126 | (+) | .002 | .048 |

| Retail floor area ratio G | 0.632 | .001 | (+) | .004 | .031 | (+) | .002 | .069 |

| Mixed Use G | 0.523 | .007 | (+) | .002 | .083 | (+) | <.001 | .532 |

| Walkability Index | 0.939 | <.001 | (+) | .004 | .020 | (+) | .002 | .067 |

Because a small number of participants skipped one or more survey items, n’s for some analyses are reduced by 1–18 cases.

“B” Is the sign of the B Coefficient, indicating the direction of the relationship.

0 = Baltimore/MD (reference category); 1 = Seattle, WA.

0 = Female (reference category); 1 = Male.

0 = Other Ethnoracial Groups (reference category); 1 = White Non-Hispanic.

0 = Less than a college degree (reference category); 1 = College degree or more.

0 = Not married or living with a partner (reference category); 1 = Married or living with a partner.

Measures derived from the self-reported Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS)

Component measures of the GIS-based Walkability Index.

Table 2.

Multivariable regressions of bike ownership, current riding frequency in bike owners, and projected difference in riding frequency if safety from cars improved. Seattle, WA and Baltimore MD regions, 2002–2005.

| Multivariable Logistic Regression Model |

Multivariable Linear Regression Models | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bike Ownership: yes or no (n = 1,706) |

Riding Frequency of bike owners (n = 1,209) |

Difference in frequency with improved safety (n = 1,698) |

||||||

| Odds Ratio |

p | B* | Partial Eta2 |

p | B* | Partial Eta2 |

p | |

| Demographic Variables | ||||||||

| Region (Baltimore or Seattle) A | 1.463 | .002 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Age | .976 | <.001 | (−) | .010 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| number of vehicles per adult | 1.442 | .002 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| BMI | .977 | .023 | (−) | .017 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Sex B | -- | -- | (+) | .034 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Ethnicity C | 1.445 | .007 | (+) | .014 | <.001 | (−) | .004 | .007 |

| Education D | 1.383 | .009 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Marital Status E | 2.081 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Environmental Variables | ||||||||

| Parking is difficult in local shopping areas | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Neighborhood streets are hilly, walking is difficult | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Bike/pedestrian trails are easy to get to | -- | -- | (+) | .005 | .015 | -- | -- | -- |

| Safe to ride bike in neighborhood | -- | -- | (+) | .015 | <.001 | (−) | .017 | <.001 |

| Residential Density F | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Land use mix-diversity F | 1.355 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Land use mix-access F | -- | -- | (+) | .006 | .008 | -- | -- | -- |

| Street connectivity F | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | (+) | .003 | .018 |

| Walking/cycling facilities F | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Neighborhood aesthetics F | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Pedestrian/traffic safety F | 1.419 | .005 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Safety from crime F | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Net residential Density (lntransformed)G | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Intersection density G | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Retail floor area ratio G | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Mixed Use G | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Walkability Index | .933 | .051 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

“B” Is the sign of the B Coefficient, indicating the direction of the relationship.

0 = Baltimore/MD (reference category); 1 = Seattle, WA.

0 = Female (reference category); 1 = Male.

0 = Other Ethnoracial Groups (reference category); 1 = White Non-Hispanic.

0 = Less than a college degree (reference category); 1 = College degree or more.

0 = Not married or living with a partner (reference category); 1 = Married or living with a partner.

Measures derived from the self-reported Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS)

Component measures of the GIS-based Walkability Index.

Correlates of Bicycle Access/Ownership

Approximately 71% of participants reported access to a bicycle (i.e., owners). In multivariable models (Table 2), the odds of bicycle ownership were lower for higher age and BMI. Odds of ownership were higher for those living in the Seattle/King Country region, White non-Hispanics, those with a college degree, married or living with a partner, and higher vehicle-to-adult ratios. Among environmental variables, odds of owning a bike were greater for participants who reported higher pedestrian safety from traffic and land use mix-diversity. Higher objective walkability was associated with slightly lower odds of bike ownership.

Correlates of Bicycling Frequency

Of the 1,237 participants with bike access, all but two had complete data for bike riding frequency. The majority of bike owners reported never riding (60.3%), while 27.7% rode less than once a week, and 12% rode at least once per week. In multivariable models for bicycling frequency, male bike owners, younger bike owners, and those with lower BMI rode bikes more often. Other racial-ethnic group bike owners rode less often than White non- Hispanic owners. Reported environmental correlates associated with a higher riding frequency included having bike/pedestrian trails easy to get to, greater safety for riding in the neighborhood, and greater land use mix-access. No objective neighborhood measure retained significance in the multivariable model.

Correlates of Self-Projected Bicycling If Safety from Cars Was Improved

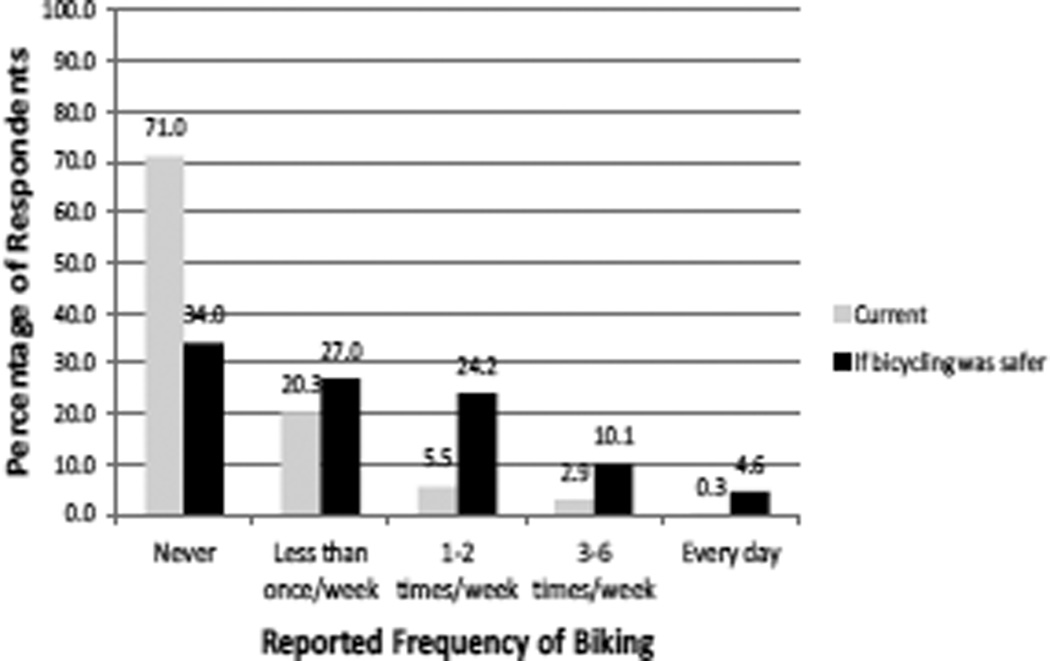

Figure 1 contrasts the distributions of current bicycling frequency and projected frequency if safe from cars. The paired t-test was highly significant (t=34.16, df=1734, p<.001). The mean projected increase (difference score) in bicycling if safe from cars was 0.83 (SD=1.01) on a 5-point scale for the total sample (p<.001) and was similar for bicycle owners (0.84 increase) and non-owners (0.81 increase). As shown in Figure 1, the percent never riding was projected to decrease from 71% to 34%, and the percent riding at least once per week was projected to increase from 8.7% to 38.9%.

Figure 1.

Distribution of bicycling frequency for the total sample currently and projected if safety from traffic was improved. Seattle, WA and Baltimore MD regions, 2002–2005.

Table 3 shows the distribution of projected changes in riding frequency by baseline bicycle access and each level of riding frequency. Except for those who rode the most, there were substantial projected increases in bicycle riding frequency in each group based on current riding frequency. Notably, about 44% of non-owners said they would ride more than once per week, and 59% of owners who never rode said they would ride more if safety improved.

Table 3.

Projected changes to baseline riding frequency if safety improved. Reported as %. Seattle, WA and Baltimore MD regions, 2002–2005.

| Riding frequency if safety improved… |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every day | 3.8 | 1.5 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 18.8 | 100.0 |

| 3–6× week | 6.7 | 6.2 | 9.1 | 28.0 | 81.3 | 0.0 |

| 1–2× week | 17.0 | 20.5 | 37.5 | 58.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| <1× week | 16.2 | 30.9 | 45.2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Never | 56.3 | 40.9 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Non- Owners (n=506) |

Never (n=741) |

<1× week (n=341) |

1–2× week (n=93) |

3–6× week (n=48) |

Every day (n=6) |

|

| Bike Owners (n=1229) | ||||||

In the multivariable linear model for projected increase in riding frequency if safety improvements were made (Table 2), race-ethnicity was the only significant demographic correlate (greater increase for non-Whites). Higher scores for neighborhood safety for riding were associated with lower projected changes in riding frequency. Reported street connectivity, however, was associated with higher projected changes in riding frequency. Objective built environment features were unrelated to projected changes in riding frequency.

DISCUSSION

Although 71% of participants had access to a bicycle, 60% of owners reported never riding. Because concern about traffic danger was previously reported as the major barrier to bicycling (Dill, 2009; Handy et al., 2002; Shenassa et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2007), all participants were asked to project how much they would bicycle if they thought they were safe from cars. Considering both bicycle owners and non-owners, the projected percent who never rode might decrease from 71% to 34%, and the percent who would ride at least weekly might increase from about 9% to 39%. Improving safety from cars has the potential to attract many new riders, because about 44% of non-owners and 59% of owners who never rode stated they would start riding at least once per week. Although these projected increases may not translate exactly into behavior change, the large self-projected increases imply that interventions to improve safety from cars have the potential to substantially increase the number of bicyclists and their frequency of bicycling. One recommendation is to make efforts to protect bicyclists from cars a central goal of multi-strategy bicycle interventions.

Improving safety from traffic might provide the most benefits to those most in need. Multivariable analyses showed non-whites (including Hispanics), those who perceive their neighborhoods as least safe for bike riding, and those reporting higher street connectivity would have larger projected increases in cycling if they felt safe from traffic. Most of these variables were correlated with lower current frequency of cycling. Targeting traffic safety and bicycle infrastructure interventions to racial-ethnic minority neighborhoods and areas that are least safe for bicycling could be expected to be effective and cost-efficient.

In general, bicycle owners appeared to be affluent and have demographic profiles consistent with a low risk of chronic diseases (LaVeist, 2005), compared to non-owners. Bicycle owners were more likely to live in places rated better for pedestrian safety. Though places that are safe from traffic may encourage people to purchase bicycles, the role of walkability, if any, is unclear.

Neighborhood environment characteristics were not strong or consistent correlates of bicycling frequency. This may be due to lack of detailed assessment of bicycling facilities such as separated bike paths. There also is a mismatch in scale, with environmental variables assessed within 1 km or a 15-minute walk, but bicycle trips are often much longer (Dill, 2009; USDOT 2010). Thus, attributes of the immediate neighborhood may not be important for bicycling because most bicycle trips go well beyond the neighborhood.

Other studies found consistent and similar demographic correlates and inconsistent environmental correlates of bicycling (Vernez-Moudon et al., 2005). Limitations of the present study were that survey items did not distinguish bicycling for transportation vs. recreation, unknown accuracy of recall of bicycling frequency, no detailed assessment of bicycle facilities or policies, speculative nature of projected increases, and the cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

Though about 70% of the adult sample had access to bicycles, most reported never riding. Bicycling is currently benefitting subgroups at lower risk of chronic disease, such as young, lean, males, and whites. Safety when bike riding was a correlate of bicycling frequency, and participants projected they would bicycle much more if they thought biking was safe from cars. Half or more of those who did not own bikes and owners who never rode projected they would start riding if safety improved, and many of those who already rode projected they would ride more often. Improving safety from traffic may be most effective for racial-ethnic minorities and those who perceive their neighborhoods as least safe. Thus, targeting traffic calming, bicycle facilities, and other interventions to the least-safe neighborhoods could be an effective and efficient approach to increase bicycling and improve health among subgroups at generally higher risk for chronic diseases.

HIGHLIGHTS.

About 70% of adults had access to bicycles, but most reported never riding.

Half of those who never rode projected they would start riding if safety improved.

Traffic safety interventions should be targeted to the least-safe neighborhoods.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant HL67350. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Carrie Geremia and Brooks LeComte in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the present paper.

Contributor Information

James F. Sallis, Email: jsallis@ucsd.edu.

Terry L. Conway, Email: tlconway@ucsd.edu.

Lianne I. Dillon, Email: liannedillon@gmail.com.

Lawrence D. Frank, Email: ldfrank@exchange.ubc.ca.

Marc A. Adams, Email: marc.adams@asu.edu.

Kelli L. Cain, Email: kcain@ucsd.edu.

Brian E. Saelens, Email: brian.saelens@seattlechildrens.org.

REFERENCES

- Alliance for Biking and Walking. Bicycling and walking in the United States – 2010 benchmarking report. Washington, DC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Chang JJ, Eyler AA, Ainsworth BE, Kirtland K, Saelens BE, Sallis JF. Measuring the environment for friendliness toward physical activity: A comparison of the reliability of 3 questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:473–483. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Mokhtarian PL, Handy SL. The relationship between the built environment and nonwork travel: A case study of Northern California. Transport Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2009;43:548–559. [Google Scholar]

- De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Environmental correlates of physical activity in a sample of Belgian adults. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18:83–92. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J. Bicycling for transportation and health: The role of infrastructure. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30:S95–S110. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J, Carr T. Bicycle commuting and facilities in major U. S. cities: If you build them, commuters will use them. Transport Res Record. 2003;1828:116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Leerssen C, Chapman J, Contrino H. Strategies for Metropolitan Atlanta’s Regional Transportation and Air Quality (SMARTRAQ) Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Leary L, Cain K, Conway TL, Hess PM. The development of a walkability index: Application to the neighborhood quality of life study. Brit J Sports Med. 2010;30:601–611. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy SL, Boarnet MG, Ewing R, Killingsworth RE. How the built environment affects physical activity views from urban planning. American Journal of Prev Med. 2002;23:64–73. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek KJ, Barnes G, Thompson K. Analyzing the effect of bicycle facilities on commute mode share over time. J Urban Planning Develop. 2009;135:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Krizek KJ, Kevin J, Johnson PJ. Proximity to trails and retail: Effects on urban cycling and walking. J Am Planning Assoc. 2006;72:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz WE. Adult bicyclists in the United States: Characteristics and riding experience in 1996. Transport Res Record. 1998;1663:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AC, Allen D. If you build them, commuters will use them: Association between bicycle facilities and bicycle commuting. Transport Res Record. 1997;1578:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Cerin E, Leslie E, duToit L, Coffee N, Frank LD, Bauman AE, Hugo G, Saelens BE, et al. Neighborhood walkability and the walking behavior of Australian adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucher J, Buehler R, editors. City Cycling. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pucher J, Buehler R, Bassett D, Dannenberg A. Walking and cycling to health: recent evidence from city, state, and international comparisons. Am J Public Health. 2010a;100:391–414. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucher J, Dill J, Handy S. Infrastructure, programs, and policies to increase bicycling: An international review. Prev Med. 2010b;50(Supp1):S106–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C, Harris MA, Teschke K, Cripton PA, Winters M. The impact of transportation infrastructure on bicycling injuries and crashes: A review of the literature. Environ Health. 2009;8:47–66. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1552–1558. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Cain KL, Conway TL, Chapman JE, Slymen DJ, Kerr J. Neighborhood environmental and psychosocial correlates of adults' physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:637–646. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318237fe18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Johnson MF, Calfas KJ, Caparosa S, Nichols JF. Assessing perceived physical environmental variables that may influence physical activity. Res Quart Exerc Sport. 1997;68:345–351. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Conway TL, Slymen DJ, Cain KL, Chapman JE, Kerr J. Neighborhood built environment and income: Examining multiple health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, Leibhaber A, Ezeamama A. Perceived safety of area of residence and exercise: A pan-European study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Transportation. The national walking and bicycling study: 15-year status report. Washington DC: U. S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Belle G. Statistical Rules of Thumb. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck D, Cardon G, Deforche B, Sallis JF, Owen N, De Bourdeadhuij I. Neighborhood SES and walkability are related to physical activity behavior in Belgian adults. Prev Med. 2010;50:S74–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernez-Moudon A, Lee C, Cheadle AD, Coolier CW, Johnson D, Schmid TL, Weather RD. Cycling and built environment, a US perspective. Transport Res Part D: Transport Environ. 2005;10:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wardman M, Tight M, Page M. Factors influencing the propensity to cycle to work. Transport Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2007;41:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Shannon T, Bulsara M, Pikora T, McCormack G, Giles-Corti B. The anatomy of the safe and social suburb: An exploratory study of the built environment, social capital and residents’ perceptions of safety. Health Place. 2007;14:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]