Abstract

Objective

A consensus meeting of representatives of 16 Latin American and Caribbean countries and the REAL-PANLAR group met in the city of Bogota to provide recommendations for improving quality of care of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Latin America, defining a minimum standards of care and the concept of center of excellence in RA.

Methods

Twenty-two rheumatologists from 16 Latin American countries with a special interest in quality of care in RA participated in the consensus meeting. Two RA Colombian patients and 2 health care excellence advisors were also invited to the meeting. A RAND-modified Delphi procedure of 5 steps was applied to define categories of centers of excellence. During a 1-day meeting, working groups were created in order to discuss and validate the minimum quality-of-care standards for the 3 proposed types of centers of excellence in RA. Positive votes from at least 60% of the attending leaders were required for the approval of each standard.

Results

Twenty-two opinion leaders from the PANLAR countries and the REAL-PANLAR group participated in the discussion and definition of the standards. One hundred percent of the participants agreed with setting up centers of excellence in RA throughout Latin America. Three types of centers of excellence and its criteria were defined, according to indicators of structure, processes, and outcomes: standard, optimal, and model. The standard level should have basic structure and process indicators, the intermediate or optimal level should accomplish more structure and process indicators, and model level should also fulfill outcome indicators and patient experience.

Conclusions

This is the first Latin American effort to standardize and harmonize the treatment provided to RA patients and to establish centers of excellence that would offer to RA patients acceptable clinical results and high levels of safety.

Key Words: rheumatoid arthritis, Latin America, quality of care, centers of excellence

The mission of PANLAR (Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology) is 2-fold: (1) to stimulate and promote the study and research of rheumatic diseases for the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of patients with rheumatic conditions in the American continent and (2) to stimulate the continuing development of the specialty of rheumatology. PANLAR is committed to encourage and facilitate patient access to care as it affects the ability of rheumatic disease patients to obtain affordable, high-quality, and specialized health care.

The national health care systems within the Latin America (LA) and Caribbean area are heterogeneous in their organizational structure and complex in their operational configuration and the principles guiding the public and private sector roles in the provision of health care services. Latin American and Caribbean countries exhibit wide variations regarding their main health care systems objectives and operation. Chronic illnesses, which greatly impact health and quality of life, are actually 1 of their priorities despite requiring efforts to manage the burden of infectious diseases, providing care for the reproductive-age female population, childhood pathology, and violence-related injuries, among others.1

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have substantial unmet medical needs. The World Health Organization recommends at least 1 rheumatologist per 100,000 people, that is, an estimated need of 6000 specialists in LA. Currently excluding the United States and Canada, the 19 LA and Caribbean Rheumatology National Societies have a workforce of around 3900 specialists to serve 588 million inhabitants. Not all rheumatologists are active, nor are they accredited according to country requirements.2

Although this number could be higher because some active practicing rheumatologists are not affiliated to their local societies, therefore, the actual number of specialists cannot be determined accurately. In addition to the shortage of rheumatologists in Latin American and Caribbean countries, the regional distribution on supply of specialists is mainly in metropolitan areas, whereas other areas have a low density of specialists, such as in rural areas and small towns, resulting in several underserved areas. These factors not only constitute barriers to patient access to specialized health care, but also contribute to a suboptimal quality of care provided, poor diagnosis, and treatment of RA in a large proportion of affected individuals.3,4

However this is not the only problem that RA patients face. Most patients in the region have limited access to medicines, rehabilitation programs, and orthopedic interventions, all of which are highly recommended for optimal disease management. Moreover, they do not have substantial education programs, which are necessary to empower them and their families in their daily management and adjustment to their illnesses, because drug therapy alone does not substantially improve quality of life.3,4 The data also reveal the importance of considering early diagnosis and adequate treatment of RA as a public health priority in Latin American and Caribbean countries, because early treatment of RA has shown to effectively reduce disability in the long run.3,4

Accurate measures known as quality indicators (QIs) are needed to assess quality of care. Quality indicators are usually more specific as compared with treatment recommendation guidelines, because they precisely describe who must do what, to whom, and exactly when.5 In 2007, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) submitted a set of minimum QIs for RA patient care; patient adherence to these standards seems possible. Introduction of these QIs presents clinicians with an enormous opportunity to clearly understand the minimum standards expected in the profession.6 An essential goal of QIs is establishing minimum standards of care that should be delivered to patients as a means to evaluate care across patients and provider groups and stimulate quality improvement efforts that ultimately lead to better patient care and outcomes.6

The involvement of national scientific specialty organizations is an important way of delivering the message that implementing these measures is necessary for patients with RA. Eventually, it may be feasible to move beyond the specification of minimal care and reach a consensus regarding good and excellent care for our patients. There is a great potential to reduce the large and growing burden of RA across the PANLAR member societies through evidence-based interventions and harmonization of the standards of care. The REAL (Red de Excelencia en Artritis para la América Latina) project evolved as a strategic need to implement Centers of Excellence (CoEs) in RA throughout the LA and Caribbean region to help ensure affordable, high-quality, and specialized health care for these patients, improving their quality of life and managing their health care costs. Taking into account the difficulties posed by diverse health system organizations across countries and lack of resources, the REAL main goals are as follows:

To promote assessment of standards of care for RA in alignment with PANLAR clinical guidelines and the Treat to Target (T2T) strategy7

To accomplish the need to measure and document disease activity, disability, comorbidities, quality of life, and adherence to treatment by RA patients

To establish harmonized minimum standards of care for RA patients

To inform doctors and other allied health professionals about all aspects of RA

To educate patients and their family members about the facts of RA in order to help them to cope with the disease and collaborate, improving adherence to treatment and rehabilitation programs

To improve patient accessibility to arthritis centers and implement continuous health care quality programs

To establish and foster Latin American and Caribbean regional registries and databases

To form a strategic alliance with Latin American and Caribbean governments and nongovernmental organizations in order to implement the T2T strategy and CoEs in RA throughout the LA and Caribbean region

To raise awareness about the need for CoEs in RA among policy makers, private and public health payers, and insurers in the region

METHODS

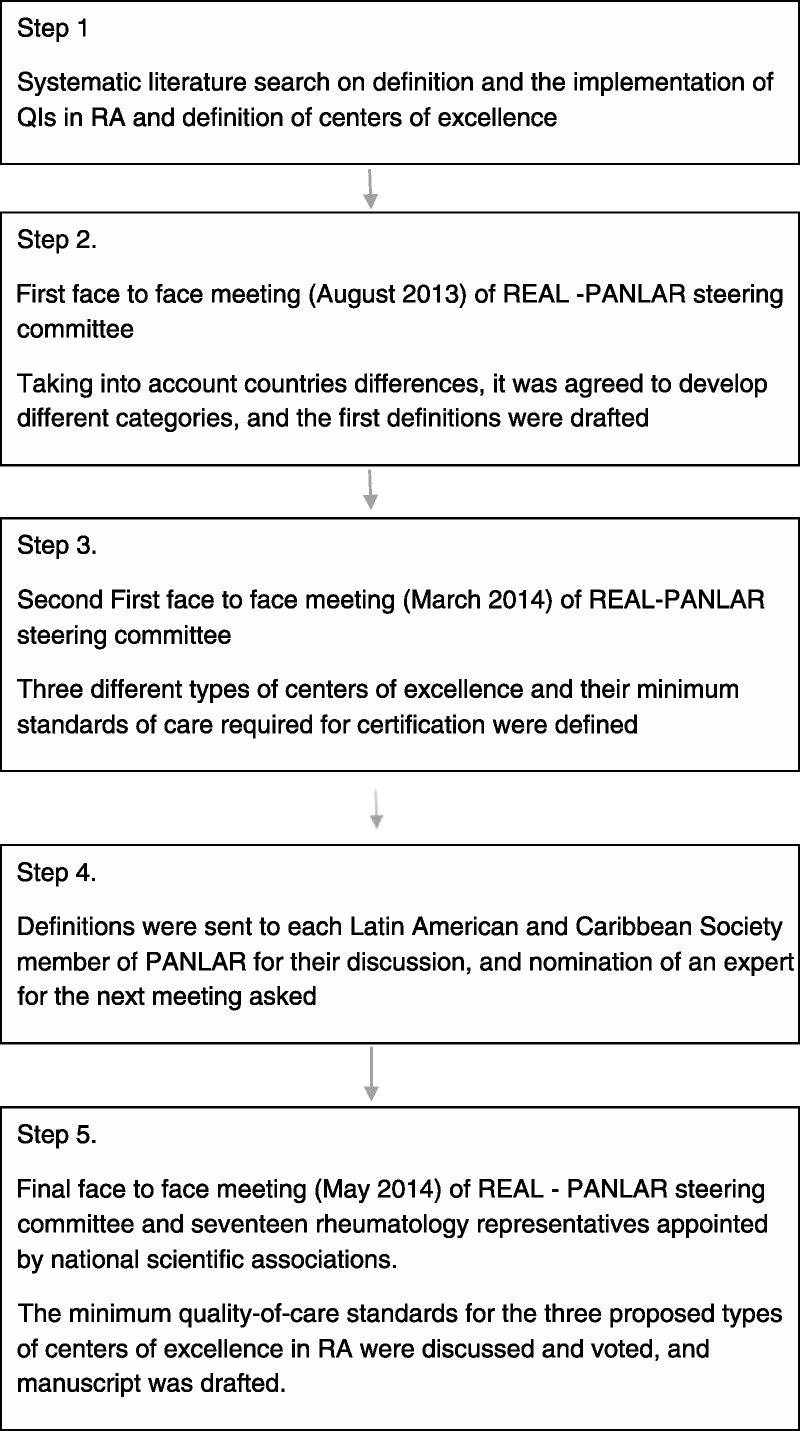

The category definitions of health care CoEs were established using the Modified Delphi-RAND 5-step method8,9 (Figure).

FIGURE.

Flowchart describing the procedures within each step in the consensus.

Step 1

Systematic search of the literature contained in MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, SciELO, and LILACS electronic databases, focusing on publications about the definition and the implementation of QIs in RA and the definition of CoEs. The documents are identified as references.5,6,10–20

Step 2

During the first meeting, held on the 30th and 31st of August 2013, a panel composed of Latin American experts in rheumatology defined the concept of CoE in arthritis care. A CoE in RA is a health care model coordinated by a rheumatologist where RA patients are managed in a comprehensive and systematic way in order to attain the best clinical and safety outcomes, improve administration and disease management indicators, and, ultimately, gather all kinds of data to generate both research and regional and national policies in relation to this condition.12

As mentioned previously, the national health care systems across the Latin American and Caribbean countries are heterogeneous in their organizational structure and complex in their operational configuration, and because of considerable differences among health care models, the CoEs in RA may be different in nature:

large public hospital centers offering rheumatology services

private centers or clinics that also provide rheumatology services

outpatient centers specializing in rheumatology

rheumatologist alone or in teams of rheumatologists

A decision was reached to define the quality standards for the different categories of CoEs in RA according to the review of the available literature.

Step 3

During the second meeting of experts held in Punta del Este (Uruguay), on March 20, 2014, the first definition of quality standards for the different types of CoEs was created, taking into account the following characteristics:

Step 4

The definition of the 3 different types of CoEs and the minimum standards required for their certification were sent for its review and analysis to the presidents of the national rheumatology scientific associations from the LA and Caribbean countries affiliated to PANLAR attending the next panel to discuss and produce the final recommendations. Each proposed category is associated with the following21:

-

structure indicators

a. medical and other health care providers

b. space for exclusive use

c. resources

-

process indicators

a. joint counts and clinimetric indexes (Disease Activity Score 28, Clinical Disease Activity Index, American College of Rheumatology 20 and others)

b. functionality indexes such as Health Assessment Questionnaire, among others

-

outcome indicators

Step 5

The panel was composed of 6 members of the REAL-PANLAR steering committee and 17 rheumatology representatives appointed by the national scientific associations from each country. They all met on May 17, 2014, in Bogota, Colombia; the meeting also was attended by 2 representatives of the Colombian Association of RA Patients and 2 health care excellence advisors who provided methodological support.22 After setting out the project and its justification, the opinion leaders were assigned to 4 working groups to discuss and validate the minimum quality-of-care standards for the 3 proposed types of CoEs in RA and for the process of accreditation of the centers, and their consensus was presented to the panel by a spokesman of each group and submitted for a final vote during the plenary session. Positive votes from at least 60% of the attending leaders were required for the approval of each standard. Lastly, the requirements for the definitions of the patient management and follow-up guides were discussed.

RESULTS

Sixteen opinion leaders from the PANLAR member countries and the members of the REAL-PANLAR steering committee participated in the discussion and definition of the minimum quality standards. Three types of CoEs were defined based on structure, process, and outcome indicators: STANDARD, OPTIMAL, and MODEL. The approved standards for the OPTIMAL CoE are implicit in the STANDARD 1, and the latter, in the MODEL 1; in other words the standard level should have basic structure and process indicators, the intermediate or optimal level should accomplish more structure and process indicators, and model level should also fulfill outcome and patient experience indicators.

Initially, some questions were raised about general needs, which the panel answered in the following manner: 100% of the participants agreed with setting up CoEs in RA throughout LA, and 95% of the participants agreed on the need to define levels/categories of excellence.

The detailed results of the approval of different quality standard requirements for each CoE model are listed in the Table 1. We note that all the criteria required in the lower levels of excellence must be met by the higher levels (ie, the criteria for the standard centers must be met by the optimal and model centers; criteria for the optimal centers must be met by the model centers).

TABLE 1.

Results of the Approval of Different Quality Standard Requirements for Each Center of Excellence (COE) Model

Patient Management and Follow-up Guidelines

The steering committee identified important amendments to be incorporated in the proposal. It unanimously considered that the follow-up should take place according to the following 6 characteristics:

clinimetrics

decision-making factors based on the results of the clinimetrics

opportunities to access treatment or follow-up

patient education

clinical care guidelines

evaluation system

The contents described in the document were accepted. The working groups considered it important to define that comprehensive and systematic care is part of the accreditation philosophy, and therefore, all components must be taken into account. No consensus was reached regarding the scoring value of each variable, but upon individual analysis of the criteria, priorities were established in the following order: clinimetrics, opportunity and access, decision making, clinical guidelines, and patient education.

The working groups also considered it necessary to identify the content of each criterion, but the meeting did not provide them with enough time to draft the fine details. It was established that, in order to maintain the comprehensive nature of care, all criteria must be met with a minimum score of 80% for each of the criteria. In addition and regardless of institutional category, all CoEs should meet the same standards, and according to the philosophy of the accreditation system, the concepts of continuous improvement and patient-centered management must be included.

Next Steps

The working group has planned the next course of action that we are summarizing as next steps:

Generate and provide a precise definition of each 1 of the variables and characteristics included in the project.

Identify and contract a professional and experienced third party to carry on with accreditation and certification according to the working party definitions.

Invite all centers in the associated countries to apply for the accreditation and certification process.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of establishing CoEs in rheumatology is to facilitate access to better quality treatment, achieve disease remission, improve their quality of life, and reduce long-term disability risks to RA patients.

This is the first effort by Latin American and Caribbean countries to harmonize the standard of care for RA patients and to establish CoEs that, according to PANLAR’s mission and their basic concept, offer patients to optimize clinical results and ensure high levels of safety. These should be comparable to the best reference points, highly competitive market costs, and minimal predetermined volumes and frequencies of care.

We are not able yet to analyze the impact of this project. As applications will be voluntary, we do not have a precise idea of the number of centers that would apply. We expect that several centers will apply for each category in the big Latin American countries, and we are sure that this would be a gradual process with more centers applying as more centers are accredited.

Some might be surprised by the high level of agreement we achieved within this consensus. We think that that was due to the fact that all the requirements for quality of care defined are evidence based, and even within the diversity of Latin American and Caribbean countries, most of the rheumatologists agree with them. We defined 3 different categories in order to allow almost every rheumatologist in our countries to be able to apply to at least 1 of them, provided that he/she can comply with minimum standards of care.

It might be that the rheumatologists selected being experts, even though coming from different countries, are very much alike among them, and this process might have a group bias, not representing the feelings of the majority of the rheumatologists from LA and the Caribbean. We considered performing a large survey, but we thought that a large survey would have been very difficult, and we rather opted for a representative approach, asking the PANLAR members societies to select a representative that was included in the consensus. We expect each society will support their representative and thereby promoting the general acceptance of the guidelines by the rheumatologist community.

We acknowledge that an important problem to attain this goal is the limited access to medication and rehabilitation depending on patient’s health coverage or insurance. However, this should not be an obstacle for a patient to attend a CoE in RA or for rheumatologists to improve their clinical rheumatology practice. Therefore, this panel of experts generates a position paper, supported by the scientific associations represented by their medical leaders that can come into force in LA through the implementation of these CoEs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Paulo Vega, MD, and Annette Pérez, MD, as Abbvie’s unrestricted educational grant managers, which made the project’s development possible; Ciro Valderrama and María Mercedes Rueda, as RA representative patients; Sergio Luengas, MD, and Luisa Pombo, MD, of the O.E.S. (Organizacion para la Excelencia en Salud–Excellence in Health Organization), experts in health quality and accreditation who were the methodological advisors of the meeting; and Drs Analhi Palomino and Laura Villarreal, from BIOMAB, Rheumatoid Arthritis Center, Bogota, Colombia, who were the logistic coordinators of the meeting.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barreto SM, Miranda JJ, Figueroa JP, et al. Epidemiology in Latin America and the Caribbean: current situation and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2012; 41: 557– 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al Maini M, Adelowo F, Al Saleh J, et al. The global challenges and opportunities in the practice of rheumatology: white paper by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases [published online ahead of print December 14, 2014]. Clin Rheumatol. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latin American Rheumatology Associations of the Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) and the Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio de Artritis Reumatoide (GLADAR). First Latin American Position Paper on the Pharmacological Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology. 2006; 45 ( suppl 2): ii7– ii22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Massardo L, Suárez-Almazor ME, Cardiel MH, et al. Management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America. A consensus position paper from Pan-American League of Associations of Rheumatology and Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio de Artritis Reumatoide. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009; 15: 203– 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Hulst LT, Fransen J, den Broeder AA, et al. Development of quality indicators for monitoring the disease course in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009; 68: 1805– 1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kahn KL, Maclean CH, Wong AL, et al. Assessment of American College of Rheumatology quality criteria for rheumatoid arthritis in a pre-quality criteria patient cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007; 57: 707– 715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69: 631– 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martínez-Sahuquillo A, Echevarría MC. Métodos de consenso. Uso adecuado de la evidencia en la toma de decisiones. “Método RAND/UCLA”. Rehabilitación (Madr). 2001; 35: 388– 392. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carreño M. El método Delphi: cuando dos cabezas piensan más que una en el desarrollo de guías de práctica clínica. Rev Colombiana Psiquiatr. 2009; 38: 185– 193. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Standards of Care for Osteoarthritis (OA) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). The British League Against Rheumatism. Booklet. Eagle Street, London: The British League Against Rheumatism; June 2012.

- 11. Petersson IF, Strombeck B, Andersen L, et al. Development of healthcare quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis in Europe: the eumusc.net project. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; 73: 906– 908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castaño Yepes RA. Centros de excelencia: calidad, eficiencia y competitividad para la exportación de servicios. Rev Salud. 2006: 8– 17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centros de Excelencia. Editorial del Centro de Gestión Hospitalaria. Rev Salud. 2006: 2– 3 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centros de Excelencia y significancia estadística. Editorial del Centro de Gestión Hospitalaria. Rev Salud. 2009: 2– 3 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cardiel MH. Estrategia “Treat to Target” en la artritis reumatoide: beneficios reales. Reumatología Clínica. 2013; 9: 101– 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alonso A, Vidal J, Tornero J. Assistance quality standards in rheumatology. Reumatol Clin. 2007; 3: 218– 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69: 964– 975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The International Society for Quality in Health Care. ISQua’s International Accreditation Standards for Healthcare External Evaluation Organisations. 3rd ed Dublin 2, Ireland: The International Society for Quality in Health Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams CA, Mosley-Williams AD, Overhage JM. Arthritis quality indicators for the Veterans Administration: implications for electronic data collection, storage format, quality assessment, and clinical decision support. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007; 11: 806– 810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adhikesavan LG, Newman ED, Diehl MP, et al. American College of Rheumatology quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis: benchmarking, variability, and opportunities to improve quality of care using the electronic health record. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 59: 1705– 1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saag KG, Yazdany J, Alexander C, et al. American College of Rheumatology Quality Measurement White Paper Development Workgroup. Defining quality of care in rheumatology: the American College of Rheumatology White Paper on Quality Measurement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011; 63: 2– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bingham CO, 3rd, Alten R, de Wit MP. The importance of patient participation in measuring rheumatoid arthritis flares. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012; 71: 1107– 1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]