In their 2011 article in Health Services Research, Monheit et al. (2011) use a conventional and seemingly unobjectionable difference-in-difference model to show that state-level reforms designed to extend access to parental insurance were associated with significant increases in the holding of dependent insurance among young adults. In Table 2 of my December 2014 paper in HSR, I was able to closely replicate their finding on “dependent” coverage (Burgdorf 2014). However, I also applied another innovation used by Monheit and colleagues (hereafter, the “Monheit team”) in their later work: the separation of dependent coverage into parental and spousal subcategories. This exercise made clear that their original finding of an increase in “dependent” coverage was secretly hiding an implausible increase in spousal coverage. Obviously spousal coverage did not increase, suggesting a problem with their model—a model that appears to be completely reasonable on its face.

Let me be clear, I, in no way, am making the claim that the policy effect did not work or that the policy effect is zero. I am merely saying that a model used to support such a conclusion does not provide adequate evidence of a true policy effect if it is driven by spousal insurance rather than parental insurance. Indeed, my reexamination of results produced by Levine, McKnight, and Heep (2011)—also presented in Burgdorf (2014)—suggested significant increases in parental coverage among certain subsets of eligibles. Furthermore, and as pointed out by myself (Burgdorf 2014) and by the Monheit team in their letter, work by Depew (2013, 2015) also suggests that the reforms did have a positive effect on parental coverage. Depew's work has many important advantages over other papers in the literature, including the use of panel data, the use of spousal coverage as an outcome, and the fact that eligibility is assumed on the basis of age rather than endogenous choice variables such as marital status or living with one's parents. However, the strengths and findings of Depew's study do not automatically transfer to other studies with similar results, let alone to papers using different dependent variables. Depew's findings do not validate the original Monheit et al. model, nor do they validate that model's findings as they were originally presented. Empirical researchers should never be satisfied reaching the “right” answer with the wrong model, let alone with the wrong outcome variable.

While working on my paper, I contacted the Monheit team and was graciously given the original code for their work in the true spirit of open science. In looking closely at their code, it was evident that their measure of dependent coverage did not separate out parental and spousal subcategories. In implementing this simple change, a change that the Monheit team implement themselves in later work, my replication of their model generated the clearly implausible result (as the policy was not designed to influence spousal insurance). I looked at the raw data to examine this and found that spousal coverage did not increase generally or in treatment states. So, in no way do I conclude from the outcome of that model, nor should anyone else, that the policy reforms being evaluated here increased the holding of spousal coverage; however, I do maintain that this is what their model shows, and I further argue that this “finding” suggests a serious problem with the model itself. In their letter in response to my paper, the authors demonstrate limited awareness that the estimated increase in spousal coverage is actually the troubling feature of their model, suggesting that my work argues that “the increase in dependent coverage of young adults through the state reforms was driven by enrollment in spousal dependent coverage.” This is not my argument, and it represents a misinterpretation of my conclusion, as I state above.

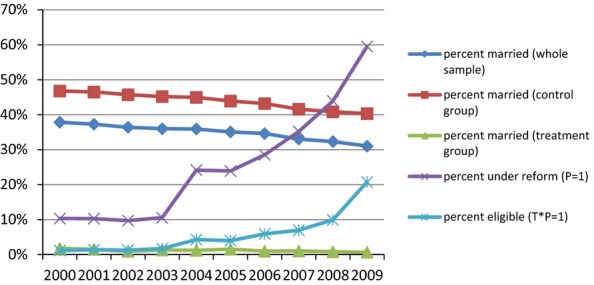

If one assumes that the reforms did have an effect on parental coverage, the question becomes: why is the Monheit team's model unable to show it, and why, instead, does it show an increase in spousal coverage? The answer to this question could have profound implications not just for observers interested in the reforms themselves but also for practitioners of difference-in-difference methods as well as for users of the Current Population Survey (CPS). Because the CPS serves as the main basis for insurance coverage estimates in the United States, proper estimation of the effect size within the CPS is still an important task, as is estimation of the effects within different subpopulations. Though I suggest possible reasons such as secular trends in marital rates (shown in Figure1) or living with parents, and/or the endogeneity of treatment assignment, the Monheit team is correct to note that I am unable to conclusively explain their model's odd results. In this, I am joined by the Monheit team itself. To their credit, their letter does suggest one explanation, that the CPS's designation of parental and spousal coverage is untrustworthy. If so, that would constitute “news” and would be an important result of this discussion, even as it calls into question other published results by their team and other teams that have made this increasingly common distinction (e.g., Antwi, Moriya, and Simon 2012; Cantor et al. 2012; Lloyd et al. 2014). However, to produce an erroneous estimate of an increase in spousal coverage, the error would have to be so systematic that it would seem unlikely. For individuals with dependent coverage, the CPS records the line number of the insurance “holder” in a separate variable, which is in almost all cases either a spouse or a parent. Is it really plausible that so many cases of a parental holder's line number were accidentally replaced by a spousal line number that a standard difference-in-differences model would erroneously detect increases in spousal dependent coverage, but not parental dependent coverage? Note that even if we were to defer to the results on dependent coverage generally, Table 2 of my paper also shows a positive effect on employer-sponsored dependent coverage even within the context of a falsification test that reassigned states’ FIPS codes upward (Burgdorf 2014).

Figure 1.

Declining Proportion of Married Individuals among Treatment Population Relative to Control Population, and Increasing Probability of Reform Eligibility (Ages 22 through 29)

Though in their letter the Monheit team describes additional checks on shifting subpopulations defined by endogenous choice variables (namely, marital status and living with parents), and they continue to report significant effects on dependent coverage, they conspicuously decline to differentiate between spousal and parental coverage. Had they differentiated between spousal and parental coverage in the work leading up to their original paper, they likely would have found, as I did, that their results were driven by the spousal side, and they would be reluctant to obscure the issue for readers by only reporting results for dependent coverage generally. Would any researchers be satisfied by a model that showed, for example, that a policy to increase Social Security payments was associated with significant increases in overall income and wage income, but not with Social Security income? Would it help that model's case if other researchers using different models and datasets did demonstrate an increase in Social Security income specifically? An implausible result such as this would ideally incite thoughtful reconsideration of the model itself by its own creators, rather than distracting attempts to reframe the results as belonging to someone else. Perhaps, other researchers familiar with the CPS, difference-in-difference model limitations, or the state-level parental coverage expansions will be able to offer their insights.

References

- Antwi YA, Moriya AS. Simon K. Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. NBER Working Paper 18200. [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf JR. Young Adult Dependent Coverage: Were the State Reforms Effective? Health Services Research. 2014;49(S2):2104–28. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor JC, Monheit AC, DeLia D. Lloyd K. Early Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage of Young Adults. Health Services Research. 2012;47(5):1773–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depew B. Public Policy and Its Impact on the Labor Market. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Depew B. The Effect of State Dependent Mandate Laws on the Labor Supply Decisions of Young Adults. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;39:123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine PB, McKnight R. Heep S. How Effective are Public Policies to Increase Health Insurance Coverage among Young Adults? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2011;3(February):129–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K, DeLia D, Cantor J. Monheit AC. Expanded Young Adult Dependent Coverage under the Affordable Care Act and Its Implications for Risk Pooling. State Health Access Reform Evaluation. 2014 [accessed April 14, 2015]. Available at http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2014/rwjf412478. [Google Scholar]

- Monheit AC, Cantor JC, DeLia D. Belloff D. How Have State Policies to Expand Dependent Coverage Affected the Health Insurance Status of Young Adults? Health Services Research. 2011;46(1, Part II (February)):251–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]