Abstract

When people have an interest in keeping other people down, in or away, stigma is a resource that allows them to obtain ends they desire. We call this resource “stigma power” and use the term to refer to instances in which stigma processes achieve the aims of stigmatizers with respect to the exploitation, control or exclusion of others. We draw on Bourdieu (1987; 1990) who notes that power is often most effectively deployed when it is hidden or “misrecognized.” To explore the utility of the stigma power concept we examine ways in which the goals of stigmatizers are achieved but hidden in the stigma coping efforts of people with mental illnesses. We developed new self-report measures and administered them to a sample of individuals who have experienced mental illness to test whether results are consistent with the possibility that, in response to negative societal conceptions, the attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of people with psychosis lead them to be concerned with staying in, propelled to stay away and induced to feel downwardly placed –precisely the outcomes stigmatizers might desire. Our introduction of the stigma power concept carries the possibility of seeing stigmatizing circumstances in a new light.

When people have an interest in keeping other people down, in or away, stigma is a resource that allows them to obtain ends they desire. We call this resource “stigma power” and use the term to refer to instances in which stigma processes achieve the aims of stigmatizers with respect to the exploitation, management, control or exclusion of others. Drawing on Bourdieu’s (1987;1990) concepts of symbolic power and misrecognition, our central thesis is that many stigma processes serve the interests of stigmatizers in subtle ways that are difficult to recognize in the absence of conceptual tools that bring them to light. Indeed, when we scan extant literature on stigma, prejudice and discrimination, we note (see below) that in many instances the processes described are ones that are hidden from a casual observer’s view. The concept of stigma power brings to the forefront the idea that these hidden, misrecognized processes serve the interests of stigmatizers and are part of a social system that gets them what they want. In keeping with this thesis, we explore one avenue through which stigma power is exercised in the area of mental illness. Specifically, we use the concept of stigma power as an additional lens through which to observe what had previously been conceptualized as stigma coping or stigma management efforts. We note that many of the things people with mental illnesses do to cope with stigma ultimately achieve the goals of stigmatizers by inducing strong efforts to stay “in,” “down” or “away.” When this happens, persistent, patterned and in this instance hierarchical social relationships between people with mental illnesses and people without them are created and sustained. In what follows we 1) develop the concept of stigma power, 2) examine the literature on stigma-related mechanisms of discrimination from the vantage point of the stigma-power concept, 3) apply the concepts in the area of mental illnesses, and 4) examine whether empirical relationships between measures of mental-illness stigma are consistent with a stigma-power conceptualization.

The Stigma-Power Concept

At its essence the stigma-power concept proposes that stigmatizers have strong motivations to keep people down, in or away and that they best achieve these aims through stigma processes that are indirect, broadly effective, and hidden in taken-for-granted cultural circumstances. We draw on concepts from Phelan, Link and Dovidio (2008) and Bourdieu (1987) to conceptualize the hidden, misrecognized cultural circumstances that make stigma processes effective.

The Motivation to Stigmatize

Phelan, Link and Dovidio (2008) identify three generic ends that people can attain through stigma. In the first, exploitation and domination or “keeping people down,” wealth, power, and high social status can be attained when one group dominates or exploits another (Phelan et al., 2008). Classic examples are the racial stigmatization of African Americans in the era of slavery, the Europeans’ colonization of countries around the globe, and U.S. whites’ expropriation of the lands of American Indians (Feagin 2009; Feagin and Bennefield, This Issue). In the second, enforcement of social norms or “keeping people in,” people construct written and unwritten rules regulating everything from how soldiers should fight wars to how people should sip tea. Stigma imparts a stiff cost that can both keep the norm violator in and serve as a reminder to others that they should remain in as well (Erikson, 1966). In the third, avoidance of disease or “keeping people away,” deviations from the organism’s normal (healthy) appearance such as asymmetry, marks, lesions and discoloration; coughing, sneezing and excretion of fluids; and behavioral anomalies due to damage to muscle-control systems could signal a danger of infection and induce people to want to stay away (Kurzban & Leary, 2001, p. 197). The evolutionary advantage of avoiding disease might have led to a more general distaste for deviations from any local standard for the way humans are supposed to look or carry themselves leading to a strong desire to stay away from people who deviate with respect to a broad band of physical or behavioral characteristics.

The key point is that whether it is to keep people down, in, or away, there are motives or interests lying beneath the exercise of stigma. With clear motivations identified, we might expect people to use power to achieve the ends they desire, and it is our claim that stigma is frequently the power mechanism of choice.

Stigma Power, Symbolic Power and Misrecognition

For Bourdieu (1987) symbolic power is the capacity to impose on others a legitimatized vision of the social world and the cleavages within that world. His theorizing about symbolic power has three implications for our understanding stigma. First, in Bourdieu’s theorizing, cultural distinctions of value and worth are critically important mechanisms through which power is exercised. As stigma represents a statement about value and worth made by stigmatizers about those they stigmatize, stigma is, in Bourdieu’s terms, a form of symbolic power. Second, according to Bourdieu people who are disadvantaged by the exercise of symbolic power are often influenced, sometimes without realizing it, to accept cultural assessments of their value and rightful (lower) place in the social order. With respect to stigma, this is evident in the idea of “internalized” or “self” stigma (Corrigan & Watson 2002). Finally, the exercise of symbolic power is often buried in taken-for-granted aspects of culture and thereby hidden or “misrecognized” by both the people causing the harm and by those being harmed (Bourdieu 1990). Misrecognition serves the interests of the powerful because it allows their interests to be achieved surreptitiously. We adopt Bourdieu’s theorizing in the development of the stigma-power concept and expect that when we turn to the literature on stigma, prejudice and discrimination, we will see evidence that the interests of stigmatizers are often effectively achieved in hidden and indirect ways.

Mechanisms of Discrimination from the Vantage Point of the Stigma-Power Concept

A massive and very flexible repertoire of approaches is available to exercise stigma power. There are so many ways to put people down, slight them, exclude them, avoid them, reject and discriminate against them that when motivation and power are in place, stigma processes offer a handy toolkit to achieve desired ends (Hatzenbeuhler et al. 2013). In previous work, we identified several generic processes through which discrimination occurs – direct person-to-person discrimination, interactional discrimination, structural discrimination, and discrimination that operates through the individual (Link and Phelan 2001).

Direct Person-to-Person Discrimination, the most obvious and most widely recognized form of discrimination, occurs when one person discriminates against another based on openly expressed prejudicial attitudes or stereotypes (Allport, 1954). But blatant person-to-person discrimination brings significant problems for the stigmatizer. Setting people apart in a lower status using only direct forms of discrimination would exhaust the capacity of the stigmatizer to always be present, always be ready and always have the resources at hand to discriminate effectively. Further, there are often strong norms or laws against discrimination and often people know it is not socially acceptable to stigmatize others. Finally, the interests of the stigmatizer are apparent (or can be made to be so) in direct discrimination, and when interests are apparent, they can be challenged. Things work more smoothly for stigmatizers if their interests are misrecognized by others and themselves such that they are either not observed at all or judged to be just the natural order of things (Bourdieu, 1990). In sum, person-to-person discrimination is a clumsy tool because it is too difficult, too embarrassing or too easily recognized to be used broadly and effectively. As a consequence of the difficulties involved in direct person-to-person discrimination, other means to achieve desired ends are required.

Structural Discrimination

Many of the articles in this special issue join a growing body of research that shows that structural discrimination disadvantages stigmatized groups cumulatively over time via social policy, laws, institutional practices, or negative attitudinal social contexts (Hatzenbuehler et al, This Issue, Lukachko et al., This Issue). Such structural-level factors can serve to keep people down, in or away, and while they are often extremely explicit and directly discriminatory, they nevertheless exempt individual stigmatizers from the burden or embarrassment of directly exercising discrimination. From a stigma-power perspective an individual stigmatizer’s interests need not be expressed or even acknowledged as his/her aims are effectively achieved at the macro level.

Interactional Discrimination

In this form of discrimination people bring expectations or schemas that relate to characteristics that are made salient in an interaction. A person interacting with someone who carries a stigmatized status may behave differently, with hesitance, uncertainty, superiority or even excessive kindness. The person with the stigmatized status reacts, responding perhaps with less self-assurance or warmth, causing the interaction partner to dislike him/her. The end result is an emergent property of the interaction which if repeated over multiple circumstances results in the stigmatized person being excluded and assigned a lower social status (e.g. Sibicky and Dovidio 1986; Taylor, This Issue, Phelan et al., This Issue). Although strong inequalities emerge in these interactions, it is often true that neither participants nor casual observers would notice obvious acts of discrimination, thereby allowing stigma power to be exercised in ways that are misrecognized.

Discrimination Operating through the Stigmatized Person

A final mechanism focuses on stigmatized individuals themselves who in reacting to societal stereotypes are pushed to remain in, be kept away or be placed down. As a prominent example, consider theory and research relating to the concept of stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson, 1995). According to this theory, people know about the stereotypes that might be applied to them and experience these stereotypes as “threats” when they encounter situations in which they might be evaluated in accordance with the stereotype or confirm the stereotype through their behavior. The striking finding from this program of research is that people subjected to stereotype threat can be significantly disadvantaged in key domains such as test performance. In addition to stereotype threat, concepts and theories such as “stigma consciousness” (Pinel, 1999), “rejection sensitivity” (Downey et al., 2004, Pachankis and Hatenbuehler, This Issue), “concealment” and its psychological costs (Quinn and Chaudoir 2009), and “modified labeling theory” (Link et al 1989; 2008), all point to ways in which the existence of cultural stereotypes complicate and harm stigmatized groups even in the absence of direct person-to-person discrimination. Because these forms of stigmatization operate through stigmatized individuals’ knowledge of and potential acceptance of ambient stereotypes, one cannot pinpoint a specific perpetrator leaving the discrimination hidden and misrecognized.

Applying the Concept of Stigma Power to the Stigma of Mental Illnesses

If the concept of stigma power has utility, we should be able to locate specific instances in which the aims of stigmatizers are achieved covertly. To explore this possibility we turn to stigma as it pertains to mental illnesses, focusing first on the interests stigmatizers have with respect to keeping people with mental illnesses in, down or away, then turning to an analysis of how these interests might be achieved through social psychological processes operating within the stigmatized individual.

The Interest of Stigmatizers in Keeping People with Mental Illnesses In, Away, or Down

Based on a strong emphasis in sociological thinking about “residual rule breaking” (Scheff 1966) and the extension of that thinking through the sociology of emotions to “feeling rules” (Thoits 1985), we argue that the major reason for the stigmatization of people with mental illnesses is an attempt to keep people in. Initial reactions to symptoms are often common-sense attempts to alter rule-breaking behavior by, for example, strongly disapproving of strange beliefs expressed by people with psychosis, admonishing a person with depression to “snap out of it,” or passing favorite foods into the sight lines of a person with anorexia. At the same time, the bizarre behavior of psychosis; the weight loss, enervation, and anhedonia of depression; or the extreme underweight associated with anorexia could stimulate a desire for “disease avoidance” and a visceral inclination that keeps people away. Although there is little reason to suppose that mental illnesses are stigmatized so that those who suffer from them can be exploited or dominated for pecuniary gain, when efforts to keep people in fail as commonsense approaches to curbing symptoms are revealed to be ineffective, keeping people away can be substituted as a strategy to avoid non-normative behavior. And to the extent that keeping people away is more easily achieved when people are relatively powerless we might expect that keeping people down would also be prominent in the case of serious mental illnesses. Thus we expect a strong initial motivation to stigmatize mental illnesses resides in efforts to keep people in, but when symptomatic behaviors endure and efforts to keep people in fail, motivations to keep people down and away are also evident.

Keeping People with Mental Illnesses In, Away and Down

The question we address now is whether, as a stigma-power conceptualization might suggest, the interests of stigmatizers in keeping people in, away or down can be achieved covertly through social psychological processes operating through people with mental illnesses. Our point of departure is modified labeling theory (Link et al., 1989) a theory that specifies a threat to people with mental illnesses in general societal conceptions and then examines coping orientations people adopt to deal with that threat. Here we start with this theory but reexamine the processes it specifies through the lens of a stigma-power conceptualization.

Modified labeling theory asserts that, during socialization, people obtain mainly negative beliefs about mental illnesses and how other people will react to someone who has one. Then, for someone who develops and is labeled as having a mental illness, the beliefs one holds become personally applicable, potentially causing the individual to feel bad about having acquired a status that is negatively valued. Further, the individual may cope with this circumstance by avoiding or withdrawing from potentially threatening interactions or hiding a history of hospitalization. These coping actions can cut a person off from a broader set of social ties if, for example, one does not try for a job, ask for a date, or seek a supportive friendship. Finally, anticipating rejection can affect performance in social interactions if one is distracted by, or loses confidence because of, the worry that others might be rejecting (Link et al. 1989). This approach has been helpful in understanding why people with mental illnesses experience low self-esteem (Link et al 2001), constricted social networks (Link et al. 1989), diminished quality of life (Rosenfield 1997) and other social deficits. Here we examine modified labeling theory through a different lens by placing it within the conceptual framework of a stigma-power perspective. Specifically we ask whether the cascade of circumstances that follows from the generally negative societal evaluations identified by modified labeling theory achieve ends that stigmatizers desire – keeping people with mental illnesses in, or if that fails, down and away.

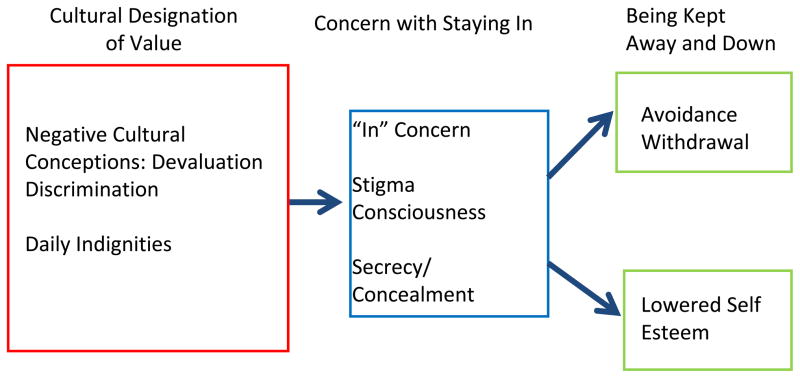

Figure 1 depicts a cascade of circumstances that follows from modified labeling theory but recasts the emphasis from a stigma coping frame of reference to a stigma power formulation. Specifically it presents domains relevant to 1) general cultural conceptions, 2) concern with staying in, 3) being kept away and 4) feeling down. We indicate the operational measures we use to capture elements of each domain in the boxes in Figure 1 and in parentheses in the text. As we consider each domain, we draw on theories of minority stress (Meyer 2003) to bring to light that any level of concern in each area is an added concern that people in a minority group experience that people in non-minority groups do not. Thus even a modest level of concern in any domain is more concern than someone who does not have the minority status in question would experience.

Figure 1.

The Stigma Power Process -- Concepts and Operationalizations

Cultural Assessment of Value

First, people with psychosis will be aware that having a mental illness and being hospitalized for that illness are associated with negative societal evaluations (Perceived Devaluation/Discrimination). Further, in keeping with this negative cultural evaluation, people with psychosis will report negative treatment associated with their status such as being taken less seriously, being treated unfairly, or being taken advantage of (Daily Indignities).

Concern with Staying “In”

Second, because of the negative cultural climate surrounding them, people with psychosis will often be concerned with staying “in” so as to avoid a connection with the negatively valued designation of mental illness. People will monitor social situations and express concern that even minor deviations from social norms might be viewed by others as signs of mental illness (“In” Concern). Further, people will wonder whether others are interacting with them in terms of their mental illness: “Are people treating me the way they are because I am a person who has a mental illness?” (Stigma Consciousness). Finally, people with psychosis may seek to be perceived and treated as someone who has stayed “in” by concealing a history of mental illness (Secrecy). These three domains – a prominent concern with staying within normative boundaries, a consciousness about how one is perceived by others, and a strategy of secrecy-- can all be conceptualized as concerns with staying “in.” To the extent that any of these are translated into effective action that keeps people in, the goal of those who would stigmatize is achieved.

Being Kept Away

Third, the negative cultural context induces an expectation of potential rejection or awkward interactions, and this concern might lead to avoidance of contact or withdrawal from potentially threatening interactions (Withdrawal). People might choose to limit contact to others who also have a mental illness or who know about and accept the person’s history of hospitalization. When withdrawal is effectively enacted, the stigmatizer’s goal of keeping people away is achieved.

Being Kept Down

Fourth, as a consequence of the negative cultural evaluation of mental illness, people who have such an illness may experience a downward placement, believing themselves to be a person of lower worth or value (Low Self-esteem). While this downward placement – keeping people down – is not an initial goal of those who stigmatize, such placement helps with respect to keeping people in or away. Downwardly placed people can be influenced or controlled with smaller incentives and are less likely to make or be able to demand broader inclusion.

Connections between Cultural Assessments of Value, Being Kept In, Kept Away and Kept Down. As Figure 1 shows, we expect general negative societal conceptions about mental illnesses to lead to a desire to stay “in” so as to avoid a strongly negative connection with a mental illness label. Then, because concerns about staying “in” underscore the salience of the negative designations, people are induced to withdraw from social contacts (kept away) and feel downwardly placed with respect to selfesteem (kept down).

The data that were available to us for examining the hypothesized relationships are cross-sectional and carry the well-known weaknesses associated with that design. Thus while the data cannot provide a definitive test of the model, they are useful for assessing its plausibility. There are two ways in which the data could lower our confidence in the hypothesized model. First, the results might show little evidence that people with mental illnesses are aware of negative cultural conceptions, are concerned with “staying in,” report wanting to stay away and feel downwardly placed. In such a circumstance, people would not endorse items measuring the constructs involved, and multiple-item measures would fail to cohere into internally consistent scales. Second, we might also find little evidence that the constructs are associated with one another in ways that are predicted by the conceptualization. If either of these two empirical possibilities emerges, our confidence in the conceptualization of stigma power will be diminished. On the other hand, if evidence emerges that is consistent with expectations, some support for the conceptualization will be garnered, suggesting that further testing of the ideas would be worthwhile.

Methods

Sample

The “Stigma and Psychosis” study recruited 65 male (72%) and female patients from four inpatient psychiatric hospitals in New York City (n=3) and New Jersey (n=1) between 2007 and 2009. To be included in the study, patients needed to 1) have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (N=26), schizophreniform (N=1), schizoaffective (N=11), delusional (N=1) or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (N=26), 2) be able to complete the interviews in English, and 3) have experienced fewer than six previous hospitalizations. The latter requirement was implemented in light of what Cohen and Cohen (1984) have described as “The Clinician’s Illusion” to facilitate the assessment of stigma amongst people whose experience was not overly affected by a chronic course of illness. Potentially eligible participants were identified by reviewing hospital charts of persons newly admitted to inpatient units and by accepting recommendations of staff in those units. As the concept of the Clinician’s Illusion would predict (Cohen and Cohen 1984) individuals with fewer than six hospitalizations were quite rare in settings where one would expect more chronic cases to build up. As a result we did not sample our participants from the larger pool of inpatients but rather sought to recruit all patients meeting inclusion criteria, with recruitment proceeding only after a patient’s main therapist confirmed that the patient was capable of giving informed consent. Once identified as eligible, very few patients refused participation. All interviews were completed in person in private rooms within the hospital by trained research interviewers. As a result missing data were rare and for items in multiple-item scales replaced with the mean for that item. The median age of participants was 25 (range 18–54), and most (88%) had never been married. Based on self-identification, 49% were African American, 22% Hispanic, 18% white and 11% other (mainly Asian). Forty-four percent completed some college or more.

Measures

We operationalized the constructs presented in Figure 1 using self-report multiple-item scales. The exact wording of each question in these scales, response options and frequencies are presented in online tables. Here we briefly introduce each construct and report example items and responses to those items in the results section.

Cultural Assessment of Value

We use a 12-item version of Link’s (1987) Perceived Devaluation–Discrimination Scale (alpha = .80) that asks whether respondents strongly agree (0), agree (1), disagree (2) or strongly disagree (3) with statements indicating that most people devalue or discriminate against people who have been in mental health treatment.

Daily Indignities (8 items, alpha = .85) were assessed by asking whether participants had experiences such as being taken advantage of, having one’s feeling hurt, or having people act uncomfortable very often (4), fairly often (3), sometimes (2), almost never (1) or never (0) during the past 3 months.

Concern with Staying In

We operationalized a concern with staying in using three multiple-item scales. The first is a six-item scale (alpha = .76) we developed and called Concern with Staying In. It draws on the concept of “rejection sensitivity” (Downey et al. 2004), which emphasizes how concerned someone would be to engage in an interaction that carries the potential for rejection. We provided respondents brief scenarios describing situations in which they might be perceived to be losing control or identified as having a mental illness and asked how concerned they would be (very unconcerned, 1; somewhat unconcerned, 2; somewhat concerned, 3; very concerned, 4) about other people’s reactions in the described situation.

The second draws on Pinel’s (1999) concept of Stigma Consciousness to assess individuals’ chronic awareness of their stigmatized status and their monitoring of situations to determine whether people are treating them in accordance with that status. We developed a five-item measure (alpha = .64) by asking respondents whether they “strongly disagree” (3), “disagree” (2), “agree” or (1) “strongly agree” (0) with statements indicating such a concern.

The third operationalizes Secrecy using a five-tem measure (alpha = .85) that asks how often in the past three months -- very often (4), fairly often (3), sometimes (2), almost never (1) or never (0) – respondents took action to conceal a history of psychiatric hospitalization.

Being Kept Away

We operationalized Being Kept Away using a five-item scale (alpha = .71) that captures the frequency of withdrawal, a concept that was originally introduced by Goffman (1963) and operationalized by Link et al. (1989) using a different set of items than the ones used here. The items assess whether people avoid interactions that may be rejecting or whether they feel more comfortable being with people who also have a mental illness.

Being Kept Down

Being kept down was measured using an eight-item version of Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (alpha = .81) that asks respondents whether they “strongly disagree” (3), “disagree” (2), “agree” (1) or “strongly agree” (0) with questions about whether the respondent feels they can do things as well as most people or have respect for themselves.

Results

Levels of Endorsement of Key Constructs

Cultural Assessments of Devaluation and Discrimination. Consistent with previous research (e.g. Link et al. 1989), study participants endorsed statements indicating that people with mental illnesses are devalued or discriminated against by most people. For example, 69% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “Most people would be reluctant to date someone who has been hospitalized for mental illness,” and 48% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “Most people believe that a person who has been hospitalized for mental illness is just as trustworthy as the average citizen.” Only two people (3%) in the sample failed to endorse any one of the 12 items, whereas 88% endorsed three or more.

With respect to daily indignities, three quarters of respondents reported at least one of the experiences in the three months prior to interview. For example, 45% reported being treated unfairly, 38% indicated that other people avoided them, and 23% said that others had used the fact of their hospitalization to gain an unfair advantage over them. More than half reported three or more (out of eight) daily indignities.

Concern with Staying In. Respondents report substantial levels of concern about staying within normative boundaries. For example, 66% report that they would be somewhat or very concerned that a friend would think they were losing control and showing signs of mental illness in a scenario in which they raised their voice in an argument. Ninety-one percent would be somewhat or very concerned that a potential employer would be biased against them if they reported a history of mental hospitalization on a pre-interview questionnaire. All respondents were at least somewhat concerned in at least one of the scenarios, and half were somewhat or very concerned in all of them.

Respondents also indicated a concern with staying in by reporting “stigma consciousness.” For example, 45% disagreed with the statement “my having a mental illness does not influence how people act with me” and 59% disagreed with the statement “most people do not judge someone on the basis of their having a mental illness.” Across the five items in the scale, 90% responded in a fashion reflecting stigma consciousness on at least one item.

Respondents also expressed concern with staying in by indicating a desire to conceal their history of hospitalization from others. In this regard, 46% reported that they kept their hospitalization for mental illness a secret at least sometimes or more in the three months before the interview, and 65% indicated that they were careful whom they told about their hospitalization. Overall, only 14% of respondents consistently (across all items) indicated that they had never concealed their history of hospitalization.

Being Kept Away. General negative cultural conceptions and concern about staying in can be sources of a desire to stay away. Consistent with this possibility, 28.5% of respondents indicated that during the past three months they had avoided “social situations involving people who have never been hospitalized for mental illness” and 78.5% indicated that they had felt “more at ease around people who have also had a mental illness.” Across the five items measuring withdrawal, fewer than one in ten (8%) reported no inclination to avoid and more than third (37.5%) endorsed three or more of the five items.

Being Kept Down. With respect to lowered self-esteem, most (82%) respondents reported low self esteem on at least one of the eight items. Forty-eight percent agreed with the statement that “At times I feel I am no good at all” whereas 19% disagreed with the statement that “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” Over all the items, 36% indicated low self esteem on at least 3 items. The mean of the scale in this sample is substantially lower (.6 of a standard deviation) than the mean in a sample of the general population (Sinclair et al. 2010).

Associations Among Domains According to a stigma-power conceptualization, two sets of associations should be evident in the empirical data. To begin, societal conceptions about whether most people devalue and discriminate against people with mental illnesses, together with daily indignities, are expected to lead to concerns with staying in. Then a concern with staying in reinforces the salience of negative evaluations and induces people to stay away or feel downwardly placed. Tables 1 and 2 present results that reflect on whether empirical findings are consistent with these expectations.

Table 1.

Regression Analyses Showing Effects of Perceived Devaluation Discrimination and Daily Indignities On Variables Assessing Concern with Staying In (N=64) 1

| Concern With Staying In | Stigma Consciousness | Secrecy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Perceived Devaluation - Discrimination | .234+ | --- | .196 | .380** | --- | .353** | .309* | --- | .271* |

| Daily Indignities | --- | .260* | .226+ | --- | .218+ | .157 | --- | .277* | .230+ |

| R-square | 23.1+ | 24.1* | 27.7* | 30.6** | 21.3* | 32.8** | 20.6+ | 18.6 | 25.4+ |

| R-square Increment Above Controls | 5.2* | 6.2* | 9.8* | 13.7** | 4.4+ | 15.9** | 9.1* | 7.1* | 13.8* |

P<.10;

P<.05;

P<.01

Standardized coefficients with associations adjusted for age, gender, education, race/ethnicity and psychiatric diagnosis

Table 2.

Regression Analyses Showing Effects of Devaluation Discrimination, Daily Indignities and Variables Assessing Concern with Staying In on Withdrawal and Self Esteem (N=64) a

| Withdrawal | Self Esteem | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Perceived Devaluation - Discrimination | .233* | .122 | −.272* | −.053 |

| Daily Indignities | .342* | .220* | −.061 | .078 |

| Concern with Staying In | --- | .108 | --- | −.194 |

| Stigma Consciousness | --- | −.140 | --- | −.395** |

| Secrecy | --- | .496 | --- | −.139 |

| R-square | 29.3** | 50.7*** | 23.1* | 40.7** |

| R-square Increment Above Controls | 19.1** | 21.4*** | 8.2+ | 17.6** |

P<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01

Standardized coefficients with associations adjusted for age, gender, education, race/ethnicity and psychiatric diagnosis

Table 1 shows that perceived devaluation and discrimination from most people and daily indignities are associated with measures of a) concern with staying within normative boundaries, b) stigma consciousness, and c) secrecy. There are three equations for each of these dependent variables: the first enters perceived devaluation/discrimination without daily indignities, the second daily indignities without perceived devaluation/discrimination and the third enters both devaluation/discrimination and daily indignities. This allows us to examine the effects of the two key explanatory variables separately and in concert. In all instances we report standardized regression coefficients that are adjusted for age, gender, educational level, race/ethnicity (Black, white, Hispanic) and diagnosis (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, other psychosis diagnosis). An examination of the equations in which perceived devaluation-discrimination and daily indignities are entered separately (Equations 1,2,4,5,7 and 8) shows that these measures are consistently related (six of six associations) at least at a trend level to 1) concern about staying in, 2) stigma consciousness, and 3) secrecy. When considered together in Equations 3, 6 and 9, the two variables jointly account for significant increments to explained variance of 9.8%, 15.9% and 13.8% for concern with staying in, stigma consciousness and secrecy, respectively. In order to convey the strength of some of the associations, we categorized the two predictor variables and each of the three outcome variables into high (top quartile) and moderate/low (bottom three quartiles) and used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios. Controlling for diagnosis and sociodemographic variables, a participant who is high on the daily indignities scale has 9.7 (95% CI 2.3 – 41.4) times the odds compared to someone who is moderate or low of also having a high concern with staying in, whereas a participant who is high on the scale of devaluation/discrimination has 5.6 (95% CI 1.3 – 24.9) times the odds compared to someone who is moderate or low of being high in terms of stigma consciousness.

Table 2 shows standardized regression coefficients pertaining to withdrawal (keeping people away) and low self-esteem (keeping people down). For each dependent variable, a first equation (Equations 1 and 3) enters perceived devaluation/discrimination and daily indignities along with controls for diagnosis and sociodemographic variables. A second equation (Equations 2 and 4) adds variables that assess a concern with staying in, stigma consciousness and secrecy.

Concerning withdrawal, Table 2 Equation 1 shows that both perceived devaluation/discrimination (beta = .233) and daily indignities (beta = .342) are significantly associated with a tendency to withdraw from social interactions as a means of avoiding rejection. Together the two variables provide a 19.1% increment to explained variance above controls for diagnosis and sociodemographic variables. Equation 2 adds measures assessing concern with staying in, stigma consciousness and secrecy, further increasing the variance explained by 21.4%, mainly due to a particularly large effect (beta = .496) of secrecy. Further, by comparing the magnitude of the significant coefficients for perceived devaluation/discrimination and daily indignities in Equation 1 to their values in Equation 2 we see that the coefficients for perceived devaluation-discrimination and daily indignities declined by 48% and 36% respectively, suggesting that some large part of the association of these variables is accounted for by the variables added to Equation 2. The results are, therefore, consistent with but do not confirm the possibility that perceived devaluation/discrimination and exposure to daily indignities leads to a concern for secrecy, and that a concern for secrecy leads, in turn, to a tendency to withdraw from social contacts. In order to convey the magnitude of the association between concern with secrecy and tendency to withdraw, we categorized each variable, as before, so that 1 represented the top quartile of each and 0 represented the bottom three quartiles and found that a participant who is high on a concern with secrecy has 10.1 (95% CI 2.8 – 36.1) times the odds compared to someone who is moderate or low on that scale of being high on withdrawal.

Concerning self-esteem, Table 2 Equation 3 shows that controlling for diagnosis and sociodemographic variables, perceived devaluation/discrimination is significantly negatively associated with self-esteem whereas daily indignities are not. Together the two variables account for an increment to explained variance of 8.3%, mainly due to the influence of perceived devaluation/discrimination. Table 2 Equation 4 adds measures assessing concern with staying in, stigma consciousness, and secrecy, further increasing explained variance by 17.6%, mainly due to the effect (beta = −.396) of stigma consciousness. A comparison of the magnitude of the coefficients for devaluation/discrimination in Equations 3 and 4 shows that much of this variable’s association with self esteem (81%) is explained by the variables added in Equation 4, especially stigma consciousnes, a result that is consistent with but does not confirm the possibility that perceived devaluation/discrimination from most people leads to stigma consciousness which then erodes self-esteem. With respect to the magnitude of the effect of stigma consciousness, using the same strategy described above to estimate adjusted odds ratios, we find that a participant who is high on stigma consciousness has 3.14 (95% CI .85 – 11.51) times the odds of low self-esteem compared to someone who is moderate or low on the stigma consciousness scale.

Discussion

We introduced “stigma power,” defining it as the capacity to keep people down, in and/or away by using stigma-related processes. We employed Bourdieu’s (1987; 1990) concepts because they helped us see that the interests of stigmatizers are often “misrecognized,” hidden in processes that are seemingly unrelated to the direct actions of those who would stigmatize. Thus while the exercise of stigma power can be brutishly obvious, it is more generally hidden in processes that are just as potent, but less obviously linked to the interests of stigmatizers.

Having introduced stigma power, we used it to illuminate the situation of people with mental illnesses and the stigma they experience by drawing on a unique data set that included measures of the concepts in question. We identified the main interest of those who stigmatize people with mental illnesses to be “keeping people in” and failing that, keeping them “away” and “down.” We proposed that these interests are only rarely realized through overt and direct actions of stigmatizers but are instead achieved indirectly and covertly through the perceptions and behaviors of the stigmatized. This led us to consider the responses of people with mental illnesses to the pervasive and negative cultural conceptions they confront, asking whether their efforts to protect themselves induce strong concerns with staying in, an inclination to stay away, and a feeling of being downwardly placed. We found that people with psychosis are often aware of the cultural assessment of their social standing and sometimes experience what we called daily indignities. We also identified a high degree of concern about staying within normative boundaries, an inclination to stay away to avoid rejection and a feeling of being downwardly placed in terms of the experience of low self-esteem. Finally, our results are consistent with but do not confirm the possibility that a cascade of circumstances in which stigmatized people, in seeking to avoid rejection by others, accomplish what those others want – keeping them in, down and away.

Considerations Concerning Validity. Clearly, results from this relatively small cross- sectional study cannot confirm the utility of the stigma-power concept. Although the new measures we adapted or developed are an asset for presenting the stigma-power concept, some are used for the first time and should therefore be further tested for evidence of reliability and validity including assessments of the degree of potential overlap in some measures. Moreover, the results are from one specific group (people with psychosis), who were relatively early in their illness experience and currently in treatment in inpatient units when they were recruited, thereby limiting generalization of study results to other groups or to the same group at different times. Additionally the confidence intervals around our point estimates are quite large, and the associations uncovered are potentially subject to alternative interpretations as to direction of causal effect and the possibility of confounding. In light of these limitations, it is important to remember that our intent was to introduce the concept of stigma power rather than to confirm it. With this in mind, we note that the results could have directed us away from the concept. The questionnaire items we created need not have aligned as they did with the concepts of keeping people in, down or away; participants need not have endorsed the questions posed to them; specific questions need not have coalesced into internally consistent scales; and associations between scales need not have cohered with the theoretical expectations -- but to a large degree they did. Thus while our results cannot confirm the utility of the concept, they nevertheless provide supportive evidence of its plausibility and thereby its potential usefulness in future work.

Implications for Structural Stigma. In keeping with the focus of this special issue, the concept of stigma power directs attention to macro-level factors that drive stigma processes. As we see it, stigma power emerges in the cultural system, that is, in a “set of cognitive and evaluative beliefs—beliefs about what is or what ought to be—that are shared by the members of a social system and transmitted to new members” (House, 1981, p. 542). In the specific instance we studied, societal conceptions of people with mental illnesses (perceived devaluation/ discrimination) are just such “cognitive and evaluative beliefs,” and according to the theory this set of beliefs that spur a cascade of responses that induce people with mental illnesses to try to stay in, to move away and/or to feel put down. If this happens, social structures are created, with such structures being defined as a persistent “pattern of social relationships (or pattern of behavioral intention) among the units (persons or positions) in a social system” (House, 1981, p. 542). The resulting social structure, according to the theory, is one in which people with mental illnesses are set apart and pushed down. Our reasoning casts stigma power -- a component of the cultural system – as a factor that creates social structures. At the same time we see the relationship between cultural and structural elements as reciprocal because once social structures are created, members of the public observe the resulting downward placement or exclusion in a way that coheres with or reinforces their interest in, and approach to keeping people in, down or away.

Implications for Future Theory-Testing. A reasonable challenge to the stigma-power concept might be to question the capacity of stigmatizers to influence the stigmatized so as to gain their cooperation in keeping people in, down and away. Our theory claims that the stigmatized are pushed toward enacting the aims of stigmatizers because they want to avoid being associated with existing and generally negative societal conceptions and because they are exposed to daily indignities that remind them of their different and less desirable standing in the social order. But one might argue that these circumstances just happen to achieve the aims of the stigmatizers and that there is no compelling evidence to link these circumstances to the interests of stigmatizers. A response from the standpoint of the theory is that the interests of stigmatizers, though generally misrecognized by the stigmatizers themselves, become particularly evident when hidden processes like the ones we identified weaken and fail to achieve the interests of stigmatizers. In such a circumstance our theory predicts action by stigmatizers to reinvigorate the system of social control. Specifically, we expect an upswing in direct person-to-person discrimination, an increase in daily indignities, and advocacy for social control policies that might bring things back in line. For example, when the possibility of the massive deinstitutionalization of people with psychosis to local communities threatened the capacity to keep such people “away,” strong Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) reactions countered such a possibility and insured that people with severe mental illnesses were located in less desirable sections of the city away from those who wished to exclude them. Future research might test this theoretical proposition at both the individual and policy level by examining instances in which people with psychosis fail to stay within normative boundaries, refuse to stay away and/or do not accept their downward placement.

Implications for Future Research. With respect to future research concerning mental-illness stigma, the current project brings new measures that might be fruitfully employed to better understand the stigma process. Especially the measures relating to “concern with staying in” and “stigma consciousness” point to a conceptual domain that is underdeveloped in the public stigma/self-stigma conceptualization commonly used in this area. These are constructs that are neither the internalization of stereotypes nor public beliefs, but instead point to social psychological predicaments that lie between the self and others that place a toll on many people with mental illnesses. The associations uncovered in this study between these and other important constructs like withdrawal and self-esteem suggest the need to further understand these processes in future research.

Implications for Reducing Stigma. The stigma-power concept identifies the interests of stigmatizers and points to the utility of stigma processes in achieving ends they desire. If we want to change stigma, we need to recognize (and not misrecognize) these interests and address them directly. Broadly speaking they can be directly addressed in two ways; 1) by fundamentally changing stigmatizers so they are less inclined to keep people down, in or away as has been achieved at least to some degree through the civil rights and gay and lesbian liberation movements or 2) by changing the balance of power between stigmatizers and the stigmatized so that stigmatizers are less able to achieve their goals, as has been achieved, again to some extent, through laws banning certain types of discrimination. Neither one of these circumstances is likely to occur as the consequence of a single individually-focused anti-stigma intervention but rather by a long process of change and struggle that involves a multiplicity of actions over a long period of time.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

New measures of mental illness stigma show how people are harmed by the stigma they experience.

Stigma is a form of power that allows people to keep people with mental illnesses down, in and away.

The interests of stigmatizers are achieved through hidden, “misrecognized” mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH74996) and by funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program at Columbia University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Bruce G. Link, Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute

Jo Phelan, Columbia University.

References

- Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. What makes a social class? On the theoretical and practical existence of groups. Berkeley Journal of Sociology. 1987;32:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The Logic of Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology. 2002;9(1):35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’s illusion. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Mougios V, Ayduk O, London B, Shoda Yuichi. Rejection sensitivity and the defensive motivational system: Insights from the startle response to rejection cues. Psychological Science. 2004;15(10):668–673. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson KT. Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter-Framing. New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health and health Care. (This Issue) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L, Phelan Jo C, Link Bruce G. Stigma as a fundmental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:813–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Bellatorre A, Lee Y, Finch B, Muennig P, Fiscella K. Structural stigma and all-cause mortality in sexual minority populations. (This Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Social structure and personality. In: Rosenberg M, Tumer RH, editors. Social psychology: Sociological perspectives. New York: Basic Books; 1981. pp. 525–561. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Leary MR. Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: the functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–208. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout P, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach in the area of the mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–23. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Castille D, Stuber J. Stigma and Coercion in the Context of Outpatient Treatment for People with Mental Illnesses. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. (This Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML. The influence of structural stigma on young sexual minority men’s substance use: Direct effects and possible mechanisms. (This Issue) [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and discrimination: One animal or two? Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Lucas JW, Ridgeway CL, Taylor CJ. Stigma, status, and population health. (This Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(1):114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:652–666. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review. 1997;62:660–72. [Google Scholar]

- Scheff TJ. Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1966. (reprinted 1984) [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair SJ, Blais MA, Gansler DA, Sandberg E, Bistis K, LoCicero A. Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Overall and across demographic groups living within the United States. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2010;33(1):56–80. doi: 10.1177/0163278709356187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CJ. Physiological stress response to loss of social influence and threats to masculinity. (This Issue) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Self-labeling processes in mental illness: The Role of Emotional Deviance. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;92:221–49. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.