Abstract

A method to simultaneously measure oxygenation in vascular, intracellular, and mitochondrial spaces from optical spectra acquired from muscle has been developed. In order to validate the method, optical spectra in the visible and near infrared regions (600–850 nm) were acquired from solutions of myoglobin, hemoglobin, and cytochrome oxidase that included Intralipid as a light scatterer. Spectra were also acquired from the rabbit forelimb during ischemia. Three partial least squares (PLS) analyses were performed on second-derivative spectra, each separately calibrated to myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, or cytochrome aa3 oxidation. The three variables were measured from in vitro and in vivo spectra that contained all three chromophores. In the in vitro studies, measured values of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation had standard errors of 7.4%, 3.8%, and 3.9%, respectively, with little cross-talk between the measurements. During ischemia in the rabbit forelimb, hemoglobin desaturated first, followed by myoglobin, while cytochrome aa3 reduction occurred last. The ability to simultaneously measure oxygenations in the vascular, intracellular, and mitochondrial compartments will be valuable in physiological studies of muscle metabolism and in clinical studies when oxygen supply or utilization are compromised.

Subject terms: Near infrared spectroscopy, visible spectroscopy, tissue oxygenation, muscle, blood, mitochondria

INTRODUCTION

Many investigators have used optical spectroscopy to measure tissue oxygenation and cytochrome redox states. The harmless non-ionizing radiation from light and the relatively inexpensive instrumentation make noninvasive optical measurements attractive for basic studies in physiology and pathology, and for clinical use. Currently, pulse oximetry, which measures hemoglobin saturation in arterial blood, is commonly used in the hospital setting to evaluate oxygen sufficiency. If oxygenation in the local vascular, intracellular, and mitochondrial spaces could also be known, further refinements to assess efficacies of therapies would be possible in a variety of pathologies. This is especially important in diseases where oxygen supply and/or utilization are compromised, as in shock, peripheral vascular disease, or anemia.

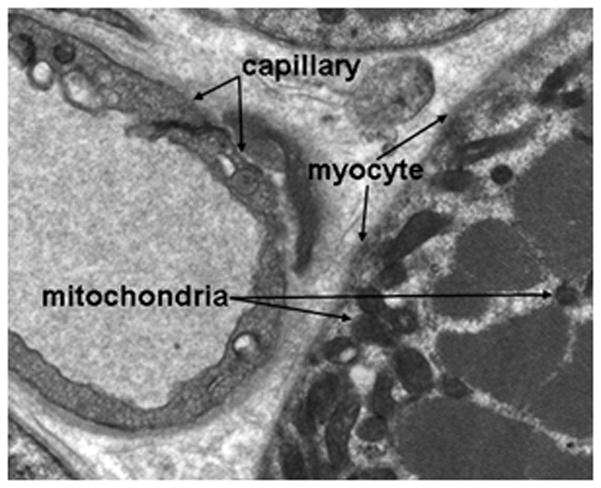

The main chromophores in optical spectra of muscle are hemoglobin, myoglobin, and the cytochromes, each located in a separate anatomical compartment (Fig. 1). The hemoglobin signal reflects the oxygenation of blood in the local vasculature and is a weighted average of arterial, capillary, and venous blood. Myoglobin is an intracellular protein in muscle cells that facilitates the diffusion of oxygen from the cell membrane to the mitochondria.1 Both myoglobin and hemoglobin have oxygen-bound and -unbound states that are spectroscopically distinct. In the mitochondria, cytochrome oxidase is the terminal enzyme in the electron transport chain that catalyzes the reaction where oxygen is reduced to water. As electrons travel down the transport chain, protons are pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Energy stored in this electrochemical gradient is used to make ATP from ADP. Cytochrome oxidase has visible absorbances sensitive to the redox state of the heme aa3 at ~ 605 nm, and it also has absorbances in the near infrared (NIR) that are sensitive to the redox state of its copper (CuA) center at ~ 830 nm.

Figure 1.

Electron micrograph showing the anatomic relationships between the vascular capillary space, the myocyte, and the mitochondria in a skeletal muscle sample. Optical spectroscopy can measure oxygenation at three critical points in the pathway that are in distinct physical compartments: hemoglobin saturation in the vasculature, myoglobin saturation within myocytes, and cytochrome oxidation within mitochondria.

Most of the previous optical spectroscopic studies on muscle oxygenation made measurements at 2, 4, or 6 wavelengths. With so few wavelengths, contributions from hemoglobin and myoglobin cannot be separated because their absorbance spectra are so similar.2–5 There remains significant controversy as to whether 2- or 4-wavelength spectroscopy indicates only hemoglobin saturation2,3 or whether myoglobin saturation contributes significantly to the measured signal.5,6 Other studies have used a 2-, 4-, or 6-wavelength methodology to yield relative changes in cytochrome oxidase redox states in hemoglobin-free perfused muscle7,8 or in the brain, in the presence of hemoglobin.4,9–11 Recently, studies that analyze a full spectrum have measured cytochrome oxidase redox states in brain using linear regression to quantify hemoglobin saturation and concentration, as well as cytochrome oxidase redox states.12,13

Our laboratory has used an approach called partial least squares (PLS) analysis to quantify myoglobin and hemoglobin saturations in cardiac14–16 and skeletal muscle17–19 from spectra acquired in the visible and NIR regions. We have also shown that cytochrome c oxidation can be determined in the visible region in buffer-perfused hearts.20 In the present paper, we have extended these analyses to include the measurement of cytochrome aa3 oxidation states in vivo.

Problems encountered by any continuous-wave method include unknown scattering coefficients and optical pathlengths, the significant overlap of absorbances from different chromophores present in tissue, and the relatively low concentrations of cytochromes relative to myoglobin and hemoglobin. The goal of the present study was to assess how well PLS could overcome these difficulties to quantify hemoglobin saturation, myoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation simultaneously in blood-perfused skeletal muscle. Calibrations and tests of accuracy in the saturation and oxidation measurements were done in vitro using myoglobin, hemoglobin, and cytochrome oxidase solutions with Intralipid as a light scatterer. Subsequently, measurements were acquired in vivo in the rabbit forelimb.

METHODS

In vitro solution preparation

Lyophilized myoglobin (M-1882, Sigma Chemical) was dissolved in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 to form oxidized metmyoglobin. In order to reduce metmyoglobin to the physiologically active state, excess sodium dithionite was added to the solution that was then separated on a 25-cm Sephadex chromatography column (G-25-150, Sigma Chemical) at 4°C. Myoglobin solutions were equilibrated with room air to form oxymyoglobin (MbO2), which was further diluted with phosphate buffer to a final concentration of 150 μM. Distinct solutions of identical myoglobin concentrations were made with Intralipid concentrations of 2% and 3%, such that the scattering level varied around that found in tissue. Deoxymyoglobin (Mb) was formed by addition of excess sodium dithionite.

Fresh sheep red blood cells were lysed by dilution with distilled water and added to Intralipid-containing solutions as above. Final solutions of 50 and 100 μM hemoglobin, covering the range of hemoglobin found in skeletal muscle,21,22 were used. Solutions were gently bubbled with oxygen to make oxyhemoglobin (HbO2). A solution at each hemoglobin concentration was combined separately with 2% and 3% Intralipid concentrations. Deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) was made by addition of excess sodium dithionite.

Cytochrome oxidase was purified from beef heart using the method of Yonetani.23 Cytochrome oxidase was then diluted in buffer containing Intralipid at concentrations of 2% and 3%. Oxidized (cyt aa3ox) and reduced (cyt aa3red) forms were prepared by addition of potassium ferricyanide and sodium dithionite, respectively. Each solution had a final concentration of approximately 6.5 μM.

Rabbit forelimb measurements

All experiments were performed in accordance with the University of Washington Animal Care Committee regulations. Two New Zealand White rabbits (mean weight 2.4 kg) were anesthetized with an initial dose of ketamine (35mg/kg) and xylazine (5mg/kg) delivered intramuscularly to the femoral region. The neck was shaved before a tracheostomy was performed. The animals were mechanically ventilated at 24 breaths/min (model 708, Harvard Apparatus) on 100% oxygen. A 1.5-Fr microtip catheter transducer (model SPR 612, Millar Instruments) was inserted into the carotid artery to monitor blood pressure. Supplemental doses of ketamine were administered at 30-min intervals. Blood gases from samples taken from the carotid artery were measured by an I-Stat analyzer (cartridge EC4, Abbott Laboratories). Ventilation rate was adjusted and bicarbonate was administered to maintain physiological blood gas values.

After shaving the forelimb, the biceps brachii muscle was exposed by opening the skin, and the optical probe was placed directly on the muscle. Care was taken to avoid placing the optical probe over a large vein or artery, so that the hemoglobin signal arose primarily from arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Silver barbed wires (25 gauge) were placed near the origin and insertion of the muscle group for muscle stimulation.

Tissue temperature was monitored and controlled. A fine wire thermocouple (Mallinckrodt Corp.) was placed proximal to the fiber optic probe and sampled muscle tissue. Local temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C using a proportional temperature controller (Barnant, Barrington IL) and hot air blower positioned 20 cm from the forelimb.

Spectral acquisition began after animals were instrumented and stable. Spectra were collected continuously during 5 min of oxygen ventilation and 5 min of ventilation with room air to achieve a normoxic state. Ventilation with oxygen was resumed for another 5 min, followed by forelimb ischemia. Continuous spectra were acquired and animals were ventilated with oxygen throughout the remainder of the study, during ischemia and recovery.

Ischemia was induced in the forelimb by pulling a 0.5″-wide strap tight, proximal to the optical probe. The strap was held in place with a clamp for the 10-min ischemic period. After a recovery period of 10–15 min, complete deoxygenation of the forelimb was attained with a combination of ischemia and muscle stimulation for 10 min. Pulses were 5V of 5 ms duration, with a frequency of 2 Hz (model SD9, Grass Technologies). Animals were euthanized with a pentobarbital anesthetic overdose into the ear vein at the end of the experiments.

Optical spectrometer

A custom-built fiber optic probe with a 1.75-mm separation between transmitting and receiving fibers was used to assure an average depth of light penetration of 0.4–0.5 mm into the muscle.24 The probe had a concentric design where optical fibers transmitting light to the sample were arranged in a ring around a central bundle of fibers that brought reflected light from the tissue to the spectrometer.25 Illumination from a constant-intensity quartz-tungsten-halogen white light source (model 66184, Oriel Instruments) was passed through a 1.0-in water filter and an electromechanical shutter (model 76995, Oriel Instruments) before transmission to the optical probe to decrease tissue heating. Constant light intensity was ensured by a photo-feedback system (model 68850, Oriel Instruments). Optical spectra were acquired with a diffraction spectrograph (model 100S, American Holographics) equipped with a 512-pixel photodiode array (model C4350, Hamamatsu) using a 200-ms exposure time. Each pixel spanned 1 nm in the spectrum. Spectral acquisition was gated to acquire data at 2.5-s intervals, and the data were converted to digital form using a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (model AT-MIO-16X, National Instruments).

Spectral preprocessing

All calibration set spectra and all test spectra (in vitro and in vivo) were preprocessed by taking second derivatives with respect to wavelength. Discrete second differences were used to approximate second derivatives. Spectra were first smoothed with a window of nine points, corresponding to a span of 9 nm. The second difference at each point in the spectrum is equal to the sum of the values ±7 nm from that wavelength minus twice the value at the central wavelength. Using second-derivative spectra eliminates baseline offsets and removes much of the effect of scattering on the spectra.18

Spectral analysis by partial least squares (PLS)

Myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation were determined from each in vitro or in vivo test spectrum by three separate PLS analyses in the wavelength range 600–850 nm, encompassing 250 spectral points. PLS is an extension of linear regression that is useful for extracting information on specific spectral components from complex spectra.26 The algorithm generates a set of calibration coefficients at each wavelength when calibrated with spectra from solutions with known values of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, or cytochrome aa3 oxidation. The dot product of the calibration coefficients that correspond to myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, or cytochrome aa3 oxidation with a test spectrum determines the unknown saturation or oxidation for that spectrum. When trained this way, the PLS algorithm interprets spectral variations with time as changes in myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, or cytochrome aa3 oxidation, and not as changes in concentration. In the short time span of an experiment, myoglobin and cytochrome aa3 concentrations are not expected to vary, but hemoglobin concentrations can vary greatly with changes in blood volume during reactive hyperemia. Therefore, hemoglobin saturation values measured during hyperemia were not used. The PLS algorithm is described more fully in Refs. 25–27.

In vitro calibration set spectra containing the three chromophores were obtained by mathematically adding spectra of solutions acquired at the extremes of saturation or oxidation,25 using the equation:

| (1) |

where spec(i) is the ith calibration set spectrum. The pairs of coefficients associated with each chromophore were random numbers between 0 and 1. Each pair summed to 1 so that composite spectra with intermediate saturations and oxidations at constant concentrations were obtained. Myoglobin saturation is defined as [α/(α + β)] × 100%, hemoglobin saturation is defined by [δ/(δ + γ)] × 100%, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation is equal to [σ/(σ + τ)] × 100%. Known values of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation for each spectrum were used to calibrate PLS.

Three separate calibration sets were used to determine the calibration coefficients for myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation. In the myoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation calibration sets of 400 spectra each, both scattering levels and both hemoglobin concentrations were represented to mimic chromophore concentrations and scattering coefficients found in muscle. Two hemoglobin concentrations were included to make measurements of myoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation less sensitive to changes in total hemoglobin concentration. The hemoglobin saturation calibration set was composed of 300 spectra with both scattering levels. In this calibration set, all spectra had a hemoglobin concentration of 100 μM so that the PLS model would be sensitive to hemoglobin saturation and not to hemoglobin concentration. A PLS model was formed from each calibration set by providing the algorithm with the calibration spectra and the known associated values for myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, or cytochrome aa3 oxidation. In this way, each PLS model was sensitive to a single variable, and spectral variations associated with the other chromophores were treated as uncorrelated noise. The optimal number of factors for each chromophore was determined by a PRESS (Prediction Error Sum of Squares) analysis.26 The calibration coefficient vectors for myoglobin and hemoglobin both encompass five factors, while that for cytochrome oxidase encompasses seven factors.

The relative saturation and oxidation values from the PLS analyses of the in vivo spectra were scaled by determining two points of known saturations or oxidations in each animal.18 The maximum values for myoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation obtained during reactive hyperemia after the release of the ischemic cuff were assumed to be 100%. Hemoglobin was assumed to be 100% saturated at rest while the animal breathed oxygen. Myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation were all assumed to be completely desaturated or reduced at the end of the 10-min period of ischemia combined with muscle stimulation. This assumption is supported by the finding that all the variables approached an asymptote toward the end of this period. All PLS values from a single animal were scaled between these maximum and minimum endpoint values, allowing PLS results from different animals to be compared.

Intracellular cytoplasmic oxygen tension is related to myoglobin saturation by the Hill equation:

| (2) |

where P50 for myoglobin at 37 °C is 2.39 Torr28 and Mbsat is myoglobin saturation.

Statistical tests for match between in vitro calibration set and in vivo muscle spectra

The accuracy of PLS values for myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation from in vivo spectra depends on how similar the in vitro calibration set spectra are to the in vivo spectra. Two statistical tests were used to demonstrate that the in vitro calibration set spectra resemble in vivo spectra from the rabbit limb: calculation of Mahalanobis distances and the residual ratio test.

To calculate Mahalanobis distances, a principal component analysis was done on the second-derivative calibration set spectra. Using the first n principal components, scores were determined for each second-derivative in vivo spectrum. A Mahalanobis distance is defined as the n-dimensional geometric distance between a spectrum’s scores and the mean of scores from the calibration set spectra, where n is the number of principal components used. The value of n is chosen as the number of factors used in the PLS model. Since the scores of an in vivo spectrum are calculated from the principal components derived from the calibration set, the Mahalanobis distance quantitatively represents the difference in spectral character between this spectrum and the spectra in the calibration set. Each Mahalanobis distance is associated with a probability value according to the chi-squared distribution. Spectra with a probability value between 1.0 and 0.05 are classified as “members” of the calibration set, and those with probability values less than 0.05 are labeled as “outliers”.29

Another test for the similarity between calibration set spectra and in vivo spectra is the residual ratio test. Both the in vitro calibration set spectra and the in vivo spectra are reconstructed from the first n loadings obtained from principal component analysis of the calibration set. The residual for each reconstructed spectrum, both in vitro and in vivo, is determined as the difference at each wavelength between the original and reconstructed spectrum. The residual ratio for an in vivo spectrum is the ratio of the sum of squares of residuals for that spectrum to the mean sum of squares of residuals in all of the calibration set spectra. A residual ratio of greater than 3–4 for a given in vivo spectrum indicates that the PLS model is not relevant for that spectrum.30

Statistical analyses

All spectral analysis was done in Matlab (The MathWorks, Inc.), while all statistics and curve fits were done using Origin (Originlab Corp.).

RESULTS

The feasibility of measuring myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation from a single spectrum was tested in vitro and then was validated in the rabbit forelimb. Fig. 2A shows component spectra from in vitro solutions for the three chromophores in the spectral range 600–850 nm. The overlapping absorbances make it difficult to separate the components, but in the second derivative with respect to wavelength (Fig. 2B), the component spectra become more distinct. Using second derivative spectra has two important advantages: improving the definition between spectral peaks and reducing the effect of scattering on the spectra.

Figure 2.

Spectra of pure components of major chromophores found in muscle. A) Reflectance spectra of in vitro solutions of oxyhemoglobin (HbO2), deoxyhemoglobin (Hb), oxymyoglobin (MbO2), deoxymyoglobin (Mb), oxidized cytochrome aa3 (cyt aa3ox), and reduced cytochrome aa3 (cyt aa3red). All solutions contained 2% Intralipid as a light scatterer. B) Second derivatives with respect to wavelength of spectra in A. Absorbances in the second-derivative spectra of Hb and Mb and of cyt aa3ox and cyt aa3red are better defined than in the original spectra.

Mahalanobis distances were calculated for all 522 in vivo spectra from the two animals using the first five principal components of the calibration set. None of the spectra were classified as outliers when compared to the calibration set using the chi-squared distribution. Residual ratios were also calculated for the 522 in vivo spectra from the first five principal components of the calibration set. All of the spectra had residual ratios that were less than 3, indicating that the PLS model based on the in vitro calibration set is appropriate for these in vivo spectra.

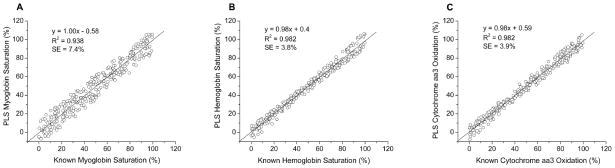

A test set of 300 in vitro spectra was formed using Eq. 1 with random coefficients that were different from the calibration sets. The test set was equivalent, but not identical, to the calibration sets. The myoglobin and cytochrome aa3 concentrations in the test set were the same as in the calibration sets, 150 μM and 6.5 μM, respectively. The hemoglobin concentration was 100 μM in all spectra, and both scattering levels were represented. When the test set spectra were applied to each of the three calibration coefficient vectors, good accuracy was achieved for all measured variables (Fig. 3). The standard errors (SE) of the predicted values were 7.4%, 3.8%, and 3.9% for myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation, respectively.

Figure 3.

In vitro measurements of A) myoglobin saturation, B) hemoglobin saturation, and C) cytochrome aa3 oxidation. Measurements in all panels were determined from the same test set spectra. Good accuracy was obtained in all three. Standard errors (SE) were 7.4%, 3.8%, and 3.9% for myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation, respectively. Correlation coefficients (R2) are also given. Lines of unity are shown for reference.

In order to assess the amount of cross-talk between measurements of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation made from each test set spectrum, pairwise comparisons of the measurements shown in Fig. 3 are plotted in Fig. 4. Each data point represents a test set spectrum where myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation were varied randomly. The lack of correlation between the variables over the full ranges from 0 – 100% indicates little cross-talk between the measurements.

Figure 4.

Correlations between measurements shown in Figure 3. A) Myoglobin vs. hemoglobin saturation, B) myoglobin saturation vs. cytochrome aa3 oxidation, and C) hemoglobin saturation vs. cytochrome aa3 oxidation. Poor correlations were found between measurements made from the same test set spectra, showing that measurements of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation have little cross-talk between them. Linear fits between the variables are shown. Correlation coefficients (R2) and standard deviations of the fits (SD) are given.

Despite their very similar absorbance spectra (Fig. 2), myoglobin and hemoglobin saturation measurements were not correlated. Myoglobin and hemoglobin saturations can be determined independently from the same spectrum (Fig. 4A). The correlations between cytochrome aa3 oxidation and both myoglobin and hemoglobin saturations were also very poor. Cytochrome aa3 oxidation can be determined with very little cross-talk from the other chromophores that are found in tissue at much greater concentrations (Figs. 4B and 4C).

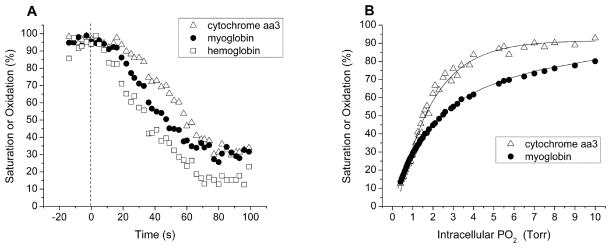

Fig. 5A shows the time courses of myoglobin and hemoglobin desaturation and cytochrome aa3 reduction during ischemia in one animal. Hemoglobin saturation declined ~ 5 s after the onset of ischemia. Myoglobin saturation remained at baseline levels for ~ 7.5 s before declining, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation remained constant for ~ 17.5 s before beginning to decrease. The temporal separation between the decreases in the measurements is supportive evidence that separate measures of the three chromophores can be made in vivo.

Figure 5.

A) In vivo measurements of hemoglobin saturation, myoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation during ischemia in the forelimb of one rabbit (onset of ischemia is at Time = 0). Measurements in three anatomical compartments made from each spectrum are separable. Hemoglobin desaturated first, followed by myoglobin, followed by cytochrome aa3 reduction. Temporal resolution is ~ 2.5 s. B) Oxygen dependence of cytochrome aa3 oxidation and myoglobin saturation in blood-perfused skeletal muscle in vivo in two animals. Intracellular PO2 was determined from measured myoglobin saturations and the previously determined myoglobin oxygen dissociation curve.28 The curves show that cytochrome aa3 has a greater oxygen affinity than myoglobin. The paired myoglobin saturations and cytochrome aa3 oxidations at each value of intracellular PO2 arose from the same spectra and emphasize the good separability of the measurements. The curve through the cytochrome aa3 data is a fit to an asymptotic exponential of the form y = a − bcx. The curve through myoglobin saturations is the Hill equation (Eq. 2) using a previously determined myoglobin p50 of 2.39 Torr at 37 °C.28 Hemoglobin saturation is not shown because it is in a separate compartment, the vascular space.

The oxygen dependence of myoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation are shown in Fig. 5B. Intracellular PO2 values were calculated from myoglobin saturations using Eq. 2. Myoglobin saturations and cytochrome aa3 oxidations measured during an ischemic bout in each of two rabbits were combined and binned along the PO2 axis. The relationship between cytochrome aa3 and myoglobin curves is consistent with the greater oxygen affinity of cytochrome aa3 compared to myoglobin. The line through the cytochrome aa3 oxidation data is a fit to an asymptotic exponential of the form y = a − bcx, while the line through myoglobin saturations is the Hill equation (Eq. 2).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that oxygenation in three anatomically separate compartments can be measured simultaneously from a single optical spectrum acquired from muscle. In the NIR, Mb and Hb absorbances at ~ 760 nm are the most distinct spectral features that contribute to determining myoglobin and hemoglobin saturations (Fig. 2A). In the second derivative (Fig. 2B), the absorbances of Mb and Hb become narrower and better separated from each other when compared to the raw spectra. The ~ 4-nm shift between Mb and Hb allows myoglobin and hemoglobin saturations to be independently determined when a spectrum of wavelengths are measured and analyzed.15,17,19

The second derivative also helps to distinguish oxidized and reduced cytochrome aa3 spectra. The visible absorbance of cytochrome oxidase heme aa3 at 605 nm was used to measure oxidation because it is larger, narrower, and easier to quantify than the CuA absorbance of cytochrome oxidase in the NIR at 830 nm. Other investigators have measured the NIR absorbance of the CuA center in brain studies because it has good photon depth penetration.12,13 Redox states of heme aa3 and CuA simultaneously reduce in response to a decreased oxygen supply, but heme aa3 is usually more reduced than CuA.31

In vitro measurements of myoglobin saturation in the presence of hemoglobin, cytochrome oxidase, and a scatterer were quite accurate, and the SE of the measured values was 7.4% (Fig. 3A). When measurements of hemoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation were made from the same spectra, the SE of the measured values for hemoglobin saturation was 3.8% and was 3.9% for cytochrome aa3 oxidation (Figs. 3B and 3C).

Pairwise plotting of myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation values obtained from each test set spectrum shows that there is little cross-talk between the measurements (Fig. 4). Since the saturations of myoglobin and hemoglobin and the oxidation of cytochrome oxidase were randomly varied in the test set spectra, many of the spectra represent conditions that are not physiological. Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate that whether the saturations and oxidations vary together or not, the three variables can be measured accurately and independently of one another, with little cross-talk between them.

Unknown optical pathlengths in tissue have hampered continuous-wave optical measurements of tissue chromophores, especially in cases when only a few wavelengths are measured. For example, changes in blood volume can cause 2-wavelength cytochrome redox measurements in brain to vary without an actual change in cytochrome redox.32 Our approach includes removing much of the effect of scattering on the spectra by using second-derivative spectra.18 Also, when various scattering coefficients and hemoglobin concentrations are included in the calibration set spectra, PLS calibration vectors become relatively insensitive to them.25

Because chromophore concentrations and scattering coefficients are unknown in vivo, and are likely to be different from those in the in vitro calibration set spectra, PLS only provides relative myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation values. In each animal, PLS values obtained during the study were scaled with PLS values measured at two known end point physiological states. Deoxygenated and reduced conditions were produced physiologically by a 10-min period of ischemia and muscle stimulation. Myoglobin saturation was ~ 8% lower at the end of 10 min of combined ischemia and muscle stimulation than with 10 min of ischemia alone. Similarly, hemoglobin saturations were ~ 5% lower and cytochrome aa3 oxidations were ~ 8% lower after ischemia and stimulation when compared to values measured after ischemia alone.

The upper end points for myoglobin saturation and cytochrome aa3 oxidation were obtained during reactive hyperemia upon release of the tourniquet. If myoglobin saturations and cytochrome oxidations during reactive hyperemia were actually less than 100%, the scaled PLS values are overestimates.

Hemoglobin saturation was assumed to be 100% while the animal was at rest and breathing oxygen. PLS values for hemoglobin saturation during reactive hyperemia, while higher than those measured at rest, were not used since the PLS analysis assumes that total hemoglobin concentration is constant and that spectral changes are due to changes in hemoglobin saturation. Hemoglobin saturation values reflect a weighted average of saturations in arterial, capillary, and venous blood. In hyperoxia in resting muscle, hemoglobin saturation throughout the vascular space is very high. In the isolated dog gastrocnemius muscle at rest, arterial and venous oxygen tensions were 509 and 285 Torr, respectively, during breathing with 100% oxygen,33 much higher than the P50 of 30 Torr in canine blood at 37°C.34 The corresponding arterial and venous hemoglobin saturations were 99.97% and 99.85%, respectively.

Ischemia in the rabbit forelimb caused a decline in all three variables, and demonstrated in vivo that myoglobin saturation, hemoglobin saturation, and cytochrome aa3 oxidation can be separately determined from each spectrum (Fig. 5A). With a temporal resolution of 2.5 s, hemoglobin saturation began to decrease first, followed by myoglobin saturation, and finally, by cytochrome aa3 oxidation. These results are consistent with other in vivo studies. Hemoglobin desaturated before cytochrome oxidase began to reduce during anoxia in the piglet brain,13 and in the rat brain with hypoxia.9 NMR measurements showed that myoglobin desaturation lagged hemoglobin desaturation during ischemia in the human gastrocnemius.5

There is disagreement in the literature about whether cytochrome oxidase is fully oxidized35,36 or ≥10% reduced37 in normoxia. By averaging the last 1.5 min of data from the 5 min period of room air ventilation, we found that cytochrome aa3 oxidation was 92 % (n= 2).

Cytochrome aa3 oxidation has been measured in hemoglobin-free skeletal muscle7 and myocardium8 where cytochrome oxidase oxidation was equal to myoglobin saturation at all values of perfusate oxygen tension as it decreased from fully oxygenated to fully deoxygenated. These observations do not agree with the in vitro measurement of cytochrome aa3 oxygen affinity indicating that cytochrome affinity is greater than that of myoglobin.38 These observations also conflict with the general idea that oxygen affinity increases as oxygen flows down the hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome cascade.1 The in vivo oxygen dependence of cytochrome aa3 oxidation using the present method is shown in Fig. 5B. The simultaneously determined in vivo measurements of cytochrome aa3 oxidation and myoglobin saturation indicate that the oxygen affinity of cytochrome aa3 is greater than the oxygen affinity of myoglobin. The ability to simultaneously measure cytochrome aa3 oxidation and intracellular oxygen tension via myoglobin saturation will allow the unambiguous study of the in vivo oxygen affinity of cytochrome aa3.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents a proof of principle that PLS analysis of optical spectra yields separable and simultaneous in vivo measurements of oxygenation in the local vasculature (hemoglobin), inside myocytes (myoglobin), and within the mitochondrial compartment (cytochrome aa3). The ability to track oxygen along its pathway from the vasculature to the mitochondria will be useful in improving understanding of oxygen transport and utilization in tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH 5RO1HL072011, CHRMC Steering Committee Award #24512, and a grant from the McMillen Foundation. The electron micrograph was kindly provided by Joe C. Rutledge, MD, of Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, Washington.

References

- 1.Wittenberg JB, Wittenberg BA. Myoglobin function reassessed. J Exp Biol. 2003;206(Pt 12):2011–2020. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancini DM, Bolinger L, Li H, Kendrick K, Chance B, Wilson JR. Validation of near-infrared spectroscopy in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77(6):2740–2747. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers DE, Anderson LD, Seifert RP, Ortner JP, Cooper CE, Beilman GJ, Mowlem JD. Noninvasive method for measuring local hemoglobin oxygen saturation in tissue using wide gap second derivative near-infrared spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10(3):034017. doi: 10.1117/1.1925250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piantadosi CA, Hemstreet TM, Jobsis-Vandervliet FF. Near-infrared spectrophotometric monitoring of oxygen distribution to intact brain and skeletal muscle tissues. Crit Care Med. 1986;14(8):698–706. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran TK, Sailasuta N, Kreutzer U, Hurd R, Chung Y, Mole P, Kuno S, Jue T. Comparative analysis of NMR and NIRS measurements of intracellular PO2 in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276(6 Pt 2):R1682–1690. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.6.R1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoofd L, Colier W, Oeseburg B. A modeling investigation to the possible role of myoglobin in human muscle in near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurements. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;530:637–643. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seiyama A, Maeda N, Shiga T. Optical measurement of perfused rat hindlimb muscle with relation of the oxygen metabolism. Jpn J Physiol. 1991;41(1):49–61. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.41.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamura M, Oshino N, Chance B, Silver IA. Optical measurements of intracellular oxygen concentration of rat heart in vitro. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;191(1):8–22. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoshi Y, Hazeki O, Kakihana Y, Tamura M. Redox behavior of cytochrome oxidase in the rat brain measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83(6):1842–1848. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science. 1977;198(4323):1264–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji M, Naruse H, Volpe J, Holtzman D. Reduction of cytochrome aa3 measured by near-infrared spectroscopy predicts cerebral energy loss in hypoxic piglets. Pediatr Res. 1995;37(3):253–259. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper CE, Delpy DT, Nemoto EM. The relationship of oxygen delivery to absolute haemoglobin oxygenation and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase redox state in the adult brain: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Biochem J. 1998;332(Pt 3):627–632. doi: 10.1042/bj3320627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springett R, Newman J, Cope M, Delpy DT. Oxygen dependency and precision of cytochrome oxidase signal from full spectral NIRS of the piglet brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(5):H2202–2209. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenkman KA. Cardiac performance as a function of intracellular oxygen tension in buffer-perfused hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(6):H2463–H2472. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schenkman KA, Marble DR, Burns DH, Feigl EO. Optical spectroscopic method for in vivo measurement of cardiac myoglobin oxygen saturation. Appl Spectrosc. 1999;53(3):332–338. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ejike JC, Arakaki LS, Beard DA, Ciesielski WA, Feigl EO, Schenkman KA. Myocardial oxygenation and adenosine release in isolated guinea pig hearts during changes in contractility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(5):H2062–H2067. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00777.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arakaki LSL, Burns DH, Kushmerick MJ. Accurate myoglobin oxygen saturation by optical spectroscopy measured in blood-perfused rat muscle. Appl Spectrosc. 2007 doi: 10.1366/000370207781745928. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arakaki LSL, Kushmerick MJ, Burns DH. Myoglobin oxygen saturation measured independently of hemoglobin in scattering media by optical reflectance spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 1996;50(6):697–707. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcinek DJ, Ciesielski WA, Conley KE, Schenkman KA. Oxygen regulation and limitation to cellular respiration in mouse skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(5):H1900–H1908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00192.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenkman KA. Cytochrome c oxidation determined by multiwavelength optical spectral analysis in the isolated perfused heart. Proc SPIE. 2002;4613:278–285. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akeson A, Biorck G, Simon R. On the content of myoglobin in human muscles. Acta Med Scand. 1968;183(4):307–316. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1968.tb10482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doornbos RM, Lang R, Aalders MC, Cross FW, Sterenborg HJ. The determination of in vivo human tissue optical properties and absolute chromophore concentrations using spatially resolved steady-state diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44(4):967–981. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/4/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonetani T. Cytochrome oxidase from beef heart. Biochem Prep. 1966;11:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui W, Kumar C, Chance B. Experimental study of migration depth for the photons measured at sample surface. Proc SPIE. 1991;1431:180–191. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schenkman KA, Marble DR, Feigl EO, Burns DH. Near-infrared spectroscopic measurement of myoglobin oxygen saturation in the presence of hemoglobin using partial least-squares analysis. Appl Spectrosc. 1999;53(3):325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haaland DM, Thomas EV. Partial least-squares methods for spectral analyses.1. Relation to other quantitative calibration methods and the extraction of qualitative information. Anal Chem. 1988;60(11):1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arakaki LSL, Burns DH. Multispectral analysis for quantitative measurements of myoglobin oxygen fractional saturation in the presence of hemoglobin interference. Appl Spectrosc. 1992;46(12):1919–1927. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenkman KA, Marble DR, Burns DH, Feigl EO. Myoglobin oxygen dissociation by multiwavelength spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82(1):86–92. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah NK, Gemperline PJ. A program for calculating Mahalanobis distances using principal component analysis. Trends Anal Chem. 1989;8(10):357–361. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller CE. Chemometrics for on-line spectroscopy applications - theory and practice. J Chemom. 2000;14(5–6):513–528. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomura Y, Matsunaga A, Tamura M. Optical characterization of heme a + a3 and copper of cytochrome oxidase in blood-free perfused rat brain. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;82(2):135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaManna JC. The redox state of cytochrome oxidase in brain in vivo: an historical perspective. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;530:535–546. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grassi B, Gladden LB, Stary CM, Wagner PD, Hogan MC. Peripheral O2 diffusion does not affect V(O2) on-kinetics in isolated in situ canine muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85(4):1404–1412. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cambier C, Wierinckx M, Clerbaux T, Detry B, Liardet MP, Marville V, Frans A, Gustin P. Haemoglobin oxygen affinity and regulating factors of the blood oxygen transport in canine and feline blood. Res Vet Sci. 2004;77(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bashford CL, Barlow CH, Chance B, Haselgrove J, Sorge J. Optical measurements of oxygen delivery and consumption in gerbil cerebral cortex. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(5):C265–271. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.242.5.C265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inagaki M, Tamura M. Preparation and optical characteristics of hemoglobin-free isolated perfused rat head in situ. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1993;113(6):650–657. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaManna JC, Sick TJ, Pikarsky SM, Rosenthal M. Detection of an oxidizable fraction of cytochrome oxidase in intact rat brain. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(3 Pt 1):C477–483. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.3.C477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oshino N, Sugano T, Oshino R, Chance B. Mitochondrial function under hypoxic conditions: the steady states of cytochrome alpha+alpha3 and their relation to mitochondrial energy states. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;368(3):298–310. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(74)90176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]