Lin et al. generate Plasmodium berghei mutants lacking enzymes critical to hemoglobin digestion. A double gene deletion mutant lacking enzymes involved in the initial steps of hemoglobin proteolysis is able to replicate inside reticulocytes of infected mice with limited hemoglobin degradation and no hemozoin formation, and moreover, is resistant to the antimalarial drug chloroquine.

Abstract

Most studies on malaria-parasite digestion of hemoglobin (Hb) have been performed using P. falciparum maintained in mature erythrocytes, in vitro. In this study, we examine Plasmodium Hb degradation in vivo in mice, using the parasite P. berghei, and show that it is possible to create mutant parasites lacking enzymes involved in the initial steps of Hb proteolysis. These mutants only complete development in reticulocytes and mature into both schizonts and gametocytes. Hb degradation is severely impaired and large amounts of undigested Hb remains in the reticulocyte cytoplasm and in vesicles in the parasite. The mutants produce little or no hemozoin (Hz), the detoxification by-product of Hb degradation. Further, they are resistant to chloroquine, an antimalarial drug that interferes with Hz formation, but their sensitivity to artesunate, also thought to be dependent on Hb degradation, is retained. Survival in reticulocytes with reduced or absent Hb digestion may imply a novel mechanism of drug resistance. These findings have implications for drug development against human-malaria parasites, such as P. vivax and P. ovale, which develop inside reticulocytes.

Clinical symptoms of malaria are associated with Plasmodium infection of RBCs. Human Plasmodium falciparum parasites catabolize more than half of the hemoglobin (Hb) in the RBCs (Goldberg, 2005). The amino acids derived from Hb proteolysis are used for protein synthesis and energy metabolism. The proteolysis of Hb is accompanied by the release of free heme, which is cytotoxic for the parasite and is rapidly detoxified and converted into hemozoin (Hz). Therefore, both Hb degradation and heme detoxification are considered to be essential for P. falciparum survival (Goldberg, 2005). The digestion of Hb is a conserved and semiordered process, which principally occurs within the acidified digestive vacuole (DV). After the initial cleavage by aspartic and papain-like cysteine endoproteases, Hb unfolds and becomes accessible to further proteolysis by downstream proteases. In the P. falciparum DV, there are four aspartic proteases (plasmepsins) and two papain-like cysteine proteases (falcipains) capable of hydrolyzing native Hb (Goldberg, 2005; Subramanian et al., 2009). Gene disruption studies of hemoglobinases demonstrated that P. falciparum has developed redundant and overlapping Hb degradation pathways, demonstrating the importance of Hb digestion for the parasite (Liu et al., 2006; Bonilla et al., 2007). However, Hb is a poor source of methionine, cysteine, glutamine, and glutamate; in addition, human Hb contains no isoleucine and P. falciparum blood-stage parasite growth is most effective in culture medium supplemented with these amino acids, especially isoleucine (Liu et al., 2006). These data indicate that P. falciparum parasites are not only dependent on Hb digestion, but also import exogenous amino acids (Liu et al., 2006; Elliott et al., 2008).

Most studies on Hb degradation have been performed using P. falciparum maintained with mature RBCs (normocytes) in vitro. It is unknown whether observations on P. falciparum Hb digestion made in vitro can be directly translated to parasites replicating in vivo or for parasites developing in reticulocytes such as the human parasite P. vivax and P. ovale. For example, mechanisms of resistance to some drugs that interfere with Hb digestion and heme detoxification (e.g., chloroquine) differ between P. vivax and P. falciparum (Baird, 2004; Baird et al., 2012) indicating that there may be differences in their Hb digestion pathways.

To obtain a better insight into Hb digestion in parasites developing in vivo we used a rodent malaria parasite, P. berghei, which preferentially invades reticulocytes. We show a high level of functional redundancy among the predicted hemoglobinases, as 6 of the 8 are dispensable in vivo. Unexpectedly, we were able to create parasite mutants lacking the enzymes known to initiate Hb digestion. These parasites were able to multiply in reticulocytes without Hz formation and were resistant to chloroquine.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

High degree of functional redundancy among Plasmodium hemoglobinases

To determine the essential nature of individual enzymes involved in P. berghei Hb digestion, we performed a loss-of-function analysis on eight predicted P. berghei hemoglobinases. The selection was based on the corresponding P. falciparum orthologous proteases with a characterized role in Hb digestion and/or located in the digestive vacuole (DV; Table S1 and Fig. 1 A). These include the aspartic protease, plasmepsin 4 (PM4), a single enzyme equivalent to the 4 P. falciparum plasmepsins (PM1–4); berghepain-2 (BP2), equivalent to the 2 P. falciparum DV falcipains FP-2 and FP-3; bergheilysin (BLN), the ortholog of P. falciparum falcilysin; dipetidyl peptidase 1 (DPAP1); and 4 aminopeptidases (aminopeptidase P [APP], M1-family alanyl aminopeptidase [AAP], M17-family leucyl aminopeptidase [LAP], and M18-family aspartyl aminopeptidase [DAP]). In addition, we included heme detoxification protein (HDP) and 3 enzymes related to DV proteases with undefined roles in Hb digestion (berghepain 1, the ortholog of P. falciparum falcipain 1 and 2 dipetidyl peptidases, DPAP2 and DPAP3). We successfully generated gene-deletion mutants for pm4, bp1, bp2, dpap1, dpap2, dpap3, app, lap, and dap; however, multiple attempts to disrupt bln, aap, and hdp were unsuccessful (Table S2). We previously reported that disruption of pm4 in P. berghei results in the lack of all aspartic protease activity in the DV (Spaccapelo et al., 2010). Similarly, P. falciparum has been shown to survive without DV PM activity (Bonilla et al., 2007). We were able to generate mutants lacking BP2, whereas P. falciparum blood stages survive without FP2 but not FP3 (Sijwali et al., 2006). We also generated mutants that lack genes encoding DPAP1, APP, and LAP, whereas P. falciparum orthologs have been reported to be refractory to disruption (Table S1; Klemba et al., 2004; Dalal and Klemba, 2007). We were unable to select parasites lacking expression of AAP and BLN, and the P. falciparum orthologous genes aap and bln have also been reported to be resistant to disruption and shown to play additional roles outside DV (Dalal and Klemba, 2007; Ponpuak et al., 2007). We were also unable to select mutants lacking HDP expression, suggesting an essential role for P. berghei blood stages, as has been proposed for P. falciparum HDP (Jani et al., 2008). The successful deletion of 6 of the 8 genes encoding hemoglobinase indicates a high level of redundancy in vivo among these enzymes.

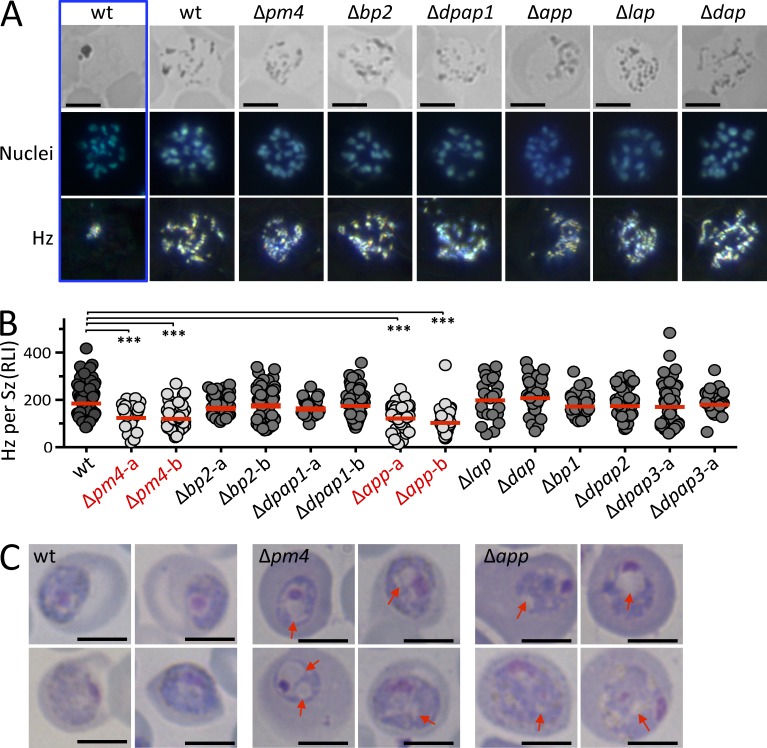

Figure 1.

Δpm4 and Δapp parasites show reduced Hz levels and an aberrant morphology. (A) Reflection contrast polarized light microscopy was used to quantify Hz production inside an iRBC; representative images of Hz in mature Szs are shown. Hz crystals are scattered in Szs and were used for Hz quantification; a single Hz cluster is only observed in fully segmented Szs (blue box); BF, bright field; bars, 5 µm. (B) Relative light intensity (RLI) of polarized light was measured for individual Szs (n > 30; Student’s t test; ***, P < 0.0001). (C) Aberrant morphology of Δpm4 and Δapp Tzs exhibiting reduced Hz production and an accumulation of translucent vesicles (indicated by arrows) in their cytoplasm. Bars, 5 µm. The phenotype was confirmed with two independent mutants.

Mutants lacking PM4, DPAP1, BP1, LAP or APP exhibited a significant reduction in asexual multiplication rates (growth rates) compared with WT parasites, whereas growth rates of the other 4 mutants were not significantly reduced (Table 1). In addition, Δpm4 and Δapp mutants showed a significant reduction in Hz production quantified in mature schizonts (Sz; 8–24 nuclei) using reflection contrast polarized light microscopy (Fig. 1, A and B). Trophozoites (Tz) of Δapp and Δpm4 have an aberrant morphology as visible on Giemsa-stained smears, exhibiting an accumulation of translucent vesicles inside their cytoplasm (Fig. 1 C). The reduced Hz production in Δpm4 and Δapp mutants indicate that P. berghei blood stages can develop into mature Sz despite significantly reduced Hb digestion. The lower growth rate of mutants lacking downstream hemoglobinases DPAP1 and LAP (but with WT Hz levels) indicates that these enzymes are either important in effectively releasing amino acids from Hb peptides or that they have additional functions. Parasites lacking APP unexpectedly also had reduced levels of Hz. However, both APP and LAP are shown to have additional roles, e.g., in cytosolic peptide turnover (Dalal and Klemba, 2007). Although it remains to be investigated, APP may have an indirect effect on the initial steps of Hb digestion, either resulting from its involvement in establishment of the DV or due to feedback mechanisms that inhibit Hb digestion in the absence of APP.

Table 1.

Growth and virulence characteristics of blood stages of gene deletion mutants

| Gene deletion mutant | Day to 0.5–2% parasitemiaa | Multiplication rateb | Hz productionc |

| WTd | 8 (0.2); n = 40 | 10.0 (0.7) | 198.8 (69.8) |

| Δpm4-ae | 9-11; n > 10 | 5.8 (0.5)-7.0 (1.0)f | 129.5 (41.7)f |

| Δpm4-b | 9 (0); n = 2 | 7.7 (0)f | 134.5 (47.6)f |

| Δbp2-a | 8 (0); n = 5 | 10.0 (0) | 177.5 (45.1) |

| Δbp2-b | 8 (0); n = 6 | 10.0 (0) | 188.4 (71.5) |

| Δdpap1-a | 9.5 (0.7); n = 2 | 7.0 (1.0)f | 174.6 (34.0) |

| Δdpap1-b | 9 (0); n = 4 | 7.7 (0)f | 189.2 (62.7) |

| Δapp-a | 12 (0); n = 1 | 4.6 (0)f | 131.8 (50.5)f |

| Δapp-b | 12 (0); n = 4 | 4.6 (0)f | 111.4 (49.7)f |

| Δdap | 8 (0); n = 3 | 10.0 (0) | 223.8 (65.7) |

| Δlap | 15.5 (0.7); n = 2 | 3.3 (0.2)f | 213.6 (78.7) |

| Δbp1-a | 9.7 (0.6); n = 3 | 6.8 (0.8)f | 186.2 (49.2) |

| Δbp1-b | 9 (0); n = 1 | 7.7 (0)f | n.d. |

| Δdpap2 | 8.3 (0.4); n = 4 | 9.4 (1.0) | 187.8 (64.6) |

| Δdpap3-a | 8.3 (0.6); n = 3 | 9.2 (1.3) | 184.5 (86.3) |

| Δdpap3-b | 8 (0); n = 5 | 10.0 (0) | 193.3 (46.8) |

| Δpm4Δbp2-a | 12, 16, 20; n = 3 | 3.4 (1.1)f | 27.2 (36.5)f |

| Δpm4Δbp2-b | 21, 24; n = 2 | 2.3 (0.1)f | 46.1 (51.2)f |

n.d., not determined.

The day on which the parasitemia reaches 2—5% in mice infected with a single parasite in cloning assays. The mean of one cloning experiment and standard deviation are shown (n = the number of mice). For the Δpm4Δbp2 mutants, the days for individual clones are shown.

The multiplication rate (mean and SD) of asexual blood stages per 24 h, calculated based on the “day to 0.5–2% parasitemia” in the cloning assay.

Relative light intensity (mean and SD) of Hz crystals in individual Szs, determined by polarized light microscopy. See Fig.1.

WT, wild type P. berghei ANKA reference lines (cl15cy1, 676m1cl1, and 1037cl1). Data from >10 independent experiments.

pm4 gene-deletion mutants generated by Spaccapelo et al. (2010).

P < 0.0001; Student’s t test.

Parasites lacking both PM4 and BP2 are restricted to reticulocytes and produce smaller Szs with less merozoites

Because in P. berghei PM4 is the only DV aspartic protease and BP2 is the single syntenic ortholog of the two P. falciparum DV cysteine endoproteases (FP-2 and FP-3), the absence of these enzymes is expected to result in the failure to proteolyse native Hb. Unexpectedly, we were able to generate two independent mutants lacking expression of both PM4 and BP2 (Δpm4Δbp2; Table S2). Blood stages of Δpm4Δbp2 have a severely reduced multiplication rate (2.2–4.6 compared with WT rates of 10; Table 1). After an initial slow rise of parasite numbers in Δpm4Δbp2-infected mice, parasitemia can reach levels of up to 50% when mice became anemic and the RBCs were principally reticulocytes (unpublished data). At high parasitemias, mature Sz were present in the blood, most of which contained 8–12 merozoites (Fig. 2 A). Even though ring forms of Δpm4Δbp2 were observed in both mature RBCs and reticulocytes, mature Tz and Sz were exclusively found in reticulocytes (unpublished data), indicating that Δpm4Δbp2 parasites, while retaining their ability to invade all RBCs, are unable to develop in normocytes. This may be related to greater abundance/diversity of amino acids and proteins present in reticulocytes (Allen, 1960), or due to other physical characteristics of reticulocytes, for example, their larger size and reduced Hb content may provide more space for growth in the absence of Hb digestion.

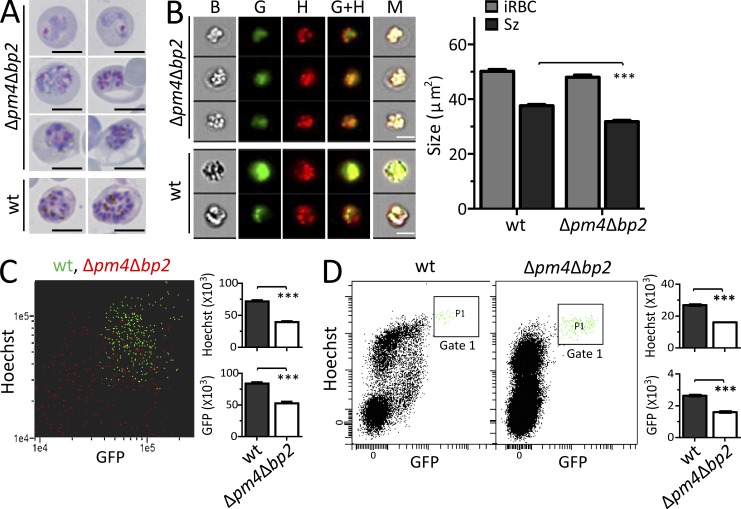

Figure 2.

Szs of mutants lacking PM4 and BP2 expression are smaller in size and produce fewer merozoites. (A) Representative Giemsa-stained images showing the difference in size and merozoites production of Δpm4Δbp2 iRBCs relative to WT. Bars, 5 µm. (B) Images of Hoechst stained mature WT and Δpm4Δbp2 Szs expressing GFP under Sz-specific ama1 promoter in their cytoplasm (right) and their size measurement by ImageStream flow cytometry (left). Bars, 5 µm. The size of individual iRBC was determined from bright field images (B) and the size of Sz was measured from the combined GFP (G) and Hoechst (H) images (i.e., G+H). M, merged images (n > 250; ***, P < 0.0001; Student’s t test). (C) The dot plot (left) generated from ImageStream flow cytometry shows the GFP- and Hoechst-fluorescence of individual WT- (green) and Δpm4Δbp2- (red) Sz, and the GFP expression and DNA content were quantified (right). (D) The GFP and DNA content of mature Szs were measured by standard flow cytometry; mature Szs were selected in Gate 1 (left) and the quantification shown as bar graphs (right). All data are representative of two independent experiments (bar graphs show mean fluorescence intensity with SEM; ***, P < 0.0001; Student’s t test).

Analysis of Giemsa-stained images revealed Δpm4Δbp2-Sz to be small, occupying only 25–65% of the RBCs, compared with 60–90% of WT Sz (n > 30; Fig. 2 A). This size reduction was confirmed by ImageStream flow cytometry on live WT and Δpm4Δbp2 Szs expressing GFP under the control of the Sz-specific ama-1 promoter (Fig. 2 B). Analysis of Giemsa-stained parasites indicated that Δpm4Δbp2 Szs had fewer merozoites (Fig. 2 A). Measuring GFP and Hoechst fluorescence intensity by ImageStream and standard flow cytometry confirmed that mature Δpm4Δbp2-Sz have 40% reduction in both total DNA and (ama1-based) GFP expression levels compared with WT Sz, indicating a significant reduction in the total number of merozoites per Sz (Fig. 2, C and D). Combined, these observations demonstrate that Δpm4Δbp parasites produce smaller Sz with less daughter merozoites than WT Sz.

Parasites lacking both PM4 and BP2 can form Szs in the absence of detectable Hz

Most Δpm4Δbp2 Tzs have an amoeboid-like appearance with translucent vesicles inside their cytoplasm, and their Tzs and Szs have little or no visible Hz (Fig. 2 A). Ultrastructural analyses confirmed this, showing that Δpm4Δbp2 Tzs contained a higher number of cytostomes or endocytic vesicles filled with material that had a structural appearance similar to RBC cytoplasm (Fig. 3 A). This indicates that the absence of PM4 and BP2 does not affect the uptake of Hb from the RBC cytoplasm. Electron microscopic images revealed that 37% of the Tzs contained dark-stained (electron-dense) vesicles that are completely absent from WT parasites (Fig. 3 A). These vesicles are very similar to those that have been described in P. falciparum Tz when Hb trafficking or digestion is blocked by inhibitors, and it has been proposed that these vesicles are cytostome derived and contain concentrated undigested and/or denatured Hb (Fitch et al., 2003; Vaid et al., 2010). In addition, although WT Tz contained large numbers of Hz crystals, >40% of Δpm4Δbp2 Tz had no visible Hz crystals (Fig. 3 A), reflecting our observations with Giemsa-stained images of Tz and Sz (Fig. 2 A). Next, we used reflection contrast polarized light-microscopy to determine the amount of Hz in maturing Δpm4Δbp2-Sz and WT-Sz. The relative light intensity (RLI) values of Δpm4Δbp2-Sz at all stages of maturation were strongly reduced (78–87% reduction compared with WT Sz; Fig. 3 B and Table 1), and whereas all WT Sz had Hz, a large percentage (35–48%) of Δpm4Δbp2-Sz had no detectable Hz (Fig. 3 B), having RLI values the same as uninfected RBCs. The severe reduction in Hz production was also reflected in vastly reduced Hz deposition in organs of Δpm4Δbp2-infected mice compared with WT- and even Δpm4-infected mice (Fig. 3 C).

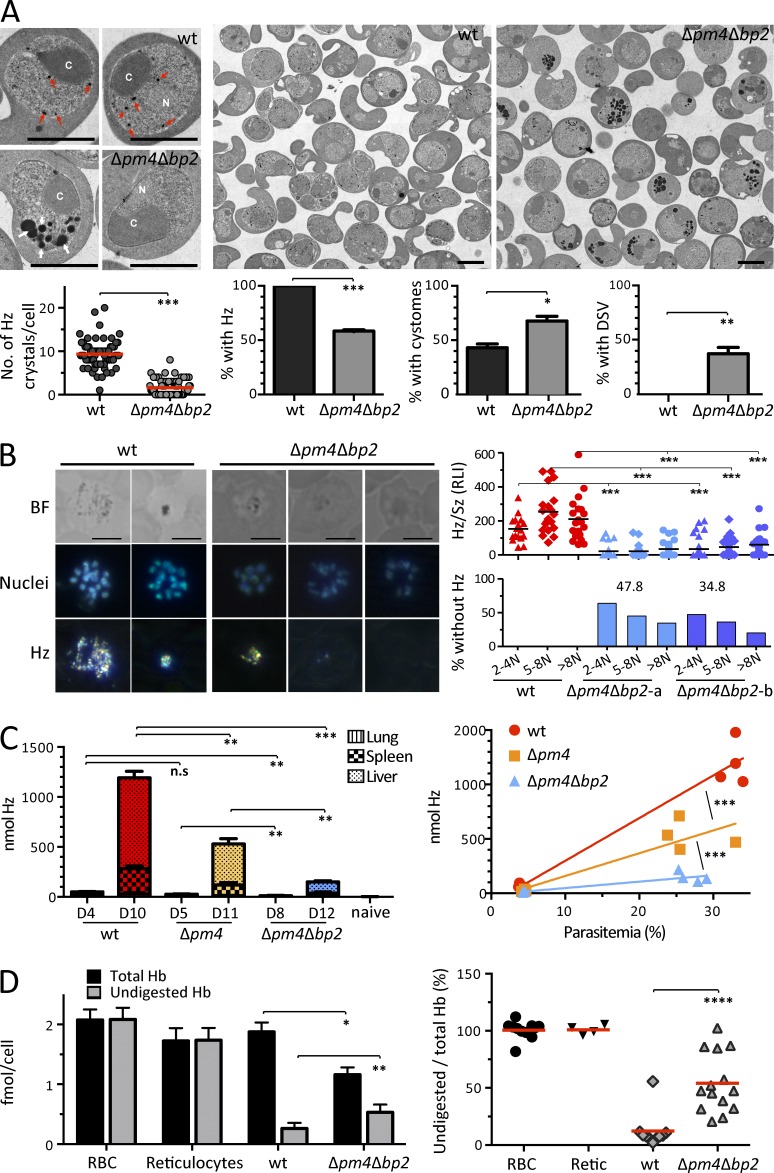

Figure 3.

Δpm4Δbp2 mutant parasites can develop into mature Szs with reduced Hb digestion and little or no detectable Hz. (A) Electron microscopy images of Δpm4Δbp2 and WT-Tzs were used to identify and calculate the number of Hz crystals (red arrows), cytostomes (C), and dark-staining vesicles (DSV, white arrows) in WT and Δpm4Δbp2 parasites. Data were obtained from 3 EM image fields (n > 60; ***, P < 0.0005; Student’s t test). N, nucleus. Bars, 5 µm. (B) Reflection contrast polarized light microscopy was used to quantify Hz production in Δpm4Δbp2 and WT Sz. Bright field (BF) and polarized light microscopy images showing Hz in individual representative Sz (left). Relative light intensity (RLI) of Hz crystals was measured in individual WT or Δpm4Δbp2 Sz containing either 2–4, 5–8, or >8 nuclei (N; n > 20; ***, P < 0.0005; Student’s t test; right). Bars, 5 µm. (C) Hz deposition in different organs of BALB/c mice infected with WT or Δpm4Δbp2-parasites at different days after infection was quantified. The deposition of Hz in different organs at different days (left; data presented as mean with SEM; n = 4) and the relationship between total Hz levels (nmol) quantified from all organs and peripheral parasitemias (right); **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0005 (Student’s t test). (D) Quantification of total Hb and undigested Hb, using heme-dependent, luminol-enhanced luminescence, in WT and Δpm4Δbp2 Sz iRBCs; Hb and Hz levels in mature RBC and reticulocytes (left; data presented as mean with SEM) and the percentage of undigested Hb in these cells (right) are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ****, P < 0.001; Student’s t test, n > 3. Data were pooled from three independent experiments.

We further quantified the amount of Hz and undigested Hb in equal numbers of FACS-purified Sz using heme-dependent luminol-enhanced luminescence analysis (Schwarzer et al., 1994). The Hb that remained undigested in Δpm4Δbp2-Sz iRBCs was twice the amount of that in WT-Sz iRBCs (Fig. 3 D); however, the total heme content in Δpm4Δbp2-Sz iRBCs was 40% lower than WT-Sz iRBCs. On average, 54% (between 20–100%) of Hb remains undigested in Δpm4Δbp2-Sz iRBCs, compared with 12% of WT-Sz iRBCs (Fig. 3 D). Combined, the increased number of cytostome inclusions, presence of unusual electron-dense vesicles and severely reduced and often absent Hz crystals indicate that Hb digestion is severely impaired in Δpm4Δbp2 and this is further supported by the high levels of undigested Hb present in RBCs infected with Δpm4Δbp2 Sz compared with WT-Sz. However, some Hz is still present in a proportion of Δpm4Δbp2 parasites indicating that some heme is released from Hb in the absence of PM4 and BP2. Whether this is the result of a compensatory enzymatic process or a nonspecific disassembly of the Hb tetramer that may occur when Hb accumulates in cytostomes or in the acidified dark-staining vesicles (Fitch et al., 2003) is unknown and requires further investigation.

In P. falciparum the PMs and FPs overlap in function and there is extensive functional redundancy within and between these two protease classes (Bonilla et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2006). Our observations on Hz production in the single gene-deletion mutants Δpm4 and Δbp2 indicate that also in P. berghei aspartyl and cysteine endopeptidases overlap in their ability to hydrolyze Hb. Interestingly, the Δbp2 mutant has a normal growth rate and produces WT levels of Hz, whereas Δpm4 parasites have a reduced growth and Hz production. These observations demonstrate that although PM4 is able to fully compensate for the function of BP2, BP2 can only partly compensate for the loss of PM4.

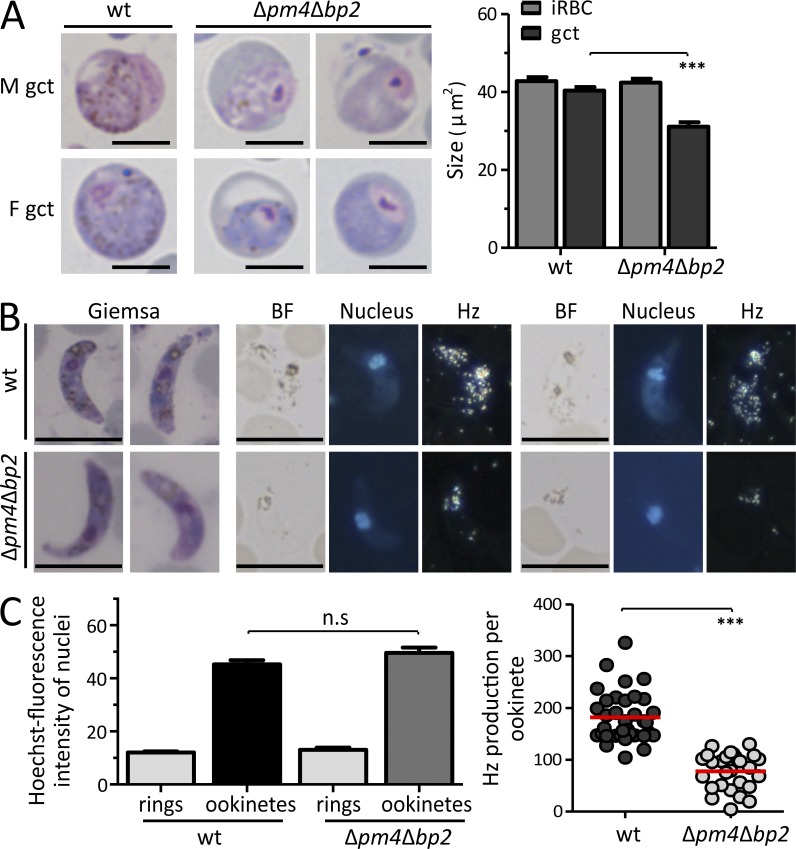

Gametocytes of parasite lacking both PM4 and BP2 are fertile despite their smaller size and reduced Hz levels

In mice infected with Δpm4Δbp2 parasites, male and female gametocytes were readily detected. Similar to Sz, they were 23% smaller than WT gametocytes, and their cytoplasm had strongly reduced or no Hz crystals (Fig. 4 A). Most Δpm4Δbp2 male gametocytes produced motile gametes (79.3 ± 4.6%), which are able to fertilize female gametes and produce ookinetes; these undergo meiosis and become tetraploid (Fig. 4, B and C). The conversion rates of Δpm4Δbp2 female gametes into ookinetes were comparable to those of WT parasites (60.0 ± 6.1%; Fig. 4 C). Analysis of Hz levels in WT and Δpm4Δbp2 ookinetes revealed that they also had reduced Hz-levels (57%; Fig. 4 C). These observations demonstrate that both asexual and sexual blood-stages can complete development despite the severely impaired Hb digestion.

Figure 4.

Gametocytes of Δpm4Δbp2 are fertile despite their smaller size and reduced Hz production. (A) Representative Giemsa-stained images of WT and Δpm4Δbp2 gametocytes (left; bars, 5 µm) and the size quantification on these images (right; n > 30; ***, P < 0.0001; Student’s t test). (B) Giemsa-stained images and polarized light microscopy images of ookinetes. BF, bright-field; Nuclei (blue) stained with Hoechst. Bars, 5 µm. (C) Hoechst fluorescence intensity (DNA content) of WT and Δpm4Δbp2 ookinetes, relative to haploid ring-form stages, was quantified (left; n > 25; n.s, not significant; Student’s t test) indicating that both WT and Δpm4Δbp2 ookinetes are tetraploid. Relative light intensity (RLI) of polarized light (Hz production) measurements of WT and Δpm4Δbp2 ookinetes (right; n > 25; ***, P < 0.0001; Student’s t test).

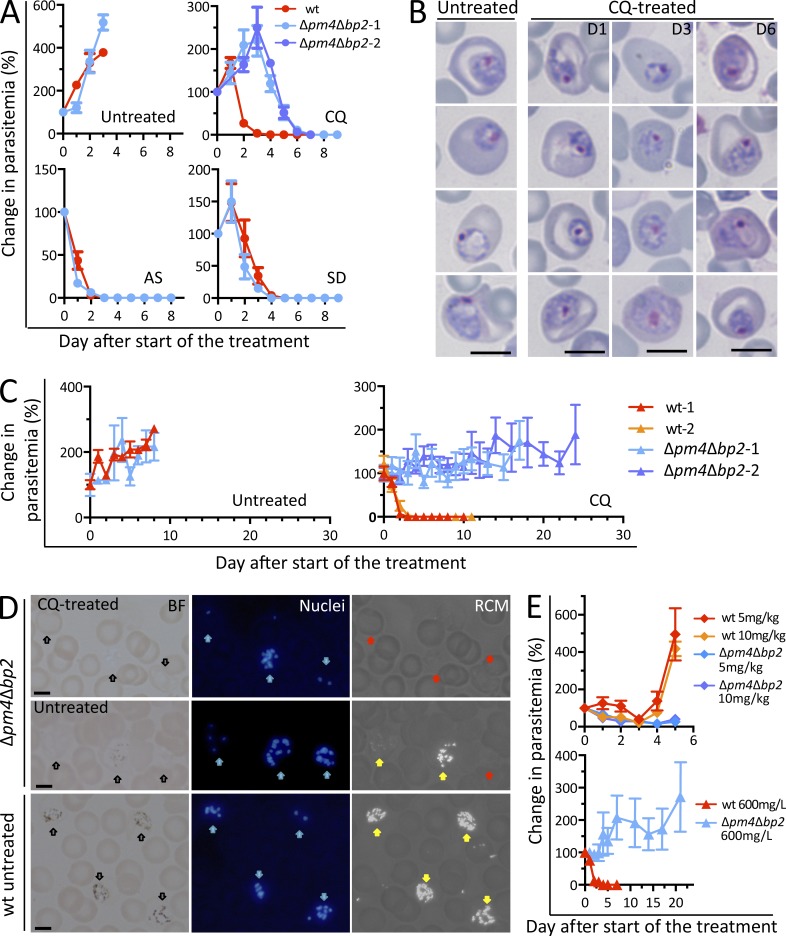

Parasites lacking both PM4 and BP2 are resistant to chloroquine but retain their sensitivity to artesunate

We tested the sensitivity of the Δpm4Δbp2 parasites to artesunate (AS) and chloroquine (CQ); their mode of action is believed to depend on Hb digestion/Hz formation (Egan et al., 2004; Klonis et al., 2011). As a control we used sulfadiazine (SD), an inhibitor of folic acid synthesis (Kinnamon et al., 1976). AS and SD treatment of WT- and Δpm4Δbp2-infected BALB/c mice resulted in rapid clearance of parasites from bloodstream in 3–4 and 4–5 d after start of AS (50 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) and SD (35 mg/liter in drinking water) treatment, respectively (Fig. 5 A). Similarly, BALB/c mice infected with WT parasites rapidly cleared their infection after CQ (288 mg/liter in drinking water) treatment (3–4 d). In contrast, mice infected with pm4bp2 parasites, first exhibited an increase in parasitemia for 3 d, followed by a slow decline (Fig. 5 A). Parasites with normal morphology were present 6 d after start of CQ treatment (Fig. 5 B). Untreated BALB/c mice also resolved a Δpm4Δbp2 infection 3–4 wk after infection, indicating that host immunity may contribute to the decline of parasitemia in CQ-treated mice. We therefore performed infections and CQ treatment in Rag2−/−γc−/− mice (deficient in B, T, and NK cells). Whereas CQ-treated, WT-infected mice cleared a 2–5% WT infection within 3 d, in Δpm4Δbp2-infected mice parasites persisted for >20 d of CQ-treatment (Fig. 5 C), during which only Hz-negative Δpm4Δbp2 parasites were observed in circulation (Fig. 5 D). To examine whether Δpm4Δbp2 parasite resistance to CQ is lost at higher concentrations of CQ and conversely if resistance to AS is observed at lower concentrations of AS, we performed drug sensitivity assays using 5 and 10 mg/kg AS (in BALB/c mice) or with 600 mg/liter CQ (in Rag2−/−γc−/− mice). These experiments revealed that, at lower AS doses, drug sensitivity does not significantly differ between Δpm4Δbp2 and WT parasites, and that Δpm4Δbp2 parasites are resistant to CQ even at high doses (Fig. 5 E).

Figure 5.

Δpm4Δbp2 parasites are resistant to chloroquine but sensitive to artesunate. (A) Changes in parasitemia of BALB/c mice (n = 5) infected with WT or Δpm4Δbp2 parasites after treatment with chloroquine (CQ; 288mg/liter in drinking water; 2 experiments), artesunate (AS; 50 mg/kg body weight i.p), or sulfadiazine (SD; 35 mg/liter in drinking water). Data presented as mean with SEM. (B) Representative Giemsa-stained images of pm4Δbp2-Tzs in blood of BALB/c mice treated with CQ treatment at different days (D1, 3, 6) after start of CQ treatment. Bars, 5 µm. (C) Changes in parasitemia of Rag2−/−γc−/− (n = 6) mice infected with WT or Δpm4Δbp2 parasites either without treatment (left) or after prolonged CQ treatment (right; 288 mg/l in drinking water; 2 experiments). (D) Reflection contrast polarized light microscopy images (RCM) showing the absence of Hz crystals in Δpm4Δbp2 parasites that survived CQ treatment for >20 d in Rag2−/−γc−/− mice; iRBC with no Hz formation are indicated by red arrows. In untreated mice, two populations of Δpm4Δbp2 parasites are present, parasites with no Hz (red arrow), and parasites with Hz crystals (yellow arrows). WT parasites in untreated mice show large amounts of Hz (yellow arrows). Black arrows indicate iRBC in bright field (BF) images. Nuclei of parasites (blue) were stained with Hoechst (blue arrows). Bars, 5 µm. (E) Changes in parasitemia of BALB/c mice (top, n = 5) or Rag2−/−γc−/− mice (bottom, n = 5) infected with Δpm4Δbp2 and WT parasites exposed to either 5 or 10 mg/kg of AS in or to 600 mg/l CQ in drinking water. Data presented as mean values of changes (%) in parasitemia with SEM.

Our observations on the ability of Plasmodium parasites to develop without detectable Hz formation that are resistant to CQ indicate a novel mechanism of resistance against drugs that target Hb proteolysis. Interestingly, previous studies on CQ-resistant P. berghei lines revealed that parasites are more restricted to development in reticulocytes and produced less Hz (Platel et al., 1999). It has been proposed that CQ-resistance of parasites with reduced Hz is due to detoxification of hemin by elevated levels of glutathione in parasites inside reticulocytes, thus precluding heme-polymerization and preventing CQ activity (Platel et al., 1999; Fidock and DeSilva, 2012). However, our observations may provide a more direct explanation for CQ-resistance and reduced Hz production in these parasites, namely that these parasites, like the Δpm4Δbp2, digest less Hb in reticulocytes.

Our observations may have particular relevance for the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium vivax, which is also reticulocyte-restricted. P. vivax CQ resistance appears to be different from P. falciparum (Suwanarusk et al., 2007; Baird et al., 2012), and no clear association has been found with mutations in the same genes that typify P. falciparum CQ resistance (pfcrt or pfmdr1). In addition, DV formation in P. vivax appears to resemble more DV formation in P. berghei than in P. falciparum. Tzs of P. falciparum have a large central DV, as Hb-containing cytostomes merge rapidly and Hz formation occurs principally in this single DV. In contrast, P. berghei has many small Hb-containing vesicles, in which Hb digestion/Hz formation occurs, resulting in scattered Hz granules throughout the cytoplasm of the parasite, these clusters coalesce when schizogony starts (Slomianny et al., 1985). It has been suggested that the uptake of Hb from reticulocytes by the process of micropinocytosis results in multiple small vesicles containing Hb and Hz in both P. berghei and P. vivax (Jeffers, 2010). Moreover P. vivax, like P. berghei, has only 1 DV plasmepsin (PM4) in contrast to P. falciparum which encodes 4 DV plasmepsins (Table S1). While P. vivax has 3 DV vivapains, 2 of them, VX2 and 3, are syntenic orthologs of FP-2 and 3 the other, VX4, is nonsyntenic with the FPs but shows greater sequence similarity to BP2 (Na et al., 2010; Table S1). These observations indicate that mechanisms of Hb uptake and digestion in P. vivax more closely resembles P. berghei than P. falciparum and future research is required to see if this also translates into similar mechanisms to resistance to drugs that exclusively target Hb digestion pathways.

Although Δpm4Δbp2 parasites are resistance to CQ, they retain sensitivity to AS. Although the precise mode of action of artemisinin and related derivatives remains contentious, it is believed that their activity results from activation by reduced heme iron in the DV (Eastman and Fidock, 2009). Our results suggest AS activity is not affected by reduced Hb digestion or absence of Hz formation. Alternatively AS activation in Δpm4Δbp2 parasites in reticulocytes may derive from a labile pool of heme that exists in reticulocytes for Hb synthesis. P. vivax resistance to artemisinins has not been reported; however, most of the artemisinin-based combination therapies have proven efficacy against chloroquine-resistant strains of P. vivax (Price et al., 2014).

We show that, very much counter to expectation, Hb digestion and Hz formation appears not to be essential to parasite survival when parasites develop in reticulocytes. Indeed, our findings support the notion that Plasmodium parasites retain multiple modes of development and survival during blood stage development, which has important implications for antimalarial drug design, in particular drugs that target Hb digestion and Hz formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and parasites.

Female C57BL/6, BALB/c, Swiss OF1 mice (6–8 wk old; Charles River) and female Rag2−/−γc−/− mice (6–8 wk old, bred in MRC NIMR) were used. All animal experiments performed at the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) were approved by the Animal Experiments Committee of the LUMC (DEC 10099; 12042; 12120). All animal experiments performed at the University of Perugia were approved by Ministry of Health under the guidelines D.L. 116/92). All animal experiments performed in MRC NIMR were performed after review and approval by the MRC National Institute for Medical Research Ethical Review Panel in strict accordance to current UK Home Office regulations, and conducted under the authority of UK Home Office Project License PPL 80/2358. The Dutch, Italian, and British Experiments on Animal Act were established under European guidelines (EU directive no. 86/609/EEC regarding the Protection of Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes).

Two reference P. berghei ANKA parasite lines were used: line cl15cy1 (WT) and reporter line 1037cl1 (WT-GFP-Lucschiz; mutant RMgm-32). This reporter line contains the fusion gene gfp-luc gene under control of the Sz-specific ama1 promoter integrated into the silent 230p gene locus (PBANKA_030600) and does not contain a drug-selectable marker (Spaccapelo et al., 2010).

Generation of P. berghei mutants.

DNA constructs used to disrupt genes were based on the standard plasmids (pL0001 [MRA-770], pLTgDFHR, and pL0035; [MRA-850]) and by modified PCR methods based on pL0040 and pL0048 (Lin et al., 2011). Targeting sequences for homologous recombination were PCR amplified from P. berghei ANKA (cl15cy1) genomic DNA using primers specific for the 5′ or 3′ end of each gene using primer sets of P1/P2, P3/P4, respectively (see Table S3 for the primer sequences).

The DNA construct targeting bp1 was provided by P. Sinnis (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Transfection, selection, cloning, and genotyping of transformed parasites was performed using standard genetic modification technologies for P. berghei (Janse et al., 2006). To generate Δpm4Δbp2 mutant, hdhfr::yfcu selectable marker was removed by negative selection (Braks et al., 2006) from Δbp2-b (based on pL0035) and pm4 gene was subsequently targeted in Δbp2-b-sm line. Table S2 provides details of all gene deletion experiments, such as experiment number, targeting construct, parental line for transfection, and RMgmDB IDs (Rodent Malaria Genetically Modified Parasites Database). Details for targeting construct generation (maps and sequences) and genotyping results can be found in RMgmDB and Table S4 includes primers used for genotyping including diagnostic PCR, Southern analyses of chromosomes separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, Northern PCR, and RT-PCR.

In vivo asexual multiplication (growth) rates.

The multiplication (growth) rate of asexual blood-stages in mice was determined during cloning of the gene-deletion mutants as described before (Spaccapelo et al., 2010) and was calculated as follows: the percentage of infected erythrocytes (parasitemia) in Swiss OF1 mice injected with a single parasite was determined by counting Giemsa-stained blood films when parasitemias reach 0.5–2%. The mean asexual multiplication rate per 24 h was then calculated assuming a total of 1.2 × 1010 erythrocytes per mouse (2 ml of blood). The percentage of infected erythrocytes in mice infected with reference lines of the P. berghei ANKA strain consistently ranged between 0.5–2% at day 8 after infection, resulting in a mean multiplication rate of 10 per 24 h.

Gametocyte and ookinete production.

Gametocyte production is defined as the percentage of ring forms developing into mature gametocytes during synchronized infections (Janse and Waters, 1995). Male gamete production (exflagellation) and ookinete production was determined in standard in vitro fertilization and ookinete maturation assays (Janse and Waters, 1995); ookinete production is defined as the percentage of female gametes that develop into mature ookinetes under standardized in vitro culture conditions. Female gamete and mature ookinete numbers were determined on Giemsa-stained blood smears made 16–18 h after activation. Hz level of ookinetes were quantified.

Sz and gametocyte size measurements.

For the Giemsa-stained smears, pictures were taken using a Leica microscope from randomly chosen fields of 300–400 RBCs, and all iRBCs were measured in these fields. The sizes of iRBCs and the parasites were measured by ImageJ by gating on the areas of parasites and iRBC. For ImageStream flow cytometry analysis, iRBCs containing Szs of WT-GFP-Lucschiz and Δpm4Δbp2 parasites were collected from infected BALB/c mice with a high parasitemia (10–30%) and enriched by Nycodenz density centrifugation (Janse et al., 2006). Purified parasites were then collected in complete RPMI-1640 culture medium and stained with Hoechst-33258 (2 µmol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature. Cultured, mature Szs of WT P. berghei ANKA (cl15cy1) were used as unstained control; Hoechst stained cl15cy1 (Hoechst only) and nonstained WT-GFP-Lucschiz (GFP only) were used as single-color controls. The analyses were performed using an Amnis ImageStream X imaging cytometer (Amnis Corp.) and images were analyzed using the IDEAS image analysis software.

Hz and Hb quantification.

Hz was quantified in Szs using different methods. Hz was quantified by measuring the relative light intensity (RLI) of Hz crystals in Szs and ookinetes by reflection contrast polarized light microscopy. Szs were either collected from overnight in vitro blood stage cultures or directly from tail blood when Szs were present in the peripheral circulation. Blood smears were made from cultured parasites or from tail blood and stained with Hoechst-33342 (2 µmol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min. Szs (8–24 nuclei) with scattered Hz were selected and pictures were taken with a LeicaDM/RB microscope (Leica) which was adapted for reflection contrast polarized light microscopy (Cornelese-ten Velde et al., 1988). The RLI of Hz crystals in the Szs was measured using ImageJ software (NIH).

In addition, Hb and Hz from WT and Δpm4Δbp2 Sz-iRBC were quantified by measuring the heme-dependent luminol-enhanced luminescence (Schwarzer et al., 1994). For these experiments, 104 purified Szs were collected by flow sorting from infected blood of BALB/c mice with a high parasitemia (10–30%) and stained with Hoechst-33258 (2 µmol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in the dark for 1 h. Subsequently, Szs were selected and sorted with a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD; speed 10,000 events/s). Mature Szs were selected by gating on the GFP+ population of cells with a DNA content of Szs (Hoechst fluorescence intensity 8–24 N; Fig. 2 D, gate 1). Purified Szs were washed with PBS and concentrated in 10 µl of PBS and kept at −80°C until further analysis. Szs were analyzed for their Hb and Hz content. Hb-bound heme and alkali-solubilized Hz-heme were assayed by luminol-enhanced luminescence in the untreated or strong alkali-treated lysates prepared as detailed previously (Schwarzer et al., 1994).

To quantify Hz deposition in organs of infected mice, groups of 8 BALB/c mice were i.p. infected with 105 WT, Δpm4, or Δpm4Δbp2 parasites. At different parasitemias, mice were sacrificed and systemically perfused with 20 ml PBS to remove circulating iRBC from the organs. Livers, spleens, and lungs were removed, weighed and stored at −80°C until further analysis. The Hz extraction from these organs and quantification was performed using an optimized method for Hz quantification in tissues as described (Deroost et al., 2012).

Electron microscopy analysis.

Infected blood was collected from WT or Δpm4Δbp2 parasite infected BALB/c mice by heart puncture and enriched by Nycodenz centrifugation (Janse et al., 2006). IRBC (107–108) were collected and fixed overnight in 2 ml of 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate. After centrifugation, the pellet was rinsed twice with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate. After rinsing, samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series up to 100% and embedded in epon. 110-nm sections were cut with a microtome and transferred onto standard grids and post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) data were collected on a FEI Tecnai microscope at 120 kV with a FEI Eagle CCD camera. Virtual slides (Faas et al., 2012) consisting of 759 and 729 unbinned 4kx4k images were collected for the WT and Δpm4Δbp2 sample, respectively. The magnification at the detector plane was 12930: the pixel size 1.2 nm square. The resulting slides cover an area of 109 × 105 µm2 and 105 × 105 µm2 for the respective samples. The virtual slides were analyzed by Aperio ImageScope software (Aperion). All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism.

Drug sensitivity assays.

Groups of 5–6 BALB/c or Rag2−/−γc−/− mice were i.p. infected with either 104 WT or 105 Δpm4Δbp2-parasites. At a peripheral parasitemia of 2–5%, mice were treated with artesunate (AS; Pharbaco; 60 mg powder [a gift from Dafra Pharma International, Turnhout, Belgium], chloroquine [CQ; Sigma-Aldrich], or sulfadiazine [SD; Sigma-Aldrich]) and parasitemia was monitored daily by counting Giemsa-stained blood films of tail blood. AS treatment was performed by i.p. injection of 6.25, 1.25, or 0.625 mg/ml in 5% NaHCO3 as a single dose for 4 consecutive days (50, 10, or 5 mg/kg body weight). SD was provided at a concentration of 35 mg/liter in drinking water for 7 d, and CQ was provided at a concentration of 288 or 600 mg/liter with 15 g/liter glucose in the drinking water for a period of 7 d in BALB/c or up to 25 d in Rag2−/−γc−/− mice. The parasitemia was monitored every 1–2 d by Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. All infected mice were sacrificed when the parasitemia reached 50%.

Graphs and statistical analyses.

All graphs and statistical analyses were made in GraphPad Prism, all error bars indicate SEM and all p-values were derived from unpaired Student’s t tests.

Supplemental material.

Table S1 shows genes targeted in this study. Table S2 shows details of transfection experiments aiming at deletion of P. berghei genes encoding hemoglobinases. Table S3 shows gene deletion constructs and primers. Table S4 shows primers for genotyping gene-deletion mutants. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20141731/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Photini Sinnis for providing us with a P. berghei bp1 gene deletion construct, J.J. Onderwater for electron microscopy sample preparation, and Guido de Roo and Sabrina Veld for assistance with flow cytometry experiments.

J.-w. Lin was supported by the China Scholarship Council-Leiden University Joint Program and C.J. Janse by a grant of the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 242095. K. Deroost was supported by a PhD grant of the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT), and P.E. Van den Steen was supported by a grant of the “Geconcerteerde OnderzoeksActies” (GOA 2013/014) of the Research Fund of the KU Leuven, and by the Fund for Scientific Research (F.W.O.-Vlaanderen). J. Langhorne is supported by the MRC, UK (U117584248).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- AS

- artesunate

- BP

- berghepain

- CQ

- chloroquine

- DV

- digestive vacuole

- FP

- falcipain

- Hb

- hemoglobin

- Hz

- hemozoin

- iRBC

- infected red blood cell

- PM

- plasmepsin

- RBC

- red blood cell

- RLI

- relative light intensity

- SD

- sulfadiazine

- Sz

- schizont

- Tz

- trophozoites

References

- Allen D.W. 1960. Amino acid accumulation by human reticulocytes. Blood. 16:1564–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird J.K. 2004. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium vivax. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4075–4083. 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4075-4083.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird K.J., Maguire J.D., and Price R.N.. 2012. Diagnosis and treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Adv. Parasitol. 80:203–270. 10.1016/B978-0-12-397900-1.00004-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla J.A., Bonilla T.D., Yowell C.A., Fujioka H., and Dame J.B.. 2007. Critical roles for the digestive vacuole plasmepsins of Plasmodium falciparum in vacuolar function. Mol. Microbiol. 65:64–75. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braks J.A., Franke-Fayard B., Kroeze H., Janse C.J., and Waters A.P.. 2006. Development and application of a positive-negative selectable marker system for use in reverse genetics in Plasmodium. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e39 10.1093/nar/gnj033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelese-ten Velde I., Bonnet J., Tanke H.J., and Ploem J.S.. 1988. Reflection contrast microscopy. Visualization of (peroxidase-generated) diaminobenzidine polymer products and its underlying optical phenomena. Histochemistry. 89:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S., and Klemba M.. 2007. Roles for two aminopeptidases in vacuolar hemoglobin catabolism in Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 282:35978–35987. 10.1074/jbc.M703643200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroost K., Lays N., Noppen S., Martens E., Opdenakker G., and Van den Steen P.E.. 2012. Improved methods for haemozoin quantification in tissues yield organ-and parasite-specific information in malaria-infected mice. Malar. J. 11:166 10.1186/1475-2875-11-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R.T., and Fidock D.A.. 2009. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:864–874. 10.1038/nrmicro2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan T.J., Koch K.R., Swan P.L., Clarkson C., Van Schalkwyk D.A., and Smith P.J.. 2004. In vitro antimalarial activity of a series of cationic 2,2′-bipyridyl- and 1,10-phenanthrolineplatinum(II) benzoylthiourea complexes. J. Med. Chem. 47:2926–2934. 10.1021/jm031132g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D.A., McIntosh M.T., Hosgood H.D. III, Chen S., Zhang G., Baevova P., and Joiner K.A.. 2008. Four distinct pathways of hemoglobin uptake in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:2463–2468. 10.1073/pnas.0711067105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faas F.G., Avramut M.C., van den Berg B.M., Mommaas A.M., Koster A.J., and Ravelli R.B.. 2012. Virtual nanoscopy: generation of ultra-large high resolution electron microscopy maps. J. Cell Biol. 198:457–469. 10.1083/jcb.201201140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidock M., and DeSilva B.. 2012. Bioanalysis of biomarkers for drug development. Bioanalysis. 4:2425–2426. 10.4155/bio.12.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C.D., Cai G.Z., Chen Y.F., and Ryerse J.S.. 2003. Relationship of chloroquine-induced redistribution of a neutral aminopeptidase to hemoglobin accumulation in malaria parasites. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 410:296–306. 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00688-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D.E. 2005. Hemoglobin degradation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 295:275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani D., Nagarkatti R., Beatty W., Angel R., Slebodnick C., Andersen J., Kumar S., and Rathore D.. 2008. HDP-a novel heme detoxification protein from the malaria parasite. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000053 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse C.J., and Waters A.P.. 1995. Plasmodium berghei: the application of cultivation and purification techniques to molecular studies of malaria parasites. Parasitol. Today (Regul. Ed.). 11:138–143. 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80133-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse C.J., Ramesar J., and Waters A.P.. 2006. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat. Protoc. 1:346–356. 10.1038/nprot.2006.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers V. 2010. Shedding light on Plasmodium knowlesi food vacuoles. A thesis submitted to Combined Faculties for the Natural Sciences and for Mathematics of the Ruperto-Carola University of Heidelberg for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnamon K.E., Ager A.L., and Orchard R.W.. 1976. Plasmodium berghei: combining folic acid antagonists for potentiation against malaria infections in mice. Exp. Parasitol. 40:95–102. 10.1016/0014-4894(76)90070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemba M., Gluzman I., and Goldberg D.E.. 2004. A Plasmodium falciparum dipeptidyl aminopeptidase I participates in vacuolar hemoglobin degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 279:43000–43007. 10.1074/jbc.M408123200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonis N., Crespo-Ortiz M.P., Bottova I., Abu-Bakar N., Kenny S., Rosenthal P.J., and Tilley L.. 2011. Artemisinin activity against Plasmodium falciparum requires hemoglobin uptake and digestion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:11405–11410. 10.1073/pnas.1104063108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.W., Annoura T., Sajid M., Chevalley-Maurel S., Ramesar J., Klop O., Franke-Fayard B.M., Janse C.J., and Khan S.M.. 2011. A novel ‘gene insertion/marker out’ (GIMO) method for transgene expression and gene complementation in rodent malaria parasites. PLoS ONE. 6:e29289 10.1371/journal.pone.0029289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Istvan E.S., Gluzman I.Y., Gross J., and Goldberg D.E.. 2006. Plasmodium falciparum ensures its amino acid supply with multiple acquisition pathways and redundant proteolytic enzyme systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:8840–8845. 10.1073/pnas.0601876103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na B.K., Bae Y.A., Zo Y.G., Choe Y., Kim S.H., Desai P.V., Avery M.A., Craik C.S., Kim T.S., Rosenthal P.J., and Kong Y.. 2010. Biochemical properties of a novel cysteine protease of Plasmodium vivax, vivapain-4. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e849 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platel D.F., Mangou F., and Tribouley-Duret J.. 1999. Role of glutathione in the detoxification of ferriprotoporphyrin IX in chloroquine resistant Plasmodium berghei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 98:215–223. 10.1016/S0166-6851(98)00170-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponpuak M., Klemba M., Park M., Gluzman I.Y., Lamppa G.K., and Goldberg D.E.. 2007. A role for falcilysin in transit peptide degradation in the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Mol. Microbiol. 63:314–334. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., von Seidlein L., Valecha N., Nosten F., Baird J.K., and White N.J.. 2014. Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14:982–991. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer E., Turrini F., and Arese P.. 1994. A luminescence method for the quantitative determination of phagocytosis of erythrocytes, of malaria-parasitized erythrocytes and of malarial pigment. Br. J. Haematol. 88:740–745. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijwali P.S., Koo J., Singh N., and Rosenthal P.J.. 2006. Gene disruptions demonstrate independent roles for the four falcipain cysteine proteases of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 150:96–106. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomianny C., Prensier G., and Charet P.. 1985. Comparative ultrastructural study of the process of hemoglobin degradation by P. berghei (Vincke and Lips, 1948) as a function of the state of maturity of the host cell. J. Protozool. 32:1–5. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaccapelo R., Janse C.J., Caterbi S., Franke-Fayard B., Bonilla J.A., Syphard L.M., Di Cristina M., Dottorini T., Savarino A., Cassone A., et al. 2010. Plasmepsin 4-deficient Plasmodium berghei are virulence attenuated and induce protective immunity against experimental malaria. Am. J. Pathol. 176:205–217. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S., Hardt M., Choe Y., Niles R.K., Johansen E.B., Legac J., Gut J., Kerr I.D., Craik C.S., and Rosenthal P.J.. 2009. Hemoglobin cleavage site-specificity of the Plasmodium falciparum cysteine proteases falcipain-2 and falcipain-3. PLoS ONE. 4:e5156 10.1371/journal.pone.0005156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwanarusk R., Russell B., Chavchich M., Chalfein F., Kenangalem E., Kosaisavee V., Prasetyorini B., Piera K.A., Barends M., Brockman A., et al. 2007. Chloroquine resistant Plasmodium vivax: in vitro characterisation and association with molecular polymorphisms. PLoS ONE. 2:e1089 10.1371/journal.pone.0001089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid A., Ranjan R., Smythe W.A., Hoppe H.C., and Sharma P.. 2010. PfPI3K, a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase from Plasmodium falciparum, is exported to the host erythrocyte and is involved in hemoglobin trafficking. Blood. 115:2500–2507. 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.