Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA) is a prevalent autoimmune disease with ten known susceptibility loci. Here we perform the first meta-analysis in AA by combining data from two genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and replication with supplemented ImmunoChip data for a total of 3,253 cases and 7,543 controls. The strongest region of association is the MHC, where we fine-map 4 independent effects, all implicating HLA-DR as a key etiologic driver. Outside the MHC, we identify two novel loci that exceed statistical significance, containing ACOXL/BCL2L11(BIM) (2q13); GARP (LRRC32) (11q13.5), as well as a third nominally significant region SH2B3(LNK)/ATXN2 (12q24.12). Candidate susceptibility gene expression analysis in these regions demonstrates expression in relevant immune cells and the hair follicle. We integrate our results with data from seven other autoimmune diseases and provide insight into the alignment of AA within these disorders. Our findings uncover new molecular pathways disrupted in AA, including autophagy/apoptosis, TGFß/Tregs and JAK kinase signaling, and support the causal role of aberrant immune processes in AA.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is one of the most prevalent autoimmune diseases, with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,1 and is the most common cause of hair loss in children. In AA, aberrant immune destruction is targeted to the hair follicle resulting in non-scarring hair loss that typically begins as patches, which can increase in size and coalesce and may progress to cover the entire scalp (alopecia totalis, AT), and body as well (alopecia universalis, AU). Disease prognosis is unpredictable and highly variable. Its etiologic basis has remained largely undefined, creating barriers to the development of effective therapeutic strategies and an enormous unmet medical need.2,3

Our first GWAS in AA identified associations in eight regions of the genome which were subsequently confirmed in independent candidate gene studies.4-7 Associated loci outside the HLA highlight particular immune response pathways and also implicate genes expressed in the hair follicle. For example, several regions contain genes with Treg functions, including IL2RA, IL2/IL21, CTLA4 and Eos, whereas ULBP3/ULBP6 implicate NKG2D mediated cytotoxic T-cells. Within the hair follicle, expression of STX17 suggests a role for end-organ autophagy, while PRDX5 implicates oxidative stress. A combined analysis of this GWAS and a subsequent replication study led to the identification of IL13/IL4 and KIAA0350/CLEC16A as new gene loci.5

Here we perform a meta-analysis to expand our sample size and identify two new loci that exceed our threshold for genome-wide significance and a third locus that is nominally significant. We identify transcripts and/or protein for candidate genes at all three loci in disease relevant tissues. We perform imputation and fine-mapping of the HLA identifying four independent associations that implicate HLA-DRβ1. Finally, CPMA of our data with published results from seven other autoimmune diseases identify molecular pathways shared by AA and one or more other disorders.

Results

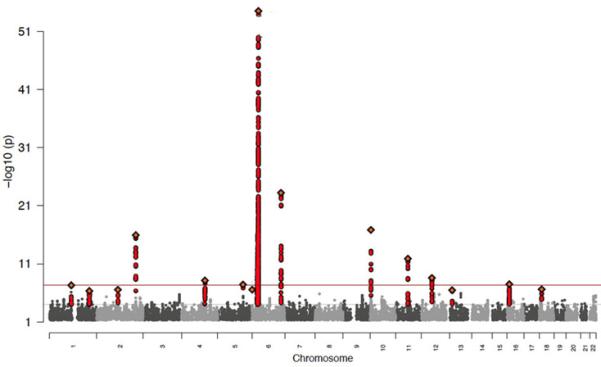

In this study, we have increased our cohort size and performed a combined analysis of two GWAS using Illumina Human660W- and Omni1-Quad BeadChips, analyzing a total of 2,489 cases and 5,287 controls ascertained in the US and Central Europe (Supplementary Table 1). Association analyses are performed with logistic regression. In a meta-analysis of these data, nine of the previously implicated regions exceeded statistical significance (p<5×10−8), with STX17 achieving nominal significance (rs10124366; p=1.09×10−5) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Data 1).

Figure 1. Manhattan plot for genome-wide tests of association in meta-analysis.

In order to conduct a meta-analysis across two GWAS, genotypes were imputed for each data set yielding 1.2 million SNPs. Standard association analysis with logistic regression including PC covariates was performed within each cohort and results were combined with standard-error weighted meta-analysis.

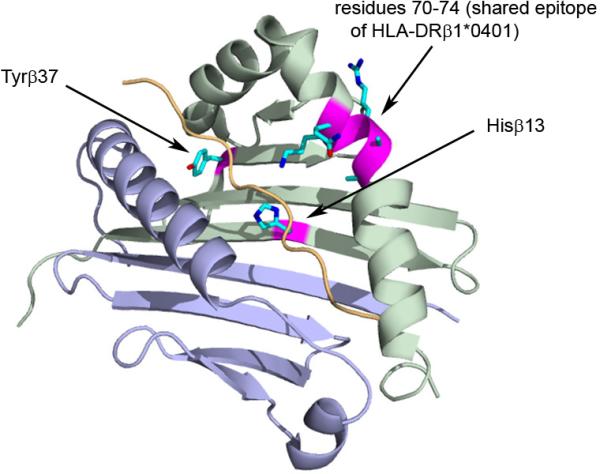

First, in order to resolve the MHC association signal (p = 4.91×10−58 for the best SNP, rs9275516), we used a published imputation and analysis protocol to perform fine-mapping (Supplementary Data 2).8 Conditional analysis revealed four independent variants located at the classical HLA-DRA and HLA-DRB1 genes. The most significant variant was amino acid position 37 in HLA-DRβ1 (omnibus p-value = 4.99×10−73). Of the five possible amino acids at this position, Leu (OR=1.56), Tyr (OR=1.54) and Phe (OR=1.19) conferred a higher risk of AA whereas the other residues conferred lower risk (OR for Asn=0.42; OR for Ser=0.74). Adjusting for the effects of HLA-DRβ1 amino acid position 37, we found an independent association due to an intronic SNP of HLA-DRA, rs9268657 (OR=0.63, p-value = 4.48E−41). Functional annotation of this SNP and its close proxies (R2>0.9) reveal that they influence expression levels of HLA-DRB1.9 Adjusting for both HLA-DRβ1 amino acid position 37 and rs9268657, we identified another independent association for the classical allele HLA-DRB1*04:01 (OR=1.64, p-value=1.76×10−12), confirming previous associations in candidate gene studies.10,11 Lastly, adjusting for HLA-DRβ1 amino acid position 37, rs9268657 and HLA-DRB1*04:01, amino acid position 13 in HLA-DRβ1 was also significant (p-value=4.57×10−16). Of the 6 possible alleles at this position, three increased risk (Tyr, OR=1.41; Ser, OR=1.35; Phe, OR=1.09), two are protective (His, OR=0.57; Gly, OR=0.50) and one demonstrated no effect (Arg, OR=0.98) (Supplementary Table 2). Further rounds of conditional analyses yielded no additional significant results (p>2.11×10−6).

Collectively, these four independent associations in the MHC implicate HLA-DR as the primary risk factor in AA, presumably through antigen presentation, similar to other immune-mediated diseases.12 For example, HLA-DRβ1 amino acid positions 13 and 37 contribute to P4 and P9 peptide-binding pockets respectively; the disease associations of HLA-DRB1*04:01 are thought to be driven by the shared epitope (amino acid residues 70-74),12 which also occur within the peptide binding cleft (Figure 2). Polymorphic residues within peptide binding pockets of HLA-DR influence binding affinities of peptides and thus may shape the repertoire of autoantigens capable of triggering or perpetuating disease.

Figure 2. Positions of amino acid residues demonstrating independent association with alopecia areata.

Structure of disease associated HLA-DRB1*04*01 allele and polymorphic residues involved in susceptibility to AA. The peptide binding cleft of an HLA-DR molecule is shown in cartoon representation with the α-chain colored in blue and β-chain in green. The MHC-bound peptide is shown in cartoon representation and colored yellow. Residues His13β and Tyr37β corresponding to amino acid positions with independent disease association are shown in stick model along with the shared epitope (residues 70-74). Crystal structure of HLA DR4 bound to melanocytes lineage-specific antigen gp120 was used (PDB 4IS6).

Next, we performed replication of SNPs in functionally relevant loci that achieved suggestive evidence for association in the meta-analysis (5×10−8>p>1×10−5), utilizing an independent cohort of Central European ancestry. The Immunochip was used to genotype 318 cases and 1,688 controls and a Sequenom assay was used to genotype 85 SNPs not included on the Immunochip in a cohort of 764 cases and 568 controls. This analysis identified statistically significant associations in two novel genomic regions: chromosome 2q13 containing ACOXL and BCL2L11 (rs3789129, p=1.51×10−8, ORA=1.3) and chromosome 11q13.5 containing C11orf30 and LRCC32 (rs2155219, p=1.25×10−8, ORT=1.2) (Table 1 and Supplementary Data 3).

Table 1.

Candidate genes in AA GWAS regions.

| Locus | Genes of Interest | SNP | Chr | BP | A1A2 | P | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6p21.32 | HLA-DQB1 | rs9275524 | 6 | 32,783,087 | TC | 1.8E-60 | 0.52 |

| 10p15.1 | IL15RA,IL2RA | rs3118470 | 10 | 6,141,719 | TC | 7.7E-21 | 0.71 |

| 2q33.2 | CD28,CTLA4,ICOS | rs231775 | 2 | 204,440,959 | AG | 2.2E-20 | 0.72 |

| 6q25.1 | RAET1L,ULBP3 | rs12183587 | 6 | 150,396,301 | TG | 5.9E-24 | 1.48 |

| 11q13 | PRDX5 | rs574087 | 11 | 63,859,524 | AG | 8.7E-14 | 1.32 |

| 12q13 | IKZF4 (Eos),ERBB3 | rs2292239 | 12 | 54,768,447 | TG | 4.4E-09 | 1.25 |

| 4q27 | IL21,IL2 | rs7682481 | 4 | 123,743,476 | CG | 4.8E-09 | 1.23 |

| 5q31.1 | IL13,1L4 | rs848 | 5 | 132,024,399 | AC | 4.8E-09 | 1.27 |

| 2q13 | ACOXL, BCL2L11(BIM) | rs3789129 | 2 | 111,414,511 | AC | 1.5E-08 | 1.31 |

| 11q13.5 | GARP(LRRC32) | rs2155219 | 11 | 75,976,842 | TG | 4.1E-08 | 1.21 |

| 1p13.2 | PTPN22 | rs2476601 | 1 | 114,179,091 | AG | 8.9E-08 | 1.34 |

| 12q24.12 | SH2B3(LNK),ATXN2 | rs653178 | 12 | 110,492,139 | TC | 1.6E-07 | 0.84 |

| 16p13.13 | CIITA,CLEC16A,SOCS1 | rs3862469 | 16 | 11101581 | TC | 1.7E-07 | 0.82 |

| 9q31.1 | STX17, NR4A3 | rs10124366 | 9 | 101,727,524 | AG | 1.1E-05 | 0.83 |

Fourteen regions in the genome have demonstrated association with AA by GWAS and replication. For each region, genes of interested are listed, along with the most significant SNP, its location in the genome, pvalue and OR obtained with logistic regression from the combined analysis (N=10,796).

P-values and effect estimates from each analytic stage are in Supplementary Table 3.

The association signal at chromosome 2q13 is located within an intron of ACOXL, and the region of association extends to include BCL2L11 (Figure 3). This region has been implicated in GWAS for two other autoimmune diseases: IgA Nephropathy and primary sclerosing cholangitis.13 ACOXL belongs to the acyl-CoA oxidase gene family. While other family members play well-studied roles in peroxisomal beta-oxidation, very little is known about the function of this gene. BCL2-like 11, also known as BIM, is a member of the BCL-2 protein family and contains a Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3) that interacts with other members to act as a pro-apoptotic factor. BIM has been widely studied in the context of apoptosis of immune cells, and has also been implicated in apoptosis of melanocytes.14 More recently data has emerged that implicates BIM in the destruction of some end-organs in autoimmune diseases, such as pancreatic beta cells in type 1 diabetes (T1D).15 Furthermore, BIM has also been shown to regulate autophagy,16 adding to growing evidence for the importance of this process in AA as recently shown by functional studies of STX17.17,18

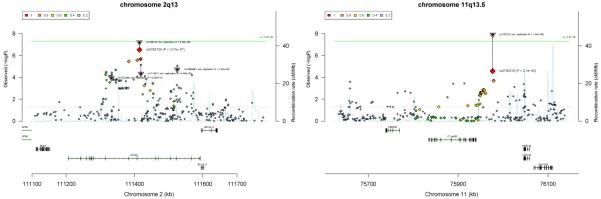

Figure 3. Detailed map of associated SNPs and gene locations for newly identified loci.

Two regions in the genome exceeded statistical significance when the replication data was combined with the meta analysis results (N=10,796) and analyzed with logistic regression. (a). Chromosome 2q13 includes ACOXL and BCL2L11. (b). Chromosome 12q24.12 included C11orf30 and LRCC32 (GARP).

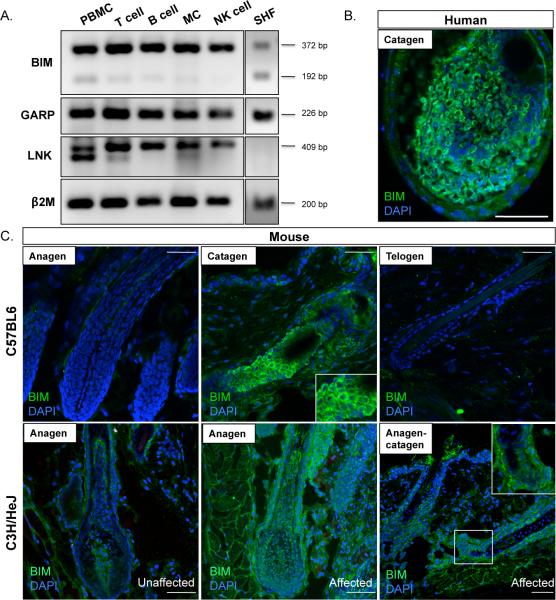

BIM is widely expressed in multiple cell types, including immune-related, epithelial and hair follicle cells.19 We first performed RT-PCR analysis of BIM expression in immune cells and scalp hair follicles. We detected BIM transcript in whole PMBCs, including T, NK, B, cells and monocytes (Figure 4A). In plucked human scalp hair follicles we observed expression of an alternative splice isoform, BIM-S, the most pro-apoptotic variant (Figure 4A).20,21 To characterize protein localization within hair follicles, we performed immunofluorescence staining on both human and mouse hair follicles. In the human hair follicle, BIM is highly expressed in the bulb of the hair follicle, especially within the matrix cells, in a pattern strikingly restricted to early catagen but not anagen or telogen (Figure 4B). The hair bulb matrix is the principal location of differentiated, pigment producing melanocytes, which are postulated to undergo apoptosis during catagen.22 In mouse hair follicles, BIM localized to the apoptosing strand and lower portion of the catagen hair follicle, consistent with its expression in human hairs. Remarkably, BIM expression was restricted to catagen hair follicles, where immunofluorescence staining performed on anagen or telogen hairs produced no signal (Figure 4C, upper panel). Finally, to investigate a possible role of BIM in AA pathogenesis, we utilized a mouse model that recapitulates genetic and molecular profiles of human AA.23 C3H/HeJ spontaneously develops AA and we performed immunofluorescence staining on affected and unaffected skin. We observed a striking and widespread increase in BIM expression throughout affected skin and hair follicles, that was not restricted to catagen hair follicles and appeared further upregulated in lesional skin (Figure 4C, lower panel). The regression stage of a normal cycling hair follicle, catagen, is characterized by apoptosis and cell death. We postulate that dysregulation of BIM in hair matrix keratinocytes and/or hair follicle melanocytes contributes to the early entry into dystrophic catagen in AA hair follicles in active disease.

Figure 4. Characterization BIM, GARP, and LNK expression.

A. BIM, GARP, and LNK expression in human immune cells and hair follicles. RT-PCR was performed on BIM, GARP, and LNK to determine gene expression in T cells, natural killer cells (NK), B cells, monocytes (MC), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and scalp hair follicles (SHF). 2M PCR was used as a loading control for each cDNA. Two splice variants are observed for β BIM expression: BIM-S (192 bp) and BIM-L (372 bp). Expected amplicon sizes: BIM (372 bp and 192 bp), GARP (226 bp), LNK (409 bp). B. Immunofluorescence staining in human hair follicles reveals that BIM is highly expressed in matrix cells of the catagen hair bulb. C. In healthy hair follicles from the C67BL6 mouse strain, BIM is strongly expressed in the apoptosing strand of mouse catagen hair follicles and is absent from anagen and telogen hair follicles. Immunofluorescence staining on affected and unaffected skin from the AA mouse model strain, C3H/HeJ, reveals that BIM expression levels and localization pattern are aberrant in affected hair follicles compared to unaffected C3H/HeJ and C57BL6 hair follicles.

The second novel region that exceeded statistical significance at chromosome 11q13.5 (rs2155219, P =1.25×10−8) contains three gene transcripts, including C11orf30, GUCY2E, and GARP (LRRC32). GWAS have implicated this region in several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (www.genome.gov/gwastudies). GARP is expressed on activated Tregs and binds and augments TGF beta bioavailability23-26, functioning to induce FOXP3 expression and Treg differentiation. Expression of GARP on activated human Treg cells correlates with their increased suppressive activity and GARP knockdown reduces their suppressive activity.24,27 Not surprisingly, we found that GARP is highly expressed in whole PBMCs, consistent with previous reports. Unexpectedly, we also detected a strong signal for GARP in plucked control scalp hair follicles, a site not previously described and perhaps atypical for the expression of a Treg protein (Figure 4). This suggests a potential role for GARP in hair biology and implicates significance of its disruption in AA at the site of pathology for the phenotype.

A third novel region on chromosome 12q24.12 that achieved suggestive evidence for association (p=1.3×10−7) is of interest because several genes harbored within the region functionally align with other associated genes. This region has demonstrated associations to multiple autoimmune diseases and contains 10 genes including SH2B adaptor protein 3 (SH2B3) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 family (ALDH2). SH2B3, also known as LNK, is a key negative regulator of cytokine signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases and JAK signaling. Two missense variants that confer increased cytokine production and enhanced signaling have been reported in the literature (rs3184504 and rs72650673).28,29 We genotyped these two functional polymorphisms in a sample of 96 chromosomes from AA patients carrying the AA associated risk allele (rs653178*G) and found that 93 chromosomes also carried the rs3184504*T risk allele (f=.97). This increase in allele frequency over what would be expected among a sample of European Americans (f=0.51 in Exome Variant Server ESP6500) indicates that there is strong LD between the AA associated risk variant and this functional polymorphism and suggests that R262W could be contributing to AA pathogenesis. The rs72650673*A allele was not found in our sample, consistent with its low allele frequency among European Americans (f=0.002 in Exome Variant Server ESP6500). We found by RT-PCR analysis that LNK is highly expressed in whole PBMCs, as well as T cells, natural killer, B cells, monocytes, but did not detect expression in plucked scalp hair follicles (Figure 4). ALDH2 has been identified as a citrullinated antigen in RA patients.30 This gene has been studied in the skin, with expression localizing to epidermis, sebaceous glands and hair follicles, where it is hypothesized to reduce the accumulation of oxidative stress-induced aldehydes.31

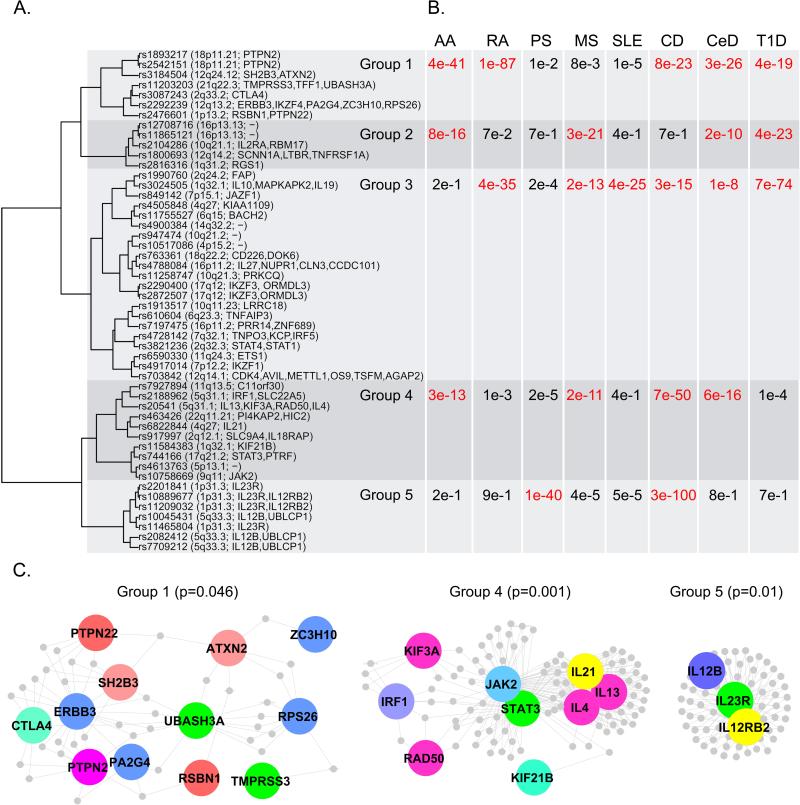

The strong association with HLA class II in AA, points towards the involvement of CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis. The importance of this T cell subset is supported by the presence of perifollicular CD4+ T cells in addition to intrabulbar CD8+ T cells in human AA. Finally, we analyzed these data in the context of other autoimmune disease by performing a cross phenotype meta-analysis using the 107 SNPs used in the original description of the analysis and data from seven other autoimmune disease.32 We found 50 SNPs that had significance at or near significance across two or more diseases, and clustering of these according to their association with disease identified five groups (Figure 5 A,B). Protein-protein interaction graphs of each SNP cluster demonstrate that for several of the groups, the proteins coded from these regions interact either directly or via an intermediary to a significant degree (Figure 5C). Integration of AA into the CPMA demonstrates mechanistic alignment with celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease, with most of the overlap coming from the first cluster of genes.

Figure 5. Cross Phenotype Meta-Analysis revealing functional clusters of genes and proteins indicating patterns of shared disease mechanisms across autoimmune diseases.

(A). 50 SNPs with evidence of association to more than one autoimmune disease (Pcpma < 0.01) are clustered by association with disease. (B). For each cluster and disease pair, a cumulative association statistic was calculated using Fisher's omnibus test to combine p- values. The varying pattern of disease association for each cluster suggests each group represents a distinct co-morbid mechanism. (C). Proteins coded within a 100 Mb window centered on each SNP within each cluster are depicted in protein-protein interaction maps. Three of the five clusters have significant protein inter-connectivity (permuted P < 0.05).

Collectively, this meta-analysis for the first time resolves HLA associations and demonstrates the pivotal etiological role of HLA-DR. Furthermore, the identification of specific residues in HLA-DRβ1 that are overrepresented among AA patients will allow us to better model peptide class II MHC interactions and thus predict autoantigens in AA. Associations outside HLA provide new evidence for the importance of Treg maintenance and immune response pathways in AA. Furthermore, autophagy and apoptosis are emerging as processes of etiologic importance in AA. These insights will allow us to better understand the molecular taxonomy of autoimmune diseases and the alignment of AA within this class of disorders. Importantly, as GWAS help to resolve disease mechanisms and identify pathogenic pathways perturbed in AA and autoimmunity in general, these approaches advance the field towards precision medicine in autoimmunity.

Methods

Patient Population

All participating studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards and ethics committees at Columbia University; MD Anderson Cancer Center; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; University of Colorado, Denver; University of California, San Francisco; and the Universities of Bonn, Düsseldorf, Münster, Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich, Germany; and Antwerp, Belgiumand were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. All study subjects provided written informed consent.

For the previously published GWAS and the ImmunoChip samples, cases were ascertained through the National Alopecia Areata Registry (NAAR), which recruits patients in the United States through five clinical sites and confirms diagnosis. Control data for these samples were obtained from publically available data. There were two sources of control data for the GWAS.4 First, a dataset was obtained from subjects enrolled in the New York Cancer Project (NYCP)33 and genotyped as part of previous studies.34 Second, a dataset was obtained from the CGEMS breast35 and prostate36 cancer studies (http://cgems.cancer.gov/data/). The ImmunoChip control data was obtained from the NIDDK inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) genetics consortium (http://medicine.yale.edu/intmed/ibdgc/index.aspx). The cases and controls for the previously unreported GWAS were ascertained from outpatient clinics, private dermatology practices and via AA self-support groups in Belgium and Germany. Inclusion criteria followed published guidelines,37 and additionally included diagnosis by a trained and experienced clinician. European GWAS controls included population-based controls established within the National Genome Research Network for use as universal controls (PopGen38, KORA39), and the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) Study40 and an additional population-based cohort from the HNR40 study. Sample counts by ascertainment location and genotyping platform are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes by salting out with saturated NaCl solution according to standard methods, or by using a Chemagic Magnetic Separation Module I (Chemagen, Baesweiler, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Whole genome genotyping for the meta analayis was performed on either Illumina HumanHap550 BeadChip or the Illumina Omni express, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The replication cohort was genotyped with the Illumina Immunochip. Additionally, SNPs selected for replication that are not present on the Immunochip were genotyped on the MassArray system using a Sequenom Compact MALDI-TOF device and iPLEX Gold reagents (Sequenom, San Diego, CA) in multiplex reactions. Primer sequences and standard assay conditions are available upon request. Standard quality control metrics were employed, removing data for SNPs and samples with call rates less than 90. Additional genotyping was performed by standard PCR based techniques.

Discovery QC and Imputation

Technical quality control was performed with quality control conducted on each dataset separately using a common approach. The following quality control parameters were applied: (i) missing rate per SNP < 0.05 (before sample removal below), (ii) missing rate per individual < 0.02, (iii) heterozygosity per individual ± _0.2, (iv) missing rate per SNP < 0.02 (after sample removal above), (iv) missing rate per SNP difference in cases and controls < 0.02, (vi) Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (in controls) P < 10−6, (vii) Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (in cases) P < 10−10. Study sample sizes varied between 1,200 and 3,000 individuals. The number of SNPs per study after quality control varied between 420,000 and 640,000. On average, the quality control processes excluded 44 individuals per study (with a range of 13–107 individuals) and 13,000 SNPs per study (with a range of 3,000–20,000 SNPs). After quality control, the GWAS datasets together comprised 2489 cases and 5287 controls and, for the next steps of the ‘genetic quality control’ analysis, a set of 221,784 SNPs common to all platforms and successfully genotyped in each GWAS sample was extracted. These SNPs were then further pruned to remove LD (leaving no pairs with r2 > 0.05) and lower frequency SNPs (minor allele frequency < 0.05), leaving 64,099 SNPs suitable for robust relatedness testing and population structure analysis (see below). Imputation of untyped SNPs was performed within each study in batches of 300 individuals. These batches were randomly drawn in order to keep the same case-control ratio as in the total sample from that study. We used Beagle 3.13. Imputation was performed with CEU+TSI HapMap phase 3 data (UCSC hg18/NCBI 36) using a chunk size of 10Mb with 410 phased haplotypes comprising 1,233,578 SNPs, using default parameters. Lambda-GC was carefully monitored before and after imputation.

Genetic quality control included relatedness testing and principal components analyses based on 64,099 LD independent SNPs, present on all platforms in this study. Relatedness testing was done with PLINK,41 reporting pairs with genome identity (pi-hat) > 0.9 as ‘identical samples’ and with pi-hat > 0.2 as being closely related. After random shuffling, one individual from each related pair was excluded from downstream analysis. From groups with multiple related pairs (for example, a family), only one individual was kept.

Discovery principal component analysis

Principal component estimation was done with the same collection of SNPs on the non-related subset of individuals. We estimated the first 20 principal components and tested each of them for phenotype association (using logistic regression with study indicator variables included as covariates) and evaluated their impact on the genome-wide test statistics using Lamda-GC (the genomic control inflation factor based on the median Chi-square) after genome-wide association of the specified principal component. Based on this we decided to include principal components 1,2,3,4,5,6 for downstream analysis as associated covariates.

Association analysis

The primary scan had a total of 2,332 QC+ cases and 5,233 QC+ controls. Association testing was carried out in PLINK,41 using the dosage data from the imputation and using the first six principal components as covariates, chosen as described above from the first 20 principal components. The four datasets had Lamda GC values of 1.025, 1.041, 1.040 and 1.042. A fixed-effect meta-analysis was performed using odds ratios and standard errors. The final meta-analysis had a Lambda GC of 1.076.

MHC imputation and association analysis

Starting from the genotyped SNPs we imputed classical HLA alleles and corresponding polymorphic amino acids within classical HLA proteins, following a recently described protocol.8 In total 8,271 variants including SNPs, amino acids and classical HLA alleles at 2- and 4- digit resolution were tested for association in the MHC region. Logistic regression was applied for testing for association, including the 6 first principal components and a dummy variable for the cohort id of each sample. Single test association was performed for all types of variants as well as omnibus tests for the amino acids. The conditional analyses were performed by using the initial PCA covariates, the dummy variable for cohort, and adjusting for the top and conditional hits.

Analysis of Immunochip data

To identify the sample ethnicities in the case cohort, we calculated the principal components (PC) 1 and 2 using Hapmap 3, and mapped the case samples to the PCs. Samples that do not cluster with the Hapmap3 European samples were discarded. The NIDDK control cohort has been cleaned for sample ethnicity and is thus not necessary to undergo such procedure. For both case and control cohort, we then removed samples that have missing genotype rate > 2% and variants that have missing genotype rate > 2% for each cohort. For the control cohort, we additionally removed variants that fail the Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium test (p-value<1×10−5). The case and the control cohorts were then merged, and we removed variants that have different missingness in cases and in controls (p-value<1×10−5) and samples that have high heterozygosity (>3 standard deviation). We used PLINK to infer the genetic relationships between the remaining samples and we randomly removed one of the samples for each related sample pair (PI_HAT>0.5).41 The final cleaned dataset has 318 cases and 1688 controls. We tested the association between the genetic variants and alopecia areata using PLINK with the principal components 1-5 as covariates.

RT-PCR and immunofluorescence staining on human and mouse tissues

RT-PCR was performed on total RNA extracted from plucked human scalp hair follicles (SHF) and T cells, natural killer cells (NK), B cells, monocytes (MC), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) that were isolated by FACS from whole blood. The primer sequences of the BIM, GARP, LNK, and β2M genes are as follows: BIM F: 5’- TAAGTTCTGAGTGTGACCGAGA-3’, R: 3’- CCATTGCACTGAGATAGTGGTTG-5’; GARP F: 5’-CGCTCCCGAGACTCATCTAC-3’, R: 5’-AGGTGCTCAAGAAAGCTGTCG-3’; LNK F: 5’-GTGGGGAATACGTGCTCACTT-3’, R: 5’-TGTCCACGACCGAGGGAAA-3’; β2M F: 5’-GAGGCTATCCAGCGTACTCCA-3’, R: 5’- CGGCAGGCATACTCATCTTTT-3’.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on human and mouse samples. Human skin and hair follicle sections were obtained from control occipital scalp biopsies discarded during surgery and considered to be non-human subject research under 45 CFR Part 46 (IRB exempted). Mouse anagen skin (day 30), catagen skin (day 42) and telogen skin (day 50) was harvested from the dorsal region and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (O.C.T.) for sectioning (10 μm). Slides were fixed with 50% MeOH/50% Acetone for 10 minutes at 220uC, washed with 1X PBS, and then blocked with 2% fish skin gelatin (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA). The α-BIM antibody (Rabbit) (Biorbyt, orb10190) was used at a concentration of 1:200 for both mouse and human studies. Slides were washed, incubated with the Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) secondary antibody (1:800 in 1X PBS), mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and imaged using a LSM 5 laser-scanning Axio Observer Z1 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Cross Phenotype Meta-Analysis

The protocol for this analysis was adopted from previously described work on cross phenotype meta-analysis. 43 Using Dataset S1 from the supplementary data section of the original analysis, we added in AA association p-values for the 107 SNPs originally investigated. For SNPs with no p-value, we used Broad Institutes SNAP to find a proxy SNP with r2 > 0.9 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/). The CPMA statistic was then recalculated for all 107 SNPs using code (found here: http://coruscant.itmat.upenn.edu/software.html) implementing the original description. All SNPs meeting a significance threshold of < 0.01 were included in clustering analysis. Clustering was done by first binning p-values into four groups based on magnitude and clustered using the cluster package. Cumulative association statistics were calculated in R using Fisher's omnibus test. Protein-protein interaction analysis was performed using DAPPLE, a publicly available web application (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/dapple). Settings for DAPPLE included the 1000 genome assembly, 5000 permutations, and 50kb regulatory region upstream and downstream. All statistical analysis was performed in R version 3.0.1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to the many patients and their family members who participated in this study. We are thankful to Drs. Lawrence Shapiro and Tatyana Gindin for guidance on the structural effects of HLA associations. We thank Spandon V. Shah, Holly Jiang, Matthew Ding, and Steven Chiu for their assistance and contributions in isolating the immune cells by FACS and Jane E. Cerise for her bioinformatic expertise. We are most grateful for the support of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation for funding the initial studies, and Ms. Vicki Kalabokes and her staff at NAAF for their efforts on our behalf. The US patient cohort was collected and maintained by the National Alopecia Areata Registry (N01- AR62279) (to M.D.). Some controls were drawn from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (HNR) cohort, which was established with the support of the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation. RCB and MMN are members, TB is an associate member, of the DFG-funded Excellence Cluster ImmunoSensation. RCB is a recipient of a Heisenberg Professorship of the German Research Foundation (DFG). This work was supported in part by the DFG grant BE 2346/5-1 as well as by local funding (BONFOR) to R.C.B. and USPHS NIH/NIAMS grants R01AR52579 and R01AR56016 (to A.M.C.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions. RB, MN, SR, MD, VP, MH, DN, and JMW participated in phenotyping, diagnosis, and access to patient samples. LP performed technical aspects in preparation of samples for genotyping and data transfer. HH, LP, SR, TY, TB, AM, PIWD performed statistical analyses. GMD performed immunofluorescence staining and RT-PCR experiments. AL and PKG provided control samples and performed genotyping as well as insight into autoimmune diseases. CIA provided additional statistical advice and control samples. LP contributed to study design, interpretation of results, and drafting of the manuscript. RB, MN, MD, DA, and AMC provided conceptual guidance to the project. ADJ, RC, AM, and PIWD provided expertise on interpreting HLA results. AMC additionally supplied input into the functional significance of candidate genes, supervision of lab personnel, management of collaborations, preparation of the manuscript and all reporting requirements for granting agencies.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ., 3rd Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628–633. doi: 10.4065/70.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delamere FM, Sladden MM, Dobbins HM, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for alopecia areata. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2008:CD004413. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004413.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebwohl M. Treatment of skin disease : comprehensive therapeutic strategies. 2nd edn Mosby/Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petukhova L, et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature. 2010;466:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature09114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagielska D, et al. Follow-Up Study of the First Genome-Wide Association Scan in Alopecia Areata: IL13 and KIAA0350 as Susceptibility Loci Supported with Genome- Wide Significance. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John KK, et al. Genetic variants in CTLA4 are strongly associated with alopecia areata. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2011;131:1169–1172. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redler S, et al. Investigation of selected cytokine genes suggests that IL2RA and the TNF/LTA locus are risk factors for severe alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1360–1365. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia X, et al. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lappalainen T, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Entz P, et al. Investigation of the HLA-DRB1 locus in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombe BW, Lou CD, Price VH. The genetic basis of alopecia areata: HLA associations with patchy alopecia areata versus alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:216–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raychaudhuri S, et al. Five amino acids in three HLA proteins explain most of the association between MHC and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:291–U291. doi: 10.1038/ng.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melum E, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in primary sclerosing cholangitis identifies two non-HLA susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;43:17–19. doi: 10.1038/ng.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouillet P, Cory S, Zhang LC, Strasser A, Adams JM. Degenerative disorders caused by Bcl-2 deficiency prevented by loss of its BH3-only antagonist Bim. Developmental cell. 2001;1:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santin I, et al. PTPN2, a candidate gene for type 1 diabetes, modulates pancreatic beta- cell apoptosis via regulation of the BH3-only protein Bim. Diabetes. 2011;60:3279–3288. doi: 10.2337/db11-0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo SQ, Rubinsztein DC. BCL2L11/BIM A novel molecular link between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2013;9:104–105. doi: 10.4161/auto.22399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamasaki M, et al. Autophagosomes form at ER-mitochondria contact sites. Nature. 2013;495:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Mizushima N. The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151:1256–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Reilly LA, et al. The proapoptotic BH3-only protein bim is expressed in hematopoietic, epithelial, neuronal, and germ cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157:449–461. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogueira TC, et al. GLIS3, a susceptibility gene for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, modulates pancreatic beta cell apoptosis via regulation of a splice variant of the BH3-only protein Bim. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang CC, et al. Apoptosis of human melanoma cells induced by inhibition of B RAFV600E involves preferential splicing of bimS. Cell death & disease. 2010;1:e69. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobin DJ. Aging of the hair follicle pigmentation system. International journal of trichology. 2009;1:83–93. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.58550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Battaglia M, Roncarolo MG. The Tregs' world according to GARP. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:3296–3300. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran DQ, et al. GARP (LRRC32) is essential for the surface expression of latent TGF- beta on platelets and activated FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:13445–13450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockis J, Colau D, Coulie PG, Lucas S. Membrane protein GARP is a receptor for latent TGF-beta on the surface of activated human Treg. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:3315–3322. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang R, et al. GARP regulates the bioavailability and activation of TGFbeta. Molecular biology of the cell. 2012;23:1129–1139. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, et al. Expression of GARP selectively identifies activated human FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13439–13444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901965106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhernakova A, et al. Evolutionary and functional analysis of celiac risk loci reveals SH2B3 as a protective factor against bacterial infection. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;86:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMullin MF, Wu C, Percy MJ, Tong W. A nonsynonymous LNK polymorphism associated with idiopathic erythrocytosis. American journal of hematology. 2011;86:962–964. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegner N, et al. Autoimmunity to specific citrullinated proteins gives the first clues to the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:34–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung C, Davies NG, Hoog JO, Hotchkiss SAM, Pease CKS. Species variations in cutaneous alcohol dehydrogenases and aldehyde dehydrogenases may impact on toxicological assessments of alcohols and aldehydes. Toxicology. 2003;184:97–112. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotsapas C, et al. Pervasive sharing of genetic effects in autoimmune disease. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell MK, Gregersen PK, Johnson S, Parsons R, Vlahov D. The New York Cancer Project: rationale, organization, design, and baseline characteristics. J Urban Health. 2004;81:301–310. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plenge RM, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter DJ, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies alleles in FGFR2 associated with risk of sporadic postmenopausal breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:870–874. doi: 10.1038/ng2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeager M, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:645–649. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olsen EA, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines--Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krawczak M, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community genetics. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wichmann HE, Gieger C, Illig T, Group MKS. KORA-gen--resource for population genetics, controls and a broad spectrum of disease phenotypes. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S26–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmermund A, et al. Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcium and Lifestyle. Am Heart J. 2002;144:212–218. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeStefano GM, et al. Mutations in the Cholesterol Transporter Gene ABCA5 Are Associated with Excessive Hair Overgrowth. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cotsapas C, et al. Pervasive sharing of genetic effects in autoimmune disease. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.