Abstract

Background. WHO's recommendation of HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) as diagnostic for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was adopted by three UK London boroughs in May 2012. The South London Diabetes (SOUL-D) study has recruited people with newly diagnosed T2DM since 2008. We compared participants diagnosed before May 2012 with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol to those with diagnostic HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol. Methods. A prospective cohort study of newly diagnosed T2DM participants from 96 primary care practices, comparing demographic and biomedical variables between those with diagnostic HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol or HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol at recruitment and after one year. Results. Of 1488 participants, 22.8% had diagnostic HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol. They were older and more likely to be white (p < 0.05). At recruitment and one year, there were no between-group differences in the prevalence of diabetic complications, except that those diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol had more sensory neuropathy at recruitment (p = 0.039) and, at one year, had new myocardial infarction (p = 0.012) but less microalbuminuria (p = 0.012). Conclusions. Use of HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol as the sole T2DM diagnostic criterion may miss almost a quarter of those previously diagnosed in South London yet HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol may not exclude clinically important diabetes.

1. Introduction

The use of plasma glucose, measured after fasting and a standardised oral glucose load, for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has long been considered inconvenient [1]. Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), formed in a nonenzymatic reaction between glucose and haemoglobin and reflecting a 2-3-month average of plasma glucose concentrations in a single random sample [2], was considered as an alternative diagnostic tool for T2DM by an International Expert Committee in 2009 [1]. It has both advantages and disadvantages, [2] but in 2010 and 2011, respectively, both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [3] and World Health Organisation (WHO) [4] proposed that HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) is diagnostic of T2DM, based on successive reproducible data from a number of publications linking HbA1c concentrations and diabetes specific complications, notably retinopathy [5–8].

Prior to this, people in South London, in the United Kingdom [9], were diagnosed with diabetes by plasma glucose measurements, with or without formal glucose tolerance tests, although HbA1c was measured at diagnosis for assessment and monitoring purposes. The authorities providing healthcare to a large area of South London did not adopt WHO's recommendations of HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) as the diagnostic tool for T2DM until May 2012 [10]. Four years earlier, in May 2008, the South London Diabetes Study (SOUL-D) had begun recruiting adults with new-onset diabetes from 96 primary care practices in the London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham into an observational cohort study [11]. The majority were diagnosed prior to May 2012 using plasma glucose values. SOUL-D created an opportunity to examine how well HbA1c would perform compared to previously used methods for diagnosing diabetes in this multiethnic, high-risk population.

The aims of this study were to examine the proportion of participants in the SOUL-D cohort that were diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) before the new guidelines were introduced; determine whether these participants were significantly different from participants with higher HbA1c at diagnosis in their demography and diabetes complications; and investigate the criteria used to diagnose diabetes in patients with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%).

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Subjects

One thousand seven hundred and fifteen people with newly diagnosed T2DM diagnosed before May 2012 were recruited from 96 (70% eligible) consenting primary care practices in the London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham, which serve a diverse population of almost one million residents. The ethnic origin of the boroughs' population is 66.6% white, 20% black, and 13.4% South Asian [9]. Eligible participants were aged 18–75 years and had been diagnosed with T2DM within the last 6 months. Exclusion criteria included being a temporary resident, people diagnosed with diabetes other than T2DM, known severe mental illness (dementia, bipolar disorder, substance dependence, and personality disorder), severe advanced diabetes complications (e.g., being registered blind, requiring dialysis, or above knee amputation), and those not fluent in English (estimated at 7% [9]).

2.2. Methods

This was a prospective cohort study comparing 2 participant groups: those diagnosed with T2DM with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) and those diagnosed with HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%). The protocol for recruitment of participants in SOUL-D has been published previously [11], but, in brief, potential participants were identified by 6 monthly practice database reviews and invited to participate if they had a new diagnosis of T2DM.

Consenting patients attended their primary care practice to meet a SOUL-D researcher with whom they completed a standardised interview including medical history, employment status, education history (years of education attended), physical examination, and blood test. This was completed within 6 months of diagnosis (recruitment data) and 12 months after recruitment (one-year data). Additional clinical data from the time of diagnosis (diagnostic data), including HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, urinary albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR), and lipid profile (low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides), were extracted from each participant's medical records to give preintervention parameters. Cross-sectional analysis was undertaken to compare diagnostic and recruitment clinical and sociodemographic variables between those participants whose diagnostic HbA1c had been <48 mmol/mol and those with higher diagnostic values. Analysis of year 1 study follow-up data was also undertaken to see if early progression of diabetes (reflected by HbA1c and treatment prescribed) varied between groups.

For cross-sectional baseline (diagnostic and recruitment) analysis, age, gender, and self-reported ethnicity (using the 2001 consensus classification [9]) were noted at recruitment. Date of diabetes diagnosis and HbA1c at diagnosis were recorded from medical records. Macrovascular complications, myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke/cerebrovascular accident (CVA), were defined by history given at recruitment and confirmed by examination of medical records. BMI (kg/m2), blood pressure (mmHg), foot examination, and sensory neuropathy were determined at recruitment, the last using vibration perception threshold >25 volts measured by neurothesiometer (Scientific Laboratory Supplies, Wilford, Nottingham). Retinopathy status was obtained from the Diabetes Eye Complications Screening (DECS) service, the local community based eye photography service used in all three boroughs, using digital two-field retinal photographs and the English Retinopathy Minimum grading [12]. Fasting blood was taken for HbA1c and lipid measurements. Microalbuminuria was defined on a single ACR measurement in the records of >3 μg/mg. Medication status (presence or absence of oral hypoglycemic agents and insulin) at recruitment was recorded from patient history, confirmed from the participants' medical records.

One year follow-up assessment was made within a 3-month window of 12 months after recruitment. The data collection made at recruitment was repeated. If participants declined, data were obtained from their GP surgery (with permission) within a three-month window of their study appointment.

To determine the basis of diagnosis for each participant whose HbA1c was <48 mmol/mol (6.5%) at diagnosis, additional specific permission was granted to access the clinical database of 43 GP surgeries, selected for having ≥5 participants meeting the above criteria. Patient records were examined for details of symptoms at diagnosis (polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, blurred vision, and weight loss) and details of diagnostic testing (fasting plasma glucose (FPG), random plasma glucose (RPG), or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) glucose concentrations) were noted. The data were compared with the relevant WHO recommendations to assess the accuracy of the original diagnosis [6]. Case-by-case judgements on the diagnosis were made by 2 independent clinicians reviewing the data.

HbA1c (%) at diagnosis was measured in one of 3 local laboratories according to IFCC methods (aligned with the DCCT) based on HPLC and then quantified during capillary electrophoresis or electron spray ionization mass spectrometry. The assay methods used were (1) the Trinity Biotech Ultra 2 boronate affinity chromatography (coefficient variations (CV%) 0.82%, 0.91%, and 0.46% for normal, intermediate, and high HbA1c values based on 20 assays with the same run time), (2) the Trinity Biotech Premier Hb9210 analyser, also a boronate affinity chromatography-based high performance liquid chromatography system (CV% 1.62%, 1.59%, and 1.68% for low, medium, and high values, resp.), and (3) TOSOH G7 ion exchange with imprecision CV% less than or equal to 1.2%. For all three laboratories, the CV% was well below the recommended upper limit of 2% CV and there were no changes in the methodologies between 2008 and 2013. HbA1c samples measured at recruitment and one year were all measured in the central laboratory (method 1). Percentage (%) values were converted to mmol/mol by subtracting 2.15 then multiplying by 10.929 [13]. Lipid profiles and ACRs were measured using Siemens ADVIA 2400. The PEG-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay was used for urinary albumin and the Jaffe reaction for urinary creatinine.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 [14]. Data are presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)] where data were normally distributed, or median [interquartile range (IQR)] where data were skewed, which could not be corrected by log transforming the variables, or as a count (percentage) for categorical variables, all stratified by diagnostic HbA1c status. Unadjusted statistical analyses, comparing participants diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) to those with HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%), were conducted using one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous data and Mann-Whitney U analyses for nonnormally distributed continuous data (diagnostic variables: HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and BMI). Pearson chi-squared testing was used for comparisons of categorical data (ethnicity, age, gender, and the presence or absence of complications at recruitment and one year, as well as medication status). Binary logistic regression was performed to assess the association between demographic and diagnostic data (age at diagnosis, ethnicity, gender, diagnostic BMI, blood pressure, and lipid profile) and diagnostic HbA1c category (< or ≥48 mmol/mol (6.5%)), accounting for multiple comparisons. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the mean rate of change in glycaemia between both groups.

The study was approved by King's College Hospital Research Ethics Committee (reference 08/H0808/1). All participants gave informed consent.

3. Results

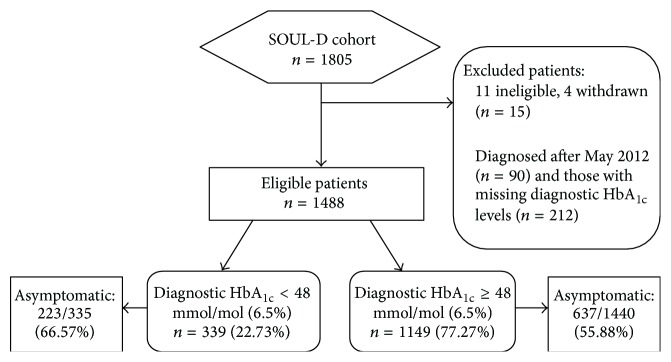

Of 1805 participants recruited into SOUL-D, this analysis was restricted to 1715 participants diagnosed before May 2012 (Figure 1). Fifteen participants were excluded for failing to meet inclusion criteria or withdrawing themselves and 212 were excluded because HbA1c was not documented at diagnosis. Of the remaining 1488, 55.11% were male (n = 820), mean age was 55.75 ± 11.02 years, and 50.13% (n = 746), 39.58% (n = 589), and 10.28% (n = 153) were of white, black, and South Asian/other ethnicity, respectively. Age and gender were not significantly different in those participants without HbA1c at diagnosis and the population diagnosed after May 2012 (all p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participants in the study.

Three hundred and thirty-nine participants (22.78%) had HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) at the time of diagnosis by glucose criteria. This group was significantly older (58.73 ± 10.36 versus 54.87 ± 11.07; p < 0.0001) but had no significant difference in gender split (p = 0.883, 55.46% versus 55.00% male for the <48 mmol/mol and ≥48 mmol/mol (6.5%) resp.) groups versus the higher HbA1c group Table 1. People of white ethnicity were overrepresented, while people of black and South Asian/other ethnicity were underrepresented (p < 0.0001). They had a significantly higher proportion of sensory neuropathy at recruitment but no significant differences in prevalence of retinopathy, microalbuminuria, MI, or stroke/CVA. In terms of nonglycemic cardiovascular risk at diagnosis, they had lower BMI and diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and total cholesterol (p < 0.01 for all) but no significant differences in systolic blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, or HDL-cholesterol. All but 7 participants (4 with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%)) had information on symptoms at presentation, with significantly more participants being asymptomatic at diagnosis in the low HbA1c group (68.96% versus 55.41%, p = 0.0001). At recruitment, the participants with low HbA1c at diagnosis group were significantly less likely to be receiving oral hypoglycemic agents (29.1% versus 61.9%, p < 0.0001) with a trend for fewer receiving insulin (1.78% versus 3.76%, p = 0.074). The group with low HbA1c at diagnosis were more likely to be retired but there were no reported differences in proportion in full- or part-time employment or years of education attended (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparisons between participants diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol and with HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol at diagnosis and recruitment.

| n with data | HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographical data | ||||

| Age | 1488 | 58.73 (±10.36) | 54.87 (±11.07) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% male) | 1488 | 188 (55.46) | 632 (55.00) | 0.8829 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 1488 | |||

| White | 218 (64.31) | 528 (45.95) | <0.0001 | |

| Black | 98 (28.91) | 491 (42.73) | ||

| Asian | 23 (6.78) | 130 (11.31) | ||

|

| ||||

| Median (IQR) HbA1c at diagnosis | ||||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 1488 | 44.26 (42.08–45.35), | 58.47 (51.91–82.52) | <0.0010 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.20 (6.00–6.30) | 7.50 (6.90–9.70) | ||

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular risk factors (SD) at diagnosis | ||||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1211 | 2.86 (±0.98) | 3.67 (±21.83) | 0.5313 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1251 | 1.28 (±0.67) | 1.24 (±0.44) | 0.1750 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1357 | 4.70 (±1.32) | 4.90 (±1.50) | 0.0053 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1273 | 1.40 (±0.85) | 1.59 (±1.29) | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1380 | 30.77 (±7.74) | 31.60 (8.40) | 0.0035 |

| BPS (mmHg) | 1409 | 133.96 (±16.84) | 134.65 (±16.28) | 0.5087 |

| BPD (mmHg) | 1409 | 80.00 (±11.00) | 82.00 (±12.00) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Complication status, HbA1c medication status at recruitment | ||||

| Retinopathy (%) | 1335 | 30 (9.43) | 80 (7.86) | 0.3749 |

| Microalbuminuria (%) | 1237 | 37 (12.76) | 158 (16.68) | 0.1279 |

| Sensory neuropathy (%) | 1368 | 32 (10.16) | 70 (6.65) | 0.0393 |

| MI (%) | 1482 | 24 (7.08) | 55 (4.81) | 0.1026 |

| Stroke (%) | 1479 | 8 (2.37) | 40 (3.50) | 0.3042 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 1395 | 42.08 (38.80–44.26) | 50.82 (45.35–60.65) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.00 (5.70–6.20) | 6.80 (6.30–7.40) | ||

| Receiving insulin (%) | 1481 | 6 (1.78) | 43 (3.76) | 0.0743 |

| Receiving oral diabetes agents (%) | 1470 | 97 (29.1) | 704 (61.9) | <0.0001 |

Table 2.

Employment and educational status.

| HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | |

|---|---|---|

| In full-time employment (%) | 430 (37.42) | 119 (35.10) |

| In part-time employment (%) | 123 (10.70) | 36 (10.62) |

| On sick leave (%) | 23 (2.00) | 9 (2.65) |

| Unemployed (%) | 189 (16.45) | 34 (10.03) |

| Medically retired (%) | 51 (4.44) | 18 (5.31) |

| Housewife/househusband (%) | 43 (3.74) | 6 (1.77) |

| Retired (%) | 289 (25.15) | 117 (34.51)∗ |

|

| ||

| Education status | ||

| Years of education (mean ± SD) | 13.19 ± 2.96 | 13.50 ± 3.15 |

∗ p = 0.0009, all other comparisons not significant.

When demographic and diagnostic data (age at diagnosis, ethnicity, gender, diagnostic BMI, blood pressure, and lipid profile) were entered into a multiple binary logistic regression, only being black (p < 0.001), South Asian/other (p = 0.009), age at diagnosis (p = 0.02), and triglyceride levels at diagnosis (p = 0.001) were significant predictors of whether participants were diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) or ≥48 mmol/mol (6.5%). The resulting model accounted for 7% of the variance and correctly identified 98.5% of cases.

3.1. Year One Analysis (Table 3)

Table 3.

Prospective comparisons between participants diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol and those diagnosed with HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol at year 1.

| n with data | HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) HbA1c at year 1 | ||||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 1251 | 43.17 (40.98–47.54), | 49.72 (45.35–57.37) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.10 (5.90–6.50) | 6.70 (6.30–7.40), | ||

|

| ||||

| New complication status at year 1 | ||||

| Retinopathy (%) | 1220 | 32 (10.88) | 126 (13.61) | 0.2257 |

| Microalbuminuria (%) | 1025 | 22 (9.21) | 123 (15.65) | 0.0123 |

| MI (%) | 1278 | 10 (3.38) | 12 (1.22) | 0.0124 |

| Stroke (%) | 1272 | 4 (1.4) | 7 (0.72) | 0.2951 |

|

| ||||

| Cumulative microalbuminuria and MI status at year 1 | ||||

| Microalbuminuria (%) | 1218 | 39 (14.77) | 191 (20.02) | 0.0540 |

| MI (%) | 1487 | 29 (8.55) | 59 (5.14) | 0.0190 |

|

| ||||

| Medication status at year 1 | ||||

| Receiving oral agents (%) | 1296 | 92 (30.6) | 715 (71.9) | <0.0001 |

| Receiving insulin (%) | 1294 | 8 (2.67) | 37 (3.72) | 0.3817 |

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular risk factor status (SD) at year 1 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1308 | 31.28 (±6.44) | 32.14 (±6.35) | 0.0400 |

| BPD (mmHg) | 1282 | 80.21 (±10.76) | 82.22 (±10.91) | 0.0057 |

| BPS (mmHg) | 1284 | 135.42 (±18.28) | 134.57 (±17.23) | 0.4614 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1164 | 2.49 (±0.80) | 2.51 (±0.84) | 0.7485 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1200 | 1.32 (±0.48) | 1.25 (±0.34) | 0.0081 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1234 | 4.40 (±1.30) | 4.40 (±1.20) | 0.0942 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1164 | 2.49 (±0.80) | 2.51 (±0.84) | 0.5454 |

| Smoking status (%) | 1149 | 190 (21.62) | 41 (15.19) | 0.0211 |

Of the 1488 participants in the study, 21.51% (n = 320) were not available for follow-up at year 1: 6 had died; 262 were not contactable; and 52 had withdrawn from the study.

HbA1c remained significantly lower in those participants with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) at diagnosis, p < 0.0001 (Table 3), and there was a significant difference in the change in HbA1c from recruitment to year 1 between the two groups (p < 0.001). Participants with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) at diagnosis showed a slight increase in HbA1c (median (IQR): 1.09 (−1.09–4.37) mmol/mol or 0.10 (−0.10–0.40)%), compared to a slight fall overall in the group with the high value at diagnosis (0.00 (−5.4645 to 4.3716) mmol/mol and 0.00 (−0.5000 to 0.400)%). BMI and diastolic blood pressure as well as smoking status were significantly lower and HDL cholesterol was significantly higher in the low HbA1c at diagnosis group (p < 0.05 for all), with no significant differences in systolic blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides between groups. A higher proportion of those with low HbA1c at diagnosis reported a new MI (3.38% versus 1.22%, p = 0.012). When the cumulative prevalence was compared between groups, that is, any MI events prior to year 1, the low HbA1c group remained significantly more likely to have past MI (8.55% versus 5.14%, p = 0.019). Numbers were very small, but, while there were no differences in a post hoc analysis between those with and without a history of MI at recruitment, three of those reporting new MI at year one were of black ethnicity and one was of Asian/other ethnicity, with none being white. Significantly fewer participants in the lower HbA1c group had developed new microalbuminuria (9.21% versus 15.65%, p = 0.012), and the cumulative prevalence of microalbuminuria prior to year 1 almost achieved significance (14.77% versus 20.02%, p = 0.054). Incidence of new retinopathy and stroke did not differ significantly between groups (all p > 0.1). A lower percentage of participants in the low HbA1c at diagnosis group were receiving oral hypoglycemic agents (30.6% versus 71.9%, p < 0.0001) but the difference between groups in those receiving insulin at one year did not achieve statistical significance (2.16% versus 4.22%, p = 0.145).

3.2. Review of Diagnosis in Low Diagnostic HbA1c Group (Table 4)

Table 4.

Basis for diagnosis in patients with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol.

| Basis of diagnosis | Asymptomatic and repeat test not performed | Incorrectly diagnosed according to WHO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting plasma glucose | 66 (37.71%) | 18 (27.27%) | 26 (39.39%) |

| OGTT | 68 (38.86%) | 21 (30.88%) | 34 (50.00%) |

| Random plasma glucose | 28 (16.00%) | 12 (42.86%) | 15 (53.57%) |

| HbA1c | 13 (7.42%) | 5 (38.46%) | 13 (100%) |

|

| |||

| Total (%) | 175 | 63 (36.00%) | 89 (50.86%) |

Information on diagnostic tests was obtained for 175 participants (51.62%) in the low HbA1c at diagnosis group from 43 practices. These 175 participants were not significantly different from the remainder of the group in terms of demographical and biomedical data (p > 0.05) for all factors studied. There were 38.86%, 37.71%, 16.00%, and 7.42% participants diagnosed on basis of 2-hour plasma glucose, fasting plasma glucose, random plasma glucose, and HbA1c measurements below the WHO recommendation (median (and IQR) for HbA1c 46.45 (45.35–46.45) mmol/mol or 6.40 (6.30–6.40)%). Sixty-three (36.0%) asymptomatic patients, for whom data were available, had no repeat or subsequent alternative test documented. Eighty-nine (50.86%) participants, for whom data were available, fell outside prevailing WHO criteria for T2DM diagnosis.

4. Discussion

The aims of this study were to estimate the proportion of individuals in an urban multiethnic cohort that might not be diagnosed with T2DM if HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol is the sole diagnostic criterion and assess whether individuals diagnosed on alternative criteria and not meeting the new criterion differed in terms of demographics and biomedical outcomes from those with HbA1c at diagnosis. In our cohort, almost a quarter of people previously diagnosed with T2DM would not be deemed diabetic, where HbA1c was the sole diagnostic criterion. These people were older at diagnosis and more likely to be of white ethnicity. They were also more likely to have been asymptomatic at diagnosis. At recruitment, however, there was no difference in their complication status except for a higher prevalence of sensory neuropathy. One year later, although fewer were prescribed medical therapy for hyperglycemia, their HbA1c remained lower but more had an MI in the year, although the group had lower BMI, diastolic blood pressure, and triglycerides throughout and lower prevalence and development of microalbuminuria. There were no significant differences in other micro- and macrovascular complications.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has looked at the phenotypes associated with the different criteria for diagnosing T2DM. Other studies have found sole use of HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) to diagnose T2DM can alter the epidemiology of T2DM, reporting that diagnostic HbA1c misses 62–65% of people (especially asymptomatic) identified on OGTT in screening programmes [15–17].

A high proportion of participants in both of our groups, significantly greater in those with low HbA1c at diagnosis, denied osmotic symptoms at diagnosis. All diagnostic criteria require a second confirmatory biochemical test to establish the diagnosis in the absence of symptoms. Evidence of fulfilment of this requirement was absent from half the records investigated for this. Information not found in the patient or study records may have contributed to the diagnosis at the time. However, it is possible that in these participants another health event may have lowered physicians' threshold for diagnosing diabetes (reverse causality) [18]. The overrepresentation of retired people in the group may be a reflection of the slightly increased age, and/or a greater engagement with healthcare procedures, including screening. While healthcare is free at the point of delivery in the UK, cultural issues may influence uptake, although it should be noted that neither employment status nor educational attainment was different between the groups. Even with the potential for misdiagnosis of diabetes in some participants with low HbA1c at diagnosis, the lack of difference in diabetes complications suggests that opportunities for secondary prevention may be missed by widespread use of HbA1c alone to diagnose diabetes, for example, in screening programmes.

Nonglycemic cardiovascular risk factors such as BMI, lipid profile, and diastolic blood pressure were reduced in the low HbA1c at diagnosis group and prevalence of smoking was not different. Nevertheless, although absolute numbers are low, there was a higher incidence of new MI at year one (with a possible trend towards a greater positive history of MI at recruitment). Possible contributors to this occurrence may include the slightly greater age of the subjects in this group, or their different ethnicity (see below), or reverse causality, with presence of a cardiovascular risk event increasing the chance of being screened for diabetes. Sensory neuropathy was also higher at recruitment in the group with the low diagnostic HbA1c. Sensory neuropathy is less specific to diabetes than retinopathy and nephropathy, although dysglycaemia has been implicated in the pathogenesis of otherwise idiopathic neuropathy [19–22]. The higher proportion of individuals on oral hypoglycemic agents in the higher HbA1c group at recruitment and one year mirrors their average HbA1c at those times. Given the lack of difference in complication status found between T2DM participants diagnosed with HbA1c below or above the currently recommended guideline, our findings underline the importance of also applying non-HbA1c tests.

Only ethnicity, age at diagnosis, and triglyceride levels predicted diagnosis with HbA1c below 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) in multivariate analysis. Ethnicity may contribute to the differences in BMI, LDL cholesterol, and diastolic blood pressure noted at diagnosis and even to the higher development of MI in the first year after recruitment in the low diagnostic HbA1c group. The SOUL-D participants of black ethnicity still show the traditional “cardioprotective” lipid profile, but they show higher blood pressure compared to white participants [11], and they were underrepresented in the low diagnostic HbA1c group, although unexpectedly the incident MI in the study occurred in nonwhite participants. The proportion of people of black ethnicity recruited to SOUL-D precisely matches the proportion in registers of people with existing diabetes, suggesting that the SOUL-D study did pick up a representative sample of all those at risk for type 2 diagnosis and again arguing against healthcare access as a major contributor to the differences observed.

It is however likely that ethnicity itself impacts on HbA1c at presentation of diabetes [23–25]. Higher HbA1c in black people may not reflect higher plasma glucose concentrations and it has been suggested that plasma glucose might be more applicable than HbA1c for diagnosing diabetes in black people [26]. However, two large population studies have shown that retinopathy prevalence is as high for any given HbA1c and indeed may be higher than the reference category for a lower HbA1c in black populations [27, 28]. This suggests HbA1c is potentially stronger at predicting complications than plasma glucose and therefore a superior screening tool, as the main drive to diagnose asymptomatic diabetes is to engage in prevention of complications [27, 28]. Our finding of higher age at diagnosis in participants diagnosed with HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%), despite positive correlations between age and HbA1c [29, 30], may relate to the younger age at diagnosis of diabetes in nonwhite populations [13].

Limitations include the exclusion of individuals with very advanced complications and those who were housebound or not fluent English language speakers. Exclusion of those with very advanced complications may have been greater in the higher HbA1c group, although very advanced complications are not common in the newly diagnosed patients who were the target of this study. Nonfluent English language speakers might also be at higher risk for worse disease in that they may be less likely to access English language health services; however they formed only 7% potentially eligible patients [13]. The power of comparisons in biomedical data between diagnostic groups was weakened by a low number of micro- and macrovascular events in both groups. Positive aspects of the study were the large sample size and high representation of participants of black ethnicity, reflecting engagement with the specific multicultural population and their high risk for T2DM. The availability of diagnostic data, while not measured in a core laboratory, was analysed using similar assay methods and has allowed us to look at the characteristics of the subjects before intervention.

In conclusion, almost a quarter of SOUL-D study participants may not have been diagnosed with T2DM had HbA1c been introduced as the sole diagnostic tool before their diagnosis. This may be of particular importance to asymptomatic individuals, where the purpose of diagnosis is to avoid future diabetes-related complications. This study provides evidence for the consideration of ethnicity when diagnosing T2DM using HbA1c: its use may miss people of white ethnicity who have previously been diagnosed on other criteria and may change the individuals identified with or without diabetes in screening programmes, perhaps particularly in older people and those of nonblack ethnicity. While long term follow-up of the cohorts reported here will be confirmatory, our present findings so suggest that while HbA1c of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) or greater as the diagnostic marker for T2DM is useful when positive, a negative result cannot be taken as conclusive evidence to exclude the diagnosis of clinically important diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference no. RP-PG-0606-1142). The authors are grateful to all the general practitioners and their staff for the help provided in identifying and approaching patients and in making available facilities for conducting interviews. They would also like to thank their research team, past and present: J. Schonbeck, J. Valka, N. Iles, S. Brooks, J. Hunt, K. Twist, R. Stopford, G. Knight, A. Barlow, L. East, B. Jackson, E. Britneff, J. Pierre-Laake, C. Garrett, C. Mohandas, and A. Bayley. Finally, they are extremely grateful to the participants in SOUL-D without whom this study would not have been possible.

Abbreviations

- CVA:

Cerebrovascular incident

- HbA1c:

Glycated haemoglobin

- MI:

Myocardial infarction

- T2DM:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- ACR:

Albumin creatinine ratio

- BMI:

Body mass index

- OGTT:

Oral glucose tolerance test.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.The International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1327–1334. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonora E., Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with A1C. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):S184–S190. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Use of Glycated Haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Abbreviated Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCance D. R., Hanson R. L., Charles M.-A., et al. Comparison of tests for glycated haemoglobin and fasting and two hour plasma glucose concentrations as diagnostic methods for diabetes. British Medical Journal. 1994;308(6940):1323–1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6940.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelgau M. M., Thompson T. J., Herman W. H., et al. Comparison of fasting and 2-hour Glucose and HbA(1c) levels for diagnosing diabetes: diagnostic criteria and performance revisited. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(5):785–791. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyazaki M., Kubo M., Kiyohara Y., et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods for diabetes mellitus based on prevalence of retinopathy in a Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Diabetologia. 2004;47(8):1411–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1466-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colagiuri S., Lee C. M., Wong T. Y., Balkau B., Shaw J. E., Borch-Johnsen K. Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:145–150. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.OFNS. Consensus 2001, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Population+Estimates+by+Ethnic+Group.

- 10. Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. Clinical Guidance: Diagnosis of Diabetes in Adults—the use of HbA1c, 2012, http://www.londondiabetes.nhs.uk/resources/guidelines/DiagnosisofDiabetes-theuseofHbA1cv10[1].pdf.

- 11.Winkley K., Thomas S. M., Sivaprasad S., et al. The clinical characteristics at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in a multi-ethnic population: the South London Diabetes cohort (SOUL-D) Diabetologia. 2013;56(6):1272–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding S., Greenwood R., Aldington S., et al. Grading and disease management in national screening for diabetic retinopathy in England and Wales. Diabetic Medicine. 2003;20:965–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2003.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geistanger A., Arends S., Berding C., et al. Statistical methods for monitoring the relationship between the IFCC reference measurement procedure for hemoglobin A1c and the designated comparison methods in the United States, Japan, and Sweden. Clinical Chemistry. 2008;54(8):1379–1385. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.103556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X., Pang Z., Gao W., et al. Performance of an A1C and fasting capillary blood glucose test for screening newly diagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes defined by an oral glucose tolerance test in Qingdao, China. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):545–550. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P. R., Bhansali A., Ravikiran M., et al. Utility of glycated hemoglobin in diagnosing type 2 diabetes mellitus: a community-based study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;95(6):2832–2835. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carson A. P., Reynolds K., Fonseca V. A., Muntner P. Comparison of A1C and fasting glucose criteria to diagnose diabetes among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):95–97. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guideline. 130. NHS; 2011. Hyperglycaemia in acute coronary syndromes: management of hyperglycaemia in acute coronary syndromes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman-Snyder C., Smith B. E., Ross M. A., Hernandez J., Bosch E. P. Value of the oral glucose tolerance test in the evaluation of chronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63(8):1075–1079. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.8.noc50336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith A. G., Singleton J. R. The diagnostic yield of a standardized approach to idiopathic sensory-predominant neuropathy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(9):1021–1025. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singleton J. R., Smith A. G., Bromberg M. B. Increased prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance in patients with painful sensory neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1448–1453. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumner C. J., Sheth S., Griffin J. W., Cornblath D. R., Polydefkis M. The spectrum of neuropathy in diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. Neurology. 2003;60(1):108–111. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saaddine J. B., Fagot-Campagna A., Rolka D., et al. Distribution of HbA1c levels for children and young adults in the U.S.: third national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(8):1326–1330. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman W. H., Ma Y., Uwaifo G., et al. Differences in A1C by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2453–2457. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman W. H., Cohen R. M. Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose: implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(4):1067–1072. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapp-Jumbo E., Edeoga C., Wan J., Dagogo-Jack S., Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) Research Group Ethnic disparity in hemoglobin A1c levels among normoglycemic offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrine Practice. 2012;18(3):356–362. doi: 10.4158/EP11245.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsugawa Y., Mukamal K. J., Davis R. B., Taylor W. C., Wee C. C. Should the Hemoglobin A1c diagnostic cutoff differ between blacks and whites?: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(3):153–159. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bower J. K., Brancati F. L., Selvin E. No ethnic differences in the association of glycated hemoglobin with retinopathy. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005—2008. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):569–573. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilpatrick E. S., Dominiczak M. H., Small M. The effects of ageing on glycation and the interpretation of glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes. Oxford Journals. 1995;89:307–308. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson M. B., Schriger D. L. Effect of age and race/ethnicity on HbA1c levels in people without known diabetes mellitus: implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2010;87(3):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]