Abstract

Aim

To quantify in vivo the biodistribution of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and PLGA/chitosan nanoparticles (PLGA/Chi NPs) and assess if the positive charge of chitosan significantly enhances nanoparticle absorption in the GI tract.

Material & methods

PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs covalently linked to tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate (TRITC) were orally administered to F344 rats for 7 days, and the biodistribution of fluorescent NPs was analyzed in different organs.

Results

The highest amount of particles (% total dose/g) was detected for both treatments in the spleen, followed by intestine and kidney, and then by liver, lung, heart and brain, with no significant difference between PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs.

Conclusion

Only a small percentage of orally delivered NPs was detected in the analyzed organs. The positive charge conferred by chitosan was not sufficient to improve the absorption of the PLGA/Chi NPs over that of PLGA NPs.

Background

Oral administration of drugs faces several limitations including degradation under the acidic environment of the stomach and enzymatic degradation, as well as low intestinal mucosal permeability and rapid clearance of unabsorbed drugs from the GI tract [1–3]. Recently, attention has been focused on polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) as a way to efficiently deliver drugs that are susceptible to gastrointestinal degradation, or are poorly absorbed [4,5].

NP composition affects drug behavior in vivo, and hence the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of the entrapped drug. Several polymers have been extensively studied as viable materials for NP drug delivery systems. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) is a biodegradable and biocompatible polymer shown to adequately entrap and deliver hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecules [6] for improved drug bioavailability and efficacy [7]. Chitosan, an N-deacetylated derivative of chitin, is regarded as a non-toxic, biocompatible, positively charged polymer. In vitro and in vivo studies suggested that absorption of drugs can be improved by chitosan due to a combination of enhanced mucoadhesion and transient opening of tight junctions between the mucosal cells [8].

NP size, hydrophobicity and charge have been shown to play a critical role in the uptake of NPs delivered orally to mice and rats [9]. According to Primard et al. [10], NPs must be less than 200 nm to diffuse through the mucus and avoid elimination by mucilliary clearance after oral delivery. The surfactant used in the NP preparation affects the size and hydrophobicity [11], thereby affecting NP uptake [12]. Particles that are less hydrophilic are more readily absorbed than those covered with poly(vinylalcohol) (PVA), suggesting that surface hydrophobicity plays a major role in the uptake of orally delivered particles [11]. Positively charged chitosan particles are trapped within the negatively charged mucin layer immediately adjacent to the intestinal epithelium, leading to increased epithelial contact time and thereby increasing absorption of the entrapped drug [13,14].

NP tracking during their transit from the GI tract to major organs is most commonly measured by radioactive labeling [15,16], or fluorescent labeling with FITC [4], rhodamine, coumarin [17] or rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RBITC) [18]. Biodistribution results are reported either as percentage fluorescence or percentage radioactivity detected in different organs at a certain time point relative to total fluorescence/radioactivity at that time, as percentage dose relative to the total administered dose, or as percentage dose per gram tissue at each time point. Other authors had expressed the results as percentage particles detected in tissue [19]. These differences in reporting must be considered when comparing the literature on NP uptake and biodistribution [20]. In addition, most of the in vivo studies test the NPs biodistribution after administration of a single dose of NPs. There is a paucity of literature in which NP distribution was quantified following a repeat-dose exposure, particularly oral exposure. Most in vivo biodistribution data is reported for NPs delivered intravenously. When the intravenous route is used, the liver concentrates the highest percentage of dose after 24 h [15], but when NPs are orally administered, results can vary depending of the nature of the NPs [11].

The aim of this study was to quantify biodistribution of PLGA and PLGA NPs covered with a layer of chitosan (PLGA/Chi) of similar sizes and surfactant concentrations, and to test whether the presence of positively charged chitosan significantly improved the gastrointestinal uptake of the NPs. It was hypothesized that PLGA/Chi NPs will have better absorption through the gut due to their charge, but once absorbed, relative distribution within rat tissues compared with neutral charged NPs (PLGA) would be similar. Tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate (TRITC) covalently labeled PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs were synthesized to allow for the NPs to be traced in each tissue via fluorescence. After daily oral administration of 3 mg NPs for 7 days to F344 rats, a comparison between the biodistribution of PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs in various tissues, including intestine, liver, spleen, kidney, lung and brain, was performed.

Materials & methods

Materials

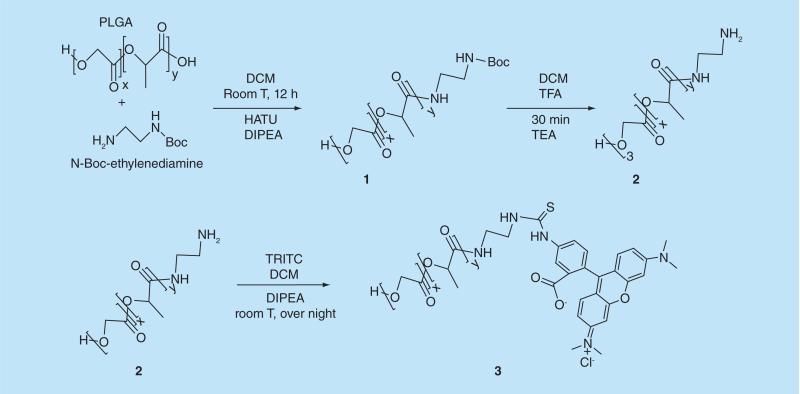

Synthesis of TRITC-labeled PLGA

The attachment of TRITC to PLGA was performed by uranium salt chemistry [21,22]. Briefly, 1 g of poly (d, l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) was dissolved in 20 ml of DCM at room temperature (Figure 1). Next, 52.5 mg of HATU, 23.4 mg of N-Boc-ethylenediamine, and 0.20 ml of DIPEA was added. The suspension was stirred for 12 h at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of 100 ml of distilled water. Next, the organic solution was poured in 150 ml of ethanol to obtain a white precipitate (1) that was collected by filtration. The washing protocol was repeated twice, and the final solids were dried under high vacuum overnight. Next, a deprotection step was performed on the 800 mg solids recovered from the previous step by re-suspending the intermediate product in 10 ml of DCM, followed by the addition of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (1:1 DMC:TFA v/v). The reaction was carried out for 35 min at room temperature under mild stirring. Next, the solution was added drop-wise to 100 ml of ethanol. The precipitated polymer (2) was dried under high vacuum overnight. The solids were suspended in 10 ml of DCM, and 1 ml of triethanolamine (TEA) was added for neutralization. The mixture was added drop-wise to 100 ml of ethanol, and the white precipitate was dried again under high vacuum overnight. The final step was the conjugation of PLGA amine to TRITC, which was performed by dissolution of PLGA-amine polymer (700 mg) in 20 ml of DCM and 0.065 ml of DIPEA. After 10 min of mixing at room temperature, 20 mg of TRITC was added. The reaction was carried out under stirring overnight at room temperature under dark conditions. The organic phase was washed with water six to nine times in a separation funnel. The organic phase was poured into 100 ml of ethanol to obtain a dark pink solid precipitate. The solids (3) were collected by filtration and re-suspended in 20 ml of DCM for another ethanol precipitation step. Finally, the solids were dried under high vacuum for 30 h and kept at −20°C for further characterization and use in polymeric NP synthesis.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid-tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate to be used in the nanpparticle synthesis.

PLGA, PLGA-TRITC & PLGA/Chi NP synthesis

The polymeric NPs were synthesized by emulsion evaporation technique [23,24]. The organic phase was formed by ethyl acetate (10 ml) with dissolved PLGA (200 mg) and PLGA conjugated with TRITC (300 mg). Next, 80 ml of the aqueous phase with polyvinyl alcohol (2% w/v) was saturated with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was poured into the aqueous phase and mixed for 10 min at room temperature. The emulsion was microfluidized (Microfluidics, Newton, MA, USA) at 30,000 Psi. Next, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum for 1 h with a rotoevaporator (Buchi Corporation, New Castle, DE, USA). The purification was performed by dialysis (molecular weight cut-off 100,000 g/mol) with regenerated cellulose membranes (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) for 2 days. For PLGA/Chi NP synthesis a chitosan solution (5% of the initial mass of PLGA) at pH 5 was added to PLGA NPs suspension following dialysis, and the final suspension was stirred for 15 min at room temperature. The ionic interactions between the negative charge of PLGA carboxylic acid end groups and the positive amine groups of chitosan allowed a layer formation at the interface of the polymeric NPs. Finally, trehalose (1:1 w/w) was added as cryoprotectant to the NP suspension before freezing the sample. A Freeze drier (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) was used to dry the polymeric NPs for 2 days. The final powder was stored at 4°C for characterization and animal studies.

Residual PVA measurement

The colorimetric method used to quantify residual PVA on the surface of the NPs was based on the reaction of iodine and the hydroxyl groups of PVA [25]. Briefly, the sample was dissolved in 2 ml of NaOH (1 N) and heated to 60°C for 15 min, followed by a pH adjustment with 0.9 ml of 1 N HCl and 2.1 ml of distilled water. Next, 3 ml of boric acid (0.65 M), and 0.5 ml of iodine/KI solution (0.05 M/0.15 M) were added. The final volume was adjusted to 10 ml with distilled water. Finally, after 15 min at room temperature, the samples were read at 690 nm with a spectrophotometer (Genesis 6, Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC, USA). The standard curve was prepared with the same protocol using different PVA concentrations (2–20 μg/ml).

Characterization of fluorescent NPs

Size measurements of particles & ζ potential

Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS was used (Malvern Instrument Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) to measure NP size, size distribution and ζ potential. ζ potential was measured in 10 mM NaCl at different pHs; a concentration of 100 μg/ml of particle powder was used for size and ζ potential measurements.

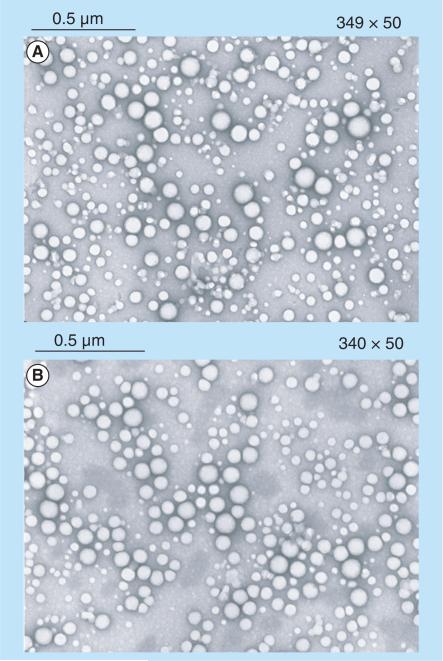

Morphology

Transmission electron microscopy pictures were taken with a JEOL 100-CX (Jeol USA Inc., Peabody, MA, USA). The NP powder was re-suspended in water, and a sample droplet was placed on a carbon grid and uracyl acetate (2%) added as contrast agent. The excess was removed with a filter paper and the sample was dried for 10 to 15 min at room temperature before placing the grid in the transmission electron microscope.

In vivo biodistribution of fluorescently labeled PLGA & PLGA/Chi NPs

Animals

Male F344 rats (200–300 g) were used for the in vivo biodistribution studies. Animals used in the experiment were all maintained, treated and housed according to the guidelines of the Louisiana State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were acclimated for 1 week before the treatment, and randomly divided into groups of two rats per cage. The animals were gavaged once daily for 7 days with a dose of 3mg/ml of PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs, respectively (~12 mg/kg, depending on the weight of the animal). All rats were fasted for 12 h before the gavage, but allowed free access to water. Two different NPs were used as treatments: PLGA NPs and PLGA/Chitosan NPs, both fluorescently tagged. NPs were suspended in Phosphate Buffer Saline (pH 7.4) prior to gavage. Each treatment was orally administered to four rats (1 ml of suspended NPs/rat). Three similarly housed but untreated rats (without polymeric NPs) were used as a control. The same control rats were euthanized after quarantine and the tissues were used to prepare the fluorescent standard curves used to detect NPs in the treated animals.

Tissue collection

After 7 days of daily gavage the animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. Euthanasia was performed 24 h after the last gavage. Gross necropsies were performed, and heart, spleen, kidney, liver, intestine and brain were excised for further analysis. The samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Biodistribution analysis

Four rats per type of particles were used to measure NP biodistribution. The tissues were homogenized in PBS, using an IKA ULTRA-TURRAX homogenizer model T18 basic (IKA® Works Inc., Wilmington, NC, USA), and then completely digested in 1 N NaOH following a procedure adapted from Yin et al. [4]. After centrifugation at 7155 g for 10 min at room temperature, 100 μl of the supernatant was loaded in triplicate in black 96 wells plate with clear bottom, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using a Perkin Elmer Wallac 1420 multilabel counter (software version 3.0) (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). To set up the calibration curves, increasing amounts of fluorescent NPs were added to each tissue type recovered from the control animals. Following digestion, the samples were centrifuged, and the fluorescence intensity measured as previously described. The standard curves were developed separately for each tissue (R2 of 0.99 for standard curves developed for tested tissues). A known amount of tissue was collected from three control animals and an increased amount of NPs was added to each tissue, separately. Every sample was read in triplicate and the corresponding plots included the nine measurements, per each concentration (three replicates collected in tissues from three animals) at five concentrations. The amount of NPs distributed in each tissue was calculated based on the standard curves and expressed as percentage total dose per gram tissue. The percentage of dose in every tissue was calculated by dividing the NP concentration (mg/ml) obtained from the standard curves at the fluorescence measured in the sample to the total administered NP dose.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed in SAS (Cary, NC, USA). Anova PROC MIXED procedure with Tukey adjustment and the macro by Arnold Saxton was used for post hoc adjustment to detect differences between treatments. A significant difference was declared at p values <0.05. The data presented residuals with a normal distribution (p > 0.05); homogeneity and independence was confirmed.

Results

Particle characterization

PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs measured in average 112 and 134 nm in diameter (Table 1), respectively. Polydispersity index (PDI) indicated that PLGA NPs (PDI of 0.112) were more tightly distributed than PLGA/Chi NPs (PDI of 0.25). The amount of PVA present on the surface of the particles was maintained at equal values between the two types of particles tested, at 23–24%. PLGA NPs were negatively charged (ζ potential of −2.1 mV), whereas PLGA/Chi NPs were positively charged (ζ potential >0 mV) up to pH 8.5 in the presence of 10 mM NaCl. All particles were spherical in shape and showed little agglomeration (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Polymeric nanoparticle characteristics.

| Diameter (nm) | PDI | ζ (mV) | PVA (%)† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | 112 ± 9 | 0.112 ± 0.017 | − 2.1 ± 0.8 | 23.7 ± 1.2 |

| PLGA/Chi | 134 ± 8 | 0.250 ± 0.058 | + 4.9 ± 2.0 | 24 ± 1.5 |

The PVA (%) was estimated relative to the initial amount used in the polymeric nanoparticles synthesis. n = 3 for all measurements.

PDI: Polydispersity index; PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; PLGA/Chi: PLGA/chitosan.

Figure 2. Transmission electron microscope picture showing the spherical morphology of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/chitosan nanoparticles.

(A) Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid and (B) poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/chitosan.

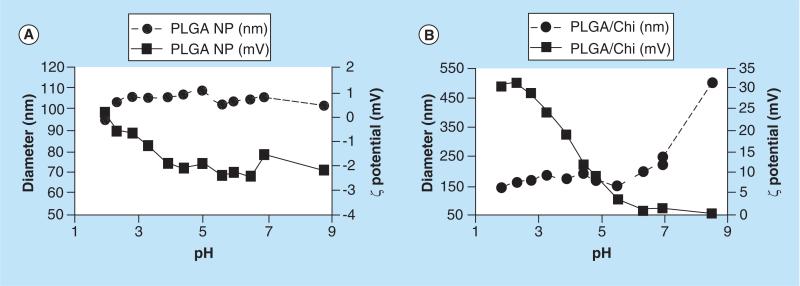

The pH titration data showed that PLGA NPs were stable in the pH range tested (1.8 to 8.7) with uniform particle diameter (100–110 nm) and negative ζ potential (0 ± 3 mV; Figure 3). PLGA/Chi NPs measured 140–150 nm at pHs ≤6, followed by an increase in the particle diameters at higher pH (480 nm at pH 8.7). ζ potential of PLGA/Chi NPs constantly decreased from 33 mV at pH 2 to 1 mV at pH 8.7.

Figure 3. Size and ζ potential change of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/chitosan nanoparticles as a function of pH.

(A) PLGA nanoparticles and (B) PLGA/Chi nanoparticles, indicating that PLGA NPs maintained a stable size (~100 nm) and ζ potential [0, −2 mV] over the pHs tested, whereas PLGA/Chi NPs increased in size from 150 nm to over 450 nm with a change of ζ potential from 31 mV at acidic pHs to 0.5 mV at neutral pHs specific to the intestinal media.

NP: Nanoparticle; PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; PLGA/Chi: PLGA/chitosan.

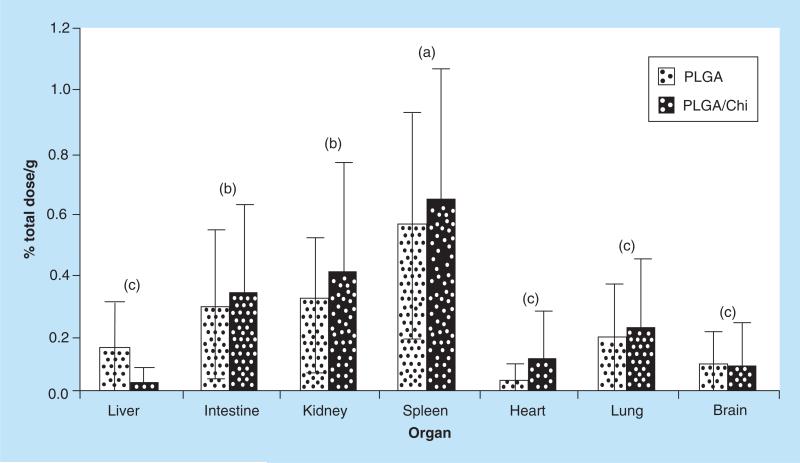

In vivo biodistribution of NPs

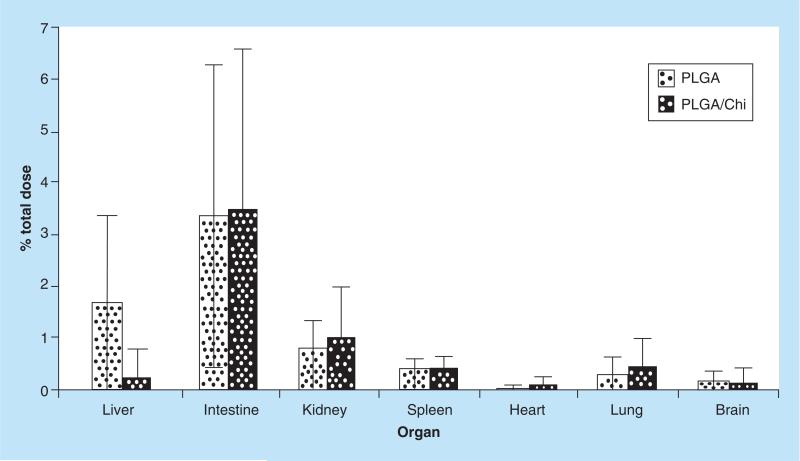

Biodistribution of fluorescent NP in each tissue was determined based on the established standard curves, and the results were expressed as percentage dose per gram tissue tissue to compensate for possible variations between animals. The percentages were calculated relative to the total dose (21 mg of NPs over a 7 day period) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. In vivo biodistribution of fluorescent nanoparticles.

The amount of fluorescent nanoparticle in each organ was determined on the basis of standard curves; the results were expressed as % total dose/g tissue. (a–c) depict statistically significant differences between organs for each treatment (p < 0.05). When PLGA and PLGA/Chi nanoparticle treatments were compared, no statistical difference was found (p > 0.05).

PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; PLGA/Chi: PLGA/chitosan.

The relative NP biodistribution in various organs indicated that the highest amount of PLGA NPs concentrated in the spleen (0.6% total dose/g), followed by kidney (0.3% total dose/g), intestine (0.28% total dose/g), lung (0.17% total dose/g), liver (0.14% total dose/g), brain (0.08% total dose/g) and heart (0.03% total dose/g). The concentration of PLGA/Chi NPs recovered in tested tissue was the following: spleen (0.63% total dose/g), kidney (0.39% total dose/g), intestine (0.32% total dose/g), lung (0.21% total dose/g), heart (0.10% total dose/g), brain (0.08% total dose/g) and liver (0.02% total dose/g). For both PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs, the biodistribution of NPs showed three statistically different groups: the highest represented by the spleen, followed by intestine and kidney, and then by lung, brain, heart and liver (Figure 4). Statistically, the difference between PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs was not significant.

The percentage NPs recovered in each organ was calculated by multiplying the percentage of daily or total dose per gram of tissue with the individual organ weight recorded for each individual animal. Overall, 6.6% PLGA and 5.9% PLGA/Chi of total dose were recovered after 7 days of daily gavage with 3 mg NPs/dose in the tissue processed (Figure 5). The percentage of the total PLGA NP dose recovered was highest in the intestine (3.34%) and was followed by the liver (1.63%), kidney (0.79%), spleen (0.36%), lung (0.29%), brain (0.15%) and heart (0.03%). The percentage of total PLGA/Chi NP dose demonstrated a similar distribution (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage of total dose of fluorescent poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/chitosan nanoparticles recovered in each analyzed organ.

The highest dose of the orally delivered treatments was detected in the intestine for both PLGA and PLGA/Chi nanoparticles, with no significant difference between the two treatments.

PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; PLGA/Chi: PLGA/chitosan.

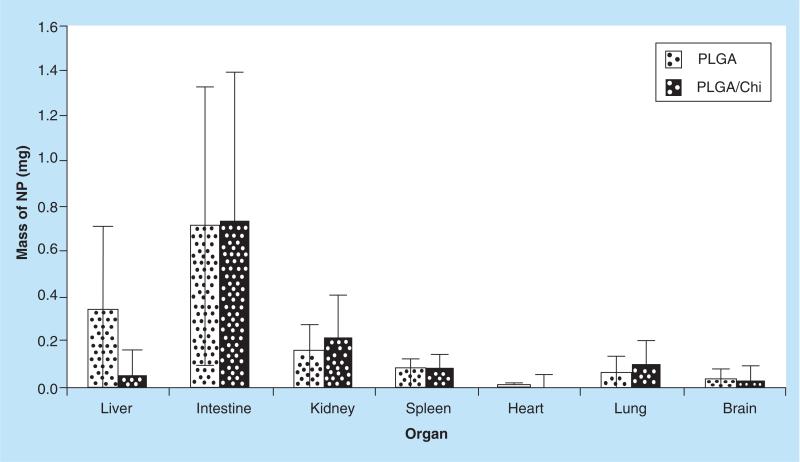

The total mass of NPs recovered (mg) at the end of the study in the assessed organs was approximately 1.38 mg for PLGA and 1.23 mg for PLGA/Chi of the total 21 mg administered over the 7-day study. Intestine showed the highest amount of recovered particles in comparison with the other organs, which is not surprising for an oral delivery system, but no significant difference was found between PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Mass of PLGA and PLGA-Chi (mg) nanoparticles recovered in the organs tested (liver, intestine, kidney, spleen, heart, lung and bran) after gavage daily for 7 days.

The total mass of NPs recovered was 1.38 mg for PLGA NPs and 1.23 mg PLGA/Chi NPs out of the 21 mg NPs orally administered by daily gavage of 3 mg NPs to the F344 rats over 7 days.

NP: Nanoparticle; PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; PLGA/Chi: PLGA/chitosan.

Discussion

In this study, PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs were investigated to determine the effect of NP charge on uptake and biodistribution of NPs orally delivered to rats in a repeat-dose study. PLGA used in the NPs synthesis was covalently linked to a fluorescent dye (TRITC), which allowed NP tracking and quantification in all organs of interest. Particles tested were similar in size (112 nm vs. 134 nm in diameter for PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs), and had a similar amount of surfactant on the surface (24%). ζ potential of PLGA NPs was slightly negative (−1.5 mV), whereas PLGA/Chi NPs had a slight positive ζ potential ranging from of +1.8 mV to +4.9 mV in presence of 10 mM NaCl measured by titration (Figure 2) or by capillary cell (Table 1) at neutral pH.

Even though nanoparticle absorption was expected to be improved for the positively charged particles, PLGA/Chi results showed a small increment in uptake compared with PLGA NPs after 7 days of daily gavage with no statistically difference between the two types of NPs. Chitosan is strongly charged at acidic pHs due to the protonation of the amine groups [14]. If protonated, the strong positive charge of chitosan promotes ionic interaction between the NPs and the mucus in the gut (i.e., mucin has negatively charged carboxylic end groups at neutral pHs) [26]. The electrostatic interaction between negatively charged mucus and positively charged PLGA/Chi NPs would extend the retention time of NPs in the gut [27] and as a result improve NP absorption [13]. The small improvement observed in polymeric NP translocation when covered with a layer of chitosan (Figure 6) was most likely due to the charge screening effect of the polymeric surfactant, PVA present on the NP surface. PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs ζ potentials albeit one negative (−1.5 mV) and the other positive (+1.8 mV), were very close to neutral under the pHs representative of the intestine (Figure 3), resulting in no significant difference between the systems in terms of NP uptake. The overall recovery of polymeric NPs after 7 days of daily gavage was around 6.6% for PLGA NPs and 5.9% for PLGA/Chi NPs of the total gavaged dose of 21 mg. Since metabolism and excretion of absorbed NPs was occurring throughout the study, the 1.4 mg recovered at the endpoint likely represents the steady state concentration of particles. The low absorption for an orally administered NP treatment was not surprising. Other studies of PLGA NP translocation in animal models have shown high excretion of NPs. For example, Le Ray and coworkers [15] measured the percentage of radioactive NPs in feces and urine after 24 h of oral administration of NPs and found them to be equal to 65.5 ± 32.5% and 0.3 ± 0.2%, respectively. Similar results were found by Loeschner study [28] that showed Ag NP recovered in feces and urine was 63 ± 23% and 0.005 ± 0.003%, respectively.

For all orally delivered NPs, it is expected that a high percentage of the NPs would be detected in the intestine. It has been shown that the highest percentage of 146 ± 10.1 nm covalently linked FITC-PLGA NPs and 239 ± 13.6 nm PLGA conjugated to wheat germ agglutinin WGA-PLGA NPs were found in the intestine following gavage of rats for 7 days [4]. Florence and Hussain [29] reported that transit time from the stomach to the colon in normal rat gut was 24 h. Using I125 labeled PLGA NPs (200 nm), they showed that at 4 h, 30% of the total dose was in the small intestine, and at 8 h around 40% of total dose was in caecum. Quini et al. [30] compared the transit time of liquid and solid meals in rats using a non-invasive magnetic method and found that 7 h after feeding the gastric section was completely empty of solid meal. In the present study, samples were collected 24 h after the last dose was administered, and we expected that some of the NPs had already passed in the feces, while others were either in tissue or in circulation, hence the relatively low amount of particles detected in the intestine. When compared with other tissues of interest, the presence of particles in the intestine (3.5%) was higher than in other organs, with liver, kidney and spleen following closely.

The administration, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) process of intravenous and oral delivery NPs had been discussed in the literature [31,32]. The distribution of NPs has been shown to be affected by the size, shape, surface charge and mechanical properties [33,34]. In comparison, NPs orally administered need to pass several barriers on their way to systemic circulation, such as the acidic pH in the stomach, proteases in the gut lumen and brush border membrane, tight junctions between enterocytes and metabolism by liver enzymes [33], and mucus barrier along GI tract [35]. Orally administered NPs cross the intestinal epithelial cells primarily by transcytosis [33]. Once endocytosed, NPs present in the lamina propria have the option of being transported to distant tissues via blood or the lymphatics [36]. Typically, water soluble substances move quickly into the vasculature while lipophilic compounds move into and through the lymphatics prior to entering the circulation [36–38]. Based on the fact that polymeric NPs tested in this study were water soluble, they probably followed the blood vascular route from the intestine to the other target organs tested.

In this study, the reported biodistribution of NPs of different surface properties showed the highest percentage total dose of NP/g recovered in the spleen (0.56% per gram PLGA – 0.63% per gram PLGA/Chi). Similar high uptake of NPs by the spleen was previously reported [39], for orally administered fullerene for 7 consecutive days (daily dose of 1.7 mg/kg body weight). The spleen is a secondary lymphoid organ present in all the vertebrates and has three main functions. First, T- and B-lymphocytes in the splenic white pulp rapidly produce immune-mediated responses to antigens carried by the blood. Second, the splenic red pulp has a filtering function for the blood (material can be phagocytized by macrophages) and third, in some mammalian species it can be a reservoir of red blood cells [40]. When the NPs reach the systemic circulation, the particles can potentially interact with plasma proteins, coagulation factors, and blood cells [32]. It is plausible that circulating NPs interacted with plasma proteins or cellular blood components and were removed from the systemic circulation by the resident macrophage population in the spleen, leading to the high splenic concentration of particles.

Kidneys had the second highest concentration (0.4% total dose/g) for both types of NPs (PLGA and PLGA/Chi). Renal clearance of intravascular agents is a multifaceted process involving glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and finally elimination of the molecule through urinary excretion. As intravascular agents enter the glomeruli, molecules are either filtered through the glomerular capillary wall and into the proximal tube, or remain within the vascular compartment [41]. Due to the possibility that intact particles or small parts of the fluorescently-tagged NPs might have been dislocated during the process of NP degradation, their presence in the kidney was not surprising.

The hepatobiliary system represents the primary route of excretion for particles that do not undergo renal clearance. The liver provides the critical function of catabolism and biliary excretion of bloodborne particles as well as serves as an important site for the elimination of foreign substances and particles through phagocytosis. The liver is a large organ and therefore the recovered NP dose (% dose/g tissue) appeared small, but when compared with the other smaller organs the overall amount of particles in the liver (mg) was in fact significant.

The lung recovered only 0.17% and 0.21% of total dose/g of PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs, respectively, as a result of the uptake of the NPs that entered the blood circulation into the lungs. The brain and heart reported less than 0.1% per gram each of the total percentage of dose of administered NPs. The small NP concentration in the heart was expected considering that the heart is not as highly perfused (on a ml or volume basis) when compared with the other larger organs (liver, intestines, spleen), and it is not a filter organ like the liver, kidney, and spleen. The small NP uptake by the brain indicated that very small amounts of NPs if any make it through the blood–brain barrier.

Conclusion

The small positive charge of chitosan was not sufficient to significantly increase the absorption of the charged NPs. After seven days of repeated daily gavage no significant difference in absorption was found between PLGA and PLGA/Chi NPs, mostly due to the charge-shielding effect of the polymeric surfactant used on the surface of the particles. NP biodistribution data indicated that the spleen had the highest concentration of NPs when expressed as percentage dose per gram tissue, whereas the intestine packed the highest amount of particles, followed by the liver when the concentration was expressed as percentage dose. The total amount of particles recovered after seven days was less than 1.5 mg of the 3 mg NPs administered daily for 7 days (for a total of 21 mg), so most particles were either not absorbed, circulating in the blood or were excreted from the system indicating that bioaccumulation was not occurring to any significant degree. Additional studies are needed to determine the percentage absorption and the half-life of the NPs.

Future perspective

Just as with any other oral delivery system, polymeric NPs need to be meticulously studied to understand their potential for different drug delivery applications. Due to the enormous number of options for polymers, surfactants, and drugs, the task of assessing biodistribution, metabolism and excretion of all individual nanodelivery systems is tremendous. The in vivo study conducted herein is simply the first step in identifying the ADME process for the types of NPs tested. With knowledge on biodistribution of NPs and their overall intestinal uptake, the effect of the NP presence in various organs on the function of the organ and overall toxicity of the nanodelivery systems must be studied. Acute and repeat-dose studies are necessary to deem NPs safe to use as oral delivery systems.

Key terms.

Polymeric nanoparticles: Nanoparticles made of polymers measuring between 1 and 100 nm in diameter.

Biodistribution: Method of tracking where compounds of interest travel in an experimental animal or human subject.

Gavage: The administration of food or drugs, especially to an animal, typically through a tube leading down the throat to the stomach.

Key term.

Fluorescence: The property of absorbing light of short wavelength, such as ultraviolet light, and emitting light of longer wavelength.

Key term.

GI tract: Organ system responsible for consuming and digesting foodstuffs, absorbing nutrients, and expelling waste, commonly defined as the stomach and intestine.

Executive summary.

Nanoparticles characterization

The low positive charge of chitosan was not sufficient to increase the absorption of the nanoparticles (NPs) through the intestinal epithelia. ζ potential of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (negative) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/chitosan NPs (positive) were both very close to neutral at pH 7.

In vivo biodistribution

The highest NP presence was detected in the spleen (% dose/g tissue) and the greatest mass of NPs was found in the intestine (mg).

Of the total dose of NPs orally administered (21 mg) over a period of 7 days, the recovered amount was only 1.5 mg. Most NPs were excreted or were still in circulation at the time of sampling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Increasing Scientific Data on the Fate, Transport and Behavior of Engineered Nanomaterials in Selected Environmental and Biological Matrices funding program administered jointly by the Environmental Protection Agency, National Science Foundation, and US Department of Agriculture, EPA-G2010-STAR-N2 Food Matrices Award # 2010–05269.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

- 1.Mahato RI, Narang AS, Thoma L, Miller DD. Emerging trends in oral delivery of peptide and protein drugs. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2003;20(2–3):153–214. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v20.i23.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson CJ, Tetley L, Cheng WP. The influence of polymer architecture on the protective effect of novel comb shaped amphiphilic poly(allylamine) against in vitro enzymatic degradation of insulin – towards oral insulin delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;383(1–2):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen WC. Oral peptide and protein delivery: unfulfilled promises? Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8(14):607–608. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin YS, Chen DW, Qiao MX, Wei XY, Hu HY. Lectinconjugated PLGA nanoparticles loaded with thymopentin: Ex vivo bioadhesion and in vivo biodistribution. J. Control. Release. 2007;123(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai JD, Nagai T, Wang XQ, et al. pH-sensitive nanoparticles for improving the oral bioavailability of cyclosporine A. Int. J. Pharm. 2004;280(1–2):229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain RA. The manufacturing techniques of various drug loaded biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) devices. Biomaterials. 2000;21(23):2475–2490. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, et al. PLGA-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications. J. Control. Release. 2012;161(2):505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Wood E, Dornish M. Effect of chitosan on epithelial cell tight junctions. Pharm. Res. 2004;21(1):43–49. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000012150.60180.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohanraj VJ, Chen Y. Nanoparticles - A review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2006;5(1):561–573. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Primard C, Rochereau N, Luciani E, et al. Traffic of poly(lactic acid) nanoparticulate vaccine vehicle from intestinal mucus to sub-epithelial immune competent cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31(23):6060–6068. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma G, Van Der Walle CF, Kumar MNVR. Antacid co-encapsulated polyester nanoparticles for peroral delivery of insulin: Development, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and pharmacodynamics. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;440(1):99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peetla C, Labhasetwar V. Effect of molecular structure of cationic surfactants on biophysical interactions of surfactantmodified nanoparticles with a model membrane and cellular uptake. Langmuir. 2009;25(4):2369–2377. doi: 10.1021/la803361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagpal K, Singh SK, Mishra DN. Chitosan nanoparticles: a promising system in novel drug delivery. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010;58(11):1423–1430. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plapied L, Duhem N, Des Rieux A, Preat V. Fate of polymeric nanocarriers for oral drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;16(3):228–237. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leray AM, Vert M, Gautier JC, Benoit JP. Fate of [C- 14] Poly(Dl-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) nanoparticles after intravenous and oral-administration to mice. Int. J. Pharm. 1994;106(3):201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonaje K, Lin KJ, Wey SP, et al. Biodistribution, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of insulin analogues in a rat model: oral delivery using pH-responsive nanoparticles vs. subcutaneous injection. Biomaterials. 2010;31(26):6849–6858. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semete B, Booysen LIJ, Kalombo L, et al. In vivo uptake and acute immune response to orally administered chitosan and PEG coated PLGA nanoparticles. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;249(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esmaeili F, Ghahremani MH, Esmaeili B, et al. PLGA nanoparticles of different surface properties: Preparation and evaluation of their body distribution. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;349(1–2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semete B, Booysen L, Kalombo L, et al. Effects of protein binding on the biodistribution of PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles post oral administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2012;424(1–2):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon L, Sabliov C. Time Analysis of poly(lactic-coglycolic) acid nanoparticle uptake by major organs following acute intravenous and oral administration in mice and rats Ind. Biotechnol. 2013;9(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu S, Harfouche R, Soni S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated targeting of MAPK signaling predisposes tumor to chemotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(19):7957–7961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902857106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpino LA, Elfaham A, Albericio F. Efficiency in peptide coupling - 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole vs 3,4-dihydro-3-hydroxy-4-oxo-1,2,3-benzotriazine. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60(11):3561–3564. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Astete CE, Sabliov CM. Synthesis and characterization of PLGA nanoparticles. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2006;17(3):247–289. doi: 10.1163/156856206775997322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigoneanu IG, Astete CE, Sabliov CM. Nanoparticles with entrapped alpha-tocopherol: synthesis, characterization, and controlled release. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(10):105606. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/10/105606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahoo SK, Panyam J, Prabha S, Labhasetwar V. Residual polyvinyl alcohol associated with poly (d, l-lactide-coglycolide) nanoparticles affects their physical properties and cellular uptake. J. Control. Release. 2002;82(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai SK, Wang YY, Hanes J. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61(2):158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang JJ, Zeng ZW, Xiao RZ, et al. Recent advances of chitosan nanoparticles as drug carriers. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:765–774. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S17296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loeschner K, Hadrup N, Qvortrup K, et al. Distribution of silver in rats following 28 days of repeated oral exposure to silver nanoparticles or silver acetate. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Florence AT, Hussain N. Transcytosis of nanoparticle and dendrimer delivery systems: evolving vistas. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;50:S69–S89. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quini CC, Americo M, Cora LA, et al. Employment of a noninvasive magnetic method for evaluation of gastrointestinal transit in rats. J. Biol. Eng. 2012;6:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Andresen TL. Factors controlling nanoparticle pharmacokinetics: an integrated analysis and perspective. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012;52:481–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagens WI, Oomen AG, De Jong WH, Cassee FR, Sips AJ. What do we (need to) know about the kinetic properties of nanoparticles in the body? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007;49(3):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markovsky E, Baabur-Cohen H, Eldar-Boock A, et al. Administration, distribution, metabolism and elimination of polymer therapeutics. J. Control. Release. 2012;161(2):446–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiriyama A, Iga K, Shibata N. Availability of polymeric nanoparticles for specific enhanced and targeted drug delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2013;4(10):1261–1278. doi: 10.4155/tde.13.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ensign LM, Cone R, Hanes J. Oral drug delivery with polymeric nanoparticles: The gastrointestinal mucus barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64(6):557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desesso JM, Jacobson CF. Anatomical and physiological parameters affecting gastrointestinal absorption in humans and rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2001;39(3):209–228. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kararli TT. Gastrointestinal Absorption of Drugs. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug. 1989;6(1):39–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth WL, Freeman RA, Wilson AGE. A physiologically-based model for gastrointestinal absorption and excretion of chemicals carried by lipids. Risk Anal. 1993;13(5):531–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baati T, Bourasset F, Gharbi N, et al. The prolongation of the lifespan of rats by repeated oral administration of [60] fullerene. Biomaterials. 2012;33(19):4936–4946. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiniger B. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Wiley; NJ, USA: 2006. Spleen. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longmire M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine. 2008;3(5):703–717. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]