Abstract

Obesity has been on the rise in the United States over the past three decades, and is high. In addition to population-wide trends, it is clear that obesity affects some groups more than others and can be associated with age, income, education, gender, race and ethnicity, and geographic region. To reverse the obesity epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) promotes evidence-based and practice-informed strategies to address nutrition and physical activity environments and behaviors. These public health strategies require translation into actionable approaches that can be implemented by state and local entities to address disparities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used findings from an expert panel meeting to guide the development and dissemination of the Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities (available at http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/toolkit.html). The Toolkit helps public health practitioners take a systematic approach to program planning using a health equity lens. The Toolkit provides a six-step process for planning, implementing, and evaluating strategies to address obesity disparities. Each section contains (a) a basic description of the steps of the process and suggested evidence-informed actions to help address obesity disparities, (b) practical tools for carrying out activities to help reduce obesity disparities, and (c) a “real-world” case study of a successful state-level effort to address obesity with a focus on health equity that is particularly relevant to the content in that section. Hyperlinks to additional resources are included throughout.

Keywords: health disparities, obesity, chronic disease, health promotion, nutrition, physical activity/exercise

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has been on the rise in the United States over the past several decades, and is high. In 1990, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data indicated that no state had an obesity prevalence exceeding the Healthy People 2010 goal of less than or equal to 15% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Currently, obesity prevalence in all 50 states is greater than or equal to 20%, while obesity prevalence in 12 states is greater than or equal to 30%. This represents a national landscape where more than one third of adults (35.7%) and 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity prevalence among children and adolescents has almost tripled since 1980 (Ogden & Carroll, 2010).

In addition to these population-wide trends, it is clear that obesity affects some groups more than others and can be associated with age, income, education, gender, race and ethnicity, and geographic region. For example, data from 1999–2000 through 2009–2010 found Mexican Americans significantly more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic Whites, and non-Hispanic Black girls were significantly more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic White girls (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012).

In response to the growing prevalence of obesity in the United States, the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity (DNPAO) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working to reduce obesity and its related health conditions via a multipronged approach including active identification of promising programs and providing guidance and resources designed to prevent obesity. Priority is being given to those programs targeting improved eating habits and physical activity levels in communities experiencing health inequity (CDC, 2009). Throughout the Toolkit the term health equity refers to the attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Using a health equity lens refers to addressing particular types of health differences that are closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantages: for example, how obesity can be either facilitated or prevented by the “built environment,” which is (a) the availability and accessibility of food and drink and (b) the safety, accessibility, and existence of space for physical activity (Huang, Drewnowski, Kumanyika, & Glass, 2009). A specific example could be the following: Food desert is a term used to describe an area that has few supermarkets, and food swamp is a term some have used to describe an area with an abundance of fast-food restaurants and convenience stores. Food deserts and food swamps are associated with reduced healthy food intake and increased community obesity rates (Boone-Heinonen et al., 2011; Fielding & Simon, 2011). The built environment is in turn affected by economics—those in poorer communities often have limited access to affordable healthy foods and water but have ample access to affordable, energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and drinks, such as sugar drinks (Huang et al., 2009).

BACKGROUND

To reverse the obesity epidemic, CDC promotes evidence-based and practice-informed strategies to address nutrition and physical activity environments and behaviors. These public health strategies need to be translated into actionable approaches that can be implemented by state and local entities. In addition to seeking to address obesity in the general U.S. population, strategies must also target those experiencing the greatest disease burden. To provide health practitioners with a systematic approach to program planning using a health equity lens, CDC (2012) developed the Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities. The purpose of this article is to describe (a) the process used to develop the Toolkit, (b) the content and structure of the Toolkit, and (c) a web-based resource recently developed to help practitioners use the Toolkit.

The Toolkit was developed using input from three sources: (a) an expert panel, (b) a review of existing planning and change models, (c) states and communities who provided information used in case studies. Specific details are provided below.

Expert Panel

To facilitate the development of the Toolkit, CDC’s DNPAO convened an expert panel in May, 2011. The panel’s objectives were to (a) discuss known data and identify gaps to build a common knowledge base on health disparities related to nutrition, physical activity, and obesity; (b) recommend methodologies, tools, and resources for the integration of environmental approaches to improve diet, increase physical activity, and reduce obesity-related health disparities; and (c) define a process by which system and environmental approaches can be applied to nutrition, physical activity, and obesity-related health disparities. Eighteen experts in the fields of health disparities, nutrition, physical activity, and/or obesity prevention, along with select CDC staff, gathered to discuss strategies and approaches to inform the development of the Toolkit. Panel participants focused on three strategies that were selected by Division subject matter experts that were evidence informed and based on Division priorities:

Increasing access to fruits and vegetables via healthy food retail with a focus on underserved communities

Engaging in physical activity by increasing opportunities for walking with a focus on the disabled community and on other subpopulations that face disparities

Promoting healthy beverage choices with an emphasis on access to fresh, potable (clean) water with a particular focus on adolescents

Discussions and breakout sessions centered on how these strategies may be applied to reduce obesity-related health disparities. DNPAO charged the panelists with designing and vetting a specific process on “how to” address obesity disparities and achieve health equity. The meeting’s opening plenary session included presentations on the social determinants of health equity and was followed by a series of three facilitated panel discussions, held over the first 2 days of the meeting.

The first session focused on policy recommendations, disparities data, data gathering, and using data. Experts provided suggestions on how DNPAO can better assist grantees in collecting and using data to support obesity prevention activities. One of the suggestions included creating a data repository that is easily accessible for states as well as translation of data that can effectively be used when speaking to policy makers. Experts also discussed how state grantees can better measure and assess nutrition, physical activity, and obesity data as they relate to groups showing the highest disparities in obesity. Examples included ensuring that measures have equivalence for non–English speaking populations, collecting data relevant to high-priority groups such as the disability community, and diversifying the mode of survey data collection (i.e., web-based, multimodal surveys, etc.).

The second session focused on lessons from the field and addressing program and infrastructure needs. Experts provided examples of how they had been successful in promoting physical activity, nutrition, and obesity reduction in disparate populations through policy, systems, and environmental interventions or approaches. Panelists also identified barriers and facilitators to addressing disparities related to physical activity, nutrition, and obesity.

The third session focused on partnerships and environmental supports, communications, and marketing. Experts identified ways that DNPAO could assist grantees connecting with partners and how to use these partners to work toward the implementation of policy, systems, and environmental strategies. Panelists also discussed ways that grantees could best use communication and marketing to promote physical activity, nutrition, and obesity reduction among disparate populations.

The final half-day of the meeting focused on discussing the development of the Health Equity Resource Toolkit. Preliminary thinking about the Toolkit was presented to the panel and the experts were given the opportunity to provide input on the development process and areas for content focus. The panelists took into account discussions and ideas presented during the first 2 days of the panel meeting and provided final recommendations on what they believed the Toolkit should include and how it should be structured in order to be most useful for state grantees. At the conclusion of the panel, transcripts were synthesized and organized into specific guidance, resources, and recommendations that formed the basis of Toolkit development.

Review of Existing Planning and Change Models

A six-step planning process was developed for the Toolkit by integrating key steps from four published planning and change models (Bryson, 1988; Centre for Health Promotion, 2001; Green & Kreuter, 2005; King, Glasgow, & Leeman-Castillo, 2010). This information was supplemented by recommendations from the expert panel. Although many effective planning processes exist, this Toolkit integrates key steps from a variety of planning and change models into a simple six-step planning process (for more information about general planning models, see page 17 of the Toolkit, http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/toolkit.html).

Case Studies

CDC project officers, based on their experience working with state program grantees, identified states used as case studies in the Toolkit. These case studies illustrate how a state program successfully implemented one of the six steps in the planning process.

METHOD

Content and Structure

The content and structure of the Toolkit includes providing information on the framework used, the goal of the Toolkit, the planning process and case studies used, and resources provided.

Social Ecological Model

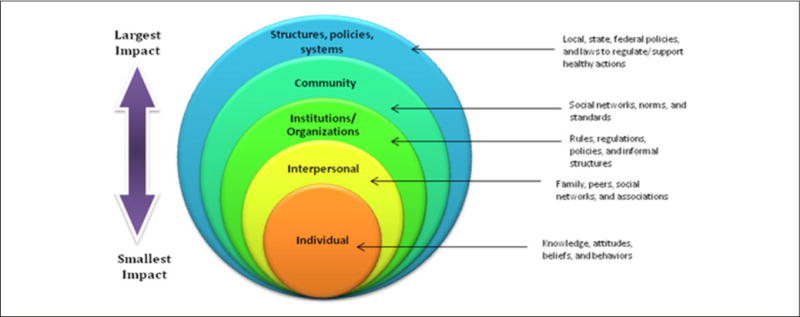

The Toolkit addresses obesity using the social ecological model (SEM; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988; Figure 1). The SEM depicts the relationship between health behaviors and individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and social subsystems (Green, Richard, & Potvin, 1996; Richard, Potvin, Kishchuck, Prlic, & Green, 1996; Sallis & Owen, 1997). It effectively links the complexities of health determinants and environmental influences on health (Green et al., 1996).

FIGURE 1. The Social Ecological Model.

NOTE: This Toolkit focuses on systems and environmental level interventions that are more likely to have a greater population impact on obesity and obesity disparities than individual-level interventions (adapted from the health impact pyramid).

Whereas interventions to prevent obesity can effectively take place at multiple levels of the model, the Toolkit emphasizes systems and environmental-level interventions. These high-level changes, particularly at the state and local levels, have the potential for a broader and more sustainable population impact than individually oriented approaches to obesity prevention (Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2009; Brownson, Haire-Joshu, & Luke, 2006). With careful planning, there is the potential to have an impact on the obesity epidemic and, in particular, to reduce the obesity-related health disparities often affecting those populations that are at highest risk.

The Toolkit is a unique resource as it is developed for state-level health departments and practitioners who work with and through communities, rather than solely addressing communities themselves. The Toolkit is not prescriptive. The process presented can either be followed in linear order or parts of the process can be referenced as needed, depending on what is most useful to the state program. It begins with an introduction of the burden of obesity in the United States and some of the disparities in the experience of that burden. The Toolkit then provides a description of a recommended conceptual framework, the SEM, and follows with sections that discuss a six-step planning process. Each planning section contains (a) a basic description of the steps of the process and suggested evidence-informed actions to help address obesity disparities, (b) practical tools for carrying out activities to help reduce obesity disparities, and (c) a “real-world” case study of a successful state-level effort to address obesity with a focus on health equity that is particularly relevant to the content in that section. Hyperlinks to additional resources are included throughout.

Toolkit Goal

The goal of the Toolkit is to enhance the capacity of state health departments and their partners to work with and through communities to implement effective responses to obesity in populations that face health disparities. The Toolkit’s primary focus is to create systems and environmental changes that will reduce obesity disparities and achieve health equity. Many of these changes include the introduction of procedures or practices that apply to large sectors that can influence complex systems in ways that can improve the health of a population. States are already conducting activities to address obesity across populations. The Toolkit provides guidance on how to supplement and complement existing efforts by presenting a six-step planning process (developed by SciMetrika, LLC) to address obesity disparities through a health equity lens. In addition, the Toolkit provides evidence-informed and real-world examples of addressing disparities by illustrating how the concepts presented can be promoted in programs to achieve health equity using three evidence-informed strategies explored during an expert panel. Though the Toolkit uses these strategies as examples, the planning and evaluation process described in the Toolkit can be applied to other evidence-informed strategies to control and prevent disparities.

Planning Process

Although many effective planning processes exist, the Toolkit presents a way to integrate key steps from a variety of planning and change models into a simple six-step planning process (Figure 2). The six steps in the process of addressing obesity disparities through a health equity lens include:

Program assessment and capacity building: Internal and external assessments of programs and policies, such as Health Equity Impact Assessments and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) Analyses, lay the groundwork for an effective obesity health equity initiative. Subsequently, identified weaknesses in capacity can be addressed using a number of tools and resources referenced in this section. Resources are also offered in this section that broaden the vision of how to address health disparities, which can be an important and fruitful perspective shift in the early stages of the planning process.

Gathering and using data to identify and monitor obesity disparities through a health equity lens: State- and community-level data can provide direction on how and where to concentrate obesity prevention efforts to achieve health equity. Quantitative data, including data collected through a Geographic Information System or data on obesity and related behaviors (e.g., Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System), can be instrumental in identifying and monitoring obesity disparities and the factors that contribute to them. Links to a range of quantitative data sources that span national- to community-level data are listed in this section. Qualitative data can also offer a unique community or practitioner point of view on barriers to obesity control and prevention and how to overcome them. This section also includes examples of qualitative data used by communities to identify barriers to healthy eating.

Developing multisector and nontraditional partnerships: Partnerships bring a number of assets to an initiative, including shared resources, increased power and strength, a greater likelihood of initiative sustainability, flexibility to adapt, and program champions. Engaging the community affected by an initiative throughout its development can especially add to its vitality and success. This section expands the notion of partnership across sectors to include government, nonprofit, private and public organizations, community groups, and/or individual community. It walks through the process of how to decide which partners to bring into an initiative and why, highlighting tools that can facilitate this decision.

Applying a health equity lens to the design and selection of strategies: In this section, a series of steps is described through which partners are brought together to discuss data, prioritize an evidence-informed systems or environmental approach, assess the health impact of the potential approach, and design an implementation and communication plan. Each step is reinforced with resources and examples of how states have followed the step successfully.

Monitoring and evaluating progress: Monitoring progress can guide program efforts and help quickly identify unintended negative consequences, and evaluation can measure the extent to which a program had the desired effect. When shared, evaluation results can contribute to the progress of the emerging field of health equity and obesity prevention and control. The evaluation section provides the basics of creating a logic model adapted for planning and evaluating environmental-level interventions; it also provides an overview of formative, process, and outcome evaluation methods to assess the success of environmental change strategies. It connects the reader with additional evaluation resources and measures, and provides examples of their application to the obesity strategies highlighted in the Toolkit.

Ensuring sustainability: Systems and environmental changes are often the most sustained approaches to improving public health. In addition to initiating a systems or environmental approach relative to health equity for obesity prevention, there are a number of ways to further ensure sustainability. This section outlines frameworks and strategies to increase sustainability, including coalition building, developing a diverse financial base, and planning from the beginning with sustainability in mind.

Continuous communication and adaption for cultural competency are included in the center of the figure to highlight the importance of communication and cultural competency throughout the entire process.

FIGURE 2. Health Equity in Obesity Planning Process.

NOTE: The Health Equity in Obesity Planning Process is a general planning process developed from multiple planning processes and models for the Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities (developed by SciMetrika, LLC.)

Case Studies

Included in each of the six planning sections are “real-world” case studies of a successful state-level effort to address obesity with a focus on health equity that is particularly relevant to the planning section’s content. The case studies illustrate how a state-level action was able to accomplish addressing obesity through a health equity lens.

Resources

Resources, tools, and examples are included within each section of the Toolkit. In addition to this guidance, the Toolkit appendices provide additional extensive resources relevant to obesity prevention to further guide the reader. Appendices A to C contain resources relevant to obesity prevention organized by the three strategies mentioned above. Appendix D provides a comprehensive, centralized list of the tools, examples, and other resources provided throughout the planning and evaluation process laid out in the Toolkit, organized by the section.

NEXT STEPS

Web-Based Resource

DNPAO and SciMetrika, LLC, recently developed a complementary web-based resource to guide practitioners in their application of the Toolkit to new and existing programs for reducing health disparities in obesity (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/index.html).

The web-based guide is a supplementary resource intended to deepen practitioners’ understanding, and facilitate their use of the Toolkit contents. A vital function of the website is to provide direct access to the electronic version of the complete Toolkit. Practitioners are encouraged to download the Toolkit and familiarize themselves with its contents before beginning implementation. Additionally, practitioners are referred to individual sections of the Toolkit throughout their navigation of the website.

The specific objectives of this complementary web-based resource are to the following:

Provide an overview of the Toolkit content

Provide supplementary information, examples, and exercises to reinforce or expound on Toolkit content

Guide users in the most effective application of the Toolkit’s sections

Provide access to additional resources and tools to complement those found in the Toolkit

CONCLUSION

CDC promotes evidence-based and practice-informed strategies to address nutrition and physical activity environments and behaviors to reverse the obesity epidemic. The Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities assists public health practitioners with a systematic approach to program planning using a health equity lens. As described in the Institute of Medicine’s (2012) Workshop Summary titled “How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities?” there are a number of themes practitioners should focus on, including a need for continued efforts to address health disparities; the recognition of the persistence of health disparities, especially given the state of the economy; and the importance of place, particularly the role of environmental factors, in influencing health outcomes. The Toolkit can be a valuable resource to help address these ongoing concerns.

As practitioners use the Toolkit and engage in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of approaches to reduce obesity disparities, they should evaluate and report their findings, challenges, and successes. This will help document whether the six-step planning framework to address obesity disparities presented in the Toolkit is effective and helpful, and how it may be modified to fit individual program needs. Other information that will be of benefit to the field are reports of measurement approaches and methods to bring interventions to scale. This information can help increase the knowledge base and guide others on how best to implement strategies to achieve health equity.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Contract #200-2008-27889. We would like to thank and acknowledge the following state representatives who provided valuable feedback during development of the Toolkit: Allison Faricy, Minnesota Department of Health; Michelle Futrell and Jenni Albright, North Carolina Division of Public Health; Dennis Haney, Iowans Fit for Life; Nestor Martinez, California Project LEAN, California Department of Public Health; and Sia Matturi, Michigan Department of Community Health. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Berkeley Media Studies Group. What surrounds us shapes us: Making the case for environmental change (Framing Brief written for the Strategic Alliance’s Rapid Response Media Network and The California Endowment’s Healthy Eating, Active Communities program) 2009 Retrieved from http://www.bmsg.org/pdfs/Talking_Upstream.pdf.

- Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Lersen P, Kiefe CO, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: Longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: The CARDIA study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171:1162–1170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: A review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:341–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson JM. A strategic planning process of public and non-profit organizations. Long Range Planning. 1988;21:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Promotion, Health Communication Unit. Introduction to health promotion program planning. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto; 2001. Retrieved from http://www.thcu.ca/infoandresources/publications/planning.wkbk.content.apr01.format.oct06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disseminating program achievements and evaluation findings to garner support (Evaluation Brief) 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief9.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: State-specific obesity prevalence among adults, United States 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:951–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health equity resource toolkit for state practitioners addressing obesity disparities. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding JE, Simon PA. Food deserts or food swamps. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171:1171–1172. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach. 4. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10:270–281. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Drewnowski A, Kumanyika SK, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6:A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Progress since 2000: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. How far have we come in reducing health disparities? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DF, Glasgow RE, Leeman-Castillo B. Reaming RE-AIM: Using the model to plan, implement and evaluate the effects of environmental change approaches to enhancing population health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2076–2084. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecologic perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll M. Prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents: United States, trends 1963–1965 through 2007–2008 (NCHS Health E-Stat) 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_child_07_08.htm.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuck N, Prlic H, Green L. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10:318–328. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis F, Owen N. Ecological models. In: Glanz K, Lewish L, Rimer RK, editors. Health behavior and health education theory research and practice. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]